Abstract

Background. Studies on the effect of intensive insulin therapy (IIT) in septic patients with hyperglycemia have given inconsistent results. The primary purpose of this meta-analysis was to evaluate whether it is effective in reducing mortality. Methods. We searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, clinicaltrials.gov, and relevant reference lists up to September 2013 and including randomized controlled trials that compared IIT with conventional glucose management in septic patients. Study quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. And our primary outcome measure was pooled in the random effects model. Results. We identified twelve randomized controlled trials involving 4100 patients. Meta-analysis showed that IIT did not reduce any of the outcomes: overall mortality (risk ratio [RR] = 0.98, 95% CI [0.85, 1.15], P = 0.84), 28-day mortality (RR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.40, 1.10], P = 0.11), 90-day mortality (RR = 1.10, 95% CI [0.97, 1.26], P = 0.13), ICU mortality (RR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.77, 1.14], P = 0.52), hospital mortality (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.86, 1.11], P = 0.71), severity of illness, and length of ICU stay. Conversely, the incidence of hypoglycemia was markedly higher in the IIT (RR = 2.93, 95% CI [1.69, 5.06], P = 0.0001). Conclusions. For patients with sepsis, IIT and conservative glucose management show similar efficacy, but ITT is associated with a higher incidence of hypoglycemia.

1. Introduction

Sepsis has been a long withstanding issue in modern medicine that in too many instances leads to mortality. Every year in the United States there are approximately 750,000 documented cases, of which at least 225,000 are fatal [1]. Though there have been advances in intensive care, the mortality rate of patients with sepsis has remained between 20% and 30% over the past three decades [1, 2]. One pathophysiological component in septic patients is hypermetabolism, including perturbations of glucose metabolism resulting in hyperglycemia [3].

Hyperglycemia is prevalent in ICU patients, especially those with sepsis [4–6]. Hyperglycemia is associated with many adverse outcomes, including immune disorder, oxidative stress, susceptibility to infection, and endothelial dysfunction [7, 8]. Its impact is believed by research that has found hyperglycemia to be independently associated with increased mortality in patients with sepsis because it enhances the inflammatory response [6, 9]. Some randomized controlled clinical trials have attempted to determine whether intensive insulin therapy targeted on establishing normoglycemia could benefit septic patients [10–14].

In 2001, a randomized controlled trial showed that intensive treatment with insulin (80–110 mg/dL) resulted in a lower hospital mortality in the surgical ICU, which was attributed to a reduction of mortality in patients with sepsis [15]. Conversely, the VISEP study, the first to specifically investigate intensive insulin therapy for septic patients, found no significant reduction in mortality [10]. Then, further randomized controlled trials failed to replicate the mortality benefit in septic patients [16, 17]. Despite this continuing debate, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign included an upper limit for blood glucose of 180 mg/dL in their guidelines based upon systematic reviews of studies involving critically ill patients [18]. Although sepsis is the chief cause of death in ICUs, whether the impact and safety of intensive insulin therapy in septic patients are the same as those in critically ill patients is uncertain.

In order to clarify this matter, we conducted a meta-analysis to assess the use of intensive insulin therapy in managing glycemic control for septic patients. The primary purpose was to evaluate the effects of tight glycemic control on mortality stratified into four subgroups (90-day and 28-day mortality and hospital and ICU mortality).

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We searched for randomized controlled trials of intensive insulin therapy targeting euglycemia among septic patients in PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and clinicaltrials.gov dating up to September 2013 without language restriction. We used the exploded Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “insulin,” “blood glucose,” and “hypoglycemic agents,” with the text words “hyperglycemia,” “insulin,” “blood glucose,” and “glycemic control,” for the intensive insulin filter. The MeSH term “sepsis” with the text words “sepsis,” “severe sepsis,” “septic shock,” and “septicemia” for the sepsis filter. Additionally, a highly sensitive search strategy described in the Cochrane Handbook was utilized for the randomized controlled trials filter [19]. The MeSH terms and text words were combined with the Boolean operator OR, and then the three filters were combined with the Boolean AND operator. We also checked the reference lists of retrieved reviews and clinical trials to identify additional studies.

