Abstract

Background

We examined the clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers considered evidenced-based to heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and recommended target dosing in older adults with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Methods

In OPTIMIZE-HF (2003–2004) linked to Medicare (2003–2008), of the 10,570 older (age ≥65, mean, 81 years) adults with HFpEF (EF ≥40%, mean 55%), 8373 had no contraindications to beta-blocker therapy. After excluding 4614 patients receiving pre-admission beta-blockers, the remaining 3759 patients were potentially eligible for new discharge prescriptions for beta-blockers and 1454 received them. We assembled a propensity-matched cohort of 1099 pairs of patients receiving beta-blockers and no beta-blockers, balanced on 115 baseline characteristics. Evidence-based beta-blockers for HFrEF, namely, carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol and their respective guideline-recommended target doses were 50, 200, and 10 mg/day.

Results

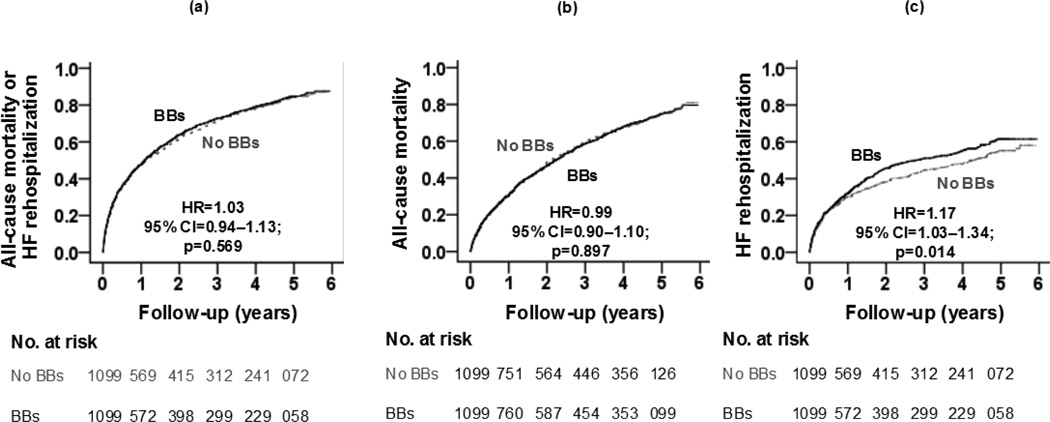

During 6 years of follow-up, new discharge prescriptions for beta-blockers had no association with the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization (hazard ratio, 1.03; 95% confidence interval {CI}, 0.94–1.13; p=0.569). This association did not vary by beta-blocker evidence class or daily dose. Hazard ratios for all-cause mortality and HF rehospitalization were 0.99 (95% CI, 0.90–1.10; p=0.897) and 1.17 (95% CI, 1.03–1.34; p=0.014). The latter association lost significance when higher EF cutoffs of ≥45%, ≥50% and ≥55% were used.

Conclusions

Initiation of therapy with beta-blockers considered evidence-based for HFrEF and in target doses recommended for HFrEF had no association with the composite or individual endpoints of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization in HFpEF.

Keywords: Beta-blockers, heart failure, preserved ejection fraction

1. Introduction

Beta-blockers constitute one of the mainstays of evidence-based therapy for patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [1]. Nearly half of the estimated 6 million HF patients have HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [2]. Findings from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) registry suggest that despite some differences in baseline characteristics, patients with HFpEF are prognostically similar to those with HFrEF [3, 4]. The vast majority of HF patients are ≥65 years, and most of the older HF patients have HFpEF [5]. Yet, they were often excluded from major randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [6]. In the OPTIMIZE-HF, the initiation of beta-blocker therapy had no association with all-cause mortality or all-cause hospital readmission during the first year of follow-up in older HFpEF patients [6]. However, their associations with hospital readmission due to HF, long-term mortality beyond one year, and whether these outcomes varied between beta-blockers considered evidence-based for HFrEF (versus other beta-blockers) and between target doses recommended for HFrEF (versus below-target doses) remain unknown and these important questions are unlikely to be answered by new RCTs. When RCTs are unavailable, impractical, or unethical, propensity score-matched non-RCT studies, which allow outcome-blinded retrospective assembly of balanced cohorts, may provide timely and cost-effective [7–10]. Therefore, in the current study, we examined the association of beta-blocker therapy with long-term outcomes in propensity-matched cohorts of real-world older HFpEF patients, overall, and by their HFrEF evidence class and target doses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Source of data and study patients

