Abstract

Background

Infants with critical congenital heart disease who require cardiothoracic surgical intervention may have significant postoperative mortality and morbidity. Infants who are small for gestational age (SGA) <10th percentile with foetal growth restriction may have end-organ dysfunction that may predispose them to increased morbidity or mortality.

Methods

A single institution retrospective review was performed in 230 infant with congenital heart disease who had cardiothoracic surgical intervention <60 days of age. Pre-, peri-, and post-operative morbidity and mortality markers were collected along with demographics and anthropometric measurements.

Results

There were 230 infants 57 (23.3%) small for gestational age and 173 (70.6%) appropriate for gestational age (AGA). No significant difference was noted in pre-operative markers - gestational age, age at surgery, corrected gestational age, Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery mortality score; or post-operative factors - length of stay, ventilation days, arrhythmias, need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, vocal cord dysfunction, hearing loss; or end-organ dysfunction - gastro-intestinal, renal, central nervous system, or genetic. Small for gestational age infants were more likely to have failed vision tests (p=0.006). Small for gestational age infants were more likely to have increased 30-day (p=0.005) and discharge mortality (p=0.035). Small for gestational age infants with normal birth weight (>2500 grams) were also at increased risk of 30-day mortality compared to AGA infants (p=0.045).

Conclusions

Small for gestational age infants with congenital heart disease who undergo cardiothoracic surgery <60days of age have increased risk of mortality and failed vision screening. Assessment of foetal growth restriction as part of routine preoperative screening may be beneficial.

Keywords: Small for Gestational Age, Critical Congenital Heart Disease, Mortality, Morbidity, Outcome, Fetal Growth Restriction, STS-EACTS Congenital Heart Surgery Mortality Score, Low Birth Weight

Introduction

Congenital heart disease is the most prevalent birth defect affecting 9 in every 1000 live births with 1.35 million newborns diagnosed annually worldwide.1 Today more than 90% of infants with various forms of congenital heart disease will survive to adulthood; although mortality remains greatest in the first year of life. In order to improve the morbidity and mortality associated with congenital heart disease, we need to identify and stratify those at highest risk. In recent studies, low birth weight (LBW, weight <2500 grams) has been identified as a significant preoperative risk factor for mortality in infants with congenital heart disease undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.2,3 An infant’s growth can be stratified and followed longitudinally throughout the pregnancy by estimating the fetal weight by ultrasound or post-natally measuring the birth weight and then classifying an infant as: small for gestational age (weight <10th % for gestational age), appropriate for gestational age (weight >10th and <90th % for gestational age), or large for gestational age (weight >90th % for gestational age). Infants who are small for gestational age may have a constitutional reduction in their growth or may have intrauterine growth restriction due to a pathological process (environmental, maternal heath, placental abnormality or a primary etiology with the fetus). Limitation of fetal growth may affect developmental pathways within the cardiovascular system or other organs, which can have life-long affects to an individual. The heart usually completes it development by the 7th week of gestation and all forms of congenital heart disease have their origins within this time frame. As the pregnancy progresses the heart and vascular system continue to grow along with the fetus. An abnormal fetal environment may cause alterations to the fetal DNA (post processing modifications of histone proteins or methylation patterns) that may lead to changes in all fetal organs. End-organ modification within the systemic vasculature, kidney, pancreas and endocrine system may predispose small for gestation infants to many chronic diseases such as: systemic hypertension, type 2 diabetes (insulin resistance), obesity, and endothelial dysfunction. Infants with congenital heart disease are 1.8 to 3.6 times more likely to experience fetal growth restriction and be small for gestational age.3 We performed a retrospective study to evaluate the mortality and morbidity associated with small for gestational age infants with critical congenital heart disease who required cardiothoracic surgery.

Methods

After institutional review board approval, a single institution retrospective review was performed of all patients under two months of age who underwent surgical repair or palliation of their congenital heart disease at All Children’s Hospital from January of 2007 to December of 201. Data was collected from the CardioAccess Database and the electronic medical record. Patients excluded from the study included infants born large for gestational age and infants undergoing patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) ligation as their primary cardiothoracic procedure. Large for gestational age infants were excluded to avoid any confounding bias from gestational diabetes. Size for gestational age was determined using anthropometric data obtained at birth and weight for gestational age growth curves.5

Preoperative data was composed of patient demographics, anthropometric measurements, cardiac anatomy, documentation of genetic disorders and/or metabolic abnormalities from chromosomal analysis or infant metabolic screens, pre-operative cranial ultrasounds, and pre-operative renal ultrasounds. All patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery at All Children’s Hospital received preoperative screening including: echocardiography, genetic screening and renal/cranial ultrasonography.

