Abstract

Ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes have emerged both as promising probes of DNA structure and as anticancer agents because of their unique photophysical and cytotoxic properties. A key consideration in the administration of those therapeutic agents is the optimization of their chemical reactivities to allow facile attack on the target sites, yet avoid unwanted side effects. Here, we present a drug delivery platform technology, obtained by grafting the surface of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) with ruthenium(II) dipyridophenazine (dppz) complexes. This hybrid nanomaterial displays enhanced luminescent properties relative to that of the ruthenium(II) dppz complex in a homogeneous phase. Since the coordination between the ruthenium(II) complex and a monodentate ligand linked covalently to the nanoparticles can be cleaved under irradiation with visible light, the ruthenium complex can be released from the surface of the nanoparticles by selective substitution of this ligand with a water molecule. Indeed, the modified MSNPs undergo rapid cellular uptake, and after activation with light, the release of an aqua ruthenium(II) complex is observed. We have delivered, in combination, the ruthenium(II) complex and paclitaxel, loaded in the mesoporous structure, to breast cancer cells. This hybrid material represents a promising candidate as one of the so-called theranostic agents that possess both diagnostic and therapeutic functions.

INTRODUCTION

The photochemical activation of drugs1 is expected to have a significant impact in many fields of medicine including oncology. The use of light, which notably has led2 to the clinical development of photodynamic therapy (PDT) for the treatment of cancer and other diseases, offers the possibility to control the location, timing, and dosage of therapeutic compounds. An increased understanding of cancer at the molecular level has enabled the development of novel therapeutic agents that are sometimes referred to3 as molecular targeted agents. Unlike the drugs used in conventional chemotherapy, these agents are designed to interfere specifically with key molecular events that are responsible for the malignant phenotype: they hold considerable promise for extending the therapeutic window and providing more effective treatment options when compared to traditional cytotoxic therapies.

In this context, transition metal complexes with DNA cleavage activities have attracted4 much attention because of their uses as DNA structure probes and as anticancer agents. Since the discovery5 that octahedral metal complexes with a dppz ligand (dppz = dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) function as molecular “light switches” for DNA upon metal-to-ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) excitation, there has been much attention devoted6 to the biological activity of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes, in particular in relation to the development7 of structure-specific DNA probes in living cells. On account of their unique photophysical responses to DNA, dppz complexes of ruthenium have been investigated8 widely and different modes of interactions of those complexes with DNA, via intercalation5,8a of the ligand or through direct covalent coordination6 of the electron rich DNA bases with the metal center, have been revealed. Recently, the distinctive modes of intercalation of the DNA light-switching complex [Ru(phen)2(dppz)]2+ (phen = 1,10-phenanthroline) have been elucidated9 from crystal structures. Besides binding to well-matched DNA, Barton and co-workers10 have discovered that the complex [Ru(bipy)2(dppz)]2+ (bipy = 2,2′-bipyridine) shows enhanced luminescence in the presence of DNA defects, such as base mismatches, leading these researchers to envisage their use as a direct detection method for the mismatch repair deficiency in biological samples.

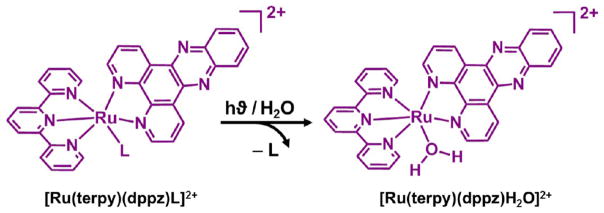

Ruthenium(II) complexes are therefore poised to become invaluable therapeutic tools, since they also possess tunable photophysical properties. Although complexes of the [Ru(bipy)3]2+ family are generally considered to be photochemically stable,11 structural modifications of the parent trisbipyridine complex have been shown to afford compounds undergoing clean photoexpulsion of a given ligand12 with a high quantum efficiency. Recently, Glazer and co-workers13 synthesized a series of Ru(diimine)32+ complexes and tested their cytotoxity upon visible light irradiation in lung cancer and leukemia cells. These complexes are inert in the dark but react rapidly upon photoexcitation with visible light to eject a ligand and cross-link DNA, providing even greater cytotoxicity than cisplatin. Complexes of the [Ru(terpy)(N–N)L]2+ (terpy = 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine and N–N is the bidentate chelate) family are equally promising, since the distortion of the coordination octahedron is sufficient to decrease14 the ligand field state significantly. Indeed, the relatively poor ligand field of the terpy ligand leads to photolabile complexes with the clean expulsion (Figure 1) of the monodentate ligand L on irradiation with light. Many examples14,15 of such photochemically labile ruthenium(II) complexes containing the terpy ligand have been described in the past few years. Quite recently, related complexes have been used in conjunction with biologically active compounds15 or vesicles16 to trigger the interaction of ruthenium(II) complexes with large supramolecular structures using a photonic signal.

Figure 1.

Photochemical activation of ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complex. The monodentate ligand (L) is photoexpelled from the ruthenium(II)–dppz complex on irradiation with visible light.

