To the Editor

Thousands of patients undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) annually worldwide for treatment of hematologic malignancies as well as benign hematologic and immune disorders. We and others have previously shown that despite severe thrombocytopenia and a high incidence of bleeding complications, 3.7–4.5 % of patients undergoing HSCT suffer symptomatic venous thromboembolism (VTE) [1–5]. Despite the relatively common occurrence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), the optimal approach to VTE prophylaxis for patients undergoing HSCT remains undefined. The absence of high-quality evidence, the narrow risk–benefit ratio, and the lack of published guidelines have all contributed to a therapeutic equipoise regarding the utility of VTE prophylaxis in this setting. As a result, we expected that practice patterns would vary significantly at the physician, institution, and country levels. To determine the current spectrum of VTE prevention practices among physicians caring for patients hospitalized for HSCT, we conducted an anonymous web-based survey of members of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT).

Based on our anecdotal experience, we hypothesized that there would be considerable practice variation among providers and that many providers would use ambulation alone or mechanical VTE prophylaxis in their hospitalized patients undergoing HSCT. To test these hypotheses, we generated a web-based survey to determine institutional VTE prevention practices. The survey questions assessed respondent demographics, institutional affiliation, the number and characteristics of HSCT performed annually, and current VTE prevention practices. We created the survey using the SurveyMonkey software (SurveyMonkey.com LLC., Palo Alto, CA). The survey was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board and ASBMT. The link to the survey along with an introductory letter were distributed via email by the ASBMT to its members on 6/27/2012 with two subsequent reminders sent at 2-week intervals. Respondents were allowed to complete the survey only once. To increase the response rate, we offered respondents who completed the survey a chance to win a 200-dollar gift certificate. Data from survey was de-identified and stored on a password-protected computer. The survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

A total of 114 providers from 18 countries practicing in 95 different institutions completed the survey. Responses were received between 6/27/2012 and 8/15/2012. The majority of responders were from the United States of America (USA) (69 %); but responses were received from Canada (six responders); Australia (five responders); Mexico, Spain, Germany (three responders each); India, Saudi Arabia, New Zealand (two responders each); and Oman, Thailand, China, Turkey, UK, Egypt, Singapore, Chile, and Croatia (one responder each). The median age of responders was 47 years (standard deviation, 10.3 years). Characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of survey responders

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Country of Practice | |

| USA-based | 79 (69 %) |

| Non USA-based | 35 (31 %) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 82 (72 %) |

| Female | 32 (28 %) |

| Age (median in years, ±standard deviation) | 47 ± 10.3 |

| Board-certification | |

| Hematology | 25 (22 %) |

| Medical oncology | 13 (11 %) |

| Hematology/oncology | 39 (34 %) |

| Pediatric hematology/oncology | 27 (24 %) |

| Other | 10 (9 %) |

| Job description | |

| Clinical researcher | 52 (46 %) |

| Clinician | 47 (41 %) |

| Clinical educator | 7 (6 %) |

| Basic science researcher | 3 (3 %) |

| other | 5 (4 %) |

| Number of years post-fellowship training | |

| 0–5 years | 25 (22 %) |

| 6–10 years | 22 (19 %) |

| 11–20 years | 29 (25 %) |

| 21 or more years | 38 (33 %) |

| Type of institution of Practice | |

| University affiliated/Public | 91 (80 %) |

| Private | 22 (19 %) |

| Military | 1 (1 %) |

| Number of HSCT performed at the institution per year | |

| 100 or less | 62 (54 %) |

| 101–250 | 30 (26 %) |

| More than 250 | 22 (19 %) |

| Institution’s approach for documentation | |

| Paper medical records only | 7 (6 %) |

| Electronic medical records only | 46 (40 %) |

| Mixture of electronic and paper medical records (or in transition) | 61 (54 %) |

| Institution’s approach for provider order | |

| Paper order entry only | 25 (22 %) |

| Electronic order entry | 45 (40 %) |

| Mixture of electronic and paper order entry (or in transition) | 44 (39 %) |

| Is there a cancer-specific VTE prophylaxis order set at your institution? | |

| Yes | 37 (33 %) |

| No | 65 (57 %) |

| Not sure | 12 (11 %) |

| Is there a HSCT-specific VTE prophylaxis order set at your institution? | |

| Yes | 16 (14 %) |

| No | 95 (83 %) |

| Not sure | 3 (3 %) |

VTE venous thromboembolism, HSCT hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