Perioperative data included day of life at time of surgery, corrected gestational age at time of surgery, weight at time of surgery, use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), primary and secondary procedures performed, perfusion time, cross clamp time, need for delayed sternal closure, need for dialysis, need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and vocal cord injury. Postoperative data appraised were the duration of hospitalization, duration of ventilatory support,, abnormal hearing screening, abnormal vision screening, and need for gastrostomy tube placement. Abnormal renal ultrasound or cranial imaging were considered positive if there were postoperative changes from preoperative baseline that required additional follow up imaging or subspecialty supervision/care. Ventilatory support was distinguished by total number of days on mechanical ventilation. In-hospital mortality was recorded at two intervals: 30 days postoperatively and at the time of discharge home or death.

Surgical procedures were further stratified based on their relative risk of in-hospital mortality using the Society for Thoracic Surgeons and European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery (STS-EACTS) congenital heart surgery categories.6 Procedures were partitioned into categories labeled 1 to 5, with higher numbered categories implying greater in-hospital mortality risk. If multiple procedures were performed, the surgery bearing the highest associated risk score and category was chosen for stratification.

Descriptive statistics are reported as counts (percentages) for categorical variables and mean (with standard deviation (SD)) or median (range). Comparison between groups was performed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. We estimated unadjusted and adjusted (for gender) odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for outcomes in the SGA and AGA groups. Receiver operating curve (ROC) analyses, computing the area under the curve (AUC) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), were performed to compare the performance of small for gestational age to low birth weight in predicting postoperative mortality. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 and all statistical tests were two-sided with the threshold for significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Demographics/Anthropometrics

A total of 245 patients had critical congenital heart disease and underwent a cardiothoracic surgical procedure within the timeframe of the study. Of those, 15 were identified as large for gestational age and subsequently excluded from weight for gestational age analysis. Table 1 shows the demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the infants included in the study. Of the 230 patients included, 57 (23.3%) were small for gestational age and 173 (70.6%) were appropriate for gestational age. The mean gestational age at birth and at the time of surgery was similar in both groups: 37.1 +/− 2.6 weeks and 39.6+/−3.2 weeks for the small for gestational age; 37.9 weeks +/− 1.8 weeks and 40 weeks +/− 2.7 weeks for the appropriate for gestational age group (p=0.06 and 0.32). The median day of life at time of surgery was also similar 11 days for small for gestational age and 8 for appropriate for gestational age (p=0.15). The mean birth weight for small for gestational age infants was 2.24 kg +/− 0.5 kg and was significantly less than that for appropriate for gestational age 3.11 kg +/− 0.46 kg (p<0.001). Mean weight at time of surgery was also significantly different 2.509 kg +/− 0.48 kg for small for gestational age and 3.291 kg +/− 0.64 kg for appropriate for gestational age infants (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Preoperative Demographics and Anthropometric Measurements for a Cohort of 230 Patients Undergoing Cardiothoracic Surgery for Congenital Heart Disease Less Than 60 Days of Age.

| SGA, n=57 | AGA, n=173 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.018 | ||

| Male, n (%) | 22(38.6%) | 98(56.7%) | |

| Female, n (%) | 35(61.4%) | 75(43.3%) | |

| GA at birth (weeks), mean (sd) | 37.1(2.6) | 37.9(1.8) | 0.06 |

| GA at surgery (weeks), mean (sd) | 39.6(3.2) | 40(2.7) | 0.32 |

| DOL on Surgery, median (range) | 11 (1–60) | 8(1–60) | 0.15 |

| Birth Weight (kg), mean (sd) | 2.24(0.5) | 3.11(0.46) | <0.001 |

| Weight at Surgery (kg), mean (sd) | 2.51(0.48) | 3.29(0.64) | <0.001 |

SGA = Small for gestational age, AGA = Appropriate for gestational age, GA = gestational age, DOL = Day of life, KG = kilograms, SD = standard deviation

Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery In-Hospital Mortality Classification

