Abstract

Visceral leishmaniasis is an anthropozoonosis that is caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania, especially Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum, and is transmitted to humans by the bite of sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, such as Lutzomyia longipalpis. There are many reservoirs, including Canis familiaris. It is a chronic infectious disease with systemic involvement that is characterized by three phases: the initial period, the state period and the final period. The main symptoms are fever, malnutrition, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia. This article reports a case of a patient diagnosed with visceral leishmaniasis in the final period following autochthonous transmission in the urban area of Rio de Janeiro. The case reported here is considered by the Municipal Civil Defense and Health Surveillance of Rio de Janeiro to be the first instance of autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis in humans in the urban area of this city. The patient was discharged and is undergoing a follow-up at the outpatient clinic, demonstrating clinical improvement.

Keywords: Visceral leishmaniasis, Transmission, Epidemiology

Abstract

A leishmaniose visceral é uma antropozoonose causada por protozoários do gênero Leishmania, principalmente Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum e transmitida ao homem pela picada do flebotomíneo do gênero Lutzomyia, destacando-se no Brasil a Lutzomyia longipalpis. Os animais reservatórios são muitos, tendo o cão doméstico (Canis familiaris) como principal reservatório. Trata-se de uma doença infecciosa crônica, de envolvimento sistêmico e caracterizado por três fases: período inicial, período de estado e período final. As principais manifestações são febre, hepatoesplenomegalia, desnutrição e pancitopenia. Este artigo tem como objetivo relatar o caso de paciente diagnosticada com leishmaniose visceral em período final, de transmissão autóctone na área urbana da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. O caso relatado neste artigo é considerado, após investigação, pela Secretaria Municipal de Saúde e Defesa Civil do Rio de Janeiro como o primeiro caso autóctone de leishmaniose visceral em humanos na área urbana da cidade do Rio de Janeiro. O tratamento oferecido foi eficaz e a paciente encontra-se em acompanhamento ambulatorial.

INTRODUCTION

Visceral leishmaniasis is an anthropozoonosis that is caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania, especially Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum, and is transmitted to humans by the bite of sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, such as Lutzomyia longipalpis. There are many reservoirs, including Canis familiaris in urban areas, foxes and marsupials in rural areas.

The first case of visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil was recorded in 1913 in Porto Esperança, Mato Grosso do Sul. Afterward, in the 1930s, a major investigation in the northeast part of the country confirmed 41 cases of visceral leishmaniasis during autopsies of suspected cases of yellow fever. The following years were characterized by new cases emerging in rural areas in more than ten states. After the 1940s, with Vargas government's investment in the urbanization of the country, cases were also recorded in areas of rural-urban transition. L. longipalpis seems to be well adapted to peridomiciles, but the many factors that influence this organism's sporadic presence in urban areas are still poorly understood. However, the transmission of visceral leishmaniasis in areas close to major urban centers in Brazil has been reported1,4. In 1979, the first autochthonous case in Rio de Janeiro was reported by SALAZAR and confirmed by SOUZA in 1981, with the demonstration of the presence of the L. longipalpis and enzootic cases of visceral leishmaniasis in dogs at this region11. Since then, there are about 87 cases of autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis confirmed in peri-urban areas in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro7.

Visceral leishmaniasis is a chronic infectious disease with systemic involvement that is characterized by three phases: the initial period, the state period and the final period. The incubation period can range from 10 days to 24 months, with only a small proportion of infected individuals manifesting the disease. The initial period includes fever, pallor and hepatosplenomegaly, which are occasionally accompanied by coughing and diarrhea. Certain cases may be oligosymptomatic. The state period is characterized by intermittent fever, weight loss and increased hepatosplenomegaly, as well as the deterioration of the individual's general condition. The final period of disease development occurs when the individual experiences severe malnutrition, pancytopenia, jaundice and ascites. Death is typically the result of opportunistic infections and bleeding2.

This article reports a case of a patient diagnosed with visceral leishmaniasis in the final period following autochthonous transmission in the urban area of Rio de Janeiro. The case reported here is considered by the Municipal Civil Defense and Health Surveillance of Rio de Janeiro to be the first instance of autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis in humans in the urban area of this city.

