Abstract

GLP-1 (9-36)amide is the cleavage product of GLP-1(7-36) amide formed by the action of diaminopeptidyl peptidase-4 (Dpp4) and is the major circulating form in plasma. Whereas GLP-1(7-36)amide stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion, GLP-1(9-36)amide has only weak partial insulinotropic agonist activities on the GLP-1 receptor, but suppresses hepatic glucose production, exerts antioxidant cardioprotective actions, and reduces oxidative stress in vasculature tissues. These insulin-like activities suggest a role for GLP-1 (9-36)amide in the modulation of mitochondrial functions by mechanisms independent of the GLP-1 receptor. Here we discuss the current literature suggesting that GLP-1(9-36)amide is an active peptide with important insulin-like actions. These findings have implications in nutrient assimilation, energy homeostasis, obesity, and the use of Dpp4 inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes.

Multiple Glucagon-like peptides modulate glucose metabolism

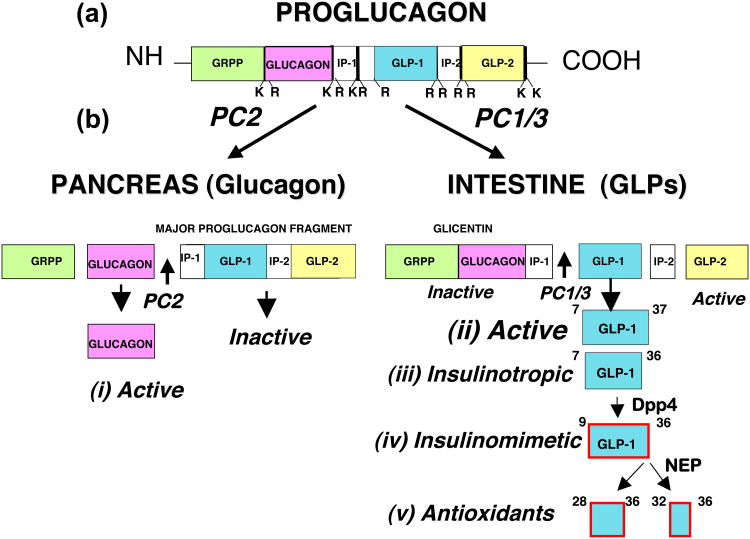

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a glucoincretin hormone produced in the entero-endocrine cells of the intestines and secreted in response to feeding. It is one of several peptide hormones cleaved from the precursor protein, proglucagon. Other cleavage products include glucagon and the glucagon-like peptides 1 and 2 (Figure 1). Glucagon is the major hormone produced by the alpha cells of the pancreatic islets during fasting conditions, whereas the GLPs are produced by the intestine in response to feeding [1]. GLP-2 promotes growth of the intestinal mucosa [2], while glucagon promotes hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis) during the post absorptive period [3]. GLP-1 is best known as a potent insulinotropic hormone that stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion [1,4]. Both GLP-1 agonists and inhibitors of the enzyme Dpp4 that inactivates the insulinotropic actions of GLP-1 are approved and in use for the treatment of type 2 diabetes [4]. It is now becoming understood, however, that GLP-1 also has insulin-like (insulinomimetic) actions independent of its insulinotropic actions, which is the focus of this article. The reader is also referred to an informative recent review of the extra-pancreatic actions of GLP-1 [5].

Figure 1.

Proglucagon is a protein precursor of glucagon and glucagon-like peptides (GLPs). (a) The multifunctional proglucagon is cleaved by (b) site-selective proteases (PC2, PC1/3) in the pancreas to liberate (i) glucagon as the active peptide and (ii) GLP-1 and GLP-1 in the intestine.. The prohormone convertases PC2 and PC1/3 selectively cleave proglucagon to produce glucagon and GLPs, respectively. (iii) The insulinotropic GLP-1 peptides are GLP-1(7-36)amide and a glycine-extended form GLP-1(7-37). They are released from the intestine in response to feeding and stimulate glucose-dependent insulin secretion. These insulinotropic GLP-1s are rapidly converted after their secretion to (iv) insulinomimetic hormones GLP-1(9-36)amide and GLP-1(9-37) by removal of the N-terminal two amino acids by the diaminopeptidyl peptidase-4 (Dpp4). These may be further cleaved by neutral endopeptidases (NEP) to produce (v) small C-terminal peptides; a nonapeptide and pentapeptide, GLP-1(28-36)amide and GLP-1(32-36)amide, and the corresponding decapeptide and hexapeptide GLP-1(28-37) and GLP-1(32-37). It is proposed that these small peptides may target mitochondria and modulate oxidative phosphorylation, glucose and fatty acid metabolism, and energy expenditure resulting in an attenuation of oxidative stress (ROS formation) and the promotion of cell survival.

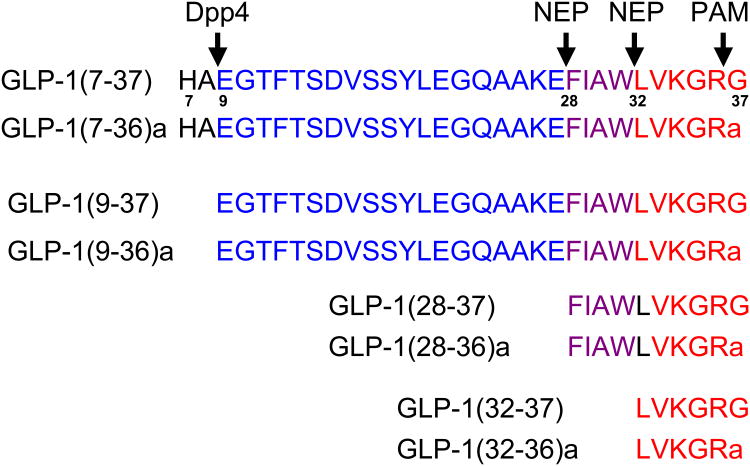

The GLP-1 hormones consist of a complex family of peptides of 28 to 37 amino acids formed by multiple post-translational enzymatically-mediated cleavages by diaminopeptidyl peptidases, endopeptidases, and C-terminal amidation by peptide amidating monooxygenases. (Figure 2). Much of the current understanding in the field considers that these GLP-1 cleavages represent degradation pathways for its inactivation and disposal [6,7]. Alternatively, the temporal, successive enzymatic cleavages of GLP-1 may importantly modify its biological activities, such as changing its function from an insulin-releasing hormone to an insulinomimetic hormone that acts on insulin-sensitive target tissues to facilitate nutrient assimilation and metabolism.