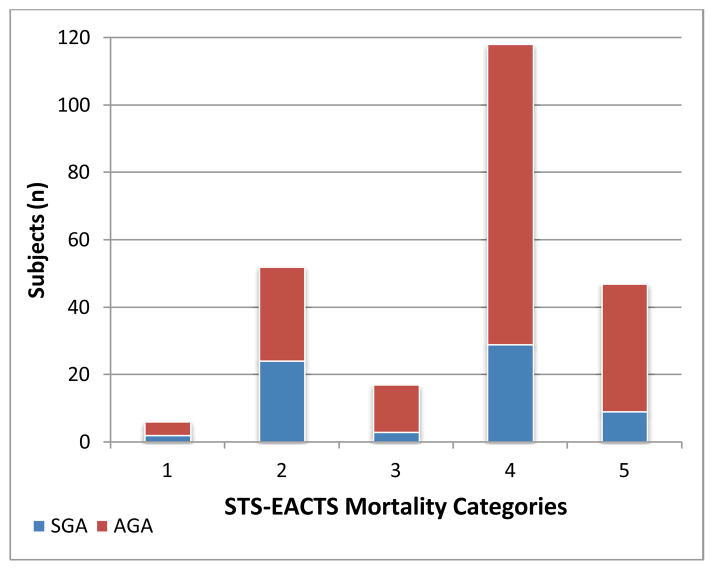

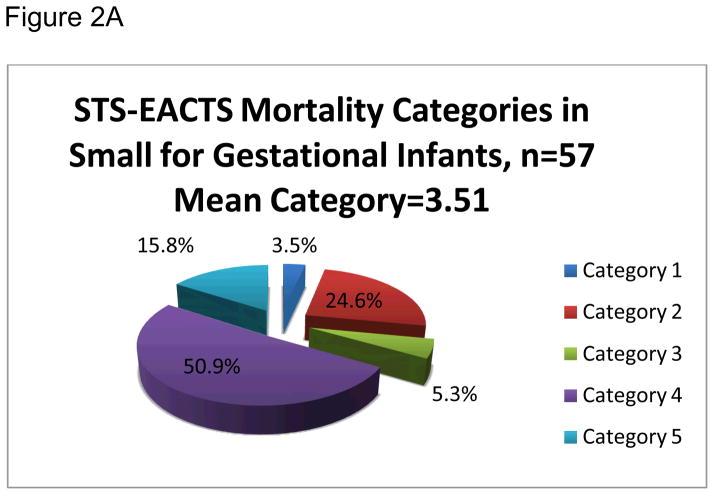

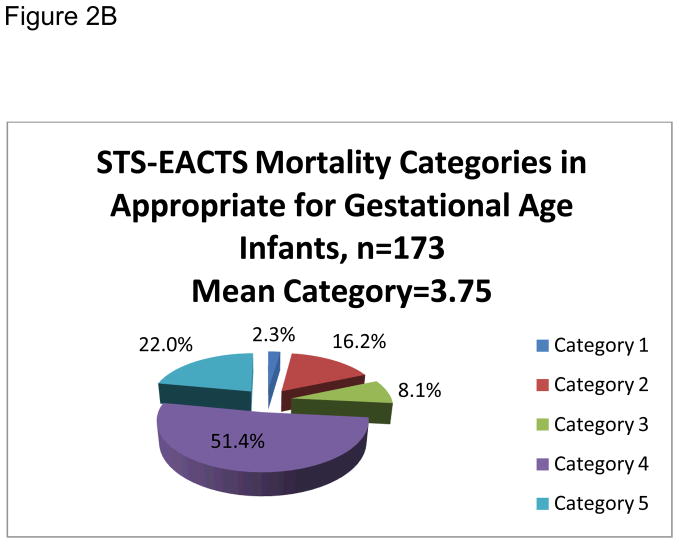

Primary procedures were organized by Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery mortality categories and are shown in detail in Table 2. The mean Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery mortality category was 3.65. The majority of the primary procedures, 71.7%, were classified as either category 4 or 5 (see Figure 1). The small for gestational age and appropriate for gestational age infants had similar complexity and risk in their scheduled cardiac procedures with mean Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery mortality category for the small for gestational age group at 3.51 and 3.75 for appropriate for gestational age, (p=0.21). Equivalent distributions of small for gestational age and appropriate for gestational age infants were organized into the Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery mortality categories (see Figures 2a and 2b).

Table 2.

