Abstract

Efforts are underway for early-phase trials of candidate therapies for cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), an untreatable cause of hemorrhagic stroke and vascular cognitive impairment. A major barrier to these trials is the lack of consensus on measuring treatment effectiveness. We review a range of potential outcome markers for CAA against the ideal criteria of being clinically meaningful, closely reflective of biological progression, efficient for smaller/shorter trials, reliably measurable, and cost effective. In practice, outcomes tend either to have high clinical salience but relatively low statistical efficiency and thus more applicability for later phase studies, or greater statistical efficiency but more limited clinical meaning. The most statistically efficient outcomes are those that are potentially reversible with treatment, though their clinical significance remains unproven. Many of the candidate outcomes for CAA trials are likely to be applicable to other small vessel brain diseases as well. Considerations emerging from this review outline a path towards rapid and efficient testing of emerging candidate therapies for CAA and other small vessel diseases.

Cerebrovascular deposition of amyloid (cerebral amyloid angiopathy, CAA) represents a major cause of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in the elderly as well as an important contributor to age-related cognitive decline.1 CAA is increasingly diagnosed during life by pathological sample or neuroimaging detection of multiple strictly lobar hemorrhagic lesions according to the validated Boston criteria.2 There are multiple plausible approaches to preventing or treating CAA (such as inhibiting ß-amyloid peptide [Aß] production, enhancing its clearance, or protecting vessels from its toxic effects) and a recently initiated phase 2 monoclonal antibody study,3 but as of yet no large-scale clinical trials.

A barrier to CAA trials is the lack of consensus regarding outcome markers for determining treatment effectiveness. An ideal CAA marker would be one that is clinically meaningful, closely reflective of the disease's underlying biological progression, efficient at detecting changes response to treatment, reliably and reproducibly measurable, and easily generalizable across multiple trial sites. In practice, no single marker will have all these desired features, resulting in tradeoffs between efficient surrogate markers useful for early-phase studies aimed at identifying promising candidate treatments versus clinically meaningful markers for pivotal studies to establish those treatments for medical use.

This manuscript, which emerged from proceedings of the International CAA Conference held in Leiden, the Netherlands 24-26 October 2012, reviews potential markers for clinical CAA trials based on current understanding of the disease's underlying biology and neurological impact. Emerging data suggest that advanced CAA can be measured by a wide range of markers, including clinical events (e.g. symptomatic ICH, cognitive decline), structural brain lesions (e.g. microbleeds, white matter hyperintensities, microinfarcts), alterations of vascular physiology, and direct visualization with amyloid radioligands. Each comes with particular drawbacks, such as the nonspecificity of structural brain lesions for CAA (versus other small vessel diseases) or of amyloid radio ligands for vascular Aß (versus senile plaques). Rapidly accumulating data on in vivo detection of the pathogenic steps involved in CAA nonetheless offers substantial promise for future trials aimed at identifying disease-modifying therapies for this largely untreatable disease.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

References for this Review were identified by searches of Pub Med between 1969 and December, 2013, and references from relevant articles. The search terms “amyloid angiopathy,” “congophilic angiopathy,” “CAA,” “intracranial h(a)emorrhage,” “intracerebral h(a)emorrhage,” “cerebral/brain microbleed/microh(a)emorrhage,” “cerebral/cortical/brain microinfarct,” as well as a broader search strategy for ICH studies4 were used. References were also identified from the bibliography of identified articles and the authors' files. Only papers published in English or with available English translations of relevant data were reviewed. The final reference list was generated on the basis of relevance to the topics covered in this Review.

Candidate Outcome Markers

A summary of candidate outcome markers for CAA and the authors' consensus ratings of their properties are provided in Table 1. International consensus standards for describing, analyzing and reporting many of the lesion types described below have been recently published5 and should facilitate cross-study comparisons and enhance generalizability of findings.

Table 1. Overview of Outcome Markers for Human Studies in CAA.

| Outcome Marker | Link to Clinical Function | Measure of CAA Severity/Progression | Statistical Efficiency for Smaller/Shorter Studies | Reproducibility Across Sites | Cost Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic ICH | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| Microbleeds | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| WMH | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Microinfarcts | ++ | ? | ++ | ? | + |

| DTI Changes | ++ | ? | ++ | ? | + |

| Cognitive Testing | +++ | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| Amyloid Imaging | ? | +++ | +++ | ++ | + |

| Vascular Reactivity | ? | ++ | +++ | ? | + |

| CSF Amyloid | ? | ? | +++ | +++ | + |

+ = Low ++ = Moderate +++ = High ? = Unknown

Ratings represent the authors' consensus based on the literature cited in the corresponding sections of the text.

ICH = Intracerebral hemorrhage WMH = White matter hyperintensities DTI = Diffusion-tensor imaging CSF = Cerebrospinal fluid

Hemorrhagic Markers

Symptomatic ICH is an appealing outcome for clinical trials because of its relationship to underlying CAA severity and pathophysiology,6 apparent ease of detection, and importance to patients. ICH is a relatively rare event, however.7 It is somewhat more common in selected groups such as individuals with multiple microbleeds,8, 9and most common as a recurrent event in survivors of lobar ICH, with incidence estimates ranging from 2.5% to 14.3% per year.4 Although detection of “macroscopic” ICH by CT scan is technically straightforward, it should be noted that the presentation of ICH may also be too mild or nonspecific to trigger a timely CT scan, or alternatively may be rapidly fatal precluding brain imaging.

These caveats notwithstanding, symptomatic ICH remains a reliable and clinically meaningful trial outcome given the high burden of disability associated with lobar ICH.10 Its major limitation is efficiency, as even recurrent lobar ICH occurs infrequently enough to require large sample sizes and long durations of follow-up. Under the optimistic assumptions that a treatment would reduce annual recurrence from 10% to 5% (i.e. relative risk reduction of 50%), a randomized controlled trial with one year follow-up would be estimated to require 862 CAA subjects with prior ICH to achieve 80% statistical power and 1154 subjects for 90% power. A more conservative scenario in which annual recurrence was reduced from 10% to 8% would require 6420 subjects to achieve 80% power. Restricting to CAA patients deemed at higher risk for ICH recurrence because of microbleed counts11 or apolipoprotein E genotype12 would reduce the required sample size, but also reduce the number of available study subjects. These sample size estimates suggest that ICH would be most suitable for late- rather than early-phase trials.

