Abstract

The authors examined how ambivalence toward adult children within the same family differs between mothers and fathers and whether patterns of maternal and paternal ambivalence can be explained by the same set of predictors. Using data collected in the Within-Family Differences Study, they compared older married mothers’ and fathers’ (N = 129) assessments of ambivalence toward each of their adult children (N = 444). Fathers reported higher levels of ambivalence overall. Both mothers and fathers reported lower ambivalence toward children who were married, better educated, and who they perceived to hold similar values; however, the effects of marital status and education were more pronounced for fathers, whereas the effect of children’s value congruence was more pronounced for mothers. Fathers reported lower ambivalence toward daughters than sons, whereas mothers reported less ambivalence toward sons than daughters.

Keywords: ambivalence, families in middle and later life, intergenerational relations, parent – child relations

Over the past decade, one of the most important theoretical and empirical contributions regarding aging families has been the recognition of complexity and multiplicity in parent – adult child relations (Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010). A number of family scholars have moved from traditional measures of parent – adult child closeness or conflict toward the study of a more complex interplay of positive and negative components of the relationship. One of the most consistent findings from this line of research is that both parents and their adult children experience feelings of ambivalence about one another (Birditt, Fingerman, & Zarit, 2010; Connidis & McMullin, 2002; Luescher & Pillemer, 1998; Peters, Hooker, & Zvonkovic, 2006; Pillemer et al., 2007; van Gaalen & Dykstra, 2006; Willson, Shuey, & Elder, 2003).

Surprisingly little attention, however, has been paid to fathers’ experiences of intergenerational ambivalence. Given well-established differences between mothers and fathers in the overall quality of intergenerational relationships (Biblarz & Stacey, 2010; Suitor, Sechrist, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2011), we believe that the role of gender in ambivalence toward adult children is worthy of further investigation. In this article, we focus on two research questions: (a) Does the level of intergenerational ambivalence within the same family differ between mothers and fathers and (b) can mothers’ and fathers’ patterns of ambivalence be explained by the same combination of social structural and individual factors?

Conceptualizing Ambivalence

Of importance to the approach in this article is the conceptualization of intergenerational ambivalence, on which there has been substantial progress over the past decade. Luescher and Pillemer’s (1998) initial formulation distinguished two dimensions of ambivalence: (a) sociological ambivalence, which highlights contradictory norms that may ultimately affect parent – child relations, and (b) psychological ambivalence, which is experienced on the individual level. They differentiated between contradictions at the level of social structure and contradictions on the subjective level (e.g., emotions). Connidis and McMullin (2002) used the framework of critical theory to reconceptualize the relationship between these two levels, more explicitly linking the contradictions produced by social structure to individual action. In their view, contradictions in socially structured relations are reproduced in family relationships, which individuals in turn must negotiate. Despite conceptual differences, however, these and subsequent frameworks (Lüscher, 2004; Rappoport & Lowenstein, 2007) agree on the tenet that the social structural positions individuals occupy affect their emotions in intergenerational relationships.

In this article, we focus specifically on psychological ambivalence as the outcome variable. Psychological ambivalence has been a topic of interest for several decades in attitudinal research (Lettke & Klein, 2004). In this literature, ambivalence is typically defined as holding both positive and negative emotions or attitudes simultaneously (Suitor, Gilligan, & Pillemer, 2011; Weigert, 1991). Most researchers have similarly defined intergenerational ambivalence as “simultaneously held opposing feelings or emotions that are due in part to countervailing expectations about how individuals should act” (Connidis & McMullin, 2002, p. 558; see also Rappoport & Lowenstein, 2007; Suitor et al.; Ward, Spitze, & Deane, 2009). In this study, we examined how the experience of psychological ambivalence toward adult children is affected by gender, focusing on the experience of older mothers and fathers. Following Luescher and Pillemer (1998), Connidis and McMullin (2002), and others, we also focused on occupying social statuses as predictors of ambivalence.

Are Mothers or Fathers More Ambivalent?

On the basis of the existing theoretical and empirical literature, we hypothesized that mothers will experience significantly lower levels of ambivalence toward their offspring than fathers. We grounded this hypothesis in theory and research regarding motherhood throughout the life course. As noted, psychological ambivalence is constituted by the simultaneous presence of positive and negative feelings toward a child (Lettke & Klein, 2004); thus, the greater the intensity of both positive and negative feelings, the higher the level of ambivalence. We suggest that ambivalence is likely to be lower among mothers because of their tendency toward positive rather than negative assessments of relationships with their children.

This positive tendency occurs because of mothers’ heightened investment in the parent – child tie and because of traditional notions of womanhood that define femininity in terms of motherhood. Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1951, 1958; Merz, Schuengel, & Schulze, 2007) suggests that because mothers are usually the primary caregivers of children (Coltrane, 2000; Hochschild, 1989), mothers and children have warmer relationships compared to fathers. Research has substantiated this claim. Mothers generally are more positive, supportive, and affectionate toward their children than fathers, and children report feeling more closely attached to their mothers than to their fathers (Bengtson, 2001; Fingerman, 2001; Rossi & Rossi, 1990; Umberson, 1992; Ward, 2008). It is therefore likely that mothers will tend toward univalent positive evaluations of the relationship, rather than mixed positive and negative emotions.

