Abstract

Vascular leiomyoma is a benign, usually solitary tumor arising from the tunica media of the vein. It can occur anywhere in the body wherever smooth muscle is present. These masses are commonly found in the uterus, urogenital tract and gastrointestinal tract but also less commonly in the extremities. They occur more often in the lower extremities than the upper extremities. Females are more affected than males and are generally seen in the third and fourth decades of life.

We present magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathologic features of two pathology proven subcutaneous vascular leiomyomas of the hand and lower leg.

Keywords: Hand, Leg, Leiomyoma, MRI

1. Introduction

Leiomyoma is a benign, slow-growing tumor derived from smooth muscle cells. Leiomyomas are predominantly found in the uterus, esophagus, gastrointestinal system, pleura and lower extremities; wherever smooth muscle is present. It is more common in females than males and is generally seen in the third and fourth decades of life.1,2

Enzinger and Weiss described three types of leiomyoma: vascular, cutaneous and deep soft tissue.3 Vascular leiomyomas originate from the tunica media layer of the vein. Cutaneous leiomyomas are generally intradermal, originate from the non striated muscle of erector pili. Deep soft tissue tumors originate from the vessels and unstriated muscles favoring the lower extremities.4,5 The incidence of the leiomyoma of the lower extremities, particularly the lower leg is 50–70%, and the hand is less than 10%.3,6 In this report, we present two cases of vascular leiomyoma of the hand and the lower leg with magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and histopathologic features.

2. Case report

2.1. Case 1

58 year-old-man was referred to our clinic with one year history of painful, palpable mass on the volar aspect of his right index finger. On the physical examination there was a 2 cm soft, mobile, lobulated mass. Neurological examination was unremarkable. Mass was excised under local anesthesia and closed primarily. There was no local recurrence or sensory deficit at the 4-month follow-up.

Plain radiography demonstrated mild soft tissue swelling without bone involvement or calcification. On the coronal T1WI (Fig. 1), the mass was isointense to muscle. On the axial T2WI (Fig. 2) the mass was non-homogeneous and slightly hyperintense to muscle. There was no fat suppression within the mass (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Coronal T1-weighted MR image (TE: 18, TR:450) of the right 2nd metacarpophalangeal joint shows a homogenous, well-defined mass isointense to muscle.

Fig. 2.

Axial T2-weighted MR image (TE:100, TR:4000) shows, well-defined mass with slightly higher intensity than muscle.

Fig. 3.

Coronal STIR image (TE:30, TR:2800) of the right hand shows a hyperintense smooth, soft tissue mass.

Macroscopically; the mass was solid, encapsulated, and greyish-white on cut surface. Microscopic examination revealed intertwining bundles of smooth-muscle cells without mitotic activity (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for muscle-specific actin and desmin and negative for S-100 and CD-68 (Fig. 5). Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of vascular leiomyoma.

Fig. 4.

Photomicrography of the specimen from leiomyoma shows tumor cells are composed of elongated spindle cells with abundant brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. No evidence of necrosis, pleomorphism, mitosis or nuclear atypia (Hematoxylin–Eosin 100× magnification).

Fig. 5.

Positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin (100×).

2.2. Case 2

36-year-old woman was referred to our clinic with a 1 year history of painful, slow-growing palpable mass in the left posterior lower leg. Physical examination revealed a 1.5 cm tender, hard but mobile mass. The overlying skin was normal. The patient underwent surgical excision under local anesthesia. The mass was easily removed due to non-adherence to the neurovascular structures. Immediately after surgery, the patient had complete relief of pain. There was no local recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Bone radiograph did not reveal any bone abnormality or calcification. Soft tissue sonography demonstrated a well-defined, hypoechoic, non-homogeneous subcutaneous solid lesion. Sagittal T1WI (Fig. 6) revealed a non-homogeneous, well defined subcutaneous mass isointense to muscle. On axial T2WI (Fig. 7), the mass was slightly hyperintense relative to muscle. There was no fat suppression within the mass (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6.

Sagittal T1-weighted MR image (TE:20, TR: 500) shows an oval soft tissue mass in the posterior aspect of the leg, isointense to muscle.

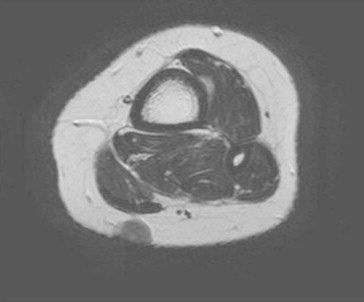

Fig. 7.

Axial T2-weighted MR image (TE:100, TR: 3035) shows slightly hyperintense mass than muscle and multiple hypointense areas of dot-like structures within the mass. That signal voids may be compatible with flow.

Fig. 8.

Coronal STIR image (TE:30, TR:3043) of the left leg shows a hyperintense non-homogeneous soft tissue mass in the subcutaneous tissue.

Macroscopically, the mass was firm and encapsulated with a grayish white cut surface. Microscopic examination revealed intertwining bundles of the smooth-muscle cells without mitotic activity (Fig. 9). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for muscle-specific actin and desmin and was negative for S-100 and CD-68. Histopathological examination confirmed the clinical diagnosis of vascular leiomyoma.

Fig. 9.

Photomicrography of the specimen from leiomyoma of the leg shows the round shaped cells and storiform architecture of spindle cells in the fibrocollagenous stroma. No mitosis was seen (Hematoxylin–Eosin 200× magnification).

