Abstract

Herein, porous nano-silicon has been synthesized via a highly scalable heat scavenger-assisted magnesiothermic reduction of beach sand. This environmentally benign, highly abundant, and low cost SiO2 source allows for production of nano-silicon at the industry level with excellent electrochemical performance as an anode material for Li-ion batteries. The addition of NaCl, as an effective heat scavenger for the highly exothermic magnesium reduction process, promotes the formation of an interconnected 3D network of nano-silicon with a thickness of 8-10 nm. Carbon coated nano-silicon electrodes achieve remarkable electrochemical performance with a capacity of 1024 mAhg−1 at 2 Ag−1 after 1000 cycles.

Silicon is considered the next generation anode material for Li-ion batteries and has already seen applications in several commercial anodes. This is due to its high theoretical capacity of 3572 mAhg−1 corresponding to ambient temperature formation of a Li15Si4 phase1,2. However, silicon has major drawbacks stemming from the large volume expansion upwards of 300% experienced during lithiation3. Depending on the structure, lithiation-induced mechanical stresses cause silicon structures to fracture when the characteristic dimension is as small as 150 nm, which promotes pulverization and loss of active material4,5,6. Despite scaling the dimensions of silicon architectures below this critical dimension, the large volume expansion deteriorates the integrity of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI)7. Expansion upon lithiation and subsequent contraction during delithiation leads to the constant fracturing and reformation of new SEI, resulting in irreversible capacity loss8. Several structures such as double-walled silicon nanotubes, porous silicon nanowires, and postfabrication heat-treated silicon nanoparticle (SiNP) anodes have alleviated this issue via protecting the crucial SEI layer after its initial formation8,9,10.

While a myriad of silicon nanostructures have exhibited excellent electrochemical performance as anode materials, many of them lack scalability due to the high cost of precursors and equipment setups or the inability to produce material at the gram or kilogram level11,12. Silicon nanostructures derived from the pyrolization of silane, such as silicon nanospheres, nanotubes, and nanowires, have all demonstrated excellent electrochemical performance9,11,13. However, chemical vapour deposition (CVD) using highly toxic, expensive, and pyrophoric silane requires costly setups and cannot produce anode material on the industry level14. Metal assisted chemical etching (MACE) of crystalline silicon wafers has been extensively investigated as a means of producing highly tunable silicon nanowires via templated and non-templated approaches15,16. However, electronic grade wafers are relatively costly to produce and the amount of nanowires produced via MACE is on the milligram level17. Crystalline wafers have also been used to produce porous silicon via electrochemical anodization in an HF solution18.

Quartz (SiO2) has been demonstrated as a high capacity anode material without further reduction to silicon, with a reversible capacity of ~800 mAhg−1 over 200 cycles19. However, SiO2 is a wide bandgap insulator with a conductivity ~1011 times lower than that of silicon20. Additionally, SiO2 anodes carry 53.3% by weight oxygen which reduces the gravimetric capacity of the anodes. The highly insulating nature of SiO2 is also detrimental to the rate capability of these anodes21. Tetraethyl Orthosilicate (TEOS) has garnered significant attention recently due its ability to produce nano-SiO2 via hydrolysis22. The SiO2 has been subsequently reduced to silicon in such structures as nanotubes and mesoporous particles11,23. However, examining Fig. 1a reveals the extensive production process needed to produce TEOS. Conversely, Liu et al. have demonstrated a method of synthesizing nano-Si via magnesiothermic reduction of rice husks (SiO2), an abundant by-product of rice production measured in megatons per year24.