Furthermore, women’s role as primary caregivers may lead mothers, as opposed to fathers, to be more invested in the parent – child tie (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006; Rossi & Rossi, 1990). Throughout the life course, mothers act as kinkeepers, maintaining family bonds (Bengtson, Rosenthal, & Burton, 1990; Hagestad, 1998; Rossi, 1993; Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2008). Both sons and daughters interact more with their mothers than their fathers and report a higher quality of affect and attachment with them than with fathers (Buist, Dekovic, Meeus, & van Aken, 2002). This role may lead women to report more positive and fewer negative feelings (and therefore less ambivalence) toward adult children than do fathers.

A third reason we expected mothers to report less ambivalence than fathers is that motherhood is entwined with notions of femininity (Chodorow, 1978, 1989; Glenn, 1994). Particularly for women born in the 1930s and 1940s (as were the women in our sample), mothering is a more powerful identity than either marital status or occupation (McMahon, 1995; Rogers & White, 1998). Thus, there is a potential cohort effect, because older women may define themselves more strongly in terms of motherhood than younger women. Therefore, the general tendency toward positivity just outlined may be more pronounced for older mothers, inclining them to focus more heavily on the positive aspects of the relationship and to exclude negative aspects. For these reasons, although we expected to uncover intergenerational ambivalence on the part of both mothers and fathers, we expected mothers to report lower levels of ambivalence than fathers.

Parents’ Gender and Factors Related to Ambivalence

Thus far, we have limited our discussion to gender differences in intergenerational ambivalence without considering the circumstances that might give rise to it. Our second research question asked whether mothers’ and fathers’ patterns of ambivalence can be explained by the same factors identified in earlier research. Over the past decade, we and our colleagues have developed a conceptual framework for explaining parental ambivalence that emphasizes competing norms and status attainment (Pillemer & Suitor, 2002; Pillemer et al., 2007). In this framework, ambivalence is hypothesized to result when incompatible normative expectations for relationships with children produce contradictory feelings toward them. This perspective builds on classic theoretical perspectives on sociological ambivalence by Merton and Barber (1963) and Coser (1966), who posited that incompatible normative expectations constitute structural sources of ambivalence for individuals.

In the case of intergenerational ambivalence, the literature consistently points to children’s failure to achieve or maintain normative adult statuses—such as becoming married, becoming a parent, and being employed—as producing heightened ambivalence (Cohler & Grunebaum, 1981; Fingerman, Chen, Hay, Cichy, & Lefkowitz, 2006; Pillemer & Suitor, 2002). Specifically, there is evidence that a general underlying cause of parental ambivalence lies in the conflict between the norm of intergenerational solidarity mandating help for adult children in need and normative expectations that children should be successfully launched in adulthood (Birditt et al., 2010; George, 1986; Luescher & Pillemer, 1998). Furthermore, research has shown that conflict between these two norms—pressure to help adult children but a desire for freedom from their demands—specifically produces ambivalence, rather than simply conflict or tension (Pillemer, 2004; Pillemer & Suitor; Teo, Graham, Yeoh, & Levy, 2003; Willson et al., 2003).

In these situations, conflict occurs between the norm of solidarity with children and the normative expectation that children should become independent adults (Bengtson, Giarrusso, Mabry, & Silverstein, 2002); parents may feel obligated to protect and support children on the one hand, while simultaneously desiring them to be launched into independent lives (George, 1986; Luescher & Pillemer, 1998). When children do not fulfill expectations for normal adult development, parents continue to desire contact and to express solidarity toward the child while simultaneously feeling disappointment about the child’s life and self-doubt regarding parenting (Luescher & Pillemer). Empirical support for this pattern has been found in studies of mothers (Pillemer & Suitor, 2002; Pillemer et al., 2007) and for both mothers and fathers (Birditt, Miller, Fingerman, & Lefkowitz, 2009). Thus, consistent with previous theory and research, we predicted that both mothers and fathers will report less ambivalence toward married children than single children, toward more educated children than less educated children, and toward employed children than unemployed children.

Although we expected both men and women to report less ambivalence toward children who have attained normative adult statuses, there was also reason to hypothesize that men and women will differ in the degree to which status attainment variables predict ambivalence toward children. Because men tend to emphasize instrumental issues in their interactions and relationships more than women (Maccoby, 1998; Webster & Rashotte, 2009), it is likely that fathers will value moving into traditional adult statuses, such as employment, education, and marriage, more than mothers. We therefore predicted that both parents will report significantly less ambivalence toward children who achieve higher levels of education, who are employed, and who are married but that this effect will be more pronounced among fathers than mothers.

This framework also highlights the importance of a second predictor of intergenerational ambivalence: value consensus between parent and child (Pillemer & Suitor, 2002; Pillemer et al., 2007). We hypothesized that a consensus on values will play a stronger role in shaping mothers’ ambivalence than fathers’ ambivalence toward their adult children. Theorists have suggested that mothers are more heavily invested in reproducing their values and identity in their offspring than are fathers (Chodorow, 1978; Gilligan, 1982, Rossi & Rossi, 1990). Studies of intergenerational solidarity have shown that mothers typically have a greater investment in solidarity with children, although differences in consensual solidarity specifically have not been found (Silverstein & Bengtson, 1997). Furthermore, in a direct comparison of predictors of mothers’ and fathers’ reports, a consensus on values was a much stronger predictor of mothers’, as opposed to fathers’, relationship quality with a child (Suitor & Pillemer, in press). Given these findings, we hypothesized that value consensus will play a more important role in predicting mothers’ ambivalence toward their adult children than fathers’ ambivalence.