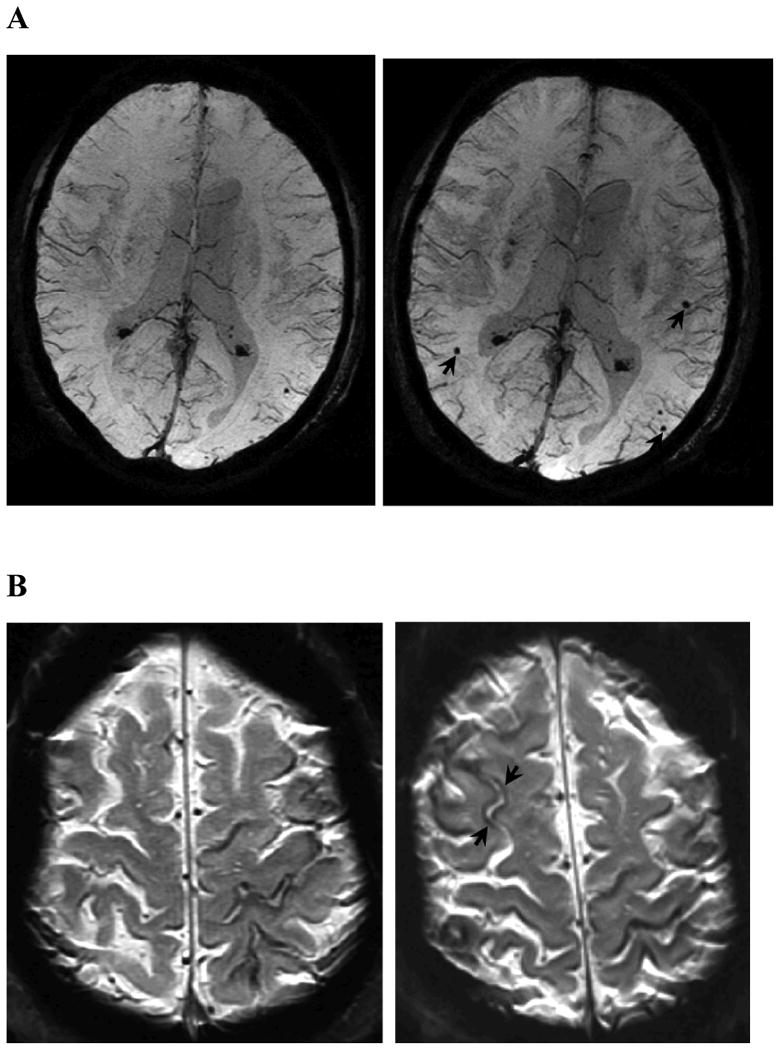

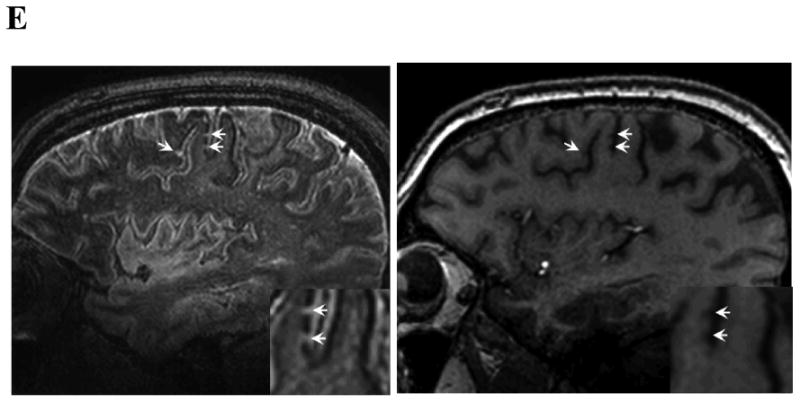

Cerebral microbleeds13 (CMB) represent an alternative hemorrhagic marker of CAA. Their primary advantage as an outcome marker relative to symptomatic ICH is substantially higher prevalence and incidence. Strictly lobar CMB appear to be indicative of CAA-related vasculopathy, but also frequently occur among presumably healthy persons, possibly a result of clinically silent CAA pathology.14, 15 Appearance of new lobar CMB (Fig. 1A) has been reported in 6.1% of 831 older individuals in the general population rescanned after a mean 3.4 years,15 17.5% of the subset with one or more strictly lobar microbleeds at baseline,15 and in 50%of 34 probable CAA-ICH patients (median of 3 new microbleeds in positive subjects) rescanned after mean 15.8 months.11 Although more data are required to estimate sample sizes accurately, the greater incidence of new CMB relative to symptomatic ICH (in terms of both the proportion of subjects affected and the numerical count of incident lesions) offers substantial efficiencies in demonstrating any given relative reduction in incident events.

Figure 1.

Examples of MRI markers. Panels A shows a 74 year old man with a total of 6 strictly lobar microbleeds on baseline T2*-weighted MRI (left-hand panel shows 1 of these) and 5 incident strictly lobar microbleeds on follow-up performed 3.4 years later (right-hand panel shows 3 of the incident lesions, arrows). Panels B show superficial siderosis on T2*-weighted MRI in a 69 year old man with probable CAA and predominantly left hemispheric siderosis at baseline (left) and incident right superior frontal siderosis on follow-up 1.5 years later (right, arrows). Panels C show growth of WMH on FLAIR images between baseline (left) and follow-up at 5 years (right) in an 89 year old man with probable CAA, old right occipital ICH, and progressive impairment of executive function but no ICH during the inter-scan interval. WMH volumes in the left (non-ICH) hemisphere were 18.5 cc at baseline and 23.9 cc at follow-up. Panels D shows a left frontal cortex focus of restricted diffusion (DWI image on left, absolute diffusion coefficient map on right) consistent with a small acute infarct in a 74 year old man with probable CAA and no other known vascular disease. Panel E shows sagittal FLAIR (left) and T1 (right) images obtained by 7T MRI58 of a 62 year old man with mild cognitive impairment. The lesions suggestive of cortical microinfacrts appear hyperintense on FLAIR and hypointense on T1 (arrows and insets for enlargement).

The major drawbacks of CMB as study outcome are their somewhat limited relevance as a clinically meaningful outcome, their imperfect specificity for CAA, and technical issues in their detection. These lesions clearly have less impact on neurologic function than symptomatic ICH, though the presence of many (5 or more) strictly lobar CMB in the general elderly16 or any strictly lobar CMB in ischemic stroke patients17 have been independently linked to detectable cognitive dysfunction. CMB also have clinical impact as markers of increased risk of future symptomatic ICH.11, 18 CMB are not specific for CAA,19 but the pattern of lesions restricted to lobar brain regions appears to associate with genetic risk factors for sporadic14, 15, 20 or familial21 CAA suggesting that this distribution might be sufficiently specific to be used as an outcome measure. Finally, variations in CMB detection across different MRI sequence parameters,22 field strengths,23 and raters24-26 demonstrate the need for standardized methods in applying this marker across centers, as in the ongoing multicenter RESTART and CROMIS-2 studies. Microbleeds thus appear best suited to serve as an early phase marker of therapies aimed at reducing CAA-related hemorrhagic events, but require careful methods for standardized detection and interpretation.

Recent data have implicated acute or chronic hemorrhage within or adjacent to the cortical sulci (often described as superficial siderosis when chronic or convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage when acute) as another form of CAA-associated bleeding. Superficial siderosis is common in CAA (23 of 38 neuropathologically examined brains versus 0 of 22 brains with non-CAA related ICH27), often distant from sites of lobar hemorrhage27-29 suggesting that it is a separate CAA-related bleeding event. Siderosis may also have clinical meaning in CAA as a trigger of transient focal neurological symptoms28 and a possible marker of increased risk for future ICH.30, 31 Progression of superficial siderosis (Fig 1B) presumably represents a new bleeding event and thus a candidate CAA marker, but has not yet been systematically studied or measured by standardized methods.

