Abstract

Objectives

Although the Val158Met catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene has been linked with the temperament dimension Novelty Seeking (NS), new insights in this polymorphism might point to a major role for character features as well. Given that individual life experiences may influence Val158 and Met158 allele carriers differently it has been suggested that the character trait cooperativeness could be implicated.

Case report

A homogeneous group of eighty right-handed Caucasian healthy female university students were assessed with the TCI and genotyped for the COMT Val158Met polymorphism (rs4680). Gene determination showed that eighteen were Val158 homozygotes, forty-four Val/Met158 heterozygotes, and eighteen were Met158 homozygotes. All were within the same age range and never documented to have suffered from any neuropsychiatric illness. Bonferroni corrected non-parametric analyses showed that only for the character scale cooperativeness Val158 homozygotes displayed significant higher scores when compared to Met158 homozygotes. No significant differences on cooperativeness scores were found between Val158 and Val/Met158 carriers or between Met158 and Val/Met158 carriers. No differences were observed for the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and the other temperament and character scales.

Conclusions

Our findings support the assumption that the Val158Met single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) influences character traits and not only temperament. Our results add to the notion that Val158 homozygotes are considered to be helpful and empathic and it suggest that these cooperativeness character traits are related to the dopaminergic system.

Keywords: Catechol-O-methyltransferase, cooperativeness, personality

Introduction

Notwithstanding that the concept of “personality” has been thoroughly investigated, the interplay between personality features and genetics remains poorly understood. The Val158Met polymorphism of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene (rs4680), which is involved in the degradation of the dopamine neurotransmitter, has been associated with personality (disorders) and with a range of psychiatric illnesses (Hosák 2007; Calati et al. 2011; Witte and Flöel 2012). Although Val158 carriers may display more resilience (Kang et al. 2013), Met158 allele carriers have been commonly related with a higher risk for emotional dysregulation (Kempton et al. 2009). However, the current literature is not consistent on this issue. Some studies reported that the Met158 allele is associated with increased limbic responsiveness to negative stimuli (Smolka et al. 2005, 2007), whereas others reported the opposite (Kempton et al. 2009; Domschke et al. 2012) or described null results (Drabant et al. 2006). In Cloningers' influential psychobiological model of personality (Cloninger et al. 1994), the dopaminergic-related temperament dimension Novelty Seeking (NS), and to some extent the serotonergic-associated temperament Harm Avoidance (HA), have been linked with the COMT Val158Met gene; the latter, however, mostly found in Asian populations (Montag et al. 2012).

Interestingly, Baumann et al. (2013) found that early aversive life experiences might increase the vulnerability toward anxiety disorders in COMT Met158 allele carriers and Drury et al. (2010) showed that early severe social deprivation was associated with a higher risk to develop major depression disorder in Val158 homozygotes. These findings suggest that not only genetically heritability dimensions such as temperament can be modulated by the COMT Val158Met gene but also by environmental factors. Indeed, whereas “Temperament” refers to biases in automatic responses to emotional stimuli and is to some extent independently heritable, “Character” refers to individual differences in self-object relationships, which develop in a stage-like manner as a result of nonlinear interactions among temperament, family environment, and individual life experiences (Cloninger et al. 1994).

Pełka-Wysiecka et al. (2012) found that the dopamine transporter (DAT) gene was positively correlated with the character scale cooperativeness (CO: helpful and empathic vs. hostile and aggressive) in women without psychiatric disorders. Moreover, Caucasian carriers of at least one Val158 allele showed a greater effect for social facilitation and cooperativeness (working together in group) than Met158 homozygotes (Walter et al. 2011). In an experimental study testing COMT Val158Met polymorphism for altruistic behavior, Reuter et al. (2011) found that the highest correlation between the amounts of donations was observed for CO. Although the Val158 allele was related to the level of altruism, CO was not. Because no effects of gender were examined this could explain to some extent the lack of such association. Besides age also gender may confound COMT Val158Met gene results (Harrison & Tunbridge 2008), also related to personality (Chen et al. 2011).