Procedures Stratified by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons – European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgeons (STS-EACTS) Mortality Category.

| STS-EACTS Category 1 |

2 patients – Tetralogy of Fallot repair, ventriculotomy, nontransannular patch |

| 1 patient – Atrioventricular septal defect repair, intermediate (transitional) | |

| 1 patient – Ventricular septal defect repair, patch, type 2 | |

| 1 patient – Coarctation repair, end to end anastomosis | |

| 1 patient – Vascular ring repair | |

|

| |

| STS-EACTS Category 2 |

22 patients – Coarctation repair, extended end-to-end anastamosis |

| 4 patients – Tetralogy of Fallot repair, ventriculotomy, transannular patch, non-valved | |

| 3 patients – Pacemaker implantation | |

| 3 patients – Patent ductus arteriosus closure + ventricular septal defect repair, patch, type 2 | |

| 2 patients – Coronary anomaly, anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery repair | |

| 2 patients – Right ventricular outflow tract procedure | |

| 1 patient – Patent ductus arteriosus closure + coarctation repair, end to end anastamosis | |

| 1 patient – Pulmonary valvuloplasty | |

| 1 patient – Cor triatriatum repair | |

| 1 patient – Aortopexy | |

| 1 patient – Pericardial reconstruction | |

| 1 patient – Aorto-pulmonary window repair | |

|

| |

| STS-EACTS Category 3 |

14 patients – Aortic switch operation |

| 2 patient – Coarctation and ventricular septal defect repair | |

| 1 patient – Conduit placement, right ventricle to pulmonary artery | |

|

| |

| STS-EACTS Category 4 |

33 patients – Shunt, systemic to pulmonary, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt |

| 10 patients – Truncus arteriosus repair | |

| 11 patients – Pulmonary artery banding | |

| 8 patients – Heart transplant, orthotopic allograft | |

| 8 patients – Interrupted aortic arch repair | |

| 7 patients – Total anomalous pulmonary venous return repair | |

| 7 patients – Aortic arch and ventricular septal defect repair | |

| 6 patients – Arterial switch procedure and ventricular septal defect repair | |

| 6 patients – Aortic arch repair | |

| 6 patients – Shunt, systemic to pulmonary, central (from aorta or to main PA) | |

| 4 patients – Atrial septal defect enlargement | |

| 3 patients – Arterial switch operation, aortic arch and ventricular septal defect repair | |

| 3 patients – Double outlet right ventricle, intraventricular tunnel repair | |

| 2 patients – Ebstein’s anomaly repair | |

| 2 patient – Pulmonary venous stenosis repair | |

| 1 patient – Hypoplastic left heart syndrome, biventricular repair | |

| 1 patient – Cardiac tumor resection | |

|

| |

| STS-EACTS Category 5 |

47 patients – Norwood procedure |

Figure 1.

Society of Thoracic Surgeons – European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgeons (STS-EACTS) Mortality Category Classification for Cohort of 230 Infants, 173 Appropriate for Age (AGA) and 57 Small for Gestational Age (SGA), with Congenital Heart Disease who Underwent Cardiothoracic Surgery Under 60 Days of Life.

Figure 2.

Figures 2A. Society of Thoracic Surgeons – European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgeons (STS-EACTS) Mortality Categories for Small for gestational age (SGA) Infants.

Figures 2B. Society of Thoracic Surgeons – European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgeons (STS-EACTS) Mortality Categories for Appropriate for Gestational Age (AGA) Infants.

