Introduction

Histones are small basic proteins that are core components of chromatin. As such, they are essential for cell viability and genomic stability and their levels are tightly controlled. In addition, histone tails are subject to extensive posttranslational modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitylation that play critical roles in many cellular processes. To quickly screen for alterations in histone levels and/or their modifications in yeast mutants under different growth conditions, we present a fast and reliable protocol for whole cell protein extract preparation and immunoblotting.

Related Information

The whole cell extract protocol was modified from Kushnirov (2000).

Materials

Reagents

S. cerevisiae strain(s) of interest

Nuclease-free water (Ambion, Austin, TX)

0.2 N sodium hydroxide solution (from 10-N stock)

β-mercaptoethanol

1× sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 10 % [v/v] glycerol, 2 % [w/v] SDS, 0.002 % [w/v] bromphenol blue)

Store in 1-ml aliquots at −20 °C. Just before use add β-mercaptoethanol to 5 % (v/v) final concentration.

For sodium carbonate transfer:

40× sodium carbonate transfer buffer, pH 9.5

| For 1 l: | 21.1 g NaHCO3 (251 mM), 18.35 g Na2CO3 (173 mM). |

| Mix in 0.9 l double distilled water (ddH20), pH to 9.5 with 10 N NaOH, add ddH20 to 1 l. Store at RT. |

For Tris-glycine transfer:

20× Tris-glycine transfer buffer

For 1 l: 24.2 g Tris base (200 mM), 150.1 g glycine (2 M).

Mix in 1 l double distilled water (ddH20). pH adjustment not necessary (will be ~8.8). Store at RT.

100 % methanol

Ponceau-S solution (0.5 % [w/v] Ponceau S, 1 % [v/v] glacial acetic acid)

Destaining solution (0.1 % [v/v] glacial acetic acid)

10 × TBS

| For 1 l: | 30 g Tris base (248 mM), 80 g NaCl (1.37 M), 2 g KCl (27 mM). |

| Mix in 0.9 l ddH20, pH to 7.4 with concentrated HCl, add ddH20 to 1 l. | |

| Store at RT. |

1× TBST (1× TBS, 0.1 % Tween 20)

Dry milk (e.g., CARNATION NonFat Dry Milk, Nestlé, Glendale, CA)

Primary antibody, e.g., anti-H3K4me3 (ab8580, Abcam, Cambridge, MA)

Secondary antibody, e.g., anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase(HRP)-linked (NA934V, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ)

Chemiluminescent substrate for detection of HRP conjugates (SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL)

Equipment

Chromatography paper (Grade 3MM Chr, Whatman)

Gel electrophoresis apparatus, room temperature

Polyvinyldifluoride (PVDF) transfer membrane (Immobilon P, pore size 0.45 µm, Millipore)

Millipore also offers Immobilon-PSQ membranes for proteins in the range of 10 – 20 kDa, in case Immobilon-P membranes do not yield optimal results

Amersham Hybond-P (GE Healthcare, pore size 0.45 µm) also yields good results

Electroblotting apparatus, room temperature

Clean container(s) for immunoblot

Plastic wrap (e.g., Saran Wrap)

Shakers, orbital or platform, room temperature

Darkroom and X-ray film developer

Method

Whole cell protein extracts from yeast and electrophoresis

-

1

Collect about 10 OD600 equivalents of cells (e.g., 20 ml of a culture at OD600 of 0.5) from a logarithmically growing liquid culture into 15-ml conical-bottom tube by spinning at 3,750 × g for 5 min at 4 °C.

-

2

Pour off supernatant and wash once with ice-cold ddH20.

-

3

Pour off supernatant, transfer pellet with rest of supernatant into 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and pellet by spinning at 20,800 × g for 10 s at 4 °C.

-

4

Pipette off supernatant.

This is to avoid loosing cells leading to uneven loading of gel.

Can freeze pellet in liquid nitrogen or on dry ice. Store at −70 °C. Thaw pellet on ice.

-

5

Resuspend cell pellet in 100 µl of ddH20, then add 300 µl of 0.2 M sodium hydroxide solution and 20 µl β-mercaptoethanol.

-

6

Incubate the sample for 10 min on ice.

-

7

Pellet the sample in a microcentrifuge at 20,800 × g for 10 min at 4 °C.

-

8

Resuspend the pellet in 100 µl of 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

-

9

Boil the sample for 10 min and pellet in a microcentrifuge at 10,600 × g for 3 min at room temperature.

