Abstract

Physical activity plays an important role in preventing chronic disease in adults and the elderly. Exercise has beneficial effects on the nervous system, including at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Exercise causes hypertrophy of NMJs and improves recovery from peripheral nerve injuries, whereas decreased physical activity causes degenerative changes in NMJs. Recent studies have begun to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of exercise. These mechanisms involve Bassoon, neuregulin-1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α, Insulin-like growth factor-1, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin 4, Homer, and nuclear factor of activated T cells c1. For example, NMJ denervation and active zone decreases have been observed in aged NMJs, but these age-dependent degenerative changes can be ameliorated by exercise. This review will discuss the effects of exercise on the maintenance and regeneration of NMJs and will highlight recent insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying these exercise effects.

Introduction

In recent years, the importance of physical activity in preventing the development of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal, and neurological disorders, has gained increasing recognition1. The forms of exercise training that increase physical activity can be divided into endurance and resistance. The effects of these exercise types on the nervous system have been studied in humans and rodents. Endurance training is any exercise that increases the functional capacity of the aerobic system. The effects of endurance training on laboratory animals have been studied using a treadmill, running wheel, and swimming 2–5. Resistance training is any exercise that increases muscle contraction strength and anaerobic endurance. The effects of resistance training on laboratory animals have been studied using ladder climbing 6 and isometric resistance training 7–9.

Exercise is known to have beneficial effects on the nervous system, including the peripheral nervous system and NMJs 1,10. Training improves the recovery from peripheral nerve injury or degenerative changes 1,10–14. For example, increased physical activity is beneficial in recovery from the disruptive structural changes that occur in NMJs due to exposure to zero gravity during space flight 12,15. It is important to keep in mind that adult mammalian NMJs are not rigid structures. They show some degree of remodeling, including addition or reduction of presynaptic branches and postsynaptic receptors within one NMJ, and the rate of remodeling differs depending on the type of muscle 16–18. NMJs in soleus and pectineus muscles show small additions and deletions to parts of the NMJs 16,18, but sternocleidomastoid muscle shows only synapse size growth that appears to be related directly to increased muscle fiber diameter 17. Another example of the plastic nature of NMJs is seen at the synaptic vesicle release sites known as active zones. NMJ active zones are not stable structures. They are quickly altered by extracellular stimuli 19,20 and degenerate during aging 9,21. Interestingly, exercise can ameliorate degenerative changes in the presynaptic active zones of NMJs in aged rats,9 as will be described later in this review. The beneficial effects of exercise on maintenance and recovery of NMJs have been summarized previously 1,10–13,22. However, important findings elucidating the cellular and molecular mechanisms have been reported recently. The goal of this review is to highlight recent insights into the role of exercise in maintaining the integrity of NMJs.

Adult NMJs and exercise

Endurance training increases the synapse size of NMJs in adult mice 2 and rats 3,4 (Table 1). Exercise causes hypertrophy of the NMJs of extensor digitorum longus and gluteus maximus muscles in adult mice and rats 2,3,23. Soleus muscle, however, has been used more widely as a model to study NMJ adaptations to exercise, partly because of its homogeneous muscle fiber type composition and its antigravitational function 12. Exercise generally has been reported to cause hypertrophy of the NMJs of soleus muscles in adult mice and rats 2,4,24, and to increase the branching and complexity of presynaptic nerve terminals, 4 although 1 study reported that there is no effect in adult rats 3. Furthermore, different types of exercise, endurance versus resistance, produced slightly different results in soleus muscle in studies conducted by the same research group 4,6. Endurance training induced significant hypertrophy of the NMJs of soleus muscles, but resistance exercise induced only a trend of increase (not significant) of AChR cluster area. The result of resistance training in the soleus muscle is similar to the results for resistance training of genioglossus muscle in rats 9 and to the results of rat hypoglossal nerve stimulation to mimic resistance training of the tongue 25, neither of which causes an increase in the AChR cluster area. These results suggest that the effects of exercise on NMJs depend on the type of exercise performed.

Table 1.

Effects of exercise type and aging on neuromuscular junction size

| Exercise type | Muscle | Adult NMJ | Aged NMJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endurance | Extensor digitorum longus | Increase (mouse [2], rat [3]) | Decrease (mouse [2]) |

| Gluteus maximus | Increase (mouse [23]) | Decrease (mouse [23]) | |

| Soleus | Increase NMJ size (mouse [2], rat [4, 24]), No change (rat [3]) | No change (mouse [2], rat [24]) | |

|

| |||

| Resistance | Soleus | No change (rat [6]) | Unknown |

| Genioglossus | * No change (rat [25]) | No change (rat [9]), * decrease (rat [25]) | |

NMJ = neuromuscular junction.

In reference 25, chronic electrical stimulation was applied to the nerve to mimic a clinical exercise paradigm 144.

In contrast to increased physical activity causing hypertrophy of adult NMJs, decreased physical activity results in degenerative changes and nerve terminal sprouting in adult NMJs (reviewed in 12). For example, degenerative changes in NMJs occur upon exposure to zero gravity during space flight, during extended bed rest, or when the limbs of laboratory animals are fixed artificially to prevent use 12. These observations suggest that daily physical activity is required for maintenance of adult mammalian NMJs and prevention of degeneration.

Aged NMJs and exercise

Exercise has beneficial effects also on aged NMJs, even though the effects are different from those observed in younger adults (Table 1). Endurance training decreases AChR cluster size in the extensor digitorum longus muscle of aged mice and the gluteus maximus muscle of aged rat, which is the opposite effect of endurance training in younger adult animals 2,23. Furthermore, endurance training does not alter synapse size in the soleus muscle of aged mice 2 and rats 24. Similarly, isometric force training of the genioglossus muscle in aged rats does not alter synapse size, although it appears to have a beneficial effect on presynaptic active zones 9. Furthermore, endurance training in aged mice reduces age-related morphological alterations and denervation of NMJs in other hind limb muscles: tibialis anterior, gracilis, and gastrocnemius muscles 26. Importantly, time-lapse analysis in vivo reveals that endurance training of aged mice partially reverses the age-related alteration in NMJs. 26

These effects of exercise observed in aged animals should be interpreted with caution, because aged NMJs exhibit various degrees of denervation in different muscles 27. In young adult muscles, all NMJs are innervated, so analyses are limited to the adaptive changes in existing NMJs in response to increased activity. However, aged animals exhibit denervation in subpopulations of NMJs. Therefore, analyses of NMJs include the adaptive changes that occur in the existing NMJs and the reinnervation of the NMJs that were denervated prior to exercise. If analyses use aged muscles without denervation, for example the genioglossus muscle 9 or extraocular muscles 27, then the adaptive changes in aged NMJs would be the focus of analysis 9. These 2 approaches allow investigation of the potential therapeutic effects of exercise in maintaining and/or regenerating aged NMJs depending on the type of aged muscle.