2.2. Study Selection

Two investigators independently reviewed all of the titles and abstracts. Included articles met the following criteria: (1) trials had a randomized controlled clinical design, with or without blinding; (2) patients were adults with sepsis; (3) the intensive insulin therapy group had a targeted glucose concentration of ≤150 mg/dL, and the control group had a higher glucose level; and (4) the outcome measures included at least one of the following: mortality, severity of illness, length of ICU stay, and hypoglycemia (≤40 mg/dL). We also included data from trials in critically ill patients if the data concerning sepsis could be extracted.

2.3. Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

Independently, the same two investigators abstracted the data and assessed the methodological quality of eligible trials. If there was any disagreement, a third investigator participated in a group discussion and made the final decision. The abstracted data was as follows: first author, year of publication, region or country, number of study site, sample size, population, patient age, history of diabetes mellitus, initial glucose level, targeted glucose level, and achieved mean glucose value. The primary outcome was mortality with a preference for 90-day mortality. If this was not reported in the outcome, we used hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, or ICU mortality, in that order. The secondary outcomes were severity of illness, length of ICU stay, and hypoglycemia. We also stratified mortality by 90-day and 28-day mortality, as well as hospital and ICU mortality in subgroup analyses.

The methodological quality was formally evaluated using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool, which incorporates random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias [19]. Each item was stratified into one of three categories: (1) high risk, which represented low quality, (2) low risk, which represented high quality, or (3) unclear, in which there was insufficient information to judge or the study did not involve this outcome.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We used the Review Manager software to conduct the statistical analyses [20]. For each outcome measure, we used the relative risk (RR) for dichotomous data and the standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous data. We used a random-effect model for all analyses which provides a more conservative pooled estimate than a fixed-effect model, considering the anticipated clinical heterogeneity among eligible articles [21]. Some data were presented with means and 95% confidence intervals, necessitating that we calculate standard deviations from the data provided. We assessed the heterogeneity among studies using Cochran's Q-test (P < 0.10 for statistical significance) and the I 2 statistic (I 2 value >50% for substantial heterogeneity). To eliminate the heterogeneity, we conducted either a sensitivity analysis or subgroup analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

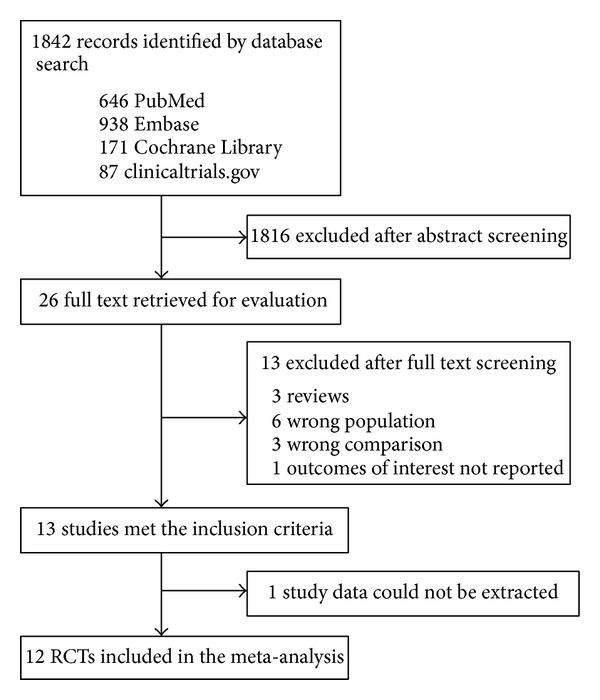

Our predefined search strategy yielded a total of 1,842 abstracts (Figure 1). After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we excluded 1,816 studies because they were nonrandomized controlled trials, not specific to septic patients or pertained to interventions other than intensive insulin therapy. We checked the full text of the remaining 26 articles. One trial that met our inclusion criteria was excluded because the data were presented in diagrams from which we were unable to abstract values [22]. No additional studies were found in the screened reference lists. Finally, 12 randomized controlled trials were included in our meta-analysis [10–14, 16, 17, 23–27]. One trial was only an abstract, despite contacting the authors to request a copy of the full article [23].

