Abstract

In the past few years, the field of cancer immunotherapy has made great progress and is finally starting to change the way cancer is treated. We are now learning that multiple negative checkpoint regulators (NCR) restrict the ability of T-cell responses to effectively attack tumors. Releasing these brakes through antibody blockade, first with anti-CTLA4 and now followed by anti-PD1 and anti-PDL1, has emerged as an exciting strategy for cancer treatment. More recently, a new NCR has surfaced called V-domain immunoglobulin (Ig)-containing suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA). This NCR is predominantly expressed on hematopoietic cells, and in multiple murine cancer models is found at particularly high levels on myeloid cells that infiltrated the tumors. Preclinical studies with VISTA blockade have shown promising improvement in antitumor T-cell responses, leading to impeded tumor growth and improved survival. Clinical trials support combined anti-PD1 and anti-CTLA4 as safe and effective against late-stage melanoma. In the future, treatment may involve combination therapy to target the multiple cell types and stages at which NCRs, including VISTA, act during adaptive immune responses.

Introduction

The concept of immunosurveillance for cancer was proposed by Burnet (1), who posited that transformed cells continually arise in the body as a result of mutation and are usually detected and then deleted by the immune system. Cognizant of this theory, decades have been spent attempting, and largely failing to improve the immunosurveillance against malignancies that have escaped eradication, although the concept of immunoediting has gained broad acceptance. The editors of Science chose cancer immunotherapy as Breakthrough of the Year for 2013 (2), and the journal Nature has devoted the entire 2013 year-end Outlook supplement to cancer immunotherapy (3), both of which are reflective of some of the revolutionary clinical responses being observed by agents that relieve immune suppression and allow immunosurveillance to eradicate cancer.

Negative Checkpoint Regulators, New and Old

Molecules that promote or interfere with the mounting of protective antitumor immunity are under intensive study. Many of these molecules are members of the B7 family, and they act as rheostats that control the threshold for whether a given T-cell receptor (TCR) interaction leads to activation and/or anergy. CD28 is one such molecule, as when it binds to its ligands, CD80 or CD86, it facilitates fulminant T-cell activation (4, 5). Clinical experience with an agonistic antibody to CD28 in 6 healthy volunteers has shown that unimpeded signaling through CD28 results in a massive cytokine storm with a litany of immune-related toxicities (irT; ref. 6). Negative checkpoint regulators (NCR) are molecules that temper T-cell activation and render cell-mediated immune responses within constraints that are safe to the host. The prototypical NCR is cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)–associated antigen 4 (CTLA4), which interacts with CD80 and CD86 (Fig. 1). This T-cell membrane protein plays a central role as an NCR critical in tempering irT that would result in its absence. Mice that are genetically deficient in CTLA4 develop fatal systemic lymphoproliferative disease with multiorgan lymphocytic infiltration and damage by 3 to 4 weeks of age (7). The importance of tempering CD28 signaling can be seen readily when negative regulators are genetically deleted or blocked (anti-CTLA4). These and other studies underscored the importance of NCRs in tempering immunity, and have offered the prospects of amplifying immune responses at will when the clinical need arises.

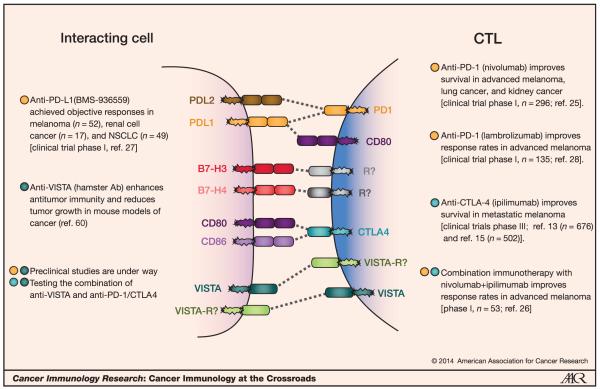

Figure 1.

Negative checkpoint regulators in the TME. The major NCRs in the Ig superfamily are shown in CTL and interacting cell type (e.g., tumor cell, myeloid cell, etc.). Blocking antibodies toward these targets is showing great promise in immunotherapy.

The complex nature of the NCR pathways that control the magnitude of T cell–mediated inflammation is only now being appreciated. Many receptors and ligands have multiple binding partners (Fig. 1). Furthermore, many of the interactions are bidirectional with regard to signaling, rendering the assignment of ligand and receptor ambiguous or irrelevant. As such, many of the so-called ligands transduce signals themselves. For the purpose and context of this Crossroads overview, “receptor” refers to the surface protein on CTLs and “ligand” is the surface protein on all other cell types that interact with CTLs. In addition to engaging CD28 and CTLA4, CD80 binds to the ligand PDL1, which then transduces a negative signal (Fig. 1; ref. 8). B-lymphocyte and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) signals negatively following interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM; ref. 9), whereas HVEM itself has positive activity (10). Assignment of all family members within the super immunoglobulin (Ig) family has even been breached, as HVEM, a ligand for BTLA, is in the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF). A further cross-family interaction occurs between B7-H6 and natural killer (NK) cell p30-related protein (NKp30; ref. 11). The complexity of NCRs of the CD28-B7 family must be considered when targeting one or more of its members for therapy.

