Abstract

Nondiphtherial corynebacteria are ubiquitous in nature and commonly colonize the skin and mucous membranes of humans, however they rarely account for clinical infection. We present the first reported case of multiple pulmonary nodules caused by Corynebacterium striatum. The infection occurred in a 72-year-old immunocompetent female, and the diagnosis was obtained by Gram's stain and culture of lung biopsy. C. striatum should be recognized as a potential pathogen in both immunocompromised and normal hosts in the appropriate circumstances.

Keywords: Multiple nodules, Corynebacterium striatum

Abstract

Bacilos não diftéricos são ubiquitários na natureza e comumente colonizam a pele e as membranas mucosas humanas, contudo eles raramente acarretam doença clínica. Apresentamos o primeiro relato de múltiplos nódulos causados por Corynebacterium striatum. A infecção ocorreu numa mulher imunocompetente de 72 anos de idade e o diagnóstico foi obtido pela coloração de Gram e cultivo de biópsia pulmonar. C. striatum deve ser reconhecido como potencial patógeno tanto em pacientes imunodeprimidos como em hospedeiros normais, em circunstâncias apropriadas.

INTRODUCTION

The Corynebacteria are a group of aerobic, gram-positive, non-sporulating, predominantly non-motile rods. Due to their saprophytic nature most diphtheroid isolates in man are ignored and attributed to contamination from skin or mucous membrane sources. In the last decade, an increasing number of studies have reported different species of Corynebacterium causing infections in underlying immunosuppressive conditions. However, we report the first of multiple pulmonary nodules caused by Corynebacterium striatum, in a 72-year-old immunocompetent female.

CASE REPORT

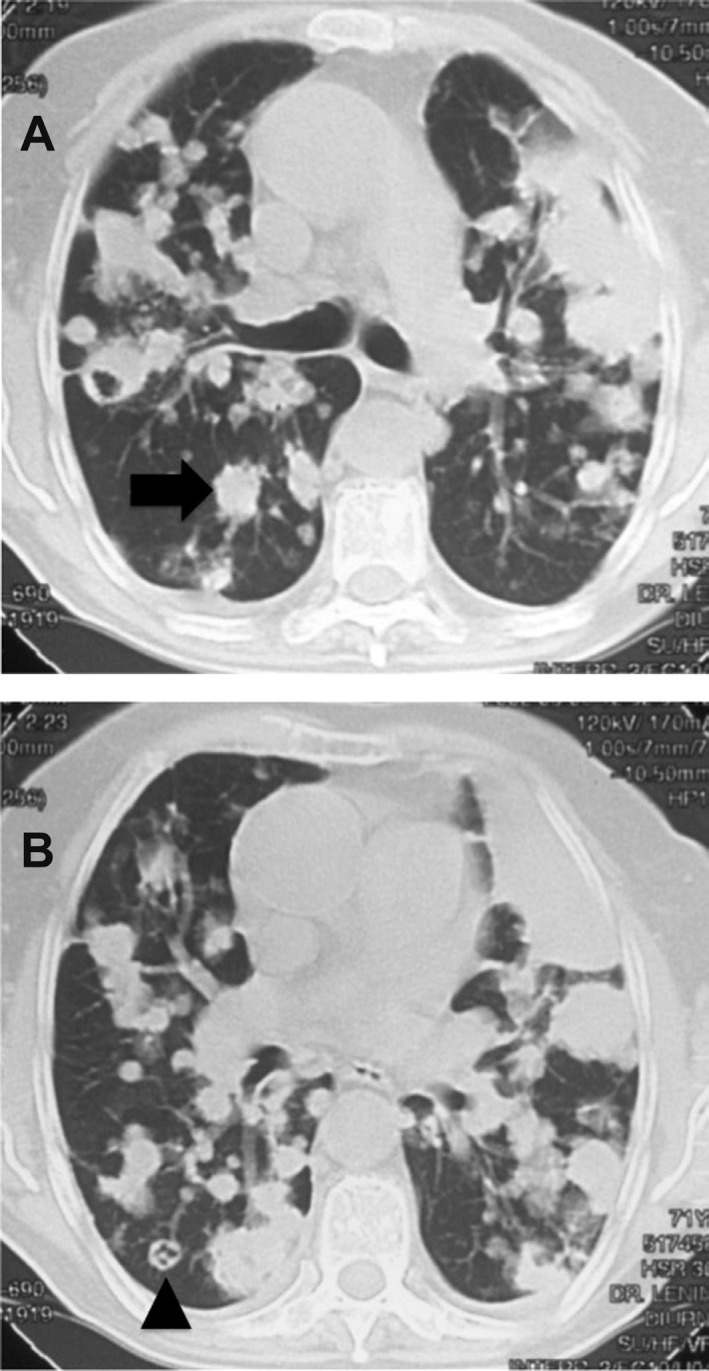

A 72-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with right-sided pleuritic chest pain, cough with purulent sputum, fatigue and shortness of breath. Her pulse was 90 beats per minute, blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, respiration was 22/min, and temperature was 37 °C. On physical examination, the patient appeared thin but healthy. There was no history of smoking tobacco. Her past medical history was remarkable only for coronary disease and hypertension, which were subsequently treated with appropriate drugs. An HIV test was negative and no other underlying disease was detected. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple pulmonary nodules in the lower lobes. The CT scan also demonstrated some cavitary lung lesions with a feeding vessel sign in the lower lobes (Fig 1).