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The 12 randomized controlled trials included 4,100 patients in all, of whom 2,094 were assigned to the intensive insulin group and 2,006 to the control group. The details of the included studies are listed in Table 1. For the intervention, all the trials used tight glycemic control (80–110 mg/dL) except for one trial used that used two glycemic subcategories: 80–110 mg/dL or 120–150 mg/dL [23]. Because our inclusion criterion was an intensive insulin therapy group targeting a glucose concentration of ≤150 mg/dL, we combined the data of the two glycemic subcategories for mortality analysis. The mean glucose concentration of included patients varied significantly among eligible trials, from 130 mg/dL to 216 mg/dL. The proportion of patients with septic shock ranged widely (32.7–100%). In 3 trials, the baseline parameters of the septic patients were undocumented in the intensive and the control groups [17, 23, 24]. Most of the included trials used a specific method of random sequence generation (Table 2). None of the trials met the “blinding of participants and personnel” bias criterion and thus were rated as high-risk. On the contrary, all studies were identified as low risk because they did not have “incomplete outcome data.”

Table 1.

Characteristics of included randomized controlled trials.

| First author, year (country) | Number of study sites | Sample size | Population, % | Mean age, (years) | Diabetic, % | Initial glucose, mg/dL | Glucose goal, mg/dL | Glucose achieved, mean (SD), mg/dL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cappi 2012 (Brazil) [14] | 1 | 63 | Severe sepsis Septic shock |

53 | 24 | IIT 144 [97–182]∗ Control 141 [101–160]∗ | IIT 80–110 Control 140–180 |

IIT 99 (18) Control 155 (39.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| COIITSS 2010 (France) [16] | 11 | 509 | Septic shock 100 | 64 | NA | IIT 216 (NA) Control 204 (NA) | IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 120–140 Control 140–160 |

|

| ||||||||

| Savioli 2009 (Italy) [12] | 3 | 90 | Severe sepsis 65.6 Septic shock 34.4 |

61 | 13.3 | IIT 175 (101) Control 160 (74) | IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 112 (23) Control 159 (31) |

|

| ||||||||

| Iapichino 2008 (Italy) [11] | 3 | 72 | Severe sepsis 19.4 Septic shock 80.6 |

62.3 | 17 | IIT 137 (45) Control 151.7 (36.6) | IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 110 (17) Control 163 (29) |

|

| ||||||||

| Brunkhorst 2008 (Germany) [10] | 18 | 537 | Septic shock 100 | 64.6 | 30 | IIT 130 [108–167]∗ Control 138 [111–184]∗ | IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 112 (NA) Control 151 (NA) |

|

| ||||||||

| Ellger 2008 (Belgium) [25] | 1 | 950 | Severe sepsis 51.4 Septic shock 48.6 |

62 | 14 | IIT 163 (73) Control 161 (70) | IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 106 (26) Control 150 (30) |

|

| ||||||||

| Yu 2005 (China) [13] | 1 | 55 | Sepsis | 46 | NA | IIT 153 (61) Control 151 (65) | IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 103 (22) Control 198 (29) |

|

| ||||||||

| Dong 2009 (China) [27] | 1 | 27 | Septic shock 100 | 44 | 0 | IIT157 (45) Control 159 (39.6) | IIT 74–110 Control 112–150 |

IIT 108 (27) Control 148 (34) |

|

| ||||||||

| NICE-SUGAR 2009 (Australia and New Zealand—Canada) [17] | 42 | 1299 | Severe sepsis Septic shock |

60.2 | 20.1 | IIT 146 (52.3) Control 144 (49.1) | IIT 81–108 Control 180 or less |

IIT 115 (18) Control 144 (23) |

|

| ||||||||

| Arabi 2008 (Saudi Arabia) [24] | 1 | 122 | Severe sepsis Septic shock |

52.4 | 40.0 | IIT 195 (75) Control 211 (81) |

IIT 80–110 Control 180–200 |

IIT 115 (18) Control 171 (34) |

|

| ||||||||

| Zhang 2008 (China) [26] | 1 | 22 | Sepsis | 66.3 | 27.5 | IIT 165 (55) Control 200 (100) | IIT 80–110 Control 130–150 |

IIT 119 (7.6) Control 141 (7.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Jin 2009# (China) [23] | 14 | 356 | Severe sepsis Septic shock |

65.7 | NA | IIT NA Control NA |

IIT 80–110; 120–150 Control 180–200 |

IIT 80–110: 99 (31); 120–150: 133 (34) Control 189 (40) |

IIT: intensive insulin therapy; NA: not available from article or author.

