Abstract

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is an autosomal recessive disease associated with high levels of branched-chain amino acids. Children with MSUD can present severe neurological damage, but liver transplantation (LT) allows the patient to resume a normal diet and avoid further neurological damage. The use of living related donors has been controversial because parents are obligatory heterozygotes. We report a case of a 2-year-old child with MSUD who underwent a living donor LT. The donor was the patient's mother, and his liver was then used as a domino graft. The postoperative course was uneventful in all three subjects. DNA analysis performed after the transplantation (sequencing of the coding regions of BCKDHA, BCKDHB, and DBT genes) showed that the MSUD patient was heterozygous for a pathogenic mutation in the BCKDHB gene. This mutation was not found in his mother, who is an obligatory carrier for MSUD according to the family history and, as expected, presented both normal clinical phenotype and levels of branched-chain amino acids. In conclusion, our data suggest that the use of a related donor in LT for MSUD was effective, and the liver of the MSUD patient was successfully used in domino transplantation. Routine donor genotyping may not be feasible, because the test is not widely available, and, most importantly, the disease is associated with both the presence of allelic and locus heterogeneity. Further studies with this population of patients are required to expand the use of related donors in MSUD.

Keywords: Heterozygous donor, Metabolic disease, Branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase mutation, Leucine, Genotype

Introduction

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder that results in decreased activity of the branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) complex, leading to accumulation of the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) leucine, isoleucine, and valine. MSUD presents locus heterogeneity, which means that it can be caused either by mutations in BCKDHA, BCKDHB, or DBT genes or by allelic heterogeneity (1). In developing countries, where there is no neonatal screening for MSUD in public healthcare, the diagnosis is usually based on a combination of clinical (irritability, poor feeding, lethargy, intermittent apnea) and biochemical findings in which high levels of leucine, isoleucine, or valine are detected in serum by quantitative methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography, but the other amino acids are in the normal or low ranges. Measurement of alloisoleucine, BCKDH activity, and DNA analysis are not widely available.

Leucine, isoleucine, and valine are toxic to the central nervous system and can produce different grades of neuropathy, or even death, if the disease is not treated (2). Because the liver is responsible for around 15% of enzymatic BCKDH production, liver transplantation (LT) can restore some enzymatic activity in MSUD patients (3). Indeed, a decrease in leucine concentration has been observed hours after performing LT in patients with MSUD, using deceased donors (3). Since livers from MSUD patients are structurally normal, they are a source of grafts for domino liver transplantation (DLT) (4). This case report describes a successful DLT in which the donor was the mother of the recipient with MSUD.