-

10

Use 6 – 12 µl of the supernatant per lane of a 15 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel and resolve by electrophoresis (see “SDS-PAGE of proteins”).

Protein transfer to membrane

-

11

After electrophoresis, transfer proteins in a tank of buffer according to “Immunoblotting: Submerged Electrophoretic Transfer of Proteins from Gels to Membranes” with the following exceptions/notes:

-

12

Use PVDF membrane prepared as per manufacturer’s instructions - for Immobilon-P:

Soak in 100 % methanol for 15 s;

Wash in ddH20 for 2 min;

Equilibrate in transfer buffer for 5 min.

-

13Protein transfer conditions depend on transfer buffer used:

-

1× sodium carbonate transfer buffer, 20 % methanol for protein transfer.Transfer at 0.5 A (fixed) for 60 min at room temperature.Alternative transfer conditions might be possible (e.g., at 22 V [fixed], for 90 min at room temperature, see discussion).

-

1× Tris-glycine transfer buffer, 20 % methanol for protein transfer.Transfer at 0.2 A (fixed) for 60 min at 4 °C (cold room).

We found sodium carbonate buffer to give more consistent results compared to Trisglycine buffer.

-

Immunoblot for histone H3 methylated at lysine 4

-

14

After transfer, optionally stain/destain membranes with Ponceau-S/destaining solution.

-

15

Block membrane for 1 h in 5 % milk, 1× TBST on a platform shaker at room temperature.

-

16

Incubate membrane for 2 h with anti-H3K4me3, diluted 1:2,000 in 5 % milk, 1× TBST, on a platform shaker at room temperature.

-

17

Wash the membrane three times with 1× TBST for 5 min each on a platform shaker at room temperature.

-

18

Incubate membrane with anti-rabbit IgG, diluted 1:10,000 in 5 % milk, 1× TBST, for 30 min on a platform shaker at room temperature.

-

19

Wash the membrane three times with 1× TBST for 5 min each on a platform shaker at room temperature.

-

20

Develop membrane with chemiluminescent substrate as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Discussion

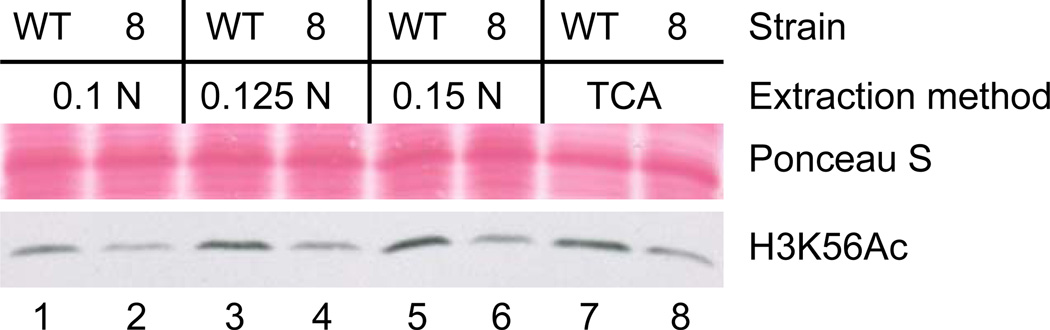

Several histone extraction methods have been previously described (Kizer et al. 2006; Shechter et al. 2007). While commonly histones were extracted from cells under acidic conditions (Davie et al. 1981; Edmondson et al. 1996), the alkaline extraction method described above was faster and allowed consistent and equal detection of a variety of histones and their modifications (Figure 1). The extracts were tested by immunoblotting with antibodies against histones H3, H4, H2B, mono-, di- and trimethylated histone H3K79, trimethylated histone H3K4 as well as acetylated histone H3K56. Increasing concentrations of NaOH improved transfer efficiency with 0.15N NaOH yielding the best results (Figure 1). Visualization of some other histone modifications such as H2BK123 ubiquitylation required different histone extraction methods that are amenable to scaling up the amounts of protein (Edmondson et al. 1996; Wood et al. 2003).

Figure 1.

Whole cell protein extracts were prepared from a wild-type (“WT”) yeast strain (genetic background: W303) or one containing a pol30-8 mutation (“8”). The pol30-8 mutation leads to reduced H3K56ac levels (Miller et al. 2008). Extract preparation was either with a final concentration of 0.1 N (see Kushnirov 2000), 0.125 N, 0.15 N NaOH or with TCA. After SDS-PAGE and protein transfer (sodium carbonate transfer buffer, 90 minutes, 22 V [constant], room temperature) the PVDF membrane was stained with Ponceau S and immunoblotted with an acetyl-histone H3K56 antibody (07-677, Millipore, Billerica, MA) as described.