The virtues of biomolecular targeting and cellular delivery have been extolled in recent years, and if progress continues apace, then it is possible that ruthenium(II) complexes may find a wide range of future biomedical and therapeutic applications. The challenges associated with the administration of these therapeutic agents include, among others, the ability to control drug exposure temporally to the target of interest, an objective that is difficult to achieve when drugs are administered individually. Here, we present a drug delivery platform technology that uses light as the remote means of triggering biologically active ruthenium complexes. The progress made so far in the realm of nanotechnology to develop approaches for the effective delivery of drugs in a temporally regulated manner to cancer cells, along with the incorporation of chemotherapeutic agents into nanoparticle-based delivery devices,17 holds significant promise. In particular, programmable drug delivery systems would allow3,18 repeated on-demand dosing that would be adaptable to the patients’ regimen and allow multiple dosages from a single administration, a strategy that would also address the potential importance of timing on the therapeutic effect in the treatment of cancer.19

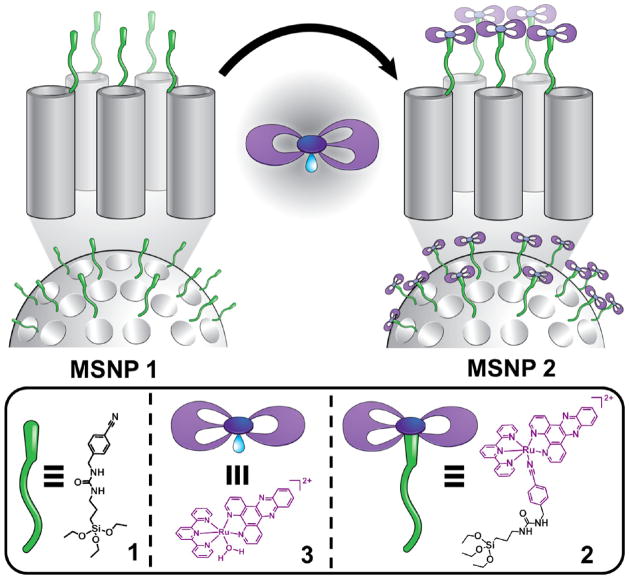

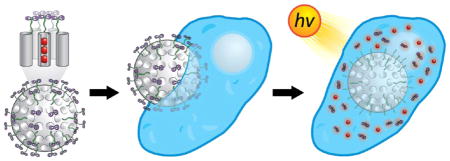

Since they are nontoxic to cells and can undergo cellular uptake into acidic liposomes by endocytosis, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) have emerged recently as a promising drug delivery system.20 Silica nanoparticles with good biocompatibility are an ideal platform for biomedical applications21 because they have robust and well-defined structures for functionalization with multiple labels, targeting or therapeutic agents,22 and the ability to release a drug under specific conditions such as pH changes,23 photonic signals,24 redox activation,25 or biological triggers.26,27 The present work is a proof-of-concept demonstration of such a platform technology involving the marriage of an octahedral ruthenium(II) complex and inorganic nanoparticles, namely, MSNPs. Herein, we report the ligand photosubstitution reactions of a ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complex at the water–MSNP interface. The hybrid material obtained by the coordination of the ruthenium(II) complex onto the MSNPs surface, grafted with a monodentate ligand, exhibits (Figure 2) unique photophysical properties in comparison with the ruthenium(II) complex in solution. The luminescence of the surface-grafted complex is enhanced significantly with respect to the free complex in solution as a result of the shielding of the phenazine nitrogen atoms of the dppz ligand by water. Under irradiation with visible light the surface-grafted complex leads to the selective substitution of the monodentate ligand by a water molecule, thus releasing the aqua complex 3, i.e., [Ru(terpy)-(dppz)(H2O)]2+, which is not emissive in aqueous solution. The subsequent binding to DNA is accompanied by emission enhancement of the complex, ideal for applications in cellular imaging. We have developed mechanized nanoparticles for the release of fluorescent and cytotoxic cargos from the MSNPs pores, capped with the ruthenium(II) complexes. Indeed, the modified MSNPs, loaded with cytotoxic cargo, undergo rapid cellular uptake, and an improved therapeutic index is observed with light activation in cancer cells. Because of its facile preparation, stability, and emission properties, this photoactive drug delivery system provides a potential route to use this multifunctional agent as a dual luminescence imaging and therapeutic nanomedicine.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation for the assembly of mechanized nanoparticles (top) and the structural formula of the ruthenium–dppz complex (bottom). The ligand 1 is grafted onto the surface of MCM-41 with an average nanopore diameter of 2 nm, followed by coordination of the aqua ruthenium(II) complex 3 under dark conditions at room temperature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design and Synthesis of Nanoparticles

The grafting of MSNPs with the ruthenium(II) complexes starts with the bare MCM-41 nanoparticles which are first of all functionalized with compound 1 containing (i) the nitrile function able to interact with the metal center and (ii) the anchoring unit for the nanoparticles, the synthesis of which is achieved by coupling 3-isocyanatopropylethoxysilane with 4-(aminomethyl)-benzonitrile (see Supporting Information for experimental details). The synthetic strategy employed for the preparation of MCM-41, based on a well-established23b surfactant-directed self-assembly procedure, ensures that the ligand molecules are located only and specifically at the exposed areas, namely, around the orifices of the nanopores on the surface of the nanoparticles. The benzonitrile-functionalized MSNPs 1 were characterized by FT-IR and 13C and 29Si cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CP-MAS) solid-state NMR spectroscopy. The 29Si CP-MAS solid-state NMR spectrum shows distinct resonances at around −100 ppm for the siloxane and −60 ppm for the organosiloxane (Figure S8 in Supporting Information), thus providing direct evidence of the grafting of 1 on the surface of the nanoparticles. Examination of the 13C CP-MAS solid-state NMR spectrum of MSNPs 1 shows the resonances typical of the ligand (Figure S9). The FT-IR spectrum of the MSNPs 1 shows a peak at 2225 cm−1, indicating the presence of C≡N bonds (Figure S13).

