Abstract

BACKGROUND

Recombinant xenografts of human cells growing in immunocompromised rodents are widely used for studying stem cell biology, tumor biology, and epithelial to mesenchyme transitions. Of critical importance is the correct interpretation of the cellular composition of such xenografts.

METHODS

Here we present a rapid and robust method employing protein nucleic acid (PNA) FISH probes to dual-label centromeres and telomeres (Cen/Tel FISH). Such labeling allows unambiguous discrimination between human, mouse, and rat cells in paraffin-embedded tissue sections, providing significant advantages over current methods used to discern human versus rodent cell types.

RESULTS

Using an in vivo prostatic developmental system where rat embryonic urogenital sinus mesenchyme is recombined with human prostate epithelial organoids and grown in an immunocompromised mouse, Cen/Tel FISH documents that all three species contribute to the development of glandular structures.

CONCLUSIONS

The method is an indispensable tool to analyze xenograft/host interactions and prevent misinterpretation of data using tissue recombination approaches.

Keywords: heterospecies recombinants, prostate, telomeres

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1980s, Cunha et al. described an experimental system where inductive embryonic urogenital sinus mesenchyme (UGSM) could be used to drive prostatic differentiation of admixed epithelial cells when implanted together under the renal capsule of immunocompromised mice [1,2]. The urogenital sinus (UGS) is the embryonic anlagen from which the prostate develops, and before mouse embryonic day 17 (E17; day E18 in the rat) the UGS can be removed and physically divided into epithelium (UGSE) and mesenchyme. This system is widely utilized to study numerous aspects of normal and abnormal prostate development and carcinogenesis, particularly growth factor and hormonal signaling pathways and mesenchymal–epithelial interactions [3–6]. Recently, UGSM has been shown to induce human ES cells and human stem cells to form prostatic structures in vivo [7,8]. This method involves the heterospecies ex vivo combination of rat or mouse UGSM with rat, mouse, or human epithelial cells; such recombinants are implanted and grown in an immunocompromised mouse host [2,9]. After a period of in vivo growth, the implant is resected and examined histologically, often revealing a variety of epithelial structures, some of which resemble prostatic glands and ducts embedded in stromal tissue. For meaningful conclusions to be drawn from such studies, it is of paramount importance that the species of origin of any resulting tissue structures be correctly determined. For example, in the UGSM recombination model, glandular structures could arise from several sources, including (1) the human epithelial cells implanted in the original graft (usually the desired result); (2) rodent epithelium derived from contaminating UGSE; (3) local kidney epithelial cells of the murine host; (4) circulating murine host pluripotent cells; or (5) transdifferentiating host or UGSM nonepithelial cells.

Here we present a simple, rapid and robust, and immunologically compatible method for discriminating the species of origin for human and rat cells implanted, either separately or in combination, in nude mice by exploiting species-specific differences in telomeric and centromeric DNA sequences. Such a method takes advantage of the unique centromeric genome sequences as well as the vast differences in telomere length between human and inbred rodent strains. Surprisingly, we document the presence of host mouse-derived glandular structures. Such mouse-derived glands are morphologically indistinguishable from rat and human glands and also express markers commonly found in human and rat prostate epithelia.

MATERIALS ANDMETHODS

Cells and Materials

Primary human prostate cells were isolated from persons undergoing radical prostatectomy at our institution according to an IRB-approved protocol. Dissociation of prostate tissue has been previously described [10]. Briefly, 18-gauge biopsy needle cores (Bard, Covington, GA) of prostate tissue were digested overnight at 37°C in collagenase solution [0.28% Collagenase I (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 1% DNAse I (Sigma), 10% FCS, 1× antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco-Invitrogen), in RPMI-1640 media]. The following day, the cell suspension was washed in 1× PBS, and epithelial organoids were isolated by a threefold density sedimentation, whereby cells in 10 ml of PBS were allowed to settle for 10 min at room temperature, and the top 9 ml of media (containing fibroblasts) removed. Prostate epithelial organoids were washed twice with PBS and recombined with rat UGSM.