CTLA4

CTLA4 competes with CD28 for interaction with CD80 and CD86 (Fig. 1). Early after T-cell activation, CTLA4 expression on the cell surface is increased as a result of both increased mRNA expression and release from intracellular depots. CTLA4 can bind CD80 and CD86 at higher affinity than CD28. This acts centrally to limit the extent of T-cell activation by competing with CD28 engagement and interrupting TCR signaling.

The first anti-CTLA4 human monoclonal antibody (mAb), ipilimumab, was approved in 2011 by the FDA for use in metastatic melanoma (12). Following activity in phase II clinical trials, success for ipilimumab was reported in a large phase III clinical trial involving treatment of 676 patients with metastatic melanoma, who had undergone previous failed treatment (13). Patients received 3 mg/kg of ipilimumab with or without a vaccine derived from the melanosomal protein glycoprotein 100 (gp100), or were treated with gp100 alone as an active control. Median overall survival was 10.0 months in the combination group (P < 0.001), and 10.1 months with ipilimumab alone (P = 0.003), as compared with 6.4 months in the control group. Furthermore, the 1- and 2-year survival rates increased from 25% and 14% in the controls to 46% and 24% with ipilimumab. It is of note that some patients exhibited delayed responses, sometimes with tumor progression before tumor regression. Although ipilimumab is generally believed to act by releasing the brakes on antitumor T-cell responses (14), we speculate that a major therapeutic mechanism of action may be ablation of regulatory T cells (Treg) within the tumor microenvironment (TME).

These results broke new ground as the first immunotherapeutic strategy showing improved survival in metastatic melanoma in a phase III trial. A subsequent phase III study compared a higher dose of ipilimumab (10 mg/kg) plus dacarbazine to dacarbazine alone in 502 patients with previously untreated metastatic melanoma (15). The results mirrored the first phase III trial, achieving longer survival times (11.2 vs. 9.1 months) and higher survival rates at 1 year (47.3% vs. 36.3%), 2 years (28.5% vs. 17.9%), and 3 years (20.8% vs. 12.2%). With the efficacy of CTLA4 blockade established, clinical trials are currently addressing ways to build on these results. As discussed below, combination therapies will likely improve the efficacy of immunomodulatory approaches and will be a driving concept of future studies in this field.

PD1

PD1 is a critical NCR, which mitigates inflammation to maintain peripheral tolerance (Fig. 1). Upon activation, T cells and B cells upregulate the NCR PD1, which becomes detectable from the cell surface by 24 hours (16, 17). PD1 then forms negative costimulatory microclusters associated with phosphatase SHP2 (Src homology 2 domain–containing tyrosine phosphatase 2) and TCRs, leading to the dephosphorylation of TCRs and suppression of T-cell functions (18). One of the PD1 ligands, PDL2, can be induced on dendritic cells (DC), monocytes, and macrophages (19). In contrast, the other PD1 ligand, PDL1, is broadly and constitutively expressed on immune cells and throughout the body (Fig. 1; ref. 19). PDL1 expression can be increased by stimulation with type I or II interferons (IFN) on T cells, macrophages, and tumors (20, 21). Peripheral PDL1 is thought to be important in dampening T cells to prevent autoimmune or bystander damage in tissues, but it is also implicated in T-cell exhaustion and immune-cell evasion by tumors.

Many studies have described the correlation of PDL1 with invasiveness, metastasis, and poor prognosis. It appears well established that high PDL1 is generally associated with a poor outcome (22, 23). PDL1 expression is upregulated by IFNγ, as a defense against collateral damage. It has been suggested that IFNγ produced by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) may be inducing PDL1 expression, which in turn suppresses TIL activity, or leads to T-cell anergy or exhaustion (24). Thus, PDL1 expression may be a result of TIL infiltration, or even an indicator of tumors for which useful antitumor responses may be generated.