Consequently, we hypothesized that in a homogeneous sample of Caucasian females, selected within a narrow age range, never documented to have suffered from any neuropsychiatric illness, that individual scores on the temperament dimension NS and the character scale CO would differ for COMT Val158 and Met158 allele carriers. We expected that Val158 allele carriers would display lower scores on NS and higher scores on CO. We did not expect any interaction with the other scales of Cloningers' Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI; Cloninger et al. 1994).

Material and Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the ethics committee of our University Hospital (UZBrussel) and all subjects gave written informed consent. Eighty right-handed Caucasian female participants, all university students, were recruited (mean age = 21.7 years, SD = 2.5). Right-handedness was assessed with the van Strien questionnaire (Van Strien and Van Beek 2000). None had ever used major psychotropic medications and all were free of any drug. Subjects taking medication, other than birth-control pills, were excluded. To exclude psychiatric or neurological diseases all volunteers were screened by the first author (C.B.). Psychiatric disorders were assessed by the Dutch version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al. 1998). Subjects with a psychiatric disorder and/or a score higher than 8 on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996) were excluded. All were assessed using a Dutch version of the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) (de la Rie et al. 1998).

Temperament and character inventory

The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) is a 240-item questionnaire developed by Cloninger (1987) and Cloninger et al. (1994). The TCI consists of four temperament scales [Harm Avoidance (HA), Novelty seeking (NS), Reward dependence (RD), Persistence (P)], and three character scales [Cooperativeness (CO), Self-directedness (SD), and Self Transcendence (ST)].

Genetics

In a first step, EDTA acid anti-coagulated blood samples were drawn from each participant and DNA was isolated. Second, genotyping of COMT rs4680 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was performed using the MassARRAY platform (SEQUENOM, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis

All collected data were analyzed with SPSS 22 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05, two-tailed.

The Shapiro–Wilk normality test showed that the temperament and character scale scores were not normally distributed (P's < 0.05). Log transformation or square root transformation did not result in normality. Therefore, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U test analyses were used. We used each of the seven scales of Cloningers' Temperament and Character Inventory as dependent variable in separate analyses. The independent variables in the follow-up Mann–Whitney U test were the three genotypes (Val158, Val158Met, Met158). Follow-up Mann–Whitney U tests were Bonferroni corrected for the number of significant main effects and contrasts within these main effects.

Results

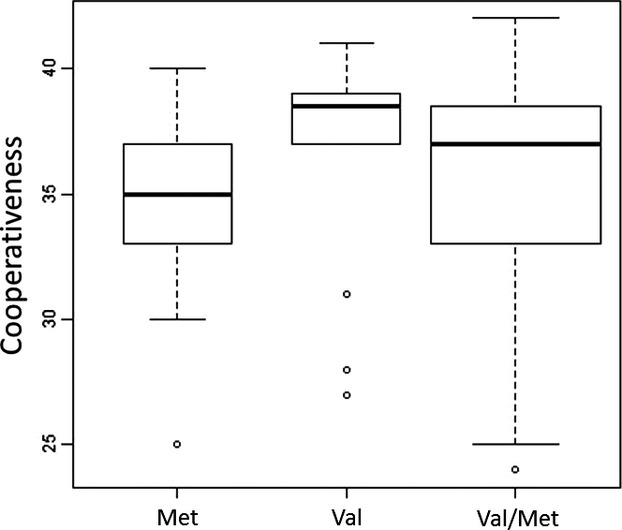

From the 80 participants, 18 were Val158 homozygotes, 44 Val/Met158 heterozygotes, and 18 were Met158 homozygotes. See also Table 1 and Figure 1. The calculation of the Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium for two alleles showed no deviation of this assumption (χ2[1, N = 80] = 0.80, P = 0.37).

Table 1.

Group variables catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met and temperament and character inventory (TCI) scores: medians and ranges

| TCI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number | Age | NS | HA | RD | P | SD | CO | ST |

| All | 80 | 21 (12) | 22 (26) | 15 (29) | 19 (15) | 4 (8) | 34 (33) | 37 (18) | 7 (27) |

| Val158 | 18 | 22.5 (11) | 22.5 (25) | 14.5 (22) | 18 (13) | 5 (8) | 34.5 (26) | 38.5 (14) | 6.5 (21) |

| Val/Met158 | 44 | 21 (10) | 22.5 (25) | 15.5 (28) | 19 (14) | 3.5 (8) | 33 (32) | 37 (18) | 7 (27) |

| Met158 | 18 | 21 (7) | 21 (21) | 14.5 (27) | 18.5 (15) | 4.5 (6) | 34.5 (26) | 35.0 (15) | 9 (17) |

Figure 1.