In a recent study using aged genioglossus muscles, resistance training showed a beneficial effect on the presynaptic active zones in aged NMJs 9. Active zones are cytosolic structures needed for synaptic vesicle release 28–31. The active zone-specific protein Bassoon is absent in many NMJs of aged mice and rats, while nerve terminals still fully innervate the endplates 9,21. A loss of Bassoon can be seen prior to denervation of aged NMJs, which suggests that a loss of active zones may play a role in age-dependent degenerative changes in NMJs, including denervation. This is because NMJ denervation has been observed in young humans and mice that exhibit a loss of active zones resulting from gene mutations 31–33. This proposal is further supported by the finding that less active motor nerve terminals withdraw from NMJs when NMJ synaptic transmissions are attenuated under experimental conditions 34,35. Thus, these findings also suggest that NMJ synaptic activity and innervation maintenance are closely related. Importantly, 2 months of isometric force training reduces the active zone protein loss in the genioglossus muscle of aged rats 9. In trained-aged rats, the average level of Bassoon protein at the nerve terminals increases to the level observed in young adult NMJs, and the number of NMJs that do not contain a detectable level of Bassoon signal decreases significantly. This additional Bassoon protein in the trained-aged NMJs distributes to active zones, which may aid in functional recovery of NMJs.

Muscle fibers and exercise

Are these adaptive changes of NMJs a secondary effect of muscle fiber hypertrophy induced by exercise? Exercise causes muscle hypertrophy, and exercise-induced genes, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), have been shown to increase muscle fiber diameter 36. The role that these exercise-induced genes play in muscle hypertrophy has been reviewed in detail10,37. The NMJ size is coupled, to a certain degree, to muscle fiber size 17,38. However, aged NMJs respond differently than muscle fibers to exercise. Exercise increases muscle fiber size in the soleus muscle of aged rats 24,39, but the NMJ size does not increase 2,24. Furthermore, some of the exercise-based changes of NMJs cannot be explained merely by changes in muscle fiber diameter. Examples include increased active zone protein level 9,40, reduced denervation rates, reduced age-related morphological alterations in aged NMJs 26, and a reduction of AChR cluster size in extensor digitorum longus and gluteus maximus muscles of aged mice 2,23. Therefore, exercise induces NMJ hypertrophy partly by increasing muscle fiber diameter, but also by direct modification of NMJs.

Molecular mechanism underlying the exercise effect on NMJs

The beneficial effects of exercise are observed predominantly in trained muscles, and a systemic effect in non-trained muscles has not been observed 26,41 (also see 42). These results suggest that NMJ hypertrophy in exercised young adults and the increase in active zone protein levels in exercised aged NMJs are localized effects within the exercised muscles and motor neurons innervating exercised muscles. The molecular mechanisms through which exercise produces beneficial effects on NMJs have not been elucidated fully.

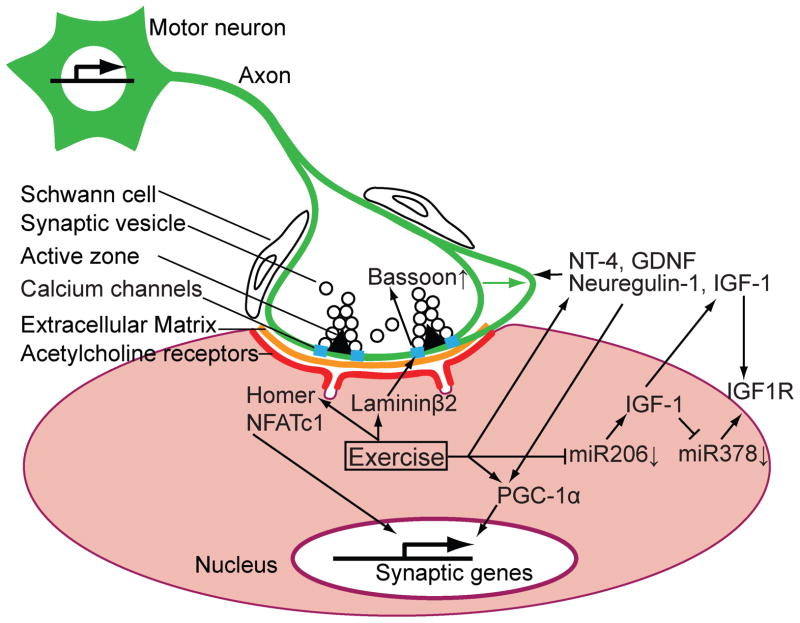

In human muscles, resistance training upregulates mRNA and protein expression levels of extracellular matrix molecules 41,43, including laminin β2 41 (Figure 1, Table 2). The exercise induced upregulation of laminin β2 expression may play a role in the effect of exercise that increases the level of active zone protein Bassoon in aged NMJs 9. The link between these 2 studies will be discussed below.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram showing genes and proteins controlled by exercise at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Solid arrows represent an upregulation or enhancement of RNAs or proteins by exercise. T-shaped arrows represent a suppression of RNAs or proteins by exercise. See text and tables for the modification mechanisms and functions of these RNAs and proteins by exercise. A motor neuron and its presynaptic terminal are indicated in green. The green arrow indicates hypertrophy or sprouting of the motor nerve terminal induced by exercise. Synaptic vesicles and voltage-dependent calcium channels accumulate near the active zone indicated using a black triangle, which depicts the electron dense material of the active zones detected by electron microscopy. A muscle fiber is indicated in pink with acetylcholine receptors indicated in red and synaptic extracellular matrix indicated in orange at the synaptic cleft. A junctional fold is indicated as a trough on the postsynaptic membrane. The relative size of the structures in this diagram is not in scale.

Table 2.

Effects of exercise on synaptic genes, NMJ morphology, and NMJ function.

| Signaling pathways, genes, and proteins | Effects of exercise | Effects on NMJ morphology and function |

|---|---|---|

| [Presynaptic active zone organizer] | ||

| Laminin β2 | Increases the level of extracellular matrix molecules, including laminin β2 (mRNA) in humans [41]. | |

| Bassoon | Reverts the Bassoon protein level at the presynaptic terminal of aged NMJs to young adult level [9]. | |

|

| ||

| [Neuregulin/PGC-1α] | ||

| Neuregulin-1 | Increases the phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of neuregulin-1 in skeletal muscle [78]. | Induces the expression of synaptic genes [80]. |

| PGC-1α | Increases the expression level of PGC-1α in humans [83] and rats [82]. | |

| AMPK | Increases AMPK activation in human [86,87]. | AMPK activates PGC-1α by directly phosphorylating it [88]. |

|

| ||

| [Neurotrophic factors] | ||

| IGF-1 | Increases the expression level of IGF-1 in human [90, 91]. | |

| miR-206 | Decreases the expression level of miR-206 in human [98]. | |

| NT-4 | Increases NT-4 mRNA level by electrical stimulation of sciatic nerves [105]. | |

| BDNF | Increases the expression level of BDNF [102]. | |

| GDNF | Increases the expression level of GDNF [102]. Increases the protein level of GDNF in the rat soleus muscle, but decreases in the extensor digitorum longus muscle [103]. |

|

|

| ||

| [Homer-NFATc1] | ||

| Homer | Increases protein level of Homer at postsynaptic side of NMJs [125]. | |

