Abstract

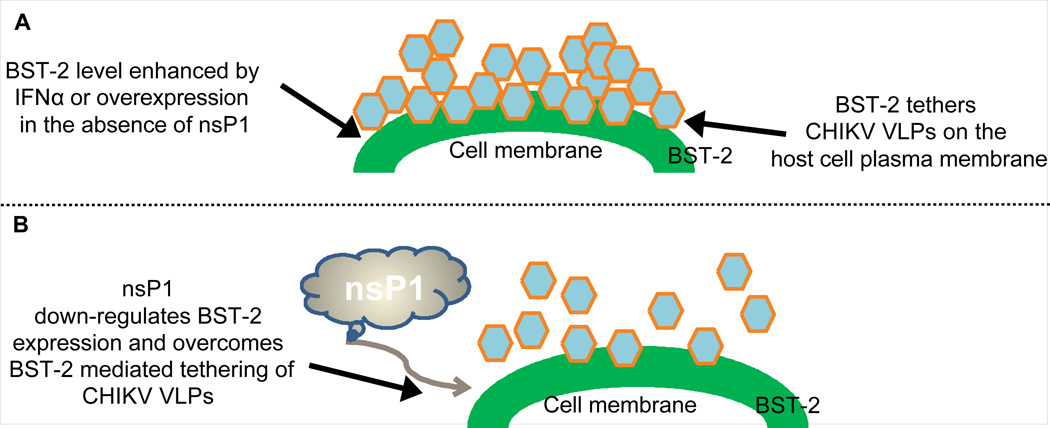

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a re-emerging alphavirus transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. Infection with CHIKV elicits a type I interferon response that facilities virus clearance, probably through the action of down-stream effectors such as antiviral IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). Bone marrow stromal antigen 2 (BST-2) is an ISG shown to restrict HIV-1 replication by preventing the infection of bystander cells by tethering progeny virions on the surface of infected cells. Here we show that enrichment of cell surface BST-2 results in retention of CHIKV virus like particles (VLPs) on the cell membrane. BST-2 was found to co-localize with CHIKV structural protein E1 in the context of VLPs without any noticeable effect on BST-2 level. However, CHIKV nonstructural protein 1 (nsP1) overcomes BST-2-mediated VLPs tethering by down-regulating BST-2 expression.. We conclude that BST-2 tethers CHIKV VLPs on the host cell plasma membrane and identify CHIKV nsP1 as a novel BST-2 antagonist.

Keywords: BST-2, CHIKV, E1, nonstructural protein, nsP1, SEM, tetherin, VLP

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an arboviral pathogen discovered in 1952 (Lumsden, 1955; Robinson, 1955) and transmitted to humans by infected mosquitoes, usually Aedes aegypti and recently Aedes albopictus. Additionally, there is evidence for mother to fetal transmission (Gerardin et al., 2008). Interest in CHIKV has grown following the 2005 outbreaks in Asia (Schuffenecker et al., 2006). Infection with CHIKV is now the cause of many human epidemics in different parts of the world including Africa, Asia, and Europe. Infected patients present with many symptoms including fever, severe arthralgia, myalgia, headaches, nausea, and vomiting (Lahariya and Pradhan, 2006).

CHIKV is a positive, single-stranded RNA virus whose genome is composed of two open reading frames (ORFs) with genomic organization arranged in: “5′-nsP1-nsP2-nsP3-nsP4-(junction region)-C-E3-E2-6K-E1-poly (A)-’3”. ORF2 encodes structural proteins consisting of capsid (C) and the two membrane-bound envelope glycoproteins proteins E2 and E1. ORF1 encodes non-structural proteins (nsPs) 1, 2, 3 precursor, and nsP4 that are translated from the viral genomic RNA. Alphavirus nsPs have different functions. nsP4 functions as the RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp)(Hahn et al., 1989a) and could also play a scaffolding role for interaction with other nsPs or host proteins through its N-terminus(Shirako et al., 2000). The N-terminus of nsP3 possesses ADP-ribose 1-phosphate phosphatase and RNA-binding activity(Malet et al., 2009) in addition to its role in modulating pathogenicity in mice(Park and Griffin, 2009; Tuittila and Hinkkanen, 2003). While nsP2 exhibits RNA triphosphatase/nucleoside triphosphatase and helicase activities within its N-terminal domain(Gomez de Cedron et al., 1999; Vasiljeva et al., 2000), the C-terminus encodes the viral cysteine protease necessary for processing of nonstructural polyprotein(Hahn et al., 1989b; Hardy and Strauss, 1989). nsP1 N terminal region is a methyltransferase and guanylyltransferase involved in capping and methylation of newly synthesized viral genomic and subgenomic RNAs(Ahola and Kaariainen, 1995). Moreover, nsP1 is a major component of the virus replicase complex(Salonen et al., 2003) and functions to anchor replication complexes to host cellular membranes during RNA replication(Peranen et al., 1995).

After a 2 to 4 days incubation period following virus entry via receptor-mediated endocytosis (Cho et al., 2008; Leung et al., 2011; Voss et al., 2010), CHIKV replicates in the skin and then spreads to other organs (Couderc et al., 2008; Her et al., 2010; Morrison et al., 2011). Upon infection by viruses, host cells employ various defensive mechanisms collectively called host restriction factors (HRFs) to thwart virus replication. For example, BST-2 is a type II membrane, interferon-inducible protein (Neil et al., 2008). Cell surface expression of BST-2 tethers nascent enveloped viruses on the cell surface preventing their egress. Some of the viruses susceptible to BST-2 are human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 (HIV- and HIV-2), murine leukemia virus (MLV), mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV), and Ebola virus (Goffinet et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2012a; Lopez et al., 2010; Neil et al., 2008). Although BST-2 blocks virus release, most viruses such as HIV-1 and HIV-2 have evolved distinct mechanisms to overcome BST-2 inhibitory effects. For example, the HIV-1 accessory protein Vpu and HIV-2 envelope protein counteract BST-2 antiviral activity enabling enhanced virus release (Bartee et al., 2006; Hauser et al., 2010; Van Damme et al., 2008). Ebola glycoprotein also antagonizes BST-2 with a resultant increase in virus release (Kaletsky et al., 2009). However, it’s unclear whether HRFs such as APOBEC3 (Bishop et al., 2004; Goila-Gaur et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2012b; Low et al., 2009; Mehta et al., 2012; Okeoma et al., 2010; Okeoma et al., 2007; Okeoma et al., 2009a; Okeoma et al., 2009b; Suspene et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2004) and BST-2/Tetherin (Jones et al., 2012a; Le Tortorec et al., 2011; Neil et al., 2008; Ruiz et al., 2010; Zhang and Liang, 2010) documented for restricting retrovirus replication are relevant for CHIKV replication and pathogenicity.

Given that type I IFN and interferon stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) play a role in blocking CHIKV replication (Couderc et al., 2008; Schilte et al., 2010; Werneke et al., 2011) and CHIKV nsP2 inhibits IFN-signaling (Fros et al., 2010), we hypothesize that the IFNα-inducible BST-2 prevents budding of CHIKV VLPs. Our results show that in the presence of BST-2, CHIKV VLPs are retained on the cell membrane. Indeed, while both E1 and nsP1 co-localize with BST-2, only nsP1 down-regulates BST-2 expression and diminishes VLP tethering. We therefore conclude that CHIKV nsP1 has evolved to antagonize BST-2.