Boxplot representation of the COMTVal158Met gene in relation to the individual scores on cooperativeness (y-axis).

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test indicate that there is a significant difference in the medians of Val158 – Val/Met158 – Met158 allele carriers, however, this was only for the temperament scale Persistence (χ2[2, N = 80] = 6.24, P = 0.04) and the character scale Cooperativeness (χ2[2, N = 80] = 8.24, P = 0.02). All other TCI scales were not significant (P's > 0.05).

To follow-up on both significant main effects, Mann–Whitney U test revealed that for the character scale Cooperativeness Val158 homozygotes displayed significant higher CO scores when compared to Met158 homozygotes (z = −2.84, n – ties = 36, P = 0.03). No significant differences on CO scores were found between Val158 and Val/Met158 carriers (z = −1.75, n – ties = 62, P = 0.48) or between Met158 and Val/Met158 carriers (z = −1.68, n – ties = 62, P = 0.55). Mann–Whitney U test revealed no significant group differences for the temperament scale Persistence (P's > 0.05). These Mann–Whitney U tests were Bonferroni corrected for the six comparisons.

Finally, the Kruskal–Wallis test did not show differences in age between the three groups (χ2[2, N = 80] = 4.07, P = 0.13).

Discussion

In contrast to our initial hypothesis, we did not observe an influence of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism on the temperament dimension NS. Only one study observed that female Met158 carriers show higher NS scores (Golimbet et al. 2007). As to how this differs from our study is not easy to explain as the sample size was similar to ours (n = 74). One could speculate that the choice of their participants, all born in Moscow, Russia, with a wider age range and the fact that the authors used a shortened TCI version (with 125 instead of 204 items) could account for some of the discrepancies. Furthermore, other studies showing an association with NS and the COMT Val158Met gene observed such phenomena only in gene × gene interactions, by analyzing NS subscales or by cross-referencing different personality questionnaires (Salo et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2011; Montag et al. 2012). Because our a priori hypothesis was based on a relatively small sample and to avoid losing power we did not perform any of the extra analyses just mentioned. However, as hypothesized no effects on the temperament dimension HA were observed nor on any of the other TCI scales with the exception of the character scale cooperativeness.

Indeed, as predicted we found that healthy females carrying the Val158 homozygote variant scored significantly higher on CO when compared to Met158 homozygotes. These findings support the assumption that the Val158Met gene influences character traits and not only temperament. Given the higher scores on CO, our results add to the notion that Val158 homozygotes are considered to be helpful and empathic, socially tolerant, and compassionate. Indeed, the character scale cooperativeness is based on the concept of self as an integral part of humanity or society; with feelings of community, compassion, conscience, and charity (Kose 2003), in essence, these are all empathic processes. As mentioned earlier, homozygous 9/9VNTR DAT genotypes (higher dopamine levels) display the lowest scores on cooperativeness and compassion (Pełka-Wysiecka et al. 2012). Further, CC genotype carriers – associated with higher dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH) activity resulting in higher dopamine turnover to norepinephrine – manifest greater empathic ability compared to CT/TT genotypes (Gong et al. in press). Notwithstanding that for the latter, in addition to lower dopamine levels, empathy-related behaviors may also be determined by the noradrenergic system, these findings link lower dopaminergic activity to a genetic basis of prosocial behaviors (Ebstein et al. 2010). Because homozygote Val158 carriers display higher enzymatic activity resulting in less prefrontal dopamine (for the Met158 variant this is the reverse) (Heinz and Smolka 2006), our results further support the assumption that Val158 allele carriers display higher levels of social facilitation and cooperation and may have the tendency to be more altruistic than Met158 homozygotes (Reuter et al. 2011; Walter et al. 2011).