Laminin β2 is an extracellular matrix protein that is secreted by muscles and is concentrated specifically in the synaptic cleft of NMJs 44,45. Laminin β2 binds directly and specifically to P/Q- and N-type voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) 19. These VDCC pore-forming subunits bind to synaptic laminins that contain laminin β2 and do not bind to non-synaptic laminins, which contain laminin β1 19. Furthermore, synaptic laminins will bind to VDCCs that are highly concentrated at presynaptic terminals in NMJs (e.g., P/Q- and N-types) and not to other VDCCs [e.g., R- and L-type VDCCs (Cav1.2)] 19,46,47, which suggests that laminin β2 is an extracellular ligand of synaptic VDCCs. Interactions between laminin β2 and VDCCs lead to the clustering of VDCCs and presynaptic components in cultured motor neurons 19. In vivo studies provide compelling evidence that this extracellular interaction between laminin and VDCCs organizes the NMJ active zones. The number of active zones decreased when the interaction between the VDCCs and laminin β2 was perturbed in wild-type mice by infusing an inhibitor of this interaction 19. Moreover, P/Q- and N-type VDCCs double knockout mice exhibit specific defects in the number of active zones and docked synaptic vesicles, which were twice as severe as the defects observed in the P/Q- and N-type VDCC single knockout mice 19,48. Humans who carry laminin β2 mutations that result in active zone loss and denervation develop Pierson syndrome, an autosomal recessive movement disorder associated with microcoria, and nephrotic syndrome32,49. These data suggest that laminin β2 binds to synaptic VDCCs to organize the active zones.

P/Q-type VDCCs are distributed in a discrete punctate pattern within NMJs and preferentially co-localize with Bassoon9. It has been predicted that the VDCCs that trigger synaptic vesicle release are located at or in close proximity to active zones 50–55. The three-dimensional alignment of the P/Q-type VDCCs and Bassoon immunohistochemistry signals suggests that these co-localization spots are discrete active zones within NMJs 9. This proposal is also supported by rodent NMJ active zone studies that have used freeze fracture electron microscopy 56, electron microscope tomography 57,58, and electrophysiology 59. Importantly, this co-localization pattern of P/Q-type VDCCs and Bassoon in the NMJs is consistent with a report that identified direct binding between VDCCs and Bassoon 48. In addition, the active zone specific proteins Bassoon, CAST/Erc2, ELKS, and RIMs interact with the VDCC β subunits 48,60–62, which forms a tight complex with the pore-forming α subunits of the P/Q- and N-type VDCCs 63. VDCC α subunits also interact with the active zone proteins RIMs and Piccolo 64–66. These active zone proteins most likely form a large protein complex 67–70. Therefore, presynaptic VDCCs tether active zone proteins to the presynaptic membrane and form electron-dense material in the NMJ active zones. Taken together with the previous paragraph, these findings show that the muscle-derived laminin β2 organizes NMJ active zones from the extracellular side by anchoring the VDCC subunits and active zone protein complex.

NMJ active zones are maintained at a constant density as the NMJ matures but are degraded in aged animals 21. The level of Bassoon decreases in the NMJs of aged mice and rats 9,21. A lack of Bassoon is known to impair synaptic vesicle trafficking to presynaptic membranes in the central nervous system and sensory neurons 71–73. Furthermore, a lack of Bassoon decreases VDCC Ca2+ influx and weakens synaptic transmission, because the direct interaction between VDCCs and Bassoon enhances the P/Q-type VDCC function 9. This modification to VDCCs by Bassoon is similar to the effect of another active zone protein, RIM1, on VDCCs 60,61. These findings are consistent with the Bassoon-dependent increase in Ca2+ influx through L-type VDCCs in the inner hair cells of the auditory system 73. Furthermore, impaired synaptic transmission at NMJs is a known characteristic in human diseases and knockout mice associated with a decreased number of active zones 31,55,74. Therefore, the reduced Bassoon protein level in aged NMJs most likely weakens synaptic transmission. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that synaptic function is attenuated in aged NMJs compared with young adult NMJs, including stronger synaptic depression during repeated stimulation 75, reduction in the end-plate potential amplitude at the plateau level after repetitive stimulation 76, and a reduction in the frequency of miniature end-plate potentials 76,77. Taken together, these findings suggest that active zone protein loss may be a part of the molecular mechanism that causes the deterioration observed in aged NMJs.

Active zone deterioration in aged NMJs is ameliorated by muscle exercise. Two months of isometric force training rescued the loss of Bassoon in aged NMJs in the genioglossus muscle of two-year-old rats 9. Exercise training did not alter NMJ size, which suggests that the increase in the Bassoon immunohistochemistry signal in aged NMJs reflects an increase in the protein quantity in each nerve terminal 9. The mean intensity of the Bassoon immunohistochemistry signal in the NMJs of exercised aged rats is similar to the mean intensity observed in the young adult rats. Importantly, the improvement in Bassoon protein level observed in exercised aged NMJs is consistent with improvements observed using electrophysiology in NMJ function after endurance training in aged mice 23. In summary, exercise-induced upregulation of laminin β2 may play a role in preservation of active zones in aged NMJs, which most likely exerts a positive effect on NMJ synaptic transmission.

Other molecular mechanisms involved in the exercise effect on NMJs

Signaling cascades involving neuregulins and PGC-1α play a role in the beneficial effects of exercise (Figure 1, Table 2). Exercise increases the phosphorylation and proteolytic processing of a transmembrane isoform of the signaling molecule neuregulin-1 in skeletal muscle 78. Proteolytic cleavage of neuregulin-1 can also be induced by increasing the neuronal activity in cultured neurons 79. Neuregulin induces expression of synaptic genes in muscles, and this finding was confirmed in vivo using neuregulin1 heterozygote mice 80. Neuregulin-1 mediated upregulation of synaptic gene expression in muscles requires the transcription coactivator PGC-1α, phosphorylation of PGC-1α, and interaction of PGC-1α and GA-binding proteins 81. Furthermore, exercise increases the expression level of PGC-17α in rodents and humans 82,83, and elevated levels of PGC-1α increase the transcription of synaptic genes in cultured primary muscle cells 81. Additionally, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) may play a role in activating PGC-1α in response to exercise 84. AMPK is an energy-sensing enzyme 85 that is activated in skeletal muscles during exercise 86,87. AMPK phosphorylates PGC-1α directly, which is required for the PGC-1α-dependent induction of the PGC-1α promoter 88. Interestingly, knockout mice for the neuregulin1 isoform highly expressed in motor neurons (CRD-NRG-1) exhibit presynaptic defects in developing NMJs 89, which suggests that neuregulin signaling also plays a role on the presynaptic side of NMJs. In summary, these signaling cascades most likely play a role in the exercise-induced modification of NMJs.

Exercise induces expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 splice variants (a.k.a. mechano growth factor) in skeletal muscles 90,91 (Table 2). Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) preserves NMJs in a motor neuron disease mouse model 92, which suggests that IGF-1 also plays a role in the beneficial effects of exercise on NMJs. Interestingly, the expression level of IGF-1 is regulated negatively by microRNA (miR)-206 in the skeletal muscles of fish 93. Several miRs are highly expressed in skeletal muscles and are considered to be muscle specific, including miR-206 94. In human skeletal muscles, many miRs are regulated by exercise 95–97. For example, endurance training for 12 weeks significantly decreases the expression level of miR-206 98, which may increase the expression level of IGF-1. Additionally, IGF-1 inhibits expression of miR-378, and miR-378 negatively regulates the expression level of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) in mouse cardiomyocytes 99. Together, IGF-1 and muscle-specific miRs may play a role in the beneficial effects of exercise by enhancing the IGF-1 signaling pathway. This interesting potential role for the IGF-1 signaling cascade awaits further study in human skeletal muscles. It has also been reported that miR-206 promotes regeneration of NMJs in a motor neuron disease mouse model 100. The discrepancy between this positive role of miR-206 and the finding that exercise downregulates miR-206 is due potentially to the difference between motor neuron disease animals and healthy animals. Further investigation is needed to elucidate the role of miRs in exercise.