Early clinical trials targeting the PD1 pathway with anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1 have generated much excitement. In phase I trials, compelling rates of objective responses have been achieved. Of particular note are three large phase I trials, which assessed Bristol-Myers Squibb’s anti-PD1 (BMS-936558, nivolumab) and anti-PDL1 (BMS-936559), and Merck’s anti-PD1 mAb (MK-3475, lambrolizumab). In the first trial, 296 patients with advanced melanoma, non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), castration-resistant prostate cancer, renal cell cancer, or colorectal cancer received anti-PD1 over multiple escalation doses. Long-term durable responses were achieved in 18% to 28% in NSCLC, melanoma, and renal cell cancer (25). Interestingly, there was evidence of improved efficacy in patients whose tumors expressed PDL1 (objective responses in 0 of 17 PDL1− tumors and 9 of 25 PDL1+ tumors). A similar finding was observed with patients treated concurrently with ipilimumab and nivolumab (26). If this correlation holds true, it remains to be seen whether PDL1 expression is a general marker of tumors with immune interaction that are sensitive to immunotherapy by any NCR, or whether this is a specific requirement for PD1 blockade. The concurrent dose-escalating phase I trial for blockade of PDL1 (BMS-936559) induced durable tumor regression at rates of 6% to 17% in NSCLC, melanoma, and renal cell cancer (27). A recent clinical trial tested another anti-PD1 formulation (lambrolizumab) in 135 patients with advanced melanoma at 10 mg/kg achieving a response rate of over 50% (28).

B7-H3

B7-H3 is another B7 family member that has been implicated as a regulator of tumor immunosurveillance (Fig. 1). Expression of B7-H3 mRNA is broad, detectable in most body tissues and some tumor cell lines (29), but protein expression is detected at relatively low levels. Peripheral blood leukocytes do not express B7-H3, but it can be induced on monocytes, DCs, and T cells by stimulation (30). Like PD1, the activities of B7-H3 have faced controversy. Both in mice and humans, there are reports that show B7-H3 acts as either a costimulatory molecule (29, 31) or a NCR (30, 32, 33). Contributing to the dilemma is the inability to credibly identify the receptor for B7-H3, a feature problematic to a number of members of the NCR family. However, there are data suggesting that the receptor for B7-H3 is expressed on activated T cells and NK cells (29). A receptor called triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-like transcript 2 (TLT-2) has been proposed (34), as antibodies against either TLT-2 or B7-H3 inhibited contact hypersensitivity. However, a subsequent study did not find evidence of this interaction (33). The basis for these different findings is not clear; it is possible that different isoforms of B7-H3 may interact with more than one receptor.

As might be expected from both stimulatory and inhibitory activities being detected for B7-H3, this molecule has been reported to have either immune-enhancing or immune-inhibitory impact in murine cancer models. Murine tumor cell lines transfected with B7-H3 result in increased CD8 responses, and therefore grow poorly in vivo or are rejected (35, 36). However, a large number of studies have shown that B7-H3 has detrimental effects in cancer, as it promotes tumor progression and metastasis, and reduces host survival (37). In humans, B7-H3 expression has been observed on many tumor types at varying frequencies (37). In gastric and pancreatic cancer, B7-H3 had a positive effect on survival and infiltration by CTL (38, 39). Interestingly, in clear cell renal cancer, B7-H3 expression was observed on the vasculature in 95% of specimens, but only 17% showed tumor-cell expression (40). Both vasculature and tumor-cell expression were associated with poor outcome. In NSCLC, the soluble form of B7-H3 was found to be a particularly useful biomarker for poor prognosis—better than even more traditional biomarkers such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA; ref. 41). As argued by Loos and colleagues (37), given the understanding that the level of expression of costimulatory molecules may influence their functional effect (42), both the intensity of staining, and the cell type involved should be taken into account in these kinds of studies.

B7-H4

Another promising NCR for cancer immunotherapy is B7-H4 (Fig. 1), whose binding partner remains unknown. B7-H4 is also known as B7x, B7 superfamily member 1 (B7-S1), and V-set domain–containing T-cell activation inhibitor 1 (vtcn1). B7-H4 is expressed on B cells and other antigen-presenting cells (APC). IL6 and IL10 increase its expression, while granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL4 reduce its expression (43). In murine models, B7-H4 has been shown to inhibit T-cell activation and cytokine production in vitro and in vivo, by antibody blockade, Fc fusion protein, and/or transfection on APCs (44–46). A role for B7-H4 on innate cells has been elucidated, as B7-H4 knockout mice are more resistant to Listeria monocytogenes infection, even in the absence of T cells in double knockout mice with recombination-activating gene-1 deficiency. The resistance to infection seems to be related to the elevated neutrophil numbers due to increased proliferation of neutrophil progenitors (47).

B7-H4 is an Ig protein with a well-established role as a biomarker for progression in cancers. B7-H4 is detected on a variety of tumors, including melanoma, NSCLC, prostate, ovary, stomach, pancreas, breast, esophagus, and kidney cancers, with expression on infiltrating myeloid cells, vasculature, and tumor cells (Fig. 1; refs. 43, 48). Most studies show a potential prognostic role correlating B7-H4 expression with tumor-stage grade biologic behavior, recurrence, and survival rate. The biologic activity, nonoverlapping expression pattern, and correlation with cancer progression are rationale for the development of B7-H4 as a new target for immunotherapy.