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequences of Glucagon-like peptides-1 and sub-peptides generated by selective modifications by specific proteases. The parent insulinotropic peptide is cleaved out from the proglucagon precursor by the actions of prohormone convertase type 1/3. The carboxylterminus of GLP-1 is modified at the time of synthesis by the actions of peptide amidating monooxygenase (PAM) which removes the carboxyl terminal glycine (G) and amidates the penultimate arginine (R). Within minutes after their secretion into the circulation, the GLP-1(7-36)amide and GLP-1(7-37) are modified by removal of the amino-terminal amino acids, histidine (H) and alanine (A) (black font) by the diaminopeptidyl peptidase-4 (Dpp4). Cleavage by Dpp4 yields the insulinomimetic peptides, GLP-1(9-36)amide and GLP-1(9-37). It is proposed that additional cleavages within the carboxy-terminal domains of the insulinotropic peptides by endopeptidases (NEP), such as the selective cleavages by neutral endopeptidase 24.11, generates small penta- (red font) to deca-peptides (purple + red font) that target mitochondria and thereby modulate oxidative phosphorylation, energy expenditure, and apoptosis.

Here we propose a Dual Receptor Hypothesis of GLP-1 actions, whereby the initial GLP-1 isopeptide acts on cell surface receptors on pancreatic β-cells to augment glucose-dependent insulin secretion. The initial insulinotropic peptide is rapidly modified by removal of two amino acids, allowing access of the modified GLP-1 to a translocation receptor that transports GLP-1 across the plasma membrane into the cell where additional cleavages by endopeptidases release small peptides of 5 to 9 amino acids from the C-terminus of GLP-1. These small peptides target the mitochondria to modulate oxidative phosphorylation involving fatty acid and glucose metabolism, energy expenditure, and apoptosis. By this mechanism, GLP-1 has a distinct dual role in nutrient metabolism -- first, to stimulate pancreatic insulin secretion and second, to enhance nutrient uptake and metabolism by peripheral insulin-sensitive tissues.

Insulinotropic actions of GLP-1

The insulinotropic actions of GLP-1 were discovered two decades ago and are thoroughly described in numerous review articles [1,8]. In brief, the amino-terminally extended insulinotropic hormones, GLP-1 (7-37) and GLP-1 (7-36)amide, rapidly stimulate glucose-dependent insulin secretion within one minute after their systemic administration into animals or humans, working via G-protein coupled receptors on pancreatic insulin-producing β-cells. GLP-1 receptors (GLP-1Rs) are present in several organs including the pancreatic islets, heart, lungs, skin (hair follicle), stomach, hypothalamus and brain stem. In addition to stimulating insulin secretion, GLP-1R activation enhances growth and survival of β-cells, inhibits gastric emptying and glucagon secretion, is cardio-protective, and promotes satiety [8]. The GLP-1R is coupled to Gs and activates signal transduction pathways that include cAMP/PKA, PI3K/Akt, and MEK/ERK.

Several GLP-1R agonist-based therapies are currently approved and in use for the treatment of type 2 diabetes [4,9]. The activation of cAMP in β-cells by GLP-1 appears to act synergistically with glucose metabolism in increasing insulin secretion and renders β-cells competent to respond to glucose [10]. Glucose is required for GLP-1-mediated stimulation of insulin secretion, the so-called glucose competence concept [10].

Selective enzymatic cleavages of GLP-1 into peptides with novel bioactivities

Of considerable importance is the finding that the insulinotropic GLP-1s have a very short existence in the circulation. They are rapidly (t1/2 = 1-2 min) cleaved after their secretion into the circulation by the diaminopeptidyl peptidase-4 (Dpp4), resulting in the production of the amino-terminally shortened peptides, GLP-1(9-37) and GLP-1(9-36)amide, which have weak, if any, insulin-releasing activities [11]. GLP-1(9-37) and GLP-1(9-36)amide are the major circulating forms of GLP-1, comprising about 80-90% of the total circulating GLP-1s [12], with a t1/2 of 8-10 minutes. In studies of GLP-1 secretion from the pig intestine, approximately 60% of GLP-1 released exists in the form of GLP-1(9-36)amide due to rapid cleavage of GLP-1(7-36)amide by Dpp4 located on vascular endothelial cells at the site of secretion from L-cells [13]. Since levels of total GLP-1 in the circulation are only in the range of 100 pM, the active insulinotropic hormones GLP-1(7-37) and GLP-1(7-36)amide are remarkably low (10 pM), indicative of a relatively high affinity of the GLP-1 receptor for interactions with the insulinotropic GLP-1s. That GLP-1(9-37) and GLP-1(9-36)amide peptides make up the majority of circulating GLP-1 hormone and are relatively stable suggests their biological activities apart from stimulating insulin secretion.

The neutral endopeptidase NEP 24.11, known as neprilysin, CD10, and CALA antigen [14], is another endoprotease, distinct from Dpp4, implicated in GLP-1 degradation. NEP 24.11 cleaves GLP-1 at several internal sites amino-proximal to bulky hydrophobic amino acids such as phenylalanine and leucine [15]. NEP 24.11 is predominantly a membrane-associated enzyme that is expressed in the central nervous system, at high levels in hepatocytes on the surfaces of bile caniculi, and in other organs [16]. Therefore, an intracellular form of NEP 24.11, or an endopeptidase with similar specificity, might be responsible for internal cleavages of GLP-1. Similar to Dpp4, NEP 24.11 is currently considered to function as a degrading enzyme for the destruction and disposal of GLP-1 [6].

Insulin-like and cytoprotective actions of GLP-1(7-36)amide and GLP-1(7-37)

Although it is difficult to detect insulin-like effects of the insulinotropic GLPs, GLP-1(7-37) and GLP-1(7-36)amide, because of their insulin-releasing activities, several studies suggested that GLP-1 has insulin-like actions on peripheral glucose uptake and metabolism independent of its effects on insulin secretion and changes in plasma insulin levels. Egan and co-workers [17] showed that hepatic glucose uptake (Rd) was greater in response to GLP-1(7-37)-induced insulin release compared to insulin given by infusion in obese insulin-resistant human subjects. Notably, a similar study in lean insulin sensitive subjects showed no effects of GLP-1(7-37) on Rd [18] compared to insulin infusion. Subsequent studies in ob/ob obese insulin-resistant mice using GLP-1(7-37) or the long-acting GLP-1 agonist exendin-4 revealed an inhibition of hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis) [19] and a reduction in hepatic steatosis [20], respectively. A single injection of an adenovirus-exendin-4 expression vector to diet-induced obese mice decreased weight gain without detectable changes in food intake, increased energy expenditure, and enhanced insulin action manifested by reducing hepatic fat and enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis and fatty acid synthesis [21]. These findings of Sampson and co-workers are similar to those reported by Ding et al showing that the administration of exendin-4 to ob/ob mice reduced steatosis and increased the expression of hepatic enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation [20].

