Abstract

Significance: Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms are essential for epidermal homeostasis and contribute to the pathogenesis of many skin diseases, including skin cancer and psoriasis. However, while the epigenetic regulation of epidermal homeostasis is now becoming active area of research, the epigenetic mechanisms controlling the wound healing response remain relatively untouched.

Recent Advances: Substantial progress achieved within the last two decades in understanding epigenetic mechanisms controlling gene expression allowed defining several levels, including covalent DNA and histone modifications, ATP-dependent and higher-order chromatin chromatin remodeling, as well as noncoding RNA- and microRNA-dependent regulation. Research pertained over the last few years suggests that epigenetic regulatory mechanisms play a pivotal role in the regulation of skin regeneration and control an execution of reparative gene expression programs in both skin epithelium and mesenchyme.

Critical Issues: Epigenetic regulators appear to be inherently involved in the processes of skin repair, and are able to dynamically regulate keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, and migration, together with influencing dermal regeneration and neoangiogenesis. This is achieved through a series of complex regulatory mechanisms that are able to both stimulate and repress gene activation to transiently alter cellular phenotype and behavior, and interact with growth factor activity.

Future Directions: Understanding the molecular basis of epigenetic regulation is a priority as it represents potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of both acute and chronic skin conditions. Future research is, therefore, imperative to help distinguish epigenetic modulating drugs that can be used to improve wound healing.

Vladimir A. Botchkarev, MD, PhD

Scope and Significance

This review outlines our current knowledge of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms and their role in wound healing. In addition, the future directions of research and perspectives of using of epigenetic drugs for wound healing will be discussed.

Translational Relevance

The role of epigenetic mechanisms in regulation of wound healing stems from the earlier work that shows marked reorganization of the genome during tissue regeneration and cell reprogramming. Advances in understanding of epigenetic mechanisms controlling organ development and cell differentiation achieved during last decade provided a foundation for translation of these data toward the defining the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the control of wound healing.

Clinical Relevance

A significant portion of research in the area of epigenetic regulation resulted in the development of numerous epigenetic drugs that target distinct components of the epigenetic regulatory machinery. Application of epigenetic drugs for management of wound regenerative process will help in designing new therapeutic strategies and improving the current treatment protocols for wound healing.

Introduction

Epigenetics is defined as the discipline that studies the heritable changes in gene expression, resulting in alterations of the phenotype without modifications of the underlying DNA sequence.1 Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms are essential for epidermal homeostasis and contribute to the pathogenesis of many skin diseases, including skin cancer and psoriasis.2–4

In the epidermis, progenitor cells residing in the stratum basale proliferate and differentiate forming a multilayered structure, each stratum of which is functionally and structurally distinct.5,6 Epidermal stratification is integral to the properties of the skin, with the expression of keratins and cornified cell envelope proteins providing durability and water resistance, respectively.7 This process of cell cycle arrest and terminal differentiation is accompanied by changes in keratinocyte phenotype and gene expression, which are achieved through integration of signaling/transcription factor–mediated and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms.2,8

The nucleus plays a fundamental role in regulating gene expression and is a site of the storage, duplication, transcription, and repair of DNA.9–11 Within the nucleus, DNA is highly compacted into chromosomes, which occupy individual three-dimensional (3D) regions (territories) within the nuclear space.12 The nucleus co-ordinates gene expression using epigenetic regulatory mechanisms based on distinct chromatin structural states and their remodeling, including DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation, post-translational histone modifications, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling and higher-order chromatin structure, and 3D genome organization.13 The epigenetic mechanisms play a crucial role in the establishment and maintenance of cellular phenotypes in normal organs and tissues, as well as during pathological conditions, including tissue repair after injury.14

Biological response of the skin to injury includes reparation of the epidermal barrier to prevent ingress of microorganisms or extravasation of fluid.15,16 Cutaneous wound repair is achieved through a dynamic and highly complex process of cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation.15 Epigenetic signaling plays a key role in coordinating the behavior and activity of the multitude of cell types seen during skin repair, and research is now focusing on how epigenetic reprogramming enables upregulation of repair genes.17 These processes bear much similarity to those seen during embryonic morphogenesis,18 and epigenetic modifications are known to be crucial regulators of gene transcription during embryonic development.19 However, while the epigenetic regulation of epidermal homeostasis is now becoming active area of research, the epigenetic mechanisms controlling the wound healing response remain relatively untouched.

