Abstract

Noonan Syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by short stature, congenital heart defects, developmental delay, dysmorphic facial features and occasional lymphatic dysplasias. The features of Noonan Syndrome change with age and have variable expression. The diagnosis has historically been based on clinical grounds. We describe a child that was born with congenital refractory chylothorax and subcutaneous edema suspected to be secondary to pulmonary lymphangiectasis. The infant died of respiratory failure and anasarca at 80 days. The autopsy confirmed lymphatic dysplasia in lungs and mesentery. The baby had no dysmorphic facial features and was diagnosed postmortem with Noonan syndrome by genomic DNA sequence analysis as he had a heterozygous mutation for G503R in the PTPN11 gene.

Keywords: chylothorax, genomic DNA sequence, lymphatic dysplasia, Noonan syndrome, pulmonary lymphangiectasis

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Jacqueline A. Noonan originally defined Noonan Syndrome in 1963 in a study of nine children. There were six boys and three girls that had a rare type of heart defect, valvular pulmonary stenosis and characteristics of their physical appearance included short stature, webbed neck, wide-spaced eyes, low-set posteriorly rotated ears and chest deformities [1]. The first reported case of this syndrome was actually in 1883 by Kobylinski who reported a 20-year-old patient with a webbed neck [2]. Dr. John Opitz, a student of Dr. Noonan, first began calling it Noonan Syndrome.

Noonan Syndrome (NS) is an autosomal dominant disorder with great variability in expression of its characteristic features. Several scoring systems have been devised to help in the diagnostic process. The features of Noonan Syndrome change with age, as they are more prominent in infants and are less striking as they enter into early childhood [3]. The diagnosis of Noonan Syndrome has typically been clinically identified, but due to the variability of expression in the syndrome, it has sometimes become difficult at an early age. Currently, patients can be tested for mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, KRAS, NRAS, RAF1, BRAF, SHOC2, MEK1 or CBL genes to help in the diagnosis [4]. However, the absence of a mutation does not exclude the diagnosis, and new undiscovered mutations may also cause Noonan Syndrome.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a dichorionic twin male that was born at 33 weeks gestation by vaginal delivery to a 26-year-old G5P4 mother after an abrupt onset of premature labor and rupture of membranes. The co-twin was a female that was delivered by a cesarean section due to a breech presentation and had no problems after delivery. Neither of the neonates had dysmorphic features nor was there any history of any genetic abnormalities in the family. Our patient developed subcostal retractions shortly after birth and was admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and given nasal continuous positive airway pressure. The chest X-ray revealed a small right-sided pleural effusion that resolved spontaneously over the following days. Initial echocardiogram showed a small ventricular septal defect, left ventricular hypertrophy, systolic anterior motion of mitral valve with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and dysplastic aortic/pulmonary valves without stenosis.

At about 2 weeks of age, the neonate again developed respiratory distress and was transferred to our tertiary care NICU to better manage his respiratory failure and to rule out infectious causes. He remained on various modes of mechanical ventilation throughout his NICU hospitalization. Right-sided pleural effusion reappeared on chest X-ray at six weeks of age and progressively worsened. It needed to be drained by thoracentesis, then by chest tube thoracotomy and later by pleurodesis. The clinical diagnosis of chylothorax was made based on the pleural fluid having elevated lymphocyte count, protein and LDH levels. A positive culture for Streptococcus viridans was found in the lymphocyte-rich, milky, pleural fluid and treated with systemic antibiotics. Repeat echocardiograms showed worsening biventricular hypertrophy. He developed anasarca, hypoproteinemia, severe lymphopenia, systemic hypotension and pulmonary hypertension, which subsequently led to his death at 80 days of life despite aggressive medical and surgical management. The clinical underlying cause of death consisted of massive chylothorax, pulmonary lymphangiectasia and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

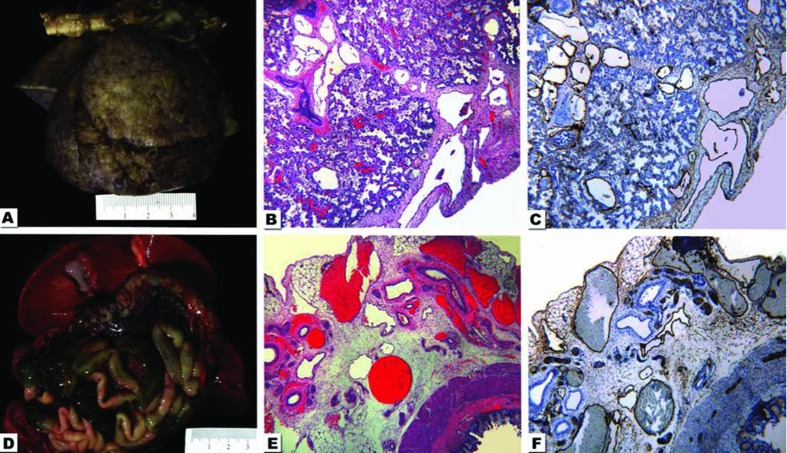

Postmortem examination of the infant disclosed severe anasarca with marked subcutaneous fluid accumulation. The lungs had an edematous, bumpy, clear appearance (Figure 1A). Histologically they demonstrated dilation of the lymphatics. They were dilated throughout the entire pleural surface of both lungs, as well as around the pulmonary septa within the lung parenchyma (Figure 1B). A D2-40 immunohistochemistry stain identified the lymphatics supporting the diagnosis of pulmonary lymphangiectasis and a cause for the refractory to treatment pleural effusion (Figure 1C). The lymphatic vessels within the mesentery were prominently identifiable and dilated (Figure 1D). A D2-40 immunohistochemistry also confirmed these mesenteric vessels as lymphatics; therefore, the baby also had intestinal lymphangiectasis (Figure 1E & F).