In isolated rat hepatocytes ex vivo, GLP-1(7-36)amide activates the activity of glycogen synthase-a, proposed to be via PI3kinase and Akt signaling since the activation by GLP-1 was inhibited by Wortmannin [22] This study suggests GLP-1 actions on liver by receptor mechanisms that are distinct from those that mediate the insulinotropic actions on pancreatic β-cells, but cannot definitively exclude the possibility that these peripheral extra-pancreatic actions of GLP-1 are attributable to small changes in plasma insulin levels stimulated by insulinotropic GLP-1s.

Evidence for direct GLP-1(9-36)amide actions on the heart

One of the first observations of direct effects of GLP-1(9-36)amide on the heart was made by Nikolaidis and co-workers [23] who infused GLP-1(9-36)amide into dogs with severe heart failure due to experimentally-induced rapid pacing resulting in dilated cardiomyopathy. These dogs are severely stressed and hyperinsulimemic. The direct infusion of GLP-1(9-36)amide rapidly reversed the heart failure, improved end diastolic pressure, and markedly stimulated myocardial glucose uptake without changing plasma insulin levels. These findings are indicative of enhanced glycolysis (glucose oxidation) [23]. Cardio-protective effects of GLP-1(9-36)amide were also demonstrated in mice with experimentally induced ischemic injury and post ischemic reperfusion injury [24]. GLP-1(9-36)amide perfused in isolated mouse hearts with ischemic myocardial damage improved cardiac function, increased vasodilatation and coronary blood flow, and reduced the extent of ischemia-induced injury to the myocardium. These beneficial effects of GLP-1(9-36)amide in the heart were accompanied by demonstrable increases of myocardial cGMP, inducible nitric oxide synthase activity, and nitric oxide generation, consistent with an antioxidant action and reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) [24]. Remarkably, many of the improvements in the murine myocardium produced by GLP-1(9-36)amide were seen in conditions of complete receptor blockade, e.g. in the hearts of GLP-1R null mice, and in mice co-infused with GLP-1(7-36)amide and the GLP-1R antagonist exendin(9-39) [24,25]. Similarly, Sonne et al [26] tested the effects of both the GLP-1 agonist, exendin-4 and GLP-1(9-36)amide on post-ischemic reperfusion injury in the isolated rat heart and found that both peptides augmented left ventricular performance and were only partially inhibited by the GLP-1R antagonist exendin(9-39).

These findings in ischemic hearts in conditions of increased oxidative stress lead to the conclusion that GLP-1 exerts important biologic actions on the ischemic heart independent of those mediated by GLP-1R, suggesting the existence of novel mechanisms of actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide in this tissue. These antioxidant cardiac actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide are reminiscent of those of SS (Szeto-Schiller) peptides derived by modifications of carboxylterminal sequences of cholecystokinin with opioid agonist activities [27]. The SS peptides consist of a family of tetrapeptides of the general structure H-B-H-B, where H is a bulky hydrophobic amino acid and B is a basic amino acid, either arginine or lysine. SS peptides readily enter cells and target mitochondria to inhibit ROS formation and apoptosis, which can protect against ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial stunning in guinea pigs [28] and rats [29]. It is tempting to speculate that if GLP-1 can enter target cells by endocytosis or other mechanisms, the C-terminal peptides LVKGR and LVKGRG, potentially derived by cleavages by an intracellular form of the neutral endopeptidase NEP24.11 [15], or an enzyme of similar specificity, may target mitochondria and serve as antioxidant peptides.

Evidence for direct actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide on vasculature

As has been found in the heart, GLP-1(9-36)amide also exerts potent antioxidant actions on the vasculature. Studies by Green and co-workers [30] demonstrate that insulinotropically-inactive peptides GLP-1(9-36)amide and exendin(9-39), a GLP-1R antagonist as well as agonists, GLP-1(7-38)amide and exendin-4 all have significant vaso-relaxant properties on the isolated rat aorta. These relaxant actions of the GLP-1s appear to be mediated, at least in part, via cAMP and opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels [30]. Remarkably, in studies carried out in rat femoral arterial rings (conduit arteries) ex vivo, both GLP-1(7-36)amide and GLP-1(9-36)amide produced a marked vasorelaxation response whereas exendin-4 exerted no observable vasorelaxation activity [31]. The reason for these observed differences between the GLP-1 peptides and the long-acting GLP-1 agonist exendin-4 in promoting vasorelaxation remains unexplained [30]. Both exendin-4 and GLP-1(7-36)amide are full agonists and GLP-1(9-36)amide is a weak partial agonist on the GLP-1 receptor [32]. One speculation derived from these studies is that GLP-1(9-36)amide is mediating vasorelaxation by a GLP-1 receptor-independent mechanism, and that the vasorelaxation activities observed with GLP-1(7-36)amide is a consequence of its cleavage to GLP-1(9-36)amide by ambient Dpp4 activity present in the arterial ring preparations. Exendin-4 is resistant to cleavage by Dpp4, a major property that enhances its insulinotropic actions. Furthermore, these actions of GLP-1 peptides on rat conduit arteries do not require insulinotropic activity because GLP-1(9-36)amide is devoid of insulinotropic activities and exendin-4 is a potent insulinotropic peptide [30].

Collectively, these studies in vasculature tissues clearly demonstrate actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide on vascular cell metabolism independent of the GLP-1 receptor, suggesting that novel GLP-1R-independent mechanisms mediate these actions..

Evidence for direct GLP-1(9-36)amide actions on liver

As described earlier, both GLP-1(7-37) and GLP-1(7-36)amide suppress hepatic glucose production (HGP) in obese, insulin-resistant mice and humans. However, that these actions are attributable to GLP-1(9-36)amide are assumed, based on the known actions of Dpp4 to rapidly modify GLP-1(7-36)amide to the GLP-1(9-36)amide metabolite. Recently, studies showed that infusion of GLP-1(9-36)amide in obese, insulin-resistant human subjects under fasting and glucose clamp conditions dramatically lowers hepatic glucose production by up to 50%, beginning 15-20 minutes after the start of the infusions [33]. This remarkable inhibition of hepatic glucose production was observed in the obese, insulin-resistant and not in the lean, insulin-sensitive subjects [33]. It is worth noting that an earlier study of the infusion of GLP-1(9-36)amide into healthy nonobese, presumably insulin-sensitive subjects also produced no effects on insulin release or on glucose metabolism (34). The delay of 15-20 minutes before the onset of the suppression of HGP by GLP-1(9-36)amide in obese, insulin-resistant subjects in the post-absorptive state strongly suggests that GLP-1(9-36)amide exerts actions on intermediary metabolism. It is well known that plasma glucose levels are maintained by hepatic gluconeogenesis in the post-absorptive state after glycogen stores are depleted. Since conditions of fasting and insulin resistance limit the availability of glucose for oxidation as an energy source, energy production occurs predominantly from fatty acid oxidation. The glucose metabolism and fatty acid metabolism cycles are known to be reciprocally coupled [35]. Thus, a reduction of gluconeogensis induced by GLP-1(9-36)amide is likely to be a consequence of inhibition of fatty acid oxidation. The major factors that fuel gluconeogenesis in the liver are AcetylCoA derived from fatty acid oxidation and glycerol derived-from lipolysis. Therefore, it seems reasonable to speculate that a target action of GLP-1(9-36)amide on the suppression of gluconeogensis may be at the level of the inhibition of fatty acid oxidation, beta-oxidation that takes place in the matrix of mitochondria.