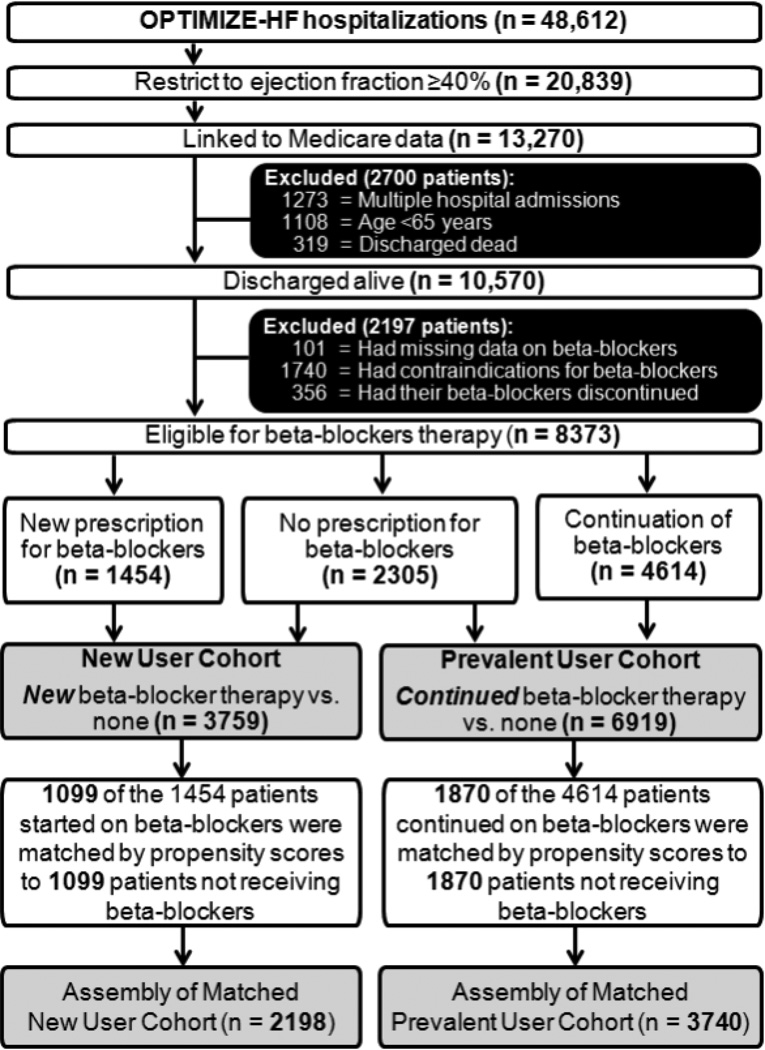

The OPTIMIZE-HF is a United States national registry of hospitalized HF patients and has been well described in the literature [11–13]. Briefly, patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes were eligible for inclusion in OPTIMIZE-HF [14]. Extensive data on baseline demographics, medical history including admission and discharge medications, hospital course, and discharge disposition were abstracted and collected by trained staff from 48,612 charts from 259 hospitals from 48 states between March 2003 and December 2004 [11]. To prevent out-of-range entry or duplicate patients, electronic data checks were done automatically. A random 5% sample of the first 10,000 patients was verified against source documents [13]. Considering that HF patients with EF 40% to 50% are characteristically and prognostically similar to those with EF >50% [4], we used EF ≥40% to define HFpEF. Of the 48,612 hospitalizations, 20,839 were due to HFpEF (EF ≥40%). Because of unavailability of long-term outcomes data in OPTIMIZE-HF, we linked OPTIMIZE-HF to Medicare outcomes data up to December 31, 2008, obtained from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [15]. Of the 20,839 HF hospitalizations due to HFpEF, we were able to link 13,270 to the Medicare data that occurred in 11,997 unique patients, of whom 10,889 were 65 years or older and 10,570 of them were discharged alive (Figure 1) [15].

Figure 1.

Flow chart displaying assembly of matched new user and prevalent user cohorts of patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction

2.2. Data on beta-blocker use

Names, doses and frequency of beta-blockers and for those not receiving these drugs, data on reason for non-use or contraindications were collected. From the 10,570 patients, we excluded 101 patients with missing data on discharge beta-blocker use, 1740 patients with contraindications, and 356 patients whose pre-admission beta-blocker therapy was discontinued prior to hospital discharge. Contraindications included prior allergy, second or third-degree heart block without a pacemaker, symptomatic bradycardia, symptomatic hypotension, cardiogenic shock, or reactive airway disease [16]. The final working sample consisted of 8373 patients who were considered potentially eligible for beta-blocker therapy, of which 2305 (28%) were not prescribed one (Figure 1). Of the 6068 who received a discharge prescription for beta-blockers, 3234 (58%) received beta-blockers considered evidence-based for HFrEF: carvedilol (n=1401), metoprolol succinate (n=1799), and bisoprolol (n=34). Of the non-evidence-based beta-blockers, 1105 received atenolol, 1330 received metoprolol tartrate, and 399 received other beta-blockers. Based on guideline recommended target doses for HFrEF, target doses for evidence-based beta-blockers were defined as follows: 50 mg/day for carvedilol, 200 mg/day for metoprolol succinate, and 10 mg/day for bisoprolol [1, 17]. The dose threshold for 2 non-evidence-based beta-blockers was 200 mg/day for atenolol and 200 mg/day for metoprolol tartrate as previously described [17].

2.3. Assembly of an eligible cohort for initiation of beta-blocker therapy

To minimize selection bias or left truncation associated with prevalent drug use [18–20], we assembled an inception cohort in which those receiving a new prescription of beta-blockers could be compared with those not receiving a discharge prescription. Of the 6068 patients who received beta-blockers during hospital discharge, 4614 were receiving beta-blockers before hospital admission. Thus, 1454 patients received a new discharge prescription for beta-blockers. Taken together with the 2305 who did not receive a beta-blockers, the assembled inception cohort consisted of 3759 patients, of whom 39% (n=1454) received beta-blockers (Figure 1).