Fig. 1. A computed tomography scan revealing multiple pulmonary nodules (arrow in A) in the lower lobes. The scan also demonstrates some cavitary lung lesions (arrowhead in B) with feeding vessel sign in the lower lobes. These imaging findings suggest secondary vascular implants that could be of infectious or neoplastic etiology.

Microscopic examinations of sputum were negative for acid-fast bacilli and fungi; cytologic examination showed no malignant tumor cells. Blood cultures were negative. Needle biopsy of the lung was performed under CT guidance and revealed lung parenchyma with elastofibrosis and anthracosis.

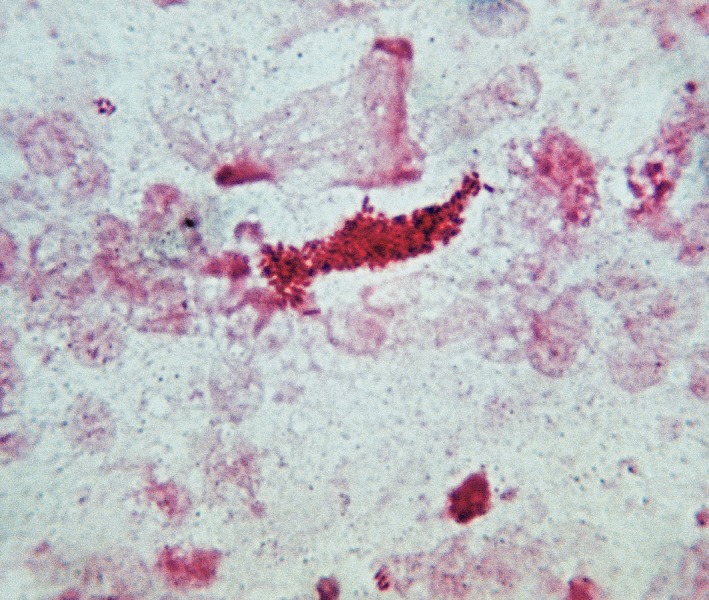

Examination of the lung fragment by direct microscopy showed multiple non-acid-fast (Ziehl-Neelsen), gram-positive rods (Fig 2). The searches for malignant (H&E) and fungus (Grocott) cells were negative. Culture on blood agar yielded pure growth of an organism identified as Corynebacterium striatum (99.7% probability) by the API-CORYNE system (BioMérieux Marcy l'Etoile, France). Laboratory investigations revealed hemoglobin concentrations of 9.3 g/d, a total white blood cell count of 12 × 109/L with 80% neutrophils, 7% bands, 9% lymphocytes, and 3% monocytes; platelets of 452 × 109/L, and a erythrocyte sedimentations rate of 55 mm/hour. Routine blood chemistry was normal. Creatinine was 1.6 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase was 82 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 42 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase 30 U/L. Antibiotic susceptibility was tested by the disk diffusion method (Oxoid SA, Spain) in Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% blood for all antibiotics tested including penicillin (10U), gentamicin (10 µg), vancomycin (30 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), and tetracycline (30 µg). The susceptibility criteria of the CLSI for Staphylococcus spp. were used for all antibiotics, which result in sensitivity for erythromycin and vancomycin, and resistance for all the others. The patient was treated with erythromycin (500 mg/qds) and rifampin (600 mg/daily), both administered orally. Despite therapy, relentless deterioration continued, resulting in death 12 days after respiratory failure.

Fig. 2. Imprint smear of lung tissue. Gram's stain showing clusters of gram-positive bacilli of Corynebacterium striatum.

DISCUSSION

The genus Corynebacterium forms a group of 81 validly described species, 50 of which can cause clinical disease in humans5. C. striatum is ubiquitous and colonizes the skin and mucous membranes of normal hosts and hospitalized patients8,14. C. striatum has been one of the more commonly isolated coryneform bacteria in the clinical microbiology laboratory10. Reports of true infection, confirmed by isolation of C. striatum from a sterile site, are rare and have been reported mainly in patients with indwelling devices or immunosuppression6. We herein present the first reported case of multiple pulmonary nodules due to C. striatum in a previously healthy patient, diagnosed by lung biopsy.

