Abstract

Bis -aryloxadiazoles are common scaffolds in medicinal chemistry due to their wide range of biological activities. Previously, we identified a 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole that blocks mammary branching morphogenesis through activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). In addition to defects in mammary differentiation, AHR stimulation induces toxicity in many other tissues. We performed a structure activity relationship (SAR) study of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole to determine which moieties of the molecule are critical for AHR activation. We validated our results with a functional biological assay, using desmosome formation during mammary morphogenesis to indicate AHR activity. These findings will aid the design of oxadiazole derivative therapeutics with reduced off-target toxicity profiles.

Keywords: Oxadiazole, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor, Mammary gland, Branching morphogenesis, Dioxin

Small molecule libraries are widely used as a tool in chemical biology,1 both to probe biological pathways and to develop new therapeutics. However, the success of chemical library screening efforts is limited by library composition and size. One strategy to produce a large number of drug-like compounds is to use scaffolds that have previously generated biologically active chemicals.2 In particular, the oxadiazole nucleus has been used extensively as a scaffold in drug development3 due to the range of activities reported for its derivatives, including antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects.4–7

As a heteroaromatic ring, oxadiazoles can be prepared as several constitutional isomers. The 1,2,4-oxadiazole isomer has been used in numerous pharmacologic drugs, including metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptor antagonists,8 sphingosine-1-phosphate-1 receptor agonists,9 and anticancer apoptosis inducers.10 Additionally, we previously identified a derivative of this isoform as a potent compound that blocks mammary branching morphogenesis.11 In our assay, 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole 1 (referred as 1023 in our previous communication) was the lead compound identified in a chemical genetic screen for molecules that block mammary branching morphogenesis. Further analysis showed 1 had an EC50 of 1.2 ± 0.050 μM and blocked branching through activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR).

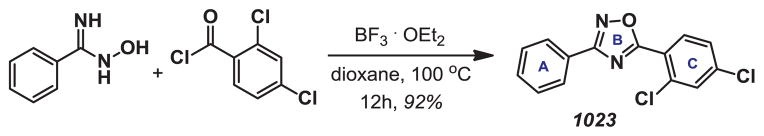

In addition to influencing mammary branching, AHR agonists also block differentiation and lactation in the mammary gland12–14 and exhibit a wide range of toxic effects in other tissues.15, 16 Our previous observations that compound 1 potently activated AHR suggested that other 1,2,4-oxadiazole derivatives may display unwanted drug effects due to AHR stimulation. Given the structural relationship of these derivatives to 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), a known carcinogen and environmental toxin that also activates AHR, we performed structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of 1 to identify key elements of the molecule that contribute to AHR activation. A library of bis-aryloxadiazoles was prepared by Lewis-acid mediated coupling of benzoyl chlorides with benzamidoximes (Scheme 1). The activity of each analog was determined by measuring expression of the AHR target gene, Cyp1a1,17, 18 in HC11 mammary epithelial cells (MECs) treated for 48 hours with 10 μM compound.

Scheme 1.