Although all our university students were free from any neuropsychiatric illness, females with only the Met158 allele variant scored significant lower on CO compared to Val158 homozygotes. Lower scores on CO have been related to more hostile and aggressive behavior (Svrakic and Cloninger 2010). Indeed, Met158 homozygotes seem to be more susceptible to emotional difficulties with higher levels of aggression (Albaugh et al. 2010), apathy (Mitaki et al. 2013) and also exhibit greater anxiety (Montag et al. 2008). Furthermore, such individuals are at higher risk to develop mental illnesses (Hosák 2007; Kocabas et al. 2010; Witte and Flöel 2012; Baumann et al. 2013). Men with this Met158 variant were found to be more at risk for depression, displayed lower motivational levels and this risk increased in combination with a problematic childhood (Åberg et al. 2011). In another study the trait-anger was found to be significantly associated with both low cooperativeness and depression (Balsamo 2013). Additionally, women with eating disorders carrying the Met158 allele variant scored lower on CO than the healthy control group (Mikołajczyk et al. 2010). Of note, in schizophrenic patients having the Met158 allele of the COMT gene confers a significantly increased risk for aggressive and violent behavior (Bhakta et al. 2012). In short, our findings support the hypothesis that healthy female homozygote carriers of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism (rs4680) are characterized differently on cooperativeness.

However, as the sample is relatively small, the interpretation of these results should be done cautiously. Although the selection of psychopathology-free female subjects within a narrow age range can be considered as a major advantage of the study, by including only healthy women within a certain age range, we cannot generalize our findings to men, older women or individuals with any form of psychiatric illness. Because we did not a priori select our participants based on their genetic COMT Val158Met profile, the three groups were unbalanced, which might have influenced our results.