Reports of C. striatum are extremely rare. It is part of the normal microbiota of skin and cutaneous membranes and very often is considered contaminant. However, C. striatum was included in a variety of different types of infection: pneumonia and empyema, CSF-shunt infection, endocarditis, peritonitis, arthritis, keratitis, intra-uterine infections, wound infection, breast abscess, osteomyelitis11. Many cases of infection were hospital-acquired, namely wound infections. The discrimination between colonization and infection is difficult in some cases, especially nosocomial infection. Serious infections with C. striatum have been reported only sporadically1.

A pulmonary cavity is a gas-filled area of the lung in the center of a nodule or area of consolidation; it may be clinically observed by a plain chest radiography or CT. Cavities are present in a wide variety of infectious and noninfectious processes. A cavity can be the result of any of a number of pathological processes, including suppurative necrosis (e.g., pyogenic lung abscess), caseous necrosis (e.g., tuberculosis), ischemic necrosis (e.g., pulmonary infarction), cystic dilatation of lung structures (e.g., ball valve obstruction and Pneumocystis pneumonia), or displacement of lung tissue by cystic structures (e.g., Echinococcus). In addition, malignant processes may cavitate because of treatment-related necrosis, internal cyst formation, or internal desquamation of tumor cells with subsequent liquefaction4.

In CT, the feeding vessel sign consists of a distinct vessel leading directly into the center of the nodule. This sign has been considered highly suggestive of septic embolism, the prevalence varying from 67 to 100% in various series7. However, the feeding vessel sign also occurs in about 20% of pulmonary metastases13. These imaging findings suggest secondary vascular implants that could be of infectious or neoplastic etiology. This is the first reported case of multiple pulmonary nodules resulting from infection by C. striatum. The presence of multiple pulmonary nodules with a negative tissue diagnosis of malignancy was the key to a presumptive diagnosis of another fatal pulmonary infection2,9 with this emerging respiratory pathogen3.

The learning point of this fatal pulmonary infection by C. striatum with isolation of a pure culture, diagnosed by lung biopsy, in the absence of other recognized respiratory pathogens and knowing the high levels of antibiotic resistance, including to erythromycin and rifampicin, is that the empiric use of these drugs despite the susceptibility to the erythromycin, was not adequate.

Finally, the vancomicin could be candidate to the first-line therapeutic option for treatment of C. striatum 5, but reports of true infections confirmed by isolation from a sterile site, like our case, are rare12. Furthermore, the threat of emerging resistance of available anti-C. striatum drugs highlights the need for the continuing investigation of the biology of this organism as the usefulness of these drugs can only be assessed in randomized clinical trials.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brandenburg AH, van Belkum A, van Pelt CV, Bruining HA, Mouton JW, Verbrugh HA. Patient-to-patient spread of a single strain of Corynebacterium striatum causing infections in a surgical intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2089–2094. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2089-2094.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowstead TT, Santiago SM. Pleuropulmonary infection due to Corynebacterium striatum . Br J Dis Chest. 1980;74:198–200. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(80)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Díez-Aguilar M, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Fernández-Olmos A, Guisado P, Del Campo R, Quereda C, et al. Non-diphtheria Corynebacterium species: an emerging respiratory pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:769–772. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodd GD, Boyle JJ. Excavating pulmonary metastases. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1961;85:277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funke G, Graevenitz A, Clarridge JE 3rd, Bernard KA. Clinical microbiology of coryneform bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:125–159. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Funke G, Bernard KA. Corynebacterium gram-positive. In: Versalovic J, editor. Manual of clinical microbiology. Washington: ASM Press; 2011. pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhlman JE, Fishman EK, Teigen C. Pulmonary septic emboli: diagnosis with CT. Radiology. 1990;174:211–213. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.1.2294550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Martinez L, Suárez AI, Rodríguez-Baño J, Bernard K, Munián MA. Clinical significance of Corynebacterium striatum isolated from human samples. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:634–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Martinez L, Suárez AI, Ortega MC, Rodríguez-Jiménez R. Fatal pulmonary caused by Corynebacterium striatum . Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:806–807. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Martinez L, Suárez AI, Winstanley J, Ortega MC, Bernard K. Phenotypic characteristics of 31 strains of Corynebacterium striatum isolated from clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2458–2461. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2458-2461.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin MC, Mélon O, Celada MM, Alvarez J, Méndez FJ, Vásquez F. Septicaemia dueto to Corynebacterium striatum: molecular confirmation of entry via the skin. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:599–602. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer DK, Reboli AC. Other coryneform bacteria and rhodococci. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. 7th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. pp. 2695–2706. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murata K, Takahashi M, Mori M, Kawaguchi N, Furukawa A, Ohnaka Y, et al. Pulmonary metastatic nodules: CT-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1992;182:331–335. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.2.1732945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins DA, Chahine A, Creger RJ, Jacobs MR, Lazarus HM. Corynebacterium striatum: a diphtheroid with pathogenic potential. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:21–25. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]