General strategy for synthesis of bis-aryloxadiazoles

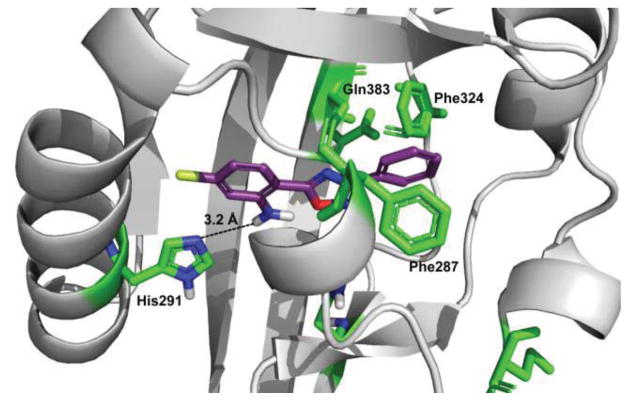

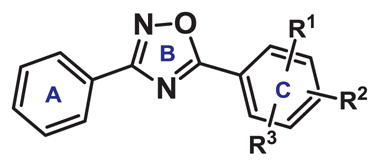

We initially made systematic modifications on the Cring of 1 (Table 1). Based on a previous homology model,11 this ring was predicted to form charge/polar interactions with amino acid residues His-291 and Gln-383 in the AHR binding pocket. Our results indicated that replacing the o-Cl substituent with an amino group (compound 2) increased AHR activity ~5-fold, as shown by increased Cyp1a1 gene expression with compound 2. In contrast, placement of an electron-withdrawing group (NO2) at the ortho position of the C-ring dramatically decreased AHR activity (compounds 3–7). These results suggested that the Cring of bis-aryloxadiazole is compatible with an electroneutral or protic-polar substitution that can be stabilized by hydrogen bonding with His-291 (Figure 1). This was confirmed by replacing the nitro group at the ortho position of compound 3 with an amino group (compound 9), which partially restored Cyp1a1 gene expression.

Table 1.

SAR study of the C-ring of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole. Expression of an AHR response gene, Cyp1a1, was measured in HC11 MECs treated with 10 μM compound for 48 hours.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R1 | R2 | R3 | Relative Cyp1a1 |

| 1 | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | 128.53 +/− 0.17 |

| 2 | o-NH2 | p-Cl | H | 638.80 +/− 0.14 |

| 3 | o-NO2 | p-CF3 | H | 0.36 +/− 0.15 |

| 4 | o-NO2 | p-OMe | H | 0.42 +/− 0.25 |

| 5 | o-NO2 | p-OH | H | 0.25 +/− 0.14 |

| 6 | o-NO2 | p-OCO2Me | H | 0.39 +/− 0.16 |

| 7 | o-NO2 | p-O-propargyl | H | 2.43 +/− 0.19 |

| 8 | o-NO2 | p-F | H | 122.64 +/− 0.12 |

| 9 | o-NH2 | p-CF3 | H | 58.63 +/− 0.15 |

| 10 | o-Cl | p-Cl | m-Cl | 25.79 +/− 0.17 |

Figure 1.

Homology model structure of human AHR (gray) and compound 2 (purple), with residues predicted to contribute to compound binding shown in green. Hydrogen bonding between the amino group at the ortho position of the C-ring and His-291 is predicted to stabilize binding.

In addition to the ortho position, the para group of the C-ring also influenced AHR activity. Specifically, p-CF3 (compound 9) showed significantly lower Cyp1a1 gene expression compared to p-Cl (compound 2). This result is likely due to the electron withdrawing and sterically bulky nature of CF3. Surprisingly, p-F (compound 8) offset the decreased activity of o-NO2 observed in other analogs. This may be explained by the small size of p-F, which would decrease van der Waals repulsion and contribute to aromatic stabilization through charge interaction. Together, modifications on the C-ring suggested bis-aryloxadiazole requires subtle electronic demand at the ortho and para positions and tight van der Waals radii at the para position to elicit significant AHR activation.