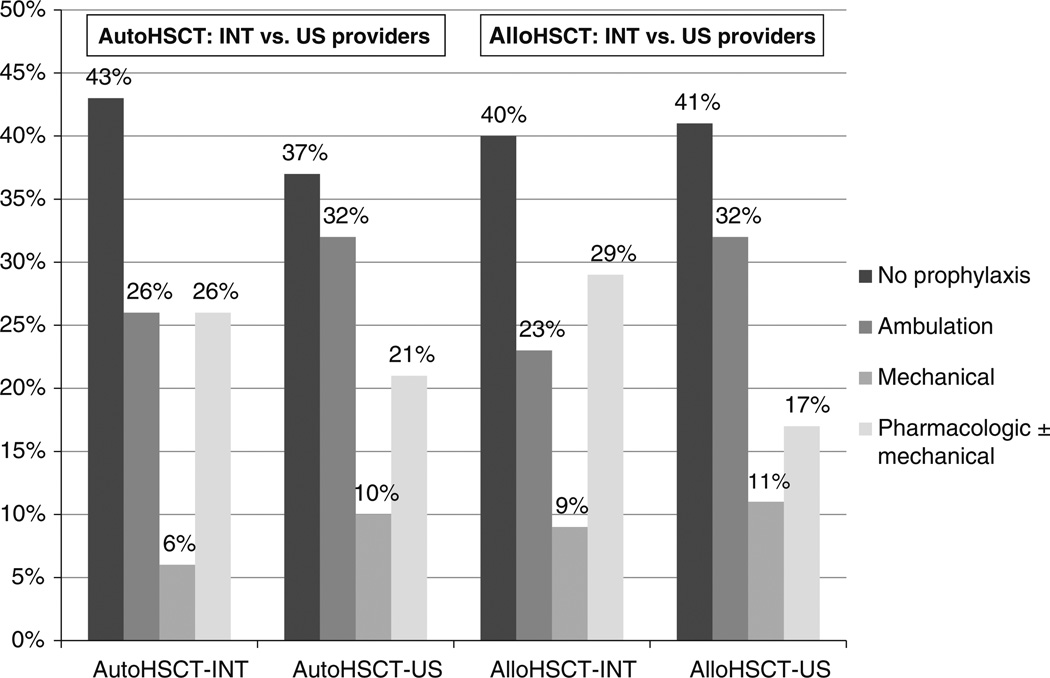

As shown in Fig. 1, no prophylaxis was the most common approach to VTE prevention reported by providers for both allogeneic and autologous HSCT patients (41 vs 39 %). Ambulation only (29 vs 30 %), pharmacological prophylaxis ± mechanical prophylaxis (20 vs 22 %) and mechanical prophylaxis alone (10 vs 9 %) were used less frequently for both HSCT populations. Unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin were used in 1 % and 13 %, respectively, while 7 % prescribed a combination of mechanical and pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. A similar approach to VTE prevention was used in patients undergoing autologous HSCT. 16 % used LMWH, while 7 % prescribed a combination of mechanical and pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. One respondent reported using fondaparinux and 2 others reported using continuous intravenous low dose heparin infusion for VTE prophylaxis. Overall, there were no significant differences between the USA and international respondents in their approaches to VTE prophylaxis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Practice patterns of VTE prophylaxis for patients hospitalized for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for 114 international providers. Allo Allogeneic Auto Autologous US United States INT International