Size for Gestational Age Mortality Analysis

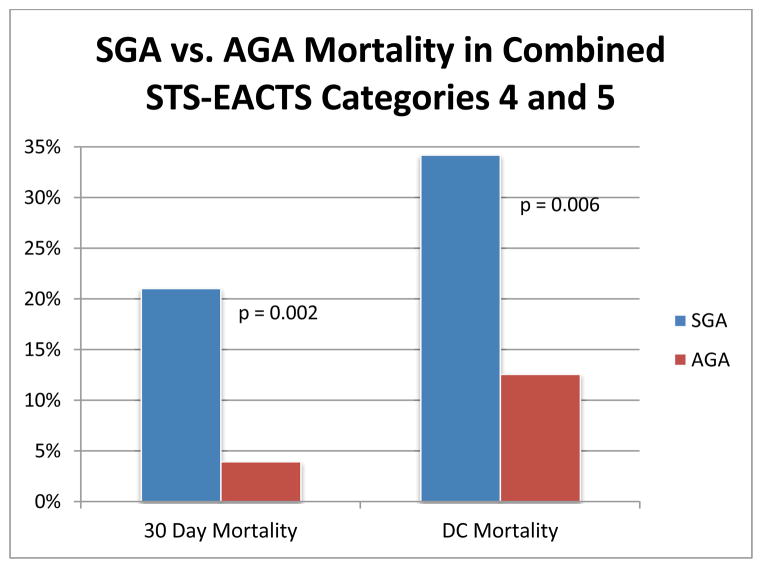

Compared to appropriate for gestational age, the small for gestational age cohort had a statistically significant difference in 30 day mortality (14% vs 3.5%, p=0.005) and discharge mortality (21.1% vs 9.8%, p=0.035), see Table 3. This analysis was adjusted for gender and also revealed that small for gestational age infants had a significant increased risk of 30 day (OR=5.00, 95%CI=1.61–15.52, p=0.005) and discharge (OR=2.43, 95%CI=1.07–5.53, p=0.035) mortality, see Table 4. We also assessed the cumulative mortality in the most complex surgical procedures (categories 4 and 5) and compared small for gestational age to appropriate for gestational age infants. The small for gestational age cohort had significantly higher 30 day and discharge mortality than the appropriate for gestational age group for these complex procedures (21.1% vs 3.9% at 30 days, p=0.0006 and 29% vs 12.6% at discharge, p=0.009). These findings are represented in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Mortality Data at 30 Days and Discharge for Infants Undergoing Cardiothoracic Surgery Under 60 Days of Life by Size for Gestational Age and Birth Weight.

| Mortality | SGA ANALYSIS | LBW ANALYSIS | SGA-NBW ANALYSIS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGA, n=57 | AGA, n=173 | LBW, n=49 | NBW, n=181 | SGA-NBW, n=20 | AGA-NBW, n=161 | |

| 30 Days | 8(14%) | 6(3.5%) | 6(12.2%) | 8(4.4%) | 3(15.0%) | 5(3.1%) |

| p-value = 0.005 | p-value = 0.04 | p-value = 0.045 | ||||

| Discharge | 12(21.1%) | 17(9.8%) | 11(22.45%) | 18(9.9%) | 4(20%) | 14(8.7%) |

| p-value = 0.0345 | p-value = 0.026 | p-value = 0.12 | ||||

SGA = Small for gestational age, AGA = appropriate for gestational age, LBW = low birth weight, NBW = normal birth weight, SGA-NBW = small for gestational age and normal birth weight, AGA-NBW = appropriate for gestational age and normal birth weight.

Table 4.

Pre-operative Findings from Screening Renal Ultrasound, Cranial Ultrasound, and Chromosomal analysis in a Cohort of 230 Infants with Critical Congenital Heart Disease who Underwent Surgical Repair or Palliation.

| RENAL COMORBIDITIES | Pelvocaliectasis, Cysts |

| Adrenal Hemorrhage | |

| CRANIAL/BRAIN COMORBIDITIES | Hemorrhage: Germinal Matrix, Intraventricular, Subarachnoid |

| Periventricular Leukomalacia | |

| GENETIC AND METABOLIC COMORBIDITIES | Metabolic Screening: Biotinidase Deficiency, Inorganic/Organic Acidemia, Congenital Hypothyroidism, Cystic Fibrosis (Carrier State), Carnitine Deficiency |

| Syndromes: Complete & Partial DiGeorge Syndrome, Trisomy 21, Trisomy 13, Turner Syndrome 45XO, Jacobsen Syndrome, Shone Syndrome, Kleefstra Syndrome (9q34.3), Oral-Facial-Digital Syndrome, Heterotaxy, Klinefelter Syndrome and Various Chromosomal Microdeletions and Gain Mutations | |

| Hemoglobinopathy & Coagulopathy: Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutations, Factor V Leidin Deficiency, Sickle Cell Disease (Carrier State) |

Figure 3.

Thirty- day and Discharge (DC) Mortality for Combined Society of Thoracic Surgeons – European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgeons (STS-EACTS) Mortality Categories 4 and 5 in Small for Gestational Age (SGA) and Appropriate for Gestational Age (AGA) Infants.

Low Birth Weight

Of the 230 patients originally identified for investigation, 49 were identified as low birth weight and 181 were normal birth weight (>2500 grams). Infants born with a low birth weight had a 30 day postoperative mortality of 12.2% and discharge mortality of 22.5%. Alternatively, the 181 with a normal birth weight had a 30 day postoperative mortality of 4.4 % and discharge mortality of 9.9%. These data were statistically significant at both time intervals with p-values of 0.04 and 0.026, respectively (see Table 3).

Small for Gestational Age with Normal Birth Weight

We also analyzed small for gestational age infants who had a birth weight >2500 grams compared to appropriate for gestational age with a birth weight >2500 grams. There were 20 small for gestational age normal birth weight infants with a 30 day mortality of 15.0% and discharge mortality of 20.0%; compared to 161 appropriate for gestational age normal weight infants with a 30 day mortality of 3.1% and discharge mortality of 8.7% (p=0.045 at 30 days and p=0.12 at discharge). Statistical significance was not achieved for discharge mortality but the small sample size may have limited the analysis. (see Table 3).