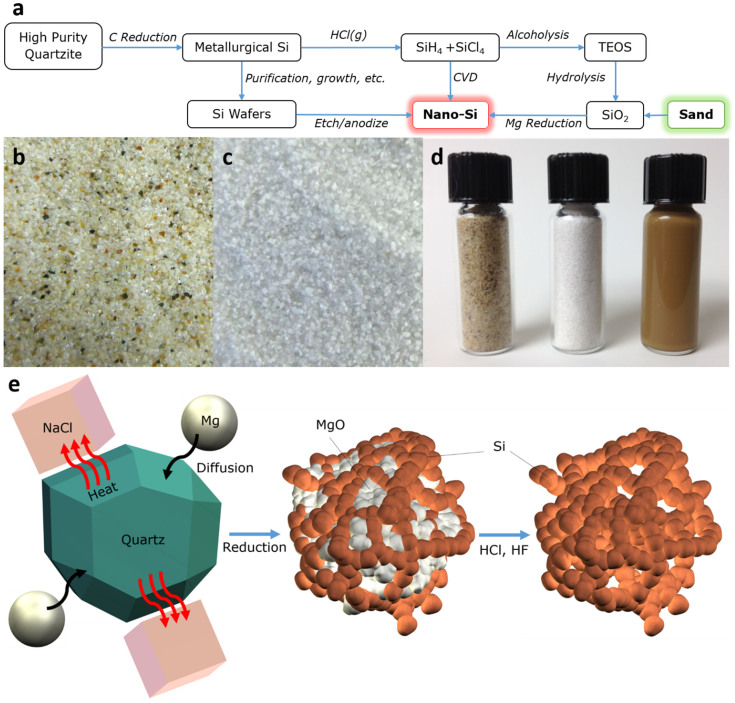

Figure 1.

(a) Flow chart showing conventional synthesis routes of nano-Si, including the introduction of our synthesis route from sand. Optical images of (b) unpurified sand, (c) purified sand, and (d) (from left to right) vials of unpurified sand, purified sand, and nano-Si. (e) Schematic of the heat scavenger-assisted Mg reduction process.

Thermic reduction of SiO2 can be accomplished via a few well-known mechanisms including carbothermal, magnesiothermic, aluminothermic, and calciothermic reduction. Carbothermal reduction utilizes electric arc furnaces operating at >2000°C and is the primary mode for metallurgical silicon production25. However, this process is very energy intensive and liquefies the silicon, thus destroying any original morphology of the SiO2. Recently, magnesiothermic reduction has gained attention due its much lower operating temperatures (~650°C). Typically, Mg powder is placed adjacent to SiO2 powder and the furnace is heated until the Mg vaporizes. However, this reduction scheme produces zonal variations in composition with Mg2Si forming near the Mg powder, Si in the middle, and unreacted SiO2 furthest from the Mg23. Luo et al. have shown that adding a relatively large amount of NaCl to the reduction process aids in scavenging the large amount of heat generated during this highly exothermic reaction. NaCl effectively halts the reaction temperature rise at 801°C during fusion, preventing the reaction from surpassing the melting point of silicon and thus aiding in preserving the original SiO2 morphology26. Herein, we propose a facile and low cost alternative to production of nano-Si with excellent electrochemical performance using a highly abundant, non-toxic, and low cost Si precursor: sand.

Results

The majority constituent of many sands is quartz (SiO2) and sand is easily collected since it is predominantly found on the surface of the earth's crust. The sand used in this analysis was collected from the loamy surface of the shores of Cedar Creek Reservoir in the Claypan region of Texas. The soil of this region is classified as an Alfisol, specifically a Paleustalf, comprising >90% quartz with minor amounts of feldspars and chert27,28. The sand grains utilized herein have a grain size of ~0.10 mm, as in Fig. 1b. Further mechanical milling in an alumina mortar easily reduces the grain size to the micrometer and nanometer scale within minutes. Organic species are removed via calcining in air at 900°C, and the sand is then sequentially washed with HCl, HF, and NaOH for varying amounts of time. Unwanted silicate species are removed via the HF etch, as crystalline quartz etches much slower than other silicate species such as feldspars29. After purification, the sand assumes a bright white appearance in stark contrast to the brown hue of the unpurified sand, as in Fig. 1c. The peaks associated with unpurified sand in the XRD analysis in Fig. 2a confirm that the sample comprises mostly quartz with very minor peaks corresponding to impurities. After purifying the sand, the peaks associated with quartz greatly increase in intensity relative to the impurity peaks, confirming that most of the impurities have been successfully etched away.