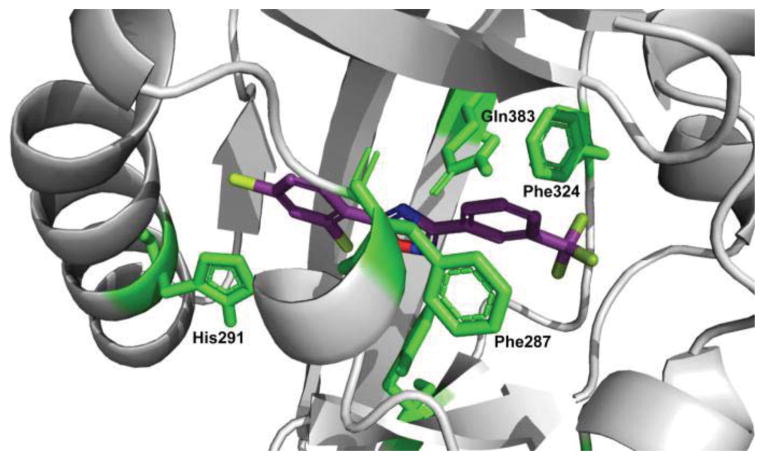

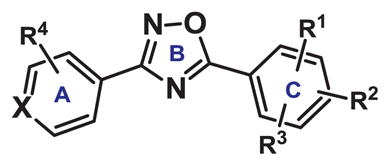

Next, we extended our SAR study to the A-ring of bis-aryloxadiazole (Table 2). Previous modeling studies11, 19 suggested this portion of the molecule binds within a tight hydrophobic cavity of AHR and is stabilized by aromatic π-stacking of Phe-324 and Phe-287. As a result, we hypothesized that functional groups on the A-ring of bis-aryloxadiazole able to distort this π-stacking would also diminish AHR activation (Figure 2). Supporting this hypothesis, we previously showed that addition of m-CF3 to the A-ring (compound 11) dramatically decreased AHR activity.11 Similarly, polar carbomethoxy or carboxylate substituents at R4 (compounds 12–14) showed low Cyp1a1 gene expression, irrespective of identities at R1 and R2. Importantly, these substitution patterns are seen in lead compounds for the treatment of nonsense mutation disorders (e.g. Ataluren).20

Table 2.

SAR study of the A-ring of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole. Expression of an AHR response gene, Cyp1a1, was measured in HC11 MECs treated with 10 μM compound for 48 hours.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | X | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Relative Cyp1a1 |

| 11 | CH | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | m-CF3 | 1.84 +/− 0.28 |

| 12 | CH | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | m-CO2Me | 0.18 +/− 0.49 |

| 13 | CH | o-F | H | H | m-CO2Me | 0.29 +/− 0.74 |

| 14 | CH | o-F | H | H | m-CO2H | 3.71 +/− 0.22 |

| 15 | CH | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | o-Cl | 5.91 +/− 0.18 |

| 16 | CH | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | m-Cl | 1.59 +/− 0.30 |

| 17 | CH | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | p-Cl | 8.15 +/− 0.14 |

| 18 | CH | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | p-O-propargyl | 0.66 +/− 0.26 |

| 19 | CH | o-NO2 | p-Cl | H | p-O-propargyl | 0.29 +/− 0.35 |

| 20 | CH | o-NH2 | p-Cl | H | p-O-allyl | 0.62 +/− 0.16 |

| 21 | CH | o-NH2 | p-Cl | H | p-O-propargyl | 0.38 +/− 0.42 |

| 22 | N | o-Cl | m-Cl | p-Cl | H | 0.53 +/− 0.28 |

| 23 | N | o-Cl | p-Cl | H | H | 0.37 +/− 0.13 |

| 24 | N | o-NO2 | p-Cl | H | H | 8.25 +/− 0.13 |

| 25 | N | o-NO2 | p-OAc | H | H | 0.35 +/− 0.41 |

Figure 2.

Homology model structure of human AHR (gray) and compound 11 (purple). Residues predicted to contribute to compound binding are shown in green. Steric interactions of the A-ring with Phe324 and Phe287 lead to decreased AHR activation.

In addition to meta substitutions, we altered other positions of the A-ring and modified the A-ring itself. Substitution of CF3 with Cl at different positions resulted in only subtle AHR activation, with p-Cl showing the highest Cyp1a1 gene induction (compound 15–17). Similarly, larger para-substituents on the A-ring (compounds 18–21) or substitution of the A-ring with a heterocycle (pyridine) nearly abolished AHR activity (compound 22–25). Taken together, these results show that any modification of the A-ring of bis-aryloxadiazole has a profound effect on AHR binding and activation.