Pre-, Peri- and Post-Operative Comorbidities

At our institution, all pre-operative patients receive a screening chromosomal analysis, renal ultrasound and cranial ultrasound. We compared these parameters between small for gestational age as compared to appropriate gestational age infants and did not observe any statistical difference (genetic abnormality p=0.64, abnormal renal ultrasound p=0.81, and abnormal cranial ultrasound). Table 4 summarizes the abnormal pre-operative screening findings from these three modalities. In addition, perioperative morbidities between the two cohorts did not show any statistical difference for the following categories: need for cardio-pulmonary bypass (p=0.64), perfusion time (p=0.51), cross clamp time (p=0.06), need for delayed sternal closure (p=0.46), need for dialysis (0.81), need for extracorpeal membrane oxygenation (p=0.28), cardiac arrhythmia (p=0.18), seizure activity (p=0.50), and vocal cord injury (p=0.87). Post-operative morbidities were also assessed and small for gestational age infants were more likely to have failed vision screens as compared to appropriate gestational age infants (p=0.005). No differences were seen for length of stay (p=23), length of ventilation (p=0.33), need for a gastrostomy tube (p=0.71), and failed hearing screen (p=0.12). Please see Table 5 for a summary of the morbidity data.

Table 5.

Post-operative Comorbidities in a 230 Patients with Critical Congenital Heart Disease who Underwent Cardiothoracic Surgery Prior to 60 Days of Life.

| AGA1 | SGA2 | unadjusted | sex adjusted | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | n | % | n | % | OR3 | 95% LCL4 | 95% UCL5 | P | OR3 | 95% LCL4 | 95% UCL5 | P |

| 30 day | ||||||||||||

| No | 167 | 96.5 | 49 | 86 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 3.5 | 8 | 14 | 4.54 | 1.51 | 13.73 | 0.007 | 5.00 | 1.61 | 15.52 | 0.005 |

| Discharge | ||||||||||||

| No | 156 | 90.2 | 45 | 79.0 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 17 | 9.8 | 12 | 21.1 | 2.45 | 1.09 | 5.50 | 0.03 | 2.43 | 1.07 | 5.53 | 0.035 |

| Morbidity | ||||||||||||

| Pre-Operative | ||||||||||||

| Genetic Abnormality | ||||||||||||

| No | 131 | 75.7 | 41 | 71.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 42 | 24.3 | 16 | 28.1 | 1.22 | 0.62 | 2.39 | 0.57 | 1.18 | 0.60 | 2.33 | 0.64 |

| Abnormal Renal Ultrasound | ||||||||||||

| Normal | 168 | 97.1 | 56 | 98.3 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Abnormal | 5 | 2.9 | 1 | 1.8 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 5.25 | 0.64 | 0.76 | 0.09 | 6.83 | 0.81 |

| Abnormal Cranial Ultrasound | ||||||||||||

| Normal | 145 | 83.8 | 44 | 77.2 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Abnormal | 28 | 16.2 | 13 | 22.8 | 1.53 | 0.73 | 3.21 | 0.26 | 1.65 | 0.77 | 3.50 | 0.20 |

| Peri-Operative | ||||||||||||

| Operation type | ||||||||||||

| No CPB | 26 | 15.0 | 7 | 12.3 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| CPB/CPB standby | 147 | 85.0 | 50 | 87.7 | 1.26 | 0.52 | 3.09 | 0.61 | 1.28 | 0.52 | 3.16 | 0.60 |

| Perfusion Time (mins) (median, range) | 156 | 122.5 (0–363) | 53 | 104 (0–296) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.51 |

| Cross clamp time (mins) (median, range) | 156 | 156 (0–321) | 53 | 44 (0–149) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Delayed_Closure | 124 | 71.7 | 43 | 75.4 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| No | 49 | 28.3 | 14 | 24.6 | 0.82 | 0.41 | 1.64 | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.38 | 1.55 | 0.46 |

| Yes | ||||||||||||

| Need for dialysis | ||||||||||||

| No | 171 | 98.8 | 56 | 98.3 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.8 | 1.53 | 0.14 | 17.16 | 0.73 | 1.35 | 0.12 | 15.59 | 0.81 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | ||||||||||||

| No | 160 | 92.5 | 50 | 87.7 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 13 | 7.5 | 7 | 12.3 | 1.72 | 0.65 | 4.56 | 0.27 | 1.72 | 0.64 | 4.61 | 0.28 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia | ||||||||||||