Exercise also upregulates transcription of several other neurotrophic factors 101–104 which have beneficial effects on NMJs (Table 2). The expression level of neurotrophin 4 (NT-4) is activity-dependent, and electrical stimulation of the sciatic nerve increases NT-4 expression in mouse skeletal muscles 105. Importantly, NT-4 receptor (TrkB) is expressed in motor neurons, and NT-4 induces the sprouting of motor nerve terminals in adult rats in vivo 105. These results demonstrate that increased NT-4 can explain, at least in part, the beneficial effects of exercise on NMJs. However, the role NT-4 plays in exercise-induced hypertrophy of the NMJs is unknown, because NMJ size was not measured in this study. Similarly, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) are upregulated in the rat soleus muscle by exercise 102,103. Therefore, the expression level of these factors in skeletal muscles is activity-dependent. These neurotrophic factors increase the survival of motor neurons 106–116. Furthermore, neurotrophins modulate the synaptic transmission efficiency of the NMJs in embryos and adults 117–121. In addition, GDNF increases the number of motor units and induces continuous synaptic remodeling of adult NMJs 122. These findings suggest that exercise induces expression of GDNF and BDNF, which increase the survival of the innervating motor neurons and have beneficial effects on NMJs in exercised muscles. Interestingly, the GDNF protein level is not upregulated uniformly by exercise and seems to be muscle specific, because it has been shown that GDNF is downregulated in the extensor digitorum longus muscle after exercise 103.

Other signaling proteins are also regulated by exercise. Homer is an adaptor protein that has a role in controlling the Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channel activity in skeletal muscles 123,124 and accumulates at postsynaptic sites in skeletal muscles 125. In human skeletal muscles, postsynaptic protein levels of Homer increase with exercise and decrease with bed rest,125 (Table 2). Homer2 binds directly to the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFATc1), and activated NFATc1 moves from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in exercised muscle 125. NFAT1c1 upregulates expression levels of synaptic genes, acetylcholinesterase, and utrophin, in skeletal muscles 126,127. Utrophin is a large cytoskeletal protein that accumulates preferentially at NMJs and participates in the maturation of the postsynaptic site 128–131. These findings suggest that Homer plays a role in the NFATc1-dependent signaling pathway to increase transcription of synaptic gene in exercised muscle.

Implications for treatment

The molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of exercise on NMJs are being elucidated, but knowledge gaps currently prevent complete reproduction of these benefits by pharmacological treatments. This review covers a subset of the genes, proteins, and signaling pathways that are modified by exercise, and transcriptome analyses have recently revealed a large number of genes that are controlled in response to increased physical activity in the spinal cord 132–134 and skeletal muscles 41–43,133,135–140. Tissue-specific and age-dependent differences in these responses are being revealed within skeletal muscle tissues, and thus, further mechanistic investigations are needed. As summarized in this review, exercise clearly has beneficial effects on the maintenance and regeneration of NMJs. The molecular mechanisms underlying these beneficial effects provide potential new therapeutic targets for motor neuron diseases, neuromuscular junction diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, and age-dependent degeneration of NMJs. Currently, many studies that manipulate signaling pathways related to exercise have focused their analyses mostly on muscles but not NMJs 84,141–143. The effects of exercise mimetics as pharmacological treatments of neuromuscular diseases have not yet been determined successfully. Therefore, it is anticipated that further research will yield methods to pharmacologically mimic, enhance, or modify these cellular and molecular mechanisms of exercise in order to enhance exercise-based interventions or replace them in individuals whose disabilities preclude exercise intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor Lawrence H Phillips, II for the invitation to write this review. The work in our laboratories are supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH, 1R01NS078214) and the Whitehall foundation to HN; NIH AG023549, NIH AG026491 to JAS; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to YM; and NIH-NCRR (P20 RR024214) and NIH-NICHD (HD02528) for core facility support.