Results

Effects of BST-2 on nascent CHIKV VLPs

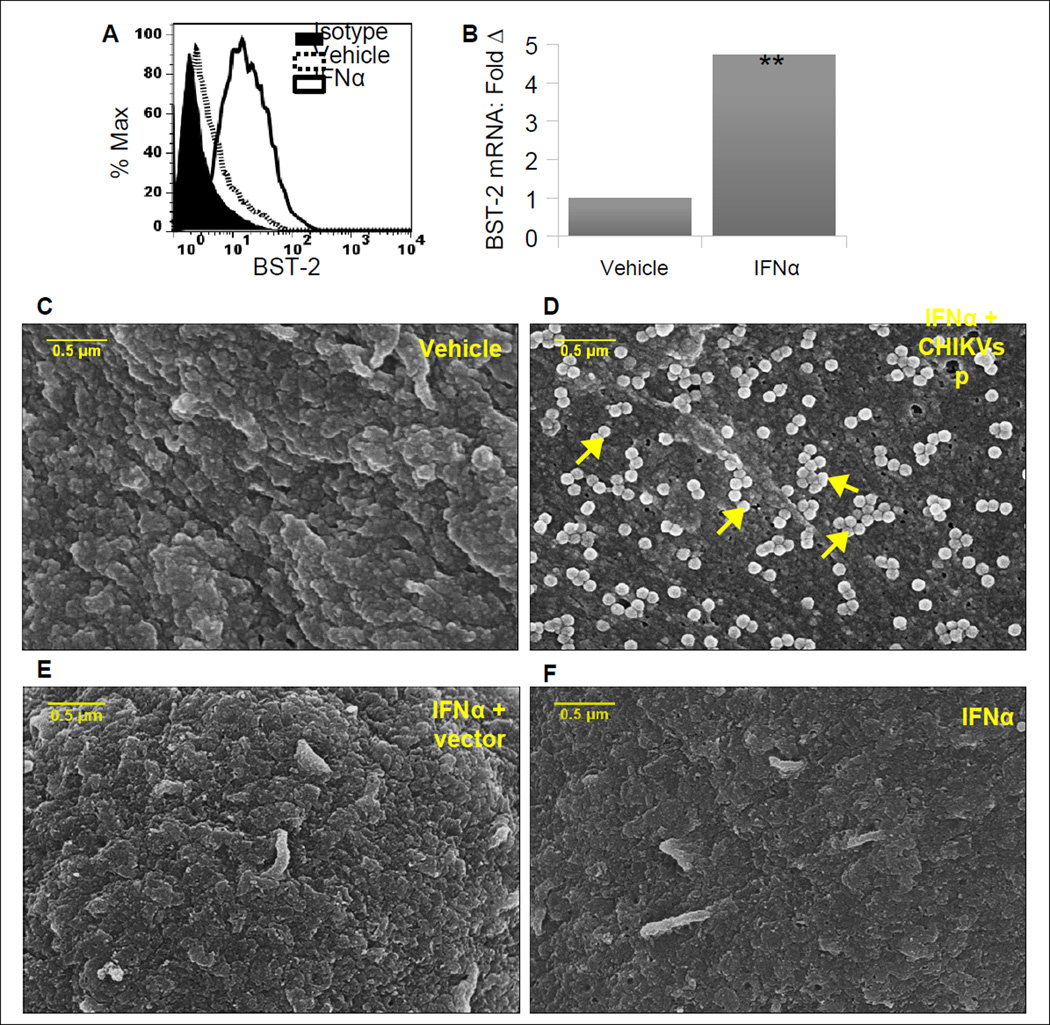

BST-2 is an IFNα-responsive gene whose expression increases with increasing amounts of IFNα. Previous studies by others and our group have shown that BST-2 retains viruses and VLPs at the surface of infected or transfected cells (Jones et al., 2012a; Neil et al., 2008). Specifically, we showed that treatment of cells with IFNα enhanced endogenous BST-2 expression with a resultant tethering of MMTV particles (Jones et al., 2012a). Since CHIKV is highly responsive to IFNα, we hypothesized that IFNα-induced BST-2 will retain CHIKV VLPs on the cell surface. We induced endogenous BST-2 in 293T cells by treatment with IFNα. 293T cells express low levels of BST-2 that is inducible by IFNα (Neil et al., 2008). Treatment of cells with IFNα increased cell surface BST-2 levels as judged by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) compared to vehicle-treated cells (Figure 1A). Similar observation was made in level of BST-2 mRNA using RT-qPCR (Figure 1B). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of vehicle treated cells reveal little or no cell surface associated VLPs (Figure 1C). However, cells treated with IFNα have numerous accumulations of VLPs associated with the plasma membrane (Figure 1D). No major differences in cell morphology were observed in all treatment conditions (Figures 1C to 1F). However, cells treated with IFNα have few electron dense structures on the surface.

Figure 1. IFNα-induced BST-2 tethers CHIKV VLPs on the cell membrane.

293T cells were stimulated with vehicle or 1000 units/ml of recombinant IFNα prior to transfection with constructs expressing CHIKV structural proteins (CHIKVsp). (A, B) FACS and RT-qPCR analysis showing that IFNα enhanced level of BST-2 expression; (C) SEM of vehicle treated cells; (D) SEM of IFNα-stimulated CHIKVsp-transfected cells showing budding VLPs retained on the cell surface - arrow heads; (E) SEM of IFNα-stimulated empty vector-transfected cells; (F) SEM of IFNα-stimulated cells. PCR data is normalized to GAPDH and presented as fold change relative to IFNα-treated cells. Error bars are standard deviation; ** is significance with p value less than 0.01. Representative of 3 experiments is shown.

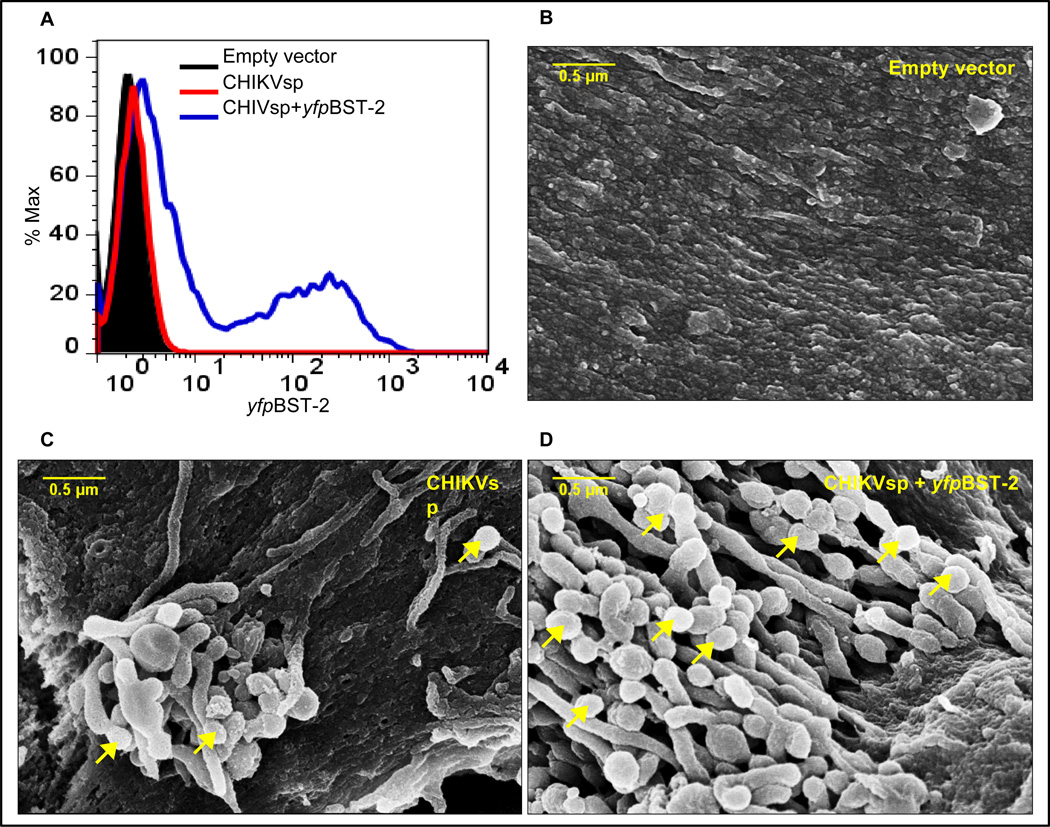

To validate the above finding, we used transient transfection of plasmids expressing CHIKV structural proteins (CHIKVsp) or in combination with yfpBST-2 in 293T cell line. Following transfection, cells were examined for level of surface BST-2 expression by FACS. As expected, BST-2 was present on the cell surface following transfection (Figure 2A). Next, cells were subjected to SEM. While VLPs were not observed in cells transfected with empty vector (Figure 2B), a few buds of approximately 100 to 200 nm in size were present in cells transfected with CHIKVsp construct (Figure 2C). In contrast, numerous newly budded VLPs were observed tethered on the surface of cells transfected with CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 (Figure 2D). These observations are similar to findings made with HIV (Neil et al., 2008), influenza virus (Mangeat et al., 2012), and MMTV (Jones et al., 2012a), and indicate that BST-2 tethers CHIKV VLPs on the cell membrane. Unlike in cells treated with IFNα, cells transfected with BST-2 (Figure 2D) have higher number of electron dense structures that appear to be connecting VLPs; however the identity of these structures was not examined. In the above experiments, we observed little or no VLP budding from vehicle treated cells or cells lacking BST-2. It is possible that the absence of budding virions in cells that lack BST-2 is due to the speed or frequency of budding events. It is worth noting that our SEM data were acquired 24 hours after IFNα treatment and transfections.

Figure 2. Ectopically expressed BST-2 retains BST-2 on the cell surface.

293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing CHIKVsp or CHIKVsp and yfpBST-2. Cells were examined for BST-2 levels based on yfp expression and subjected to SEM analysis. Figure shows: (A) FACS analysis of BST-2 level after transfection; (B) SEM of empty vector transfected cells; (C) CHIKVsp transfected cells; and (D) SEM of CHIKVsp+ yfpBST-2 transfected cells. Arrow heads point to retained VLPs. The scale bar represents 0.5µm. Figure is representative of 3 experiments.

CHIKV structural proteins co-localize with BST-2 when expressed in the context of VLPs

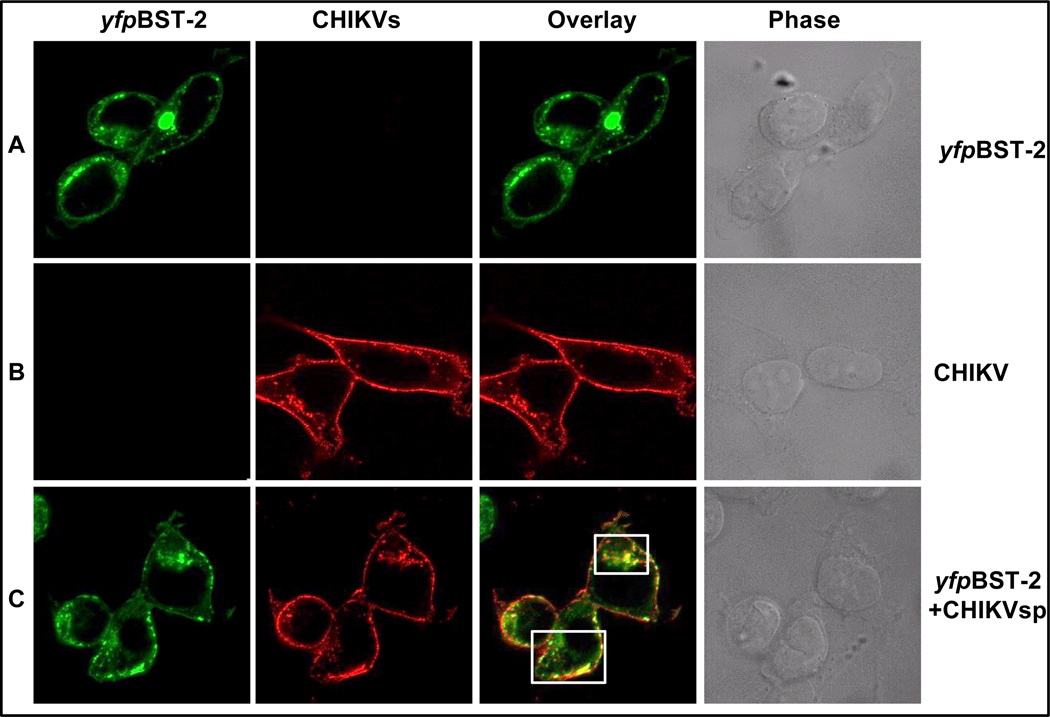

Given that BST-2 restricts budding of CHIKV VLPs, we next examined whether BST-2 could localize with CHIKV structural proteins and which structural protein is involved. For this purpose, 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing yfpBST-2 and untagged CHIKVsp. Cells were incubated with CHIKV polyclonal antibody 24 hours after transfection. Co-localization analyses were performed with confocal microscopy. BST-2 was detected primarily at the plasma membrane, with some accumulations at intracellular sites (Figure 3A). Similar to BST-2, CHIKV protein was also present at the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments (Figure 3B). Co-localization of BST-2 with CHIKVsp occurred both at the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments (Figure 3C). Additionally, we observed characteristic puncta likely to represent nascent VLPs. BST-2 co-localized extensively with these puncta (Figure 3C). BST-2 is directly incorporated into HIV virions (Fitzpatrick et al., 2010) and the localization of BST-2 with CHIKV puncta could mean that BST-2 is encapsidated into CHIKV VLPs. We observed no obvious effect on BST-2 levels or CHIKVsp distribution in cells co-expressing these proteins.