| No | 109 | 63.0 | 41 | 71.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 64 | 37.0 | 16 | 28.1 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 1.28 | 0.22 | 0.63 | 0.33 | 1.23 | 0.18 |

| Seizure Activity | ||||||||||||

| No | 152 | 87.9 | 52 | 91.2 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 21 | 12.1 | 5 | 8.8 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 1.94 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 1.97 | 0.50 |

| Post-Operative | ||||||||||||

| Failed Vision Screening | ||||||||||||

| Pass | 169 | 97.7 | 50 | 87.7 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Fail | 4 | 2.3 | 7 | 12.3 | 5.92 | 1.66 | 21.03 | 0.006 | 6.42 | 1.76 | 23.42 | 0.005 |

| Failed Hearing Screening | ||||||||||||

| Pass | 168 | 97.1 | 52 | 91.2 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Fail | 5 | 2.9 | 5 | 8.8 | 3.23 | 0.90 | 11.60 | 0.07 | 2.83 | 0.77 | 10.37 | 0.12 |

| Gastrostomy Tube | ||||||||||||

| No | 107 | 61.9 | 33 | 57.9 | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Yes | 66 | 38.2 | 24 | 42.1 | 1.18 | 0.64 | 2.17 | 0.60 | 1.12 | 0.61 | 2.08 | 0.71 |

| Length of Stay (days) (median, range) | 173 | 43 (5–329) | 57 | 38 (1–206) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.23 |

| Length of Ventilation (days) (median, range) | 171 | 5 (1–78) | 57 | 6 (1–138) | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.20 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.33 |

Appropriate for gestational age

Small for gestational age

Odds ratio

Lower confidence limit

Upper confidence limit

Utility of Small for Gestational Age versus Low Birth Weight in Predicting Mortality

Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis revealed that both the identification of infants who were small for gestational age and who were low birth weight predicted mortality at 30 days and mortality at discharge fairly well (all area under the curve ≥ 0.6). In comparing small for gestational age to low birth weight as a better predictor of mortality, we did not observe a difference in the predictive value of these two measures for all participants (all p≥0.42) or when limited to combined Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery mortality categories 4 and 5 (p≥0.44).

Discussion

Small for gestational age and low birth weight are important predictors of mortality in infants with congenital heart disease undergoing cardiothoracic surgery under 60 days of age. Our data demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mortality at 30 days in all small for gestational age infants versus appropriate gestational age (p=0.005), low birth weight infants versus normal birth weight (p=0.04) and small for gestational age infants with normal birth weights >2500 grams (p=0.045) as well as increased mortality at discharge in small for gestational age infants (p=0.0345) and low birth weight infants (0.026). Infants who are born small for gestational age may be smaller due to constitutional issues or may have foetal growth restriction due to a pathological process in the environment, mother, placental or foetus. Our small for gestational age population had a mean gestational age of 37.1 weeks which limited prematurity as a confounding variable. In addition, the surgical procedures performed when stratified by the Society for Thoracic Surgeons and –European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery Congenital Heart Surgery mortality categories were comparable (mean score of 3.51 for SGA and 3.75 for AGA). Our surgical outcomes were comparable to nationally reported averages (see Table 6). Mortality categories 4 and 5 compromised a majority of infants studied, 71.7%. The bulk of these category 4 and 5 procedures, 61.2%, were palliative including pulmonary artery banding, modified Blalock-Taussig shunts and Stage 1 Norwood procedures (Table 2).

Table 6.

Society of Thoracic Surgeons – European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgeons (STS-EACTS) Mortality Category Classification for a Cohort of 230 Infants at a Single Institution Compared to Nationally Reported Outcomes.

| STS-EACTS Mortality Categories | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| STS-EACTS Nationally Reported Mortality** | 0.8% | 2.6% | 5.0% | 9.9% | 23.1% |

| Mortality Reported at time of discharge from our cohort of 230 patients | 16.7% (n=1/6) | 2.4% (n=1/42) | 0% (n=0/17) | 13.6% (n=16/118) | 23.4% (n=11/47) |

O’Brien SM, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009; 138:1139–1153.