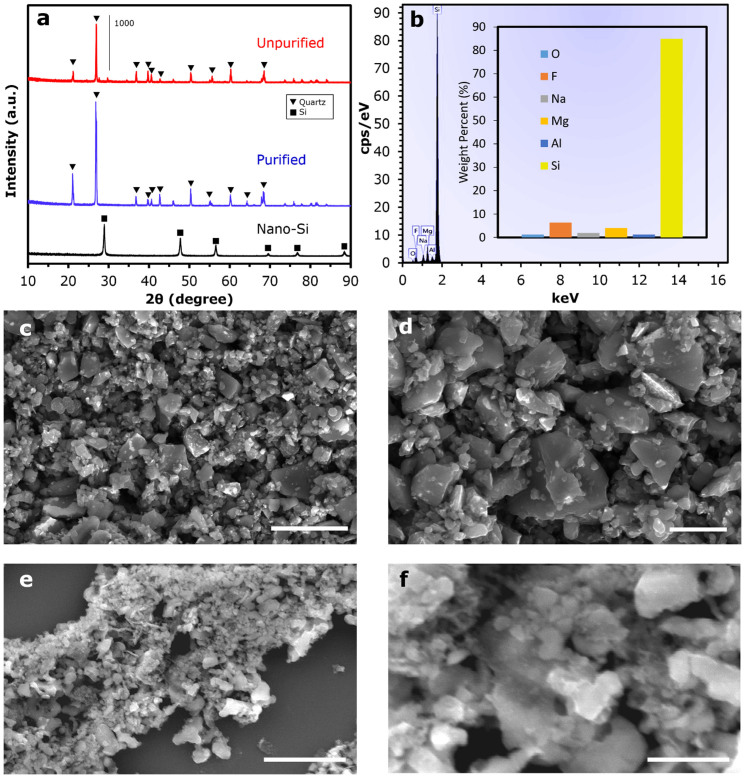

Figure 2.

(a) XRD plot displaying characteristic peaks of quartz in both pre-reduction samples and Si peaks in the post-reduction nano-Si. (b) EDS analysis with inset displaying weight percent of elements in nano-Si after HCl and HF etching. Low magnification (c) and higher magnification (d) SEM images of quartz powder after purification and milling. Low magnification (e) and higher magnification (f) SEM images of nano-Si after reduction and etching. Scale bars for (c),(d), (e), and (f) are 5μm, 2μm, 2μm, and 500 nm, respectively.

After purification, quartz powder and NaCl is ground together in a 1:10 SiO2:NaCl weight ratio and ultrasonicated and vigorously stirred for 2 hours. After drying, the SiO2:NaCl Powder is ground together with Mg powder in a 1:0.9 SiO2:Mg weight ratio. The resultant powder is loaded into Swagelok-type reactors and sealed in an argon-filled (0.09 ppm O2) glovebox. The reactors are immediately loaded into a 1" diameter quartz tube furnace purged with argon. The furnace is slowly heated at 5°Cmin−1 to 700°C and held for 6 hours to ensure complete reduction of all SiO2. After reduction the resulting brown powder is washed with DI water to remove NaCl and then etched with 1 M HCl for 6 hours to remove Mg, Mg2Si, and MgO. The MgCl2 that is produced via HCl etching of MgO can be easily recycled back to Mg via electrolysis, which is the predominant industrial synthesis route for Mg production30. The powder is washed several times with DI H2O and EtOH to remove the etchant and dried overnight under vacuum. A visual comparison, without magnification, of unpurified beach sand, purified quartz, and nano-Si stored in glass vials can be seen in Fig. 1d, and the entire synthesis process can be visualized in Fig. 1e.

SEM imaging in Fig. 2 reveals the broad size distribution and highly irregular morphology of the milled quartz powder before and after reduction. For the milled quartz powder, the particle size ranges from several microns to 50 nm, as in Fig. 2c and 2d. The quartz powder and nano-Si reduction product are both highly irregular in shape as expected. After reduction, the nano-Si is absent of particles with dimensions in excess several microns and has a much smaller size distribution than the quartz powder, as in Fig. 2e and 2f. We can attribute this to the breakdown of relatively larger particles during reduction and ultrasonication, which is due to the reduced mechanical integrity of the porous 3D nano-Si networks in comparison to the solid pre-reduction quartz particles.