Figure 3. CHIKV structural proteins co-localize with BST-2 in the context of VLP.

Plasmids expressing CHIKVsp and/or yfpBST-2 were transfected alone or together into 293T cells. Figure illustrates: (A) Confocal analysis of yfpBST-2 expression; (B) analysis of CHIKV expression in CHIKVsp transfected cells; and (C) Confocal examination of co-localization between yfpBST-2 and CHIKVsp. yfpBST-2 is in green, CHIKV is in red, and merge is in orange. Specificity of the anti-CHIKV antibody is demonstrated in the first panel in row B. Images were taken at 63×. White boxes highlight areas of co-localization. Figure is representative of experiments repeated 4 times.

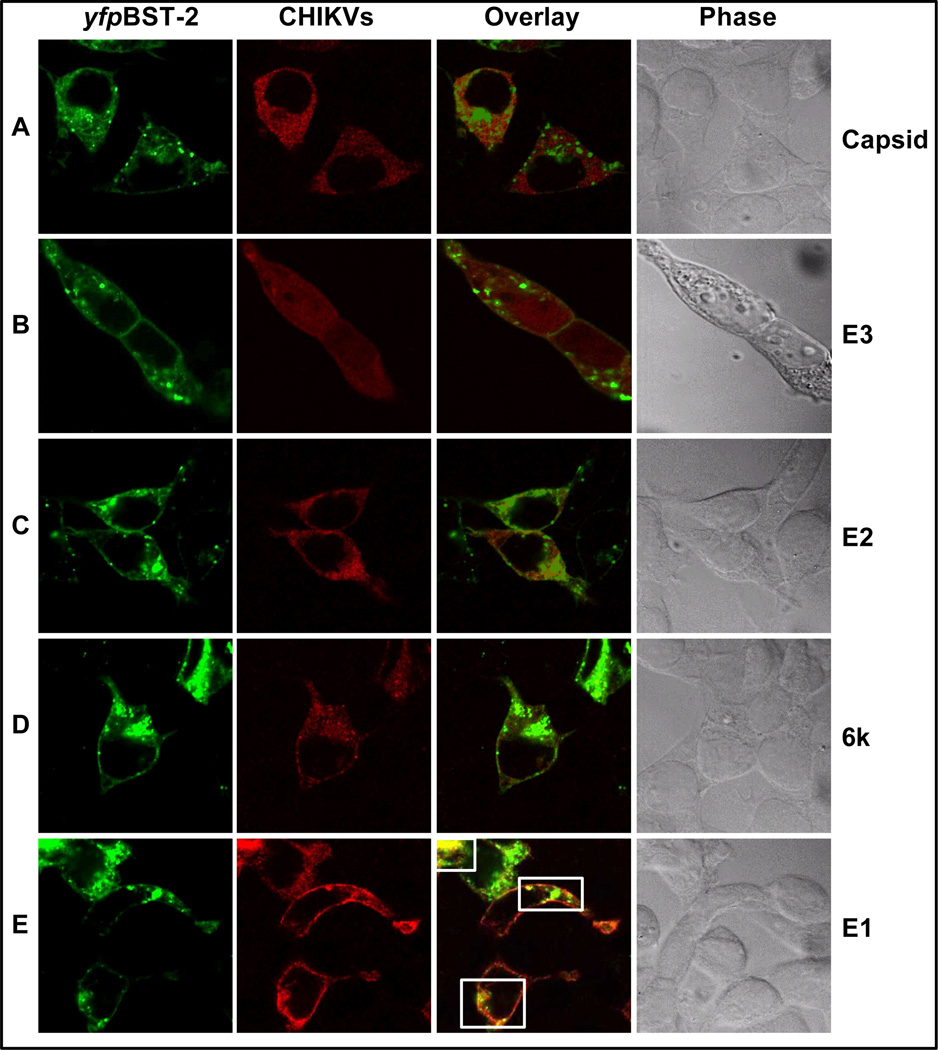

E1 is the CHIKV structural protein that co-localizes with BST-2

The preceding data show that a component of CHIKV structural protein co-localizes with BST-2. We postulated that the E1 glycoprotein is the CHIKV protein that co-localizes with BST-2. 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing yfpBST-2 and various plasmids expressing mCherry tagged CHIKV structural proteins. Twenty-four hours later, cells were analyzed for co-localization by confocal microscopy. Co-localization was not observed in cells co-transfected with BST-2 and Capsid, E3, E2, or 6k proteins (Figures 4A to 4D). As expected, substantial co-localization was observed between BST-2 and E1 proteins (Figure 4E). The observation that E1 glycoprotein co-localizes with BST-2 is in agreement with previous studies which showed that retroviral envelope proteins co-localize with BST-2 (Jolly et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2012a). However, the significance of this co-localization is unknown.

Figure 4. CHIKV E1 glycoprotein is the structural protein that co-localize with BST-2.

mCherry tagged plasmids expressing various structural proteins of CHIKV and yfpBST-2 were cotransfected into 293T cells. (A to E) is confocal microscopic analysis showing expression of CHIKV structural proteins and yfpBST-2, and co-localization between the two proteins. yfpBST-2 is in green, CHIKV is in red, and merge is in orange. Images were taken at 63×. White boxes highlight areas of co-localization. Figure is representative of experiments repeated several times.

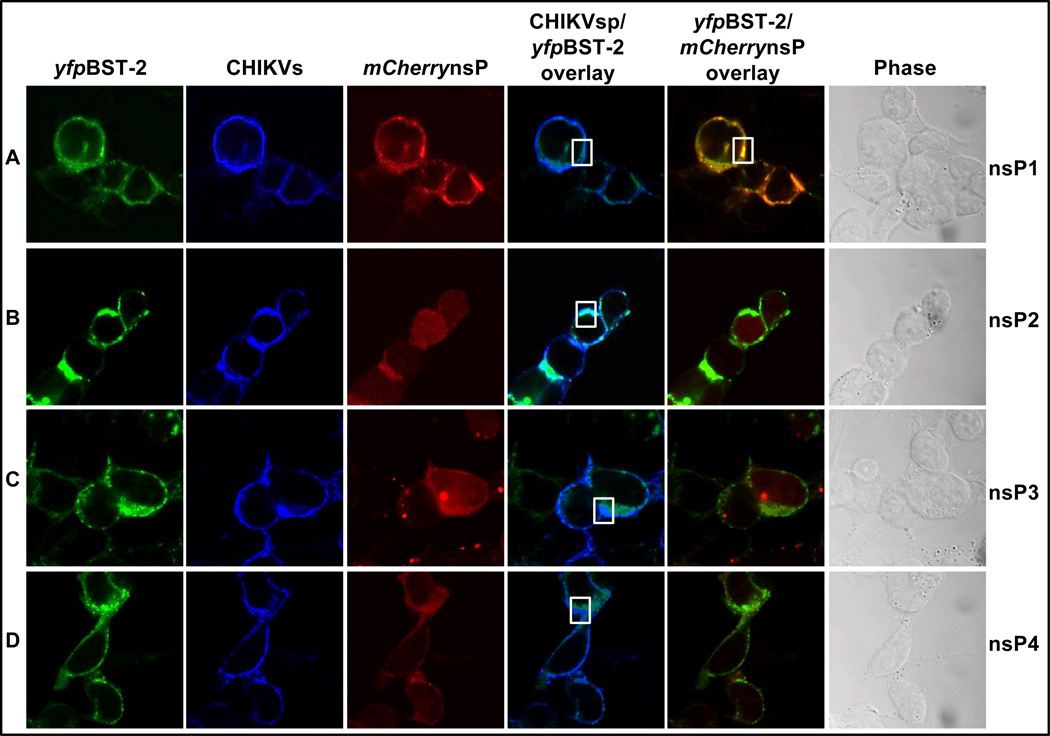

CHIKV nsP1 co-localizes with BST-2

The alphavirus nonstructural proteins, nsPs, are essential for replication (Leung et al., 2011). Since the construct expressing CHIKV VLP protein lacks the nsP component of the viral protein, we set out to determine whether CHIKV nsPs co-localize with BST-2 in the context of VLPs. 293T cells were co-transfected with various plasmids expressing yfpBST-2, untagged CHIKVsp, and different mCherry tagged CHIKV nsPs. Cells were examined for co-localization twenty four hours later as described above. BST-2 was observed to co-localize with CHIKVsp in the presence of different nsPs (Figures 5A to 5D). However, while there are many co-localization points between CHIKVsp and BST-2 in the presence of nsPs 2 to 4 (Figures 5B to 5D), the level of co-localization between CHIKVsp and BST-2 in the presence of nsP1 is reduced (Figure 5A). In sharp contrast, only nsP1 co-localized with BST-2 in the context of VLPs (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. CHIKV nsP1 co-localizes with BST-2 in the context of VLP.

293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing CHIKVsp and yfpBST-2 together with various mCherry tagged nonstructural proteins. (A to D) is confocal images showing expression of yfpBST-2, CHIKVsp, mCherrynsPs, and overlays of CHIKV/yfpBST-2 (turquoise) and yfpBST-2/mCherrynsPs (orange). CHIKVsp is in blue, yfpBST-2 is in green, mCherrynsP is in red. Images were taken at 63×. White boxes highlight areas of co-localization. Figure is representative of 4 experiments.