Abbreviations

- AChR

acetylcholine receptor

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- GDNF

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor-1

- IGF1R

insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

- miR

microRNA

- NFATc1

nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- NMJs

neuromuscular junctions

- NT-4

neurotrophin 4

- PGC-1α

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α

- VDCCs

voltage dependent calcium channels

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Booth FW, Chakravarthy MV, Gordon SE, Spangenburg EE. Waging war on physical inactivity: using modern molecular ammunition against an ancient enemy. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(1):3–30. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00073.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andonian MH, Fahim MA. Effects of endurance exercise on the morphology of mouse neuromuscular junctions during ageing. J Neurocytol. 1987;16(5):589–599. doi: 10.1007/BF01637652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waerhaug O, Dahl HA, Kardel K. Different effects of physical training on the morphology of motor nerve terminals in the rat extensor digitorum longus and soleus muscles. Anat Embryol. 1992;186(2):125–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00174949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deschenes MR, Maresh CM, Crivello JF, Armstrong LE, Kraemer WJ, Covault J. The effects of exercise training of different intensities on neuromuscular junction morphology. J Neurocytol. 1993;22(8):603–615. doi: 10.1007/BF01181487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanda K, Hashizume K. Effects of long-term physical exercise on age-related changes of spinal motoneurons and peripheral nerves in rats. Neurosci Res. 1998;31(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(98)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deschenes MR, Judelson DA, Kraemer WJ, Meskaitis VJ, Volek JS, Nindl BC, Harman FS, Deaver DR. Effects of resistance training on neuromuscular junction morphology. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23(10):1576–1581. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200010)23:10<1576::aid-mus15>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanford JA, Vorontsova E, Fowler SC. The relationship between isometric force requirement and forelimb tremor in the rat. Physiol Behav. 2000;69(3):285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guggenmos DJ, Barbay S, Bethel-Brown C, Nudo RJ, Stanford JA. Effects of tongue force training on orolingual motor cortical representation. Behav Brain Res. 2009;201(1):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimune H, Numata T, Chen J, Aoki Y, Wang Y, Starr MP, Mori Y, Stanford JA. Active zone protein Bassoon co-localizes with presynaptic calcium channel, modifies channel function, and recovers from aging related loss by exercise. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e38029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. The role of exercise and PGC1alpha in inflammation and chronic disease. Nature. 2008;454(7203):463–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panenic R, Gardiner PF. The case for adaptability of the neuromuscular junction to endurance exercise training. Can J Appl Physiol. 1998;23(4):339–360. doi: 10.1139/h98-019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson MH, Deschenes MR. The neuromuscular junction: anatomical features and adaptations to various forms of increased, or decreased neuromuscular activity. The International journal of neuroscience. 2005;115(6):803–828. doi: 10.1080/00207450590882172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.English AW, Wilhelm JC, Sabatier MJ. Enhancing recovery from peripheral nerve injury using treadmill training. Ann Anat. 2011;193(4):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Thompson WJ. Nerve Terminal Growth Remodels Neuromuscular Synapses in Mice following Regeneration of the Postsynaptic Muscle Fiber. J Neurosci. 2011;31(37):13191–13203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2953-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deschenes MR, Britt AA, Gomes RR, Booth FW, Gordon SE. Recovery of neuromuscular junction morphology following 16 days of spaceflight. Synapse. 2001;42(3):177–184. doi: 10.1002/syn.10001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wigston DJ. Remodeling of neuromuscular junctions in adult mouse soleus. J Neurosci. 1989;9(2):639–647. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-02-00639.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balice-Gordon RJ, Lichtman JW. In vivo visualization of the growth of pre- and postsynaptic elements of neuromuscular junctions in the mouse. J Neurosci. 1990;10(3):894–908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-03-00894.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill RR, Robbins N, Fang ZP. Plasticity of presynaptic and postsynaptic elements of neuromuscular junctions repeatedly observed in living adult mice. J Neurocytol. 1991;20(3):165–182. doi: 10.1007/BF01186990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishimune H, Sanes JR, Carlson SS. A synaptic laminin-calcium channel interaction organizes active zones in motor nerve terminals. Nature. 2004;432(7017):580–587. doi: 10.1038/nature03112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meriney SD, Wolowske B, Ezzati E, Grinnell AD. Low calcium-induced disruption of active zone structure and function at the frog neuromuscular junction. Synapse. 1996;24(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199609)24:1<1::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Mizushige T, Nishimune H. Active zone density is conserved during synaptic growth but impaired in aged mice. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520(2):434–452. doi: 10.1002/cne.22764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandervoort AA. Aging of the human neuromuscular system. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25(1):17–25. doi: 10.1002/mus.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fahim MA. Endurance exercise modulates neuromuscular junction of C57BL/6NNia aging mice. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83(1):59–66. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deschenes MR, Roby MA, Glass EK. Aging influences adaptations of the neuromuscular junction to endurance training. Neuroscience. 2011;190:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson AM, Connor NP. Effects of electrical stimulation on neuromuscular junction morphology in the aging rat tongue. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(2):203–211. doi: 10.1002/mus.21819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valdez G, Tapia JC, Kang H, Clemenson GD, Jr, Gage FH, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Attenuation of age-related changes in mouse neuromuscular synapses by caloric restriction and exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(33):14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002220107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valdez G, Tapia JC, Lichtman JW, Fox MA, Sanes JR. Shared Resistance to Aging and ALS in Neuromuscular Junctions of Specific Muscles. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e34640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuoka T, Engel AG, Lang B, Newsom-Davis J, Prior C, Wray DW. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: I. Early morphological effects of IgG on the presynaptic membrane active zones. Ann Neurol. 1987;22(2):193–199. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambert EH, Elmqvist D. Quantal components of end-plate potentials in the myasthenic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1971;183:183–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb30750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Propst JW, Ko CP. Correlations between active zone ultrastructure and synaptic function studied with freeze-fracture of physiologically identified neuromuscular junctions. J Neurosci. 1987;7(11):3654–3664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03654.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maselli RA, Ng JJ, Anderson JA, Cagney O, Arredondo J, Williams C, Wessel HB, Abdel-Hamid H, Wollmann RL. Mutations in LAMB2 causing a severe form of synaptic congenital myasthenic syndrome. J Med Genet. 2009;46(3):203–208. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zenker M, Aigner T, Wendler O, Tralau T, Muntefering H, Fenski R, Pitz S, Schumacher V, Royer-Pokora B, Wuhl E, Cochat P, Bouvier R, Kraus C, Mark K, Madlon H, Dotsch J, Rascher W, Maruniak-Chudek I, Lennert T, Neumann LM, Reis A. Human laminin beta2 deficiency causes congenital nephrosis with mesangial sclerosis and distinct eye abnormalities. Human molecular genetics. 2004;13(21):2625–2632. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noakes PG, Gautam M, Mudd J, Sanes JR, Merlie JP. Aberrant differentiation of neuromuscular junctions in mice lacking s-laminin/laminin beta 2. Nature. 1995;374(6519):258–262. doi: 10.1038/374258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buffelli M, Burgess RW, Feng G, Lobe CG, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Genetic evidence that relative synaptic efficacy biases the outcome of synaptic competition. Nature. 2003;424(6947):430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature01844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balice-Gordon RJ, Lichtman JW. Long-term synapse loss induced by focal blockade of postsynaptic receptors. Nature. 1994;372(6506):519–524. doi: 10.1038/372519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruas JL, White JP, Rao RR, Kleiner S, Brannan KT, Harrison BC, Greene NP, Wu J, Estall JL, Irving BA, Lanza IR, Rasbach KA, Okutsu M, Nair KS, Yan Z, Leinwand LA, Spiegelman BM. A PGC-1alpha Isoform Induced by Resistance Training Regulates Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy. Cell. 2012;151(6):1319–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sartorelli V, Fulco M. Molecular and cellular determinants of skeletal muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Sci STKE. 2004;2004(244):re11. doi: 10.1126/stke.2442004re11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balice-Gordon RJ, Breedlove SM, Bernstein S, Lichtman JW. Neuromuscular junctions shrink and expand as muscle fiber size is manipulated: in vivo observations in the androgen-sensitive bulbocavernosus muscle of mice. J Neurosci. 