Most providers who would use a pharmacologic anticoagulant for VTE prophylaxis indicated that the platelet count threshold below which they would withhold the anticoagulant is 50,000/lL (79 %). Fewer providers referred to 30,000/lL (19 %) or 75,000/lL (2%) as a platelet count threshold for withholding pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. 30 % of respondents cited a perceived low risk of VTE as the most important reason for their current approach to VTE prophylaxis, while 24 % cited the high risk of bleeding and 24 % the absence of data supporting VTE prophylaxis in this setting. 17 % cited their institutional policy as the most important reason for their current VTE prevention practice in HSCT patients. Overall, the international thromboprophylaxis practice patterns seemed consistent with the American patterns, but we could not make further conclusions due to the small number of international responses distributed over many individual countries.

This is the first reported international survey to determine the spectrum of approaches to VTE prophylaxis used by health care professionals who care for patients hospitalized for HSCT. Our results indicate considerable heterogeneity in clinical practice. The utilization rates of pharmacologic and mechanical methods of VTE prophylaxis were generally low, especially for pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. Only about 15 % of providers prescribed pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. Despite differences in VTE incidence reported in some studies [1–5], we did not note any differences in the approach to VTE prophylaxis for patients undergoing allogeneic and autologous HSCT. Most providers cited a high perceived risk of bleeding, a relatively lower risk of VTE, a lack of efficacy data, and institutional policies as the basis for their practices.

Like any survey analysis, our results are subject to selection bias and depend on the accuracy of data reported by respondents. In addition, our results only pertain to patients hospitalized for HSCT. Due to the modest response rate, we were unable to perform a detailed analysis of practice differences between US practitioners and physicians from other countries. Lastly, we have not assessed the effect of the type of the underlying malignancy or the condition of the patient on the provider’s decision or the institutional policy of using thromboprophylaxis. Nevertheless, our data clearly demonstrate that there is a need for further investigation to identify the most effective approach to VTE prophylaxis in this vulnerable population.

Acknowlegments

Michael Streiff has received research funding from Sanofi-Aventis and Bristol Myers Squibb, honoraria for CME lectures from Sanofi-Aventis and Ortho-McNeil, consulted for Sanofi-Aventis, Eisai, Daiichi-Sankyo, Boehringer-Ingelheim and Janssen HealthCare and has given expert witness testimony in various medical malpractice cases. This research was funded in part by grant P01CA15396 from the National Cancer Institute (JBM co-investigator). Javier Bolaños-Meade is an Investigator-2, Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (CONACYT, Mexico).

Footnotes

This study was presented in part at the 54th Annual American Society of Hematology meeting in Atlanta, GA, December, 2012.

Contributor Information

Amer M. Zeidan, Department of Oncology, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

Jessica Wellman, Department of Pharmacy, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Patrick M. Forde, Department of Oncology, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Javier Bolaños-Meade, Department of Oncology, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Michael B. Streiff, Email: mstreif@jhmi.edu, Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA.

References

- 1.Gerber DE, Segal JB, Levy MY, Kane J, Jones RJ, Streiff MB. The incidence of and risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and bleeding among 1,514 patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: implications for VTE prevention. Blood. 2008;112:504–510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonsalves A, Carrier M, Wells PS, McDiarmid SA, Huebsch LB, Allan DS. Incidence of symptomatic venous thromboembolism following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1468–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pihusch R, Salat C, Schmidt E, Göhring P, Pihusch M, Hiller E, Holler E, Kolb HJ. Hemostatic complications in bone marrow transplantation: a retrospective analysis of 447 patients. Transplantation. 2002;74:1303–1309. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200211150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsakiris DA, Tichelli A. Thrombotic complications after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: early and late effects. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2009;22:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falanga A, Marchetti M. Venous thromboembolism in the hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4848–4857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]