The suppression of hepatic glucose production by infusion of GLP-1(9-36)amide may not be due entirely to a direct effect of the peptide on hepatocytes, but rather to effects mediated by actions of the peptide on the autonomic nervous system. Recent evidence suggests that GLP-1 receptors exist on vagal afferent nerve terminals in the portal vein. Studies in rats [36] and dogs [37] indicate that GLP-1 infusions into the portal vein enhance hepatic glucose uptake and production; these effects are reversed by the administration of exendin9-39, a specific GLP-1 receptor antagonist. Moreover, the direct administration of GLP-1 centrally into the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus in rats augmented glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and reduced hepatic glucose production, and administration of the exendin9-39 antagonist caused relative hyperglycemia [38]. These studies, however, do not address actions of the insulinomimetic GLP-1(9-36)amide, which is only a weak partial agonist of the GLP-1 receptor [32] and unlikely to act on the GLP-1 receptors in the portal vein and hypothalamus. If the GLP-1(9-36)amide used in the studies reported by Elahi et al [33] reduced hepatic glucose output via a central effect, it likely does not involve GLP-1 receptors. Indeed, there is conflicting evidence that the intraportal GLP-1 actions on glucose uptake and metabolism through the hepatic vagal nerve are GLP-1 receptor-mediated. Intraportal injections of the GLP-1 agonist exendin-4 was without effect and the GLP-1 receptor antagonist exendin(9-39) failed to modify GLP-1-stimulated afferent vagal nerve activity in rats [39]. Moreover, GLP-1 administered either via the hepatic artery or portal vein in dogs increased hepatic glucose uptake equivalently suggesting that the increased hepatic glucose uptake does not involve GLP-1 receptors located in the portal vein [40]. Based on the sum of the evidence, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that at least some of the actions of GLP-1 on glucose uptake and metabolism in the liver occurs via mechanisms that are independent of the GLP-1 receptor. An alternative, as yet unidentified receptor-independent mechanism might be involved in mediating the actions of GLP-1 on hepatic glucose metabolism.

Enigma of GLP-1 receptor expression in hepatocytes

Whether or not the GLP-1R is expressed in hepatocytes remains an enigma, with some studies reporting GLP-1R expression in rat [20,41] and human [42,43] hepatocytes, while others report no GLP-1R expression in rat [44,45], mouse [46], or human [43,47] hepatocytes. Of interest, Flock and co-workers [46] not only did not detect GLP-1R mRNA transcripts by RTPCR analysis of RNA isolated from cultured murine hepatocytes, but also were unable to detect any stimulation of cyclic AMP formation after incubation of murine hepatocytes with GLP-1 or exendin-4. Notably, both glucagon and forskolin significantly increased levels of hepatocyte cyclic AMP in the same experiments [46].

A recent paper by Aviv and co-workers [43] describes the activation of cAMP formation, CREB, PKB, and ERK1/2 with a burst-decay kinetics within 5-15 minutes after the addition of exendin-4 to isolated human hepatocytes. These remarkable findings of the activation of cAMP formation by exendin-4 are reminiscent of those reported by Ding et al [20] in isolated rat hepatocytes. Notably, however, Aviv et al failed to detect GLP-1 receptor expression in human hepatocytes prior to their trans-differentiation into pancreatic β-cells [43]. Such an observed burst-decay response of cells to a peptide hormone is a representative signature response of a Gs-coupled receptor and strongly suggests that exendin-4 actions on hepatocytes are mediated by a G-protein coupled receptor other than GLP-1R. Candidate alternative receptors may be members of the family of structurally-related receptors for the glucagon super-family of peptide hormones. It is tempting to speculate that such a receptor may even be the glucagon receptor. Since the glucagon receptor is structurally similar to the GLP-1 receptor and is abundantly expressed in hepatocytes, these findings raise the intriguing possibility that exendin-4, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, activates the glucagon receptor in liver. This theoretical activation of glucagon receptors by exendin-4 may in some way depend on the metabolic state of the hepatocytes. A further speculation is that the amino-terminally truncated GLP-1 peptide, GLP-1(9-36)amide, may act as an antagonist, or even as an inverse agonist, of the glucagon receptor in the liver. If so, this circumstance could offer an explanation for the suppression of hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis) in response to infusions of GLP-1(9-36)amide in human subjects reported by Elahi and co-workers [33]. Of note are the findings that the actions of GLP-1(9-36) to suppress hepatic glucose production in human subjects were manifested in obese, insulin-resistant, but not lean, insulin-sensitive subjects [33] suggesting that some unknown alteration of the hepatocytes in the obese, e.g., steatosis, may be a prerequisite for the inhibitory actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide on the glucagon receptor and the consequent inhibition of gluconeogenesis.

In summary, there appears to be a clear effect of GLP-1 on peripheral glucose metabolism independent of its insulinotropic actions. Some of these actions on liver appear to be mediated through the vagal nerve terminals in the portal vein, centrally in the hypothalamus or directly in liver. Notably, actions of GLP-1 on vagal nerve terminals in the portal vein seem to be mediated by GLP-1 receptor-independent mechanisms. It is important to note that all of these mechanisms of GLP-1 actions on glucose metabolism, direct on hepatocytes, on vagal nerve terminal in the portal vein, and central actions in the hypothalamus, are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and could be shared by GLP-1 (9-36)amide as well.