3. Discussion

Vascular leiomyoma or angioleiomyoma is a benign smooth muscle tumor arising from the tunica media of the veins.6 Additional postulated site of origins are erector pilli, sweat glands and tunica media of the veins.1,7 They are usually less than 2 cm in the greatest diameter. These lesions can be found in the dermis, subcutaneous fat or deep fascia.6 In physical examination, the tumor is usually a painful and mobile subcutaneous mass.8 Leiomyoma of the lower extremities are more frequent than upper extremities.1,4 Among all the extremity vascular leiomyomas 50–70% are found in the lower extremity and twice as common in females. On the contrary, head, neck and upper extremity lesions are more common in males than females.8 Vascular leiomyomas of the hand are rare, accounting for about 17% of all vascular leiomyomas.9 Etiology is still unknown. In the series reported by Hachisuga et al,10 375 of 562 (66.7%) occurred in the lower extremity, 125 (22.2%) in the upper extremity, 48 (8.6%) on the head and 14 (2.5%)on the trunk. Morimoto et al reviewed the clinicopathology of the vascular leiomyoma and they showed that 70% of 241 cases located below the knee.11 Approximately 80% of extremity leiomyomas were associated with pain, either spontaneously or secondary to touch.1

X-ray findings are usually normal, but, rarely, dystrophic calcifications may be seen. MR imaging is very useful for distinguishing the benign and malignant soft tissue tumors and describing the anatomic borders and vascularity preoperatively. MR findings of leiomyomas are slight hyperintensity to muscle on T1WI, mixed iso/hyperintensity to muscle on T2WI and enhancement after gadolinium injection4 as were shown in our both cases. Leiomyomas typically show no association with neurovascular structures.

Painful subcutaneous extremity lesions such as glomus tumors, hemangiomas, angiolipomas, ganglion cysts and traumatic neuromas should be considered for the differential diagnosis.8 Ganglion cysts and lipomas are benign tumors of the soft tissue, can be reliably differentiated from the leiomyomas with signal intensity characteristics. Ganglions and lipomas are either cystic or fatty masses, respectively. Fibromas tend to show low signal intensity on all pulse sequences.6 Malignant lesions are ill-defined, heterogenous masses and are usually associated with neurovascular structures, such as sarcomas. Soft tissue sarcomas are rarely seen on the hand, and almost always show low to intermediate (isointense to muscle) signal intensity on T1WI. Sarcomas show high signal intensity on T2WI and enhance after contrast injection.12 All of these imaging findings should be considered for the differential diagnosis of the soft tissue tumors. The primary benefit of MR imaging currently is to offer differentiation between benign versus malignant features to help the presurgical evaluation.

Histopathological identification with staining techniques, such as Masson's trichrome, hematoxylin-eosin, alcian blue, van Gieson and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) can be of great value for the diagnosis of the leiomyoma. Also, immunohistochemical stains for vimentin, desmin and smooth muscle actin are adjunct to histopathological identification of leiomyoma.8 Immunohistochemical staining was performed on both of our cases and was positive for both desmin and muscle-specific actin.

Treatment of the leiomyoma is simple excision with ligation of the feeding vessels. However, complexity occurs in cases of close proximity to the neurovascular bundle and the underlying bones. Recurrence is very rare after complete surgical removal.7

In conclusion, angioleiomyomas are rare benign soft tissue tumors presenting with typical but non-specific symptoms. Preoperative MR imaging is crucial to demonstrate the extent of the soft tissue mass and the relationship between the neurovascular structures as well as the underlying bones. Immunohistochemical staining with desmin and muscle-specific actin provide definitive diagnosis.

Conflicts of interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1.Boutayeb F., Ibrahimi A.E., Chraibi F., Znati K. Leiomyoma in an index finger: report of case and review of literature. Hand. 2008;3(3):210–211. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler E., Hamil J., Seipel R., DeLorimier A. Tumors of the hand. A ten-year survey and report of 437 cases. Am J Surg. 1960;100:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(60)90302-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enzinger F.M., Weiss S.W. Benign tumors of smooth muscle. In: Weiss S.W., Goldblum J.R., editors. Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. CV Mosby; St.Louris: 1995. pp. 467–490. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulkarini A.R., Haase S.C., Chung K.C. Leiomyoma of the hand. Hand. 2009;4(2):145–149. doi: 10.1007/s11552-008-9143-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasool M.N., Singh S., Ramdial P.K. Leiomyoma of the calf muscle in a child with calcification and ossification – a case report. SA Orthop J. 2013;12:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang J.W., Ahn J.M., Kang H.S., Suh J.S., Kim S.M., Seo J.W. Vascular leiomyoma of an extremity: MR imaging-pathology correlation. AJR. 1998;171:981–985. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.4.9762979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang W.E., Hsueh S., Chen C.H., Lee Z.L., Chen W.J. Leiomyoma of the hand mimicking a pearl ganglion. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27(2):134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cigna E., Maruccia M., Malzone G., Malpassini F., Soda G., Drudi F.M. A large vascular leiomyoma of the leg. J Ultrasound. 2012;15(2):121–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krandorf M.J. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR. 1995;164(2):395–402. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.2.7839977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hachisuga T., Hashimoto H., Enjoji M. Angioleiomyoma. A clinicopathologic reappraisal of 562 cases. Cancer. 1984;54(1):126–130. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840701)54:1<126::aid-cncr2820540125>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morimoto N. Angiomyoma: a clinicopathologic study. Med J Kagoshima Univ. 1973;24:663–683. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laffan E.E., Ngan B.Y., Navvarro O.M. Pediatric soft-tissue tumors and pseudotumors: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation. Part 2. Tumors of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic, so-called fibrohistiocytic, muscular, lymphomatous, neurogenic, hair matrix, and uncertain origin. Radiographics. 2009;29(4):1–35. doi: 10.1148/rg.e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]