The hypothesis that factors affecting fetal development subsequently result in pediatric and adult disease has been well described and is known as the Barker Hypothesis.9 Since Barker’s initial publications presenting the association between infant mortality and early ischemic coronary heart disease, fetal growth restriction has been linked with developing early systemic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, chronic lung disease, reduced renal function, poor academic performance, low social competence and behavioral/affective disorders.9–16 Low birth weight has been shown in various studies to be a risk factor for mortality and morbidity in infants undergoing cardiothoracic surgery for congenital heart disease.2,3,7,8 Pre-operative screening programs to assess for secondary co-morbidities vary by surgical center and usually do not include assessment of fetal growth restriction. Our study demonstrated that having an assessment of fetal growth (the determination of small for gestational age) may be helpful in predicting the overall outcome of infants undergoing cardiothoracic surgery. We also demonstrated that small for gestational infants with a normal weight >2500 grams are also at risk of increased mortality and should not be over looked by practitioners. The calculation of small for gestational can be easily done on admission done upon admission to the hospital and may be a useful adjunct to the pre-operative screening protocol and risk stratification of patients with critical congenital heart disease.

Small for gestational age and low birth weight infants were both interestingly not associated with additional pre-operative co-morbidities (genetic anomalies, renal anomalies or CNS anomalies), and peri-/post-operative end-organ morbidities (need for dialysis, need for extracorpeal membrane oxygenation, seizures, need for gastrostomy tube, hearing abnormality, length of ventilation or length of stay). Small for gestational age has been associated with a variety of chronic adult end organ disease as listed above. We therefore acknowledge that small for gestational age infants with critical congenital heart disease may have the potential to develop end-organ dysfunction in later life; but our data infers they appear to have adequate end-organ reserve to successfully overcome the stress of cardiopulmonary bypass and a cardiothoracic surgical procedure without significant acute end organ failure. The exception to this was vision exams which were abnormal in the small for gestational age infants compared to the appropriate for gestational age infants. This is consistent with a recent report that demonstrated that small for gestational infants were prone to develop low visual acutity.18

Limitations of this study include its inherent retrospective design and limited sample size. Further studies should be prospective or focused on larger, multi-center databases. Special interest could be placed on infants born who are small for gestational age with and without normal birth weight to delineate further differences in this patient population.

Conclusion

Pre-operative assessment for fetal growth restriction in infants with critical congenital heart disease, identifies a subgroup of patients at increased risk of surgical mortality. Infants born small for gestational age who are also normal birth weight may have increased mortality. Assessment of fetal growth restriction may be useful in a pre-operative screening protocol. Preoperative family counseling and education should be given to the families of small for gestational age infants with critical congenital heart disease, which includes the increased risk of mortality during surgical procedures and potential life-time risk of end organ dysfunction including visual dysfunction.

References

- 1.Van der Linde D, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC. 2011;58(21):2241–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curzon CL, et al. Cardiac surgery in infants with low birth weight is associated with increased mortality: Analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Disease. J Thorac Cariovasc Surg. 2008;135(3):546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ades AN, et al. Morbidity and mortality after surgery for congenital heart disease in the infant born low weight. Card in the Young. 2010;(1):8–17. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109991909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik S, et al. Association between congenital heart defects and small for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e976–e982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton TR. A new growth chart for preterm babies: Babson and Benda’s chart updated with recent data and a new format. BMC Pediatrics. 2003;3:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien SM, et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1139–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy VM, et al. Results of 102 cases of complete repair of congenital heart defects in patients weighing 700 to 2500 grams. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999 Feb;117(2):324–31. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ades A, Johnson BA, Berger S. Management of low birth weight infants with congenital heart disease. Clin Perinatol. 2005 Dec;32(4):999–1015. x–xi. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boo HA, Harding JE. The developmental origins of adult disease (Barker) hypothesis. Australian and New Zealand J of Ob/Gyn. 2006;46:4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker DJ, Bull AR, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ. Foetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. Br Med J. 1990;301:259–262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia. 1993;36:62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00399095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newsome CA, Shiell AW, Fall CH, Phillips DI, Shier R, Law CM. Is birth weight related to later glucose and insulin metabolism? – A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2003;20:339–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lal MK, Manktelow BN, Draper ES, Field DJ. Chronic lung disease of prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:483–487. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hack M, Youngstrom EA, Cartar L, et al. Behavioral outcomes and evidence of psychopathology among very low birth weight infants at age 20 years. Pediatrics. 2004;114:932–940. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1017-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundgren EM, Tuvemo T. Effects of being born small for gestational age on long-term intellectual performance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jun;22(3):477–88. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berle JO, et al. Outcomes in adulthood for children with foetal growth retardation. A linkage study from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) and the Medical Birth Registry of Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006 Jun;113(6):501–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooke RW. Conventional birth weight standards obscure fetal growth restriction in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92(3):F189–92. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.089698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinello L, Manea S, Visona Dalla Pozza L, et al. Visual, motor and psychomotor development in small for gestational age preterm infants. J AAPOS. 2013 Aug;17(4):352–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]