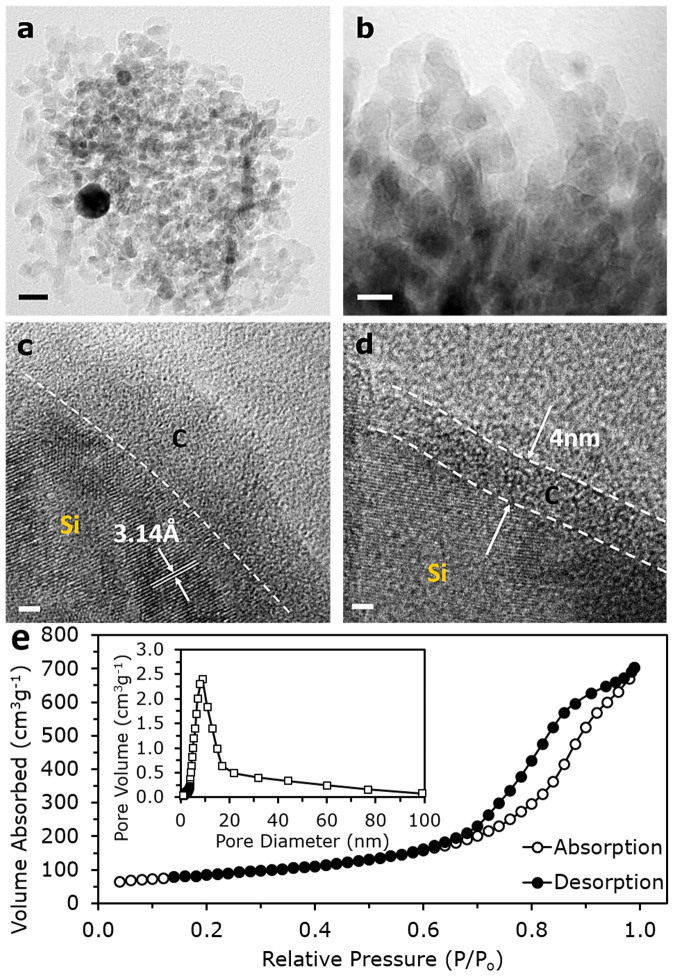

In lieu of the solid crystalline particles found in the quartz powder, the nano-Si powder is composed of a highly porous network of interconnected crystalline silicon nanoparticles (SiNPs). HRTEM in Fig. 3a and 3b reveals the interconnected SiNPs that comprise the 3D Si networks, and the diameter of the SiNPs is ~8–10 nm, with larger particles existing sparingly. This high porosity can be attributed to the selective etching of imbedded MgO and Mg2Si particles after reduction. Through the use a NaCl as a heat scavenger during the reduction process, we are able to synthesize a highly uniform porous structure throughout the width of the particle by avoiding localized melting of Si. This uniform 3D network is achieved via removal of oxygen (53.3% by weight) from the original quartz particles through reduction and a conservation of volume via the heat scavenger (NaCl). The XRD peaks in Fig. 2a indicate a successful reduction to silicon after Mg reduction.

Figure 3.

Low magnification (a) and high magnification (b) TEM images of nano-Si. (c) HRTEM image of nano-Si showing the conformal carbon coating and characteristic lattice spacing of Si(111). (d) HRTEM image of C-coated nano-Si showing thickness of the carbon layer. Scale bars for (a), (b), (c), and (d) are 20 nm, 10 nm, 2 nm, and 2 nm, respectively. (e) BET surface area measurements of nano-Si with type IV N2 sorption isotherms and inset showing pore diameter distribution.

Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) in Fig. 2b reveals the weight percentage of elements present in the nano-Si powder. The quantitative analysis shows Si is the predominant element present with non-negligible amounts of F, Na, Mg, Al, and O. The F and Na peaks may be due to the existence of Na2SiF6, which is produced via a reaction between residual NaCl and H2SiF6 produced during HF etching of SiO2. The existence of Al may be derived from the original sand or from the alumina mortar. While the existence of metallic contaminants at these levels may present deleterious effects for some applications, for battery applications these metallic impurities may increase the conductivity of nano-Si. Despite silicon's relatively high surface diffusion capability with respect to bulk diffusion of Li, silicon has relatively low electrical conductivity31. Thus, nano-Si powders were conformally coated with a ~4 nm amorphous carbon coating to enhance conductivity across all surfaces, as in Fig. 3c and 3d. Briefly, nano-Si powder was loaded into a quartz boat and placed in the center of a quartz tube furnace purged with an H2/Ar mixture. After heating to 950°C, acetylene was introduced into the tube to produce a conformal C-coating. The weight ratio of Si to C was determined to be 81:19 after coating. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area measurements were performed for nano-Si before C-coating yielding a specific surface area of 323 m2g−1, as in Fig. 3e. The inset in Fig. 3e reveals a pore diameter distribution with a peak centred at 9 nm. The pore diameter is in good agreement with the TEM images of porous nano-Si. This high surface area confirms that NaCl effectively scavenges the large amount of heat generated during Mg reduction, preventing agglomeration of nano-Si. The high surface area and pore volume distribution also confirm the existence of large internal porosity available for volume expansion buffering and, thus, minimal capacity fading due to SEI layer degradation and active material pulverization.