Figure 1. .

Composite photograph with gross and photomicrographs from the autopsy. A. The lungs after 24 h of formalin fixation. When fresh, they were pale pink with a slightly bumpy pleural surface. The aorta is horizontally placed at the upper portion of the photograph. B. Hematoxylin-and eosin (H&E)-stained photograph taken from the lung with the 4× -lens depicts the pleural surface and part of the pulmonary parenchyma. Notice the dilated vessels. C. Same field of view and magnification as in 1-B, but stained by immunohistochemistry for D2-40 highlights the lymphatic origin of dilated vessels. D. The upper part of the abdominal organs demonstrates the liver with gallbladder, intestine and congested mesenteric vessels. E. The H&E-stained photomicrograph from intestine and mesentery with the 4× -lens shows the intestine in the right lower corner and numerous dilated mesenteric vessels. F. Same field of view and magnification as in 1-E, but stained by immunohistochemistry for D2-40 highlights the lymphatic nature of dilated vessels.

Congenital lymphangiectasis possibly results from a failure of pulmonary interstitial connective tissues to regress (this normally occurs in the fifth month of fetal life) leading to dilation of pulmonary lymphatic capillaries [5]. That developmental disorder interferes with the function of the lymphatic system and eventually causes effusion of chylous fluid or lymph into either the pleural or peritoneal cavity. The presence of lymphedema, intestinal lymphangiectasis and chylothorax associated with pulmonary lymphangiectasis is a congenital developmental disorder called generalized lymphatic dysplasia [6]. This entity resulted in protein-losing enteropathy, electrolyte imbalance and severe respiratory distress, which led to our patient’s demise [7]. The cause of death of the patient was generalized lymphatic dysplasia. Due to the current recommendations on patients with pleural effusions, edema and a normal karyotype, a genetic workup for Noonan Syndrome was sent to Gene Dx. It revealed a heterozygous mutation for the G503R in the PTPN11 gene consistent with the diagnosis of Noonan syndrome (p.Gly503Arg (GGG>CGG): c.1507 G>C in exon 13 of the PTPN11 gene (NM_002834.3).

DISCUSSION

Noonan syndrome has an incidence of 1 case per 1000–2500 live births. It is seen in people of all ethnic and racial backgrounds [8]. Males and females are equally affected. The early term “male Turner syndrome” incorrectly implied that females could not have Noonan syndrome. Turner syndrome consists of an abnormality of the sex chromosome with more renal anomalies, left-sided heart defects and less developmental delay compared to the abnormalities seen in Noonan syndrome. The cardinal features of NS are short stature, congenital heart defect (dysplastic/stenotic pulmonic valve, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and septal defects are most common), developmental delay, webbed neck, scoliosis, pectus carinatum or excavatum, low-set nipples and cryptorchidism in males. The facial features in neonates consists of a broad and high forehead, hypertelorism, epicanthal folds, low-set posteriorly rotated ears, micrognathia, short neck and low posterior hairline. As the child grows, some of the features might change, such as the triangular-shaped face, down-slanting eyes, strabismus, amblyopia, refractive vision errors and high nasal bridge. In about 80% of the patients, their height is significantly below the average height of their peers. The average height of an adult male with NS is 5 foot 5 inches and 5 foot in females [9]. Other less common features seen are pyeloureteric stenosis, coagulation disorders, leukemias, lymphatic dysplasias, pigmented nevi, hearing loss and hepatosplenomegaly. There have been diagnostic criteria developed by van der Burgt to help in the investigation and management of patients with Noonan syndrome. She describes six major criteria: typical face dysmorphology, pulmonary valve stenosis/hypertrophic cardiomyopathy/typical ECG, percentile of height according to age <P3, pectus carinatum/excavatum, first-degree relative with definitive NS and mental retardation/cryptorchidism/lymphatic dysplasia. The minor criteria consist of suggestive facial dysmorphology, another cardiac defect not previously described, percentile of height according to age < P10, broad thorax, first-degree relative with suggestive NS and one of either mental retardation, cryptorchidism and/or lymphatic dysplasia [3].