Mechanisms of insulin-like actions of GLP-1 on liver, heart and vasculature: A hypothetical model

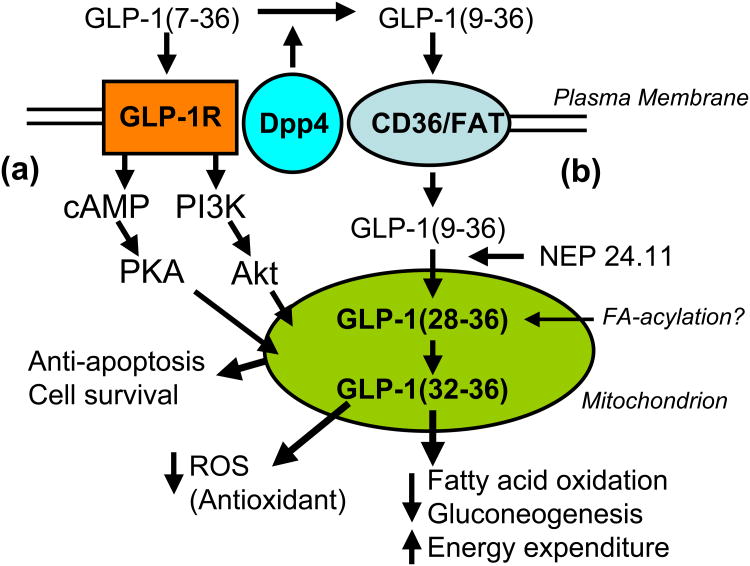

Most evidence regarding the insulinomimetic actions of GLP-1 on the heart, liver, and vasculature indicates that both GLP-1R dependent and independent mechanisms are involved. Moreover, it seems that insulin-like actions of GLP-1 on liver, heart, and vasculature could be mediated at the level of mitochondrial function, e.g., regulating oxidative phosphorylation, ROS formation, gluconeogenesis, and fatty acid oxidation. Mitochondria are complex intracellular organelles with their own genome whose primary roles are to regulate energy production and utilization and modulate programmed cell death (apoptosis) [48]. Two hypothetical mechanisms are proposed based on the cumulative evidence supporting insulin-like actions of GLP-1 on insulin-sensitive tissues independent of its insulinotropic actions (Figure 3). One mechanism is mediated by GLP-1(7-36)amide binding to GLP-1R, activating downstream signaling pathways such as cAMP/PKA and PI3K/Akt. Both PKA and Akt target mitochondria and regulate apoptosis [48]. Activated PKA targets the cytoplasmic surface of mitochondria resulting in phospho-inhibition of the proapoptotic protein BAD, enhancing cell survival [49]. Akt enhances cell survival by targeting mitochondrial membranes, and to some extent the matrix, where it inhibits GSK3, an important enzyme that enhances apoptosis by inhibiting mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase, an enzyme important for glucose oxidation [50]. A caveat to the GLP-1R activation hypothesis is that the expression of the GLP-1R in hepatocytes remains controversial, since these hypothetical actions of GLP-1 on the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) require that the GLP-1R be expressed in hepatocytes. In the absence of hepatic GLP-1R expression, one might speculate that some other G-protein receptor expressed in hepatocytes is activated by GLP-1 agonists, such as the glucagon receptor, or another receptor in the glucagon super-family of peptides related to the GLP-1R.

Figure 3.

Model depicting two hypothetical cell signaling pathways by which GLP-1 exerts insulinomimetic actions on insulin-sensitive target tissues. (a) In one mechanism, GLP-1(7-36)amide acts on its GPCR receptor, GLP-1R, to activate cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)-dependent Akt, the pro-survival kinase. Both PKA and Akt are known to target to mitochondria and modulate cytochrome and caspase-dependent apopotosis. In the absence of the expression of the GLP-1 receptor, it is hypothesized that some other G-protein-coupled receptor related to the GLP-1R, such as the glucagon receptor, may convey signaling in response to GLP-1 agonists. (b) In the absence of the GLP-1R, e.g. in the liver, GLP-1(9-36) binds to a novel translocator receptor, such as the pattern-reading scavenger receptor CD36/FAT, that transports the peptide into the cell where it is cleaved internally by selective endopeptidases, e.g. the neutral endopeptidase NEP 24.11, to liberate a small nonapeptide GLP-1(28-36)amide and a pentapeptide GLP-1(32-36)amide that target to mitochondria. The epsilon amino group on Lysine-34 may be fatty-acylated by the fatty-acylCoA ligase. These small peptides are proposed to contain consensus mitochondrial targeting sequences, LVKGRamde or LVKGRGR, and to have antioxidant actions by suppression of fatty acid oxidation and gluconeogenesis in the liver. Transport of these peptides into the matrix of the mitochondria may be facilitated by fatty acylation of the epsilon amino group on the lysine-34 by fatty-acylCoA ligase/synthase.

The second mechanism proposed involves the binding of GLP-1(9-36) to a novel receptor such as, for a theoretical example, CD36/FAT, a pattern-reading receptor that binds and transports peptides including oxidized LDLs into cells [51-53] (Figure 3). In this mechanism, GLP-1(9-36)amide is transported into the cell where it is hypothetically cleaved internally in the C-terminal region by an intracellular form of an endopeptidase, such as neutral endopeptidase 24.11 (NEP 24.11), or enzyme with similar specificity. NEP 24.11 is also known as neprilysin, CALLA, CD10 [15]. Cleavage of GLP-1 by NEP 24.11 often occurs between amino acids Glutamate-27 and Phenylalanine-28, yielding the nona-peptide FIAWLVKGRamide [GLP-1(28-36)] and the pentapeptide LVKGRamide [GLP-1(32-36)] [15]. The sequence LVKGRamide, or LVKGRG in the example of cleavage of the glycine-extended GLP-1(9-37), is highly reminiscent of several known mitochondrial targeting motifs. These motifs include RXXRRLRG determined by random screening [54]; the mitochondrial targeting sequence, LKTRV of the protein PB1-F2, produced by the Influenza B virus upon infecting cells where it inhibits fatty acid oxidation and apoptosis [55]; the opioid agonist/antioxidant tetra-peptide, YRFR [27]; and the internal latent mitochondrial targeting sequence in NPY, KGLK, that targets internally translated, truncated NPY protein into mitochondria rather than into the ER and subsequent secretory pathway [56]. A second theoretical modification of the C-terminal nona- and pentapeptides derived from GLP-1(9-36)amide is that of fatty acylation of the epsilon amino group of Lysine-34 by the mitochondrial enzyme Fatty-acylCoA ligase/synthase that acylates lysines in histones [57]. Palmitoylation of peptides controls Golgi versus mitochondrial subcellular targeting [58].

In this hypothetical model, these small C-terminally peptides derived by directed proteolytic actions of NEP 24.11 may be transported across the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes into the matrix where the tri-functional protein and associated fatty-acylCoA dehydrogenases cleave fatty acids into the two carbon acetate fragments in the form of Acetyl-CoA (beta-oxidation). Perhaps the presence of a peptide at the site of beta-oxidation in the mitochondria would be inhibitory, since the enzymatic machinery is designed to cleave alkane bonds in fatty acids and not peptide bonds.

