Abstract

Genetically engineered mouse models have been generated to recapitulate major signaling pathways deregulated in melanoma. Although these models are invaluable to delineate the relationship between gene mutations and targeted therapeutics, no spontaneously occurring melanomas are available in laboratory mice, which might be used to discover novel disrupted pathways, other than the widely studied MAPK, PI3-AKT and CDK4-INK4A-RB1. We report multiple spontaneously occurring melanomas on the tail of LT.B6 congenic strain, commonly used to study spontaneous ovarian teratomas. We present the evidence of spontaneous mouse melanoma and successful transplantation into 2 out of 2 mice, thereby enabling a complete histopathologic and clinical characterization. The histopathology of LT.B6 melanomas remarkably resembled a human melanoma subtype, pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma (PEM); and their clinical behavior was similar in indolent growth, metastasis to local lymph nodes and lack of liver metastasis. Lung metastasis was unique in the mice. Using qRT-PCR, we detected the expression of two melanocyte specific genes, Tyrp1 and Mitf, in the transplanted primary tumors and nodal metastases but not liver, confirming the histopathology. This mouse model closely resembled a low-grade variant of human melanoma and could provide the opportunity to globally investigate the genetic and epigenetic alterations associated with metastasis.

Keywords: cutaneous melanoma, pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma, mouse model, lymph node, lung, liver, melanoma metastases, tyrosine-related protein 1 and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

To the editor,

The transplantable B16 melanoma model has been used for decades and continues to be used with various degrees of reproducibility in mice (Fidler, 1975). Melanocytic tumors or nevus-like lesions were induced in two stage cutaneous chemical oncogenesis experiments in various inbred strains of mice (Bannasch and Goessner, 1994; Maronpot, 1999; Sundberg et al., 1997). Recently a number of genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) have been generated to recapitulate the major signaling pathways deregulated in human melanoma, namely the RAS-RAF-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, CDK4-INK4A-RB1 and ARF-TP53 pathways (reviewed in (Damsky and Bosenberg, 2010; Walker et al., 2011). These preclinical models have been invaluable to delineate the relationship between causative gene mutations and molecularly targeted therapeutics; however, there are no spontaneously occurring melanocytic tumors in laboratory mice to globally discover other disrupted gene networks. While melanomas are relatively common in humans and domestic animals exposed to sunlight, the scarcity of spontaneous melanomas in laboratory mice might be the result of the mice never being exposed to sunlight or artificial UV radiation under normal husbandry conditions. Herein, we report the finding of a spontaneous, locally invasive, transplantable malignant melanoma that resembles pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma (PEM), formally known as the “animal/equine - type” in humans (Zembowicz et al., 2004).

We found a 172 day-old female LT.B6 “line E” congenic mouse on routine examination to have multiple raised black nodules on the tail (Figure 1a). Histopathology showed diffusely and heavily pigmented dermal tumors with irregular borders consisting of epithelioid and/or spindled melanocytes surrounded by numerous melanophages (Figure 1b-c). These tumor cells infiltrated fascia between collagen bundles in the tail surrounding nerves and small arteries without invasion (Figure 1d-e). We aseptically removed the nodular masses and finely minced them in physiological saline solution and implanted them subcutaneously into small incisions between the scapulae of the dorsal thorax in four 10 week-old histocompatible LT/SvEiJ female mice. Mice were observed weekly and the first signs of tumor growth were observed nearly 12 months post-surgery at the incision site. Of the four implanted mice, two died for unrelated reasons, and the remaining two developed tumors at the injection site; at necropsy, one mouse had a tumor (2.7 × 2.0 × 1.2 cm3) and the second had a tumor (3.4 × 2.6 × 2.0 cm3). Complete necropsies (Silva, 2012) revealed heavily pigmented non-ulcerated dermal nodules 5-15 mm in diameter (Figure 2a). Overall, the transplanted tumors morphologically resembled the original donor neoplasms with the exception of occasional amelanotic whirling nests consisting of spindle cells with oval nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2b-c). There was no detectable mitotic activity or necrosis in the primary melanomas. Regional cervical and popliteal lymph nodes (LNs) were enlarged, pigmented, and histologically effaced by metastatic tumors resembling the primary lesion (Figure 2d). The nodal metastases were both subcapsular and intraparenchymal, similar to the pattern of nodal metastases in melanoma patients (Dadras, 2011). The lungs contained small numbers of widely scattered individual hyperpigmented epithelioid and spindled cells in the interalveolar space, consistent with pulmonary metastases (Figure 2e). Histopathology of liver sections showed scattered melanophages and melanin throughout sinusoids in the liver parenchyma (Figure 2f). The images shown here and additional images are available in color on line on the Mouse Tumor Biology Database (http://tumor.informatics.jax.org/) (Krupke et al., 2008; Naf et al., 2002). Whole (virtual) slide images are available on Skinbase (http://www.pathbase.net/)(Schofield et al., 2010).