1990;10(8):2660–2671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-08-02660.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klitgaard H, Brunet A, Maton B, Lamaziere C, Lesty C, Monod H. Morphological and biochemical changes in old rat muscles: effect of increased use. J Appl Physiol. 1989;67(4):1409–1417. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.4.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishimune H. Molecular mechanism of active zone organization at vertebrate neuromuscular junctions. Molecular neurobiology. 2012;45(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8216-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon PM, Liu D, Sartor MA, IglayReger HB, Pistilli EE, Gutmann L, Nader GA, Hoffman EP. Resistance exercise training influences skeletal muscle immune activation: a microarray analysis. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(3):443–453. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00860.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catoire M, Mensink M, Boekschoten MV, Hangelbroek R, Muller M, Schrauwen P, Kersten S. Pronounced effects of acute endurance exercise on gene expression in resting and exercising human skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e51066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen YW, Hubal MJ, Hoffman EP, Thompson PD, Clarkson PM. Molecular responses of human muscle to eccentric exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95(6):2485–2494. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01161.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanes JR, Hall ZW. Antibodies that bind specifically to synaptic sites on muscle fiber basal lamina. J Cell Biol. 1979;83(2 Pt 1):357–370. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunter DD, Shah V, Merlie JP, Sanes JR. A laminin-like adhesive protein concentrated in the synaptic cleft of the neuromuscular junction. Nature. 1989;338(6212):229–234. doi: 10.1038/338229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uchitel OD, Protti DA, Sanchez V, Cherksey BD, Sugimori M, Llinas R. P-type voltage-dependent calcium channel mediates presynaptic calcium influx and transmitter release in mammalian synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(8):3330–3333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosato Siri MD, Uchitel OD. Calcium channels coupled to neurotransmitter release at neonatal rat neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1999;514 ( Pt 2):533–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.533ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen J, Billings SE, Nishimune H. Calcium channels link the muscle-derived synapse organizer laminin beta2 to Bassoon and CAST/Erc2 to organize presynaptic active zones. J Neurosci. 2011;31(2):512–525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3771-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zenker M, Tralau T, Lennert T, Pitz S, Mark K, Madlon H, Dotsch J, Reis A, Muntefering H, Neumann LM. Congenital nephrosis, mesangial sclerosis, and distinct eye abnormalities with microcoria: an autosomal recessive syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A(2):138–145. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pumplin DW, Reese TS, Llinas R. Are the presynaptic membrane particles the calcium channels? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78(11):7210–7213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robitaille R, Adler EM, Charlton MP. Strategic location of calcium channels at transmitter release sites of frog neuromuscular synapses. Neuron. 1990;5(6):773–779. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90336-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Llinas R, Sugimori M, Silver RB. Microdomains of high calcium concentration in a presynaptic terminal. Science. 1992;256(5057):677–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1350109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haydon PG, Henderson E, Stanley EF. Localization of individual calcium channels at the release face of a presynaptic nerve terminal. Neuron. 1994;13(6):1275–1280. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neher E. Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20(3):389–399. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urbano FJ, Piedras-Renteria ES, Jun K, Shin HS, Uchitel OD, Tsien RW. Altered properties of quantal neurotransmitter release at endplates of mice lacking P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(6):3491–3496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437991100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellisman MH, Rash JE, Staehelin LA, Porter KR. Studies of excitable membranes. II. A comparison of specializations at neuromuscular junctions and nonjunctional sarcolemmas of mammalian fast and slow twitch muscle fibers. J Cell Biol. 1976;68(3):752–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.68.3.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagwaney S, Harlow ML, Jung JH, Szule JA, Ress D, Xu J, Marshall RM, McMahan UJ. Macromolecular connections of active zone material to docked synaptic vesicles and presynaptic membrane at neuromuscular junctions of mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513(5):457–468. doi: 10.1002/cne.21975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fukunaga H, Engel AG, Lang B, Newsom-Davis J, Vincent A. Passive transfer of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome with IgG from man to mouse depletes the presynaptic membrane active zones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80(24):7636–7640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.24.7636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruiz R, Cano R, Casanas JJ, Gaffield MA, Betz WJ, Tabares L. Active zones and the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles at the neuromuscular junction of the mouse. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2000–2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4663-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kiyonaka S, Wakamori M, Miki T, Uriu Y, Nonaka M, Bito H, Beedle AM, Mori E, Hara Y, De Waard M, Kanagawa M, Itakura M, Takahashi M, Campbell KP, Mori Y. RIM1 confers sustained activity and neurotransmitter vesicle anchoring to presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(6):691–701. doi: 10.1038/nn1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uriu Y, Kiyonaka S, Miki T, Yagi M, Akiyama S, Mori E, Nakao A, Beedle AM, Campbell KP, Wakamori M, Mori Y. Rab3-interacting molecule gamma isoforms lacking the Rab3-binding domain induce long lasting currents but block neurotransmitter vesicle anchoring in voltage-dependent P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(28):21750–21767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.101311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Billings SE, Clarke GL, Nishimune H. ELKS1 and Ca2+ channel subunit beta4 interact and colocalize at cerebellar synapses. Neuroreport. 2012;23(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834e7deb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shibasaki T, Sunaga Y, Fujimoto K, Kashima Y, Seino S. Interaction of ATP sensor, cAMP sensor, Ca2+ sensor, and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel in insulin granule exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):7956–7961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shibasaki T, Sunaga Y, Seino S. Integration of ATP, cAMP, and Ca2+ Signals in Insulin Granule Exocytosis. Diabetes. 2004;53(suppl_3):S59–62. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaeser PS, Deng L, Fan M, Sudhof TC. RIM genes differentially contribute to organizing presynaptic release sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(29):11830–11835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209318109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takao-Rikitsu E, Mochida S, Inoue E, Deguchi-Tawarada M, Inoue M, Ohtsuka T, Takai Y. Physical and functional interaction of the active zone proteins, CAST, RIM1, and Bassoon, in neurotransmitter release. J Cell Biol. 2004;164(2):301–311. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang X, Hu B, Zieba A, Neumann NG, Kasper-Sonnenberg M, Honsbein A, Hultqvist G, Conze T, Witt W, Limbach C, Geitmann M, Danielson H, Kolarow R, Niemann G, Lessmann V, Kilimann MW. A protein interaction node at the neurotransmitter release site: domains of Aczonin/Piccolo, Bassoon, CAST, and Rim converge on the N-terminal domain of Munc13–1. J Neurosci. 2009;29(40):12584–12596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1255-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carlson SS, Valdez G, Sanes JR. Presynaptic calcium channels and alpha3-integrins are complexed with synaptic cleft laminins, cytoskeletal elements and active zone components. J Neurochem. 2010;115(3):654–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muller CS, Haupt A, Bildl W, Schindler J, Knaus HG, Meissner M, Rammner B, Striessnig J, Flockerzi V, Fakler B, Schulte U. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(34):14950–14957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005940107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hallermann S, Fejtova A, Schmidt H, Weyhersmuller A, Silver RA, Gundelfinger ED, Eilers J. Bassoon speeds vesicle reloading at a central excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2010;68(4):710–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mukherjee K, Yang X, Gerber SH, Kwon HB, Ho A, Castillo PE, Liu X, Sudhof TC. Piccolo and bassoon maintain synaptic vesicle clustering without directly participating in vesicle exocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(14):6504–6509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002307107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frank T, Rutherford MA, Strenzke N, Neef A, Pangrsic T, Khimich D, Fejtova A, Gundelfinger ED, Liberman MC, Harke B, Bryan KE, Lee A, Egner A, Riedel D, Moser T. Bassoon and the synaptic ribbon organize Ca2+ channels and vesicles to add release sites and promote refilling. Neuron. 