In addition to the CD28-B7 family of proteins, other Ig superfamily proteins may be targets for tumor immunotherapy. Two promising candidates are lymphocyte-activated gene-3 (LAG-3) and T-cell Ig- and mucin-domain–containing molecule-3 (TIM-3). LAG-3 is induced upon T-cell activation and binds major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, leading to inhibition of TCR-induced calcium fluxes (49, 50). TIM-3 is expressed on activated T-helper 1 (Th1) cell subsets and interacts with Galectin-9, leading to suppression of macrophages and apoptosis of T cells (51, 52). Importantly, these molecules are expressed on exhausted T cells, and there is evidence that the activity of LAG-3 and TIM-3 may be synergistic with PD1 in this context (53–55).

VISTA—A New Immunomodulatory Target with Broad-Spectrum Activities

A new target for cancer immunotherapy is the Ig superfamily member V-domain Ig-containing suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA, Entrez: 64115), also known as C10orf54, differentiation of ESC-1 (Dies1), platelet receptor Gi24 precursor, or PD1 homolog (PD1H). The extracellular domain of VISTA is most similar to that of PDL1; however, VISTA possesses some unusual structural features. VISTA does not cluster with the CD28-B7 family at standard confidence limits, and therefore is rather weakly associated with the rest of the group (56). Although studies using Fc fusion proteins clearly show that VISTA has ligand activity (56, 57), receptor-like signaling activity has also been described (58). Indeed, the extracellular domain consists of a single IgV (variable region) domain, like the receptors in the family. Additionally, a recent study utilizing VISTA knockout mice demonstrated that endogenous VISTA has inhibitory effects both as a ligand on APCs and as a receptor on T cells (58). The binding partner(s) of VISTA responsible for these activities is currently unknown (Fig. 1).

In both mice (56) and humans (57), VISTA is expressed predominantly on hematopoietic cells with the greatest densities on myeloid and granulocytic cells, and weaker expression on T cells. Similar to some members of the B7-CD28 family (e.g., PDL1; ref. 8), T cells both express and respond to VISTA. VISTA–Fc fusion protein and cellular overexpression of VISTA are suppressive to T-cell activation, proliferation, and cytokine production (56, 57). In vivo blockade of VISTA was found to enhance the T-cell response to OVA, and to exacerbate the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE; ref. 56). Interestingly, in a separate study, blockade with anti-VISTA and VISTA–Fc fusion protein was found to inhibit acute graft-versus-host disease (59). This immunosuppressive effect of VISTA may be due to the ability of specific anti-VISTA antibodies to deplete VISTA-bearing cells.

Both naïve and antigen-experienced cells are sensitive to VISTA-induced suppression (56, 57), which suggests that in addition to constitutive expression of VISTA, the receptor may be constitutively expressed on resting T cells. Therefore, we speculate that VISTA may act as a rheostat to prevent promiscuous resting T-cell responses to self-antigens. In support of this notion, findings from Flies and colleagues (58) and our own studies show that mice lacking VISTA expression have elevated frequencies of activated T cells with a systemic proinflammatory phenotype.

VISTA in Cancer

The potential of VISTA to act as an NCR in the setting of cancer was first demonstrated by Wang and colleagues in a murine model of methylcholanthrene 105 (MCA105)–induced fibrosarcoma (56). MCA105 tumor cells engineered to overexpress VISTA-RFP were shown to grow in animals with immunity protective against the growth of control MCA105 cells. More recently, Le Mercier and colleagues described elevated VISTA expression on leukocytes within the TME and tumor-draining lymph nodes in murine cancer models (60). They also examined the use of an anti-VISTA mAb for intervention and found that VISTA blockade impaired tumor growth, with particularly dramatic results when used in combination with a tumor vaccine (60). Within the TME, a shift was generated toward antitumor immunity with elevated infiltration, proliferation, and T-cell effector function.

As compared with the activity of anti-CTLA4, anti-PD1, and anti-PDL1 in preclinical studies, the VISTA blockade data appear compelling (61–63). Similar to the findings of Wang and colleagues (56), Sorensen and colleagues reported melanoma regression and long-term survival rates of 30% to 40% in a study of CTLA4 blockade in combination with CD40 stimulation and the administration of an adenoviral vaccine (62).