*Median (interquartile range).

#Abstract only.

Table 2.

Risk of bias in included randomized controlled trials.

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cappi 2012 [14] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| COIITSS 2010 (France) [16] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High riska |

| Savioli 2009 [12] | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Iapichino 2008 [11] | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk |

| Brunkhorst 2008 [10] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | High riska,b |

| Ellger 2008 [25] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Yu 2005 [13] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk |

| Dong 2009 [27] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk |

| NICE-SUGAR 2009 (Australia and New Zealand—Canada) [17] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High riskc |

| Arabi 2008 [24] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High riskd |

| Zhang 2008 [26] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk |

| Jin 2009∗ [23] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

*Abstract only.

NA: not available from article or author.

aThe two treatment groups differ in the use of medications other than insulin.

bIntensive insulin therapy was terminated early because of increasing hypoglycemic events.

cInclusion used subjective criteria.

dIt had a different baseline.

3.3. Primary Outcome: Mortality

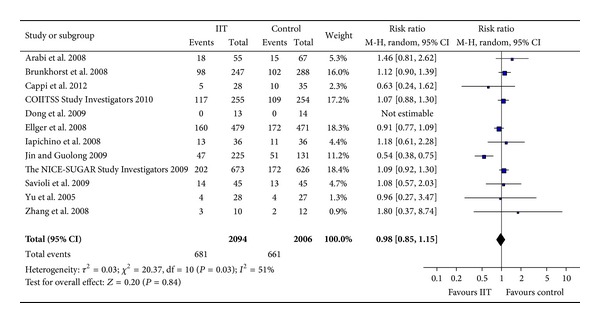

The all-cause mortality was reported in the 12 randomized controlled trials [10–14, 16, 17, 23–27]. There were 681/2,094 (32.5%) deaths in the intensive insulin intervention group and 661/2,006 (33%) in the control group. Meta-analysis showed that the rate of death did not differ significantly between the two groups (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.85, 1.15], P = 0.84) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot with all-cause mortality showing no significant difference between IIT and control group (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.85, 1.15]). IIT: intensive insulin therapy. CI: confidence interval. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel.

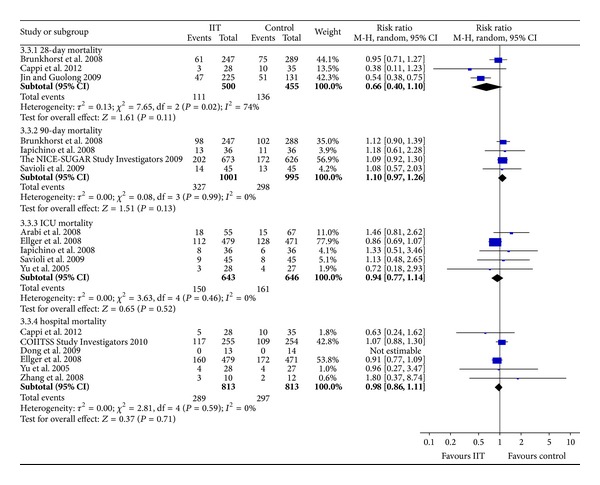

In the subgroup analysis, there was no significant difference in 28-day mortality (RR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.40, 1.10], P = 0.11), 90-day mortality (RR = 1.10, 95% CI [0.97, 1.26], P = 0.13), ICU mortality (RR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.77, 1.14], P = 0.52), or hospital mortality (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.86, 1.11], P = 0.71) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis showing no significant difference between IIT and control groups, with mortality being stratified into 28-day, 90-day, ICU, and hospital mortality. IIT: intensive insulin therapy. CI: confidence interval. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel.

The statistical heterogeneity was substantial for all-cause mortality (I 2 = 51%; P = 0.03) and for 28-day mortality (I 2 = 74%; P = 0.02). Because we could not acquire the full text of the study by Jin and Guolong [23], we did not have sufficient information to evaluate its methodological quality. Therefore, we excluded this trial and the heterogeneity for all-cause mortality was resolved (I 2 = 0%; P = 0.51). The heterogeneity was still significant for 28-day mortality. We noted that the Cappi trial had a wide confidence interval due to its small sample size [14]. Thus, we identified this trial as an outlier in the 28-day mortality. Even with this adjustment, the results of all-cause mortality (RR = 1.05, 95% CI [0.96, 1.14], P = 0.33) and 28-day mortality (RR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.71, 1.27], P = 0.74) did not change significantly.