UGSM Isolation and Tissue Recombination

All animal studies were performed under the guidance of IACUC-approved protocols. UGSM was isolated from E17 embryos of timed-pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) according to previously reported protocols [9,11,12]. UGSM was dissociated into single cells using 0.1% Collagenase B (Boehringer-Manheim, Indianapolis, IN) in DMEM + 10% FCS at 37°C for 2 hr. The single UGSM cells were washed three times in DMEM + 10% FCS and counted. UGSM cells were recombined with human epithelial organoids at a ratio of 2:1 in accordance with previous reports [13,14]. Tissue recombinants were embedded in 10 μl of Type I collagen (BD Biosciences) that consisted of 88% Collagen solution, 2% 1 N NaOH, and 10% of 10× PBS solution which hardened upon warming to room temperature. The recombinant implants were overlaid with DMEM + 10% FCS and 1 nM R1881 and incubated at 37°C overnight, then implanted under the renal capsule of 4- to 6-week-old male athymic nude mice using aseptic surgical techniques (a detailed protocol for renal capsule grafting can be found at http://mammary.nih.gov/tools/mousework/Cunha001/index.html). After 12 weeks the implants were excised, fixed in formalin, paraffin embedded and sectioned for analysis.

Centromere/Telomere FISH

Slide preparation was performed without protease digestion as previously described [15]. Briefly, 5 μm tissue sections were deparaffinized, hydrated through a graded ethanol series, immersed for 1 min in 1% Tween-20 followed by heat-induced target retrieval for 15 min in citrate buffer (Target Unmasking Solution; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA Cat# H-3300) using a vegetable steamer. Slides were cooled to room temperature for 5 min, and placed into PBS + 0.1% Tween (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO Cat# P-3563) for 5 min. FISH was performed on sections by co-hybridization of a custom-made N-terminal Cy3-labeled peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probe that recognizes all mammalian telomeres (N-CCCTAACCCTAACCCTAA-C) and two N-terminal FITC-labeled PNA probes (N-ATTCGTTGGAAACGGGA-C, N-CACAAAGAAGTTTCTGAG-C; Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) that recognizes both human and mouse centromeres but do not recognize rat centromeres [16]. PNA probes were applied together, each at a concentration of 300 ng/ml in diluent (70% formamide, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 0.5% B/M Blocking Reagent; Boehringer-Manheim) and slides denatured at 83°C for 4 min, followed by 2-hr hybridization at room temperature. Sections were washed twice at room temperature for 15 min with PNA wash buffer (70% formamide, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, and 0.1% BSA), followed by 3 × 5 min washes in PBS + 0.1% Tween. At this point, additional immunofluorescence staining can be conducted per the user's specifications. Immunofluorescent detection of the human luminal-secretory cell marker cytokeratins was conducted using a primary antibody cocktail containing anti-Cytokeratin 8 (BioGenex Cat# MU142-UC, diluted 1:800) and anti-cytokeratin 18 (BioGenex Cat# Am2100-11, diluted 1:1,600) incubated 45 min at room temperature, with secondary detection using anti-mouse IgG fraction Alexa Fluor 647 (Molecular Probes Cat# A21237). Nuclei were counterstained for 5 min at room temperature with a 1:10,000 dilution in water of a 5 mg/ml stock solution of DAPI (4′-6-diamidino-2-phenlindole; a DNA-binding dye; Sigma Cat# D-8417). Sections were mounted using Prolong Anti-Fade Mounting Media solution (Invitrogen). Slides were imaged with a Nikon 50i epifluorescence microscope equipped with an X-Cite series 120 illuminator and appropriate fluorescence filter sets. Gray-scale images were captured for presentation using an attached Photometrics CoolsnapEZ digital camera, pseudo-colored and merged.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining for ΔNp63 (LabVison/Neomarkers) and AR (N-20; Santa Cruz) were done as previously described [17,18]. Immunostaining for human Nkx3.1 was conducted as described previously [19].