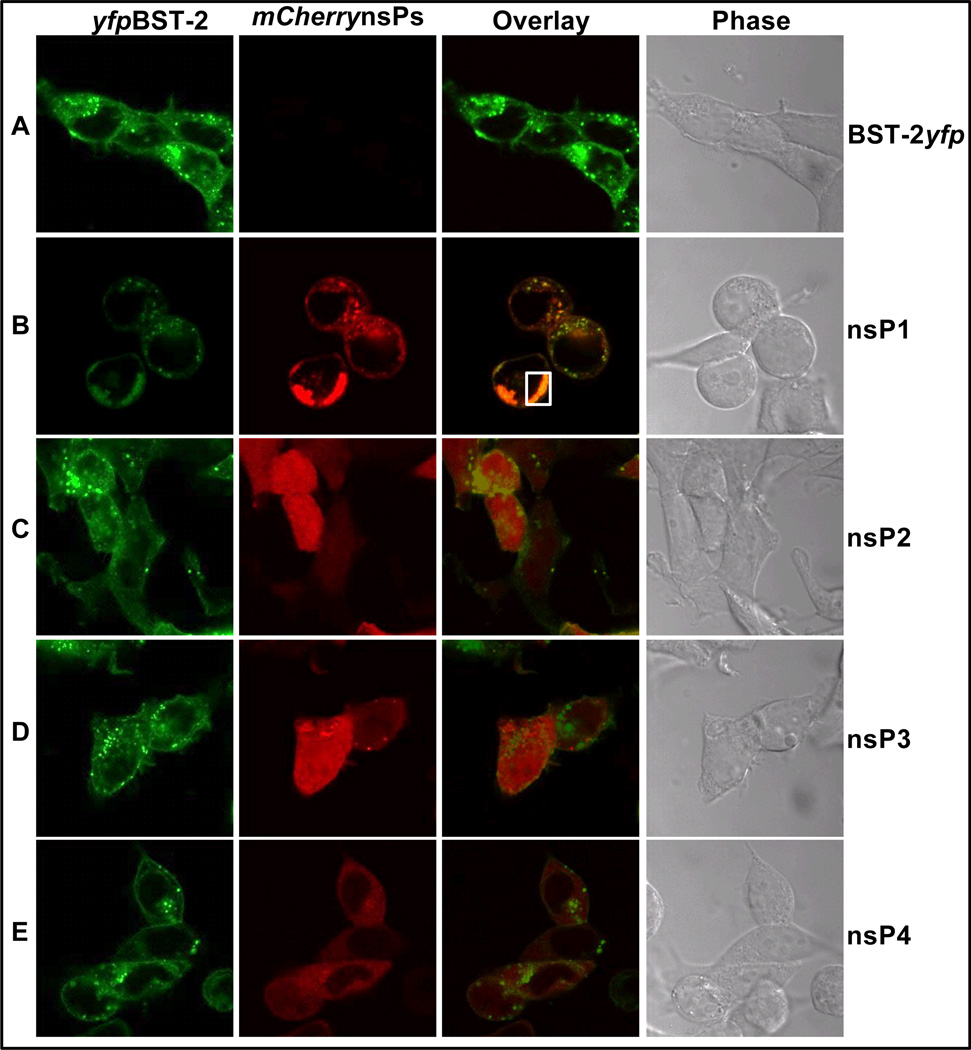

Next, we examined if CHIKV nsP1 alone co-localizes with BST-2. Hence, 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing yfpBST-2 and different mCherry tagged CHIKV nsPs. Cells were examined by confocal microscopy for co-localization. BST-2 was observed on the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments (Figure 6A). As expected, only nsP1 co-localized with BST-2 (Figure 6 B) while co-localization was not observed with nsP2, nsP3, or nsP4 (Figures 6C to 6D). This result is in agreement with the finding in figure 5. Furthermore, expression of nsP1 had no effect on cell viability (not shown). This observation supports a previous report that nsP1 expressed alone is stable and had no impact on cell viability(Kiiver et al., 2008).

Figure 6. CHIKV structural protein is not required for nsP1 to co-localize with BST-2.

mCherry tagged plasmids expressing various nsPs were cotransfected with yfpBST-2 into 293T cells. (A to E) is confocal images depicting expression of yfpBST-2, mCherrynsPs, and overlays of yfpBST-2/mCherrynsPs (orange). yfpBST-2 is in green, mCherrynsP is in red. Images were taken at 63×. White boxes highlight areas of co-localization. Figure represents experiments repeated multiple times.

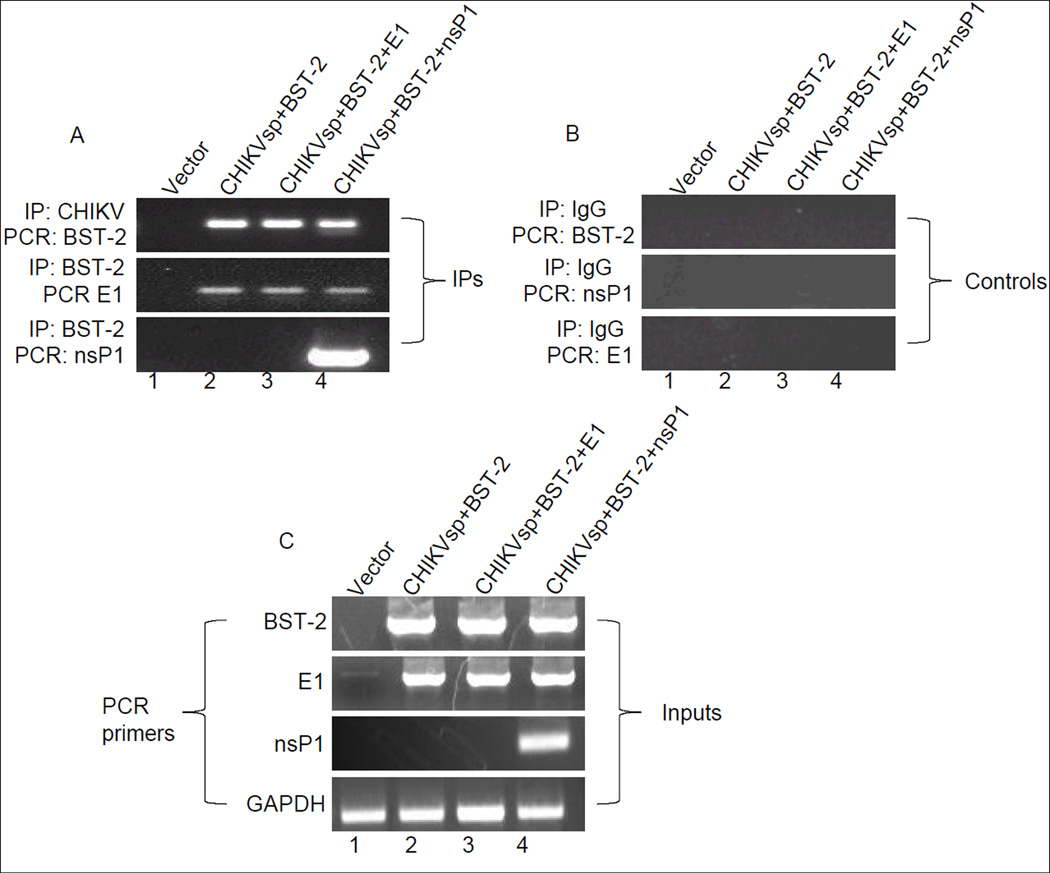

CHIKV proteins interact with BST-2 mRNA

Since both CHIKV E1 and nsP1 proteins co-localize with BST-2, we thought that these proteins may also associate with BST-2. We examined this hypothesis by performing RNA immunoprecipitation (RNA-IP) and RT-PCR analysis in 293T cells transfected with mouse yfpBST-2 only, CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2, CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 + E1, and CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 + nsP1. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and sonicated. Equal amounts of proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-BST-2 and anti-CHIKV at 4°C overnight. Protein A/G agarose was added to the protein complex for 2 hours, and protein-RNA complexes were pulled down by centrifugation. RNA was extracted with TRIzol and 20µg reverse transcribed into cDNA. Equal concentrations of cDNA were used for RT-PCR with primers specific to BST-2, E1, or nsP1 (Figure 7A). Interestingly, antibody against CHIKV efficiently precipitated BST-2 and anti-BST-2 efficiently pulled CHIKV E1 and nsP1 down (Figure 7A lanes 2, 3, 4). As a control for nonspecific precipitation, unrelated IgG anti-serum was used for immunoprecipitation and no PCR product was observed with primers specific to BST-2, E1, and nsP1 (Figure 7B). Comparison of IP products (Figure 7A) with the input lanes (Figure 7C) suggests that more nsP1 is in complex with BST-2 compared to E1. Together, these results demonstrate a specific interaction between BST-2 and CHIKV E1 and nsP1. Although more nsP1 was determined to be in complex with BST-2, we nonetheless detected interaction between BST-2 and E1.

Figure 7. RNA-IP of BST-2 and CHIKV mRNA in 293T cells.

RNAs isolated from 293T cells transfected with empty vector, CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2, CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 + mCherry E1, and CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 + mCherrynsP1 were immunoprecipitated by anti-BST-2 and anti-CHIKV depending on experiment. (A) Immunoprecipitated RNAs were detected by RT-PCR using primers specific for BST-2, E1, and nsP1; (B) RNAs immunoprecipitated with unrelated IgG were used as controls and PCR amplified with BST-2, E1, and nsP1; (C) Input RNA and GAPDH were detected with relevant primers. Input RT-PCRs were performed with total RNA extracts without IP. IP indicates that the RT-PCRs were performed with the RNAs that were immunoprecipitated with relevant antibody. IP = immunoprecipitation.