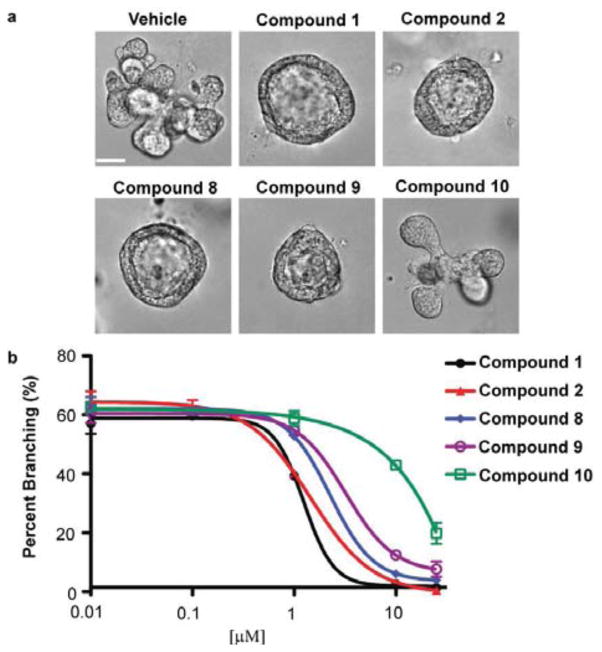

From our SAR study, we identified 4 analogs of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole that retained significant Cyp1a1 gene expression (compounds 2, 8, 9, and 10). We next validated these compounds as AHR agonists in a functional biological assay. Previously, we showed 1 potently blocked mammary branching morphogenesis of primary MECs.11 Using this same assay, we observed that compounds 2, 8, and 9 recapitulated the unbranched, cyst phenotype (Fig. 3a) and displayed an EC50 similar to compound 1 (Fig. 3b). In contrast, compound 10, which induced the lowest level of Cyp1a1 gene expression compared to the other active analogs, did not inhibit branching and displayed a relatively high EC50 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Characterization of mammary branching morphogenesis in the presence of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole analogs. (a) Representative images and (b) dose-response analysis for branching in primary MECs. Scale bar = 40 μm. Calculated EC50 values: compound 1 (1.2 +/− 0.4 μM), compound 2 (1.4 +/− 0.1 μM), compound 8 (2.2 +/− 0.1 μM), compound 9 (3.2 +/− 0.1 μM), compound 10 (>10 μM).

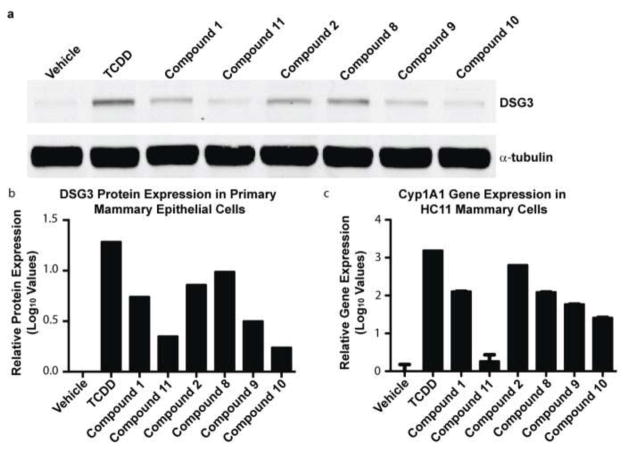

Finally, we assessed the level of desmosomal adhesion in primary MECs treated with compounds 2, 8, 9, and 10. We previously identified desmosomes as a novel target of activated AHR, which functionally disrupts mammary branching morphogenesis.11 Using desmoglein 3 (DSG3) protein levels as an indicator of desmosome complexes,21 we observed high levels of desmosomal proteins in primary MECs treated with 10 nM TCDD, which is a known AHR agonist, and 10 μM of compounds 1, 2, 8, and 9 (Fig. 4a–b). Interestingly, compounds 10 and 11 showed the lowest levels of DSG3, which correlated with their low Cyp1a1 gene expression levels and poor EC50 values in our branching assay (Fig. 4b–c). The shared patterns of Cyp1a1 gene expression and DSG3 protein levels in these biological assays suggest DSG3 is a functional indicator of AHR activity.

Figure 4.

Effect of analog compounds on desmosomal adhesion and AHR readout genes in MECs. (a) Western blot analysis and (b) quantification of desmoglein 3 (DSG3) in primary MECs. (c) Relative Cyp1a1 gene expression in HC11 MECs.