2.4. Assembly of balanced study cohorts

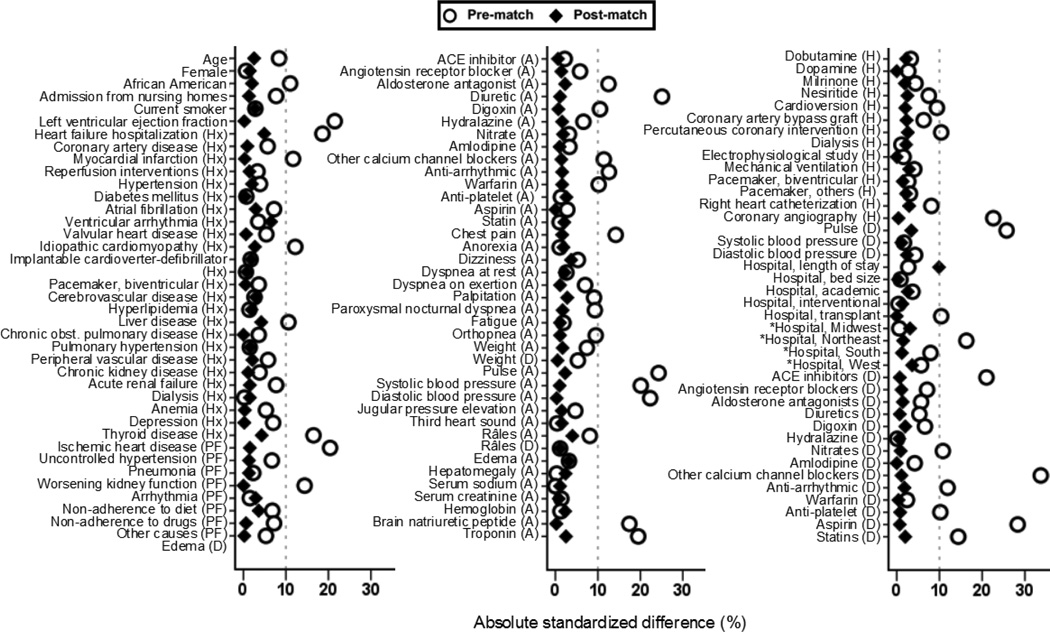

To minimize bias associated with imbalances in the distribution of baseline characteristics between patients receiving and not receiving beta-blockers, we used propensity scores to assemble cohorts that would be balanced on all measured baseline characteristics [7–9, 21]. We estimated propensity scores for the receipt of beta-blockers using non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression models, in which the receipt of beta-blockers was the dependent variable and 115 baseline characteristics displayed in Figure 2 were used as covariates [22, 23]. Using a greedy matching protocol, we were able to match 1099 patients receiving initial beta-blocker therapy with another 1099 patients not receiving these drugs who had similar propensity for their receipt [24, 25]. The effectiveness of propensity score model was assessed by estimating absolute standardized differences, and presented as a Love plot [26]. Absolute standardized difference values <10% are considered inconsequential and 0% indicates no residual bias. We repeated the above process to assemble 2 other matched cohorts: (1) a prevalent-user cohort of 1870 pairs of patients receiving and not receiving a prescription to continue beta-blockers therapy (Figure 1) and (2) an all-user cohort of 2104 pairs of patients receiving or not receiving a prescription for initiation or continuation of beta-blockers during discharge,.

Figure 2.

Love plots displaying absolute standardized differences comparing 115 baseline characteristics between older adults with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction, receiving new discharge prescriptions for beta-blockers (versus none), before and after propensity score matching (Hx=before admission; A=admission; D=discharge; H=during hospitalization; PF=precipitating factor for hospital admission; ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme; *In the propensity score model, the 4 hospital regions were used as a single categorical variable with 4 values)

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization during a median 2.2 years of follow-up (minimum, 0 and maximum, 6 years). Secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality, HF rehospitalization, and all-cause rehospitalization. All outcomes data were obtained from the 100% MedPAR File and 100% Beneficiary Summary File from March 01, 2003 to December 31, 2008 [15]. Medicare-linked OPTIMIZE-HF patients have been shown to be characteristically and prognostically similar to HF patients in the general Medicare population [27].

2.6. Statistical analysis

For descriptive analyses, Pearson’s Chi-square, Wilcoxon rank-sum, McNemar’s, and paired sample t tests were used for pre- and post-match between-group comparisons, as appropriate. To estimate the association of discharge prescriptions for beta-blockers with outcomes, we used Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses. Proportional hazards assumptions were checked using log-minus-log scale survival plots. Formal sensitivity analyses may estimate the degree of hidden bias that could potentially eliminate a significant association among matched patients [28], but was not conducted for reasons explained under the results section. Subgroup analyses were conducted to determine the homogeneity of association between the use of beta-blockers and the composite primary endpoint in the inception cohort. We then compared evidence-based and non-evidence-based beta-blockers to those not receiving beta-blockers, and those receiving at or above target and below-target doses of beta-blockers to those not receiving beta-blockers. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses by replicating the above process and assembling 3 propensity-matched cohorts of HFpEF, using alternative EF cutoffs of ≥45%, ≥50% and ≥55%. All statistical tests were 2-tailed with a p-value <0.05 considered significant. SPSS for Windows version 20 (2011, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used for data analysis.

3. Results

Overall, matched patients in the inception cohort (n=2198) had a mean (±SD) age of 81 (±8) years, mean (±SD) EF of 55 (±10) percent, 65% were women, and 11% were African American. Before matching, those receiving beta-blockers were more likely to be older, have lower EF and have higher prevalence of myocardial infarction, and more likely to receive angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which along with the remaining 115 baseline characteristics were balanced after matching, with absolute standardized differences values <10% (Tables 1 and 2, and Figure 2).

Table 1.

Baseline patient and care characteristics of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), by new discharge prescription of beta-blockers, before and after propensity score matching

| Variables Mean (±SD) or n (%) |

Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | P value | Beta-blockers | P value | |||

| No (n=2305) | Yes (n=1454) | No (n=1099) | Yes (n=1099) | |||

| Age (years) | 80.7 (±8) | 81.3 (±8) | 0.013 | 81.3 (±8) | 81.1 (±8) | 0.558 |

| Female | 1484 (64) | 940 (65) | 0.867 | 714 (65) | 706 (64) | 0.757 |

| African American | 213 (9) | 184 (13) | 0.001 | 124 (11) | 117 (11) | 0.685 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 56 (±9) | 54 (±10) | <0.001 | 55 (±9) | 55 (±10) | 0.971 |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 868 (38) | 588 (40) | 0.088 | 436 (40) | 441 (40) | 0.858 |

| Myocardial infarction | 280 (12) | 236 (16) | <0.001 | 153 (14) | 154 (14) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 1637 (71) | 1058 (73) | 0.247 | 787 (72) | 797 (73) | 0.675 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 850 (37) | 531 (37) | 0.825 | 411 (37) | 413 (38) | 0.964 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 833 (36) | 476 (33) | 0.033 | 394 (36) | 379 (35) | 0.522 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 604 (26) | 398 (27) | 0.430 | 310 (28) | 296 (27) | 0.528 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 686 (30) | 364 (25) | 0.002 | 289 (26) | 269 (25) | 0.352 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 300 (13) | 182 (13) | 0.657 | 135 (12) | 141 (13) | 0.745 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1480 (64) | 893 (61) | 0.084 | 696 (63) | 685 (62) | 0.666 |

| Admission symptoms and signs | ||||||

| Dyspnea on exertion | 1404 (61) | 935 (64) | 0.037 | 685 (62) | 691 (63) | 0.826 |

| Orthopnea | 495 (22) | 371 (26) | 0.004 | 265 (24) | 270 (25) | 0.842 |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea | 250 (11) | 202 (14) | 0.005 | 137 (13) | 131 (12) | 0.748 |