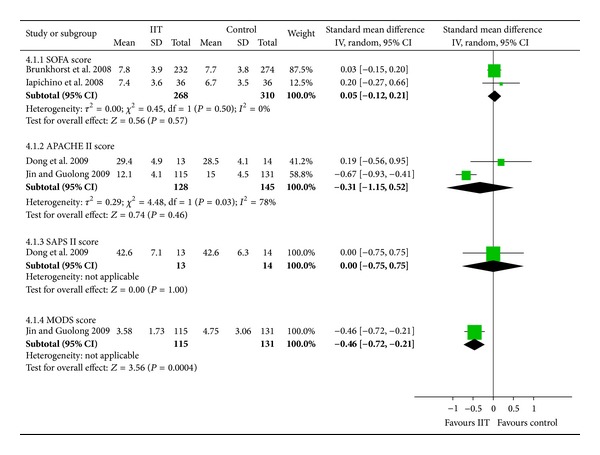

3.4. Secondary Outcomes: Severity of Illness, Length of ICU Stay, and Hypoglycemic Events

The included trials used the SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment) score, APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) score, SAPS II (Simplified Acute Physiology Score II), and MODS (Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score) to evaluate severity of illness after intensive insulin therapy. Five trials reported SOFA score [10–13, 16], two studies reported APACHE II score, and only the MODS [23] and SAPS II [27] scores were reported in only one study each. The data about SOFA score could only be extracted from two trials that included 578 participants [10, 11]. The pooled estimate in the intensive insulin group was similar to that in the control group (SMD = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.21], P = 0.57) with no statistical heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%; P = 1.00) (Figure 4). Similarly, there was no significant difference in APACHE II score (P = 0.46) and SAPS II (P = 1.00). The MODS was lower in the intensive insulin group, but its methodological quality was low. This suggests that intensive insulin therapy does not reduce the severity of sepsis.

Figure 4.

Forest plot with severity of illness showing no significant difference between IIT and control groups in SOFA, APACHE II, and SAPS II scores, with a reduction of MODS score with IIT. IIT: intensive insulin therapy. SD: standard deviation. CI: confidence interval. IV: inverse variance.

Five trials reported the length of ICU stay as an outcome [10, 11, 16, 23, 26]. It should be noted that in four of the trials the data were presented as the median (interquartile range) [10, 11, 16, 26], each with no statistically significant difference between the intensive insulin and control groups. The remaining trial with unclear methodological quality found that intensive insulin therapy resulted in a shorter ICU stay, but the result was dubious [23]. We did not merge the medians (interquartile range), because we could not determine whether they had a normal distribution [19].

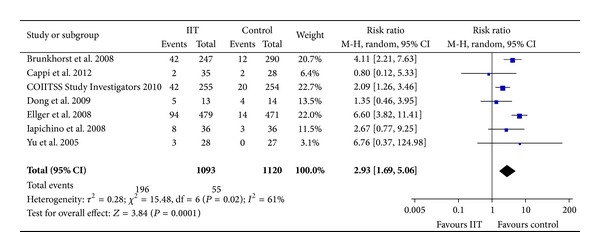

For the occurrence of hypoglycemia, we extracted data from seven trials including 2,213 participants [10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 25, 27] (Figure 5). There were 196/1,093 (17.9%) hypoglycemic events in the intensive insulin group and 55/1,120 (4.9%) in the control group. The intensive insulin group had a higher rate of hypoglycemia than the control group (RR = 2.93, 95% CI [1.69, 5.06], P = 0.0001), and there was substantial heterogeneity across the trials (I 2 = 61%, P = 0.02). We identified the Ellger et al. trial as an outlier [25], and its exclusion resolved the heterogeneity (I 2 = 19%, P = 0.29) but did not change the pooled estimate (RR = 2.44, 95% CI [1.59, 3.72], P < 0.0001).