CASE REPORT

The patient was female, 29 years old and single; born and living in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro; resident of Cajú neighborhood, working as a cleaner in the cemetery of Cajú, RJ. She denied any trips outside of the city limits of Rio de Janeiro throughout her life. Five months before the hospitalization, the patient experienced an intermittent night fever of 39 °C that was not improved by antipyretics and was accompanied by poor appetite, postprandial fullness, nausea and vomiting episodes. There was no history of liver disease or alcohol abuse. Between the months from October to December 2012, she gradually noticed yellow sclera and skin, dark urine, and weight loss of approximately 10 kg, increased abdominal size and a soft and cold edema of the lower limbs up to the knees. The patient sought treatment in emergency units on several occasions but only received symptomatic prescriptions. In January 2013, she was admitted for diagnostic investigation to the 10th ward of the Gaffrée and Guinle University Hospital, UNIRIO.

A physical examination revealed poor general health, malnutrition, numbness, pallor +3/+4, dehydrated +1/+4, jaundice +2/+4, cyanosis, fever, tachycardia and eupnea. An abdominal examination revealed moderate ascites, hepatomegaly that was 7 cm from the right costal margin and splenomegaly that was palpable 2 cm below the navel (Fig. 1). Additionally, the lower limbs showed bilateral soft edema up to the knees.

Fig. 1. Abdominal examination revealing hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. 98 × 73 mm (150 × 150 DPI).

Laboratory examinations (Table 1) revealed a complete blood count showing severe pancytopenia, an extended prothrombin time, a significant elevation of the aminotransferase levels, hypoalbuminemia and hypergammaglobulinemia accompanied by severe jaundice with a cholestatic pattern. A total abdominal ultrasound evaluation revealed the presence of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity, hepatomegaly of approximately 20 cm, splenomegaly of 25 cm and gallstones.

Table 1. Laboratorial exams during internation.

| Parameter | References | 04/01/13 | 10/01/13 | 21/01/13 | 06/02/13 | 20/02/13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | (11.0-18.8) | 6.44 | 5.40 | 8.37 | 11.5 | 11.4 |

| Ht | (35.0-55.0) | 19.8% | 15.9% | 18.3% | 36.7% | 36.9% |

| MCV | (80.0-100) | 76.8 | 77.5 | 85.0 | 86.5 | 84.6 |

| MCH | (26.0-34.0) | 25.0 | 26.3 | 26.1 | 27.2 | 26.1 |

| MCHC | (31.0-35.0) | 32.5 | 34.0 | 30.6 | 31.4 | 30.8 |

| RDW | (11.0-15.0) | 20.3% | 19.8% | 18.3% | 16.6% | 15.7% |

| WBC | (4000-11000) | 435 | 548 | 3210 | 5250 | 4360 |

| Platelets | (150000-400000) | 30100 | 46400 | 98400 | 172000 | 106000 |

| HSV | (< 15) | 28 | - | - | 10 | - |

| INR | (1.00) | 3.07 | 1.379 | - | 1.584 | - |

| TTP(Rel) | (1.00) | Incoag | 1.80 | - | 1.05 | - |

| Creatinine | (0.7-1.3) | 1.02 | 2.58 | 1.03 | 1.23 | 1.45 |

| Urea | (10-50) | 48 | 75 | 36 | 45 | 55 |

| AST | (< 38) | 1557 | 137 | 111 | 42 | 18 |

| ALT | (< 41) | 329 | 154 | 82 | 37 | 24 |

| Alcalin Fosfatase | (65-300) | 136 | 545 | 1280 | 532 | 429 |

| GGT | (11-50) | 34 | 284 | 694 | 486 | 467 |

| Direct Bilirubin | (< 0.3) | 9.39 | 5.26 | 2.02 | 1.21 | 0.73 |

| Indirect Bilirubin | (< 0.8) | 5.23 | 2.04 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 0.39 |

| Albumin | (3.5-4.8) | 1.3 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| Globulin | (1.4-3.2) | 4.7 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.3 |

| K+ | (3.6-5.5) | 4.0 | 2.95 | 2.68 | 3.00 | 2.34 |

| Na+ | (134-149) | 138 | 148 | 146 | 153 | 145 |

| Cl– | (94-112) | 105 | 113 | 102 | 106 | 103 |

| Ca++ | (8.5-10.5) | 6.5 (8.7) | 6.7 (9.1) | 8.0 (8.4) | 8.9 | 9.5 (9.9) |

| Mg++ | (1.7-2.5) | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| P | (2.5-4.5) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 3.7 |