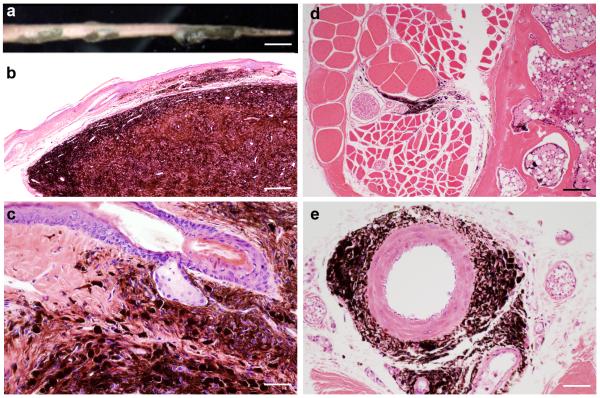

Figure 1.

Clinical and histopathologic features of LT.B6 congenic mouse. Multiple black nodules were noted on the tail of 172 day-old female (a), Bar=7 mm; histologically showing heavily pigmented dermal nodules (b), Bar=200 μm; sparing the adnexae (c), Bar=50 μm; surrounding but not invading the tail nerves (d), Bar=100 μm or the ventral coccygeal artery (e), Bar=50 μm.

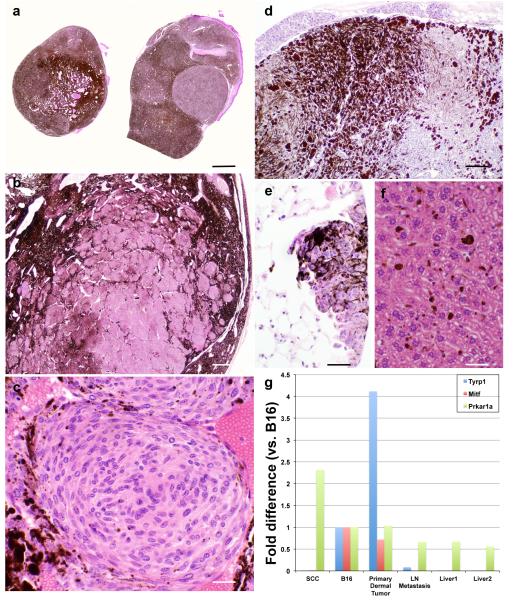

Figure 2.

Histopathology and melanocyte-specific gene expression analysis of transplanted melanomas. Subcutaneously transplanted melanomas grew in the interscapular area of all four mice, giving rise to heavily pigmented dermal nodules (a), Bar=5 mm with amelanotic nests and nodules (b), Bar= 200 μm; showing oval nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (c), Bar=25 μm. After 524 days of transplantation, necropsy showed metastases to the cervical (d), Bar=50 μm and popliteal (not shown) lymph nodes and lungs (e), Bar=25 μm. Only melanin (no tumor cells) was found in the liver sinusoids (f), Bar=25 μm. qRT-PCR showed specific expression of Tyrp1 and Mitf in the B16 melanoma (positive control) and the LT.B6 tumor but not in chemically-induced squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, negative control) (g). Decreased expression of Tyrp1 and Mitf were detected in the metastatic LN but not in two liver samples with sinusoidal melanin. Decreased expression of Prkar1a was detected in LT.B6 and B16 tumors compared to SCC. All reaction assays were performed in triplicate on an ABI 7500 Fast system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) using Sdha as an endogenous control. The qRT-PCR was repeated showing the same results. Cycle threshold (Ct) values for each mRNA were normalized to Sdha (ΔCT) and represented as RQ = 2−ΔCT. For comparison, fold difference of all samples were compared to the B16 melanoma.

To demonstrate melanocyte-specific gene expression, we subjected acid-alcohol fixed paraffin-embedded blocks from the transplanted primary dermal tumors, cervical LN metastasis, two separate liver blocks, chemically induced squamous cell carcinoma (negative control) and B16 transplant (positive control) to quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Total RNA was extracted from the blocks as described (Chakraborty et al., 2013). Using 15 ng total RNA, the quantification of mouse tyrosine-related protein 1 (Tyrp1), microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (Mitf), and protein kinase, cAMP dependent regulatory, type 1, alpha (Prkar1a) and housekeeping gene succinate dehydrogenase complex subunit A (Sdha) transcripts was accomplished by qRT-PCR amplification of a cDNA using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and TaqMan gene expressions assay probes (Life Technologies, USA). The following catalogue numbers represent the respective genes analyzed (Life Technologies, USA): Tyrp1 (Mm00453201_m1), Mitf (Mm00434954_m1), Prkar1a (Mm00660315_m1) and Sdha (Mm01352366_m1). The qRT-PCR results clearly showed that both Tyrp1 and Mitf are expressed in the LT.B6 mouse primary dermal tumor and B16 but not in the SCC (Figure 2g). Lower expression levels of Tyrp1 and Mitf were detected in the LN metastasis but not in either of the liver sections, consistent with tumor metastasis to the LN but not liver. The expressions of Tyrp1 and Mitf were only detected in the melanocytic tumors (B16, primary dermal tumor, and LN metastasis) but not in the SCC or liver sections. The lost expression of Prkar1a has been reported as a molecular event in 28 of PEMs (82%) (Zembowicz et al., 2007). qRT-PCR for Prkar1a showed >2-fold decrease in expression in the primary dermal tumor and LN metastasis, compared to the control (SCC); however, a similar reduction was also detected in B16 tumor (figure 2g).