Here, we aim to highlight recent advances in understanding epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, with particular reference to those involved in normal keratinocyte homeostasis and skin repair. Because the roles of noncoding/microRNAs in the control of wound healing were reviewed quite extensively during last few years, we leave this topic out of the scope of the current review and address readers to the corresponding reviews and some original publications.20–22 We also propose future directions for exploration of epigenetic mechanisms, and their potential clinical applications in the treatment of acute and chronic wounds.

Chromatin organization and epigenetic regulation of keratinocyte gene expression

Chromatin is organized on several distinct structural levels, ultimately resulting in the formation of chromosomes, the largest units of genome organization.23 Nucleosomes are the most fundamental building block of chromatin, with each nucleosome core particle consisting of a complex of eight histone proteins (two of each histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) around which 147 base pairs of double-stranded DNA is wound.24 The nucleosomes and attached DNA appear as “beads-on-a-string” structure, and condense to form a fiber of ∼30-nm diameter, a process that requires a fifth histone known as H1, which pulls the nucleosomes together into a repeating pattern.25 This fiber undergoes further organization to form higher-order chromatin folding within 3D nuclear space. Here, we briefly review the mechanisms controlling chromatin organization and epigenetic regulation of gene expression in developing and postnatal homeostatic skin.

DNA methylation and hydroxymethylation

DNA methylation refers to a postreplication addition of a methyl group to the C5 position of cytosine to form 5-methylthytocyne. Occurring predominantly at cytosine-phosphate-guanine dinucleotides, this process is typically associated with gene repression and is performed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs).26 There are four principal DNMTs in mammals; DNMT1 is the major maintenance, while DNMT3A and DNMT3B are the de novo DNMTs, and DNMT3I, which lacks the catalytic domain, acts as an accessory DNMT by binding to DNMT3A/3B and facilitates their chromatin targeting.27

Within skin, DNMT1 is mainly involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and the maintenance of epidermal progenitor self-renewal capability.28,29 DNA methylation achieves this by predominantly suppressing gene expression by inhibiting transcription factor binding to DNA or by interacting with methyl-DNA-binding proteins that target repressive chromatin remodeling complexes to the methylated genomic regions.26 There are, however, instances where DNA methylation contributes to gene activation.30

Oxidation of 5-methylcytosine within DNA by the Tet family of proteins results in its conversion into 5-hydroxymethylcytosine.31 This represents a newly discovered epigenetic mechanism, and is thought to play key roles in regulating developmental gene expression and stem cell lineage commitment.32,33

Covalent histone modifications

Covalent histone modifications refer to the post-translational modifications of amino-acid side chains in these proteins. Histone methylation and acetylation are best-studied histone modifications. Histone methylation is catalyzed by methyltransferases and demethylases, and dynamically regulates gene activation or repression according to the extent of methylation and position of this modification in the histone proteins.34 For example, active gene expression is characterized by trimethylation of histone 3 at the lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and di- and trimethylation at lysine 79 (H3K79me2/3) positions, while gene repression is associated with trimethylation at H3K9, H3K27, and H4K20.35

Within the skin, histone methylation plays vital roles in epidermal stratification, proliferation, and differentiation.36 The histone demethylase JMJD3 regulates H3K27me3 demethylation, permitting activation of numerous differentiation-associated genes,36 while Setd8, a histone methyltransferase, which is responsible for histone H4K20 mono-methylation,37 is required for both epidermal proliferation and differentiation.