| Dyspnea at rest | 1006 (44) | 616 (42) | 0.441 | 472 (43) | 460 (42) | 0.638 |

| Chest pain | 393 (17) | 330 (23) | <0.001 | 234 (21) | 227 (21) | 0.752 |

| Pulse (beats per minute) | 85 (±20) | 90 (±23) | <0.001 | 88 (±22) | 87 (±21) | 0.996 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 145 (±29) | 151 (±33) | <0.001 | 149 (±29) | 148 (±32) | 0.816 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 73 (±17) | 77 (±20) | <0.001 | 75 (±18) | 75 (±19) | 0.945 |

| Jugular venous pressure elevation | 568 (25) | 388 (27) | 0.161 | 280 (26) | 287 (26) | 0.765 |

| Pulmonary râles | 1442 (63) | 966 (66) | 0.016 | 733 (67) | 712 (65) | 0.369 |

| Lower extremity edema | 1532 (67) | 944 (65) | 0.332 | 704 (64) | 721 (66) | 0.477 |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 136 (±12) | 136 (±11) | 0.989 | 136 (±12) | 136 (±11) | 0.792 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.52 (±1.09) | 1.50 (±1.22) | 0.667 | 1.50 (±1.10) | 1.51 (±1.26) | 0.855 |

| Serum hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12 (±4) | 12 (±3) | 0.734 | 12 (±2) | 12 (±3) | 0.594 |

| Serum brain natriuretic peptide | 819 (±758) | 960 (±860) | <0.001 | 894 (±857) | 896 (±807) | 0.955 |

| Serum troponin elevation* | 298 (13) | 293 (20) | <0.001 | 186 (17) | 176 (16) | 0.605 |

| Discharge symptoms & signs | ||||||

| Pulse (beats per minute) | 77 (±13) | 74 (±13) | <0.001 | 74 (±13) | 75 (±13) | 0.422 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 129 (±21) | 129 (±22) | 0.610 | 129 (±21) | 129 (±21) | 0.980 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 66 (±12) | 66 (±12) | 0.199 | 65 (±12) | 66 (±12) | 0.573 |

| Pulmonary râles | 316 (14) | 194 (13) | 0.749 | 151 (14) | 147 (13) | 0.851 |

| Lower extremity edema | 500 (22) | 284 (20) | 0.112 | 218 (20) | 219 (20) | 1.000 |

| Length of hospital stay | 12 (±304) | 6 (±5) | 0.467 | 6 (±4) | 6 (±5) | <0.001 |

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Bed size | 392 (±250) | 390 (±240) | 0.799 | 388 (±245) | 389 (±241) | 0.939 |

| Academic | 933 (41) | 615 (42) | 0.270 | 451 (41) | 465 (42) | 0.576 |

| Interventional | 1751 (76) | 1102 (76) | 0.903 | 834 (76) | 840 (76) | 0.802 |

| Transplant | 367 (16) | 179 (12) | 0.002 | 144 (13) | 144 (13) | 1.000 |

| Hospital location by region | ||||||

| Midwest | 731 (32) | 465 (32) | <0.001 | 352 (32) | 368 (34) | 0.825 |

| Northeast | 273 (12) | 256 (18) | 161 (15) | 167 (15) | ||

| South | 796 (35) | 448 (31) | 355 (32) | 349 (32) | ||

| West | 505 (22) | 285 (20) | 231 (21) | 215 (20) | ||

Determined by local laboratories.

Table 2.

Treatment and procedure characteristics of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), by new discharge prescription of beta-blockers, before and after propensity score matching

| Variables Mean (±SD) or n (%) |

Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | P value | Beta-blockers | P value | |||

| No (n=2305) | Yes (n=1454) | No (n=1099) | Yes (n=1099) | |||

| Admission medication | ||||||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 707 (31) | 431 (30) | 0.503 | 341 (31) | 344 (31) | 0.927 |

| Angiotensin receptors blockers | 285 (12) | 153 (11) | 0.087 | 126 (12) | 121 (11) | 0.791 |

| Diuretics | 1477 (64) | 753 (52) | <0.001 | 625 (57) | 631 (57) | 0.825 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 102 (4) | 32 (2) | <0.001 | 27 (3) | 31 (3) | 0.694 |

| Digoxin | 459 (20) | 231 (16) | 0.002 | 196 (18) | 199 (18) | 0.908 |

| Hydralazine | 50 (2) | 19 (1) | 0.055 | 16 (2) | 14 (1) | 0.856 |

| Nitrates | 376 (16) | 220 (15) | 0.334 | 169 (15) | 176 (16) | 0.732 |

| Amlodipine | 215 (9) | 122 (8) | 0.327 | 97 (9) | 100 (9) | 0.883 |

| Non-amlodipine calcium channel blockers | 514 (22) | 258 (18) | 0.001 | 201 (18) | 207 (19) | 0.781 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs | 244 (11) | 102 (7) | <0.001 | 98 (9) | 93 (9) | 0.764 |

| Warfarin | 497 (22) | 255 (18) | 0.003 | 217 (20) | 224 (20) | 0.750 |

| Anti-platelet drugs | 218 (10) | 132 (9) | 0.697 | 91 (8) | 99 (9) | 0.598 |

| Aspirin | 775 (34) | 508 (35) | 0.407 | 391 (36) | 391 (36) | 1.000 |

| Statins | 560 (24) | 347 (24) | 0.764 | 281 (26) | 271 (25) | 0.658 |

| In-hospital treatment/procedure | ||||||

| Dobutamine | 29 (1) | 24 (2) | 0.320 | 15 (1) | 18 (2) | 0.728 |

| Dopamine | 42 (4) | 32 (2) | 0.416 | 19 (2) | 19 (2) | 1.000 |

| Milrinone | 4 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | 0.166 | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 1.000 |

| Nesiritide | 130 (6) | 109 (8) | 0.023 | 71 (7) | 78 (7) | 0.614 |

| Right heart catheterization | 45 (2) | 47 (3) | 0.013 | 25 (2) | 30 (3) | 0.583 |

| Coronary angiography | 95 (4) | 143 (10) | <0.001 | 74 (7) | 73 (7) | 1.000 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 9 (0.4) | 13 (0.9) | 0.049 | 6 (0.5) | 8 (0.7) | 0.774 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 14 (1) | 25 (2) | 0.001 | 11 (1) | 14 (1) | 0.690 |