Coordination of the monodentate ligand on MSNPs 1 to ruthenium(II) complexes was realized (Figure 2) by a heterogeneous reaction of MSNPs 1 with the aqua complex 3 in Me2CO under low light conditions at room temperature (see Supporting Information for experimental details). The fact that the replacement of the coordinating H2O molecule in the complex [Ru(terpy)(dppz)(H2O)]2+ with the nitrile ligand on the MSNPs 1 takes place selectively and quantitatively at room temperature was first established in solution (Figures S5–S7). In particular, we found the ruthenium complex 2 to be thermally inert, while benzonitrile is a good unidentate leaving group under light irradiation. After a 1-day reaction, MSNPs 2 were isolated and characterized by FT-IR, XPS, and 13C CP-MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopies (Figures S10–S12, S14), demonstrating that the proposed procedure for the preparation of the MSNPs modified with the ruthenium(II) complex was successful. Importantly, upon coordination of the complex with the ligand on MSNPs surface, the intensity of the IR band for the stretching of C≡N bond decreases significantly. It appears that when the nanoparticles are grafted with the ruthenium(II) complex, the ordered mesostructures of the nanoparticles experience no apparent changes, as judged by XRD (Figure S15), indicating that MSNPs 2 retain the characteristics of MCM-41.

In all cases, TEM analyses demonstrate that both the ordered mesoporous structure and the nanoparticle morphology were retained after modification (Figure S16). Nitrogen adsorption/desorption measurements of the hybrid materials, before and after the coordination on the MSNPs surface, revealed that the ruthenium complex is successful in capping the mesopores (Figure S17).

Spectroscopic Properties

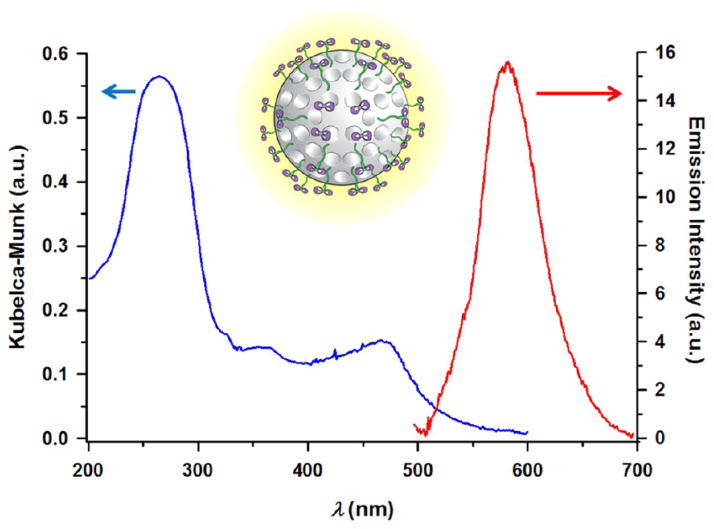

The characteristic adsorption bands of the ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complex were observed (Figure 3) for the MSNPs 2 by diffuse reflectance (DR) UV–vis spectroscopy. The reflectance spectra were elaborated by using the Kubelka–Munk function. The spectrum of MSNPs 2 showed characteristic π–π* intraligand transitions centered on 270 nm, while the MLCT transitions of the Ru(II) centers were observed at 450 nm. This MLCT band is strongly dependent on the nature of the unidentate ligand, and as the coverage of the ruthenium complex on the surface increases, no significant difference in the position of the absorption maxima is observed with respect to the spectrum of 2 in solution (Figure S18). Quite unexpectedly, excitation into the MLCT adsorption band of an aqueous suspension of MSNPs 2 gives rise (Figure 3) to an MLCT-centered emission at 585 nm. An emission quantum yield ϕem of ~0.018 was measured for MSNPs 2, demonstrating that the coordination of the complex 3 on the MSNPs 1 surface generates strong luminescence. In EtOH, the emission of the MSNPs 2 is centered at a similar wavelength (λem = 590 nm) with a quantum yield of 0.019. This quantum yield is based upon a comparison with that of [Ru(bipy)3] 2+ in air-equilibrated aqueous solution (ϕem = 0.028).

Figure 3.

Diffuse reflectance UV–vis spectrum and emission spectrum obtained upon excitation into MLCT adsorption band of a water suspension of MSNPs 2.

The MSNPs 2 display photophysical properties that are unexpected for dppz-based systems: although they are luminescent in nonaqueous environments, in common with other dppz-based complexes, they are effectively emissive in water which is at odds with most ruthenium(II) complexes containing dppz ligands.8 For comparison, while the ruthenium complex 2 shows appreciable solvatochromic luminescence in EtOH (λem = 603 nm, ϕem = 0.002) and MeCN (λem = 610 nm, ϕem = 0.005), it does not luminesce in aqueous solution. The emission of the complex, after grafting on the MSNPs, can be interpreted in terms of the shielding of dppz ligand from water molecules. The emission intensity increases along with the higher grafting coverage by the ruthenium(II) complex but without being directly proportional (Figure S19). Indeed, the photophysical properties of dppz-based systems are affected by the local environment and the concentration of the complex on the surface. The emission characteristics of a dppz-based complex, [Ru(bipy)2(dppz)]2+, have been studied28 previously in a micellar environment. This investigation suggests that in the case of micellar solutions, water molecules cannot quench the emission of the dppz ligand, since the ligand is efficiently buried in the hydrophobic micellar core.