Finally, we explored the effect of child’s gender on intergenerational ambivalence for mothers and fathers. Both parents’ gender and children’s gender seem to play an important role in fostering intergenerational relations. The preponderance of studies has reported the strongest affectional ties between mothers and daughters and the least closeness between fathers and sons (Rossi & Rossi, 1990; Spitze, Logan, Deane, & Zerger, 1994; Suitor & Pillemer, 2006). Because ambivalence is a more complex relational dimension than is closeness, however, it may not be reasonable to make predictions regarding ambivalence based on patterns found for closeness.

The empirical literature provides little guidance regarding the role of child’s gender in intergenerational ambivalence. Studies of mothers have found no differences in ambivalence based on child’s gender (Pillemer, 2004; Pillemer & Suitor, 2002; Willson, Shuey, Elder, & Wickrama, 2006); however, there is suggestive evidence from studies of adult children that the mother – daughter and father – son ties may be more ambivalent. Willson and colleagues (2003) found the mother – daughter pair was most ambivalent, from the adult child’s perspective. Van Gaalen, Dykstra, and Komter (2010) used measures of solidarity and conflict to classify families into several types and found that ties between fathers and sons had a higher probability of falling into the negative ambivalence family type. Given the limited and inconsistent nature of these findings, we do not propose specific hypotheses regarding which parent – child pairs are likely to be the most ambivalent.

Summary of Research Questions

In summary, we addressed two research questions. First, does the level of intergenerational ambivalence within the same family differ between mothers and fathers? Second, can mothers’ and fathers’ patterns of ambivalence be explained by the same combination of social structural and individual factors, or will predictors differ according to parents’ gender? We hypothesized that mothers will experience lower levels of ambivalence toward their adult children. Furthermore, we hypothesized that there will be gender differences in the predictors of ambivalence; specifically, we expected that the achievement of normative adult statuses (e.g., educational attainment, employment, marital status) will be a stronger predictor of ambivalence for fathers, whereas value consensus will be a stronger predictor of ambivalence for mothers. We did not propose specific hypotheses regarding the role of child’s gender or the interaction of parent – child gender in predicting intergenerational ambivalence.

Method

Sampling

The data for this article were collected as part of the Within-Family Differences Study (Suitor & Pillemer, 2006). The design involved selecting a sample of mothers 65 through 75 years of age with at least two living adult children and collecting data from mothers regarding each of their children. Only community-dwelling mothers were included in the sample. Massachusetts city and town lists were the source of the sample. Massachusetts requires communities to keep city/town lists of all residents by address. Town lists also provide the age and gender of residents.

With the assistance of the University of Massachusetts, Boston, we drew a systematic sample of women ages 65 through 75 from the town lists of 20 randomly selected communities in the greater Boston Census-designated Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area. An equal number of women in the target age group were selected from each community. The interviewers began contacting potential respondents and continued until they had completed interviews with 566 mothers, which represented 61% of those who were eligible for participation. The interviews were conducted between August 2001 and January 2003.

Two hundred sixty-nine (48%) of the respondents were married. At the end of each interview, married participants were told about the study component involving their husbands and were asked for their permission to contact them. Sixty-eight percent of the married mothers gave permission for the interviewers to contact their husbands; 78% of the husbands agreed to participate, resulting in a final sample of 129 husbands. Because the central research questions of this article revolve around differences between mothers and fathers within the same family, we limited the data to the responses of the 129 fathers and the 129 mothers married to these fathers. Interviews with the fathers and mothers lasted between 1 and 2 hours. These parents reported about aspects of relationships, including ambivalence, with each of their adult children, resulting in data on 444 offspring.

Sample Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of mothers, fathers, and their adult children are presented in Table 1. All mothers in this subsample identified themselves as Black or White. In the full sample, 73% of the mothers were White; however, in the married subsample, 95% of the mothers were White. This pattern is due to the higher rates of remaining single, becoming divorced, and becoming widowed among Black than White women (Liddon, Leichliter, Habel, & Aral, 2010; Marsh, Darity, Cohen, Casper, & Salters, 2007; U.S. Census Bureau, 2006).

Table 1.

Demographic Information for Mothers, Fathers, and Adult Children (N = 699)

| Variable | Mothers (n = 129) | Fathers (n = 129) | Adult Children (n = 441) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (M, SD) | 69.6 (3.3) | 70.6 (4.5) | 41.6 (5.5) |

| Married (%) | 70.7 | ||

| Education (%) | |||

| Less than high school | 9.3 | 12.4 | 2.8 |

| High school graduate | 28.7 | 24.0 | 17.7 |

| At least some college | 17.8 | 8.5 | 10.7 |

| College graduate | 36.5 | 50.4 | 66.0 |

| Employed (%) | 28.7 | 38.0 | 86.3 |

| Race (% Black) | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| No. children (M, SD) / percentage children with offspring |

3.4 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.5) | 70.7 |

| Adult children’s gender (% daughters) | 49.0 |

Although the mean number of living children in our sample was higher than would be found in a nationally representative sample of women in this age group, this is primarily due to the criterion that all participants must have at least two living adult children. The mean number of children in our sample was similar to that found in national samples, such as the National Survey of Families and Households (Sweet & Bumpass, 1996), when compared specifically to mothers in the same age group who have two or more children.