| Electro physiological study | 12 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 0.641 | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Cardioversion | 12 (1) | 21 (1) | 0.003 | 8 (1) | 10 (1) | 0.815 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 42 (2) | 35 (2) | 0.217 | 20 (2) | 16 (2) | 0.618 |

| Pacemaker-biventricular | 12 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) | 0.432 | 4 (0.4) | 5 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Pacemaker-other | 28 (1) | 23 (2) | 0.343 | 18 (2) | 15 (1) | 0.728 |

| Dialysis | 76 (3) | 45 (3) | 0.732 | 29 (3) | 33 (3) | 0.704 |

| Discharge medication | ||||||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 969 (42) | 763 (53) | <0.001 | 532 (48) | 536 (49) | 0.898 |

| Angiotensin receptors blockers | 328 (14) | 172 (12) | 0.035 | 139 (13) | 135 (12) | 0.846 |

| Diuretics | 1884 (82) | 1158 (80) | 0.112 | 896 (82) | 893 (81) | 0.912 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 166 (7) | 127 (9) | 0.088 | 83 (8) | 79 (7) | 0.800 |

| Digoxin | 527 (23) | 293 (20) | 0.050 | 273 (22) | 228 (21) | 0.666 |

| Hydralazine | 60 (3) | 38 (3) | 0.984 | 24 (2) | 25 (2) | 1.000 |

| Nitrates | 457 (20) | 353 (24) | 0.001 | 241 (22) | 245 (22) | 0.882 |

| Amlodipine | 216 (9) | 119 (8) | 0.214 | 99 (9) | 99 (9) | 1.000 |

| Non-amlodipine calcium channel blockers | 526 (23) | 152 (11) | <0.001 | 148 (14) | 144 (13) | 0.843 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs | 287 (13) | 128 (9) | 0.001 | 113 (10) | 107 (10) | 0.725 |

| Warfarin | 555 (24) | 365 (25) | 0.477 | 274 (25) | 276 (25) | 0.960 |

| Anti-platelet drugs | 260 (11) | 214 (15) | 0.002 | 137 (13) | 140 (13) | 0.897 |

| Aspirin | 888 (39) | 763 (53) | <0.001 | 511 (47) | 515 (47) | 0.895 |

| Statins | 547 (24) | 438 (30) | <0.001 | 307 (28) | 297 (27) | 0.665 |

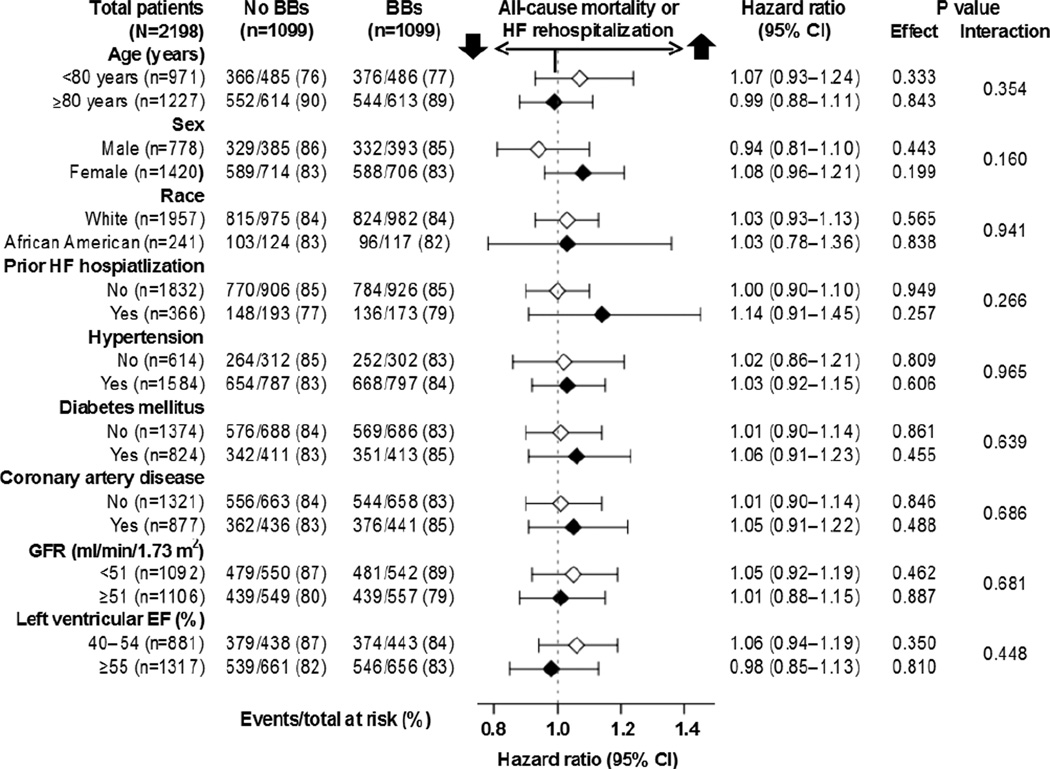

Discharge prescriptions for beta-blockers to older HFpEF patients who were not receiving these drugs prior to admission had no association with the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization during a median of 2.2 years of follow-up, (hazard ratio {HR}, 1.03; 95% confidence interval {CI}, 0.94–1.13; p=0.569; Figure 3 and Table 3). Because this association was not statistically significant, we were not able to perform a formal sensitivity test [28]. This association was homogeneous across various clinically relevant subgroups of HFpEF patients (Figure 4). HRs for all-cause mortality and HF rehospitalization associated with a prescription for initiation of beta-blocker therapy were 0.99 (95% CI, 0.90–1.10; p=0.897) and 1.17 (95% CI, 1.03–1.34; p=0.014), respectively (Figure 3 and Table 3). Similar associations were observed in matched cohorts of HFpEF patients, defined by EF cutoffs ≥45%, ≥50% and ≥55%, except that the association with HF rehospitalization lost significance. HRs for HF rehospitalization for HFpEF patients with EF ≥45%, ≥50% and ≥55% were 1.10 (95% CI, 0.96–1.27; p=0.184), 1.08 (95% CI, 0.92–1.25; p=0.357), and 1.09 (95% CI, 0.92–1.30; p=0.330), respectively.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plot for (a) primary composite endpoint (b) all-cause mortality (c) HF rehospitalization by initiation of beta-blocker (BBs) therapy versus no BBs in a propensity-matched cohort of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HF=heart failure; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval)

Table 3.