RESULTS

Dual Labeling of Centromeres and Telomeres Using PNA FISH Allows Unambiguous Discernment Between Cells of Human, Rat, and Mouse Origin

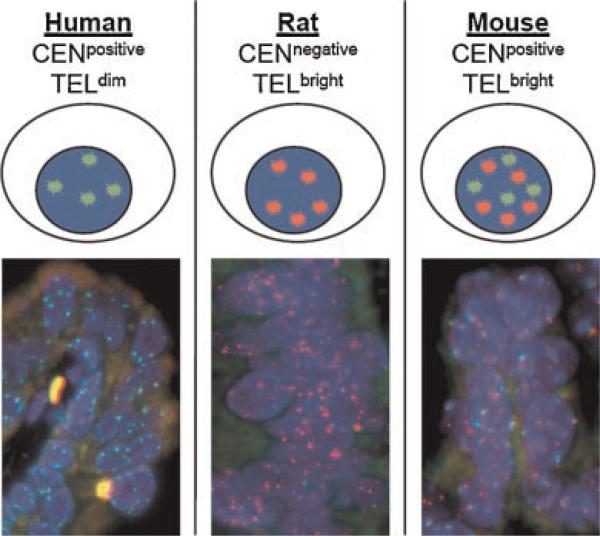

Telomeres and centromeres are composed, in part, of repeated DNA elements. In previous work we reported a rapid and simple FISH technique for staining telomeres and centromeres, featuring single cell resolution in standard archival tissue sections [20,21]. Here we exploit species-specific differences in telomeres and centromeres in order to determine a given cell's species of origin. Specifically, it has been shown that telomeres in commonly used inbred laboratory rodent strains (i.e., nude, C57BL/6J, BALB/c, DBA/2, and CBA/Ca) are significantly longer than human telomeres (50–150 kb in rodent vs. 5–10 kb in human), and this difference in length results in an easily discernable difference in the intensity of telomeric FISH signals [22]. Thus, rodent cells (mouse and rat) are easily distinguished from human cells by virtue of their very bright telomere FISH signals (Fig. 1). Importantly, this difference also holds for the majority of human cancer cells as well, since they typically possess abnormally short telomeres despite their expression of the telomere maintenance enzyme telomerase [23]. The pair of centromere-specific PNA probes utilized here hybridizes to DNA repeats in human and mouse centromeres but do not hybridize to rat centromeres (Sprague–Dawley and Copenhagen, Fig. 1) [16]. Thus, simultaneous staining with these centromere and telomere PNA FISH probes (Cen/Tel FISH) allows for rapid and unequivocal identification of species origin (human vs. rat vs. mouse) at the single cell level in tissue heterorecombinants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Depiction and representative combined centromere and telomere FISH staining on heterospecies recombinant tissues. The discernment between mouse, rat, and human cells is documented by exploiting genomic differences between the centromeres and telomeres of the three species. Inbred strains of rodents have telomeres which are 100—150 kb in length, nearly 10-fold longer than human telomeres. Thus, a Cy3-labeled telomere specific FISH probe (red colored) strongly labels rat and mouse telomeres where, at the same exposure, human telomeres are below the level of detection. Additionally, FITC-labeled centromere specific FISH probes (green colored) are used which are specific for common repeated DNA sequences between mouse and human centromeres, but do not hybridize with rat centromeres. Thus, co-staining with both probes demonstrates that human nuclei are only labeled green; rat nuclei are only labeled red; and mouse nuclei are both red and green. ADAPI co-stain aids in identifying nuclei (blue colored). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Detection of Human, Rat, and Mouse Prostatic Glandular Epithelia in Multispecies Recombinant Xenografts