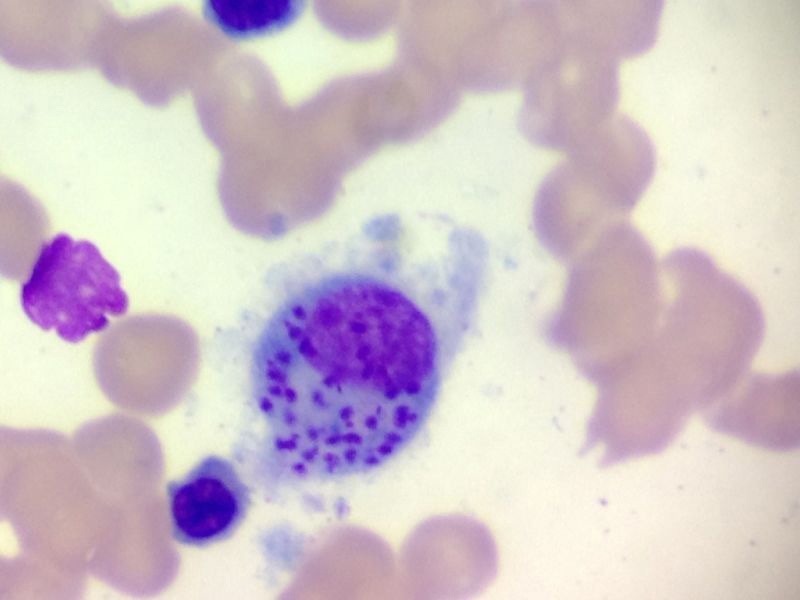

The diagnostic hypotheses contemplated disseminated tuberculosis and visceral leishmaniasis. Other hypotheses covered dengue, yellow fever, prolonged septicemic salmonellosis, brucellosis, malaria, Chagas disease and lymphoproliferative malignancies. An evaluation by thick and thin blood smear, blood culture, stool tests, bone marrow biopsy and aspiration and serology for dengue, yellow fever, brucellosis and Chagas disease were requested. A diagnosis of AIDS was refuted by HIV testing. The bone marrow aspirate confirmed the presence of Leishmania amastigotes (Fig. 2). The case was reported by telephone immediately, followed by an investigation by the Municipal Civil Defense and Health Surveillance. Infected dogs were found in the cemetery in Cajú and were sacrificed. The Municipal Civil Defense and Health Surveillance then implemented a plan to combat the vector, to improve environmental sanitation and to search for new cases, which initially yielded two new suspected cases.

Fig. 2. The bone marrow aspirate confirming the presence of Leishmania amastigotes. 282 × 211 mm (72 × 72 DPI).

For the patient, a therapeutic regimen was initiated with amphotericin B at 0.25 mg/kg/day diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose and 1000 IU heparin and infused for 6 h. We routinely administered a dose of 100 mg hydrocortisone IV and one g dipyrone IV prior to infusion to reduce the probability of an allergic reaction to amphotericin B. The dose of amphotericin B was increased by approximately 2.5 mg every 3-5 days if there were no complications, such as severe hypokalemia, cardiac arrhythmia or a significant increase in creatinine. Adjustments and suspension of the amphotericin B treatment were necessary for a few days because of increased creatinine levels and hypokalemia. Electrolyte replacements were also needed, as well as therapy to treat iron deficiency-related anemia and the extension of the prothrombin time, which included 300 mg ferrous sulfate orally twice daily, 5 mg folic acid PO daily and 10 mg vitamin K SC in a single dose.

Over a period of seven weeks (January-February 2013), a cumulative dose of 700 mg amphotericin B was administered. Fever reduction, an improvement in the level of consciousness, a noticeable improvement in general health and nutrition and a significant reduction of hepatosplenomegaly were noted during the treatment. Laboratory tests showed pancytopenia and the progressive improvement of dyscrasia, the normalization of liver enzyme levels and cholestasis (Table 1). The patient was discharged in February 2013 and is undergoing a follow up at the outpatient clinic, demonstrating clinical improvement.

DISCUSSION

The presence of the vector L. longipalpis in the state of Rio de Janeiro has been documented in the southern part of the country, on Marambaia Island, in the municipality of the cities of Mangaratiba and Saquarema3,9. Cases of the autochthonous transmission of canine visceral leishmaniasis were reported in the southern part of the city of Rio de Janeiro, in the Laranjeiras neighborhood, and in the city of Angra dos Reis5,10. Moreover, sporadic cases of tegumentary leishmaniasis have been reported in the country, especially in Pau da Fome in the Jacarepagua neighborhood6, and periurban cases of visceral leishmaniasis have been reported in the Maciço de Pedra Branca (Serra do Barata in Realengo and Rio da Prata in the district of Campo Grande)7,8,12 and the continental slope of the Maciço de Gericinó7. However, the case reported in this article is considered by the Municipal Civil Defense and Health Surveillance of Rio de Janeiro to be the first report of autochthonous visceral leishmaniasis in humans in the urban area of Rio de Janeiro. Measures for vector control, reservoir targeting and the improvement of environmental sanitation as well as a search for new cases are now underway to prevent further transmission.