Histone acetylation and deacetylation are performed by histone acetyl transferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs), respectively.38 Histone acetylation can weaken the histone–DNA interactions, allowing transcription machinery access, and/or can target acetyl-lysine binding proteins to the specific genomic regions. It is typically associated with gene activation, while deacetylation is associated with gene repression.39,40 Enzymes controlling histone acetylation play key roles in the maintenance of stem cell populations both in the skin and other organs. Stem cells housed in the hair follicle bulge have deacetylated histone H4, correlating with their quiescent state; in contrast, the stem cell activation is associated with histone H4 acetylation.41 In mouse epidermis, HDAC1/2 contribute to the repression of some p63 target genes, such as p21 and p16INK4A, which are upregulated in the absence of the HDAC1/2 activity.42 Inhibition of HDACs by Trichostatin A (TSA) has been shown to inhibit in vitro keratinocyte and ex vivo skin proliferation and promote terminal differentiation through suppression of cell cycle regulators and upregulation of differentiation genes.43,44 These properties have highlighted the potential importance of HDAC inhibitors as potential anticancer therapies for a variety of diseases, including skin cancer.38

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are incorporated into at least two polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs), known as PRC1 and PRC2, both play roles in chromatin compaction and transcriptional silencing.45 But despite similar functions, they are structurally and biochemically distinct; PRC1 subunits include Bmi1, MEL18, Ring1A/1B, ring finger protein 2 (RNF2), Cbx, and Phi and PRC2 consists of Ezh2 or Ezh1, Suz12, and Eed.45,46

Both PRCs can work in tandem to regulate gene repression and maintain stem cell quiescence in many organs, including the skin. PRC2 is recruited to chromatin by still poorly understood mechanisms, where Ezh2 trimethylates lysine 27 on histone H3, and this trimethylation serves as a signal to recruit PRC1 and permits Polycomb-mediated gene suppression.45,46 PRCs can also suppress gene expression independently of each other.

Within the skin, PcG proteins appear to protect the quiescent state of stem cells,47 as well as playing roles in regulating epidermal differentiation and stratification.48 In developing skin, Ezh2 is expressed in basal keratinocytes while Ezh1 is seen in the suprabasal epidermis.49 Deletion of Ezh2 leads to premature epidermal differentiation due to a loss of PRC2-mediated gene repression, while simultaneous ablation of both Ezh1 and Ezh2 compromises hair follicle formation and leads to epidermal hyperproliferation.48,49

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes are able to modify DNA–histone interactions using energy of ATP hydrolysis.50 There are several distinct groups of the ATP-dependent remodeling complexes, including SWI/SNF, ISWI, and CHD groups, each containing an ATPase.50 The SWI/SNF group of proteins binds directly to acetylated histone tails, while the CHD group binds to DNA, RNA, and methylated histone H3.51

These ATPase-containing complexes are essential for skin development and the maintenance of homeostasis. Deletion of SWI/SNF complex component Brg1 results in a failure of keratinocyte terminal differentiation.52 Ablation of the CHD family member chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 4 (Chd4) during early skin development results in impaired stratum basale development; ablation during late morphogenesis impairs hair follicle development.53 In developing epidermis, Brg1 serves as direct target for p63 transcription factor and regulates relocation of the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) locus toward nuclear interior associated with marked increase of gene expression within the locus.54

Higher-order chromatin remodeling and 3D genome organization

Higher-order chromatin structure refers to the chromatin folding beyond “beads on the string” repeat. The position of chromosomes and subchromosomal regions is nonrandom within the interphase nucleus.12 It has been suggested that chromosomal positioning may be controlled by binding of specialized chromatin regions to the nuclear lamina network within the nucleus, or through interactions with nucleoli.55 This results in the formation of distinct domains, with interchromatin channels separating individual chromosomal structures in the nucleus.56

In normal epidermis, transition of keratinocytes from basal epidermal layer to the granular layer is accompanied by marked differences in nuclear architecture and is accompanied by internalization and decrease in the number of nucleoli, as well as by increase in the number of pericentromeric heterochromatic clusters and frequency of associations between pericentromeric clusters, chromosomal territory 3, and nucleoli.57 This suggests a role for nucleoli and pericentromeric heterochromatin clusters as organizers of nuclear microenvironment required for proper execution of gene expression programs in differentiating keratinocytes.57

Gene activation or silencing is frequently associated with a change in higher-order chromatin folding.13 In keratinocytes, AT-rich binding protein Satb1 regulates conformation of the central domain of the EDC locus containing genes activated during terminal keratinocyte differentiation.58 Ablation of Satb1 results in alterations of higher-order chromatin folding at and elongation of this domain, accompanied by marked alterations of gene expression and epidermal morphology.58 This suggests that proper chromatin folding at multigene tissue-specific loci is indeed important for maintenance of the proper balance of gene transcription in keratinocytes and outcomes of the transcription programs.