Nonhemorrhagic Markers

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) of presumed vascular origin, visualized on T2-weighted or FLAIR MRI sequences, are a ubiquitous phenomenon of aging, but occur at much greater volume in individuals diagnosed with CAA than in healthy aging or Alzheimer disease (AD)/mild cognitive impairment.32 Although the precise pathophysiology of WMH remains ill-defined (and may indeed be heterogeneous), a vascular basis is suggested by its association with cerebral small vessel diseases such as CAA and with vascular risk factors. WMH volume can be assessed visually using ordinal rating scales or by volumetric methods, usually semi-automated. WMH progression between scans (Fig. 1C) can be measured by qualitative scales33 or quantitative methods.34 A study in 26 patients (mean age 69.1) with probable or possible CAA scanned 1-2 years apart found median WMH growth of 0.5 mL per year (interquartile range 0.1-2.8 mL per year),35 a rapid pace of progression relative to population-based estimates in normal aging subjects36 and similar to that in the subset of individuals with baseline early confluent or confluent WMH in the population-based Austrian Stroke Prevention Study.37

The association between WMH and pre-stroke cognitive impairment in CAA,38 and with multiple markers of cognitive impairment, disability, and future decline in non-CAA subjects39-43 suggest that WMH may measure a clinically meaningful aspect of small vessel-related brain injury. Larger follow-up studies in CAA have not yet been done to link longitudinal change in WMH with longitudinal decline in cognitive testing or conversion to dementia, however. The feasibility of measuring WMH progression in multicenter studies has been demonstrated by its incorporation in a range of reported randomized controlled trials,44-48 supporting its feasibility. The reliability of volumetric methods for measuring WMH progression appears to be high,49 but it is largely unknown if reliability is affected by inter-site variables such as scanner manufacturer, field strength, sequence type (e.g. T2-weighted vs. FLAIR), or scan resolution. The variability introduced by these factors might be mitigated by harmonization of scanning parameters (particularly voxel size) across sites, use of the same scanner/sequence at baseline and follow-up, and a within-subject analysis design. As nearly all CAA subjects appear to show at least some WMH growth over 1-2 years,35 WMH may have equal or greater ability as CMB count to detect treatment effects. Data from the single published study on WMH progression in CAA indicate that 238 subjects (119 per arm) would be needed to detect a 50% reduction in WMH progression with 80% power, or fewer subjects if trials are restricted to those with more extensive baseline WMH. WMH progression thus appears to represent another promising outcome marker for early phase trials as well as a reasonably well-validated marker for cognitive disability. Its major limitations are its lack of specificity for CAA, the relatively loose connection between WMH and CAA's hemorrhagic manifestations (raising the possibility that agents that block WMH progression might not also block bleeding), and the cost/labor required for serial MRI scans and volumetric measurements.

Microinfarcts, defined as areas of infarction not visible by eye but seen on histopathological examination (i.e. up to about 1 to 2 millimeters)50 have long been noted in association with advanced CAA51, 52 Although individually tiny, accumulating evidence indicates that these lesions may collectively have important independent effects on cognition.50, 53 Substantial efforts have focused on visualizing microinfarcts in vivo, a prerequisite for considering these lesions as potential outcome markers. Two emerging candidate approaches are detection of clinically silent foci of restricted diffusion by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI)54-57 and structural imaging of the mature lesions with ultrahigh field MRI.58 DWI lesions (Fig. 1D), typically several millimeters in diameter on MRI, are postulated (still without neuropathological confirmation) to represent acute microinfarcts at the large end of the microinfarct size spectrum. Such lesions have been reported in approximately 10-20% of CAA patients imaged either at the time of ICH or in the chronic post-ICH period, suggesting they may represent a marker of ongoing CAA-related brain injury. More recently, structural imaging at 7 Tesla has revealed small FLAIR hyperintense and T1 hypointense lesions (Fig. 1E) with post-mortem MRI-histopathologic correlation confirming this appearance as bona fide microinfarcts.58 A key limitation of both approaches is their ability to detect lesions only at the upper limit of microinfarct size, leaving the majority of microinfarcts (with an estimated mean diameter of approximately 0.3 mm59) invisible to current neuroimaging. Other remaining challenges are the still undefined relationship between the DWI and 7T FLAIR lesions, the temporal limitations of DWI (hyperintensities are typically visible only 1-2 weeks following infarction), and the generalizability of either method across centers. The clinical impact of microinfarcts on cognitive function and future hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke risk in CAA patients also remains to be determined. Current data suggest that both the overall lesion burden59 and incidence of new lesions54, 55 is much greater for microinfarcts than cerebral microbleeds, highlighting their potential for extremely high statistical efficiency as an outcome if they could be sensitively detected.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) obtained from multidirectional MRI diffusion gradients allows measurement of the amount (mean diffusivity, MD) and directional bias (fractional anisotropy, FA) of water diffusion throughout the brain. A small study of 11 participants with CAA-related ICH and 13 matched healthy controls found reduced FA in the temporal white matter (inferior longitudinal and occipital fasciculi, 17% reduction) and splenium of the corpus callosum (15% reduction) as well as increased FA of lower magnitude in deep grey matter structures.60 The changes were bilateral and did not appear to be influenced by the hemisphere of cerebral hemorrhage. Another study of global MD in 49 CAA subjects found higher values among those with pre-ICH cognitive impairment compared to those without.61 These data suggest that white matter microstructure is abnormal in CAA and can be measured using DTI. They require further validation, however, in particular to determine whether clinically relevant changes can be detected over time as has been suggested for other small vessel disease.62 Standardized DTI appears to be feasible across scanners and sites. Standardized DTI across scanners and sites has not been extensively studied, but may be feasible.63 Other techniques developed to probe the microstructure of cerebral white matter, such as magnetization transfer imaging, MR spectroscopy, and quantitative mapping of MR parameters (e.g. proton density, T1, T2, T2*), have yet to be applied or validated in the context of CAA, but hold promise based on reports in aging or ischemic small vessel disease.64

Enlarged perivascular spaces (PVS, also termed Virchow-Robin spaces), the potential spaces surrounding small parenchymal blood vessels, represent another candidate nonhemorrhagic marker visible on MRI. Enlarged or dilated PVS, presumed to reflect the accumulation of interstitial fluid, have been linked to the presence and severity of cerebral small vessel disease.65, 66 CAA appears to be preferentially associated with high numbers of visible PVS in the centrum semiovale,67, 68 consistent with the known localization of CAA to the superficial cortical vessels. As with other emerging markers, enlarged PVS will require analysis for incident appearance over time, standardization across sites, and correlation with clinical status for it to be evaluated as a potential outcome marker.