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing that IIT increased the risk of hypoglycemia. IIT: intensive insulin therapy. CI: confidence interval. M-H: Mantel-Haenszel.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Through performing several sensitivity analyses (the trials with “low risk” of “random sequence generation” and “allocation concealment”, the trials with >500 patients, the trials with septic shock data, and studies with excluding unclear baseline characteristics) [17, 23, 24], the overall effect size was found to change minimally regardless of mortality or hypoglycemia (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis.

| Outcome | Number of studies |

Number of patients |

RR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk of random sequence generation and allocation concealment | ||||

| Mortality | 6 | 3478 | 1.04 (0.95–1.15) | 0.40 |

| Hypoglycemia | 4 | 2059 | 3.27 (1.62–6.57) | 0.0009 |

| Trials containing >500 patients | ||||

| Mortality | 4 | 3293 | 1.04 (0.94–1.14) | 0.44 |

| Hypoglycemia | 3 | 1996 | 3.81 (1.89–7.69) | 0.0002 |

| Patients with similar baseline | ||||

| Mortality | 9 | 1910 | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | 0.97 |

| Hypoglycemia | 7 | 2213 | 2.93 (1.69–5.06) | 0.0001 |

| Patients with septic shock | ||||

| Mortality | 4 | 1533 | 1.03 (0.89–1.18) | 0.69 |

| Hypoglycemia | 4 | 1535 | 2.97 (1.72–5.12) | <0.0001 |

RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval.

3.6. Publication Bias

We were unable to evaluate the publication bias, in part, due to the appearance of heterogeneity and also due to the small number of the included trials in each comparison.

4. Discussion

We conducted a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of intensive insulin therapy for septic patients, which showed no reduction of mortality overall nor in any of the subgroups (28-day and 90-day mortality; ICU and hospital mortality). Likewise, in terms of the severity of illness, the intensive insulin group did not show a statistically significant difference from the control. Though one trial found that the intensive insulin therapy group had a shorter ICU stay than the control group, its methodological quality was vague. Due to the data format, we could not merge the other studies with the length of ICU stay. Intensive insulin therapy, however, notably increased the episodes of hypoglycemia. We found substantial heterogeneity in the pooled analysis of mortality and hypoglycemia, but the results remained the same when the heterogeneity was removed using sensitivity analysis.

During the past 30 years, no effective new therapies appeared, despite that our understanding of the pathophysiologic features of sepsis has advanced [28]. A number of observational studies indicate that hyperglycemia is associated with a higher mortality rate, in particular, sepsis-induced hyperglycemia rather than mortality due to preexisting diabetes mellitus [6]. The landmark randomized controlled trial showed that intensive insulin therapy (targeting 80–110 mg/dL) reduced hospital mortality in septic patients [15], so clinicians enthusiastically received it as an effective therapy for these patients. Unfortunately, subsequent randomized controlled trials failed to confirm this beneficial effect.

Several prior reviews investigated the effect of intensive insulin therapy (IIT) for a general population of ICU patients [29–31]. Though we obtained similar results regarding the effect of IIT on mortality and risk of hypoglycemia, there are some differences in our findings compared with the prior reviews. The previous reviews concentrated on a general population of ICU patients. Solyemez Wiener et al. [29], Kansagara et al. [30], and Griesdale et al.'s [31] trials were grouped by type of ICU (medical ICU, surgical ICU, and mixed ICU). Kansagara et al.'s [30] trials were also grouped by type of patients (myocardial infarction and stroke); however, we focused on patients with sepsis. Even though septic patients are intermixed with other ICU patients, they possess distinct treatment and prognostic and clinical outcomes as compared with other ICU patients. Therefore, the effect of intensive insulin therapy for ICU patients is not necessarily congruent with the effect for septic patients. In addition, we classified the outcome of mortality into four subgroups (90-day, 28-day, hospital, and ICU mortality) and added the outcome of severity of illness and the length of ICU stay that were not evaluated in the prior reviews.