2010;68(4):724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knight D, Tolley LK, Kim DK, Lavidis NA, Noakes PG. Functional analysis of neurotransmission at beta2-laminin deficient terminals. J Physiol. 2003;546(Pt 3):789–800. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith DO. Acetylcholine storage, release and leakage at the neuromuscular junction of mature adult and aged rats. J Physiol. 1984;347:161–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Banker BQ, Kelly SS, Robbins N. Neuromuscular transmission and correlative morphology in young and old mice. J Physiol. 1983;339:355–377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gutmann E, Hanzlikova V, Vysokocil F. Age changes in cross striated muscle of the rat. J Physiol. 1971;216(2):331–343. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lebrasseur NK, Cote GM, Miller TA, Fielding RA, Sawyer DB. Regulation of neuregulin/ErbB signaling by contractile activity in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284(5):C1149–1155. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00487.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ozaki M, Itoh K, Miyakawa Y, Kishida H, Hashikawa T. Protein processing and releases of neuregulin-1 are regulated in an activity-dependent manner. J Neurochem. 2004;91(1):176–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sandrock AW, Dryer SE, Rosen KM, Gozani SN, Kramer R, Theill LE, Fischbach GD. Maintenance of Acetylcholine Receptor Number by Neuregulins at the Neuromuscular Junction in Vivo. Science. 1997;276(5312):599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Handschin C, Kobayashi YM, Chin S, Seale P, Campbell KP, Spiegelman BM. PGC-1alpha regulates the neuromuscular junction program and ameliorates Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Genes Dev. 2007;21(7):770–783. doi: 10.1101/gad.1525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goto M, Terada S, Kato M, Katoh M, Yokozeki T, Tabata I, Shimokawa T. cDNA Cloning and mRNA analysis of PGC-1 in epitrochlearis muscle in swimming-exercised rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274(2):350–354. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Russell AP, Feilchenfeldt J, Schreiber S, Praz M, Crettenand A, Gobelet C, Meier CA, Bell DR, Kralli A, Giacobino JP, Deriaz O. Endurance training in humans leads to fiber type-specific increases in levels of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha in skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2003;52(12):2874–2881. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carey AL, Kingwell BA. Novel pharmacological approaches to combat obesity and insulin resistance: targeting skeletal muscle with ‘exercise mimetics’. Diabetologia. 2009;52(10):2015–2026. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Richter EA, Ruderman NB. AMPK and the biochemistry of exercise: implications for human health and disease. Biochem J. 2009;418(2):261–275. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wojtaszewski JF, Nielsen P, Hansen BF, Richter EA, Kiens B. Isoform-specific and exercise intensity-dependent activation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2000;528(Pt 1):221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fujii N, Hayashi T, Hirshman MF, Smith JT, Habinowski SA, Kaijser L, Mu J, Ljungqvist O, Birnbaum MJ, Witters LA, Thorell A, Goodyear LJ. Exercise induces isoform-specific increase in 5′AMP-activated protein kinase activity in human skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273(3):1150–1155. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(29):12017–12022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wolpowitz D, Mason TB, Dietrich P, Mendelsohn M, Talmage DA, Role LW. Cysteine-rich domain isoforms of the neuregulin-1 gene are required for maintenance of peripheral synapses. Neuron. 2000;25(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang S, Alnaqeeb M, Simpson H, Goldspink G. Cloning and characterization of an IGF-1 isoform expressed in skeletal muscle subjected to stretch. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1996;17(4):487–495. doi: 10.1007/BF00123364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hameed M, Orrell RW, Cobbold M, Goldspink G, Harridge SD. Expression of IGF-I splice variants in young and old human skeletal muscle after high resistance exercise. J Physiol. 2003;547(Pt 1):247–254. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.032136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dobrowolny G, Giacinti C, Pelosi L, Nicoletti C, Winn N, Barberi L, Molinaro M, Rosenthal N, Musaro A. Muscle expression of a local Igf-1 isoform protects motor neurons in an ALS mouse model. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(2):193–199. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yan B, Zhu CD, Guo JT, Zhao LH, Zhao JL. miR-206 regulates the growth of the teleost tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) through the modulation of IGF-1 gene expression. J Exp Biol. 2013;216(Pt 7):1265–1269. doi: 10.1242/jeb.079590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCarthy JJ, Esser KA, Peterson CA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Evidence of MyomiR network regulation of beta-myosin heavy chain gene expression during skeletal muscle atrophy. Physiol Genomics. 2009;39(3):219–226. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00042.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Drummond MJ, McCarthy JJ, Fry CS, Esser KA, Rasmussen BB. Aging differentially affects human skeletal muscle microRNA expression at rest and after an anabolic stimulus of resistance exercise and essential amino acids. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(6):E1333–1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90562.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aoi W, Naito Y, Mizushima K, Takanami Y, Kawai Y, Ichikawa H, Yoshikawa T. The microRNA miR-696 regulates PGC-1{alpha} in mouse skeletal muscle in response to physical activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298(4):E799–806. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00448.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Davidsen PK, Gallagher IJ, Hartman JW, Tarnopolsky MA, Dela F, Helge JW, Timmons JA, Phillips SM. High responders to resistance exercise training demonstrate differential regulation of skeletal muscle microRNA expression. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110(2):309–317. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00901.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nielsen S, Scheele C, Yfanti C, Akerstrom T, Nielsen AR, Pedersen BK, Laye MJ. Muscle specific microRNAs are regulated by endurance exercise in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 20):4029–4037. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knezevic I, Patel A, Sundaresan NR, Gupta MP, Solaro RJ, Nagalingam RS, Gupta M. A novel cardiomyocyte-enriched microRNA, miR-378, targets insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor: implications in postnatal cardiac remodeling and cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(16):12913–12926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.331751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, Qi X, McAnally J, Elliott JL, Bassel-Duby R, Sanes JR, Olson EN. MicroRNA-206 Delays ALS Progression and Promotes Regeneration of Neuromuscular Synapses in Mice. Science. 2009;326(5959):1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1181046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cote MP, Azzam GA, Lemay MA, Zhukareva V, Houle JD. Activity-dependent increase in neurotrophic factors is associated with an enhanced modulation of spinal reflexes after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(2):299–309. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dupont-Versteegden EE, Houle JD, Dennis RA, Zhang J, Knox M, Wagoner G, Peterson CA. Exercise-induced gene expression in soleus muscle is dependent on time after spinal cord injury in rats. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(1):73–81. doi: 10.1002/mus.10511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.McCullough MJ, Peplinski NG, Kinnell KR, Spitsbergen JM. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor protein content in rat skeletal muscle is altered by increased physical activity in vivo and in vitro. Neuroscience. 2011;174:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schaser AJ, Stang K, Connor NP, Behan M. The effect of age and tongue exercise on BDNF and TrkB in the hypoglossal nucleus of rats. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226(1):235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Funakoshi H, Belluardo N, Arenas E, Yamamoto Y, Casabona A, Persson H, Ibanez CF. Muscle-derived neurotrophin-4 as an activity-dependent trophic signal for adult motor neurons. Science. 1995;268(5216):1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.7770776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dohrmann U, Edgar D, Thoenen H. Distinct neurotrophic factors from skeletal muscle and the central nervous system interact synergistically to support the survival of cultured embryonic spinal motor neurons. Dev Biol. 1987;124(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Oppenheim RW, Yin QW, Prevette D, Yan Q. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues developing avian motoneurons from cell death. Nature. 1992;360(6406):755–757. doi: 10.1038/360755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sendtner M, Holtmann B, Kolbeck R, Thoenen H, Barde YA. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor prevents the death of motoneurons in newborn rats after nerve section. Nature. 