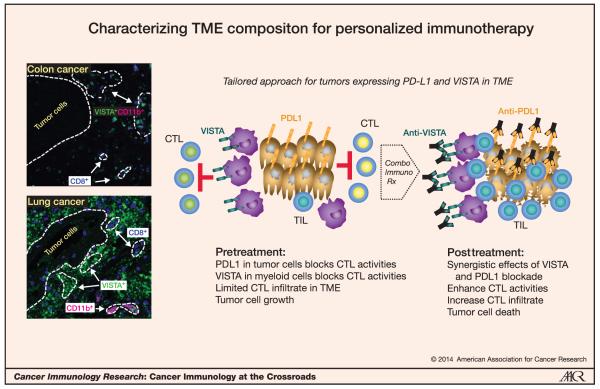

Following the promising studies of VISTA in murine models of cancer, we initiated studies to evaluate VISTA expression in human cancers. As anticipated, we did not detect VISTA expression in a commercially available panel of cDNAs isolated from human nonhematopoietic tumor cell lines (data not shown; Human Cell Line MTC Panel; Clontech). The mouse data suggest that VISTA is exclusively expressed on leukocytes infiltrating the tumor. Therefore, VISTA expression was examined on colon and lung cancer lesions by fluorescence-based multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) as previously described using the GG8 clone of anti-human VISTA (57). When present, VISTA expression was confined predominantly to the infiltrating CD11b+ cells in the TME of colon cancer lesions, whereas infiltrating VISTA+ cells in some cases, but not others, expressed CD11b in lung cancer cells (Fig. 2). In all examined cases, we did not observe coexpression of VISTA and CD8 in infiltrating cells. However, lower VISTA expression levels on CD8+ T cells may be below the detection limits of this antibody by IHC staining. As the composition of the immune-cell infiltrates varies between tumors within the same cancer site, and in tumors of different cancer types (Fig. 2), we would predict that a frank myeloid infiltrate in tumor lesions would express high levels of VISTA. Future studies in larger cohorts of patients will be needed to identify tumor characteristics that may be associated with VISTA expression in the TME.

Figure 2.

Understanding TME composition for personalized combination of immunotherapeutic agents. Left, expression of VISTA, CD8, and CD11b was codetected in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections of colon and lung cancer tumor lesions. In these merged image panels, colocalization of VISTA (green) and CD11b (magenta) signal appears white. Right, tailored approach for tumor expressing PDL1 and VISTA in different cellular compartments of the TME. VISTA and PDL1 interfere with different subsets of CTL and distinctly affect their activities. Synergistic effects of dual VISTA and PDL1 blockade would be expected to enhance CTL and activities and boost antitumoral immunity.

Two particularly interesting points for VISTA immunotherapy from observations in the mouse models are that VISTA blockade was effective without any detectable expression of VISTA on the tumor cells, and that VISTA blockade works even in the presence of high PDL1 expression (60). The lack of requirement for VISTA expression on the tumor suggests that VISTA blockade may have broad clinical applicability, and is potentially an advantage over PD1 or PDL1 blockade, which may require expression on the target tumor (25). Although PDL1 may shield tumor cells from immunosurveillance, VISTA blockade is still sufficient to allow antitumor activity to develop within the TME. These data suggest that VISTA activity in the TME is important for antitumor immunity, and that VISTA blockade may be a promising immunotherapy strategy. Because the VISTA and PD1 checkpoint pathways are independent, there may be potential synergy when they are targeted in combination.

Personalizing Anti-VISTA Approaches in Cancer Immunotherapy

Strategies for the use of specific NCR-based immunotherapy will be guided by the signature of NCRs that are observed within the TME (Fig. 2). This would involve screening of individual patients for markers that allow tailored blockade to their specific tumor—for example PD1 blockade for patients with tumors that are PDL1 rich. Likewise, greater efficacy may be achieved by introducing NCR blockade into a treatment regimen both within the period for the best therapeutic window—before tumors have undergone extensive immunoediting and lost immunogenicity—and to achieve the best interactions with conventional treatments. By their nature of targeting proliferating cells, standard cancer treatments are often immunosuppressive—however, locally, these effects can be immunostimulatory (64, 65). Release of antigen and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) may recruit and activate TILs in the TME. In addition, homeostatic proliferation of leukocytes after depletion by chemotherapy may boost immune reactions stimulated concurrently. The timing of chemotherapy may be important for combination with immune-stimulating strategies. A recent trial combined ipilimumab with paclitaxel and carboplatin, either as a phased regimen (two doses of chemotherapy followed by four doses of chemotherapy plus ipilimumab) or concurrent (four doses of chemotherapy plus ipilimumab followed by two doses of chemotherapy; ref. 66). Interestingly, the phased regimen was effective in increasing progression-free survival, but the concurrent treatment was not.