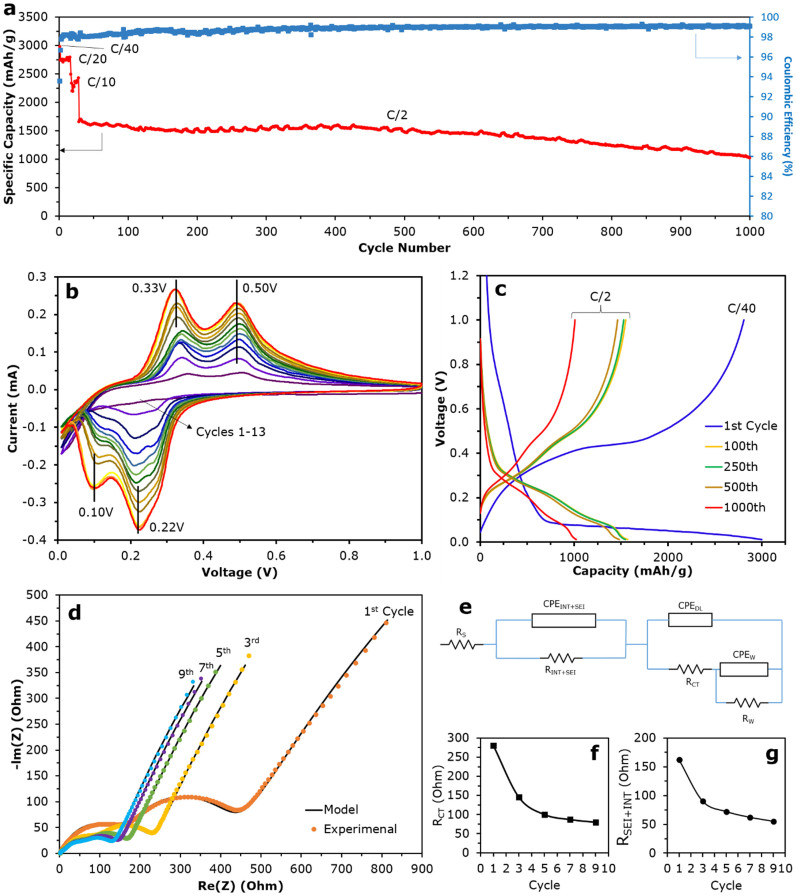

Nano-Si@C derived from sand was electrochemically characterized using the half-cell configuration with Li-metal as the counter-electrode. Electrodes comprised nano-Si@C, acetylene black (AB), and PAA in a 7:1:2 nano-Si@C:AB:PAA weight ratio. Fig. 4a demonstrates the rate capability of the C-coated nano-Si electrodes up to the C/2 rate, with additional cycling up to 1000 cycles at the C/2 rate. Initial cycling at C/40 is necessary for proper activation of all Si and development of a stable SEI layer. This activation process is confirmed via cyclic voltammetry measurements, as in Fig. 4b. The peaks corresponding to the lithiation (0.22 V and 0.10 V) and delithiation (0.33 V and 0.50 V) grow in intensity over the first 12 cycles before stabilizing, which suggests a kinetic enhancement occurs in the electrode. After a kinetic enhancement is achieved via this low current density activation process, the electrodes are cycled at much higher rates. Even at the C/2 rate the nano-Si electrodes demonstrate a reversible capacity of 1024 mAhg−1 and a Coulombic efficiency of 99.1% after 1000 cycles. We attribute the excellent cycle stability of the nano-Si@C electrodes to a combination of the conformal C-coating, PAA binder, and the porous 3D nano-Si network.

Figure 4.

(a) Cycling data of nano-Si@C anodes with selected C-rates (C = 4Ag−1). (b) CV plot of the first 13 cycles using a scan rate of 0.02 mVs−1. (c)Charge-discharge curves for selected cycles. (d) EIS curves for selected cycles showing both experimental and fitted-model data. (e)Equivalent circuit of nano-Si@C electrodes used to produce fitted-model data. Extracted resistance values from the EIS curves for (f) charge transfer resistance and (g) SEI + INT resistance.