Based on these proposed mechanisms, the insulin-like actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide operate independently of the insulin receptor kinase signaling network. In the liver, GLP-1(9-36)amide and/or the smaller peptides GLP-1(28-36)amide and GLP-1(32-36)amide inhibit hepatic fatty acid oxidation and thereby inhibit gluconeogenesis. Uncontrolled fatty acid oxidation and corresponding gluconeogenesis in the liver promote oxidative stress, a condition believed to contribute to steatohepatitis and eventually to the development of hepatic cirrhosis [59,60]. The attenuation of fatty acid oxidation rates in the liver would benefit obese patients with the metabolic syndrome consisting of insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, high rates of uncontrolled fatty acid oxidation and lipid turnover, and accompanying elevated hepatic glucose production. In the heart and vasculature, GLP-1(9-36)amide inhibits mitochondrial ROS formation and thereby acts as an antioxidant to promote the survival and functions of myocardium and vascular endothelium. Therefore, GLP-1(9-36)amide, and C-terminal peptides derived there from, attenuate oxidative stress and may have beneficial effects on the prevention or amelioration of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy [61].

Summary

GLP-1 is a multi-functional hormone secreted from the intestine into the circulation in response to feeding, initially as a potent insulinotropic hormone that stimulates glucose-dependent insulin secretion from the pancreas and then as an insulinomimetic hormone that helps insulin in the stimulation of nutrient uptake and utilization by peripheral organs. The insulinotropic hormones GLP-1(7-36)amide and GLP-1(7-37) are rapidly modified by enzymatic cleavage to form the insulinomimetic hormones GLP-1(9-36)amide and GLP-1(7-37) with insulin-like actions on insulin-sensitive tissues. In this manner, GLP-1 first helps deliver insulin from the pancreas into the circulation and then helps insulin in the assimilation and utilization of nutrients by peripheral organs such as the liver, heart, and vasculature. The insulinotropic actions of GLP-1(7-36)amide and GLP-1(7-37) on the β-cells of the endocrine pancreas are mediated by a G-protein coupled receptor (GLP-1R) that activates cAMP-dependent PKA and PI3 kinase-dependent Akt signal transduction pathways. However, the insulin-like actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide and GLP-1(9-37) appear to occur by way of GLP-1R-independent mechanisms suggesting the existence of a novel pathway for the actions of insulinomimetic GLP-1s. That GLP-1 modulates ROS formation in heart and vasculature suggests that its actions are manifested at the level of mitochondrial functions involving oxidative phosphorylation such as fatty acid oxidation, glycolysis, and energy formation and expenditure. The discovery of insulin-like actions of GLP-1 raises interesting possibilities for the development of novel GLP-1-based therapies for treating obesity and accompanying manifestations of the metabolic syndrome, including insulin resistance, excessive oxidative stress, hepatic steatosis, accelerated cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

Future Directions

The evidence supporting direct actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide on heart and vasculature appear quite convincing. Studies have been carried out in isolated perfused heart and vascular tissues ex vivo. Such experimental models exclude the participation of centrally-mediated pathways of hormone action. Furthermore, the studies suggest that the actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide are conveyed by GLP-1 receptor-independent mechanisms and involve the modulation of mitochondrial functions such as oxidative phosphorylation. However, additional studies are needed both in vitro myocardial cell and vascular endothelium systems to explore the cellular biochemistry and pathways by which GLP-1(9-36)amide exerts anti-oxidant actions and modulates oxidative phophorylation. Studies of GLP-1(9-36)amide actions in isolated mitochondria would be most informative. The information currently available on potential actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide on liver are somewhat limited and as yet undefined. The demonstration of suppression of hepatic glucose production by infusion of GLP-1(9-36)amide in obese, insulin-resistant human subjects indicates that the peptide has biological activities in the liver, and is not a circulating inactive degradation product of GLP-1 metabolism. However, these in vivo studies leave open the question of whether the actions of GLP-1(9-36) on the liver are direct actions on receptors in hepatocytes, whether they are centrally mediated via hypothalamic receptors, or neurally mediated by receptors on vagal afferent nerve fibers in the portal vein. It is possible that all of the aforementioned mechanisms are at play. Future studies of isolated hepatocyte systems are needed to address the question of whether GLP-1(9-36)amide has direct effects on oxidative phosphorylation, intermediary metabolism, or any biochemical reactions for that matter (Box 1).

Box 1. Outstanding questions.

Is the suppression of hepatic glucose production by GLP-1(9-36)amide due to a direct effect of the peptide on hepatocytes or is it centrally mediated, for example, by receptors in the hypothalamus or nerve terminals in the portal vein? Are GLP-1(9-36)amide actions mediated through GLP-1 receptor, or by an alternative mechanism?

Could the expression of GLP-1 receptors be modulated by changes in the physiological state of the liver that facilitate the binding of GLP-1(9-36)amide?

Could some other G-protein coupled receptor, such as the glucagon receptor, serve as the hepatic GLP-1 receptor, via biochemical modification of the agonist and/or changes in the conformation of the receptor in liver?

Does GLP-1(9-36)amide suppress hepatic glucose production by modulating mitochondrial functions in hepatocytes as is implied for its actions on heart and vasculature?

Does GLP-1(9-36)amide, or peptides derived therefrom, mediate its mitochondrial actions of anti-oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation by signal transduction pathways conveyed by cell surface receptors or by its internalization into cells and direct targeting to mitochondria?

Does the endopeptidase NEP24.11, or similar endopeptidases, generate new bioactive peptides from GLP-1 in the target cells of its actions, or do endopeptidases simply degrade GLP-1 to inactive peptides?

Does the use of Dpp4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes impair important insulin-like actions of GLP-1 mediated by the cleavage product GLP-1(9-36)amide?

Based on the existence of insulinomimetic, and absence of insulinotropic, actions of GLP-1(9-36)amide, would it be a suitable therapy for the treatment of obesity related diabetes when insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia prevail? Would GLP-1(9-36)amide serve as an “insulin sensitizer” in pharmacologic doses providing insulin-like actions in the presence of severe insulin resistance?

An additional question that remains unanswered at present is whether GLP-1 receptors are expressed in the liver. The evidence on this matter is controversial, in that GLP-1(9-36)amide binds only poorly to GLP-1 receptor. This suggests that if receptors are involved in sensing GLP-1 (9-36)amide actions on the liver, they must be novel receptors distinct from the known GLP-1 receptor. Moreover, it remains to be determined whether GLP-1(9-36) acts on putative novel receptors to convey signals to mitochondria or whether GLP-1(9-36)amide, and/or peptides derived therefrom by further endopeptidase cleavages, enter hepatocytes and target the mitochondria. Likewise, the physiological state of the liver such as inflammation or lipid accumulation may condition the expression of GLP-1 receptors, novel or otherwise, and thereby activate downstream signaling mechanism that convey GLP-1 actions..