In order to lend further support to the enhanced emission of ruthenium(II) complex after grafting on MSNPs, we applied the same protocol to functionalized nonporous solid nanoparticles (SNPs). The synthesized SNPs are spherical in shape and have an average particle size of 100 nm, with no obvious mesoporosity, as confirmed by TEM and N2 adsorption–desorption analysis (Figures S23 and S24). The cocondensation of the ligand L on those nanoparticles, giving SNPs 1, followed by coordination with 3 in the dark, afforded SNPs 2. The coordination of the ruthenium(II) complex with the benzonitrile ligand grafted on the surface of those nanoparticles has been elucidated by FT-IR and 29Si CP-MAS solid-state NMR spectroscopies (Figures S20 and S21). The photophysical properties of these newly synthesized SNPs 2 were investigated (Figures S25–S27) in water and compared with those of MSNPs 2. Excitation of SNPs 2 at 450 nm shows an emission maximum centered on 585 nm with a quantum yield ϕem = 0.013 (0.018 for MSNPs 2). All these observations are consistent with the coordination of the ruthenium(II) complex onto the surface of the nanoparticles. The organization of the complex allows the dppz ligand to be shielded from water molecules, as observed in the case of MSNPs 2.

Light-Triggered Release of Ruthenium(II) dppz Complexes

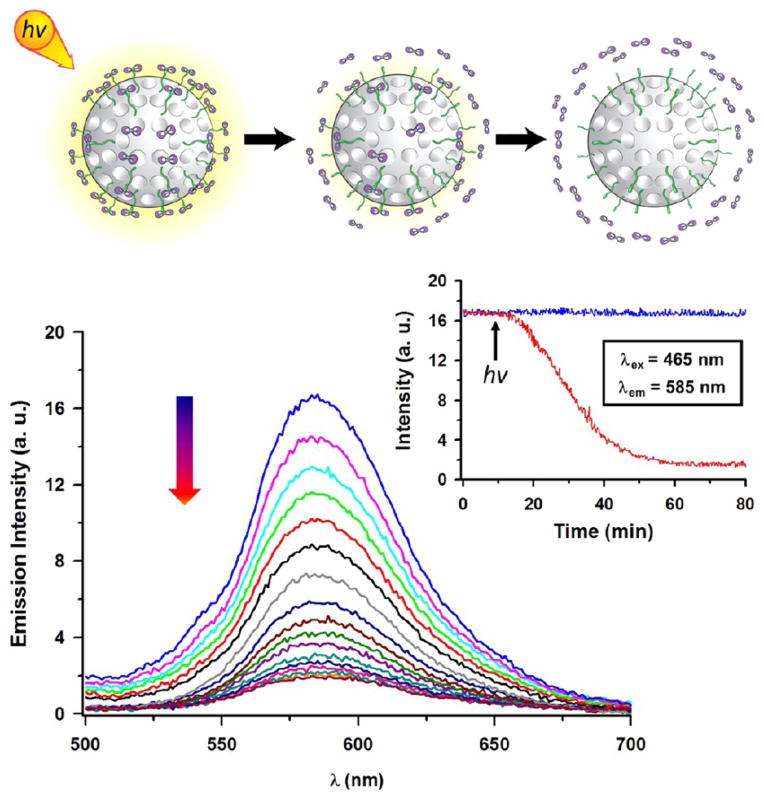

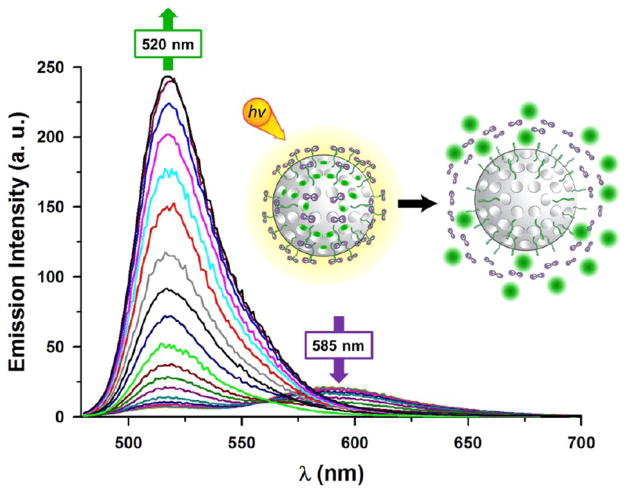

When the MSNPs 2, suspended in water, are irradiated with white light at room temperature, a decrease of the luminescence (Figure 4), concomitant with a gradual color change of the solution to red, is observed. At any point in the experiment, if the irradiation is halted, the emission of the nanoparticles also ceases to evolve, confirming the thermal inertness of the MSNPs 2 in the dark. The emission of the MSNPs 2 was monitored at 585 nm as a function of the irradiation time. Under the conditions of the experiment, the emission decreases to 50% after 30 min and is totally quenched after irradiating for 1 h. The absorption spectrum of the contact solution is characterized by an absorption band at 495 nm, corresponding to that of the aqua complex 3. The decrease of the emission after release of the aqua complex implies that the quenching of the 3MLCT excited state by water is efficient with respect to complex 2 in solution. The exact nature of the photoproduct release from MSNPs 2 was confirmed by light irradiation experiments in D2O, followed by ultracentrifugation of the sample and analysis of the supernatant and the precipitated MSNPs 2. 1H NMR spectroscopy of the supernatant after centrifugation shows the characteristic resonance of the aqua complex [Ru(terpy)(dppz)(H2O)]2+, while only traces of the ruthenium complex are detected on the nanoparticles after light irradiation (Figures S29 and S30). These observations are consistent with the release of the ruthenium complex into the solution, resulting in the effective quenching of the complex by water molecules. The 1H NMR spectroscopic data were used to ascertain that 0.222 μmol of aqua complex, extracted from an appropriate calibration curve, is released from 5 mg of MSNPs 2 after 1 h of irradiation, corresponding to a release of 0.3 wt %.