Epigenetic regulation of the wound healing response

Wound healing is a complex process that can be divided into four distinct phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.59 These stages are, however, not simple linear events, but rather overlapping in time and involve the transient activation and repression of up to 1,000 genes to achieve skin closure.60 Research pertained over the last few years suggests that epigenetic regulatory mechanisms play a pivotal role in the regulation of bone, spinal cord, and skin regeneration. Here we outline recent advances in understanding the role of epigenetic mechanisms in skin repair.

Dynamic expression patterns of epigenetic regulators during skin repair

Studies have illustrated that epigenetic modulators show contrasting spatial and temporal expression patterns in intact and healing skin. Shaw and Martin postulated that PcG proteins may play important roles in wound repair, and found that the expression of PRC2 complex components Ezh2, Suz12, and Eed was transiently downregulated during wound healing in in vivo murine models.61 Additionally, immunohistochemical expression patterns illustrated a paucity of Eed and Ezh2 at the wound margin, while it was abundant further away from the wound.61 In contrast, the expression of H3K27 histone demethylases JMJD3 and Utx was upregulated. Levels of both Eed and Ezh2 were, however, restored once re-epithelialization was complete, suggesting that there is a transient activation of repair genes via loss of PcG-protein-mediated silencing to permit epithelial closure.61 Our unpublished observations demonstrate that histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 are expressed in a human migrating wound epithelial tongue during skin regeneration, indicating their significant involvement during this process.

Epigenetic regulators modulate keratinocyte proliferation, migration, and differentiation during skin healing

Proliferation forms a vital facet of wound repair, as keratinocytes adjacent to the wound margin divide to provide a sufficient number for the processes of migration and epiboly. A number of epigenetic mechanisms have been shown to be involved in regulating proliferation, both in homeostatic epidermis and during wound repair. In intact skin, inactivation of DNMT1, the histone methyltransferase Setd8, HDAC1/2, Polycomb components Ezh1/2, and genome organizer Special AT-rich sequence binding protein 1 (SATB1) results in epidermal hypoplasia and suppression of proliferation-associated genes.29,36,42,48,58 In contrast, overexpression of Cbx4 and Chd4 impairs epidermal proliferation.47,53 But what effect do epigenetic regulators have on proliferation and differentiation during skin repair?

It is well established that hair follicles provide an accessible source of stem cells, which are vital for expeditious skin regeneration following injury.62 Ezhkova et al. investigated the effect of epigenetic modulation on stem cell activity in wound repair, finding that deletion of Ezh1 and Ezh2 slowed epidermal closure due to defective proliferation.49 Stem cell activity has also been shown to be modulated following the administration of DNMT and HDAC inhibitors, including 5-aza2′-deoxycitidine (5-aza-dC) and TSA, respectively.63 Wang et al. administered intraperitoneal injections of 5-aza-dC or TSA to mice that had undergone digital amputation. Mice treated with these drugs demonstrated increased proliferation, collagen deposition, and stem cell numbers at the amputation site, resulting in enhanced digital regeneration compared with controls.63

Antagonism of HDACs has also been shown to be beneficial in the regeneration of other tissues; in mice with spinal cord injuries treated with HDAC inhibitor valproic acid, apoptosis was reduced and functional recovery improved following treatment.64 In contrast, Taylor and Beck assessed the effect of valproic acid on amphibian tail regeneration, finding that in this model, HDAC inhibition retarded the regenerative process.65 Whether this variance is due to differences in tissue-specific responsiveness to HDAC manipulation remains to be elucidated; however, this does highlight the dramatic effect that epigenetic modulation may have on tissue repair and proliferation.