In summary, we performed SAR studies of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazole to identify components of the molecule critical for AHR activation. Our results indicated the C-ring is agonistic when substituted with electronically neutral or protic-polar moieties, particularly when tight van der Waals radii at the para position are maintained. In contrast, modification of the A-ring dramatically reduced AHR activity in all cases, suggesting this portion of the molecule significantly contributes to AHR binding and activation. These findings indicate that chemical substitutions of the A-ring that minimize AHR activation, but do not significantly alter therapeutic activity, should be considered for bis-aryloxadiazole compounds. We validated our findings by assessing the biological effects of these compounds on mammary branching morphogenesis. In agreement with our previous observations, there was a strong correlation between Cyp1a1 induction, activation of desmosomal adhesion, and a block in mammary branching morphogenesis. Since loss of desmosomes is sufficient for mammary branching,11 these results identified DSG3 as a functional readout of AHR activation. These results will aid the design and use of 1,2,4-bis-aryloxadiazoles in order to maintain biological activity of therapeutics while minimizing the activation of AHR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. David J. Bearss and Dr. Hariprasad Vankayalapati at the Center for Investigational Therapeutics, Huntsman Cancer Institute, for the modeling studies of compound 1 with human AHR. National Institutes of Health (R01-GM090082, R01-CA143815, R01-CA140296) and the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-09-1-04310) supported this work. K.J.B. is supported by National Institutes of Health Developmental Biology Training Grant 5T32 HD07491.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Mayr LM, Bojanic D. Curr Opinion Pharmacol. 2009;9:580. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welsch ME, Snyder SA, Stockwell BR. Curr Opinion Chem Biol. 2010;14:347. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bostrom J, Hogner A, Llinas A, Wellner E, Plowright AT. J Med Chem. 2012;55:1817. doi: 10.1021/jm2013248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summa V, Petrocchi A, Bonelli F, Crescenzi B, Donghi M, Ferrara M, Fiore F, Gardelli C, Gonzalez Paz O, Hazuda DJ, Jones P, Kinzel O, Laufer R, Monteagudo E, Muraglia E, Nizi E, Orvieto F, Pace P, Pescatore G, Scarpelli R, Stillmock K, Witmer MV, Rowley M. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5843. doi: 10.1021/jm800245z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pace A, Pierro P. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:4337. doi: 10.1039/b908937c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar D, Patel G, Johnson EO, Shah K. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:2739. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somani RR, Bhanushali UV. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2011;73:634. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.100237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roppe J, Smith ND, Huang D, Tehrani L, Wang B, Anderson J, Brodkin J, Chung J, Jiang X, King C, Munoz B, Varney MA, Prasit P, Cosford ND. J Med Chem. 2004;47:4645. doi: 10.1021/jm049828c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Chen W, Hale JJ, Lynch CL, Mills SG, Hajdu R, Keohane CA, Rosenbach MJ, Milligan JA, Shei GJ, Chrebet G, Parent SA, Bergstrom J, Card D, Forrest M, Quackenbush EJ, Wickham LA, Vargas H, Evans RM, Rosen H, Mandala S. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6169. doi: 10.1021/jm0503244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang HZ, Kasibhatla S, Kuemmerle J, Kemnitzer W, Ollis-Mason K, Qiu L, Crogan-Grundy C, Tseng B, Drewe J, Cai SX. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5215. doi: 10.1021/jm050292k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basham KJ, Kieffer C, Shelton DN, Leonard CJ, Bhonde VR, Vankayalapati H, Milash B, Bearss DJ, Looper RE, Welm BE. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins LL, Lew BJ, Lawrence BP. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:11. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lew BJ, Manickam R, Lawrence BP. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1094. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.087544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vorderstrasse BA, Fenton SE, Bohn AA, Cundiff JA, Lawrence BP. Toxicol Sci. 2004;78:248. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furness SG, Whelan F. Pharmacol Therap. 2009;124:336. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandal PK. J Comp Physiol B. 2005;175:221. doi: 10.1007/s00360-005-0483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tijet N, Boutros PC, Moffat ID, Okey AB, Tuomisto J, Pohjanvirta R. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:140. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitlock JP., Jr Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;39:103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motto I, Bordogna A, Soshilov AA, Denison MS, Bonati L. J Chem Inform Model. 2011;51:2868. doi: 10.1021/ci2001617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch EM, Barton ER, Zhuo J, Tomizawa Y, Friesen WJ, Trifillis P, Paushkin S, Patel M, Trotta CR, Hwang S, Wilde RG, Karp G, Takasugi J, Chen G, Jones S, Ren H, Moon YC, Corson D, Turpoff AA, Campbell JA, Conn MM, Khan A, Almstead NG, Hedrick J, Mollin A, Risher N, Weetall M, Yeh S, Branstrom AA, Colacino JM, Babiak J, Ju WD, Hirawat S, Northcutt VJ, Miller LL, Spatrick P, He F, Kawana M, Feng H, Jacobson A, Peltz SW, Sweeney HL. Nature. 2007;447:87. doi: 10.1038/nature05756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrod D, Chidgey M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.