The addition of a C-coating alters the makeup of the SEI layer and may also partially alleviate the lithiation-induced volume expansion effects in nano-Si32. The use of PAA as the binder also greatly enhances the cyclability of the electrodes. Magasinski et al. have recently reported on the improved cycling performance of PAA-bound electrodes relative to conventionally used binders such as poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) and carboxymethylcellulose (CMC)33. The improved stability is attributed to PAA's similar mechanical properties to that of CMC but higher concentration of carboxylic functional groups. The mechanical properties of PAA prevent the formation of large void spaces created during lithiation and delithiation of Si. The higher concentrations of carboxylic groups form strong hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups on C and Si, minimizing separation of binder from active material during cycling. The porous nature of the nano-Si is also partly responsible for the good cyclability due to the internal void space available for the interconnected network of Si to expand. Despite the fact that some of the 3D nano-Si networks have diameters of several hundreds of nanometers, the SiNPs that comprise these networks are only 8–10 nm in diameter.

Discussion

Complex impedance plots for nano-Si@C anodes obtained via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) are shown in Fig. 4. The equivalent series resistance (ESR), or high frequency real axis intercept, decreases for the first 5 cycles and stabilizes thereafter. The high frequency semicircle also decreases in diameter with cycling, represented by RSEI + INT. This is the resistance representing the SEI layer and resistance resulting from imperfect contact between current collector and active material. This contact impedance decreases with cycling, as in Fig. 4g. The mid frequency semicircle representing charge transfer impedance decreases sharply for the first 5 cycles, and stabilizes thereafter, as in Fig. 4f. Interfacial impedance remains fairly constant with increasing number of cycles. Therefore, contact impedance among the active particles and the current collector is not affected by cycling. Evidently, the nano-Si@C anodes are not drastically affected by the volume expansion of a typical Si-based anode.

The (EIS) measurements performed after 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 9th cycles show two distinct arcs. The high frequency semicircle corresponds to SEI film and contact impedance while the mid frequency semicircle corresponds to charge transfer impedance on electrode-electrolyte interface34. The Warburg element represents impedance due to diffusion of ions into the active material of the electrode35. The low-frequency (<200 MHz) Warburg impedance tail can be attributed to bulk diffusional effects in nano-Si This includes the diffusion of salt in the electrolyte and lithium in the nano-Si@C electrodes36. We observe that the biggest change occurs in impedance between the 1st and the 5th cycle. The change in impedance hereafter (from 5th cycle to 9th cycle) is relatively less pronounced, confirming that the anode tends to stabilize as it is repeatedly cycled.

The ability to mitigate the volume expansion related effects is due to the ability to produce a highly porous interconnected 3D network of nano-Si. This is achieved via the addition of a relatively large amount or NaCl, which serves to absorb the large amount of heat generated in this highly exothermic Mg reduction, as in Eq. 1.

|

|

Mg reduction evolves a large amount of heat that can cause local melting of Si and, consequently, aggregation of nano-Si particles (Mg (g): ΔH = −586.7 kJ/molSiO2)26. However, by surrounding the milled quartz particles with a large amount of NaCl (ΔHfusion = 28.8 kJ/mol) the heat is used in the fusion of NaCl rather than in the fusion of Si. Additionally, NaCl is a highly abundant, low cost, and environmentally benign salt that can be subsequently recycled for further reductions. We also observe that the addition of NaCl also serves to reduce the presence of Mg2Si, an unwanted product that can result from excess Mg alloying with Si, as in Eq. 2. Etching of this silicide with HCl produces silane, which is a highly toxic and pyrophoric gas. The presence of Mg2Si also reduces the overall yield of the reduction process.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a highly scalable, cheap, and environmentally benign synthesis route for producing nano-Si with outstanding electrochemical performance over 1000 cycles. The outstanding performance of the nano-Si@C electrodes can be attributed to a number of factors including the highly porous interconnected 3D network of nano-Si, the conformal 4 nm C-coating, and the use of PAA as an effective binder for C and Si electrodes. Nano-Si@C electrode fabrication follows conventional slurry-based methods utilized in industry and offers a promising avenue for production of low cost and high-performance Si-based anodes for portable electronics and electric vehicle applications.