Figure 4.

Emission spectra and the corresponding release profile of the ruthenium(II) aqua complex from a water suspension of MSNPs 2 on irradiation with visible light. The sample was irradiated with visible light, and the spectra were recorded every 3 min at an excitation wavelength of 465 nm. The release profile (inset) was monitored at 585 nm under continuous light irradiation (red curve). The stability of the MSNPs 2 (blue curve) was tested under dark conditions.

Upon photoexcitation of the MLCT band, ruthenium polypyridyl complexes are known to photosubstitute selectively one ligand in the coordination sphere by a water molecule. Indeed, we have found (as confirmed by UV–vis and 1H NMR spectroscopies) that photolysis of 2 in aqueous solution yields quantitatively the aqua complex 3. On light irradiation for 1 h, the MLCT absorption band, initially centered on 450 nm, shifts to a longer wavelength (495 nm) as a result of the photoexpulsion of the ligand. The photosubstitution of the ligand by a water molecule, giving [Ru(terpy)(dppz)(H2O)]2+, has also been confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. These results highlight that the surface environment does not modify the photosubstitution properties of the ruthenium complex to any significant extent. The thermal stability of the ruthenium(II) complex coordinated to the surface of the nanoparticles, MSNPs 2 and SNPs 2, was evaluated in the dark by following the emission spectra and the 1H NMR spectra of the contact solution in D2O at 37 °C. For both nanoparticles, no significant decrease of the quantum yield was detected after the first 3 days, and no trace of the aqua complex in solution was detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy. After 2 weeks a small amount of the aqua complex had formed in the solution and a decrease of ~8% in the quantum yield was noted.

DNA Binding Experiments

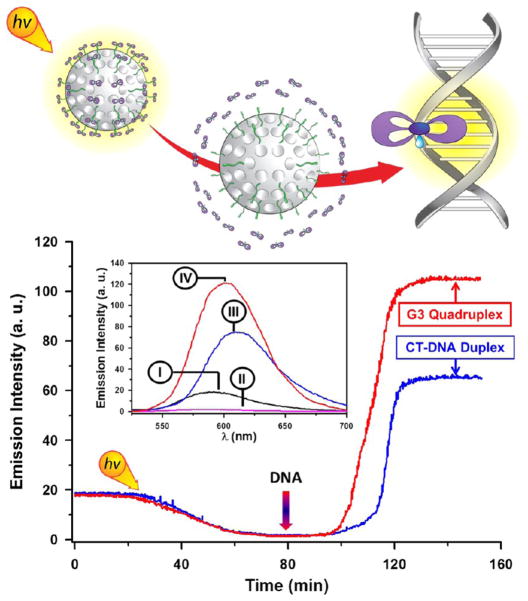

The successful light-induced release of the ruthenium(II) complex from the surface of nanoparticles allows control and switching of the activity of biological processes in both time and space. The unique feature of ruthenium(II) complexes incorporating a dppz ligand is their intercalation in the DNA minor groove and subsequent formation of monoadducts. The main driving force behind the intercalation of those complexes is most likely the stacking interactions between the pyrazine rings of the dppz ligand and the base pair of DNA duplex. In this closely packed superstructure, the dppz ligand does not make contact with any of the surrounding water molecules directly,29 resulting in the activation of the luminescence of the complex. There is a great deal of interest currently7 in using such a system to image directly DNA in living cells. In order to probe these processes, we selected a duplex and G3 quadruplex DNA as model systems to test the ability of the released complex to discriminate between different DNA structures. Hence, the photochemical activation of the ruthenium complex on the MSNPs 2 and the ability to interact with DNA after release was evaluated in buffered solution by fluorescence spectroscopy.

A sample of the MSNPs 2 was dispersed in pH 7.0 buffer solution, and the emission intensity of the solution was monitored at 585 nm. The emission intensity of the MSNPs 2 decreases upon irradiation, consistent with the decoordination of the nitrile ligand from the ruthenium(II) complex, facilitated by the coordination of a water molecule, and the release of the aqua ruthenium(II) complex. The photochemically driven loss of luminescence reaches a plateau after 1 h of irradiation. The addition of calf-thymus DNA (CT DNA), to achieve a final concentration of 20 μM, results (Figure 5) in the reactivation of the emission of the released aqua complex. The luminescence enhancement occurs within minutes of DNA addition, indicating that the association rate is relatively rapid. In contrast to the behavior of the ruthenium(II) complex grafted onto nanoparticles (λem = 585 nm), however, the emission maximum, after intercalation in the double-stranded DNA, is shifted to 615 nm. This effect has been reported8a for analogues dppz–ruthenium complexes and has been rationalized by using the same arguments employed to explain the light switch of [Ru(bipy)2(dppz)]2+.

Figure 5.

Emission spectra of ruthenium-grafted MSNPs before (I) and after (II) irradiation with visible light (pH 7.0 Tris buffer, 5 mM, 25 mM NaCl, 25 °C). Reactivation of the emission occurred after addition of calf-thymus DNA (CT-DNA) (III) or G3 quadruplex (G3-DNA) (IV) set at a concentration of 20 μM. The emission profile was evaluated at an excitation wavelength of 465 nm and emission of 585 nm.