Cognitive Performance

Along with symptomatic ICH, cognitive decline is the most clinically salient manifestation of CAA. Multiple studies have demonstrated the association of CAA and cognitive impairment across cohorts, institutions, and countries.69-75 In the Religious Orders Study, individuals with moderate-to-very severe CAA pathology at autopsy (representing 18.9% of the 404 study subjects) demonstrated worse perceptual speed and episodic memory than those with no-to-minimal CAA, remaining independent of AD pathology, cerebral infarcts, Lewy bodies, age at death, sex, and education in multivariable analysis.75 The precise mechanism by which advanced CAA gives rise to cognitive impairment remains undefined, and could represent the cumulative effects of the various hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic tissue injuries discussed above as well as contribution from coexistent AD pathology. Vascular amyloid itself may also trigger reactive changes and neuronal degeneration in surrounding tissue.76

Prevention of cognitive decline, like prevention of symptomatic ICH, represents a clinically meaningful outcome appropriate for late-phase trials, though is relatively inefficient for early-phase studies. One theoretical advantage of cognition as an outcome is that it might be sensitive to cumulative changes across multiple hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic lesion types, potentially demonstrating the sum of treatment effects too small to be detected individually. Cognitive testing also has the advantages of utilizing tools that are well accepted by academia and industry (though primarily developed for AD rather than vascular cognitive impairment), validated across examiners and institutions, cost effective, relatively time efficient, quantitative, and measurable longitudinally. These advantages are offset by the nonspecificity of any cognitive test battery for CAA and the absence thus far of a sensitive and specific cognitive profile to discriminate CAA from other age-related conditions, as episodic memory and perceptual speed75 overlap with domains affected in AD and other common dementias. Moreover, The absence of a clear link between cognitive performance and any single CAA-related injury type also limits the ability of these measures to provide specific pathophysiologic information on the biological effects of candidate treatments. Finally, CAA-related cognitive impairment likely represents largely irreversible brain injury and thus requires trials of sufficient size and duration for substantial progression to occur in untreated subjects. No information is yet available on rate of cognitive decline in CAA.

Vascular pathology and physiology

The hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic structural lesions and cognitive measures considered above are believed to reflect vascular-mediated injury to the brain rather than abnormalities of the vessels themselves. They may thus measure relatively late and irreversible steps in the postulated pathways leading from vascular dysfunction to brain injury and clinical dysfunction. An effective therapy might prevent future changes in these markers, but studies to detect this effect need to be large and long enough for sufficient new injuries to occur in the untreated subjects. Direct markers of vessel pathology and physiology, conversely, might not only be blocked from worsening, but also actually improved by an effective treatment. A marker that is reversible might provide the highest level of statistical efficiency, allowing the possibility of smaller/shorter studies of candidate therapies.

Vascular amyloid can be detected and quantified by PET scanning with the amyloid radiioligand [11C]-Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB). Although this agent was initially developed to detect senile plaque Aß in AD, multiple studies have demonstrated increases in both global and occipital lobe PiB retention in nondemented sporadic77, 78 and familial79 CAA subjects and at foci of past80 and future81 CAA-related hemorrhagic lesions. Higher PiB retention is also independently associated with greater WMH burden in CAA but not AD or healthy elderly subjects,32 suggesting a link with CAA-related nonhemorrhagic as well as hemorrhagic brain injury.

Amyloid load could potentially serve as an outcome marker for early-phase studies aimed at reversing or preventing vascular amyloid deposition. This approach has been used in conjunction with anti-amyloid antibody infusion to demonstrate reduction of PiB retention in AD subjects82 and clearance of CAA in a transgenic mouse model.83 It is unknown, however, whether reduction of vascular amyloid burden in CAA patients will have beneficial clinical effects; such benefits have not yet been demonstrated with amyloid clearance in AD.84 Among other hurdles to be overcome in applying amyloid imaging to CAA trials are the specialized facilities and high cost required for production of radiolabeled amyloid ligands, the nonspecificity of current agents for vascular versus plaque amyloid, and the absence of natural history data on rate of vascular amyloid progression. Fluorine-18-tagged amyloid ligands such as florbetapir F 18,85 longer-lived and therefore less expensive and logistically demanding than carbon-11 compounds, have been developed for AD, though not yet tested in CAA. It is also notable that methods for performing and analyzing PiB-PET across multiple sites have been developed by the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative86 and other multicenter collaborations.