Methods

Synthesis of Nano-Si

Collected sand was first calcined at 900°C to burn off organic impurities. The sand was wet etched in 1 M HCl for 1 hour, 49% HF for 24 h, and then alkaline etched in 1 M NaOH. DI water washing was used after each step to remove previous etchant solution. Purified sand was hand-milled in an alumina mortar for several minutes, ultrasonicated for 1 h, and then left to settle for 3 h. Suspended particles in solution were collected and allowed to dry at 110°C under vacuum for 4 h, while larger settled particles were later re-milled. Dried quartz powder was milled in an alumina mortar with NaCl (Fisher, molecular biology grade) in a 1:10 SiO2:NaCl weight ratio. The SiO2:NaCl powder was added to DI water, vigorously stirred and ultrasonicated for 4 h, and then dried overnight at 110°C under vacuum. Dried SiO2:NaCl powder was then milled with −50 mesh Mg powder (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 1:0.9 SiO2:Mg ratio. The resultant powder was loaded into Swagelok-type reactors and sealed in an Ar-filled glovebox. Reactors were immediately loaded into a 1" quartz tube furnace (MTI GSL1600X). The furnace was ramped to 700°C at 5°Cmin−1 and held for 6 h with a 0.472 sccm Ar flow under vacuum. Resultant powders were washed with DI water and EtOH several times to remove NaCl and then etched in 5 M HCl for 12 h to remove Mg2Si and unreacted Mg. Powders were then etched in 10% HF to remove unreacted SiO2, washed several times with DI and EtOH, and then dried.

Preparation of Electrodes

To increase conductivity, nano-Si powder was loaded into a quartz boat and placed in a 1" quartz tube furnace. Under ambient pressure, the system was heated to 950°C in 25 min under a flow of Ar and H2. At 950°C, C2H2 was introduced and kept on for 20 min to produce a 4 nm C-coating. C-coated nano-Si powder was mixed with acetylene black and PAA (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 7:1:2 weight ratio, spread onto copper foils, and dried for 4 h. The mass loading density was 0.5–1.0 mgcm−2.

Electrochemical Characterization

Electrochemical performance of electrodes was characterized vs. Li using CR2032 coin cells with an electrolyte comprising 1 M LiPF6 in ethylene carbonate and diethyl carbonate (EC:DEC = 1:1, v/v) with a 2% vol. vinylene carbonate (VC) additive for improved cycle life. Cells were assembled in an Argon-filled VAC Omni-lab glovebox. All cells were tested vs. Li from 0.01 to 1.0 V using an Arbin BT2000 at varying current densities. Cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements were conducted on a Biologic VMP3 at a scan rate of 0.02 mVs−1.