Epigenetic mechanisms are also vital for keratinocyte differentiation and stratification of the epidermis, both during homeostasis and following injury. Studies have illustrated that deletion of DNMT1 leads to premature keratinocyte differentiation, while deletion of Setd8, JMJD3, and HDAC1/2 results in impaired epidermal stratification.29,42,48 JMJD3 overexpression leads to accelerated differentiation (Sen et al.) while Cbx4 deletion enhances keratinocyte differentiation.36,47 Their role in re-stratification following injury, however, remains to be elucidated.

To achieve epidermal closure following wounding, keratinocytes adjacent to the wound margin must migrate as a sheet in a process known as epiboly. Migrating keratinocytes produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), including MMP-9 and -1; these specifically degrade type-IV collagen and laminins in the basement membrane, allowing cells to leave and migrate to the wound. Epigenetic modulation is able to regulate this migration in a variety of ways, though studies that examine the direct effect of epigenetics on keratinocyte migration are limited. Uchida et al. examined the effect of HDAC inhibitors TSA and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) on in vitro endometrial adenocarcinoma migration, finding it to be accelerated.66 Epigenetic mechanisms may also have a profound effect on MMP production, which could influence keratinocyte migration.67 HDAC and DNMT inhibition has been shown to differentially enhance or repress MMP production,67,68 potentially leading to acceleration or slowing of cell migration. Indeed, 5-azacytidine, a potent inhibitor of DNMTs, retards MMP-2 production and invasion of pancreatic carcinoma.69

Epigenetic reprogramming and the dermis: key roles in collagen synthesis, neoangiogenesis, and remodeling

The dermis undergoes major regeneration and restructuring following skin injury and is re-established in a process known as fibroplasia; this involves fibroblast proliferation and formation of type III collagen and other matrix proteins.59 Subpopulations of fibroblasts transform into myofibroblasts to aid wound contraction and produce new immature collagen fibrils, which will later be remodeled to become mature type IV collagen. Epigenetics has been shown to alter the behavior of fibroblasts during wound healing and collagen production. Glenisson et al. established that HDAC4 is required for transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGFβ-1)–mediated myofibroblastic differentiation70; correspondingly, HDAC inhibitors negate this transformation.71 Additionally, HDACs also appear necessary for myofibroblastic collagen production, as HDAC inhibition with TSA blocks collagen gene expression in human fibroblasts.72,73 Russell et al. studied the epigenetic status of keloid fibroblasts, finding that their phenotype and propensity to form benign dermal tumors may be due to differential methylation of proliferative genes.74 HDAC inhibition with TSA has been shown to inhibit collagen synthesis and promote apoptosis of keloid fibroblasts,75 suggesting that modulation of their epigenetic status may aid in the treatment of this condition.

Neoangiogenesis, stimulated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and TGF-β, permits angiogenic capillary buds to grow into the wound bed and form a microvascular network. Both vascular growth factors and their receptors are subjected to epigenetic regulation. VEGF signaling, which is critical for vascular morphogenesis and endothelial differentiation, is attenuated by HDAC inhibition.76 Additionally, human umbilical vein endothelial cells fail to form capillary buds following treatment with TSA and SAHA.76 The PcG family of proteins are also involved in the processes of angiogenesis; VEGF-mediated stimulation of angiogenic activity is accompanied by upregulation of Ezh2.77,78 Endothelial expression of Ezh2 by VEGF has also been illustrated in tumor vasculature,78 supporting a link between epigenetic mechanisms and growth factor signaling.

Summary

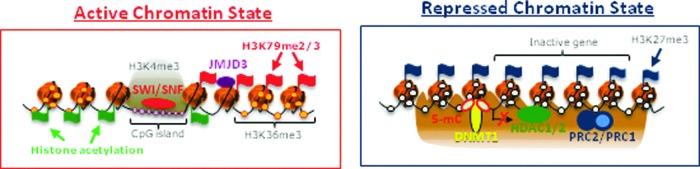

Epigenetic regulators appear to be inherently involved in the processes of skin repair, and are able to dynamically regulate keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, and migration, together with influencing dermal regeneration and neoangiogenesis. This is achieved through a series of complex regulatory mechanisms that are able to both stimulate and repress gene activation to transiently alter cellular phenotype and behavior, and interact with growth factor activity (Fig. 1). Understanding the molecular basis of this regulation is a priority as it represents potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of both acute and chronic skin conditions. Future research is, therefore, imperative to help distinguish epigenetic modulating drugs that can be used to treat skin disorders.