Measures

Ambivalence

Following previous conceptual work and research on ambivalence, we defined ambivalence operationally as experiencing mixed or contradictory emotions toward the same individual (Raulin, 1984; Sincoff, 1990; Weigert, 1991). We directly assessed subjective perceptions of ambivalence by asking respondents the degree to which their attitudes toward each child were mixed or conflicted. The format of the measures was based on previous work by Kelley (1983); Thompson, Zanna, and Griffin (1995); and Sincoff (1990), all of whom used direct measures of ambivalence in studies of close relationships. The content of the items was developed in pilot studies that were carried out to guide instrument development (for further details on measure development, see Suitor et al., 2011).

Two global questions about ambivalent feelings were used. First, on the basis of the pilot research, both mothers and fathers were asked identical items about the degree to which they felt “torn in two directions or conflicted” about the child (0 = never, 1 = seldom, 2 = now and then, 3 = often, 4 = very often). A second item asked respondents to what degree they had “very mixed feelings” toward the child. The response categories were 0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = agree, and 3 = strongly agree. To maintain these two items on a comparable scale, values of 4 in response to the question of how torn mothers and fathers felt in a particular relationship were recoded to 3. The correlation between the two items was .51. Summed scores for this direct measure of ambivalence ranged from 0 to 6 (M = 2.23; SD = 1.56; r = .51, p < .001).

Independent variables

The independent variable of primary interest was parent’s gender, which was coded as 0 for mothers and 1 for fathers. Child’s gender was coded 0 for sons and 1 for daughters. Forty-nine percent of the children in the sample were daughters.

Attainment of adult statuses

Four variables were used to indicate adult children’s successful completion of transitions to normatively prescribed social statuses: (a) marital status (1 = married, 0 = not married; 56% were married), (b) parental status (1 = has children, 0 = does not have children; 70% had children), (c) educational attainment (1 = less than high school; 2 = some high school; 3 = high school graduate; 4 = post-high school vocational; 5 = some college; 6 = college graduate; and 7 = completed graduate school; M = 2.35, SD = 0.63), and (d) employment status (1 = employed, 0 = not employed; 86% employed).

Value consensus

The item used in this study was developed by Rossi and Rossi (1990) in their classic study of intergenerational relationships, which they designed to tap consensus in parents’ and children’s values. Value consensus was measured by asking respondents,

Parents and children are sometimes similar to each other in their views and opinions and sometimes different from each other. In your general outlook on life, would you say that you and [child’s name] share very similar views and opinions (4), similar views and opinions (3), different views and opinions (2), or very different views and opinions (1)? (M = 2.77, SD = 0.84).

Control variables

We included in the analysis several variables that have previously been found to be related to ambivalence or to inter-generational relationship quality more generally, including parents’ age (in years) and parents’ race (see Table 1). Parents’ self-reported health was measured with five categories (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent; M = 3.26, SD = 1.10). Geographical proximity was measured on a 5-point scale (1 = same house, 2 = same neighborhood, 3 = within a 15-minute drive, 4 = within a 15- to 30-minute drive, 5 = within a 30- to 60-minute drive, 6 = over an hour drive; M = 4.44, SD = 1.89). Finally, prior research indicates that problems perceived as voluntary and deviant in nature (e.g., problems with drugs, problems with the law) are related to ambivalence. We asked mothers whether each of their children had experienced, as adults, a series of problems that individuals might face. Two of these items were considered deviant: (a) “problems with drinking or drugs” and (b) “problems with the law.” Respondents were coded as follows: 0 = neither problem and 1 = at least one problem; 14% of children had experienced = such voluntary problems

Analytic Plan

Throughout, the parent – child dyad, rather than the parent, was the unit of analysis. In other words, the 444 children who were the units of analysis are nested within the 129 families on whose reports the present analysis is based; furthermore, we used reports from both mothers and fathers; thus, the observations are not independent. To take this into account, we used multilevel random coefficient modeling (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Three-level models were estimated to address the hypotheses of interest. An unconditional (null) model, with no predictors, was initially estimated to partition the variance in parental ambivalence across the three levels: (a) between families (Level 3), (b) between children within families (Level 2), and (c) between parents within children (Level 1). A second model added a dummy variable for father. This model allowed us to determine whether fathers reported significantly higher or lower levels of ambivalence than mothers. A third model added predictors of parental ambivalence. The purpose of this model was twofold: (a) to replicate previous findings relating to predictors of parental ambivalence based on maternal reports and (b) to determine whether differences between mothers and fathers might be accounted for by these variables. A fourth and final model added interactions with a father-indicator variable to determine whether the effect of each predictor was stronger or weaker for fathers than for mothers. As a result, it was possible to determine the differential effects of predictors for mothers and fathers. Results for Models 1 through 4 are presented in Table 2. All parameter estimates shown in Table 2 are unstandardized.

Table 2.