In our patient, who was less than 3 months of age, certain characteristic features such as short stature and developmental delay could not be assessed. He did not have any dysmorphic features, chest deformities, relatives with NS or cryptorchidism. The three features that our baby did display were short neck (no webbed), dysplastic pulmonary valve without stenosis and lymphatic dysplasia (pulmonary and intestinal lymphangiectasis). It has been suggested that NS should be considered in all fetuses with polyhydramnios, pleural effusions, edema and increased nuchal fluid with a normal karyotype [10]. For this reason, DNA sequencing analysis was performed. There are a group of distinct syndromes with partially overlapping phenotypes in which causative mutations are found in genes of the RAS-MAPK signal transduction pathway, which include Noonan, LEOPARD, Cardio-facio-cutaneous (CFC) and Costello syndromes. A panel that evaluates BRAF, CBL, HRAS, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, NRAS, PTPN11, RAF1, SHOC2 and SOS1 genes was performed to help identify a possible mutation and a PTPN11 mutation was reported.

The PTPN11 gene is on chromosome 12q24.1. It encodes SHP-2, a cytoplasmic protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) characterized by two tandemly arranged Src homology 2 (SH2) domains at the N-terminus, a catalytic domain and a C-terminal tail containing a proline-rich region and two tyrosyl residues that undergo reversible phosphorylation [11]. SHP-2 is a critical component of signal transduction for several growth factor-, hormone-, and cytokine-signaling pathways controlling developmental processes [12] and hematopoiesis [13] as well as energy balance and metabolism [14]. Individuals with LEOPARD syndrome (lentigines, ECG conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonic stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth and sensorineural deafness) may have distinct mutations in PTPN11 that lead to a diminished catalytic activity of these SHP-2 mutants. Costello syndrome (short stature, development and intellectual disability, redundant skin of neck, hands and feet, unusually flexible joints, distinctive facial features, cardiac problems and perioral or perinasal papillomas) is caused by mutations in HRAS. CFC syndrome (cardiac abnormalities, high forehead, short nose, hypertelorism, down slanting palpebral fissures, ptosis, low-set ears, dry skin with nevi and keratosis pilaris) is by mutations in BRAF, KRAS and MEK1/2 [15]. The missense mutation in the PTPN11 gene is seen in 50% of Noonan syndrome cases, while SOS1 in 13%, RAF1 in 3–17% and KRAS in fewer than 5%. Within the cases of NS, 59% of them are familial cases, while 37% are sporadic [8]. Molecular genetic testing can confirm diagnosis in approximately 70% of cases [16].

CONCLUSION

Noonan syndrome is a genetic disorder that is passed down in an autosomal dominant pattern. With no family history, and an atypical or incomplete phenotype, the clinical diagnosing of this syndrome can be very difficult. Criteria and recommendations have been developed to detect and eventually treat this disorder. Because of these recommendations and criteria, we were able to diagnose our patient with Noonan syndrome, but unfortunately the results became available after his demise. Nowadays, with the availability of improved genetic testing, it is possible to make a more precise diagnosis in cases with incomplete morphologic features. The implication of genetic testing for syndromes is very high, not only for early and adequate treatment, but also for genetic counseling.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- [1].Noonan JA. Noonan syndrome a historical perspective. Heart Views. 2002;3:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kobylinski O. Ueber eine flughoutahnibiche ausbreitung. Am Hals Arch Anthoropol. 1883;14:342–348. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ineke van der Burgt Noonan syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tartaglia M, Gelb BD, Zenker M. Noonan syndrome and clinically related disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(1):161–179. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moore KL, Persaud TVN. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Smeltzer DM, Stickler GB, Fleming RE. Primary lymphatic dysplasia in children: chylothorax, chylous ascites, and generalized lymphatic dysplasia. Eur J Pediatr. 1986;145(4):286–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00439402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Strober W, Wochner RD, Carbone PP, Waldmann TA. Intestinal lymphangiectasia: a protein-losing enteropathy with hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphocytopenia and impaired homograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1967;46(10):1643–1656. doi: 10.1172/JCI105656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Allanson JE. Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet. 1987;18(24):9–13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.24.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dahlgren J. GH therapy in Noonan syndrome: Review of final height data. Horm Res. 2009;72(Suppl. 2):46–48. doi: 10.1159/000243779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Croonen EA, Nillesen WM, Stuurman KE, et al. Prenatal diagnostic testing of the Noonan syndrome genes in fetuses with abnormal ultrasound findings. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(9):936–942. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The ‘Shp’ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tang TL, Freeman RM, Jr, O’Reilly AM, et al. The SH2-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase SH-PTP2 is required upstream of MAP kinase for early Xenopus development. Cell. 1995;80:473–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90498-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Qu CK, Nguyen S, Chen J, Feng GS. Requirement of Shp-2 tyrosine phosphatase in lymphoid and hematopoietic cell development. Blood. 2001;97:911–914. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang EE, Chapeau E, Hagihara K, Feng GS. Neuronal Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase controls energy balance and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16064–16069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sarkozy A, Conti E, Seripa D, et al. Correlation between PTPN11 gene mutations and congenital heart defects in Noonan and LEOPARD syndromes. J Med Genet. 2003;40:704–708. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.9.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bhambhani V, Muenke M. Noonan Syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(1):37–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]