Patients and Methods

Patient 1

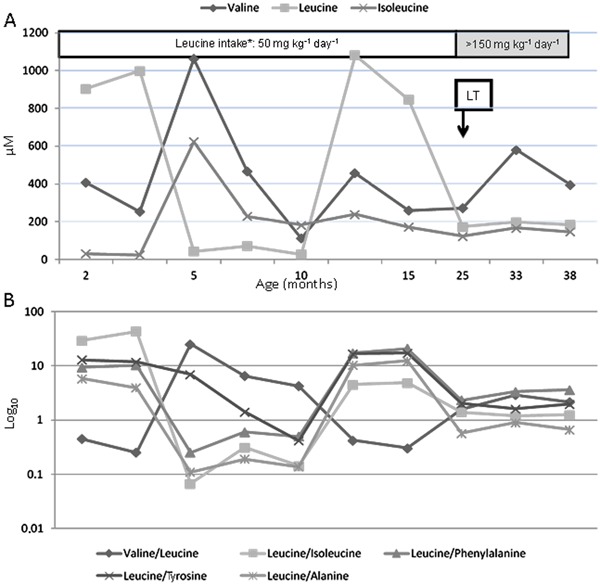

Patient 1, a 2-year-old boy, son of a nonconsanguineous couple, was diagnosed with the classic form of MSUD 5 days after birth following an uneventful prenatal period. He was discharged from the hospital at 48 h of life. He was exclusively breastfed after being discharged. On day 5 the patient presented lethargy and on day 7 he was in a coma, and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). His first sibling had been diagnosed with MSUD during the neonatal period and died 2 months after birth. In the ICU, the BCAA levels of Patient 1 were leucine, 904 µM [normal reference values (NRV): 47-155 µM]; isoleucine, 31 µM (NRV: 31-86 µM); and valine, 406 µM (NRV: 64-294 µM). A restricted diet (leucine tolerance 55 mg·kg-1·day-1) was started in the ICU. During his first year of life, the patient had three ICU admissions for respiratory infections associated with high levels of leucine, and because of difficulty swallowing, a gastrostomy tube was inserted to provide nutrition. At the age of 12 months and weighing 9800 g (z score height/age: -1.49), the patient was referred to our group for evaluation for LT. At this point, we had no information about his genotype. During evaluation for transplantation, he was found to present significant neurological and psychomotor disability, axial hypotonia, and seizures. His pretransplantation plasma leucine level was 846.2 µM (Figure 1), and his pediatric end-stage liver disease (PELD) score was -1.

Figure 1. A, Pre- and post-transplantation branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) levels of the recipient with maple syrup urine disease. B, Molar relationship between BCAAs (log10). LT: liver transplantation.

Patient 2

Patient 2 was a 33-month-old boy with biliary atresia who underwent a portoenterostomy. He had portal hypertension (esophageal varices) and also presented repeated episodes of cholangitis. Pretransplantation laboratory test results were hemoglobin, 9.7 mg/dL; total bilirubin (TB), 12.8 mg/dL; sodium, 138 mEq/L; urea, 22 mg/dL; and creatinine, 0.26 mg/dL. He weighed 13 kg, his z score height/age was -1.73, and PELD score was 11. He was selected to receive the DLT because of ABO blood type compatibility and size match.

Living donor

The donor for Patient 1 was his 41-year-old mother. She had neither a previous record of metabolic decompensation nor a history of comorbidities, except for a previous laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Because she had two siblings with MSUD, she was assumed to be a heterozygote (i.e., an obligatory carrier) with a normal phenotype. Indeed, her preoperative aminoacidogram was normal; with valine, 161.5 µM (NRV: 130-307 µM); leucine, 96.5 µM (NRV: 65-179 µM); and isoleucine, 38.3 µM (NRV: 33-97 µM). All the patients or their parents gave informed consent and the study was approved by the hospital's Ethics Committee.

Genotype

The decision to perform the DLT was based on phenotypic characteristics of both the donor and the MSUD recipient. Genotyping was not available at the time of the transplantation. Afterward, it was possible to include both the donor and Patient 1 in a national research study aimed at characterizing MSUD mutations (the Brazilian MSUD Network), with the approval of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre Ethics Committee. There was no sample from the father for genotyping.

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes of the mother and the patient, and all exon and exon-intron boundaries of BCKDHA, BCKDHB, and DBT were analyzed by direct sequencing to identify possible mutations.

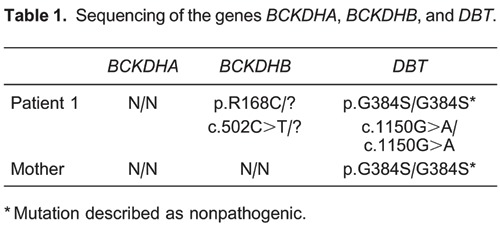

The mutation found in the MSUD patient and his mother is reported in Table 1.

Postoperative courses

The living donor had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged from the hospital 5 days after the procedure. She was on an unrestricted diet and experienced no adverse events during follow-up (13 months after the donation).

Patient 1 remained stable throughout and after the transplantation. On postoperative day (POD) 1, he was started on a diet of restricted leucine intake (70 mg·kg-1·day-1) via the gastrostomy tube. This intake was subsequently increased from 70 to 156 mg·kg-1·day-1. An aminoacidogram was performed on POD 2 and his plasma leucine level was 210 µM (NRV: <205 µM). He experienced an episode of acute cellular rejection on POD 7. He was discharged on POD 17 and readmitted 40 days later due to a cytomegalovirus infection. Patient 1 did not present any metabolic decompensation after the transplantation. Laboratory test results 13 months after the transplantation were: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 51 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 42 IU/L; gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), 82 IU/L, and TB, 0.2 mg/dL. Figure 1 shows the variations in BCAA levels pre- and post-transplantation.