Multilevel Parameter Estimates for Parental Ambivalence (N = 441)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimates |

Unstandardized Coefficient |

SE | Unstandardized Coefficient |

SE | Unstandardized Coefficient |

SE | Unstandardized Coefficient |

SE |

| Intercept | 2.33*** | 0.08 | 2.17*** | 0.10 | 2.64*** | 0.20 | 2.44*** | 0.21 |

| Father | .29*** | 0.09 | 0.25** | 0.10 | 0.65*** | 0.18 | ||

| Parent age | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | ||||

| Parent race | −0.47 | 0.34 | −0.46 | 0.34 | ||||

| Parent health | −0.12 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.06 | ||||

| Child female | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.23† | 0.13 | ||||

| Child marital status | 0.64*** | 0.13 | −0.50* | 0.16 | ||||

| Child has children | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.13 | ||||

| Child education | −0.16* | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.08 | ||||

| Child employed | −0.11 | 0.15 | −0.19 | 0.14 | ||||

| Child deviant problems | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.18 | ||||

| Child value similarity | 0.32*** | 0.05 | −.42*** | 0.06 | ||||

| Child proximity | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | ||||

| Father × Child female | −0.40* | 0.17 | ||||||

| Father × Child marital status | −0.31† | 0.19 | ||||||

| Father × Child education | −0.22* | 0.09 | ||||||

| Father × Child similarity | 0.22* | 0.09 | ||||||

| Variance components | ||||||||

| Family | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.49 | ||||

| Family × Child | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Residual | 1.63 | 1.59 | 1.51 | 1.48 | ||||

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Null Model: Variance Decomposition

Model 1 estimated an overall intercept and three variance components. The estimated variances suggest that 25% of the variability in parental ambivalence toward children existed across families (at Level 3), 6% existed across children within families (Level 2), and 69% existed across parents within children (Level 1). These estimates suggest that a substantial portion of the variance in parental ambivalence can be explained by family characteristics, including shared child characteristics (25%), whereas a relatively small amount of the variance can be explained by unique child characteristics (6%). The remaining 69% of the variance can be attributed to unique parent characteristics or reporting tendencies. Thus, substantially more of the variance in parental ambivalence scores is attributable to parent characteristics, rather than deriving from child factors.

Results

Differences Between Mothers and Fathers

The results of the multilevel analysis are presented in Table 2. Model 2 shows differences between mothers and fathers in levels of ambivalence. As predicted, fathers reported higher levels of ambivalence toward their children than did mothers (B = .294, SE = .087, p < .001).

Predictors of parental ambivalence

The findings shown in Model 3 support our hypotheses that parents were less ambivalent toward children who were married (B = .644, SE = .130, p < .001) and toward children who were better educated (B = −.159, SE = .063, p = .012). In addition, parents reported less ambivalence toward children whom they perceived to be more similar to themselves (B = .323, SE = .049, p < .001). Contrary to our hypotheses, however, we did not find that parents expressed less ambivalence toward children who were employed (B = −.107, SE = .145, p = .462).

After accounting for the various predictors of parental ambivalence, mother and father differences decreased only slightly and remained highly significant (B = .251, SE = .095, p = .008). This suggests that differences in levels of ambivalence between parents were not fully explained by parent differences in age, health, or perceptions of similarity. Interactions between child’s gender and each of the status attainment variables (marital status, employment status, and level of education) also were considered but were not found to be significant.

Differences between mothers and fathers in predictors of ambivalence

Having established predictors of ambivalence, Model 4 tested whether the effects of each predictor were significantly stronger or weaker for fathers than for mothers. In other words, we allowed the coefficient for each predictor to vary across mothers and fathers and tested the significance of these differences. The findings from this model suggest several differences between mothers and fathers that are consistent with our hypotheses.

First, children’s marital status was a stronger predictor of ambivalence for fathers than for mothers (B = −.314, SE = .191, p = .100). Second, educational attainment was a substantially stronger predictor for fathers than mothers (B = −.217, SE = .086, p = 012). Fathers reported less ambivalence toward children who achieved higher levels of education, whereas mothers did not. These findings suggest that the main effect of child’s education on parental ambivalence was almost entirely driven by fathers. Third, value consensus played a stronger role in the levels of ambivalence expressed by mothers than fathers (B = .224, SE = .091, p = 014). The only finding counter to our hypotheses from this set of interactions was that fathers did not report lower ambivalence toward employed children than did mothers.

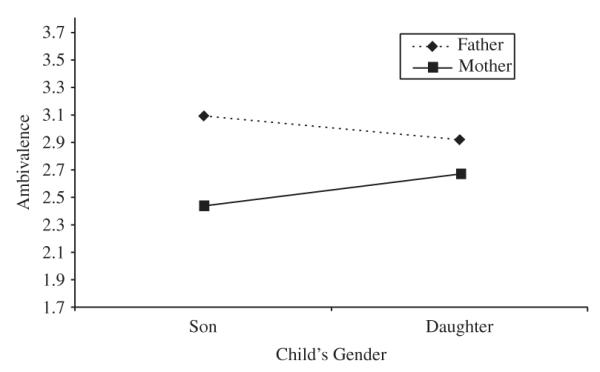

Finally, we found that the effects of child gender on ambivalence differed for mothers and fathers; specifically, fathers tended to report more ambivalence toward sons than daughters, whereas mothers were more ambivalent toward daughters than sons (B = −.404, SE = .171, p = .018). This effect is depicted in Figure 1. After all predictors had been added to the model, 16% of the overall variance in parental ambivalence had been accounted for. Specific variance component estimates suggested that essentially all of the variance across children within families (Level 2) was accounted for by the predictors. Furthermore, 17% of the variance across families (Level 3) and 9% of the variance across parents within children (Level 1) was explained.