In conclusion, Val158 homozygotes differed significantly in cooperativeness when compared to Met158 homozygote carriers, indicating that genetics may also play a key role in the development and expression of character features, in our case cooperativeness. A careful selection of individuals may facilitate the detection of COMT Val158Met gene influences on distinct aspects of character. Further research is needed to elucidate that more empathic high-scoring CO Val158 carriers and more hostile low CO scorers carrying the Met158 allele variant are indeed under dopaminergic regulation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Scientific Fund W. Gepts UZBrussel and supported by the Ghent University Multidisciplinary Research Partnership “The integrative neuroscience of behavioral control”.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Åberg E, Fandiño-Losada A, Sjöholm LK, Forsell Y, Lavebratt C. The functional Val158Met polymorphism in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is associated with depression and motivation in men from a Swedish population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;129:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albaugh MD, Harder VS, Althoff RR, Rettew DC, Ehli EA, Lengyel-Nelson T, et al. COMT Val158Met genotype as a risk factor for problem behaviors in youth. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsamo M. Personality and depression: evidence of a possible mediating role for anger trait in the relationship between cooperativeness and depression. Compr. Psychiatry. 2013;54:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann C, Klauke B, Weber H, Domschke K, Zwanzger P, Pauli P, et al. The interaction of early life experiences with COMT val158met affects anxiety sensitivity. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12:821–829. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory manual. 2nd ed. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bhakta SG, Zhang JP, Malhotra AK. The COMT Met158 allele and violence in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2012;140:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calati R, Porcelli S, Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Möller HJ, De Ronchi D, et al. Catechol-o-methyltransferase gene modulation on suicidal behavior and personality traits: review, meta-analysis and association study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011;45:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen C, Moyzis R, Dong Q, He Q, Zhu B, et al. Sex modulates the associations between the COMT gene and personality traits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1593–1598. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. A proposal. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): a guide to its development and use. Center for Psychobiology of Personality, Washington University: St Louis, MO; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Domschke K, Baune BT, Havlik L, Stuhrmann A, Suslow T, Kugel H, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene variation: impact on amygdala response to aversive stimuli. Neuroimage. 2012;60:2222–2229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabant EM, Hariri AR, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Munoz KE, Mattay VS, Kolachana BS, et al. Catechol O-methyltransferase val158met genotype and neural mechanisms related to affective arousal and regulation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:1396–1406. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury SS, Theall KP, Smyke AT, Keats BJ, Egger HL, Nelson CA, et al. Modification of depression by COMT val158met polymorphism in children exposed to early severe psychosocial deprivation. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebstein RP, Israel S, Chew SH, Zhong S, Knafo A. Genetics of human social behavior. Neuron. 2010;65:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golimbet VE, Alfimova MV, Gritsenko IK, Ebstein RP. Relationship between dopamine system genes and extraversion and novelty seeking. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2007;37:601–606. doi: 10.1007/s11055-007-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong P, Liu J, Li S, Zhou X. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene modulates individuals' empathic ability. Soc. Cogn. Affect Neurosci. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst122. in press. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Tunbridge EM. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): a gene contributing to sex differences in brain function, and to sexual dimorphism in the predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3037–3045. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Smolka MN. The effects of catechol O-methyltransferase genotype on brain activation elicited by affective stimuli and cognitive tasks. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;17:359–367. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2006.17.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosák L. Role of the COMT gene Val158Met polymorphism in mental disorders: a review. Eur. Psychiatry. 2007;22:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JI, Kim SJ, Song YY, Namkoong K, An SK. Genetic influence of COMT and BDNF gene polymorphisms on resilience in healthy college students. Neuropsychobiology. 2013;68:174–180. doi: 10.1159/000353257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton MJ, Haldane M, Jogia J, Christodoulou T, Powell J, Collier D, et al. The effects of gender and COMT Val158Met polymorphism on fearful facial affect recognition: a fMRI study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:371–381. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocabas NA, Faghel C, Barreto M, Kasper S, Linotte S, Mendlewicz J, et al. The impact of catechol-O-methyltransferase SNPs and haplotypes on treatment response phenotypes in major depressive disorder: a case-control association study. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;25:218–227. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328338b884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kose S. Psychobiological model of temperament and character. Yeni Symposium. 2003;41:86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mikołajczyk E, Grzywacz A, Samochowiec J. The association of catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype with the phenotype of women with eating disorders. Brain Res. 2010;1307:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitaki S, Isomura M, Maniwa K, Yamasaki M, Nagai A, Nabika T, et al. Apathy is associated with a single-nucleotide polymorphism in a dopamine-related gene. Neurosci. Lett. 2013;549:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C, Buckholtz JW, Hartmann P, Merz M, Burk C, Hennig J, et al. COMT genetic variation affects fear processing: psychophysiological evidence. Behav. Neurosci. 2008;122:901–909. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.4.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C, Jurkiewicz M, Reuter M. The role of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene in personality and related psychopathological disorders. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 2012;11:236–250. doi: 10.2174/187152712800672382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pełka-Wysiecka J, Ziętek J, Grzywacz A, Kucharska-Mazur J, Bienkowski P, Samochowiec J. Association of genetic polymorphisms with personality profile in individuals without psychiatric disorders. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;39:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter M, Frenzel C, Walter NT, Markett S, Montag C. Investigating the genetic basis of altruism: the role of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2011;6:662–668. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rie SM, Duijsens IJ, Cloninger CR. Temperament, character, and personality disorders. J. Personal Disord. 1998;12:362–372. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1998.12.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo J, Pulkki-Råback L, Hintsanen M, Lehtimäki T, Keltikangas-Järvinen L. The interaction between serotonin receptor 2A and catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms is associated with the novelty-seeking subscale impulsiveness. Psychiatr. Genet. 2010;20:273–281. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32833a212f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Schumann G, Wrase J, Grüsser SM, Flor H, Mann K, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase val158met genotype affects processing of emotional stimuli in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:836–842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1792-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Bühler M, Schumann G, Klein S, Hu XZ, Moayer M, et al. Gene-gene effects on central processing of aversive stimuli. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12:307–317. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svrakic DM, Cloninger RC. Epigenetic perspective on behavior development, personality, and personality disorders. Psychiatr. Danub. 2010;22:153–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien JW, Van Beek S. Ratings of emotion in laterally presented faces: sex and handedness effects. Brain Cogn. 2000;44:645–652. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter NT, Markett SA, Montag C, Reuter M. A genetic contribution to cooperation: dopamine-relevant genes are associated with social facilitation. Soc. Neurosci. 2011;6:289–301. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2010.527169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte AV, Flöel A. Effects of COMT polymorphisms on brain function and behavior in health and disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2012;88:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]