Figure 1.

Scheme illustrating transcriptionally active and repressed chromatin states in keratinocytes. Active gene transcription is maintained by coordinated involvement of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers Brg1 and Mi-2b and histone demethylase JMJD3 that support formation of “open” chromatin structure. Inhibition of transcription is associated with presence of DNA methyltransferase 1, HDAC1/2, and components of the Polycomb complexes Cbx4, Ezh1/2, and Bmi1, which promote formation of the repressive chromatin structure. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES.

• Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms operate at several levels, including covalent DNA and histone modifications, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling, as well as higher-order chromatin remodeling, and nuclear compartmentalization of the genes and transcription machinery.

• Distinct epigenetic regulators show dynamic patters of expression during skin repair.

• Epigenetic regulators modulate keratinocyte proliferation, migration, and differentiation during wound healing.

• Epigenetic machinery plays key roles in collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling.

• Epigenetic drugs need to be tested for management of the wound-induced regenerative process and research in this direction will help in improving the current treatment protocols used for wound healing.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DNMTs

DNA methyltransferases

- EDC

epidermal differentiation complex

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- PcG

polycomb group

- PRCs

polycomb repressive complexes

- SAHA

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- TGFβ-1

transforming growth factor beta-1

- TSA

Trichostatin A

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Berger SL, Kouzarides T, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev 2009;23:781–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botchkarev VA, Gdula MR, Mardaryev AN, Sharov AA, Fessing MY. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 2012;132:2505–2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millington GW. Epigenetics and dermatological disease. Pharmacogenomics 2008;9:1835–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Chen ZQ, Cui PG, et al. The methylation pattern of p16INK4a gene promoter in psoriatic epidermis and its clinical significance. Br J Dermatol 2008;158:987–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009;10:207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchs E. Scratching the surface of skin development. Nature 2007;445:834–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segre JA. Epidermal barrier formation and recovery in skin disorders. J Clin Invest 2006;116:1150–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Back SJ, Im M, Sohn KC, et al. Epigenetic Modulation of Gene Expression during Keratinocyte Differentiation. Ann Dermatol 2012;24:261–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert N, Gilchrist S, Bickmore WA. Chromatin organization in the mammalian nucleus. Int Rev Cytol 2005;242:283–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rippe K. Dynamic organization of the cell nucleus. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2007;17:373–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowat AC, Lammerding J, Herrmann H, Aebi U. Towards an integrated understanding of the structure and mechanisms of the cell nucleus. BioEssays 2008;30:226–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cremer T, Cremer M. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010;2:a003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bickmore WA, van Steensel B. Genome architecture: domain organization of interphase chromosomes. Cell 2013;152:1270–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinberg AP. Genome-scale approaches to the epigenetics of common human disease. Virchows Arch 2010;456:13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beyer TA, Auf dem Keller U, Braun S, Schafer M, Werner S. Roles and mechanisms of action of the Nrf2 transcription factor in skin morphogenesis, wound repair and skin cancer. Cell Death Differ 2007;14:1250–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2008;16:585–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw TJ, Martin P. Wound repair at a glance. J Cell Sci 2009;122:3209–3213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin P, Parkhurst SM. Parallels between tissue repair and embryo morphogenesis. Development 2004;131:3021–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemberger M, Dean W, Reik W. Epigenetic dynamics of stem cells and cell lineage commitment: digging Waddington's canal. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009;10:526–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pastar I, Ramirez H, Stojadinovic O, et al. Micro-RNAs: new regulators of wound healing. Surg Technol Int 2011;XXI:51–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pastar I, Khan AA, Stojadinovic O, et al. Induction of specific microRNAs inhibits cutaneous wound healing. J Biol Chem 2012;287:29324–29335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee J, Sen CK. MicroRNAs in skin and wound healing. Methods Mol Biol 2013;936:343–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cremer T, Cremer C. Chromosome territories, nuclear architecture and gene regulation in mammalian cells. Nat Rev Genet 2001;2:292–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luger K, Dechassa ML, Tremethick DJ. New insights into nucleosome and chromatin structure: an ordered state or a disordered affair? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012;13:436–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felsenfeld G, Groudine M. Controlling the double helix. Nature 2003;421:448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng S, Jacobsen SE, Reik W. Epigenetic reprogramming in plant and animal development. Science 2010;330:622–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goll MG, Bestor TH. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem 2005;74:481–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khavari DA, Sen GL, Rinn JL. DNA methylation and epigenetic control of cellular differentiation. Cell Cycle 2010;9:3880–3883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sen GL, Reuter JA, Webster DE, Zhu L, Khavari PA. DNMT1 maintains progenitor function in self-renewing somatic tissue. Nature 2010;463:563–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rishi V, Bhattacharya P, Chatterjee R, et al. CpG methylation of half-CRE sequences creates C/EBPalpha binding sites that activate some tissue-specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:20311–20316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams K, Christensen J, Helin K. DNA methylation: TET proteins-guardians of CpG islands? EMBO Rep 2011;13:28–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y, Wu F, Tan L, et al. Genome-wide regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell 2011;42:451–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu TP, Guo F, Yang H, et al. The role of Tet3 DNA dioxygenase in epigenetic reprogramming by oocytes. Nature 2011;477:606–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 2007;129:823–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA., et al. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet 2008;40:897–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sen GL, Webster DE, Barragan DI, Chang HY, Khavari PA. Control of differentiation in a self-renewing mammalian tissue by the histone demethylase JMJD3. Genes Dev 2008;22:1865–1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Driskell I, Oda H, Blanco S, et al. The histone methyltransferase Setd8 acts in concert with c-Myc and is required to maintain skin. EMBO J 2012;31:616–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kretsovali A, Hadjimichael C, Charmpilas N. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cell pluripotency, differentiation, and reprogramming. Stem Cells Int 2012;2012:184154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, et al. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell 2007;131:633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Araki Y, Wang Z, Zang C, et al. Genome-wide analysis of histone methylation reveals chromatin state-based regulation of gene transcription and function of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 2009;30:912–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frye M, Fisher AG, Watt FM. Epidermal stem cells are defined by global histone modifications that are altered by Myc-induced differentiation. PLoS One 2007;2:e763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LeBoeuf M, Terrell A, Trivedi S, et al. Hdac1 and Hdac2 act redundantly to control p63 and p53 functions in epidermal progenitor cells. Dev Cell 2010;19:807–818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elder JT, Zhao X. Evidence for local control of gene expression in the epidermal differentiation complex. Exp Dermatol 02002;11:406–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markova NG, Karaman-Jurukovska N, Pinkas-Sarafova A, Marekov LN, Simon M. Inhibition of histone deacetylation promotes abnormal epidermal differentiation and specifically suppresses the expression of the late differentiation marker profilaggrin. J Invest Dermatol 2007;127:1126–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Bardot E, Ezhkova E. Epigenetic regulation of skin: focus on the Polycomb complex. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012;69:2161–2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rajasekhar VK, Begemann M. Concise review: roles of polycomb group proteins in development and disease: a stem cell perspective. Stem Cells 2007;25:2498–2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luis NM, Morey L, Mejetta S, et al. Regulation of human epidermal stem cell proliferation and senescence requires polycomb- dependent and -independent functions of Cbx4. Cell Stem Cell 2011;9:233–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ezhkova E, Pasolli HA, Parker JS, et al. Ezh2 orchestrates gene expression for the stepwise differentiation of tissue-specific stem cells. Cell 2009;136:1122–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ezhkova E, Lien WH, Stokes N, et al. EZH1 and EZH2 cogovern histone H3K27 trimethylation and are essential for hair follicle homeostasis and wound repair. Genes Dev 2011;25:485–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu Rev Biochem 2009;78:273–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hargreaves DC, Crabtree GR. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics and mechanisms. Cell Res 2011;21:396–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Indra AK, Dupe V, Bornert JM, et al. Temporally controlled targeted somatic mutagenesis in embryonic surface ectoderm and fetal epidermal keratinocytes unveils two distinct developmental functions of BRG1 in limb morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Development 2005;132:4533–4544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kashiwagi M, Morgan BA, Georgopoulos K. The chromatin remodeler Mi-2beta is required for establishment of the basal epidermis and normal differentiation of its progeny. Development 2007;134:1571–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mardaryev AN, Gdula MR, Yarker JL, et al. p63 and Brg1 control developmentally regulated higher-order chromatin remodelling at the epidermal differentiation complex locus in epidermal progenitor cells. Development 2014;141:101–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joffe B, Leonhardt H, Solovei I. Differentiation and large scale spatial organization of the genome. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2010;20:562–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Markaki Y, Gunkel M, Schermelleh L, et al. Functional nuclear organization of transcription and DNA replication: a topographical marriage between chromatin domains and the interchromatin compartment. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2010;75:475–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gdula MR, Poterlowicz K, Mardaryev AN, et al. Remodelling of three-dimensional organization of the nucleus during terminal keratinocyte differentiation in the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:2191–2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fessing MY, Mardaryev AN, Gdula MR, et al. p63 regulates Satb1 to control tissue-specific chromatin remodeling during development of the epidermis. J Cell Biol 2011;194:825–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, Longaker MT. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008;453:314–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooper L, Johnson C, Burslem F, Martin P. Wound healing and inflammation genes revealed by array analysis of ‘macrophageless’ PU.1 null mice. Genome Biol 2005;6:R5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaw T, Martin P. Epigenetic reprogramming during wound healing: loss of polycomb-mediated silencing may enable upregulation of repair genes. EMBO Rep 2009;10:881–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, et al. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nat Med 2005;111351–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang G, Badylak SF, Heber-Katz E, Braunhut SJ, Gudas LJ. The effects of DNA methyltransferase inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors on digit regeneration in mice. Regen Med 2010;5:201–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lv L, Sun Y, Han X, et al. Valproic acid improves outcome after rodent spinal cord injury: potential roles of histone deacetylase inhibition. Brain Res 2011;1396:60–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taylor AJ, Beck CW. Histone deacetylases are required for amphibian tail and limb regeneration but not development. Mech Dev 2012;129:208–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uchida H, Maruyama T, Ono M, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors stimulate cell migration in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells through up-regulation of glycodelin. Endocrinology 2007;148:896–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clark IM, Swingler TE, Sampieri CL, Edwards DR. The regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2008;40:1362–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pender SL, Quinn JJ, Sanderson IR, MacDonald TT. Butyrate upregulates stromelysin-1 production by intestinal mesenchymal cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2000;279:G918–G924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chernov AV, Strongin AY. Epigenetic regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and their collagen substrates in cancer. Biomol Concepts 2011;2:135–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Glenisson W, Castronovo V, Waltregny D. Histone deacetylase 4 is required for TGFbeta1-induced myofibroblastic differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007;1773:1572–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guo W, Shan B, Klingsberg RC, Qin X, Lasky JA. Abrogation of TGF-beta1-induced fibroblast-myofibroblast differentiation by histone deacetylase inhibition. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009;297:L864–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rombouts K, Niki T, Greenwel P, et al. Trichostatin A, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, suppresses collagen synthesis and prevents TGF-beta(1)-induced fibrogenesis in skin fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res 2002;278:184–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ghosh AK, Mori Y, Dowling E, Varga J. Trichostatin A blocks TGF-beta-induced collagen gene expression in skin fibroblasts: involvement of Sp1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;354:420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russell SB, Russell JD, Trupin KM, et al. Epigenetically altered wound healing in keloid fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 2010;130:2489–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diao JS, Xia WS, Yi CG, et al. Trichostatin A inhibits collagen synthesis and induces apoptosis in keloid fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res 2011;303:573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deroanne CF, Bonjean K, Servotte S, et al. Histone deacetylases inhibitors as anti-angiogenic agents altering vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Oncogene 2002;21:427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smits M, Mir SE, Nilsson RJ, et al. Down-regulation of miR-101 in endothelial cells promotes blood vessel formation through reduced repression of EZH2. PLoS One 2011;6:e16282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Turunen MP, Yla-Herttuala S. Epigenetic regulation of key vascular genes and growth factors. Cardiovasc Res 2011;90:441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]