CHIKV nsP1 but not E1 overcomes BST-2-mediated tethering of CHIKV VLPs

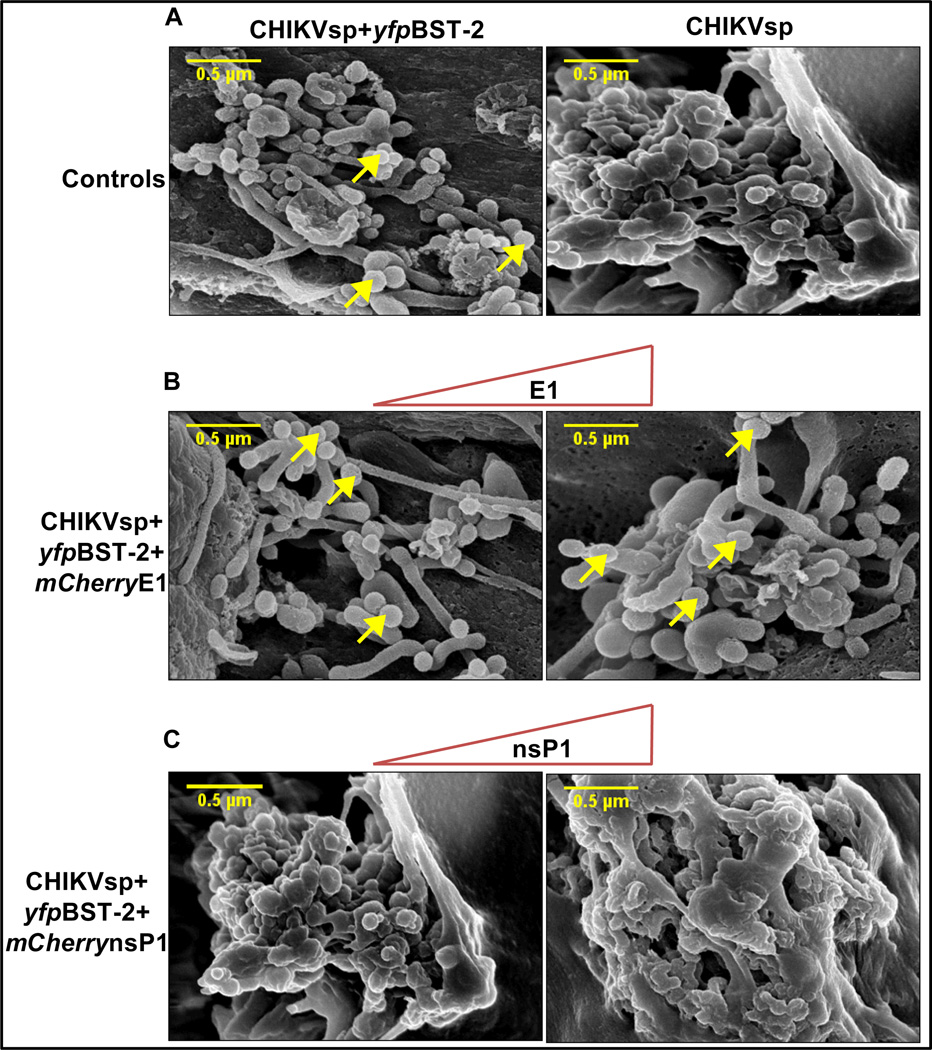

It is well established that viral proteins such as the HIV-1 accessory protein Vpu antagonizes BST-2 (Mangeat et al., 2009; Neil et al., 2008). In other viral systems, the viral env may also counteract tethering activity of BST-2 (Kaletsky et al., 2009). Since CHIKV E1 and nsP1 co-localize (Figures 4E and 5A) and interact (Figure 7A) with BST-2, we hypothesized that one of these proteins will antagonize BST-2-mediated VLP tethering. 293T cells were transfected with a constant amount of CHIKVsp and/or yfpBST-2 to induce VLP formation, and with different concentrations of plasmids expressing mCherryE1, or mCherrynsP1. Cells were subjected to SEM to determine whether VLPs are present on the cell plasma membrane in the presence of BST-2. As anticipated, BST-2 retained CHIKV VLPs on the cell plasma membrane (Figure 8A). The addition of excess E1 protein (considering that CHIKVsp contains E1) did not rescue BST-2 mediated tethering of VLPs (Figure 8B), but rather increased the number of VLPs retained on the cell surface (Figures 8B). Interestingly, addition of nsP1 counteracted BST-2-mediated retention of CHIKV VLPs (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. nsP1 overcomes BST-2 mediated CHIKV VLP tethering.

293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing CHIKVsp, CHIKVsp+yfpBST-2, and varying amounts of E1 or nsP1 at CHIKVsp:E1/nsP1 ratios of 1:1 and 1:2.5 µg. Cells were examined for BST-2 levels (not shown) and subjected to SEM analysis. (A) SEM of Control cells; (B) SEM of cells transfected with CHIKVsp and increasing concentration of E1; (C) SEM of cells transfected with CHIKVsp and increasing concentration of nsP1. The scale bar represents 0.5 µm. Arrow heads point to retained VLPs. Figure is representative of experiments repeated several times.

Next we semi-quantitatively evaluated the differences in CHIKV VLPs tethered to the membrane of 293T cells by TEM analysis using a previously described protocol (Pease et al., 2009). The experiment above was repeated with 293T transfected with CHIKVsp alone, CHIKVsp + BST-2, CHIKVsp + BST-2 + E1, and CHIKVsp + BST-2 + nsP1. Individual cells were magnified five thousand fold and subjected to semiquantitative analysis of non-overlapping tethered VLPs (Figure 9, Table 1). As expected, cells transfected with CHIKV alone retained few VLPs on the cell membrane but in the presence of BST-2 the number of CHIKV VLPs tethered to the cell surface is tripled compared to CHIKV alone (Figures 9A, 9B, and Table 1). The number of VLPs tethered to the cell surface in the presence of CHIKV BST-2 and E1 (Figure 9C, table 1) is comparable to the number of VLPs observed with CHIKV and BST-2, which indicates that the E1 protein does not have a significant effect on the ability of BST-2 to tether VLPs to the membrane. However, the ability of BST-2 to tether CHIKV VLPs to the cell surface is significantly diminished in the presence of nsP1 (Figure 9D, table 1), suggesting that nsP1 has a negative and specific effect on BST-2 mediated tethering of CHIKV VLPs. These results indicate that BST-2 functions to retain CHIKV VLPs on the cell surface while nsP1 removes cell surface associated VLPs. Importantly, the nsP1 effect was dose dependent (Figures 8C). Overall, our data suggest that CHIKV nsP1 is a BST-2 antagonist.

Figure 9. Mean tethered CHIKV VLPS per TEM field.

TEM images of individual cells magnified five thousand fold for semiquantitative analysis of non-overlapping CHIKV VLPs tethered to the surface of 293T cells. (A) CHIKVsp alone; (B) CHIKVsp + BST-2; (C) CHIKVsp + BST-2 + E1; and (D) CHIKVsp + BST-2 + nsP1.

Table 1.

Semi-quantitative analysis of CHIKV VLP numbers from TEM images

| Sample ID | VLP numbers | p = 0.0274 | ||||||

| Field 1 | Field 2 | Field 3 | Field 4 | Total VLPs |

Mean VLPs per Field |

SD | ||

| CHIKV | 52 | 451 | 85 | 582 | 1170 | 292.5 | 264.5 | |

| CHIKV+BST-2 | 1043 | 510 | 413 | 1587 | 3553 | 888.25 | 542 | |

| CHIKV+BST-2+E1 | 377 | 314 | 890 | 1162 | 2743 | 685.75 | 409.1 | |

| CHIKV+BST-2+nsP1 | 58 | 48 | 31 | 50 | 187 | 46.75 | 11.35 | |

CHIKV nsP1 but not E1 down-regulates BST-2

Different viruses have evolved to counteract the antiviral activity of BST-2 through mechanisms that include down-regulation of cell surface BST-2 expression. Given that E1 and nsP1 interact and co-localize with BST-2 but nsP1 diminishes BST-2-mediated VLP tethering, we examined whether nsP1 counteracts BST-2 effect by down-modulating its expression. We subjected the same cells described above in figures 8A and 8B to FACS analysis and confocal microscopy to determine level of BST-2 expression. FACS examination of surface BST-2 protein level reveals that increasing amounts of E1 plasmid enhanced BST-2 protein levels from mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 72.2 +/− 1.13 to 98.3+/− 0.42 (Fig. 10A bars). However, increasing nsP1 concentration reduced BST-2 protein levels from MFI of 46.95+/− 4.88 to 31.55+/− 1.77 (Fig. 10B bars). While E1 only co-localized with BST-2 at high concentration (Figure 10C) nsP1 co-localized with BST-2 at both high and low concentrations (Figure 10D). Close examination of BST-2 levels reveal that nsP1 (Figure 10D, Table 2) but not E1 (Figure 10C, Table 2) reduced the level of BST-2 in a concentration dependent manner, supporting the FACS data (Figure 10B). Similar observation was made at the transcript level upon evaluation of BST-2 mRNA expression in cells transfected with BST-2 alone, CHIKVsp + BST-2, CHIKVsp + BST-2 + E1, and CHIKVsp + BST-2 + nsP1. Although CHIKVsp alone or with E1 had no impact on BST-2 mRNA, expression of nsP1 significantly reduced BST-2 mRNA (Figure 10E, bar and gel). Since both the confocal (Figure 10D) and RT-qPCR (Figure 10E) data respectively show down-regulation of BST-2 protein and mRNA in the presence of nsP1, we think that CHIKV nsp1 could be involved in BST-2 degradation.

Figure 10. CHIKV nsP1 suppresses BST-2 expression.

CHIKVsp, mCherry tagged plasmids expressing E1 or nsP1, and yfpBST-2 were transfected or cotransfected into 293T cells. Figure shows: (A and B) FACS analysis showing level of surface yfpBST-2 upon co-transfection of CHIKV and E1 (A) or CHIKV and nsP1 (B). The bars are mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) while the histograms (inset) represent percent expression; (C) confocal images depicting expression levels of yfpBST-2, mCherryE1, and overlay of yfpBST-2/mCherryE1; (D) confocal images showing expression levels of yfpBST-2, mCherrynsP1, and overlay of both; (E) BST-2 mRNA levels following transfection with different CHIKV constructs. PCR data is normalized to GAPDH and presented as fold change relative to BST-2 transfected cells. Error bars are standard deviation; * is significance with p value less than 0.05.White boxes highlight areas of co-localization. Figure represents experiments repeated severally with similar results.