Figure 1.

Fitted Interaction Plot Depicting Levels of Ambivalence Toward Sons and Daughters for Mothers and Fathers.

These findings raise the important issue of which types of effects, and at what levels—child, family, or external—have the most influence on parental ambivalence. The best evidence comes from our final model, Model 4. Both the family and child levels were predictive of parental ambivalence. Fixed factors that were explicitly modeled, such as the child’s similarity and marital status, were predictive. Once these factors were accounted for, the estimated child variance was negligible. In contrast, only gender of parent among variables explicitly modeled at the family level was significantly predictive, albeit highly significantly, and the variance component for family was larger. These results suggest that future research should highlight parental characteristics in predicting ambivalence, as well as a continuing focus on both levels, including an attempt to obtain a better estimate of child variance and to determine other family-level variables that may be significant.

Discussion

In this research, we addressed the fundamental question “Does gender matter in understanding ambivalence in parent – child relations in later life?” The results strongly suggest that gender does indeed matter, showing that the experience of ambivalence differs substantially between mothers and fathers in the same family. First, consistent with our hypotheses, mothers reported lower levels of ambivalence toward adult children. Given other support for this finding (Willson et al., 2006), researchers should begin to explore the mechanisms leading to greater ambivalence among older fathers than mothers. We hypothesized that ambivalence is lower because mothers tend to be more invested in the parent – child tie and to focus on positive rather than negative aspects of their relationships with their children, whereas fathers balance stronger negative feelings with positive ones. Additional research (both quantitative and qualitative) is needed to explore this hypothesis, focusing on the mechanisms for the gender differences.

Second, gender was again of substantial importance when we examined the factors that predicted intergenerational ambivalence. We found that children’s marital status and children’s educational attainment were stronger predictors of ambivalence for fathers than for mothers. We speculate that this pattern occurred because men emphasize instrumentality more than women (Maccoby, 1998; Webster & Rashotte, 2009) and hold more traditional gender role attitudes than women (Davis & Greenstein, 2009). On the other hand, value similarity played a stronger role in the levels of ambivalence expressed by mothers than fathers. This finding bolsters research (Suitor & Pillemer, in press) that has found similarity of values to be a much stronger predictor of mothers’ relationship quality with children than of fathers’.

Third, the findings of this study highlight the effect of child’s gender on intergenerational ambivalence for mothers and fathers. We expected that intergenerational ambivalence would vary across the four family dyads (mother – daughter, mother – son, father – daughter, father – son), although we did not predict the direction of the effects. The findings of greater ambivalence in mother – son and father – daughter dyads are consistent with research showing that gender is a primary frame for organizing social relations (Maccoby, 1990, 2003). The finding that that fathers reported greater ambivalence toward sons whereas mothers reported greater ambivalence toward daughters was somewhat surprising, though. The results we uncovered run counter to the pattern seen when studying closeness between mothers and their adult children, in which gender similarity is associated with greater closeness (Rossi & Rossi, 1990; Spitze et al., 1994; Suitor & Pillemer, 2006).

This finding suggests that ambivalence measures a relationship domain that is distinct from closeness. Again, we can only speculate as to the causes of this pattern; however, an intriguing possibility is that competing roles in the daughter generation, as discussed by Connidis and McMullin (2002), make a difference, even if they are not salient for older mothers. The role of wife and mother has been found to reduce contact with and assistance to older parents (Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2008). Mothers may feel this separation more acutely (and more ambivalently) than fathers. Other than the present study, there is a dearth of literature that has systematically examined intergenerational ambivalence, including all four relationship dyads. To advance our understanding of intergenerational ambivalence, research is needed that explores this issue in more detail.

The study has several limitations that point toward future directions for research. First, one potential bias is the lack of heterogeneity in the sample. The participants were all married, heterosexual, older adults who self-identified as either Black or White. Connidis and McMullin (2002) theorized that individuals may experience greater intergenerational ambivalence when their ability to exercise agency is limited by social structural arrangements. An important question, therefore, for future research is this: How might socially and culturally constructed categories other than gender (e.g., race, ethnicity, class, age, sexual orientation, disability) influence parents’ experiences of ambivalence toward their adult children, and how might these statuses interact with gender?

Second, we examined intergenerational ambivalence from the perspective of older parents. Adult children of older parents may experience higher rates of intergenerational ambivalence (Fingerman et al., 2006; Willson et al., 2006), and how their experiences vary by gender it remains to be seen. Third, our analyses indicated that much of the variance explained in the model was at the level of the parent. It is possible that parent characteristics that were not measured in this study may provide additional explanatory power in future studies. For example, some parents may be more ambivalent in general, which is reflected in relationships with children. Adding measures of personality in studies of parental ambivalence would help shed light on this issue.