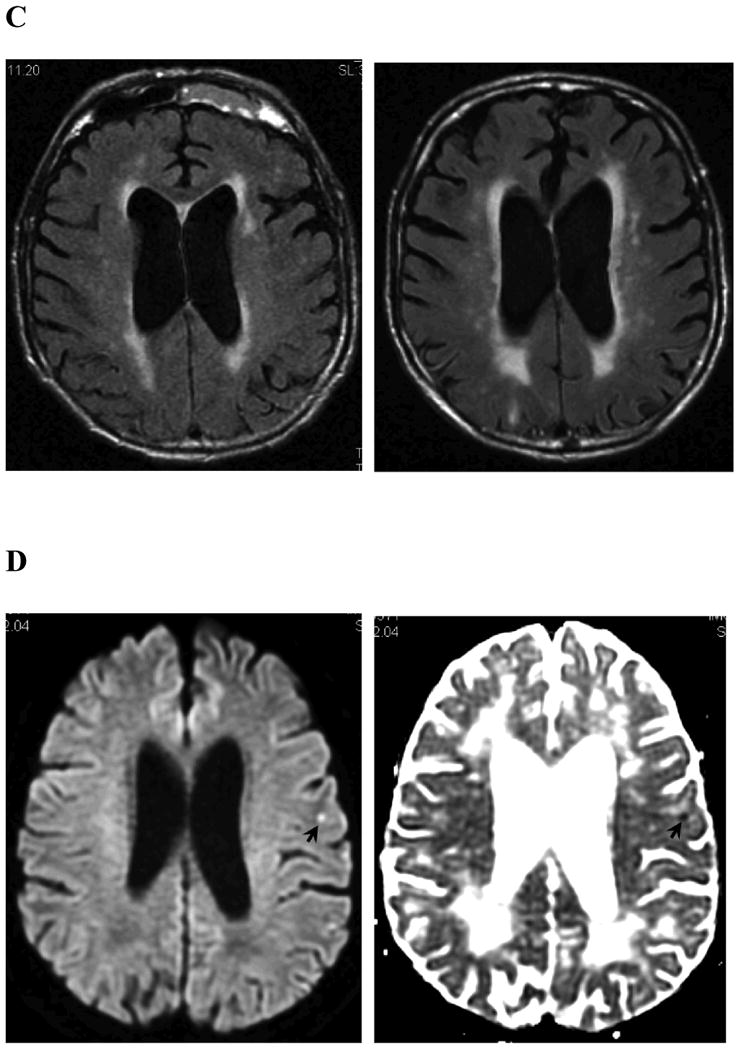

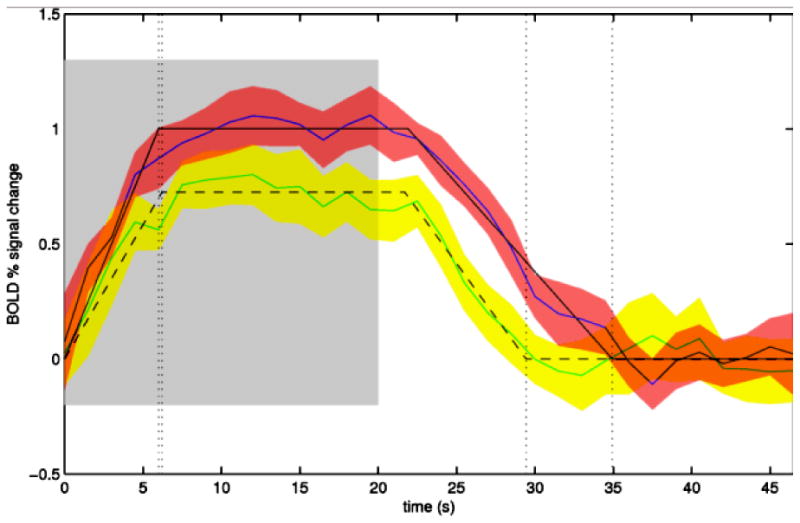

CAA is also associated with altered vascular reactivity to physiologic stimulation. Studies measuring the functional MRI (fMRI) blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) response to visual stimulation (Fig. 2) found that CAA subjects had27 to 28% reduced peak amplitude,87, 88 73% longer time till peak and 42% longer time till return to baseline87 relative to similar aged control subjects. Altered BOLD response might represent either vascular or neuronal dysfunction, but the observations that CAA and control subjects had similar visual evoked response potentials88 and that similar results could be obtained in analyses restricted to responding voxels only87 argue that the differences are due to the effects of CAA on the vessels themselves. The fMRI response to visual stimulation appears to correlate with markers of CAA severity such as microbleed count and WMH volume,87, 88 suggesting that these parameters might reflect the underlying extent of disease and a potentially important mechanism for its pathogenesis. Like vascular amyloid deposition, impaired vascular reactivity has been demonstrated in transgenic mouse models to be at least partly reversible,89, 90 raising the possibility that BOLD fMRI might serve as an efficient marker for trials aimed at reducing amyloid's effects on vessel physiology. The reproducibility of this approach across multiple time points and multiple study sites remains to be determined, however.

Figure 2.

Serial functional MRI measurement of response to visual stimulation. Exemplar fMRI studies are shown from a 83 year old woman with probable CAA. fMRI with visual stimulation was performed at baseline (blue line, red error space) and again using the same scanner and protocol after 1 clinically asymptomatic year (green line, yellow error space). The blue and green solid lines represent the change from baseline BOLD signal averaged over 16 cycles of visual stimulation (on 20 sec, shaded region, then off 28 sec), with standard deviations of the response shown in red and yellow spaces and the trapezoidal model fits in solid and dashed black lines as described.87 The amplitude of the modeled peak response in this subject decreased from 1.06% at baseline to 0.80% at 1 year.

Circulating Biomarkers

Biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or plasma offer another approach for measuring underlying, potentially reversible aspects of CAA pathogenesis. Two studies of CSF from patients diagnosed with CAA found reductions of the ß-amyloid peptide Aß40 and Aß42 species, with phospho- and total tau concentrations above those in elderly controls but lower than in AD.91, 92 These findings are broadly consistent with the pathology of CAA, which entails vascular deposition of Aß40 as well as Aß42 and inconsistent coexistence of tau-containing lesions. The association between CSF Aß and CAA disease progression has yet to be explored; by analogy to AD,93 one might expect the reductions in CSF Aß in CAA to correlate inversely with, and carry roughly the same information as, amyloid burden in CAA measured by PiB-PET.

A recent study of plasma Aß reported elevated Aß40 and Aß42 concentrations in probable CAA relative to healthy controls,94 differences not seen in an earlier analysis.95 Another candidate family of molecules, the matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9, have been found to be highly expressed near CAA-related ICH, but are not elevated in plasma of CAA patients.96 These circulating biomarker studies are substantially limited by the very small number of CAA subjects examined (fewer than 100 published across all studies to date) and absence of data on reproducibility across sites or longitudinal change with disease progression.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Several lessons and plans for future studies can be drawn from this overview of outcome markers for CAA trials (see Table 1). Markers now exist for most of the postulated steps in CAA pathogenesis, ranging from vascular amyloid deposition itself to physiologic alterations, hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic structural damage, symptomatic hemorrhagic stroke, and cognitive dysfunction. It is thus possible to consider pilot trials for CAA in which one or more of these markers is used to demonstrate a particular biological activity of a candidate therapy, such as use of PiB-PET to demonstrate partial clearance of plaques in the phase 2 AD study of bapineuzumab.82 Such pilot trials might be particularly efficient when using potentially reversible markers like amyloid imaging and vascular reactivity. None of the imaging biomarkers has yet been linked closely enough to neurologic impairment, however, to serve as a true surrogate marker of clinically meaningful treatment effects. Symptomatic ICH and cognitive testing thus remain the only reasonably valid outcomes for studies aimed at demonstrating true clinical benefit.

Although the pathogenic mechanisms and data reviewed here focus specifically on CAA, many of the considerations and findings can be generalized to all forms of cerebral small vessel disease associated with vascular cognitive impairment (VCI). Despite increasing understanding of the biology of these small vessel processes, there are few established treatments for VCI prevention; control of hypertension was the only class I recommendation for patients at risk for VCI in a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.97 Trials to establish specific therapies for common age-related small vessel pathologies, like those for CAA, would be greatly facilitated by study outcomes that are clinically and biologically meaningful, statistically efficient, and generalizable across sites. Nearly all of the measures of tissue injury and altered physiology described above are observed as well in arteriolosclerosis or chronic hypertensive vasculopathy,14, 56, 98-100 suggesting that these markers may represent general features of damage to the small cerebral vessels. No in vivo methods have yet emerged to measure arteriolosclerosis pathology in an analogous fashion to PiB detection of CAA, however, highlighting the importance of achieving further progress in molecular imaging of small vessel diseases.

Data that strengthen the links between imaging biomarkers and neurologic function would allow greater reliance on these more efficient surrogate markers of clinical outcome in future trials. Based on current data, WMH volume appears to have the closest demonstrated correlation to cognition and microbleeds the closest correlation to symptomatic ICH, but improving imaging modalities and larger study populations may provide stronger support for other neuroimaging markers or combinations of markers. Other key areas of need are determination of the rates of biomarker progression over time and validation of imaging methods across sites, both prerequisites for the ultimate goal of multicenter biomarker-based interventional trials. Further growth in the armamentarium of trial outcome markers, together with improved mechanistic understanding of small vessel degeneration, will provide a strong foundation for identifying successful disease-modifying therapies for CAA and related diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susanne van Veluw, M. Edip Gurol, and Panos Fotiadis for assistance with figures. Dr. Greenberg is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 AG26484, R01 NS070834). Dr. Al-Shahi Salman is funded by a MRC senior clinical fellowship. Dr. Biessels is funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw Vidi grant 91711384) and the Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant 2010T073). Dr. Lee is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS067905). Dr. Vernooij is funded by an Erasmus MC Clinical Fellowship. Dr. Werring's center receives funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme.