Initiation of beta-blocker therapy and post-discharge outcomes in a propensity-matched inception cohort of hospitalized older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), by evidence class and target doses recommended for heart failure and reduced ejection fraction

| Outcomes | Events (%) | Absolute risk difference* |

Hazard ratio† (95% CI) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | |||||

| No | Yes | ||||

| Initiation of beta-blockers, overall | (n=1099) | (n=1099) | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 918 (84%) | 920 (84%) | 0% | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) | 0.569 |

| All-cause mortality | 818 (74%) | 811 (74%) | 0% | 0.99 (0.90–1.10) | 0.897 |

| HF rehospitalization | 435 (40%) | 501 (46%) | +6% | 1.17 (1.03–1.34) | 0.014 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 946 (86%) | 944 (86%) | 0% | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | 0.967 |

| Initiation of beta-blockers, by evidence class | |||||

| Evidence-based‡ | (n=1099) | (n=669) | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 918 (84%) | 559 (84%) | 0% | 1.00 (0.90–1.12) | 0.939 |

| All-cause mortality | 818 (74%) | 497 (74%) | 0% | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.986 |

| HF rehospitalization | 435 (40%) | 303 (45%) | +5% | 1.14 (0.99–1.32) | 0.078 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 946 (86%) | 578 (86%) | 0% | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) | 0.770 |

| Non-evidence-based‡ | (n=1099) | (n=430) | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 918 (84%) | 361 (84%) | 0% | 1.07 (0.94–1.20) | 0.312 |

| All-cause mortality | 818 (74%) | 314 (73%) | −1% | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) | 0.827 |

| HF rehospitalization | 435 (40%) | 198 (46%) | +6% | 1.23 (1.04–1.45) | 0.016 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 946 (86%) | 366 (85%) | −1% | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | 0.768 |

| Initiation of beta-blockers, by recommended target dosages | |||||

| Target dose§ | (n=1099) | (n=162)$ | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 918 (84%) | 128 (79%) | −5% | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | 0.864 |

| All-cause mortality | 818 (74%) | 107 (66%) | −8% | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.177 |

| HF rehospitalization | 435 (40%) | 81 (50%) | +10% | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) | 0.022 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 946 (86%) | 139 (86%) | 0% | 1.07 (0.89–1.28) | 0.475 |

| Below-target dose§ | (n=1099) | (n=871)$ | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 918 (84%) | 738 (85%) | +1% | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) | 0.397 |

| All-cause mortality | 818 (74%) | 657 (75%) | +1% | 1.02 (0.92–1.14) | 0.645 |

| HF rehospitalization | 435 (40%) | 389 (45%) | +5% | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) | 0.046 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 946 (86%) | 753 (87%) | +1% | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.965 |

Absolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percent events in patients not receiving beta-blockers from those receiving those drugs

Hazard ratios comparing patients receiving beta-blockers versus those not receiving those drugs

Evidence-based beta-blockers included bisoprolol, carvedilol or metoprolol succinate; and non-evidence-based BBs included atenolol, metoprolol tartrate and others

Target doses for HFpEF based on recommendations for HFrEF and were defined as follows: atenolol (200 mg/day), bisoprolol (10 mg/day), carvedilol (50 mg/day), metoprolol succinate (200 mg/day), and metoprolol tartrate (200 mg/day)

Based on patients with non-missing data on daily dose

Figure 4.

Association of new discharge prescriptions of beta-blockers (BBs) with primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization in subgroups of propensity-matched inception cohort of older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (CI=confidence interval; EF=ejection fraction; GFR=glomerular filtration rate; HF=heart failure)

HRs (95% CIs) for composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization associated with initiation of evidence-based and non-evidence-based beta-blockers were 1.00 (0.90–1.12; p=0.939) and 1.07 (0.94–1.20; p=0.312), and use of target and below-target doses were 0.98 (0.82–1.18; p=0.864) and 1.04 (0.95–1.15; p=0.397), respectively (Table 3). Corresponding HRs (95% CIs) for other outcomes by class and target dose are displayed in Table 3.

Among matched patients, HR (95% CI) for the composite endpoint associated with prevalent use (continuation only, n=3740) of beta-blocker therapy during hospital discharge was 0.94 (0.87– 1.00; p=0.059; Table 4). Similar association was observed when any use (prevalent or new) was considered (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.88–1.00; p=0.048; Table 4). These associations also did not vary by evidence class or target doses. HRs (95% CIs) for other outcomes are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Continuation or any use (continuation or initiation) of beta-blockers and post-discharge outcomes in propensity-matched cohorts of hospitalized older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)

| Outcomes | Events (%) | Absolute risk difference* |

Hazard ratio† (95% CI) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | |||||

| No | Yes | ||||

| Continuation of beta-blockers | (n=1870) | (n=1870) | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 1585 (85%) | 1542 (83%) | −2% | 0.94 (0.87–1.00) | 0.059 |

| All-cause mortality | 1379 (74%) | 1321 (71%) | −3% | 0.91 (0.84–0.98) | 0.010 |

| HF rehospitalization | 832 (45%) | 817 (44%) | −1% | 0.95 (0.86–1.04) | 0.247 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 1629 (87%) | 1625 (87%) | 0% | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.020 |

| Continuation or initiation of beta-blockers | (n=2104) | (n=2104) | |||

| All-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization | 1775 (84%) | 1723 (82%) | −2% | 0.94 (0.88–1.00) | 0.048 |

| All-cause mortality | 1546 (74%) | 1482 (70%) | −4% | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.011 |

| HF rehospitalization | 897 (43%) | 935 (44%) | +1% | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 0.906 |

| All-cause rehospitalization | 1820 (87%) | 1834 (87%) | 0% | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 0.077 |

Absolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percent events in patients not receiving beta-blockers from those receiving those drugs

Hazard ratios comparing patients receiving beta-blockers versus those not receiving those drugs

4. Discussion

Findings from the current study demonstrate that in a propensity-matched balanced cohort of older HFpEF patients not previously receiving beta-blockers, a new discharge prescription of these drugs had no association with the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization or with the secondary individual endpoints of all-cause mortality, HF rehospitalization, and all-cause rehospitalization. Further, these associations were similar regardless of whether beta-blockers considered evidence-based for HFrEF and in target doses recommended for HFrEF were used. These findings based on nationally representative real-world HFpEF patients and rigorously-conducted propensity-matched studies provide further insights into the role of betablockers in older HFpEF patients.