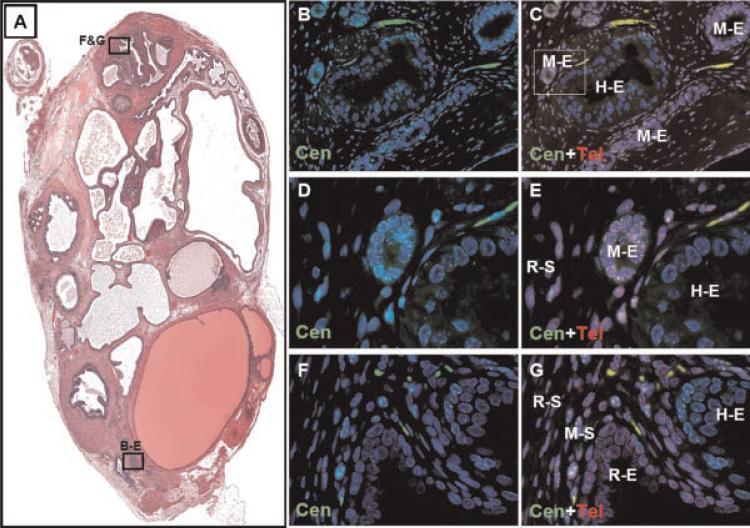

Human prostate epithelial organoids are spheres of cells isolated directly from fresh prostate tissue via collagenase digestion and density sedimentation [10,24]. Such organoids contain all the components of the prostate epithelial compartment, including stem, basal, luminal, and neuroendocrine cells. Previous reports have shown that such organoids are capable of forming prostatic glandular structures in vivo with and without the presence of rodent UGSM [10,24]. For the purpose of testing the contribution of rat, mouse, and human cells to prostate heterorecombinants, and to test the utility of Cen/Tel FISH staining, we recombined human prostate epithelial organoids with Sprague–Dawley rat UGSM which were implanted under the renal capsule of male nude mice. After 3 months the grafts were removed and analyzed for the contribution of human, rat, and mouse cells. Significantly, Cen/Tel FISH staining documented that all three species contributed to the glandular structures observed, and all three types of glands were morphologically similar (Fig. 2). Such staining documented the presence of glands of human origin intermixed and even fusing with glandular structures of both rat and mouse origin (Fig. 2B–G). Analysis of the stroma documented that the vast majority of stromal cells are rat, which were derived from the rat UGSM (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

A heterorecombinant derived from human prostate epithelial organoids combined with rat UGSM and implanted within a host nude mouse contains glandular structures derived from human, rat, and mouse. A: H&E stain of heterospecies recombinant after 3 months of growth. Multiple glands were observed, and serial sections were subjected to combined centromere and telomere FISH. The boxed regions correspond to the images displayed in parts B–G. B: Centromere FISH (green) documenting the presence of Cen+ glandular structures surrounded by predominately Cen-negative stroma (20×). C: Combined centromere and telomere FISH documenting the presence of both mouse and human epithelial glands with stroma consisting mostly of rat cells (M-E, mouse epithelia; H-E, human epithelia; 20×).The box represents images displayed in D and E. D: Centromere FISH documenting Cen+ glands (40×). E: Combined centromere and telomere FISH documenting the presence of both mouse and human epithelial glands with stroma consisting of rat cells (R-S, rat stroma, 40×). F: Centromere FISH documenting glands which are both Cen+ and Cen-negative, surrounded by Cen+ and Cen-negative stroma (20×). G: Combined FISH staining documenting human and rat glands (R-E, rat epithelia; H-E, human epithelia) surrounded by a stroma containing rat and mouse cells (R-S, rat stroma; M-S, mouse stroma; 20×). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

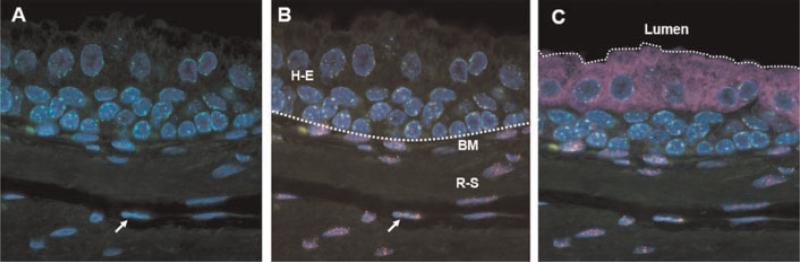

Fig. 3.