Role of the Funding Source: No external funding was received for this manuscript. All authors had full access to the manuscript and approved its contents.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the literature search, drafting of the manuscript, and critical review process.

Conflicts of Interest: Massachusetts General Hospital, University of Calgary, Washington University/Barnes Jewish Hospital, Leiden University Medical Center, and Lille University Hospital have clinical research support agreements with Pfizer, sponsor of an ongoing trial for CAA. Dr. Schneider has received consulting fees or sat on paid advisory boards related to amyloid imaging for AVID radiopharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly Inc., and GE Healthcare. No other authors had conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Viswanathan A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(6):871–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.22516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudsen KA, Rosand J, Karluk D, Greenberg SM. Clinical diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Validation of the Boston Criteria. Neurology. 2001;56(4):537–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfizer. Study evaluating the safety, tolerability and efficacy of PF-04360365 in adults with probable cerebral amyloid angiopathy. ClinicalTrialsgov. 2013: NCT01821118. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01821118?term=ponezumab&rank=5.

- 4.Poon MT, Fonville AF, Al-Shahi Salman R. Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2013 Nov 21; doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306476. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822–38. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Ropper AH, Bird ED, Richardson EP. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy without and with cerebral hemorrhages: a comparative histological study. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(5):637–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(2):167–76. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SH, Ryu WS, Roh JK. Cerebral microbleeds are a risk factor for warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2009;72(2):171–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339060.11702.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charidimou A, Kakar P, Fox Z, Werring DJ. Cerebral microbleeds and recurrent stroke risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack cohorts. Stroke. 2013;44(4):995–1001. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosand J, Eckman MH, Knudsen KA, Singer DE, Greenberg SM. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(8):880–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.8.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg SM, Eng JA, Ning M, Smith EE, Rosand J. Hemorrhage burden predicts recurrent intracerebral hemorrhage after lobar hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1415–20. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126807.69758.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donnell HC, Rosand J, Knudsen KA, Furie KL, Segal AZ, Chiu RI, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and the risk of recurrent lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(4):240–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001273420403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, Viswanathan A, Al-Shahi Salman R, Warach S, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(2):165–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A, Ikram MA, Wielopolski PA, Niessen WJ, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of cerebral microbleeds: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2008;70(14):1208–14. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000307750.41970.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poels MM, Ikram MA, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, Krestin GP, Breteler MM, et al. Incidence of cerebral microbleeds in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke. 2011;42(3):656–61. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poels MM, Ikram MA, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, Krestin GP, et al. Cerebral microbleeds are associated with worse cognitive function: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2012;78(5):326–33. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182452928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregoire SM, Scheffler G, Jager HR, Yousry TA, Brown MM, Kallis C, et al. Strictly lobar microbleeds are associated with executive impairment in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2013;44(5):1267–72. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soo YO, Yang SR, Lam WW, Wong A, Fan YH, Leung HH, et al. Risk vs benefit of anti-thrombotic therapy in ischaemic stroke patients with cerebral microbleeds. J Neurol. 2008;255(11):1679–86. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0967-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shoamanesh A, Kwok CS, Benavente O. Cerebral Microbleeds: Histopathological Correlation of Neuroimaging. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32(6):528–34. doi: 10.1159/000331466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loehrer E, Ikram MA, Akoudad S, Vrooman HA, van der Lugt A, Niessen WJ, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype influences spatial distribution of cerebral microbleeds. Neurobiol Aging. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Rooden S, van der Grond J, van den Boom R, Haan J, Linn J, Greenberg SM, et al. Descriptive analysis of the Boston criteria applied to a Dutch-type cerebral amyloid angiopathy population. Stroke. 2009;40(9):3022–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Wielopolski PA, Krestin GP, Breteler MM, van der Lugt A. Cerebral microbleeds: accelerated 3D T2*-weighted GRE MR imaging versus conventional 2D T2*-weighted GRE MR imaging for detection. Radiology. 2008;248(1):272–7. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nandigam RN, Viswanathan A, Delgado P, Skehan ME, Smith EE, Rosand J, et al. MR imaging detection of cerebral microbleeds: effect of susceptibility-weighted imaging, section thickness, and field strength. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(2):338–43. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordonnier C, Potter GM, Jackson CA, Doubal F, Keir S, Sudlow CL, et al. improving interrater agreement about brain microbleeds: development of the Brain Observer MicroBleed Scale (BOMBS) Stroke. 2009;40(1):94–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregoire SM, Chaudhary UJ, Brown MM, Yousry TA, Kallis C, Jager HR, et al. The Microbleed Anatomical Rating Scale (MARS): reliability of a tool to map brain microbleeds. Neurology. 2009;73(21):1759–66. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c34a7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng AL, Batool S, McCreary CR, Lauzon ML, Frayne R, Goyal M, et al. Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging is More Reliable Than T2*-Weighted Gradient-Recalled Echo MRI for Detecting Microbleeds. Stroke. 2013;44(10):2782–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linn J, Halpin A, Demaerel P, Ruhland J, Giese AD, Dichgans M, et al. Prevalence of superficial siderosis in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2010;74(17):1346–50. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dad605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charidimou A, Jager RH, Fox Z, Peeters A, Vandermeeren Y, Laloux P, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of cortical superficial siderosis in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2013;81(7):626–32. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a08f2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Reuck J, Deramecourt V, Cordonnier C, Auger F, Durieux N, Pasquier F, et al. Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system: a post-mortem 7.0-tesla magnetic resonance imaging study with neuropathological correlates. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36(5-6):412–7. doi: 10.1159/000355042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linn J, Wollenweber FA, Lummel N, Bochmann K, Pfefferkorn T, Gschwendtner A, et al. Superficial siderosis is a warning sign for future intracranial hemorrhage. J Neurol. 2013;260(1):176–81. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charidimou A, Peeters AP, Jager R, Fox Z, Vandermeeren Y, Laloux P, et al. Cortical superficial siderosis and intracerebral hemorrhage risk in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2013;81(19):1666–73. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435298.80023.7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurol ME, Viswanathan A, Gidicsin C, Hedden T, Martinez-Ramirez S, Dumas A, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy burden associated with leukoaraiosis: A positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging study. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(4):529–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.23830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prins ND, van Straaten EC, van Dijk EJ, Simoni M, van Schijndel RA, Vrooman HA, et al. Measuring progression of cerebral white matter lesions on MRI: visual rating and volumetrics. Neurology. 2004;62(9):1533–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123264.40498.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt R, Ropele S, Enzinger C, Petrovic K, Smith S, Schmidt H, et al. White matter lesion progression, brain atrophy, and cognitive decline: The Austrian stroke prevention study. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(4):610–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.20630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YW, Gurol ME, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Rakich SM, Groover TR, et al. Progression of white matter lesions and hemorrhages in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2006;67(1):83–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223613.57229.