Neurologically, this patient showed significant improvement; the hypotonia diminished, and he was able to stand with assistance. He did not experience seizures. However, he continued to have difficulty swallowing and still used a gastrostomy tube.

Patient 2 remained stable after the transplantation and was discharged from the hospital on POD 18. Laboratory test results 13 months post-transplantation were: AST, 41 IU/L; ALT, 24 IU/L; GGT, 11 IU/L; and TB, 0.35 mg/dL. An aminoacidogram performed 8 months post-transplantation indicated normal levels of leucine (122 µM), isoleucine (73 µM), and valine (225 µM).

Discussion

LT was discovered as a treatment for MSUD after transplantations had been performed for nonmetabolic reasons in the first patients (5). These patients achieved good metabolic control and their leucine levels normalized in the immediate postoperative period. After that, the Pittsburgh Group reported the results for 10 additional patients transplanted for MSUD with whole livers. They achieved 100% patient and graft survival after a median follow-up of 14 months. All patients were on normal diets (3). In 2012, Mazariegos et al. (6) expanded their group's experience and reported on 37 patients transplanted for MSUD along with 17 patients from the United Network for Organ Sharing database. Only one patient underwent living donor LT. Based on this experience, the authors argue that LT provides adequate metabolic control with normal diet and better neurological development and eliminates the risk of sudden brain edema and death (3,6,7). The efficacy of LT for MSUD indicates that introducing about 10% of normal BCKDH activity on a whole body basis is sufficient to maintain peripheral amino acid homeostasis. The transplanted liver in the MSUD recipient becomes responsible for over 90% degradation of BCAAs, resulting in normal plasma leucine levels (8). LT not only eliminates high and variable BCAA levels, but also protects children from essential amino acid deficiencies, which may be equally important in the optimization of physical and neurological development.

Livers from MSUD patients can be used for DLT. Domino livers were first considered as marginal grafts because the disease could manifest in the domino recipient (9). However, recipients of liver grafts from MSUD donors will probably not develop protein intolerance because 60% of BCKDH activity occurs in the muscle. This is enough to permit normal protein intake and prevent metabolic decompensation under stress (6). Mazariegos et al. (6), in their follow-up study on transplanted patients for MSUD, mention that six of these patients consented to donating grafts. The recipients of these grafts had 100% survival and normal BCAA homeostasis thereafter.

To our knowledge, there have been no reports of the use of a related donor for MSUD. The only reported case was an unsuccessful living donor LT, and the recipient died because of vascular complications. However, the authors did not specify whether the case involved a heterozygous donor (6). There are some concerns about using a related donor. First, based on the inheritance mode of the disease, parents are most probably obligate heterozygotes and express 50% of BCKDH activity. Second, theoretically, providing less liver mass with less BCKDH activity might not prevent metabolic crises under stress (6). Our study shows that neither the donor nor the recipient experienced metabolic decompensation after the transplantation. The recipient's leucine levels were within normal ranges on the second POD, without dietary restrictions. Forty days after the transplantation, during the treatment for a cytomegalovirus infection, Patient 1 did not go into metabolic crisis.

In the evaluation of related living donors for metabolic diseases, the determination of the donor's heterozygote status is based on the mode of inheritance of each disease. Depending on the specific deficiency, biochemical assays are carried out for each donor before deciding to proceed with the transplantation. Morioka et al. (10) only performed genetic evaluation if biochemical assays were abnormal for the specific metabolic disease. However, there were no MSUD cases in their series.

MSUD is a heterogeneous disease with various phenotypes, including silent types. Silent phenotypes harbor the mutation and express enough BCKDH activity to prevent the full clinical phenotype (1,11). Although inheritance of MSUD adheres to a simple autosomal recessive pattern, mutations in each of the three BCKDH-specific genes can cause the disease (1). Patients with intermediate and intermittent types may vary from 2 to 40% of BCKDH activity (11). Heterozygotes express 50% of BCKDH activity (12). Usually, this is enough to prevent any phenotypical expression (13).