Quadruple labeling of glandular structures in tissue heterorecombinants. Centromere/telomere staining was combined with immuno-fluorescent staining for luminal cytokeratins and co-stained with DAPI. A: Centromere FISH (green) documenting Cen+ glandular structure surrounded by a Cen-negative rat stroma. DAPI co-staining marks cellular nuclei (blue).B: Combined centromere/telomere FISH (green and red) illustrating human glandular epithelia (H-E) next to a rat stroma (R-S). The arrow depicts a cell of mouse origin within the stroma. The dotted line depicts the basement membrane (BM) dividing the epithelial and stromal compartment. C: Additional immunofluorescent stain for luminal epithelial cytokeratins (purple), marking the edge of the glandular lumen (dotted line). [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

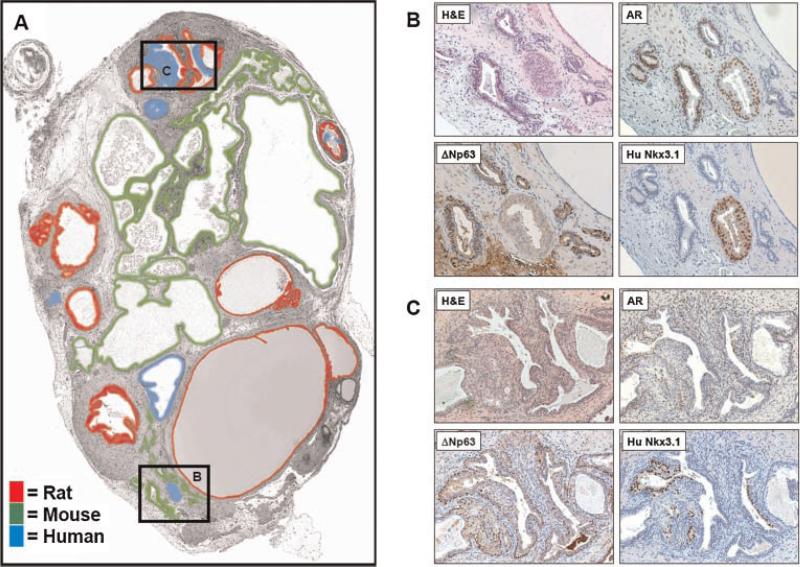

Glandular Epithelia Derived From Human, Rat, and Mouse Exhibit Characteristics of Prostate Tissue

Immunohistochemical staining of the tissue recombinants revealed that glandular structures derived from all three species, human, mouse and rat, contain ΔNp63+ basal cells and AR+ luminal-secretory cells (Fig. 4B,C). Glands derived from human cells also stained positive for Nkx3.1 using a human-specific antibody (Fig. 4B,C). In addition to Cen/Tel FISH, the use of a human-specific Nkx3.1 antibody was able to accurately identify human-derived, AR+ prostate luminal epithelial cells (Fig. 4B,C) [19]. In one instance, Cen/Tel FISH documented the fusion of both rat and human glands, and the human-specific Nkx3.1 antibody was able to distinguish between rat and human luminal cells (Fig. 4C). Importantly, we document the presence of mouse-derived glands which are characteristically prostate, containing ΔNp63+ and AR+ populations (Fig. 4B). Thus, combined centromere and telomere FISH allowed discrimination of species of origin, providing clear identification of human, mouse, and rat-derived cells. Importantly, heterospecific recombinants using human prostate epithelial cells plus rat UGSM implanted under the renal capsule of an immunocompromised mouse displayed a complex glandular and immunohistochemical staining pattern revealing epithelial structures derived from each of the three species. These results highlight the importance of such a technique, whereby rodent glands could be potentially misinterpreted to be of human origin.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical analyses of species-mapped heterorecombinant. Serial sections were stained for markers characteristic of prostate epithelia. A: Color-codedspeciesmap of the epithelial glandular structures observed in the multispecies recombinant as determined by combined telomere + centromere FISH. Surprisingly, much of the epithelium was of mouse origin. The boxed regions correspond to the images displayed in parts B and C. B: Staining of a region where a human gland was surrounding by mouse glands. Upper left panel: H&E stain. Upper right panel: Androgen receptor staining illustrating that both mouse and human glands express luminal AR. Lower left panel: Basal cell ΔNp63 staining in the mouse glands. Lower right panel: Specific staining of the human luminal cells using a human-specific anti-Nkx3.1 antibody. C: Staining of a regionof fused rat and human glands. Upper left panel: H&E stain. Upper right panel: Androgen Receptor staining illustrating that both rat and human glands express luminal AR. Lower left panel: Basal ΔNp63 staining in the rat glands. Lower right panel: Specific staining of the human luminal cells using a human-specific anti-Nkx3.1 antibody. [Color figure canbeviewedin the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