The ability of the released complex to discriminate between different DNA structures, such as quadruplex DNA, has also been explored. Indeed, the stabilization of quadruplex DNA in G-rich sequences of DNA located at the end of chromosomes is recognized as an anticancer strategy.30 In contrast to duplex DNA where the ligands are known to intercalate into the minor groove, the formation of adducts with quadruplex structures seems31 to occur through nonintercalative stacking interactions in an end-capping mode. The human telomeric sequence 22-mer d(AG3[T2AG3]3) [G3] was added to a solution of MSNPs 2 after irradiation with visible light for 1 h. The interaction of the released aqua ruthenium(II) complex with the quadruplex DNA results in an enhancement of the emission of the ruthenium(II) complex. In comparison with the emission of the complex intercalated in the duplex DNA, the interaction with the DNA quadruplex is characterized by an emission enhancement of 1.5-fold and a shift of the emission maximum to 602 nm, implying that the complex is less accessible to water molecules as a consequence of a greater overlap between the dppz ligand and the DNA bases. This conclusion is reinforced by previous in vitro studies which demonstrated the high affinity of dinuclear ruthenium(II) complexes to quadruplex DNA.30 These results confirm the selectivity and sensitivity of the ruthenium(II) complex after its release from MSNPs to intercalate into DNA.

The interaction of the MSNPs 2 with double-stranded and quadruplex DNA was tested (Figure S31) in the dark. Only minute changes in the emission of the MSNPs 2 were observed after addition of DNA in the dark, indicating a low interaction of DNA with the ruthenium(II) complex grafted onto the nanoparticles. The hybrid system is found to be unreactive in the dark but is transformed upon light activation and subsequent ruthenium release to be able to form monoadducts to DNA. In contrast with the agents that bind DNA on the basis of their chemical reactivity, this hybrid system has the advantage that it can be activated selectively in both time and space using light, likely minimizing the toxic side effects within healthy tissue.

Light-Activated Release of Cargo Molecules

The functioning of this light-activated release system was then tested for dual drug release, a cytotoxic cargo loaded into the MSNP pores and the ruthenium(II) complex grafted on the surface. Indeed, the ruthenium(II) complex coordinated on the periphery of the pores acts as a capping agent, blocking the pore openings. In order to verify the operation of the light-responsive nanovalve system, the ligand-functionalized MSNPs 1 were first of all loaded by soaking in concentrated solutions of the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel (Ptx). The loaded nanoparticles were then capped with the aqua ruthenium(II) complex at room temperature and washed carefully (see Supporting Information for experimental details). The amount of paclitaxel taken up by the MSNPs 1 during the loading process, defined as the uptake efficiency (see Supporting Information for more details), was calculated from the difference in concentrations of the solution before and after loading, as quantified (Figures S32 and S34) by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). At 2 mM Ptx loading concentration, an uptake efficiency of 82% was reached by the MSNPs, while the Ptx loading capacity of the nanoparticles was estimated to be around 5.2%.

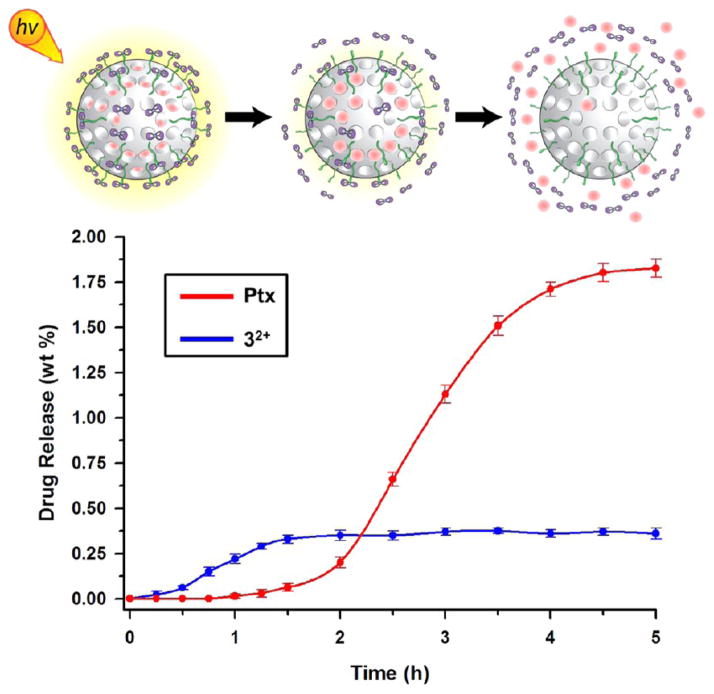

The capped and loaded nanoparticles were placed in a dialysis membrane (3000 Da cutoff), and the release of the cargo molecules was evaluated by HPLC analysis. The controlled and temporally distinct release of Ptx and the aqua ruthenium(II) complex (32+) was observed (Figure 6) under light irradiation from paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles, MSNPs 2 Ptx. Upon irradiation with light, a rapid release of the ruthenium(II) complex from the MSNPs surface was observed, whereas the Ptx, trapped in the porous structure, exhibits delayed release from the nanoparticles following removal of the ruthenium(II) complex cap. According to the HPLC measurements (see the Supporting Information), approximately 0.11 μmol of Ptx is released from 5 mg of MSNPs 2, which corresponds to a 1.8% release capacity. The amount of released Ptx divided by the total amount of drug loaded in the nanoparticles’ pores, defined as the release efficiency, was quantified to be as high as 35%. The release profile for the docetaxel-loaded MSNPs 2 was also evaluated, and the loading and release parameters for this drug-loaded nanoparticles are given in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Step-by-step dual release profile of aqua ruthenium(II) complex (blue trace) and paclitaxel (Ptx) (red trace) from MSNPs 2 under visible light irradiation. The release studies were performed at room temperature in water.