Despite differences in ventricular remodeling, both HFrEF and HFpEF are associated with similar hemodynamic and neurohormonal changes [29, 30]. Thus, it would seem plausible that beta-blockers, which are beneficial in HFrEF [1], would also improve outcomes in HFpEF. However, angiotensin receptor blockers and to some extent, ACE inhibitors, both beneficial in HFrEF, have failed to improve outcomes in HFpEF [31–33]. Preliminary evidence also points to a similar lack of evidence for aldosterone antagonists in HFpEF [34, 35]. Thus, the lack of evidence of benefits of neurohormonal antagonists in HFpEF most likely points to different pathophysiologic mechanisms from that of HFrEF and that it may not be amenable neurohormonal blockade. In future, mechanistic studies are needed to better understand the pathophysiology of HFpEF and there is an urgent need to develop and test novel interventions that may prevent disease progression and improve outcomes in patients with HFpEF. In addition, most patients with HFpEF are older adults who suffer from multiple comorbid conditions, many non-cardiovascular in nature, which explain the higher rates of non-cardiovascular events in these patients [36–38]. These suggest that improving outcomes in HFpEF may also require interventions that would need to address noncardiovascular comorbidities in real-world older patients with HFpEF [38].

Although the associations between prevalent drug use and outcomes may be biased by confounding due to the left truncation and adjustment of baseline mediators affected by prevalent drug use [18–20], these biases may be inconsequential in regards to the association of prevalent beta-blocker use and lower mortality observed in our study. If beta-blockers reduced mortality in HFpEF, the surviving prevalent users would progressively become more susceptible relative to nonusers and the benefit of the drug would be underestimated [18]. Similarly, if beta-blockers increased mortality, it would lead to a more resilient surviving prevalent users and treatment effect would be overestimated [18]. However, findings from our inception cohort suggest that beta blockers had no intrinsic association with mortality in older HFpEF patients, suggesting lack of evidence for left truncation. Prevalent beta-blocker use may have affected some baseline characteristics such as heart rate and blood pressure and their adjustment could have underestimated a true association, should one exist. The duration of beta-blocker therapy is unlikely to explain the lower mortality observed among prevalent users as no such association was observed during long follow-up of our inception cohort.

The higher HF rehospitalization associated with initiation of beta-blocker therapy while plausible given negative inotropic properties of beta-blockers, is also somewhat counterintuitive given that beta-blockers reduced the risk of HF hospitalization in patients with HFrEF in the RCT setting [1]. Prior studies of neurohormonal antagonists including ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers have not consistently demonstrated reduction in HF hospitalizations in patients with HFpEF [31–33, 39]. Findings from our Kaplan-Meier plots suggest that there was no association between initiation of beta-blocker and HF rehospitalization during the first year of follow-up when nearly half of the events occurred. Finally, our sensitivity analysis using different EF cutoffs to define HFpEF suggest a lack of evidence of higher risk of HF rehospitalization associated with initiation of therapy with beta-blockers.

Most RCTs of beta-blockers in HF excluded older HFpEF patients [1]. In the Study of the Effects of Nebivolol Intervention on Outcomes and Rehospitalisation in Seniors with Heart Failure (SENIOR) trial, nebivolol reduced composite endpoint of total mortality or cardiovascular rehospitalization in older HF patients, but not the individual endpoint components [40]. However, these patients had a mean EF was 36%. A subgroup analysis of SENIOR patients with EF >35% (mean, 47%) suggested similar associations [40, 41]. In a small randomized outcome-blinded trial in 245 patients with HFpEF (EF>40%), carvedilol did not improve outcomes during 3.2 years of median follow-up [42]. Several observational studies have also examined the effect of beta-blockers in HFpEF [43, 44]. However, findings from the current study, taken together with those from the prior report based on OPITIMIZE-HF [6], provide the most comprehensive evidence regarding the association of both incident and prevalent use of beta-blockers with short- and long-term outcomes in older HFpEF patients, overall, and by evidence class and target dose.

Our study has several limitations. We had no data on post-discharge adherence. Substantial crossover during follow-up may result in potential regression dilution and underestimation of true associations [45]. However, findings from ACE inhibitors in HF suggest that the degree of crossover would likely be modest [46], and unlikely to completely nullify true associations. The analyses were restricted to fee-for-service older Medicare patients. However, Medicare-linked OPTIMIZE-HF patients have been shown to be characteristically and prognostically similar to HF patients in the general Medicare population [27]. We did not assess health-related quality of life, functional capacity, or other outcomes that may be of interest. Finally, data for the current analysis were collected from medical records and thus dependent on the accuracy and completeness of clinical documentation.

In conclusion, in real-world hospitalized older patients with HFpEF, we found no evidence that beta-blocker therapy has independent associations with long-term outcomes, regardless of evidence class or daily dosages used.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this manuscript have certified that they comply with the Principles of Ethical publishing in the International Journal of Cardiology.

Funding/Support: The project described was supported by the grant R01-HL097047 from NHLBI/NIH (PI: Ahmed, A). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or NIH. Dr. Ahmed is also supported by a generous gift from Ms. Jean B. Morris of Birmingham, Alabama. Dr. Allman is supported by the UAB CTSA grant (5UL1 RR025777). Dr. Kitzman is supported in part by NIH R37AG18915. OPTIMIZE-HF was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (PI: Fonarow, GC).