DISCUSSION

There is a rapidly growing interest in utilizing the inductive potential of rodent UGSM for tissue recombination and stem cell approaches. Such an experimental system holds great promise towards aiding our understanding of normal prostate function and carcinogenesis. However, tissue heterorecombinants containing cells from multiple species also has the potential to lead to data misinterpretation. Here we document the presence of host mouse glandular structures within a rat–human heterorecombinant. Regions of human glands were presumably from the epithelial organoids; regions of rat glands were presumably from unsuspected contaminating rat UGSE cells; and regions of host mouse glands were either from circulating pluripotent stem cells or local epithelial cells which were induced to form glandular appearing structures by the implant. As a consequence, additional steps to ensure the cell type of origin, such as the combined centromere and telomere FISH, should become a standard staining protocol when working with such recombinants.

Human tissue xenografting into immunocompromised mouse strains provides a powerful tool for the observation and manipulation of human cells and tissues in vivo. Cancer researchers have long used human tumor xenografts in mice to study basic aspects of tumor biology and for testing experimental therapeutics. More recently, stem cell biologists and tissue technologists use immunocompromised rodent hosts as a medium for the study of stem cell biology, tissue maintenance and turnover, angiogenesis, and epithelial to mesenchyme transitions (EMT). Of critical importance to such xenografting studies is the ability to discern the cellular contribution of rodent cells to the developing human implant. Typically, stromal and immune cells of the rodent host infiltrate and interact with the human tissue implant, and at the experimental endpoint the xenograft consists of an admixed assortment of rodent and human cells. Numerous methods have been developed to aid in distinguishing rodent cells from human cells, including differences in nuclear morphology; detection of species-specific epitopes by immunohistochemistry pre-labeling cells with a stable marker such as GFP; or in situ hybridization to species-specific nucleotide sequences [25–30]. Such methods have a series of shortcomings. First, they often fail to distinguish between mouse and rat tissue. Second, pre-labeling of cells using viral infections is often impossible or may have negative or unpredictable affects on cell viability and behavior. Third, immunostaining with antibodies is limited to specific tissues and established markers, and mouse monoclonal antibodies are prone to generate spurious positive signals due to endogenous mouse antibodies which react with secondary detection reagents. Likewise, host cross-reactivity with certain antibodies frequently occurs. Finally, many in situ protocols do not allow for simultaneous immunohistological or immunofluorescent analysis and thus require step sectioning and staining of adjacent tissue sections.