The discovery of insulinomimetic actions of the GLP-1 metabolite, GLP-1(9-36)amide in heart, vasculature, and possibly liver, raises implications regarding the use of Dpp4 inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes. Prevention of the formation of GLP-1(9-36)amide may ultimately augment oxidative stress in heart, vasculature, liver, and promote hepatic glucose production -untoward effects that would be undesirable in the treatment of obesity-related diabetes. Potent, short acting Dpp4 inhibitors taken at the time of meals may provide brief stimulation of insulin secretion by increasing levels of insulinotropic GLP-1(7-36)amide, allowing escape from Dpp4 inhibition and the intermittent production of insulinomimetic GLP-1(9-36)amide during interprandial periods. Discovery in the area of insulin-like actions of GLP-1 derived peptides on insulin-sensitive tissues has occurred only recently and much is yet to be learned about the multiple actions of GLP-1-related peptide hormones.

Acknowledgments

We thank Violeta Stanojevic and Melissa Thomas for thoughtful comments on the manuscript. Supported in part by an Investigator Initiated Studies Program grant from Merck & Company and by USPHS DK030834 to JFH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kieffer TJ, Habener JF. The glucagon-like peptides. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:876–913. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.6.0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estall JL, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like Peptide-2. Annu Rev Nutr. 2006;26:391–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang G, Zhang BB. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E671–678. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00492.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovshin JA, Drucker DJ. Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:262–269. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abu-Hamdah R, Rabiee A, Meneilly GS, Shannon RP, Andersen DK, Elahi D. Clinical review: The extrapancreatic effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 and related peptides. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1843–1852. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deacon CF. Circulation and degradation of GIP and GLP-1. Horm Metab Res. 2004;36:761–765. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plamboeck A, Holst JJ, Carr RD, Deacon CF. Neutral endopeptidase 24.11 and dipeptidyl peptidase IV are both mediators of the degradation of glucagon-like peptide 1 in the anaesthetised pig. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1882–1890. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1847-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368:1696–705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holz GG, 4th, Kühtreiber WM, Habener JF. Pancreatic beta-cells are rendered glucose-competent by the insulinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide-1(7-37) Nature. 1993;361:362–365. doi: 10.1038/361362a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beinborn M, Worrall CI, McBride EW, Kopin AS. A human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor polymorphism results in reduced agonist responsiveness. Regul Pept. 2005;130:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deacon CF, Nauck MA, Toft-Nielsen M, Pridal L, Willms B, Holst JJ. Both subcutaneously and intravenously administered glucagon-like peptide I are rapidly degraded from the NH2-terminus in type II diabetic patients and in healthy subjects. Diabetes. 1995;144:1126–1131. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.9.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen L, Deacon CF, Orskov C, Holst JJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-36)amide is transformed to glucagon-like peptide-1-(9-36)amide by dipeptidyl peptidase IV in the capillaries supplying the L cells of the porcine intestine. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5356–5363. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roques BP, Noble F, Daugé V, Fournié-Zaluski MC, Beaumont A. Neutral endopeptidase 24.11: structure, inhibition, and experimental and clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1993;45:87–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hupe-Sodmann K, McGregor GP, Bridenbaugh R, Göke R, Göke B, Thole H, Zimmermann B, Voigt K. Characterisation of the processing by human neutral endopeptidase 24.11 of GLP-1(7-36) amide and comparison of the substrate specificity of the enzyme for other glucagon-like peptides. Regul Pept. 1995;58:149–156. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(95)00063-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne JA, Meara NJ, Rayner AC, Thompson RJ, Knisely AS. Lack of hepatocellular CD10 along bile canaliculi is physiologic in early childhood and persistent in Alagille syndrome. Lab Invest. 2007;87:1138–1148. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan JM, Meneilly GS, Habener JF, Elahi D. Glucagon-like peptide-1 augments insulin-mediated glucose uptake in the obese state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002:3768–3773. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.8.8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan AS, Egan JM, Habener JF, Elahi D. Insulinotropic hormone glucagon-like peptide-1-(7-37) appears not to augment insulin-mediated glucose uptake in young men during euglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2399–2404. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.7.4988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee YS, Shin S, Shigihara T, Hahm E, Liu MJ, Han J, Yoon JW, Jun HS. Glucagon-like peptide-1 gene therapy in obese diabetic mice results in long-term cure of diabetes by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing hepatic gluconeogenesis. Diabetes. 2007;56:1671–1479. doi: 10.2337/db06-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding X, Saxena NK, Lin S, Gupta NA, Anania FA. Exendin-4, a glucagon-like protein-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, reverses hepatic steatosis in ob/ob mice. Hepatology. 2006;43:173–181. doi: 10.1002/hep.21006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samson SL, Gonzalez EV, Yechoor V, Bajaj M, Oka K, Chan L. Gene therapy for diabetes: metabolic effects of helper-dependent adenoviral exendin 4 expression in a diet-induced obesity mouse model. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1805–1812. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redondo A, Trigo MV, Acitores A, Valverde I, Villanueva-Penacarillo ML. Cell signaling of the GLP-1 action in liver. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;204:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikolaidis LA, Elahi D, Shen YT, Shannon RP. Active metabolite of GLP-1 mediates myocardial glucose uptake and improves left ventricular performance in conscious dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2401–H2408. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00347.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ban K, Noyan-Ashraf MH, Hoefer J, Bolz SS, Drucker DJ, Husain M. Cardioprotective and vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor are mediated through both glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor-dependent and -independent pathways. Circulation. 2008;117:2340–2350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ossum A, van Deurs U, Engstrom T, Jensen JS, Treiman M. The cardioprotective and inotropic components of postconditioning effects of GLP-1 and GLP-1(9-36)a in an isolated rat heart. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonne DP, Engstrøm T, Treiman M. Protective effects of GLP-1 analogues exendin-4 and GLP-1(9-36) amide against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat heart. Regul Pept. 2008;146:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szeto H. Cell-permeable, mitochondrial-targeted, peptide antioxidants. AAPS J. 2006;21:E277–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02854898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu D, Soong Y, Zhao GM, Szeto HH. A highly potent peptide analgesic that protects against ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial stunning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H783–791. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00193.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song W, Shin J, Lee J, Kim H, Oh D, Edelberg JM, Wong SC, Szeto H, Hong MK. A potent opiate agonist protects against myocardial stunning during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in rats. Coron Artery Dis. 2005;16:407–410. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200509000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green BD, Hand KV, Dougan JE, McDonnell BM, Cassidy RS, Grieve DJ. GLP-1 and related peptides cause concentration-dependent relaxation of rat aorta through a pathway involving KATP and cAMP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;478:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nathanson D, Erdogdu O, Pernow J, Zhang Q, Nystrom T. Endothelial dysfunction induced by triglycerides is not restored by exenatide in rat conduit arteries ex vivo. Regul Pept. 2009;157:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beinborn M, Worral CI, McBride EW, Kopin AS. A human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor polymorphism results in reduced agonist responsiveness. Regul Pept. 2005;130:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elahi D, Egan JM, Shannon RP, Meneilly GS, Khatri A, Habener JF, Andersen DK. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (9-36) amide, cleavage product of glucagon-like peptide-1 (7-36) is a glucoregulatory peptide. Obesity. 2008;16:1501–1509. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vahl TP, Paty BW, Fuller BD, Pridgeon RL, D’Alessio DA. Effects of GLP-1-(7-37), and GLP-1-(9-36)NH2 on intravenous glucose tolerance and glucose-induced insulin secretion in healthy humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1772–1779. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randle PJ. Regulatory interactions between lipids and carbohydrates: the glucose fatty acid cycle after 35 years. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1998;14:263–283. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0895(199812)14:4<263::aid-dmr233>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vahl TP, Tauchi M, Durler TS, Effers EE, Fernandes TM, Bitner RD, Ellis KS, Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Herman JP, D’Alessio DA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptors expressed on nerve terminals in the portal vein mediate the effects of endogenous GLP-1 on glucose tolerance in rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4965–4973. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inonut V, Zheng D, Stefanovski D, Bergman RN. Exenatide can reduce glucose independent of islet hormones or gastric emptying. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E269–E277. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90222.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandoval DA, Bagnol D, Woods SC, D’Alessio DA, Seeley RJ. Arcuate glucagon-line peptide 1 receptors regulate glucose homeostasis but not food intake. Diabetes. 2008;57:2046–2054. doi: 10.2337/db07-1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishizawa M, Nakabayashi H, Dawai K, Ito T, Dawakami S, Nakagawa A, mNiijima A, Uchida K. The hepatic vagal reception of intraportal GLP-1 is via receptor different from the pancreatic GLP-1 receptor. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;80:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dardevet D, Moore MC, DiCostanzo CA, Farmer B, Neal DW, Snead W, Lautz M, Cherrington AD. Insulin secretion-independent effects of GLP-1 on canine liver glucose metabolism do not involve portal vein GLP-1 receptors. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G806–G814. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00121.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villanueva-penacarillo ML, Delgado E, Trapote MA, Alcantara A, Clemente F, Lugue MA, Perea A, Valverde I. Glucagon-like peptide-1 binding to rat hepatic membranes. J Endocrinol. 1995;146:183–189. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1460183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li WC, Horb ME, Tosh D, Slack JM. In vitro transdifferentiation of hepatoma cells into functional pancreatic cells. Mech Dev. 2005;122:837–847. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aviv V, Meivar-Levy I, Rachmut IH, Rubinek T, Mor E, Ferber S. Exendin-4 promotes liver cell proliferation and enhances PDX-1-induced liver to pancreas transdifferentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017608. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bullock BP, Heller RS, Habener JF. Tissue distribution of messenger ribonucleic acid encoding the rat glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2968–2978. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blackmore PF, Mojsov S, Exton JH, Habener JF. Absence of insulinotropic glucagon-like peptide-1(7-37) receptors on isolated rat liver hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 1991;283:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80541-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flock G, Baggio LL, Longuet C, Drucker JJ. Incretin receptors for glucagon-like peptide 1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide are essential for the sustained metabolic actions of vildagliptin in mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:3006–3013. doi: 10.2337/db07-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korner M, Stockli M, Waser B, Reubi JC. GLP-1 receptor expression in human tumors and human normal tissues: potential for in vitro targeting. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:736–743. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horbinski C, Chu CT. Kinase signaling cascades in the mitochondrion: a matter of life or death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Affaitati A, Cardone L, de Cristofaro T, Carlucci A, Ginsberg MD, Varrone S, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV, Feliciello A. Essential role of A-kinase anchor protein 121 for cAMP signaling to mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4286–4294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bijur GN, Jope RS. Rapid accumulation of Akt in mitochondria following phosphatidylinositol 3kinase activation. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1427–1435. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Demers A, McNicoll N, Febbraio M, Servant M, Marleau S, Silverstein R, Ong H. Identification of the growth hormone-releasing peptide binding site in CD36: a photoaffinity cross-linking study. Biochem J. 2004;382:417–424. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore KJ, El Khoury J, Medeiros LA, Terada K, Geula C, Luster AD, Freeman MW. A CD36-initiated signaling cascade mediates inflammatory effects of beta-amyloid. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47373–47379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Isenberg JS, Jia Y, Fukuyama J, Switzer CH, Wink DA, Roberts DD. Thrombospondin-1 inhibits nitric oxide signaling via CD36 by inhibiting myristic acid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15404–15415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701638200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemire BD, Frankenhauser C, Baker A, Schatz Z. The mitochondrial targeting function of randomly generated peptide sequences correlates with predicted helical amphiphilicity. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20205–20215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamada H, Chounan R, Higashi Y, Kurihara N, Kido H. Mitochondrial targeting sequence of the influenza A virus PB1-F2 protein and its function in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brun C, Philip-Couderc P, Raggenbass M, Roatti A, Baertschi AJ. Intracellular targeting of truncated secretory peptides in the mammalian heart and brain. FASEB J. 2006;20:732–734. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4338fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, Sprung R, Tang Y, Ball H, Sangras B, Kim SC, Falck JR, Peng J, Gu W, Zhao Y. Lysine propionylation and butyrylation are novel post-translational modifications in histones. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:812–819. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700021-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chauvin S, Poulain FE, Ozon S, Sobel A. Palmitoylation of stathmin family proteins domain A controls Golgi versus mitochondrial subcellular targeting. Biol Cell. 2008;100:577–589. doi: 10.1042/BC20070119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duvnjak M, Lerotic I, Barsic N, Tomasic V, Virovic V, Jukic L, Velagic V. Pathogenesis and management issues for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4539–4550. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i34.4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC. Mechanistic insights into diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1729–1738. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park TS, Yamashita H, Blaner WS, Goldberg IJ. Lipids in the heart: a source of fuel and a source of toxins. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:277–282. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32814a57db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wakelam JJO, Murphy GJ, Hruby VJ, Houslay MD. Activation of two signal-transduction systems in hepatocytes by glucagon. Nature. 1986;323:68–71. doi: 10.1038/323068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]