Table 2.

Quantitative analysis of confocal images for BST-2, E1, and nsP1

| Sample ID | Mean Intensity (BST-2) |

SD | p = 0.0401 | Mean Intensity (nsP1/E1) |

SD |

| BST-2 only | 7.34E+07 | 7093500.33 | n/a | n/a | |

| CHIKV+BST-2 | 6.97E+07 | 1100000.15 | n/a | n/a | |

| CHIKV+BST-2+E1ratio 1:1 | 6.02E+07 | 924020.36 | 4.30E | 3.59 | |

| CHIKV+BST-2+E1ratio 1:2.5 | 8.17E+07 | 5859314.26 | 8.18E | 13.19 | |

| CHIKV+BST-2+nsP1ratio 1:1 | 3.72E+07 | 8601123.39 | 4.07E | 8.02 | |

| CHIKV+BST-2+nsP1ratio 1:2.5 | 2.91E+07 | 7797246.70 | 7.77E | 11.18 |

Discussion

Here we demonstrate that BST-2 tethers CHIKV VLPs on the cell membrane in the absence of nsP1 and its expression is down-regulated by nsP1 with a concomitant reduction of tethered VLPs. This observation reiterates the characteristic function of BST-2 restriction of retroviruses described previously by us and others (Jones et al., 2012a; Neil et al., 2008). BST-2 co-localized with CHIKV E1 and nsP1 both on the cell membrane and the intracellular compartments. With nsP1, the co-localization correlates with suppressing BST-2 protein levels with increasing concentration of nsP1. Moreover, the observation that more nsP1 is in complex with BST-2 compared to E1 may be indicative of the affinity between BST-2 and nsP1. The fact that significant VLPs were retained on the cell surface and that nsP1 is required to bypass retention by BST-2 illustrates that this antiviral protein is capable of preventing alphavirus release and spread.

Our studies therefore provide an important model with analogies drawn to HIV-1 Vpu-mediated BST-2 antagonism. The effect of CHIKV nsP1 on VLP retention and BST-2 expression can be compared to that of HIV-1 Vpu in that both repress BST-2 (Dube et al., 2010a; Dube et al., 2010b) and diminish the retention of VLPs on the cell membrane (Neil et al., 2008).

In our studies, we observed some electron-dense structures that seem to be connected to VLPs especially in cells transfected with BST-2. Although the identity of these structures was not examined, they seem to be more noticeable with the addition of exogenous BST-2 (Fig. 2D and 8B) but less noticeable in cells transfected with CHIKVsp (Fig. 2C and 8C). It is possible that these electron-dense structures may represent multiple BST-2 molecules bridging retained CHIKV VLPs. Indeed, it has previously been shown that BST-2 forms a physical bridge between HIV-1 virions and the host plasma membrane (Hammonds et al., 2010). These authors observed BST-2 positive filamentous structures demonstrated in cells infected with HIV-1. Furthermore, BST-2 functions as a physical link between lipid rafts and the apical actin cytoskeleton at least in polarized epithelial cells (Rollason et al., 2009). We are not aware of any studies that has examined the impact of CHIKV nsP1 on host cell morphology, however, nsP1 protein of other alphaviruses - Semliki Forest virus and Sindbis virus have been shown to cause rearrangement of actin filaments (Laakkonen et al., 1998). Thus, the absence or apparent disappearance of the electron-dense structures in cells transfected with nsP1 (Figure 8C) could mean that components of CHIKV in general and nsP1 in particular may disrupt the formation of these structures, by rearranging the actin cytoskeleton and disrupting BST-2. Disruption of these electron-dense structures could then result in release of more VLPs, especially if these VLPs are contained within the structure. Further studies will investigate this observation.

Our studies also provide compelling justification for efforts to develop BST-2-mediated therapeutics that will target a spectrum of viruses including alphaviruses. The novel finding that an alphavirus nsP1 antagonizes BST-2 by down-regulating its expression provides a unique opportunity to better understand the mechanisms of BST-mediated inhibition of virus release. While there is paucity of knowledge on the role of alphavirus nsPs, Kiiver et al., 2008 demonstrated that expression of Semliki Forest virus (SFV) nsP1 suppressed genomic RNA synthesis and reduced virus yield (Kiiver et al., 2008), while Chu and his group showed that expression of CHIKV E1 and nsP1 in the form of shRNA blocked CHIKV replication (Lam et al., 2012). In general, alphavirus nsPs control the transcription of minus-strand (synthesized only at early stages of infection) and plus-strand (made throughout infection) RNAs. In particular, alphavirus nsP1 is a major component of the virus replicase complex (Shirako and Strauss, 1994). Both nsP1 and nsP4 catalyze the initiation and continuation of negative-strand RNA synthesis (Mi et al., 1989). Like in other alphaviruses, CHIKV nsP1 is a palmitoylated 535 amino acid protein (Solignat et al., 2009). Palmitoylation allows nsP1 of the prototypic alphaviruses SFV to tightly associate with membranes (Laakkonen et al., 1996). Additionally, nsP1 palmitoylation plays a role in viral pathogenesis since palmitoylation-defective SFV was rendered apathogenic in mice and their mutant viruses produced uninfectious virus in the brain (Ahola et al., 2000). Interestingly, these mutant viruses failed to produce plaques in HeLa cells known for high level of endogenous BST-2 (Neil et al., 2008).

Furthermore, since the expression of BST-2 in nonhematopoietic and hematopoietic cells is induced by IFNα (Jones et al., 2012a; Neil and Bieniasz, 2009), our studies show that upon enhancement of BST-2 with IFNα, CHIKV VLPs were retained on the cell surface. This finding is intriguing since infection with CHIKV is attenuated by IFNα (Couderc et al., 2008; King and Goodbourn, 1994). Upon induction by IFNα, BST-2 incorporates into HIV-1 particle (Fitzpatrick et al., 2010). Although we have not yet determined if BST-2 is incorporated into CHIKV VLPs, the fact that SEM analysis reveal that, in the presence of BST-2 and absence of nsP1, CHIKV VLPs are tethered to the cell membrane as well as to each other suggests that BST-2 may be incorporated into CHIKV VLPs.

Conclusion

The observation that BST-2 retains budding CHIKV VLPs on the host plasma membrane suggests that BST-2 might be an important component of the broad innate antiviral defense against CHIKV. Future work will determine whether BST-2 restricts the replication of infectious CHIKV and identify the structural requirements of nsP1-dependent antagonism of BST-2.

Experimental Procedures

Molecular constructs

BST-2 plasmids used in the study were previously described (Kaletsky et al., 2009) and kindly provided by Dr. Paul Bates, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. Yellow fluorescence protein (YFP) fused to N-terminus of BST-2 (yfpBST-2) was generated by amplifying the mouse BST-2 gene with primers containing XhoI and EcoRI restrictions sites. The amplicon was ligated into YFP-C1 vector construct (Clontech). The correct sequence was confirmed by restriction digest and automated nucleotide sequencing. Expression vector encoding CHIKV structural proteins (CHIKVsp) was previously described (Akahata et al., 2010) and kindly provided by Dr. Gary Nabel of National Institute of Allergy Infectious Diseases. mCherry tagged plasmids encoding various CHIKV proteins (nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, nsP4, E1, E2, E3, Capsid, K6) were previously described (Pellet et al., 2010) and generously provided by Dr. Pierre-Olivier Vidalain of Unité de Génomique Virale et Vaccination, Institut Pasteur, France through Dr. Deborah Lenschow of Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Cell culture

293T (human embryonic kidney) cells were from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO), 1% L-glutamine (GIBCO), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (GIBCO).

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse anti-CHIKV was obtained from the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCEVA) through Dr. Robert Tesh of the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) Galveston, Texas. AlexaFluor goat anti-mouse secondary antibody was from Life Technology while Allophycocyanin (APC) conjugated anti-BST-2 was previously described (Jones et al., 2012a). Recombinant human interferon alpha (IFNα) was obtained from R&D systems.

Transfections

293T cells were grown in 6-well cell culture plates or in cover slips depending on experiments. Cells were then transfected with FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Roche) with 1 to 3 µg of relevant plasmids, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

IFNα stimulation

293T cells were stimulated with 1000 units/ml of IFNα for 24 hours prior to transfections with relevant plasmids. Cells were prepared for FACS or scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)

FACS analysis was conducted as previously described (Okeoma et al., 2008). Briefly, approximately 5 × 105 cells were incubated with anti BST-2 or relevant IgG antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were washed in PBS + 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. In some experiments, yfp expression was evaluated in place of BST-2. At least 10,000 events were collected for each sample with FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD). Cellular frequency and mean fluorescence intensity were determined by Flowjo analysis software (TreeStar).

Microscopy

Microscopic examination of cells were carried out as previously described (Jones et al., 2012a). Briefly, cells plated on coverslips or 6-well plates were transfected with yfp or mCherry tagged plasmids expressing relevant proteins. Alternatively, cells were stimulated with IFNα or vehicle followed by transfections. Anti-mouse CHIKV polyclonal antibody and AlexaFluor goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies were used for staining when required. Cells were prepared for either confocal or SEM imaging (Jones et al., 2012a) depending on experiment. Confocal images were acquired using Zeiss 510 confocal microscope and where applicable, Z-series images were collected at 0.14 µm intervals from randomly selected cells under each condition. 3D reconstructions of images were processed using ZEN 2009 light edition (Zeiss). SEM images were obtained with Hitachi S4800 scanning electron microscope.

Fluorescent mean intensity computation

Z stacks from confocal fluorescence microscopy of transfected cells were obtained using Zen 2009 Light Edition (Zeiss). For each z stack, the mean intensity ± standard deviation per fluorescence (yfp-BST-2, mCherry-CHIKV nsP1 and E1) was obtained using imaris imaging software.