1992;360(6406):757–759. doi: 10.1038/360757a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yan Q, Elliott J, Snider WD. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor rescues spinal motor neurons from axotomy-induced cell death. Nature. 1992;360(6406):753–755. doi: 10.1038/360753a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Henderson CE, Camu W, Mettling C, Gouin A, Poulsen K, Karihaloo M, Rullamas J, Evans T, McMahon SB, Armanini MP, et al. Neurotrophins promote motor neuron survival and are present in embryonic limb bud. Nature. 1993;363(6426):266–270. doi: 10.1038/363266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koliatsos VE, Clatterbuck RE, Winslow JW, Cayouette MH, Price DL. Evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor is a trophic factor for motor neurons in vivo. Neuron. 1993;10(3):359–367. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90326-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Henderson CE, Phillips HS, Pollock RA, Davies AM, Lemeulle C, Armanini M, Simmons L, Moffet B, Vandlen RA, Simpson LC, et al. GDNF: a potent survival factor for motoneurons present in peripheral nerve and muscle. Science. 1994;266(5187):1062–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.7973664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Buj-Bello A, Buchman VL, Horton A, Rosenthal A, Davies AM. GDNF is an age-specific survival factor for sensory and autonomic neurons. Neuron. 1995;15(4):821–828. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Oppenheim RW, Houenou LJ, Johnson JE, Lin LF, Li L, Lo AC, Newsome AL, Prevette DM, Wang S. Developing motor neurons rescued from programmed and axotomy-induced cell death by GDNF. Nature. 1995;373(6512):344–346. doi: 10.1038/373344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yan Q, Matheson C, Lopez OT. In vivo neurotrophic effects of GDNF on neonatal and adult facial motor neurons. Nature. 1995;373(6512):341–344. doi: 10.1038/373341a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Liu X, Jaenisch R. Severe peripheral sensory neuron loss and modest motor neuron reduction in mice with combined deficiency of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin 3 and neurotrophin 4/5. Dev Dyn. 2000;218(1):94–101. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<94::AID-DVDY8>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stoop R, Poo MM. Potentiation of transmitter release by ciliary neurotrophic factor requires somatic signaling. Science. 1995;267(5198):695–699. doi: 10.1126/science.7839148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang T, Xie K, Lu B. Neurotrophins promote maturation of developing neuromuscular synapses. J Neurosci. 1995;15(7 Pt 1):4796–4805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang XH, Poo MM. Potentiation of developing synapses by postsynaptic release of neurotrophin-4. Neuron. 1997;19(4):825–835. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80964-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. Neurotrophins improve neuromuscular transmission in the adult rat diaphragm. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(3):381–386. doi: 10.1002/mus.10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pousinha PA, Diogenes MJ, Ribeiro JA, Sebastiao AM. Triggering of BDNF facilitatory action on neuromuscular transmission by adenosine A2A receptors. Neurosci Lett. 2006;404(1–2):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Keller-Peck CR, Feng G, Sanes JR, Yan Q, Lichtman JW, Snider WD. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor administration in postnatal life results in motor unit enlargement and continuous synaptic remodeling at the neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2001;21(16):6136–6146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yuan JP, Kiselyov K, Shin DM, Chen J, Shcheynikov N, Kang SH, Dehoff MH, Schwarz MK, Seeburg PH, Muallem S, Worley PF. Homer binds TRPC family channels and is required for gating of TRPC1 by IP3 receptors. Cell. 2003;114(6):777–789. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00716-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Stiber JA, Zhang ZS, Burch J, Eu JP, Zhang S, Truskey GA, Seth M, Yamaguchi N, Meissner G, Shah R, Worley PF, Williams RS, Rosenberg PB. Mice lacking Homer 1 exhibit a skeletal myopathy characterized by abnormal transient receptor potential channel activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(8):2637–2647. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01601-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Salanova M, Bortoloso E, Schiffl G, Gutsmann M, Belavy DL, Felsenberg D, Furlan S, Volpe P, Blottner D. Expression and regulation of Homer in human skeletal muscle during neuromuscular junction adaptation to disuse and exercise. Faseb J. 2011;25(12):4312–4325. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cohen TV, Randall WR. NFATc1 activates the acetylcholinesterase promoter in rat muscle. J Neurochem. 2004;90(5):1059–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Angus LM, Chakkalakal JV, Mejat A, Eibl JK, Belanger G, Megeney LA, Chin ER, Schaeffer L, Michel RN, Jasmin BJ. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling, together with GABP and peroxisome PGC-1{alpha}, drives utrophin gene expression at the neuromuscular junction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289(4):C908–917. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00196.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Love DR, Hill DF, Dickson G, Spurr NK, Byth BC, Marsden RF, Walsh FS, Edwards YH, Davies KE. An autosomal transcript in skeletal muscle with homology to dystrophin. Nature. 1989;339(6219):55–58. doi: 10.1038/339055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ohlendieck K, Ervasti JM, Matsumura K, Kahl SD, Leveille CJ, Campbell KP. Dystrophin-related protein is localized to neuromuscular junctions of adult skeletal muscle. Neuron. 1991;7(3):499–508. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90301-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Grady RM, Merlie JP, Sanes JR. Subtle neuromuscular defects in utrophin-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 1997;136(4):871–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Grady RM, Teng H, Nichol MC, Cunningham JC, Wilkinson RS, Sanes JR. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90(4):729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Perreau VM, Adlard PA, Anderson AJ, Cotman CW. Exercise-induced gene expression changes in the rat spinal cord. Gene expression. 2005;12(2):107–121. doi: 10.3727/000000005783992115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ferraiuolo L, De Bono JP, Heath PR, Holden H, Kasher P, Channon KM, Kirby J, Shaw PJ. Transcriptional response of the neuromuscular system to exercise training and potential implications for ALS. J Neurochem. 2009;109(6):1714–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hashimoto K, Honda A, Hayashi Y, Inuzuka T, Satoh M, Hozumi I. DNA microarray analysis of transcriptional responses of mouse spinal cords to physical exercise. J Toxicol Sci. 2009;34(4):445–448. doi: 10.2131/jts.34.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Carson JA, Nettleton D, Reecy JM. Differential gene expression in the rat soleus muscle during early work overload-induced hypertrophy. Faseb J. 2002;16(2):207–209. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0544fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mu J, Barton ER, Birnbaum MJ. Selective suppression of AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle: update on ‘lazy mice’. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31(Pt 1):236–241. doi: 10.1042/bst0310236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wu H, Gallardo T, Olson EN, Williams RS, Shohet RV. Transcriptional analysis of mouse skeletal myofiber diversity and adaptation to endurance exercise. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24(8):587–592. doi: 10.1023/b:jure.0000009968.60331.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Choi S, Liu X, Li P, Akimoto T, Lee SY, Zhang M, Yan Z. Transcriptional profiling in mouse skeletal muscle following a single bout of voluntary running: evidence of increased cell proliferation. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99(6):2406–2415. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00545.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Teran-Garcia M, Rankinen T, Koza RA, Rao DC, Bouchard C. Endurance training-induced changes in insulin sensitivity and gene expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(6):E1168–1178. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00467.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bye A, Hoydal MA, Catalucci D, Langaas M, Kemi OJ, Beisvag V, Koch LG, Britton SL, Ellingsen O, Wisloff U. Gene expression profiling of skeletal muscle in exercise-trained and sedentary rats with inborn high and low VO2max. Physiol Genomics. 2008;35(3):213–221. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90282.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ort T, Gerwien R, Lindborg KA, Diehl CJ, Lemieux AM, Eisen A, Henriksen EJ. Alterations in soleus muscle gene expression associated with a metabolic endpoint following exercise training by lean and obese Zucker rats. Physiol Genomics. 2007;29(3):302–311. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00257.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, Embler E, Wang YX, Banayo E, Mihaylova MM, Nelson MC, Zou Y, Juguilon H, Kang H, Shaw RJ, Evans RM. AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008;134(3):405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Booth FW, Laye MJ. Lack of adequate appreciation of physical exercise’s complexities can pre-empt appropriate design and interpretation in scientific discovery. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 23):5527–5539. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Robbins J, Gangnon RE, Theis SM, Kays SA, Hewitt AL, Hind JA. The effects of lingual exercise on swallowing in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(9):1483–1489. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]