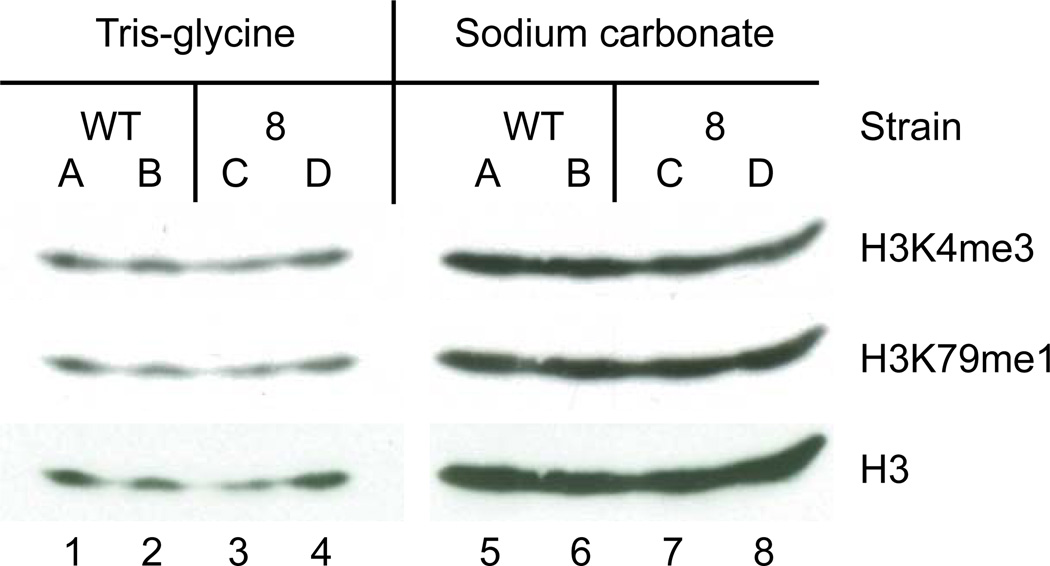

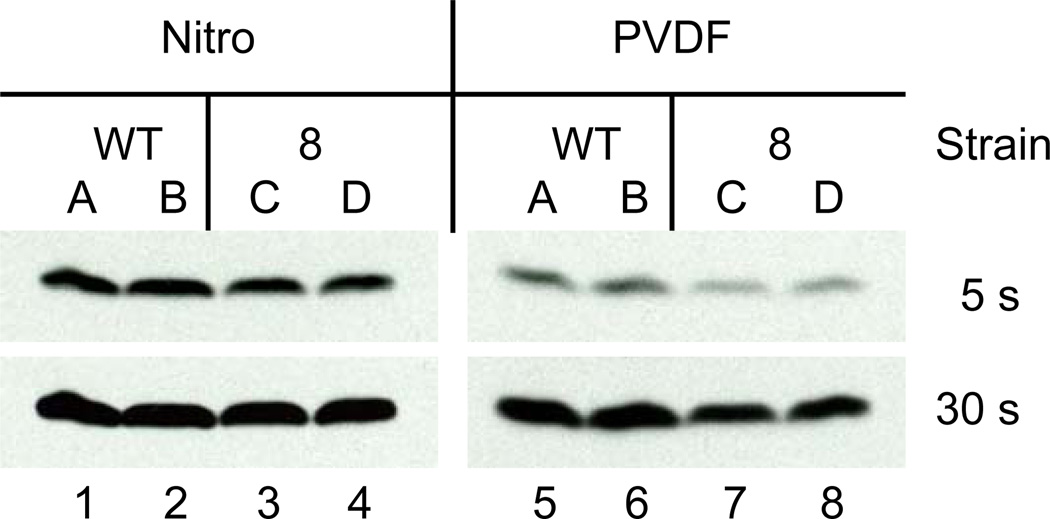

We found that histone transfer efficiency was overall higher with sodium carbonate buffer instead of the commonly used Tris-glycine buffer as revealed by immuno-blotting with Histone H3, H3K4 trimethyl and H3K79me specific antibodies (Figure 2, compare lanes 1 – 4 with 5 – 8). In comparison, Tris-glycine buffer was much more susceptible to transfer inconsistencies between identical samples (data not shown). In addition, sodium carbonate transfers were easier to set up as they worked best at room temperature (data not shown). Judging from Coomassie brilliant blue and amido black staining of gels and membranes, respectively, Szewczyk and Kozloff (1985) found an increase of transfer efficiency for small and strongly basic proteins including a histone mixture in ethanolamine/glycine, AMPSO or CAPSO buffers with pH 9.5 or 10. Using a sodium carbonate buffer Dunn (1986) observed good transfer efficiency for small subunits of the E. coli F1-ATPase in immunoblots, including non-basic subunits. For S. cerevisiae PCNA, a 29-kDa protein with an isoelectric point of 4.3, we obtained results that were similar to those described here for histones (data not shown). In the context of sodium carbonate transfer we found that PVDF membranes yielded more reproducible results for detecting even subtle differences in protein levels than did the use of nitrocellulose membranes (Figure 3, compare lanes 1 – 4 with 5 – 8). These subtle differences were further enhanced by lowering the voltage while increasing transfer time (Figures 1 and 3 and data not shown).

Figure 2.

Whole cell protein extracts prepared by alkaline lysis from two wild-type (“WT”) yeast strains (A + B) or two strains containing a pol30-8 mutation (“8”; C + D) were separated on a 15 % SDS-containing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was cut and one half transferred in Tris-glycine transfer buffer (left panel), while the other half was transferred in sodium carbonate transfer buffer (right panel) for 60 minutes at 4 °C and room temperature, respectively, both onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were sequentially immunoblotted with antibodies against tri methyl histone H3K4 (ab8580, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), mono methyl H3K79 (ab2886, Abcam) and total histone H3 (ab1791, Abcam) with stripping the membranes in-between (Re-Blot, Millipore). No protein transferring through the first onto a second membrane was detectable by Ponceau S staining (data not shown). Lanes 1 and 5 (“WT” A), 2 and 6 (“WT” B), 3 and 7 (“8” A) as well as 4 and 8 (“8” B) contain identical samples.

Figure 3.