We included one specific study [25] that contained a database of two randomized controlled trials [15, 32], which used identical protocols and were implemented at the same center but one year apart. Thus, we treated these studies as a consecutive study. This study [25] showed that intensive insulin therapy reduced the ICU mortality in septic patients who stayed in the ICU for at least three days, but there was no statistically significant difference in septic patients who stayed for less than three days. They performed this subgroup analysis to specifically consider patients whose intensive care was limited or who were withdrawn from intensive care within 3 days of admission to the ICU. Another trial, the Brunkhorst et al. trial [10], showed no effect of intensive insulin on mortality in septic patients who stayed in the ICU at least three or five days. The remaining trials did not stratify by the length of stay in the ICU. Taking the authentic clinical practice environment into consideration, we pooled the overall ICU stay and found no significant difference.

Perhaps the failure to find a benefit with intensive insulin therapy can be attributed to several factors. It remains unclear whether hyperglycemia is a cause of increased mortality or is just a marker of an increased risk of death; it may even be a normal response [6]. Finfer's [33] latest review states that “Until quite recently stress hyperglycemia was seen as a normal and possibly beneficial physiological response to promote cellular glucose uptake” (pp: 1–6).

In agreement with previous studies, our meta-analysis demonstrated that intensive insulin therapy carries a markedly increased risk of hypoglycemia. Hypoglycemia has been reported to have an independent association with increased mortality in patients with sepsis [34, 35]. Considering the increased risk of death due to increased hypoglycemia and the findings that intensive insulin therapy does not reduce mortality, the use of IIT as a strategy to maintain normoglycemia remains unclear.

Septic patients are apt to suffer from a striking increase in blood glucose variability, which causes endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and organ dysfunction [6, 9, 36, 37]. Though the mean blood glucose concentration is similar among trials, the degree of glucose variability may be quite different. Several observational studies have shown that blood glucose variability is independently associated with an increased mortality rate, even more than continuous hyperglycemia [9, 35]. The glycemic lability index, which is calculated from continuous glucose monitoring, reveals the inherent variability better than the standard deviation of the mean blood glucose value [35]. The included trials mainly used sampling at a predefined time, rather than monitoring 24-hour continuous glucose levels, resulting in insufficient data to determine the relationship between glucose variability and mortality rate.

There are several limitations to our meta-analysis. Septic patients who survive to hospital discharge still have a high risk of death in the following months and years, which has been suggested in many studies [38]. The NICE SUGAR trial found that intensive insulin therapy increased mortality compared with the control group at 90 days, but not at 28 days [17]. Furthermore, the VISEP study, which found that intensive insulin therapy did not reduce mortality in septic patients, was discontinued early due to an excess risk for hypoglycemia [10]. Trials included in our meta-analysis mainly contained data gathered before hospital discharge and follow-up was limited. Therefore, our results may not be appropriate for long-term prognosis.

The glucose target range of the most trials in this meta-analysis was 80–110 mg/dL. Perhaps, a result favoring intensive insulin therapy could have been found to occur if a higher concentration range was used in the intensive insulin group, in comparison with uncontrolled hyperglycemia. Restricted by the lack of adequate data, we were not able to stratify trials based on the type of ICU and the proportion of calories provided parenterally or to evaluate secondary outcome measures, such as severity of illness, length of ICU stay, and cost. Also, there is the possibility of publication bias in our review.

Unfortunately, none of the included randomized controlled trials used blinding of participants and personnel. Several trials had few mortality events, so we could not detect small differences between groups. Furthermore, the patient characteristics, blood glucose control, and coexisting interventions varied across the included studies.