Despite these limitations, our findings shed new light on intergenerational ambivalence. Factors related to older parents’ feelings toward their adult children reveal a nuanced picture of intergenerational relationships and ambivalence, highlighting the importance of examining the perspectives of both mothers and fathers. In addition, the findings endorse the importance of including parental assessments of all children in the family when studying intergenerational ambivalence, as opposed to a single focal child. As a number of researchers have suggested (Kiecolt, Blieszner, & Salva, 2011; Willson et al., 2006), including multiple children allows analyses regarding parental differentiation among individual children as well as differences among gender pairs.

We recommend that future research expand the study of differences in mothers’ and fathers’ ambivalence regarding their adult children, addressing questions we have identified that were beyond the scope of the present study. Such efforts are particularly important given the role that ambivalence has been found to play in relationship quality and psychological well-being (e.g., Fingerman, Pitzer, Lefkowitz, Birditt, & Mroczek, 2008; Kiecolt et al., 2011; Suitor et al., 2011). Finally, the neglect of fathers in research on intergenerational ambivalence should be addressed in future studies. The findings presented here, that fathers reported higher levels of ambivalence and that predictors of ambivalence differ by gender, call for additional comparative study of both fathers and mothers.

Acknowledgments

Note This project was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG18869-01 and 2RO1 AG18869-04, J. Jill Suitor and Karl Pillemer, Co-Principal Investigators). Karl Pillemer also acknowledges support from Grant P30 AG022845 and an Edward R. Roybal Center grant from the National Institute on Aging (1 P50 AG11711-01). Jill Suitor also wishes to acknowledge support from the Center on Aging and the Life Course at Purdue University.

References

- Bengtson VL. Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Giarrusso R, Mabry JB, Silverstein M. Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: Complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:568–576. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00568.x. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Rosenthal C, Burton L. Families and aging: Diversity and heterogeneity. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1990. pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson J, Milkie M. Changing rhythms of American family life. Sage; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz TJ, Stacey J. How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:3–22. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00678.x. [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Fingerman KL, Zarit SH. Adult children’s problems and successes: Implications for intergenerational ambivalence. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2010;65B:145–153. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp125. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birditt KS, Miller LM, Fingerman KL, Lefkowitz ES. Tensions in the parent and adult child relationship: Links to solidarity and ambivalence. Psychology and Aging. 2009;24:287–295. doi: 10.1037/a0015196. doi:10.1037/a0015196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Maternal care and mental health. (Serial No. 2).World Health Organization Monograph. 1951 [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1958;39:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL, Dekovic M, Meeus W, van Aken MAG. Developmental patterns in adolescent attachment to mother, father and sibling. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:167–176. doi:10.1023/A:1015074701280. [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow N. The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow N. Feminism and psychoanalytic theory. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cohler BJ, Grunebaum H. Mothers, grandmothers, and daughters: Personality and childcare in three-generation families. Wiley; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane S. Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:208–233. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01208.x. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA, McMullin JA. Sociological ambivalence and family ties: A critical perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:558–567. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00558.x. [Google Scholar]

- Coser RL. Role distance, sociological ambivalence, and transitional status systems. American Journal of Sociology. 1966;72:173–187. doi: 10.1086/224276. doi:10.1086/224276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SN, Greenstein TN. Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology. 2009;35:7–105. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL. Aging mothers and their adult daughters: A study in mixed emotions. Springer; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Chen PC, Hay EL, Cichy KE, Lefkowitz ES. Ambivalent reactions in the parent and offspring relationship. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:P152–P160. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.3.p152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pitzer L, Lefkowitz ES, Birditt KS, Mroczek D. Ambivalent relationship qualities between adults and their parents: Implications for both parties’ well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63:P362–P371. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.p362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Role transitions in later life: A social stress perspective. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn EN. Social constructions of mothering: A thematic overview. In: Glenn EN, Chang G, Forcey LR, editors. Ideology, experience, and agency; Routledge; Mothering: New York: 1994. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hagestad GO. Towards a society for all ages: New thinking, new language, new conversations. Bulletin on Aging. 1998;2/3:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR, Machung A. The second shift. Viking; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH. Love and commitment. In: Kelley HH, Berscheid E, Christensen A, Harvey JH, Huston TL, Levinger G, McClintock E, Peplau LA, Peterson DR, editors. Close relationships. W. H. Freeman; New York: 1983. pp. 265–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt KJ, Blieszner R, Salva J. Long-term influences of intergenerational ambivalence on midlife parents’ psychological well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:369–382. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00812.x. [Google Scholar]