Table 1.

Uptake and Release Capacity and Efficiency for the MSNPs 2 Loaded with Anticancer Drugs and Fluorescence Cargos

| uptake capacity (%) | uptake efficiency (%) | release capacity (%) | release efficiency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| paclitaxel | 5.2 | 82 | 1.8 | 35 |

| docetaxel | 4.8 | 75 | 2.2 | 47 |

| cyanine 5 | 5.5 | 87 | 1.1 | 20 |

| fluorescein | 3.2 | 49 | 2.6 | 82 |

| calcein | 5.0 | 79 | 1.5 | 24 |

The ability of this system to regulate drug release in a temporally controlled fashion by first triggering the photoexpulsion of the cap from the nanoparticles’ surface was also tested by loading the MSNPs’ pores with fluorescent cargo molecules, such as fluorescein, calcein, or cyanine 5. The dual release of the rutherium(II) complex and the dye, loaded in the MSNPs 2, was monitored (Figures S36–S38) by fluorescence spectroscopy upon excitation at a single wavelength. The time-dependent dual-luminescence features of the calcein-loaded MSNPs 2 system under irradiation with visible light are shown in Figure 7. Calcein was selected as a cargo for dual-release experiments because its fluorescence self-quenches while it is entrapped inside the pores of the particles, whereas after it is released from the pores it becomes diluted and fluoresces in solution.32 Irradiation with visible light results in a decrease of the luminescence of the peak associated with the ruthenium(II) complex grafted on the MSNPs 2, centered at 585 nm, and the concomitant increase in the emission intensity around 520 nm occurred showing that the calcein is released from the nanopores of the MSNPs with a release capacity of approximately 1.5%. These results further demonstrate that the cargo-loaded MSNPs 2 can release the ruthenium(II) complex and the cargo in a stepwise fashion. The uptake and release capacity of the MSNPs 2 loaded with the different fluorescent cargo molecules are summarized in Table 1. The trapped and releasable amounts of the cargo, in agreement with previous release experiments on nanovalve-gated MSNPs,33 would provide a better control over the delivery process for both in vitro and in vivo applications.

Figure 7.

Release of calcein-loaded MSNPs 2 on irradiation with visible light. Emission spectra for the release of calcein and ruthenium(II) aqua complex from an aqueous suspension of MSNPs 2. The sample was irradiated with visible light, and the spectra were recorded every 3 min at an excitation wavelength of 465 nm.

Cellular Uptake and Localization

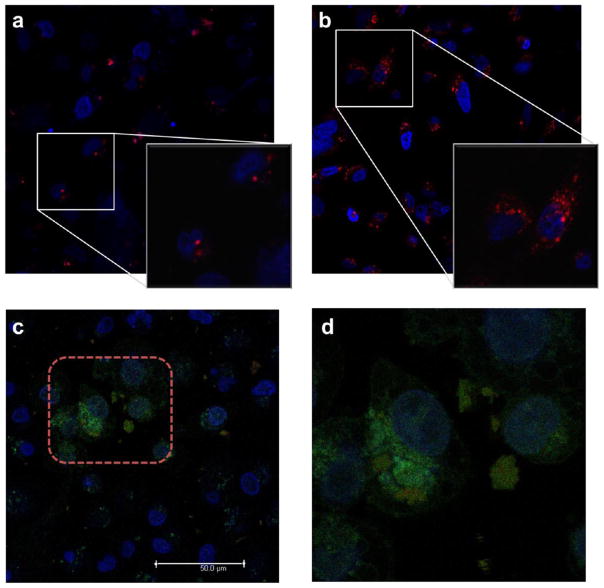

In order to determine whether the light-operated nanoparticles remain functional under biologically relevant conditions, the photophysical properties of MSNPs 2 have been used to evaluate their localization in breast cancer cells. We anticipated that the luminescence properties of MSNPs 2 would not be significantly solvent-dependent, while the localization of the aqua ruthenium(II) complex after release would be possible if the complex was directed to a hydrophobic environment, since the luminescence of these compounds is quenched in aqueous media.

Confocal microscopy (Figure 8a,b) revealed the red emission from the ruthenium(II) complexes grafted onto the nanoparticle surface upon excitation at 458 nm. The localization of the MSNPs 2 inside the cells, rather than being bound to the exterior, was confirmed by Z-scan experiments, showing that the observed luminescence is spherical in three dimensions (see Supporting Information video). After exposing the cells to the visible light irradiation (30 min), an increase of the luminescence was localized mainly in the cytoplasm with only a weak signal being detected in the nucleus. This result can be attributed to the detachment of ruthenium(II) complexes from the nanoparticles and the subsequent diffusion of the complex into the cytoplasm. Since the aqua ruthenium(II) complex exhibits luminescence in a hydrophobic environment, we postulate that it may become localized in cytoplasmic organelles, giving a red emission spectra (Figure 8b). The localization of polypyridyl ruthenium complexes in the mitochondria has been reported,34 and this cellular compartment has been considered7e,35 recently as a target of such compounds.

Figure 8.

Confocal images of MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells treated with nonactivated (a) or light activated (b) MSNPs 2. Confocal images (c, d) showing MSNPs 2 loaded with FITC uptake by MDA-MB-468 cells after photoactivation in the selected region (red square) for 30 min. The merged view shows the red emission from ruthenium(II) aqua complex (λex = 458 nm, λem = 590–630 nm), the green emission from fluorescein (λex = 488 nm, λem = 500–530 nm), and the blue emission from DAPI (λex = 405 nm, λem = 440–470 nm). Note an effective increased emission (d) from fluorescein inside the irradiated area (red square), while the nonactivated region displays a lower intensity.