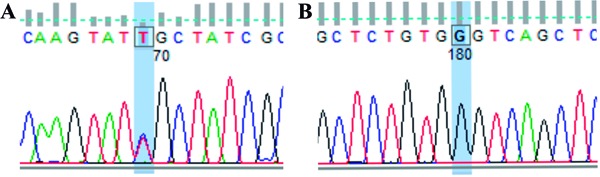

The mother and the recipient with MSUD were referred to our center after the diagnosis was established, and we had no information about the mutations. Based on previous family genetic studies, it was highly probable that the mother would be an obligate heterozygote (1,12,14). So far, there had been only one reported case of a mother and child with the intermittent forms of MSUD (15). However, the genotyping was inconclusive and we were able to demonstrate the presence of only one pathogenic mutation in the proband and none in the mother. The mutations presented in Patient 1 are represented in Figure 2 and Table 1. The heterozygous mutation [c.502C>T (p.R168C)] was already described by Flaschker et al. (11) and has been associated with MSUD in the Human Gene Mutation Database. The homozygous mutation [c.1150G>A (p.G384S)] was also found by Tsuruta et al. (16), but its role in the development of the disease is still under debate. This mutation could be responsible for creating instability in the protein structure of the enzymatic complex. However, according to Henneke et al. (17), this missense mutation (G384S), previously described as pathogenic (16), can actually represent a polymorphism, because both MSUD patients studied who carried this homozygous mutation had other pathogenic mutations in different subunits of the BCKDH gene. Also, according to MutPred version 1.2 (18), c.502C>T is probably damaging to protein function and c.1150G>A is probably not protein damaging. Most likely, the second pathogenic mutation present in the proband of Patient 1, which was inherited from his mother, is located in some of the noncoding regions of the BCKDHB gene or is an exonic and whole gene-deletion mutation, both of which are usually not detectable through the strategy used in the present study. Additional studies will confirm this possibility.

Figure 2. DNA sequencing of Patient 1. A, Analysis of exon 5 of the BCKDHB gene: base C (blue) was exchanged by T (red) - R168C. B, Analysis of exon 9 of the DBT gene: base A (green) was exchanged by G (black) - G384S.

After the introduction of the Modified-PELD allocation system in Brazil in August 2006 (19), children listed for transplantation received priority when competing for adult livers. However, the utilization of split LT is restricted to the use of ideal donors, because good results should be expected for both recipients. Two problems exist. First, the MSUD recipients receive a lower score when competing with pediatric patients with end-stage liver disease. Second, the livers from ideal donors are mainly used in adult patients with fulminant liver failure, retransplants, high model for end-stage liver disease candidates, and sick pediatric patients with chronic liver disease. In this scenario, patients with MSUD are at a disadvantage when competing for livers from the list, and the use of live donors is justified for patients with metabolic noncirrhotic liver diseases. The safety in using heterozygous living donors for metabolic diseases was evaluated (10,20), and there was no difference in survival or incidence of complications when comparing heterozygous with nonheterozygous donors. No heterozygous donor developed any kind of metabolic decompensation following the donation. None of the recipients had recurrence of the original disease after a median follow-up of 7 years (10).

In conclusion, our data suggest that the use of a related donor in LT for MSUD was effective, and the liver of the MSUD patient was successfully used in domino transplantation. The decision in this case to use a related donor was based both on the clinical phenotype and the demonstration of normal BCAA levels in the donor. Routine donor genotyping may not be feasible because the test is not widely available, and, most importantly, because the disease is associated with both the presence of allelic and locus heterogeneity. Further studies with this population of patients are required to expand the use of related donors in MSUD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nucleus of Research Support (NAP), the Center for Integrative Systems Biology (CISBi), and University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil, for their support. Research supported by the Brazilian Maple Syrup Urine Disorder Network (grant MCT/CNPq/CT-SAUDE #57/2010).

Footnotes

First published online May 2, 2014.