- Lettke F, Klein DM. Methodological issues in assessing ambivalences in intergenerational relations. In: Pillemer K, Lüscher K, editors. Contemporary perspectives in family research. Vol. 4. Intergenerational ambivalences: New perspectives on parent–child relations in later life. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2004. pp. 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- Liddon N, Leichliter JS, Habel MA, Aral SO. Divorce and sexual risk among US women: Findings from the National Survey of Family Growth. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19:1963–1967. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.1953. doi:10.1089=jwh.2010.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luescher K, Pillemer K. Intergenerational ambivalence: A new approach to the study of parent–child relations in later life. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher K. Conceptualizing and uncovering intergenerational ambivalence. In: Pillemer K, Lüscher K, editors. Intergenerational ambivalences: New perspectives on parent–child relations in later life. Elsevier/JAI Press; Amsterdam: 2004. pp. 23–62. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The gender of child and parent as factors in family dynamics. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh K, Darity WA, Cohen PN, Casper LM, Salters D. The emerging Black middle class: Single and living alone. Social Forces. 2007;86:735–762. doi:10.1093/sf/86.2.735. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon M. Engendering motherhood: Identity and self-transformation in women’s lives. Guilford Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Merton R, Barber E. Sociological ambivalence. In: Tiryalcian EA, editor. Sociological theory, values, and sociocultural change. Free Press; New York: 1963. pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Merz EM, Schuengel C, Schulze HJ. Intergenerational solidarity: An attachment perspective. Journal of Aging Studies. 2007;21:175–186. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2006.07.001. [Google Scholar]

- Peters CL, Hooker K, Zvonkovic AM. Older parents’ perceptions of ambivalence in relationships with their children. Family Relations. 2006;55:539–551. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00424.x. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K. Can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em: Older mothers’ ambivalence toward their adult children. In: Pillemer K, Lüscher K, editors. Contemporary perspectives in family research. Vol. 4. Intergenerational ambivalences: New perspectives on parent–child relations in later life. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2004. pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Explaining mothers’ ambivalence toward their adult children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:602–613. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00602.x. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Mock SE, Sabir M, Pardo TB, Sechrist J. Capturing the complexity of intergenerational relations: Exploring ambivalence within later-life families. Journal of Social Issues. 2007;63:775–791. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00536.x. [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport A, Lowenstein A. A possible innovative association between the concept of inter-generational ambivalence and the emotions of guilt and shame in care-giving. European Journal of Aging. 2007;4:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10433-007-0046-4. doi:10.1007/s10433-007-0046-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raulin ML. Development of a scale to measure intense ambivalence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52:63–72. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.52.1.63. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, White KL. Satisfaction with parenting: The role of marital happiness, family structure, and parents’ gender. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:293–308. doi:10.2307/353849. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi A. Intergenerational relations: Gender, norms, and behavior. In: Bengtson VL, Achenbaum WA, editors. The changing contract across generations. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1993. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of human bonding: Parent–child relations across the life course. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian N, Gerstel N. Till marriage do us part: Adult children’s relationships with their parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:360–376. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00487.x. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Bengtson V. Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child–parent relationships in American families. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;103:429–460. doi:10.1086/231213. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Giarrusso R. Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:1039–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00749.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sincoff JB. The psychological characteristics of ambivalent people. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:43–68. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(90)90106-K. [Google Scholar]

- Spitze G, Logan JR, Deane G, Zerger S. Adult children’s divorce and intergenerational relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:279–293. doi:10.2307/353100. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Gilligan M, Pillemer K. Conceptualizing and measuring intergenerational ambivalence in later life. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2011;66B:769–781. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr108. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Choosing daughters: Exploring why mothers favor adult daughters over sons. Sociological Perspectives. 2006;49:139–162. doi:10.1525/sop.2006.49.2.139. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Differences in mothers’ and fathers’ parental favoritism in later life: A within-family analysis. In: Silverstein M, Giarrusso R, editors. From generation to generation: Continuity and discontinuity in aging families. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Gilligan M, Pillemer K. Intergenerational relations in later-life families. In: Settersten R, Angel J, editors. Handbook of the sociology of aging. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet J, Bumpass L. The National Survey of Families and Households—Waves 1 and 2. Data Description and Documentation. Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin–Madison; 1996. Retrieved from http://ww.ssc.wisc.edu/nsfh/home.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Teo P, Graham E, Yeoh BSA, Levy S. Values, change and inter-generational ties between two generations of women in Singapore. Aging & Society. 2003;23:327–347. doi:10.1017/S0144686X0300120X. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MM, Zanna MP, Griffin DW. Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In: Petty RE, Krosnick JA, editors. Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1995. pp. 361–386. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:664–674. doi:10.2307/353252. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . American Community Survey: Table S0201. Selected Population Profile in the United States; 2006. Retrieved from http://hmongstudies.org/HmongACS1yearestimate2010US.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen RI, Dykstra PA. Solidarity and conflict between adult children and parents: A latent class analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:947–960. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00306.x. [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen RI, Dykstra PA, Komter AE. Where is the exit? Intergenerational ambivalence and relationship quality in high contact ties. Journal of Aging Studies. 2010;24:105–114. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2008.10.006. [Google Scholar]

- Ward RA. Multiple parent–adult child relations and well-being in middle and later life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63B:S239–S247. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RA, Spitze G, Deane G. The more the merrier? Multiple parent–adult child relations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:161–173. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00587.x. [Google Scholar]

- Webster MW, Rashotte LS. Fixed roles and situated actions. Sex Roles. 2009;61:325–337. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9606-8. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert AJ. Mixed emotions: Certain steps toward understanding ambivalence. State University of New York Press; Albany: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH. Ambivalence in the relationship of adult children to aging parents and in-laws. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:1055–1072. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.01055.x. [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH, Wickrama KAS. Ambivalence in mother–adult child relations: A dyadic analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2006;69:235–252. doi:10.1177/019027250606900302. [Google Scholar]