As described above, the signaling pathways for VISTA, PD1, and CTLA4 are quite distinct. This suggests that first, failure of one blockade strategy does not necessarily mean that a patient would fail in the other strategy, and second that multiple blockade agents could be combined synergistically (Fig. 2). Two phase I trials testing either Merck’s anti-PD1 antibody lambrolizumab or the Bristol-Myers Squibb’s anti-PD1 nivolumab did not find a difference between patients who had already undergone ipilimumab therapy (anti-CTLA4) as compared with those who had not (28, 67). Combinations of PD1, CTLA4, VISTA, and/or LAG-3 blockades in preclinical studies support synergy (refs. 53, 68; Wang and colleagues; manuscript in preparation). A recent trial testing concurrent treatment of ipilimumab and nivolumab achieved a 40% overall objective response rate, and 53% at the highest dose groups (26). This indicates that the combination of antibodies for NCR blockade is both safe and clinically effective. The combination of GM-CSF with ipilimumab has shown a trend toward improved treatment tolerance and a significant improvement in survival in an ongoing phase II trial (69). One of the advantages of VISTA blockade as an immunotherapeutic strategy is that VISTA expression is not required on the tumor cells. Instead, the relevant VISTA-expressing cells seem to be the myeloid infiltrate (60). A combinatorial approach may use some permutation of the following: vaccine and ipilimumab to generate new clonal T-cell expansion, VISTA blockade to counteract some of the suppressive activity of the infiltrating myeloid cells, PD1 or PDL1 blockade to release anergic CTLs, and either B7-H4 or PD1 blockade to release the immunogenicity of the tumor (Fig. 2). As we learn more about the signature of NCR expression in the TME across human cancers, better strategies for combinatorial therapeutic intervention may be devised.

Future Directions

To improve the clinical effectiveness of NCR blockade, a clearer understanding of relevant biomarkers would be of great benefit. There is a need for markers both to predict how successful NCR blockade might be in a patient, and also to determine which NCR(s) should be targeted for tailored treatment. On the other end of the treatment process, biomarkers that indicate successful intervention are desirable. Treatment of cancers with NCR blockade can lead to delayed responses, sometimes even with tumor progression before tumor shrinkage. It has been proposed that RECIST criteria are potentially not the best criteria to use for evaluation of immunotherapeutic approaches, although the use of alternative criteria is controversial (1).

For VISTA, many questions still remain, not least being the identity of the receptor. As with B7-H3 and B7-H4, answering this question may be challenging, but would facilitate therapeutic development. Studies are under way examining how combination therapy of anti-VISTA with vaccines and/or blockade of other NCRs may be used to create synergistic responses. Although VISTA has been observed within the TME in human tumors, a comprehensive study of the correlation of VISTA expression with patient outcome in different tumor types is warranted. Antibodies targeting VISTA for cancer immunotherapy are already under development by Johnson & Johnson and VISTA may soon be a part of the immunotherapy revolution.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support This study was supported by AICR 12-1305 (R. Noelle and J. Lines), NIH R01AI098007 (R. Noelle), Wellcome Trust, Principal Research Fellowship (R. Noelle), R01CA164225 (L. Wang), and a Hitchcock Foundation pilot grant (L.F. Sempere).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest J.L. Lines, T. Broughton, L. Wang, and R. Noelle are consultant/advisory board members for Immunext.