Author Contributions

Z.F., W.W., M.O. and C.S.O. designed the experiments and wrote the main manuscript. Z.F., W.W., H.H.B., Z.M., K.A. and C.L. worked on materials synthesis, battery fabrication, galvanostatic charge-discharge and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements, and testing at selected C rates. C.S.O. managed the research team. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Iwamura S., Nishihara H. & Kyotani T. Effect of Buffer Size around Nanosilicon Anode Particles for Lithium-ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 6004–6011 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- McDowell M. T., Lee S. W., Nix W. D. & Cui Y. 25th Anniversary Article: Understanding the Lithiation of Silicon and Other Alloying Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 4966–4985 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J. Porous Si anode materials for lithium rechargeable batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 4009–4014 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. H. et al. Size-Dependent Fracture of Silicon Nanoparticles During Lithiation. ACS Nano 6, 1522–1531 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu I., Choi J. W., Cui Y. & Nix W. D. Size-dependent fracture of Si nanowire battery anodes. Jour. Mech. Phys. Solids 59, 1717–1730 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. W., McDowell M. T., Berla L. A., Nix W. D. & Cui Y. Fracture of crystalline silicon nanopillars during electrochemical lithium insertion. PNAS 109, 4080–4085 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J. C. et al. Enhanced lithiation and fracture behavior of silicon mesoscale pillars via atomic layer coatings and geometry design. J. Power Sources 248, 447–456 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. et al. Stable cycling of double-walled silicon nanotube battery anodes through solid-electrolyte interphase control. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 310–315 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge M., Rong J., Fang X. & Zhou C. Porous Doped Silicon Nanowires for Lithium Ion Battery Anode with Long Cycle Life. Nano Lett. 12, 2318–2323 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan F. M., Chabot V., Elsayed A. Xiao X. & Chen Z. W. Engineered Si electrode nanoarchitecture: A scalable treatment for the production of next-generation Li-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 277–283 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J.-K., Kim J., Jung Y. S. & Kang K. Scalable Fabrication of Silicon Nanotubes and their Application to Energy Storage. Adv. Mater. 24, 5452–5456 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N. et al. A Yolk-Shell Design for Stabilized and Scalable Li-Ion Battery Anodes. Nano Lett. 12, 3315–3321 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y. et al. Interconnected Silicon Hollow Nanospheres for Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes with Long Cycle Life. Nano Lett. 11, 2949–2954 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S., Tokuhashi K., Nagai H., Iwasaka M. & Kaise M. Spontaneous ignition limits of silane and phosphine. Combust. Flame 101, 170–174 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Vlad A. et al. Roll up nanowire battery from silicon chips. PNAS 109, 15168–15173 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. et al. Extended Arrays of Vertically Aligned Sub-10 nm Diameter [100] Si Nanowires by Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching. Nano Lett. 8, 3046–3051 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlad A. et al. Roll up nanowire battery from silicon chips. PNAS 109, 15168–15173 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Huang H., Chu K.-L. & Zhuang Y. Anodized Macroporous Silicon Anode for Integration of Li-Ion Batteries on Chips. J. Electron. Mater. 41, 2369 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Chang W.-S. et al. Quartz (SiO2): a new energy storage anode material for Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 6895–6899 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell B. S. An Introduction to Materials Engineering and Science: For Chemical and Materials Engineers. (John Wiler & Sons, Inc., 2004). [Google Scholar]

- Favors Z. J., Wang W., Bay H. H. George A., Ozkan M. & Ozkan C. Stable Cycling of SiO2 Nanotubes as High-Performance Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingsoyr E. & Christy A. A. Effect of reaction variables on the formation of silica particles by hydrolysis of tetraethyl orthosilicate using sodium hydroxide as a basic catalyst. Surf. Colloid Sci. 116, 67–73 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Richman E. K., Kang C. B., Brezesinski T. & Tolbert S. H. Ordered Mesoporous Silicon through Magnesium Reduction of Polymer Templated Silica Thin Films. Nano Lett. 8, 3075–3079 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Huo K., McDowell M. T., Zhao J. & Cui Y. Rice husks as a sustainable source of nanostructured silicon for high performance Li-ion battery anodes. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribov B. G. & Zinov'ev K. V. Preparation of High_purity Silicon for Solar Cells. Inorg. Mater. 39, 653–662 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Luo W. et al. Efficient Fabrication of Nanoporous Si and Si/Ge Enabled by a Heat Scavenger in Magnesiothermic Reactions. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. Vol. 296 (USDA, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. M., Li Y. & Sumner M. E. Handbook of Soil Sciences. 2nd edn, (CRC Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Mauz B. & Lang A. Removal of the feldspar-derived luminescence component from polymineral fine silt samples for optical dating applications: evaluation of chemical treatment protocols and quality control procedures. Ancient TL 22 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kipouros G. J. & Sadoway D. R. The chemistry and electrochemistry of magnesium production. Adv. Molt. Salt Chem. 6, 127–209 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Zhang W., Wan W., Cui Y. & Wang E. Lithium Insertion In Silicon Nanowires: An ab Initio Study. Nano Lett. 10, 3243–3249 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen Y.-C., Chao S.-C., Wu H.-C. & Wu N.-L. Study on Solid-Electrolyte-Interphase of Si and C-Coated Si Electrodes in Lithium Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 156, A95–A102 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Magasinski A. et al. Toward Efficient Binders for Li-ion Battery Si-Based Anodes: Polyacrylic Acid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 3004–3010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. et al. CoMn2O4 spinel hierarchical microspheres assembled with porous nanosheets as stable anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. & al e. TiO2 modified FeS Nanostructures with Enhanced Electrochemical Performance for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 3 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dees D., Gunen E., Abraham D., Jansen A. & Prakash J. Alternating current impedance electrochemical modeling of lithium-ion positive electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, 1409–1417 (2005). [Google Scholar]