VLPs quantification

TEM images of individual cells magnified five thousand fold were subjected to semiquantitative analysis of non-overlapping CHIKV VLPs tethered to the surface of 293T cells. VLPs from four fields per test condition were counted. Mean tethered CHIKV VLPs numbers reported are simple averages of VLPs counted from four fields per sample. Total CHIKV VLPs counted for CHIKVsp alone, CHIKVsp + BST-2, CHIKVsp + BST-2 + E1, and CHIKVsp + BST-2 + nsP1 were 1170, 3553, 2743, and 187 respectively. At least 187 counts were used to prepare the histogram. The number of CHIKV VLPs could not be normalized between test conditions because in the presence of nsp1 very few VLPs are retained on the cell surface (187 VLPs versus 3553 VLPs in the absence of nsp1). Therefore the Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 and groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer posttest for analysis of unequal sample sizes.

RNA-Immunoprecipitation

RNA-IP with BST-2 and CHIKV were performed on 293T cells transfected with mouse yfpBST-2 only, CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2, CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 + CHIKV E1, and CHIKVsp + yfpBST-2 + CHIKV nsP1 for 24 h in 24-well plates (3 ug total plasmid) at a density of 1 × 106 cells. After incubation, supernatant was collected, filtered and stored. Cells were washed with 1 × PBS, harvested by trypsinization, and then resuspended in buffer containing 2 parts 1 × PBS, 2 parts nuclear isolation buffer (1.28 M sucrose, 40 mM TRIS-HCL ph 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 4% Triton X-1-00), 6 parts dH2O. Nuclear lysates were kept on ice for 20 min with constant mixing with the cell nuclei pelleted by centrifugation at 2500g for 15 min. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 1 ml RIP buffer (150 mM KCl, 25 mM TRIS ph 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5% NP40, 100 U/ml RNaseOUT™ (Invitrogen) Recombinant Ribonuclease Inhibitior). Resuspended nuclei were split into four equal amounts (one for Inputs, three for RNA IP) then mechanically sheared using a pestle to break up the chromatin. The nuclear pellet and cell debris were pelleted again by centrifugation at 13000 rpm for 10 min. Fresh RIP buffer was added (300 ul) to each fractions designated for RNA IP, the inputs were resuspended in 50 ul PBS and stored for RNA extraction. Each RNA IP fraction per transfection received 1 ul of antibody (anti-mouse CHIKV, anti-rabbit BST-2 (mouse), anti-rabbit YFP), then incubated overnight with light rotation at 4°C. Next, 40 ul of Protein A agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to each fraction then rotated for 1 hr at 4°C. The RNA IP fractions were then pelleted at 2500 rpm for 30 s in which the supernatant removed by vacuum and the beads were resuspended in 500 ul RIP. A total of three RIP washings and one PBS washing with the isolated beads along with the input pellets resuspended in 1 ml of TRlzol for RNA extraction (following manufacturer’s instructions). RNA was eluted in 25 ul nuclease-free water, their concentrations standardize, and a total of 20 ul cDNA was prepared (Applied Biosciences). The cDNA was diluted to 50 ng/ul in which PCR was then conducted using 21 ul GoTaq® Hot Start Green Master Mix (Promega), 2 ul forward/reverse primer mixture (RNA IP – CHIKV: Primer used – mouse BST-2; RNA IP – mouse BST-2 and RNA IP – YFP: Primers used – CHIKV nsP1 and CHIKV E1), 2 ul cDNA (100 ug). PCR was performed on Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems) at 2 min at 95°C, then 35 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, 1 min at 72°C, then 5 min at 72°C. PCR product was loaded onto a 1.5% agarose gel and then gel electrophoresis conducted at 90 V for 45 minutes.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 and groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer posttest for analysis of unequal sample sizes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Paul Bates, Gary Nabel, Deborah Lenschow, and Pierre-Olivier Vidalain for kindly providing us with different reagents. Our appreciation goes to Bryson Okeoma for important editorial input. This work was supported by departmental support to CMO and PHJ was supported by Immunology T32 training grant to the University of Iowa. This research was made possible through core services provided by the University of Iowa Central Microscopy.

List of abbreviations

- BST-2

bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2

- CHIKV

Chikungunya virus

- VLP

Virus like particle

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- MLV

Murine leukemia virus

- MMTV

mouse mammary tumor virus

- IFNα

interferon alpha

- SEM

scanning electron micrograph

- nsPs

nonstructural proteins

- E1

envelope glycoprotein 1

- yfp

yellow fluorescent protein.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Authors’ contributions: PHJ and CMO conceptualized and designed research, PHJ, MM, and MNM performed research and analyzed data; PHJ, MM, RJR, WM, CMO wrote and read the paper. RJR and WM contributed reagents. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Authors’ information: PHJ, MM, MNM, WM, RJR, CMO - Department of Microbiology, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

MM - School of Biological Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639798