Financial Disclosure: G.C.F. has been consultant to Medtronic, Novartis, and Gambro. D.W.K. has received research funding from Novartis, has been consultant for Boston Scientific, Abbott and Relypsa, has been on an advisory board for Relypsa, and has stock ownership (significant) for Gilead and stock options for Relypsa. M.G. has acted as consultant for the following: Abbott Laboratories, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Cardiorentis Ltd, CorThera, Cytokinetics, CytoPherx Inc, DebioPharm SA, Errekappa Terapeutici, GlaxoSmithKline, Ikaria, Intersection Medical Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis Pharma AG, Ono Pharmaceuticals USA, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Palatin Technologies, Pericor Therapeutics, Protein Design Laboratories, Sanofi-Aventis, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Sticares InterACT, Takeda Pharmaceuticals NorthAmerica Inc., and Trevena Therapeutics; and has received significant (US$10 000) support from Bayer Schering Pharma AG, DebioPharm Sa, Medtronic, Novartis Pharma AG, Otsuka pharmaceuticals, Sigma Tau, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Sticares InterACT, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None

All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Contributors

AA, GCF, IBA, TEL conceived the study hypothesis and design, and KP, OJE, GCF, and AA wrote the first draft. AA and KP conducted statistical analyses in collaboration with TEL and IBA. All authors interpreted the data, participated in critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the article. AA, KP and IBA had full access to the data.

References

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:e391–e479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed A, Perry GJ, Fleg JL, Love TE, Goff DC, Jr, Kitzman DW. Outcomes in ambulatory chronic systolic and diastolic heart failure: a propensity score analysis. Am Heart J. 2006;152:956–966. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Gottdiener JS, et al. Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients >or = 65 years of age. CHS Research Group. Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, O'Connor CM, Schulman KA, Curtis LH, Fonarow GC. Clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin DB. Using propensity score to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin PC. Primer on statistical interpretation or methods report card on propensity-score matching in the cardiology literature from 2004 to 2006: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:62–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.790634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michels KB, Braunwald E. Estimating treatment effects from observational data: dissonant and resonant notes from the SYMPHONY trials. JAMA. 2002;287:3130–3132. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2004;148:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kociol RD, Horton JR, Fonarow GC, et al. Admission, discharge, or change in B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term outcomes: data from Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) linked to Medicare claims. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:628–636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.962290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Day of admission and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized for heart failure: findings from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1:50–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.107.748376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;297:61–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Kilgore ML, Arora T, et al. Design and rationale of studies of neurohormonal blockade and outcomes in diastolic heart failure using OPTIMIZE-HF registry linked to Medicare data. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Carvedilol use at discharge in patients hospitalized for heart failure is associated with improved survival: an analysis from Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) Am Heart J. 2007;153:82 e1–82 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heywood JT, Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, et al. Comparison of Medical Therapy Dosing in Outpatients Cared for in Cardiology Practices With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction With and Without Device Therapy Report From IMPROVE HF. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:596–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.912683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danaei G, Tavakkoli M, Hernan MA. Bias in observational studies of prevalent users: lessons for comparative effectiveness research from a meta-analysis of statins. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:250–262. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15:615–625. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinze G, Juni P. An overview of the objectives of and the approaches to propensity score analyses. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1704–1708. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed A, Husain A, Love TE, et al. Heart failure, chronic diuretic, use, increase in mortality and hospitalization: an observational study using propensity score methods. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1431–1439. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filippatos GS, Ahmed MI, Gladden JD, et al. Hyperuricaemia, chronic kidney disease, and outcomes in heart failure: potential mechanistic insights from epidemiological data. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:712–720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed A, Zannad F, Love TE, et al. A propensity-matched study of the association of low serum potassium levels and mortality in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1334–1343. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekundayo OJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Sanders PW, et al. Association between hyperuricemia and incident heart failure among older adults: A propensity-matched study. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed MI, White M, Ekundayo OJ, et al. A history of atrial fibrillation and outcomes in chronic advanced systolic heart failure: a propensity-matched study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2029–2037. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis LH, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, et al. Representativeness of a national heart failure quality-ofcare registry: comparison of OPTIMIZE-HF and non-OPTIMIZE-HF Medicare patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:377–384. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.822692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenbaum PR. Sensitivity to hidden bias. In: Rosenbaum PR, editor. Observational Studies. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. pp. 105–170. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, et al. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA. 2002;288:2144–2150. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee K, Massie B. Systolic and diastolic heart failure: differences and similarities. J Card Fail. 2007;13:569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleland JG, Tendera M, Adamus J, et al. The perindopril in elderly people with chronic heart failure (PEP-CHF) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2338–2345. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, et al. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2456–2467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial. Lancet. 2003;362:777–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, et al. Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:781–791. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel K, Fonarow GC, Kitzman DW, et al. Aldosterone Antagonists and Outcomes in Real-World Older Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart failure. 2013;1:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, et al. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zile MR, Gaasch WH, Anand IS, et al. Mode of death in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction: results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I-Preserve) trial. Circulation. 2010;121:1393–1405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.909614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kitzman DW. Outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: it is more than the heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1006–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel K, Fonarow GC, Kitzman DW, et al. Angiotensin receptor blockers and outcomes in real-world older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a propensity-matched inception cohort clinical effectiveness study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:1179–1188. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flather MD, Shibata MC, Coats AJ, et al. Randomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS) Eur Heart J. 2005;26:215–225. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Veldhuisen DJ, Cohen-Solal A, Bohm M, et al. Beta-blockade with nebivolol in elderly heart failure patients with impaired and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: Data From SENIORS (Study of Effects of Nebivolol Intervention on Outcomes and Rehospitalization in Seniors With Heart Failure) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2150–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamamoto K, Origasa H, Hori M on behalf of the JDHFI. Effects of carvedilol on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Japanese Diastolic Heart Failure Study (J-DHF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:110–118. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I. Effect of propranolol versus no propranolol on total mortality plus nonfatal myocardial infarction in older patients with prior myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and left ventricular ejection fraction >=40% treated with diuretics plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:207–209. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nevzorov R, Porath A, Henkin Y, Kobal SL, Jotkowitz A, Novack V. Effect of beta blocker therapy on survival of patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function following hospitalization with acute decompensated heart failure. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke R, Shipley M, Lewington S, et al. Underestimation of risk associations due to regression dilution in long-term follow-up of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:341–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Butler J, Arbogast PG, Daugherty J, Jain MK, Ray WA, Griffin MR. Outpatient utilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among heart failure patients after hospital discharge. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2036–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]