The combined centromere and telomere PNA FISH represents a simple, rapid, robust, and unambiguous method for identifying the species of origin for cells and tissue structures resulting from human and/or rat xenografts and tissue recombinants grown in immunocompromised mice. Such a method provides significant advantages over currently available methods to discriminate between human and rodent cells. First, this method is applicable to standard formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissue sections and additionally allows for simultaneous immunofluorescence analysis of protein epitopes, as shown here as well as previously [20]. Second, in contrast to immunohistochemistry, where antibody specificity may limit the types of cells or tissues evaluable, PNA FISH can be employed on any cell or tissue type. Third, it clearly distinguishes between mouse and rat cells as well as human cells. Fourth, it circumvents problems associated with cross-species antibody reactivity, as well as cross reactions between secondary detection reagents used for mouse monoclonal primary antibodies and endogenous mouse immunoglobulins. Fifth, no pre-labeling of the implanted cells is required for detection. Sixth, the PNA probes are more stable than standard DNA probes. Finally, the technique is simple enough to be used by investigators not trained in histology. In the growing era of xenotransplantation, stem cell biology, and tumor biology, the use of such a method has the potential to become an indispensable tool to analyze xenograft/host interactions and prevent misinterpretation of data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the expert assistance of Jessica Hicks of the Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology for the immunostaining and for Dr. Charles Beiberich of the University of Maryland Baltimore County for the anti-human Nkx3.1 antibody. Donald Vander Griend was supported by a Urology Training Grant, NIH T32DK07552 and is now supported by a DOD Post-Doctoral Training Award, PC060843. JTI is generously funded from NIH Grant R01DK52645 and the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund MSCRFII-0428-00. AKM and YK are generously funded by a DOD award (W81XWH-06-1-0052) and the Patrick C. Walsh Prostate Cancer Research Fund.