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verhaaren BF, Vernooij MW, de Boer R, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, van der Lugt A, et al. High blood pressure and cerebral white matter lesion progression in the general population. Hypertension. 2013;61(6):1354–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt R, Enzinger C, Ropele S, Schmidt H, Fazekas F. Progression of cerebral white matter lesions: 6-year results of the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study. Lancet. 2003;361(9374):2046–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13616-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith EE, Gurol ME, Eng JA, Engel CR, Nguyen TN, Rosand J, et al. White matter lesions, cognition, and recurrent hemorrhage in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2004;63(9):1606–12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000142966.22886.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Groot JC, de Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Jolles J, Breteler MM. Cerebral white matter lesions and depressive symptoms in elderly adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1071–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prins ND, van Dijk EJ, den Heijer T, Vermeer SE, Jolles J, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Cerebral small-vessel disease and decline in information processing speed, executive function and memory. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2005;128(Pt 9):2034–41. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Debette S, Beiser A, DeCarli C, Au R, Himali JJ, Kelly-Hayes M, et al. Association of MRI markers of vascular brain injury with incident stroke, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and mortality: the Framingham Offspring Study. Stroke. 2010;41(4):600–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inzitari D, Pracucci G, Poggesi A, Carlucci G, Barkhof F, Chabriat H, et al. Changes in white matter as determinant of global functional decline in older independent outpatients: three year follow-up of LADIS (leukoaraiosis and disability) study cohort. Bmj. 2009;339:b2477. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Longstreth WT, Jr, Arnold AM, Beauchamp NJ, Jr, Manolio TA, Lefkowitz D, Jungreis C, et al. Incidence, manifestations, and predictors of worsening white matter on serial cranial magnetic resonance imaging in the elderly: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Stroke. 2005;36(1):56–61. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000149625.99732.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dufouil C, Chalmers J, Coskun O, Besancon V, Bousser MG, Guillon P, et al. Effects of blood pressure lowering on cerebral white matter hyperintensities in patients with stroke: the PROGRESS (Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study) Magnetic Resonance Imaging Substudy. Circulation. 2005;112(11):1644–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.501163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mok VC, Lam WW, Fan YH, Wong A, Ng PW, Tsoi TH, et al. Effects of statins on the progression of cerebral white matter lesion: Post hoc analysis of the ROCAS (Regression of Cerebral Artery Stenosis) study. J Neurol. 2009;256(5):750–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Launer LJ, Miller ME, Williamson JD, Lazar RM, Gerstein HC, Murray AM, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering on brain structure and function in people with type 2 diabetes (ACCORD MIND): a randomised open-label substudy. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(11):969–77. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavalieri M, Schmidt R, Chen C, Mok V, de Freitas GR, Song S, et al. B vitamins and magnetic resonance imaging-detected ischemic brain lesions in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or stroke: the VITAmins TO Prevent Stroke (VITATOPS) MRI-substudy. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3266–70. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.665703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weber R, Weimar C, Blatchford J, Hermansson K, Wanke I, Moller-Hartmann C, et al. Telmisartan on top of antihypertensive treatment does not prevent progression of cerebral white matter lesions in the prevention regimen for effectively avoiding second strokes (PRoFESS) MRI substudy. Stroke. 2012;43(9):2336–42. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.648576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gouw AA, van der Flier WM, van Straaten EC, Pantoni L, Bastos-Leite AJ, Inzitari D, et al. Reliability and sensitivity of visual scales versus volumetry for evaluating white matter hyperintensity progression. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25(3):247–53. doi: 10.1159/000113863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith EE, Schneider JA, Wardlaw JM, Greenberg SM. Cerebral microinfarcts: the invisible lesions. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(3):272–82. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okazaki H, Reagan TJ, Campbell RJ. Clinicopathologic studies of primary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Mayo Clinic proceedings Mayo Clinic. 1979;54(1):22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soontornniyomkij V, Choi C, Pomakian J, Vinters HV. High-definition characterization of cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Hum Pathol. 41(11):1601–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Launer LJ, Hughes TM, White LR. Microinfarcts, brain atrophy, and cognitive function: the Honolulu Asia Aging Study Autopsy Study. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(5):774–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.22520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimberly WT, Gilson A, Rost NS, Rosand J, Viswanathan A, Smith EE, et al. Silent ischemic infarcts are associated with hemorrhage burden in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2009;72(14):1230–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345666.83318.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gregoire SM, Charidimou A, Gadapa N, Dolan E, Antoun N, Peeters A, et al. Acute ischaemic brain lesions in intracerebral haemorrhage: multicentre cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2011;134(Pt 8):2376–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menon RS, Burgess RE, Wing JJ, Gibbons MC, Shara NM, Fernandez S, et al. Predictors of highly prevalent brain ischemia in intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(2):199–205. doi: 10.1002/ana.22668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Auriel E, Gurol ME, Ayres A, Dumas AP, Schwab KM, Vashkevich A, et al. Characteristic distributions of intracerebral hemorrhage-associated diffusion-weighted lesions. Neurology. 2012;79(24):2335–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278b66f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Veluw SJ, Zwanenburg JJ, Engelen-Lee J, Spliet WG, Hendrikse J, Luijten PR, et al. In vivo detection of cerebral cortical microinfarcts with high-resolution 7T MRI. J Cerebr Blood F Met. 2013;33(3):322–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Westover MB, Bianchi MT, Yang C, Schneider JA, Greenberg SM. Estimating cerebral microinfarct burden from autopsy samples. Neurology. 2013;80(15):1365–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828c2f52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salat DH, Smith EE, Tuch DS, Benner T, Pappu V, Schwab KM, et al. White matter alterations in cerebral amyloid angiopathy measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Stroke. 2006;37(7):1759–64. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000227328.86353.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Viswanathan A, Patel P, Rahman R, Nandigam RN, Kinnecom C, Bracoud L, et al. Tissue microstructural changes are independently associated with cognitive impairment in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2008;39(7):1988–92. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.509091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nitkunan A, Barrick TR, Charlton RA, Clark CA, Markus HS. Multimodal MRI in cerebral small vessel disease: its relationship with cognition and sensitivity to change over time. Stroke. 2008;39(7):1999–2005. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.507475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teipel SJ, Wegrzyn M, Meindl T, Frisoni G, Bokde AL, Fellgiebel A, et al. Anatomical MRI and DTI in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: a European multicenter study. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2012;31(Suppl 3):S33–47. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Homayoon N, Ropele S, Hofer E, Schwingenschuh P, Seiler S, Schmidt R. Microstructural tissue damage in normal appearing brain tissue accumulates with Framingham Stroke Risk Profile Score: Magnetization transfer imaging results of the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Doubal FN, MacLullich AM, Ferguson KJ, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Enlarged perivascular spaces on MRI are a feature of cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke. 2010;41(3):450–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.564914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu YC, Tzourio C, Soumare A, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C, Chabriat H. Severity of dilated Virchow-Robin spaces is associated with age, blood pressure, and MRI markers of small vessel disease: a population-based study. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2483–90. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.591586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Charidimou A, Meegahage R, Fox Z, Peeters A, Vandermeeren Y, Laloux P, et al. Enlarged perivascular spaces as a marker of underlying arteriopathy in intracerebral haemorrhage: a multicentre MRI cohort study. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2013;84(6):624–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-304434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinez-Ramirez S, Pontes-Neto OM, Dumas AP, Auriel E, Halpin A, Quimby M, et al. Topography of dilated perivascular spaces in subjects from a memory clinic cohort. Neurology. 2013;80(17):1551–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828f1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Esiri MM, Wilcock GK, Morris JH. Neuropathological assessment of the lesions of significance in vascular dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(6):749–53. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang Z, Wang L, Xie H. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy with dementia: clinicopathological studies of 17 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 1999;112(3):238–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Natte R, Maat-Schieman ML, Haan J, Bornebroek M, Roos RA, van Duinen SG. Dementia in hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type is associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy but is independent of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Ann Neurol. 2001;50(6):765–72. doi: 10.1002/ana.10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haglund M, Sjobeck M, Englund E. Severe Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy Characterizes an Underestimated Variant of Vascular Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(2):132–7. doi: 10.1159/000079192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS) Lancet. 2001;357(9251):169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pfeifer LA, White LR, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Launer LJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive function: the HAAS autopsy study. Neurology. 2002;58(11):1629–34. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Wang Z, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Schneider JA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy pathology and cognitive domains in older persons. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2):320–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.22112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maat-Schieman ML, van Duinen SG, Bornebroek M, Haan J, Roos RA. Hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type (HCHWA-D): II--A review of histopathological aspects. Brain pathology. 1996;6(2):115–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Johnson KA, Gregas M, Becker JA, Kinnecom C, Salat DH, Moran EK, et al. Imaging of amyloid burden and distribution in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(3):229–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ly JV, Donnan GA, Villemagne VL, Zavala JA, Ma H, O'Keefe G, et al. 11C-PIB binding is increased in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related hemorrhage. Neurology. 2010;74(6):487–93. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cef7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Greenberg SM, Grabowski T, Gurol ME, Skehan ME, Nandigam RN, Becker JA, et al. Detection of isolated cerebrovascular beta-amyloid with Pittsburgh compound B. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(5):587–91. doi: 10.1002/ana.21528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dierksen GA, Skehan ME, Khan MA, Jeng J, Nandigam RN, Becker JA, et al. Spatial relation between microbleeds and amyloid deposits in amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):545–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.22099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gurol ME, Dierksen G, Betensky R, Gidicsin C, Halpin A, Becker A, et al. Predicting sites of new hemorrhage with amyloid imaging in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2012;79(4):320–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826043a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rinne JO, Brooks DJ, Rossor MN, Fox NC, Bullock R, Klunk WE, et al. (11)C-PiB PET assessment of change in fibrillar amyloid-beta load in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with bapineuzumab: a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):363–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Prada CM, Garcia-Alloza M, Betensky RA, Zhang-Nunes SX, Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, et al. Antibody-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta peptide from cerebral amyloid angiopathy revealed by quantitative in vivo imaging. J Neurosci. 2007;27(8):1973–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5426-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Salloway S, Sperling R, Gilman S, Fox NC, Blennow K, Raskind M, et al. A phase 2 multiple ascending dose trial of bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73(24):2061–70. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c67808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Clark CM, Schneider JA, Bedell BJ, Beach TG, Bilker WB, Mintun MA, et al. Use of florbetapir-PET for imaging beta-amyloid pathology. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305(3):275–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Jack CR, Jr, Jagust WJ, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw L, et al. The Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative: progress report and future plans. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6(3):202–11. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dumas A, Dierksen GA, Gurol ME, Halpin A, Martinez-Ramirez S, Schwab K, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging detection of vascular reactivity in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(1):76–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.23566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peca S, McCreary CR, Donaldson E, Kumarpillai G, Shobha N, Sanchez K, et al. Neurovascular decoupling is associated with severity of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 2013;81(19):1659–65. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435291.49598.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park L, Anrather J, Forster C, Kazama K, Carlson GA, Iadecola C. Abeta-induced vascular oxidative stress and attenuation of functional hyperemia in mouse somatosensory cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(3):334–42. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000105800.49957.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Han BH, Zhou ML, Abousaleh F, Brendza RP, Dietrich HH, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, et al. Cerebrovascular dysfunction in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice: contribution of soluble and insoluble amyloid-beta peptide, partial restoration via gamma-secretase inhibition. J Neurosci. 2008;28(50):13542–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4686-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Verbeek MM, Kremer BP, Rikkert MO, Van Domburg PH, Skehan ME, Greenberg SM. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta(40) is decreased in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(2):245–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.21694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Renard D, Castelnovo G, Wacongne A, Le Floch A, Thouvenot E, Mas J, et al. Interest of CSF biomarker analysis in possible cerebral amyloid angiopathy cases defined by the modified Boston criteria. J Neurol. 2012;259:2429–2433. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Senjem ML, Pankratz VS, Aisen PS, et al. Transforming cerebrospinal fluid Abeta42 measures into calculated Pittsburgh Compound B units of brain Abeta amyloid. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(2):133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.08.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hernandez-Guillamon M, Delgado P, Penalba A, Rodriguez-Luna D, Molina CA, Rovira A, et al. Plasma beta-Amyloid Levels in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy-Associated Hemorrhagic Stroke. Neurodegenerative diseases. 2012;10:320–3. doi: 10.1159/000333811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Greenberg SM, Cho HS, O'Donnell HC, Rosand J, Segal AZ, Younkin LH, et al. Plasma beta-amyloid peptide, transforming growth factor-beta 1, and risk for cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;903:144–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hernandez-Guillamon M, Martinez-Saez E, Delgado P, Domingues-Montanari S, Boada C, Penalba A, et al. MMP-2/MMP-9 plasma level and brain expression in cerebral amyloid angiopathy-associated hemorrhagic stroke. Brain pathology. 2012;22(2):133–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672–713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shimoyama T, Iguchi Y, Kimura K, Mitsumura H, Sengoku R, Kono Y, et al. Stroke patients with cerebral microbleeds on MRI scans have arteriolosclerosis as well as systemic atherosclerosis. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2012;35(10):975–9. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schmidt R, Fazekas F, Kapeller P, Schmidt H, Hartung HP. MRI white matter hyperintensities: three-year follow-up of the Austrian Stroke Prevention Study. Neurology. 1999;53(1):132–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Birns J, Jarosz J, Markus HS, Kalra L. Cerebrovascular reactivity and dynamic autoregulation in ischaemic subcortical white matter disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2009;80(10):1093–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.174607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]