Historically, the LT strain is light brown (a, Blt) and was developed from a mutation at the brown locus in strain C58 in 1950 and then outcrossed to BALB/c, and commonly used to study spontaneous ovarian teratomas (Damjanov et al., 1975). The LT.B6 “line E” congenic strain was developed to resolve the genetic interval containing the ovarian teratoma susceptibility locus (Ots1) (Lee et al., 1997). Comparing the pathologic features of LT.B6 melanomas to human counterparts showed a remarkable resemblance to the histopathology of PEM (Zembowicz et al., 2004): 1) heavily pigmented dermal tumor without junctional proliferation or epidermal hyperplasia, 2) blue nevus-like architecture, 3) infiltrative borders with extension into subcutaneous tissue along peri-adnexal connective tissue of hair follicles, muscle or neurovascular bundles, 4) dendritic and epithelioid tumor cell cytology and 5) lack of tumor necrosis. We detected no mitoses in LT.B6 melanomas whereas low mitotic activity (1-3/mm2) has been reported for PEM. The biological behavior of LT.B6 melanoma is similar to the clinical behavior of PEM: 1) slow growth, 2) common metastases to regional LNs, 3) rare metastasis to liver; however, lung metastasis in these mice is a different feature than PEM. The finding of a naturally occurring melanoma in the laboratory LT.B6 mouse strain with successful tumor transplantation in 2 out of 2 mice followed by metastases could represent a clinically relevant mouse model for melanoma. Therefore this mouse neoplasm resembles a variant of human melanoma of limited metastatic potential and could provide the opportunity to globally investigate the genetic and epigenetic alterations associated with metastasizing melanoma.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a pilot project grant from a Basic Cancer Center core grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA34196) which also supports The Jackson Laboratory Shared Scientific Services. Electronic images of the lesions are available on the Mouse Tumor Biology Database (R01 CA089713). The authors thank Ms. Elizabeth Fleming (Dadras laboratory) for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Linda Washburn and Eva M. Eicher, Ph.D. for providing the mice with melanoma from their research colony.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Bannasch B, Goessner W. Pathology of Neoplasia and Preneoplasia in Rodents. Vol. 2. Stuttgart; Schattauer: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty NG, Yadav M, Dadras SS, Singh P, Chhabra A, Feinn R, et al. Analyses of T cell-mediated immune response to a human melanoma-associated antigen by the young and the elderly. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:640–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadras SS. Molecular diagnostics in melanoma: current status and perspectives. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:860–9. doi: 10.5858/2009-0623-RAR1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanov I, Katic V, Stevens LC. Ultrastructure of ovarian teratomas in LT mice. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1975;83:261–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00573012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsky WE, Jr., Bosenberg M. Mouse melanoma models and cell lines. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 2010;23:853–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler IJ. Biological behavior of malignant melanoma cells correlated to their survival in vivo. Cancer Research. 1975;35:218–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupke DM, Begley DA, Sundberg JP, Bult CJ, Eppig JT. The Mouse Tumor Biology database. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8:459–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GH, Bugni JM, Obata M, Nishimori H, Ogawa K, Drinkwater NR. Genetic dissection of susceptibility to murine ovarian teratomas that originate from parthenogenetic oocytes. Cancer Research. 1997;57:590–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maronpot R, Boorman GA, Gaul BW. Pathology of the Mouse, Reference and Atlas. Cache River Press; Vienna: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Naf D, Krupke DM, Sundberg JP, Eppig JT, Bult CJ. The Mouse Tumor Biology Database: a public resource for cancer genetics and pathology of the mouse. Cancer Research. 2002;62:1235–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PN, Gruenberger M, Sundberg JP. Pathbase and the MPATH ontology. Community resources for mouse histopathology. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:1016–20. doi: 10.1177/0300985810374845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva K, Sundberg JP. Necropsy methods. In: Hedrich H, editor. The Laboratory Mouse. 2nd ed. Academic Press; London: 2012. pp. 779–806. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg JP, Sundberg BA, Beamer WG. Comparison of chemical carcinogen skin tumor induction efficacy in inbred, mutant, and hybrid strains of mice: morphologic variations of induced tumors and absence of a papillomavirus cocarcinogen. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 1997;20:19–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199709)20:1<19::aid-mc4>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker GJ, Soyer HP, Terzian T, Box NF. Modelling melanoma in mice. Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 2011;24:1158–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zembowicz A, Carney JA, Mihm MC. Pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma: a low-grade melanocytic tumor with metastatic potential indistinguishable from animal-type melanoma and epithelioid blue nevus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:31–40. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zembowicz A, Knoepp SM, Bei T, Stergiopoulos S, Eng C, Mihm MC, et al. Loss of expression of protein kinase a regulatory subunit 1alpha in pigmented epithelioid melanocytoma but not in melanoma or other melanocytic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1764–75. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318057faa7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]