According to information collected from the patient and the employees of the Cajú cemetery, dogs belonging to people buried in the cemetery are often abandoned beside the graves of their owners. Certain cases involved people from the south of the state or other regions with canine leishmaniasis who potentially owned infected dogs. A few cemetery employees took care of the abandoned dogs, providing food and water and thus maintaining the presence of the animals in the cemetery. L. longipalpis has been found in the area of the Cajú cemetery, so it is likely that this peculiar situation facilitated the urban transmission of visceral leishmaniasis in this region.

The absence of visceral leishmaniasis cases recorded in the urban area of Rio de Janeiro certainly influenced the delay to diagnose the patient, who was diagnosed in the final phase of the disease.

From a clinical perspective, this case was a typical manifestation of visceral leishmaniasis in the final period. We chose to use amphotericin B for treatment because antimonials are contraindicated in cases of liver failure, and the patient presented cholestatic jaundice, hypoalbuminemia and an increased INR2. Amphotericin B was used at a cumulative dose of 0.25 mg/kg/day diluted with 500 mL 5% dextrose and 1000 IU heparin and infused for six hours. The patient had an estimated dry weight of 45 kg. The administration of a dose of 100 mg hydrocortisone IV and one g dipyrone IV, prior to infusion, was routinely performed to reduce the probability of an allergic reaction to amphotericin B. The dose of amphotericin was increased by approximately 2.5 mg every 3-5 days if there were no complications, such as severe hypokalemia, cardiac arrhythmia or a significant increase in creatinine. The treatment proved to be effective at a cumulative dose of 700 mg, which required approximately seven weeks of treatment. The increased creatinine levels and hypokalemia were controlled during hospitalization. At the end of the therapy, the patient's splenomegaly was reduced by approximately 60%, the fever was gone, and the pancytopenia was completely reversed. This presentation dismissed any more tests for parasitologic control.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alencar JE. Expansão do Calazar no Brasil. Ceará Méd. 1983;5:86–102. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brasil.Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Manual de vigilância e controle da leishmaniose visceral. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde; 2006. pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brazil RP, Pontes MCQ, Passos WL, Fuzari AA, Brazil BG. Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the region of Saquarema: potential area of visceral leishmaniasis transmission in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:120–121. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822012000100023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcanti AT, Medeiros Z, Lopes F, Andrade LD, Ferreira VM, Magalhães V, Miranda-Filho DB. Diagnosing visceral leishmaniasis and HIV/AIDS co-infection: a case series study in Pernambuco, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2012;54:43–47. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652012000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueiredo FB, Barbosa CJ, Filho, Schubach EY, Pereira SA, Nascimento LD, Madeira MF. Relato de caso autóctone de leishmaniose visceral canina na zona sul do município do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:98–99. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822010000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawa H, Sabroza PC, Oliveira RM, Barcellos C. A produção do lugar de transmissão da leishmaniose tegumentar: o caso da Localidade Pau da Fome na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Publica. 2010;26:1495–507. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2010000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marzochi MC, Fagundes A, Andrade MV, Souza MB, Madeira MF, Mouta-Confort E, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: eco-epidemiological aspects and control. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2009;42:570–80. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822009000500017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marzochi MC, Sabroza PC, Toledo LM, Marzochi KB, Tramontano NC, Rangel-Filho F. Leishmaniose visceral na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 1985;1:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novo SPC. Levantamento da fauna de flebotomíneos, vetores de leishmanioses, na Ilha de Marambaia, município de Mangaratiba, Rio de Janeiro. [dissertação] Rio de Janeiro: Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Souza MB, Carvalho RW, Machado RNM, Wermelinger ED. Flebotomíneos de áreas com notificações de casos autóctones de leishmaniose visceral canina e leishmaniose tegumentar americana em Angra dos Reis, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Rev Bras Entomol. 2009;53:147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souza MA, Sabroza PC, Marzochi MC, Coutinho SG, Souza WJ. Leishmaniose visceral no Rio de Janeiro. Flebotomíneos da área de procedência de caso humano autóctone. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1981;76:161–168. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761981000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toledo LM. Leishmaniose tegumentar e visceral em área peri-urbana no município do Rio de Janeiro. [dissertação] Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 1987. [Google Scholar]