5. Conclusion

Overall, the results of our meta-analysis suggest that intensive insulin therapy provides no benefit for septic patients. The highly sensitive search strategy, searching multiple databases and clinicaltrials.gov, searching publications written in any language, and performing subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses, provides strength and rigor for our meta-analysis. Future reviews of septic patients may require individual patient data and more data that captures outcome measures.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar G, Kumar N, Taneja A, et al. Nationwide trends of severe sepsis in the 21st century (2000–2007) Chest. 2011;140(5):1223–1231. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor JH, Beilman GJ. Hyperglycemia in the intensive care unit: no longer just a marker of illness severity. Surgical Infections. 2005;6(2):233–245. doi: 10.1089/sur.2005.6.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inzucchi SE. Management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(18):1903–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp060094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krinsley JS. Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2003;78(12):1471–1478. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leonidou L, Michalaki M, Leonardou A, et al. Stress-induced hyperglycemia in patients with severe sepsis: a compromising factor for survival. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2008;336(6):467–471. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318176abb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS, Preiser J-C. Stress hyperglycaemia. The Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1798–1807. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCowen KC, Malhotra A, Bistrian BR. Stress-induced hyperglycemia. Critical Care Clinics. 2001;17(1):107–124. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waeschle RM, Moerer O, Hilgers R, Herrmann P, Neumann P, Quintel M. The impact of the severity of sepsis on the risk of hypoglycaemia and glycaemic variability. Critical Care. 2008;12(5, article R129) doi: 10.1186/cc7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(2):125–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iapichino G, Albicini M, Umbrello M, et al. Tight glycemic control does not affect asymmetric-dimethylarginine in septic patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2008;34(10):1843–1850. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savioli M, Cugno M, Polli F, et al. Tight glycemic control may favor fibrinolysis in patients with sepsis. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37(2):424–431. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819542da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu W-K, Li W-Q, Wang X-D, et al. Influence and mechanism of a tight control of blood glucose by intensive insulin therapy on human sepsis. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2005;43(1):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cappi SB, Noritomi DT, Velasco IT, Curi R, Loureiro TCA, Soriano FG. Dyslipidemia: a prospective controlled randomized trial of intensive glycemic control in sepsis. Intensive Care Medicine. 2012;38(4):634–641. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2458-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(19):1359–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.COIITSS Study Investigators. Corticosteroid treatment and intensive insulin therapy for septic shock in adults-a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(17):341–348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(13):1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Critical Care Medicine. 2013;41(2):580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green S, PT Higgins J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5. 1. 0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program], Version 5. 2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

- 21.Berlin JA, Laird NM, Sacks HS, Chalmers TC. A comparison of statistical methods for combining event rates from clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1989;8(2):141–151. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polli F, Savioli M, Cugno M, et al. Effects of recombinant human activated protein C on the fibrinolytic system of patients undergoing conventional or tight glycemic control. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2009;75(7-8):417–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Y, Guolong C. A multicentre study on intensive insulin therapy of severe sepsis and septic shock patients in ICU-collaborative study group on IIT in Zhejiang province, china. Intensive Care Medicine. 2009;35(Supplement 1, article 86S) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arabi YM, Dabbagh OC, Tamim HM, et al. Intensive versus conventional insulin therapy: a randomized controlled trial in medical and surgical critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(12):3190–3197. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f21aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellger B, Westphal M, Stubbe HD, Van Den Heuvel I, Van Aken H, Van Den Berghe G. Glycemic control in sepsis and septic shock. Friend or foe? Anaesthesist. 2008;57(1):43–48. doi: 10.1007/s00101-007-1285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang R-L, He W, Li T, et al. Evaluation of optimal goal of glucose control in critically ill patients. Chinese Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;16(4):204–208. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong S-M, Qin Y-J, Gao Y-F. The influence of intensive insulin therapy on hemodynamics in patients with septic shock. Chinese Critical Care Medicine. 2009;21(5):290–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angus DC. The search for effective therapy for sepsis: back to the drawing board? JAMA—Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(23):2614–2615. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soylemez Wiener R, Wiener DC, Larson RJ. Benefits and risks of tight glucose control in critically ill adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA—Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(8):933–944. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kansagara D, Fu R, Freeman M, Wolf F, Helfand M. Intensive insulin therapy in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154(4):268–282. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griesdale DE, de Souza RJ, van Dam RM, et al. Intensive insulin therapy and mortality among critically ill patients: a meta-analysis including NICE-SUGAR study data. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009;180(8):821–827. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(5):449–461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finfer S. Clinical controversies in the management of critically ill patients with severe sepsis-Resuscitation fluids and glucose control. Virulence. 2013;4(8):1–6. doi: 10.4161/viru.25855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park S, Kim DG, Suh GY, et al. Mild hypoglycemia is independently associated with increased risk of mortality in patients with sepsis: a 3-year retrospective observational study. Critical Care. 2012;16(5, article R189) doi: 10.1186/cc11674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ali NA, O’Brien JM, Dungan K, et al. Glucose variability and mortality in patients with sepsis. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(8):2316–2321. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181810378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirasawa H, Oda S, Nakamura M. Blood glucose control in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;15(33):4132–4136. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(14):1681–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(21):840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]