References

- 1.Nellis MM, Danner DJ. Gene preference in maple syrup urine disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:232–237. doi: 10.1086/316950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauss KA, Morton DH. Branched-chain ketoacyl dehydrogenase deficiency: maple syrup disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5:329–341. doi: 10.1007/s11940-003-0039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss KA, Mazariegos GV, Sindhi R, Squires R, Finegold DN, Vockley G, et al. Elective liver transplantation for the treatment of classical maple syrup urine disease. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popescu I, Dima SO. Domino liver transplantation: how far can we push the paradigm? Liver Transpl. 2012;18:22–28. doi: 10.1002/lt.22443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Netter JC, Cossarizza G, Narcy C, Hubert P, Ogier H, Revillon Y, et al. [Mid-term outcome of 2 cases with maple syrup urine disease: role of liver transplantation in the treatment] Arch Pediatr. 1994;1:730–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazariegos GV, Morton DH, Sindhi R, Soltys K, Nayyar N, Bond G, et al. Liver transplantation for classical maple syrup urine disease: long-term follow-up in 37 patients and comparative United Network for Organ Sharing experience. J Pediatr. 2012;160:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shellmer DA, DeVito DA, Dew MA, Noll RB, Feldman H, Strauss KA, et al. Cognitive and adaptive functioning after liver transplantation for maple syrup urine disease: a case series. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15:58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuang DT, Chuang JL, Wynn RM. Lessons from genetic disorders of branched-chain amino acid metabolism. J Nutr. 2006;136:243S–249S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna A, Hart M, Nyhan WL, Hassanein T, Panyard-Davis J, Barshop BA. Domino liver transplantation in maple syrup urine disease. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:876–882. doi: 10.1002/lt.20744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morioka D, Kasahara M, Takada Y, Corrales JP, Yoshizawa A, Sakamoto S, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for pediatric patients with inheritable metabolic disorders. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2754–2763. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flaschker N, Feyen O, Fend S, Simon E, Schadewaldt P, Wendel U. Description of the mutations in 15 subjects with variant forms of maple syrup urine disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:903–909. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0579-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Edenberg HJ, Crabb DW, Harris RA. Evidence for both a regulatory mutation and a structural mutation in a family with maple syrup urine disease. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1425–1429. doi: 10.1172/JCI114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McConnell BB, Burkholder B, Danner DJ. Two new mutations in the human E1 beta subunit of branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase associated with maple syrup urine disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1361:263–271. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4439(97)00046-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chuang DT, Ku LS, Kerr DS, Cox RP. Detection of heterozygotes in maple-syrup-urine disease: measurements of branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase and its components in cell cultures. Am J Hum Genet. 1982;34:416–424. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaleski LA, Dancis J, Cox RP, Hutzler J, Zaleski WA, Hill A. Variant maple syrup urine disease in mother and daughter. Can Med Assoc J. 1973;109:299–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuruta M, Mitsubuchi H, Mardy S, Miura Y, Hayashida Y, Kinugasa A, et al. Molecular basis of intermittent maple syrup urine disease: novel mutations in the E2 gene of the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex. J Hum Genet. 1998;43:91–100. doi: 10.1007/s100380050047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henneke M, Flaschker N, Helbling C, Muller M, Schadewaldt P, Gartner J, et al. Identification of twelve novel mutations in patients with classic and variant forms of maple syrup urine disease. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:417. doi: 10.1002/humu.9187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Krishnan VG, Mort ME, Xin F, Kamati KK, Cooper DN, et al. Automated inference of molecular mechanisms of disease from amino acid substitutions. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2744–2750. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neto JS, Carone E, Pugliese RP, Fonseca EA, Porta G, Miura I, et al. Modified pediatric end-stage liver disease scoring system and pediatric liver transplantation in Brazil. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:426–430. doi: 10.1002/lt.22000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morioka D, Takada Y, Kasahara M, Ito T, Uryuhara K, Ogawa K, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for noncirrhotic inheritable metabolic liver diseases: impact of the use of heterozygous donors. Transplantation. 2005;80:623–628. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000167995.46778.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]