References

- Ahola T, Kaariainen L. Reaction in alphavirus mRNA capping: formation of a covalent complex of nonstructural protein nsP1 with 7-methyl-GMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahola T, Kujala P, Tuittila M, Blom T, Laakkonen P, Hinkkanen A, Auvinen P. Effects of palmitoylation of replicase protein nsP1 on alphavirus infection. J Virol. 2000;74:6725–6733. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6725-6733.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akahata W, Yang ZY, Andersen H, Sun S, Holdaway HA, Kong WP, Lewis MG, Higgs S, Rossmann MG, Rao S, Nabel GJ. A virus-like particle vaccine for epidemic Chikungunya virus protects nonhuman primates against infection. Nat Med. 2010;16:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nm.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartee E, McCormack A, Fruh K. Quantitative membrane proteomics reveals new cellular targets of viral immune modulators. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop KN, Holmes RK, Sheehy AM, Davidson NO, Cho SJ, Malim MH. Cytidine deamination of retroviral DNA by diverse APOBEC proteins. Current biology : CB. 2004;14:1392–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho B, Jeon BY, Kim J, Noh J, Kim J, Park M, Park S. Expression and evaluation of Chikungunya virus E1 and E2 envelope proteins for serodiagnosis of Chikungunya virus infection. Yonsei medical journal. 2008;49:828–835. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.5.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couderc T, Chretien F, Schilte C, Disson O, Brigitte M, Guivel-Benhassine F, Touret Y, Barau G, Cayet N, Schuffenecker I, Despres P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Michault A, Albert ML, Lecuit M. A mouse model for Chikungunya: young age and inefficient type-I interferon signaling are risk factors for severe disease. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube M, Bego MG, Paquay C, Cohen EA. Modulation of HIV-1-host interaction: role of the Vpu accessory protein. Retrovirology. 2010a;7:114. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube M, Roy BB, Guiot-Guillain P, Binette J, Mercier J, Chiasson A, Cohen EA. Antagonism of tetherin restriction of HIV-1 release by Vpu involves binding and sequestration of the restriction factor in a perinuclear compartment. PLoS Pathog. 2010b;6:e1000856. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick K, Skasko M, Deerinck TJ, Crum J, Ellisman MH, Guatelli J. Direct restriction of virus release and incorporation of the interferon-induced protein BST-2 into HIV-1 particles. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1000701. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fros JJ, Liu WJ, Prow NA, Geertsema C, Ligtenberg M, Vanlandingham DL, Schnettler E, Vlak JM, Suhrbier A, Khromykh AA, Pijlman GP. Chikungunya virus nonstructural protein 2 inhibits type I/II interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling. J Virol. 2010;84:10877–10887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00949-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardin P, Barau G, Michault A, Bintner M, Randrianaivo H, Choker G, Lenglet Y, Touret Y, Bouveret A, Grivard P, Le Roux K, Blanc S, Schuffenecker I, Couderc T, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Lecuit M, Robillard PY. Multidisciplinary prospective study of mother-to-child chikungunya virus infections on the island of La Reunion. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet C, Schmidt S, Kern C, Oberbremer L, Keppler OT. Endogenous CD317/Tetherin limits replication of HIV-1 and murine leukemia virus in rodent cells and is resistant to antagonists from primate viruses. J Virol. 2010;84:11374–11384. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01067-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goila-Gaur R, Khan MA, Miyagi E, Kao S, Strebel K. Targeting APOBEC3A to the viral nucleoprotein complex confers antiviral activity. Retrovirology. 2007;4:61. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez de Cedron M, Ehsani N, Mikkola ML, Garcia JA, Kaariainen L. RNA helicase activity of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein NSP2. FEBS letters. 1999;448:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn YS, Grakoui A, Rice CM, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. Mapping of RNA-temperature-sensitive mutants of Sindbis virus: complementation group F mutants have lesions in nsP4. J Virol. 1989a;63:1194–1202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1194-1202.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn YS, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. Mapping of RNA-temperature-sensitive mutants of Sindbis virus: assignment of complementation groups A, B, and G to nonstructural proteins. J Virol. 1989b;63:3142–3150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3142-3150.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds J, Wang JJ, Yi H, Spearman P. Immunoelectron microscopic evidence for Tetherin/BST2 as the physical bridge between HIV-1 virions and the plasma membrane. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000749. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy WR, Strauss JH. Processing the nonstructural polyproteins of sindbis virus: nonstructural proteinase is in the C-terminal half of nsP2 and functions both in cis and in trans. J Virol. 1989;63:4653–4664. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4653-4664.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser H, Lopez LA, Yang SJ, Oldenburg JE, Exline CM, Guatelli JC, Cannon PM. HIV-1 Vpu and HIV-2 Env counteract BST-2/tetherin by sequestration in a perinuclear compartment. Retrovirology. 2010;7:51. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Her Z, Malleret B, Chan M, Ong EK, Wong SC, Kwek DJ, Tolou H, Lin RT, Tambyah PA, Renia L, Ng LF. Active infection of human blood monocytes by Chikungunya virus triggers an innate immune response. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2010;184:5903–5913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly C, Booth NJ, Neil SJ. Cell-cell spread of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 overcomes tetherin/BST-2-mediated restriction in T cells. J Virol. 2010;84:12185–12199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01447-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Mehta HV, Maric M, Roller RJ, Okeoma CM. Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 (BST-2) restricts mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) replication in vivo. Retrovirology. 2012a;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PH, Mehta HV, Okeoma CM. A novel role for APOBEC3: Susceptibility to sexual transmission of murine acquired immunodeficiency virus (mAIDS) is aggravated in APOBEC3 deficient mice. Retrovirology. 2012b;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaletsky RL, Francica JR, Agrawal-Gamse C, Bates P. Tetherin-mediated restriction of filovirus budding is antagonized by the Ebola glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2886–2891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811014106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiiver K, Tagen I, Zusinaite E, Tamberg N, Fazakerley JK, Merits A. Properties of non-structural protein 1 of Semliki Forest virus and its interference with virus replication. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1457–1466. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/000299-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P, Goodbourn S. The beta-interferon promoter responds to priming through multiple independent regulatory elements. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30609–30615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakkonen P, Ahola T, Kaariainen L. The effects of palmitoylation on membrane association of Semliki forest virus RNA capping enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28567–28571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.45.28567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laakkonen P, Auvinen P, Kujala P, Kaariainen L. Alphavirus replicase protein NSP1 induces filopodia and rearrangement of actin filaments. J Virol. 1998;72:10265–10269. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10265-10269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahariya C, Pradhan SK. Emergence of chikungunya virus in Indian subcontinent after 32 years: A review. Journal of vector borne diseases. 2006;43:151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam S, Chen KC, Ng MM, Chu JJ. Expression of Plasmid-Based shRNA against the E1 and nsP1 Genes Effectively Silenced Chikungunya Virus Replication. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Tortorec A, Willey S, Neil SJ. Antiviral inhibition of enveloped virus release by tetherin/BST-2: action and counteraction. Viruses. 2011;3:520–540. doi: 10.3390/v3050520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JY, Ng MM, Chu JJ. Replication of alphaviruses: a review on the entry process of alphaviruses into cells. Advances in virology. 2011;2011:249640. doi: 10.1155/2011/249640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez LA, Yang SJ, Hauser H, Exline CM, Haworth KG, Oldenburg J, Cannon PM. Ebola virus glycoprotein counteracts BST-2/Tetherin restriction in a sequence-independent manner that does not require tetherin surface removal. J Virol. 2010;84:7243–7255. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02636-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low A, Okeoma CM, Lovsin N, de las Heras M, Taylor TH, Peterlin BM, Ross SR, Fan H. Enhanced replication and pathogenesis of Moloney murine leukemia virus in mice defective in the murine APOBEC3 gene. Virology. 2009;385:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden WH. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. II. General description and epidemiology. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:33–57. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malet H, Coutard B, Jamal S, Dutartre H, Papageorgiou N, Neuvonen M, Ahola T, Forrester N, Gould EA, Lafitte D, Ferron F, Lescar J, Gorbalenya AE, de Lamballerie X, Canard B. The crystal structures of Chikungunya and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus nsP3 macro domains define a conserved adenosine binding pocket. J Virol. 2009;83:6534–6545. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00189-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeat B, Cavagliotti L, Lehmann M, Gers-Huber G, Kaur I, Thomas Y, Kaiser L, Piguet V. Influenza Virus Partially Counteracts Restriction Imposed by Tetherin/BST-2. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22015–22029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.319996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangeat B, Gers-Huber G, Lehmann M, Zufferey M, Luban J, Piguet V. HIV-1 Vpu neutralizes the antiviral factor Tetherin/BST-2 by binding it and directing its beta-TrCP2-dependent degradation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000574. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta HV, Jones PH, Weiss JP, Okeoma CM. IFN-alpha and Lipopolysaccharide Upregulate APOBEC3 mRNA through Different Signaling Pathways. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 2012;189:4088–4103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Durbin R, Huang HV, Rice CM, Stollar V. Association of the Sindbis virus RNA methyltransferase activity with the nonstructural protein nsP1. Virology. 1989;170:385–391. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison TE, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Whitmore AC, Lotstein AR, Gunn BM, Elmore SA, Heise MT. A mouse model of chikungunya virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease: evidence of arthritis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and persistence. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil S, Bieniasz P. Human immunodeficiency virus, restriction factors, and interferon. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:569–580. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neil SJ, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature. 2008;451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeoma CM, Huegel AL, Lingappa J, Feldman MD, Ross SR. APOBEC3 proteins expressed in mammary epithelial cells are packaged into retroviruses and can restrict transmission of milk-borne virions. Cell host & microbe. 2010;8:534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeoma CM, Lovsin N, Peterlin BM, Ross SR. APOBEC3 inhibits mouse mammary tumour virus replication in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:927–930. doi: 10.1038/nature05540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeoma CM, Low A, Bailis W, Fan HY, Peterlin BM, Ross SR. Induction of APOBEC3 in vivo causes increased restriction of retrovirus infection. Journal of virology. 2009a;83:3486–3495. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02347-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeoma CM, Petersen J, Ross SR. Expression of murine APOBEC3 alleles in different mouse strains and their effect on mouse mammary tumor virus infection. Journal of virology. 2009b;83:3029–3038. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeoma CM, Shen M, Ross SR. A novel block to mouse mammary tumor virus infection of lymphocytes in B10.BR mice. Journal of virology. 2008;82:1314–1322. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01848-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Griffin DE. The nsP3 macro domain is important for Sindbis virus replication in neurons and neurovirulence in mice. Virology. 2009;388:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease LF, 3rd, Lipin DI, Tsai DH, Zachariah MR, Lua LH, Tarlov MJ, Middelberg AP. Quantitative characterization of virus-like particles by asymmetrical flow field flow fractionation, electrospray differential mobility analysis, and transmission electron microscopy. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2009;102:845–855. doi: 10.1002/bit.22085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellet J, Tafforeau L, Lucas-Hourani M, Navratil V, Meyniel L, Achaz G, Guironnet-Paquet A, Aublin-Gex A, Caignard G, Cassonnet P, Chaboud A, Chantier T, Deloire A, Demeret C, Le Breton M, Neveu G, Jacotot L, Vaglio P, Delmotte S, Gautier C, Combet C, Deleage G, Favre M, Tangy F, Jacob Y, Andre P, Lotteau V, Rabourdin-Combe C, Vidalain PO. ViralORFeome: an integrated database to generate a versatile collection of viral ORFs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D371–D378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peranen J, Laakkonen P, Hyvonen M, Kaariainen L. The alphavirus replicase protein nsP1 is membrane-associated and has affinity to endocytic organelles. Virology. 1995;208:610–620. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollason R, Korolchuk V, Hamilton C, Jepson M, Banting G. A CD317/tetherin-RICH2 complex plays a critical role in the organization of the subapical actin cytoskeleton in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:721–736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Lau D, Mitchell RS, Hill MS, Schmitt K, Guatelli JC, Stephens EB. BST-2 mediated restriction of simian-human immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 2010;406:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A, Vasiljeva L, Merits A, Magden J, Jokitalo E, Kaariainen L. Properly folded nonstructural polyprotein directs the semliki forest virus replication complex to the endosomal compartment. J Virol. 2003;77:1691–1702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.1691-1702.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilte C, Couderc T, Chretien F, Sourisseau M, Gangneux N, Guivel-Benhassine F, Kraxner A, Tschopp J, Higgs S, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Colonna M, Peduto L, Schwartz O, Lecuit M, Albert ML. Type I IFN controls chikungunya virus via its action on nonhematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:429–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuffenecker I, Iteman I, Michault A, Murri S, Frangeul L, Vaney MC, Lavenir R, Pardigon N, Reynes JM, Pettinelli F, Biscornet L, Diancourt L, Michel S, Duquerroy S, Guigon G, Frenkiel MP, Brehin AC, Cubito N, Despres P, Kunst F, Rey FA, Zeller H, Brisse S. Genome microevolution of chikungunya viruses causing the Indian Ocean outbreak. PLoS medicine. 2006;3:e263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirako Y, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. Suppressor mutations that allow sindbis virus RNA polymerase to function with nonaromatic amino acids at the N-terminus: evidence for interaction between nsP1 and nsP4 in minus-strand RNA synthesis. Virology. 2000;276:148–160. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirako Y, Strauss JH. Regulation of Sindbis virus RNA replication: uncleaved P123 and nsP4 function in minus-strand RNA synthesis, whereas cleaved products from P123 are required for efficient plus-strand RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1994;68:1874–1885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1874-1885.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solignat M, Gay B, Higgs S, Briant L, Devaux C. Replication cycle of chikungunya: a re-emerging arbovirus. Virology. 2009;393:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suspene R, Guetard D, Henry M, Sommer P, Wain-Hobson S, Vartanian JP. Extensive editing of both hepatitis B virus DNA strands by APOBEC3 cytidine deaminases in vitro and in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:8321–8326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408223102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuittila M, Hinkkanen AE. Amino acid mutations in the replicase protein nsP3 of Semliki Forest virus cumulatively affect neurovirulence. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1525–1533. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18936-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme N, Goff D, Katsura C, Jorgenson RL, Mitchell R, Johnson MC, Stephens EB, Guatelli J. The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiljeva L, Merits A, Auvinen P, Kaariainen L. Identification of a novel function of the alphavirus capping apparatus. RNA 5'-triphosphatase activity of Nsp2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17281–17287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910340199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss JE, Vaney MC, Duquerroy S, Vonrhein C, Girard-Blanc C, Crublet E, Thompson A, Bricogne G, Rey FA. Glycoprotein organization of Chikungunya virus particles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 2010;468:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werneke SW, Schilte C, Rohatgi A, Monte KJ, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Vanlandingham DL, Higgs S, Fontanet A, Albert ML, Lenschow DJ. ISG15 is critical in the control of Chikungunya virus infection independent of UbE1L mediated conjugation. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002322. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Chen D, Konig R, Mariani R, Unutmaz D, Landau NR. APOBEC3B and APOBEC3C are potent inhibitors of simian immunodeficiency virus replication. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:53379–53386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Liang C. BST-2 diminishes HIV-1 infectivity. J Virol. 2010;84:12336–12343. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01228-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]