Whole cell protein extracts prepared by alkaline lysis from two wild-type (“WT”) yeast strains (A + B) or two strains containing a pol30-8 mutation (“8”; C + D) were separated on a 15 % SDS-containing polyacrylamide gel and transferred for 90 minutes at 22 V (constant) onto nitrocellulose (“Nitro”) or PVDF (“PVDF”) membranes using sodium carbonate buffer at room temperature. After SDS-PAGE and protein transfer the PVDF membrane was stained with Ponceau S and immunoblotted with an acetyl-histone H3K56 antibody as in Figure 1. Lanes 1 and 5 (“WT” A), 2 and 6 (“WT” B), 3 and 7 (“8” A) as well as 4 and 8 (“8” B) contain identical samples.

Together, we found a combination of alkaline extraction and transfer in sodium carbonate buffer onto PVDF membranes to be the most efficient and sensitive method for the comparative detection of many histone modifications and their levels.

References

- Davie JR, Saunders CA, Walsh JM, Weber SC. Histone modifications in the yeast S. Cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:3205–3216. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn SD. Effects of the modification of transfer buffer composition and the renaturation of proteins in gels on the recognition of proteins on Western blots by monoclonal antibodies. Anal Biochem. 1986;157:144–153. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson DG, Smith MM, Roth SY. Repression domain of the yeast global repressor Tup1 interacts directly with histones H3 and H4. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1247–1259. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizer KO, Xiao T, Strahl BD. Accelerated nuclei preparation and methods for analysis of histone modifications in yeast. Methods. 2006;40:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnirov VV. Rapid and reliable protein extraction from yeast. Yeast. 2000;16:857–860. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000630)16:9<857::AID-YEA561>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A, Yang B, Foster T, Kirchmaier AL. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen and ASF1 modulate silent chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via lysine 56 on histone H3. Genetics. 2008;179:793–809. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.084525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter D, Dormann HL, Allis CD, Hake SB. Extraction, purification and analysis of histones. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1445–1457. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk B, Kozloff LM. A method for the efficient blotting of strongly basic proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:403–407. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A, Schneider J, Dover J, Johnston M, Shilatifard A. The Paf1 complex is essential for histone monoubiquitination by the Rad6-Bre1 complex, which signals for histone methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34739–34742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]