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant numbers: T32DK07552, R01DK52645; Grant sponsor: Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund; Grant number: MSCRFII-0428-00; Grant sponsor: Patrick C. Walsh Prostate Cancer Research Fund; Grant sponsor: Department of Defense Post-Doctoral Training Award; Grant number: PC060843.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cunha GR, Chung LW. Stromal-epithelial interactions—I. Induction of prostatic phenotype in urothelium of testicular feminized (Tfm/y) mice. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14(12):1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunha GR, Sekkingstad M, Meloy BA. Heterospecific induction of prostatic development in tissue recombinants prepared with mouse, rat, rabbit and human tissues. Differentiation. 1983;24(2):174–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1983.tb01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunha GR, Alarid ET, Turner T, Donjacour AA, Boutin EL, Foster BA. Normal and abnormal development of the male urogenital tract. Role of androgens, mesenchymal-epithelial interactions, and growth factors. J Androl. 1992;13(6):465–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunha GR, Foster B, Thomson A, Sugimura Y, Tanji N, Tsuji M, Terada N, Finch PW, Donjacour AA. Growth factors as mediators of androgen action during the development of the male urogenital tract. World J Urol. 1995;13(5):264–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00185969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboseif S, El-Sakka A, Young P, Cunha G. Mesenchymal reprogramming of adult human epithelial differentiation. Differentiation. 1999;65(2):113–118. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1999.6520113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Revelo MP, Sudilovsky D, Cao M, Chen WG, Goetz L, Xue H, Sadar M, Shappell SB, Cunha GR, Hayward SW. Development and characterization of efficient xenograft models for benign and malignant human prostate tissue. Prostate. 2005;64(2):149–159. doi: 10.1002/pros.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor RA, Cowin PA, Cunha GR, Pera M, Trounson AO, Pedersen J, Risbridger GP. Formation of human prostate tissue from embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3(3):179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vander Griend DJ, Karthaus WK, Dalrymple S, Meeker AK, De Marzo AM, Isaacs JT. The role of CD133 in normal human prostate stem cells and malignant cancer initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9703–9711. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staack A, Donjacour AA, Brody J, Cunha GR, Carroll P. Mouse urogenital development: A practical approach. Differentiation. 2003;71(7):402–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2003.7107004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao J, Arnold JT, Isaacs JT. Conversion from a paracrine to an autocrine mechanism of androgen-stimulated growth during malignant transformation of prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(13):5038–5044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunha GR, Donjacour A. Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions: Technical considerations. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1987;239:273–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xin L, Ide H, Kim Y, Dubey P, Witte ON. In vivo regeneration of murine prostate from dissociated cell populations of postnatal epithelia and urogenital sinus mesenchyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11896–11903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734139100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung LW, Cunha GR. Stromal-epithelial interactions: II. Regulation of prostatic growth by embryonic urogenital sinus mesenchyme. Prostate. 1983;4(5):503–511. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990040509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Sudilovsky D, Zhang B, Haughney PC, Rosen MA, Wu DS, Cunha TJ, Dahiya R, Cunha GR, Hayward SW. A human prostatic epithelial model of hormonal carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61(16):6064–6072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meeker AK, Hicks JL, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Montgomery EA, Westra WH, Chan TY, Ronnett BM, De Marzo AM. Telomere length abnormalities occur early in the initiation of epithelial carcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3317–3326. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0984-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Hong YK, Ontiveros SD, Egholm M, Strauss WM. Single base discrimination of CENP-B repeats on mouse and human Chromosomes with PNA-FISH. Mamm Genome. 1999;10(1):13–18. doi: 10.1007/s003359900934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litvinov IV, Vander Griend DJ, Xu Y, Antony L, Dalrymple SL, Isaacs JT. Low-calcium serum-free defined medium selects for growth of normal prostatic epithelial stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(17):8598–8607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litvinov IV, Vander Griend DJ, Antony L, Dalrymple S, De Marzo AM, Drake CG, Isaacs JT. Androgen receptor as a licensing factor for DNA replication in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(41):15085–15090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603057103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bethel CR, Faith D, Li X, Guan B, Hicks JL, Lan F, Jenkins RB, Bieberich CJ, De Marzo AM. Decreased NKX3.1 protein expression in focal prostatic atrophy, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, and adenocarcinoma: Association with Gleason score and chromosome 8p deletion. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):10683– 10690. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meeker AK, Gage WR, Hicks JL, Simon I, Coffman JR, Platz EA, March GE, De Marzo AM. Telomere length assessment in human archival tissues: Combined telomere fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(4):1259–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62553-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meeker AK, Hicks JL, Platz EA, March GE, Bennett CJ, Delannoy MJ, De Marzo AM. Telomere shortening is an early somatic DNA alteration in human prostate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62(22):6405–6409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kipling D, Cooke HJ. Hypervariable ultra-long telomeres in mice. Nature. 1990;347(6291):400–402. doi: 10.1038/347400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of lifespan by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells. Science. 1998;279(5349):349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayward SW, Haughney PC, Rosen MA, Greulich KM, Weier HU, Dahiya R, Cunha GR. Interactions between adult human prostatic epithelium and rat urogenital sinus mesenchyme in a tissue recombination model. Differentiation. 1998;63(3):131–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1998.6330131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunha GR, Vanderslice KD. Identification in histological sections of species origin of cells from mouse, rat and human. Stain Technol. 1984;59(1):7–12. doi: 10.3109/10520298409113823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehr HA, Skelly M, Buhler K, Anderson B, Delisser HM, Gown AM. Microvascular endothelium of human tumor xenografts expresses mouse (=host) CD31. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1997;17(3):138–142. doi: 10.1159/000179221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graem N, Dabelsteen E. Species identification of epidermal cells in the human skin/nude mouse model with lectins. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [A] 1984;92(5):317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1984.tb04410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao J, Tombal B, Isaacs JT. Rapid in situ hybridization technique for detecting malignant mouse cell contamination in human xenograft tissue from nude mice and in vitro cultures from such xenografts. Prostate. 1999;39(1):67–70. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990401)39:1<67::aid-pros11>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obara T, Conti CJ, Baba M, Resau JH, Trifillis AL, Trump BF, Klein-Szanto AJ. Rapid detection of xenotransplanted human tissues using in situ hybridization. Am J Pathol. 1986;122(3):386–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chubinskaya S, Jacquet R, Isogai N, Asamura S, Landis WJ. Characterization of the cellular origin of a tissue-engineered human phalanx model by in situ hybridization. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(7–8):1204–1213. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]