References

- 1.Burnet FM. The concept of immunologic surveillance. In: Schwartz RS, editor. Immunological aspects of neoplasia. Karger; Boston, MA: 1970. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couzin-Frankel J. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342:1432–33. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gravitz L. Cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2013;504:S1–48. doi: 10.1038/504S1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azuma M, Cayabyab M, Buck D, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. CD28 interaction with B7 costimulates primary allogeneic proliferative responses and cytotoxicity mediated by small, resting T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;175:353–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.June CH, Ledbetter JA, Gillespie MM, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. T-cell proliferation involving the CD28 pathway is associated withcyclosporine-resistant interleukin 2 gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4472–81. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suntharalingam G, Perry MR, Ward S, Brett SJ, Castello-Cortes A, Brunner MD, et al. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, et al. CTLA-4 control over foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322:271–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27:111–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sedy JR, Gavrieli M, Potter KG, Hurchla MA, Lindsley RC, Hildner K, et al. B and T lymphocyte attenuator regulates T cell activation through interaction with herpesvirus entry mediator. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:90–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrop JA, McDonnell PC, Brigham-Burke M, Lyn SD, Minton J, Tan KB, et al. Herpesvirus entry mediator ligand (HVEM-L), a novel ligand for HVEM/TR2, stimulates proliferation of T cells and inhibits HT29 cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27548–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt CS, Baratin M, Yi EC, Kennedy J, Gao Z, Fox B, et al. The B7 family member B7-H6 is a tumor cell ligand for the activating natural killer cell receptor NKp30 in humans. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1495–503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron F, Whiteside G, Perry C. Ipilimumab. Drugs. 2011;71:1093–104. doi: 10.2165/11594010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarhini A, Lo E, Minor DR. Releasing the brake on the immune system: ipilimumab in melanoma and other tumors. Cancer Biother Radio-pharm. 2010;25:601–13. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O’Day S, M D JW, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agata Y, Kawasaki A, Nishimura H, Ishida Y, Tsubata T, Yakita H, et al. Expression of the PD-1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1996;8:765–72. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, June CH, Rilet JL. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J Immunol. 2004;173:945–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokosuka T, Takamatsu M, Kobayashi-Imanishi W, Hashimoto-Tane A, Azuma M, Saito T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1201–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamazaki T, Akiba H, Iwai H, Matsuda H, Aoki M, Tanno Y, et al. Expression of programmed death 1 ligands by murine T cells and APC. J Immunol. 2002;169:5538–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schreiner B, Mitsdoerffer M, Kieseier BC, Chen L, Hartung HP, Weller M, et al. Interferon-b enhances monocyte and dendritic cell expression of B7-H1 (PD-L1), a strong inhibitor of autologous T-cell activation: relevance for the immune modulatory effect in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;155:172–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SJ, Jang BC, Lee SW, Yang YI, Suh SI, Park YM, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is prerequisite to the constitutive expression and IFN-g-induced upregulation of B7-H1 (CD274) FEBS Lett. 2006;580:755–62. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seliger B, Quandt D. The expression, function, and clinical relevance of B7 family members in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:1327–41. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flies DB, Chen L. Modulation of immune response by B7 family molecules in tumor microenvironments. Immunol Invest. 2006;35:395–418. doi: 10.1080/08820130600755017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taube JM, Anders RA, Young GD, Xu H, Sharma R, McMiller TL, et al. Colocalization of inflammatory response with B7-H1 expression in human melanocytic lesions supports an adaptive resistance mechanism of immune escape. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:127ra37. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti–PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQM, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, et al. Safety and tumor responses with Lambrolizumab (Anti–PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapoval AI, Ni J, Lau JS, Wilcox RA, Flies DB, Liu D, et al. B7-H3: a costimulatory molecule for T cell activation and IFN-g production. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:269–74. doi: 10.1038/85339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prasad DVR, Nguyen T, Li Z, Yang Y, Duong J, Wang Y, et al. Murine B7-H3 is a negative regulator of T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2500–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Fraser CC, Kikly K, Wells AD, Han R, Coyle AJ, et al. B7-H3 promotes acute and chronic allograft rejection. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:428–38. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hashiguchi M, Inamochi Y, Nagai S, Otsuki N, Piao J, Kobori H, et al. Human B7-H3 binds to triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells–like transcript 2 (TLT-2) and enhances T cell responses. Open J Immunol. 2012;2:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leitner J, Klauser C, Pickl WF, Stockl J, Majdic O, Bardet AF, et al. B7-H3 is a potent inhibitor of human T-cell activation: no evidence for B7-H3 and TREML2 interaction. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1754–64. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashiguchi M, Kobori H, Ritprajak P, Kamimura Y, Kozono H, Azuma M. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell-like transcript 2 (TLT-2) is a counter-receptor for B7-H3 and enhances T cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802423105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo L, Chapoval AI, Flies DB, Zhu G, Hirano F, Wang S, et al. B7-H3 enhances tumor immunity in vivo by costimulating rapid clonal expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ cytolytic T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:5445–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun X, Vale M, Leung E, Kanwar JR, Gupta R, Krissansen GW. Mouse B7-H3 induces antitumor immunity. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1728–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loos M, Hedderich DM, Friess H, Kleeff J. B7-H3 and its role in antitumor immunity. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:683875. doi: 10.1155/2010/683875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loos M, Hedderich DM, Ottenhausen M, Giese NA, Laschinger M, Esposito I, et al. Expression of the costimulatory molecule B7-H3 is associated with prolonged survival in human pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:463–73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu CP, Jiang JT, Tan M, Zhu YB, Ji M, Xu KF, et al. Relationship between co-stimulatory molecule B7-H3 expression and gastric carcinoma histology and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:457–59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crispen PL, Sheinin Y, Roth TJ, Lohse CM, Kuntz SM, Frigola X, et al. Tumor cell and tumor vasculature expression of B7-H3 predict survival in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5150–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang G, Xu Y, Lu X, Huang H, Zhou Y, Lu B, et al. Diagnosis value of serum B7-H3 expression in non–small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;66:245–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tirapu I, Huarte E, Guiducci C, Arina A, Zaratiegui M, Murillo O, et al. Low surface expression of B7–1 (CD80) is an immunoescape mechanism of colon carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2442–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi KH, Chen L. Fine tuning the immune response through B7-H3 and B7-H4. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasad DVR, Richards S, Mai XM, Dong C. B7S1, a novel B7 family member that negatively regulates T cell activation. Immunity. 2003;18:863–73. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sica GL, Choi IH, Zhu G, Tamada K, Wang SD, Tamura H, et al. B7-H4, a molecule of the B7 family, negatively regulates T cell immunity. Immunity. 2003;18:849–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zang X, Loke P, Kim J, Murphy K, Waitz R, Allison JP. B7×: a widely expressed B7 family member that inhibits T cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10388–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1434299100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu G, Augustine MM, Azuma T, Luo L, Yao S, Anand S, et al. B7-H4–deficient mice display augmented neutrophil-mediated innate immunity. Blood. 2009;113:1759–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seliger B, Marincola FM, Ferrone S, Abken H. The complex role of B7 molecules in tumor immunology. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:550–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hannier S, Tournier M, Bismuth G, Triebel F. CD3/TCR complex–associated lymphocyte activation gene-3 molecules inhibit CD3/TCR signaling. J Immunol. 1998;161:4058–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baixeras E, Huard B, Miossec C, Jitsukawa S, Martin M, Hercend T, et al. Characterization of the lymphocyte activation gene 3-encoded protein. A new ligand for human leukocyte antigen class II antigens. J Exp Med. 1992;176:327–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monney L, Sabatos CA, Gaglia JL, Ryu A, Waldner H, Chernova T, et al. Th1-specific cell surface protein Tim-3 regulates macrophage activation and severity of an autoimmune disease. Nature. 2002;415:536–41. doi: 10.1038/415536a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu C, Anderson AC, Schubart A, Xiong H, Imitola J, Khoury SJ, et al. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1245–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woo SR, Turnis ME, Goldberg MV, Bankoti J, Selby M, Nirschl CJ, et al. Immune inhibitory molecules LAG-3 and PD-1 synergistically regulate T-cell function to promote tumoral immune escape. Cancer Res. 2012;72:917–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blackburn SD, Shin H, Haining WN, Zou T, Workman CJ, Polley A, et al. Coregulation of CD8+ T cell exhaustion by multiple inhibitory receptors during chronic viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:29–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jin HT, Anderson AC, Tan WG, West EE, Ha SJ, Araki K, et al. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14733–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009731107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang L, Rubinstein R, Lines JL, Wasiuk A, Ahonen C, Guo Y, et al. VISTA, a novel mouse Ig superfamily ligand that negatively regulates T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2011;208:577–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lines JL, Pantazi E, Mak J, Sempere LF, Wang L, O’Connell S, et al. VISTA is an immune checkpoint molecule for human T cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1924–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flies DB, Han X, Higuchi T, Zheng L, Sun J, Ye JJ, et al. Coinhibitory receptor PD-1H preferentially suppresses CD4 T cell-mediated immunity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1966–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI74589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flies DB, Wang S, Xu H, Chen L. Cutting edge: a monoclonal antibody specific for the programmed death-1 homolog prevents graft-versus-host disease in mouse models. J Immunol. 2011;187:1537–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Mercier I, Chen W, Lines JL, Day M, Li J, Sergent P, et al. VISTA regulates the development of protective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1933–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Okudaira K, Hokari R, Tsuzuki Y, Okada Y, Komoto S, Watanabe C, et al. Blockade of B7-H1 or B7-DC induces an anti-tumor effect in a mouse pancreatic cancer model. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:741–9. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sorensen MR, Holst PJ, Steffensen MA, Christensen JP, Thomsen AR. Adenoviral vaccination combined with CD40 stimulation and CTLA-4 blockage can lead to complete tumor regression in a murine melanoma model. Vaccine. 2010;28:6757–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grosso JF, Jure-Kunkel MN. CTLA-4 blockade in tumor models: an overview of preclinical and translational research. Cancer Immun. 2013;13:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahmed MM, Hodge JW, Guha C, Bernhard EJ, Vikram B, Coleman CN. Harnessing the potential of radiation-induced immune modulation for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1:280–4. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inoue H, Tani K. Multimodal immunogenic cancer cell death as a consequence of anticancer cytotoxic treatments. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:39–49. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, Serwatowski P, Barlesi F, Chacko R, et al. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non–small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2046–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weber JS, Kudchadkar RR, Yu B, Gallenstein D, Horak CE, Inzunza HD, et al. Safety, efficacy, and biomarkers of nivolumab with vaccine in ipilimumab-refractory or -naive melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4311–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duraiswamy J, Kaluza KM, Freeman GJ, Coukos G. Dual blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 combined with tumor vaccine effectively restores T-cell rejection function in tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3591–603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hodi FS, Lee SJ, McDermott DF, Rao UNM, Butterfield LH, Tarhini AA, et al. Multicenter, randomized phase II trial of GM-CSF (GM) plus ipilimumab (Ipi) versus Ipi alone in metastatic melanoma: E1608. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl) abstr CRA9007. [Google Scholar]