In order to demonstrate the applicability of the light-activated nanoparticles for the release of ruthenium(II) complex and encapsulated cargo molecules in quick succession in the intracellular environment, fluorescein-loaded nanoparticles MSNPs 2 FITC were photoactivated in situ and the release was monitored in real time by confocal microscopy. The remote activation of a chemical event inside the cell and the subsequent spectroscopic monitoring of the biological responses are an emergent way to evaluate drug delivery nanodevices inside a single living cell.36 The in vitro performance of MSNPs 2 FITC was evaluated in real time by irradiation of a confined region with a 458 nm light using the confocal microscope while monitoring directly on the stage (Figure 8c,d). A local enhanced and more widespread luminescence, with an emission band at 510–520 nm, was observed in the cells irradiated with the laser (localized within the red square in Figure 8c), while no change in the emission of fluorescein was detected in the nonactivated area. Under the conditions used in the experiments, nonspecific photodamage of cells was not observed. This experiment demonstrates that the activation of the nanoparticles and the subsequent release of cargo molecules take place only in the region irradiated with light. The spatiotemporal control of cargo release from light-activated nanoparticles has important consequences for the efficacy and safety of drug delivery, particularly chemotherapeutic agents.

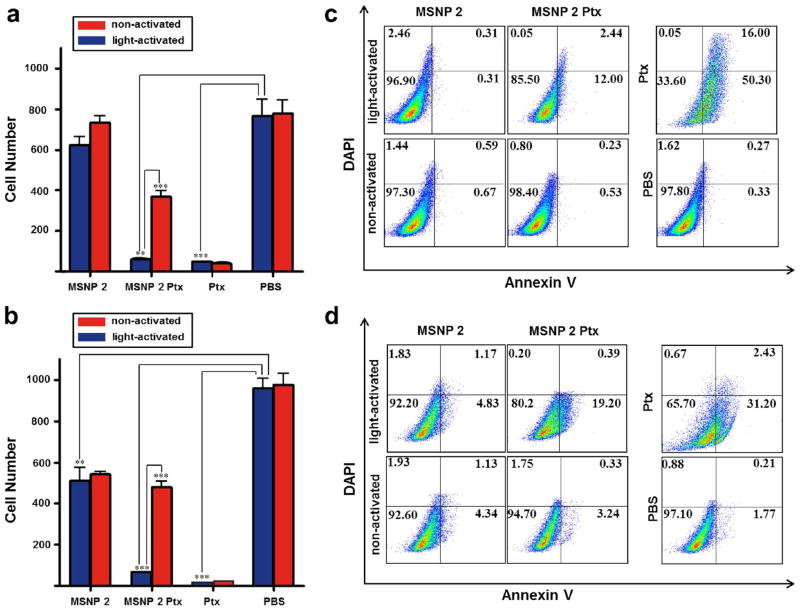

Cytotoxicity Studies

The suitability of the modified nanoparticles for the light-activated release of cytotoxic cargo was tested in human breast cancer cells using a crystal violet cell survival assay. Breast cancer cells were treated with MSNPs 2, MSNPs 2 Ptx, free Ptx, or phosphate buffer solution (PBS). The cytotoxicity was evaluated using the amount of drug effectively released from the nanoparticles, considering a release capacity for the MSNPs 2 Ptx of approximately 1.8%. The cells were maintained in the dark for 24 h after adding the nanoparticles and then subjected to 50 min of light exposure (activation). The number of surviving cells was scored after incubation for an additional 72 h. Under these conditions, empty MSNPs 2 had no significant cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Figure 9a and Figure S45a) and only modest cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells (Figure 9b and Figure S45b). In contrast, light activation enhanced the cytotoxicity of MSNPs 2 Ptx dramatically against both breast cancer cell lines but had no effect on the cytotoxicity of free paclitaxel.

Figure 9.

Cell survival of MDA-MB-231 (a) and MDA-MB-468 (b) breast cancer cells treated with 5 μg mL−1 MSNPs 2, 5 μg mL−1 MSNPs 2 Ptx, 100 ng mL−1 free Ptx or PBS for 96 h without light activation (red bars) or with visible-light activation (blue bars). For light activation, the cells were exposed to light for 50 min 24 h after adding the nanoparticles and then incubated for an additional 72 h. Crystal violet was employed to stain the surviving cells. The data are presented as the mean and the standard error of the mean (SEM) of three experiments ((***) P < 0.001, (**) P < 0.01). Annexin V flow cytometry assay of MDA-MB-231 (c) and MDA-MB-468 (d) breast cancer cells treated with 5 μg mL−1 MSNPs 2, 5 μg mL−1 MSNPs 2 Ptx, 100 ng mL−1 free Ptx or PBS for 72 h with or without visible-light activation. For light activation, the cells were exposed to light for 50 min 24 h after adding the nanoparticles and then incubated for an additional 48 h. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is indicated.

In order to assess the cytotoxic mechanism of MSNPs 2 Ptx, an annexin V assay was performed (see Supporting Information for experimental details). In agreement with the cell survival assay results, light activation of MSNPs 2 Ptx increased apoptosis induction dramatically, as determined by the percentage of annexin V-positive cells, in MDA-MB-231 (Figure 9c) and MDA-MB-468 (Figure 9d) breast cancer cells. The annexin V studies have demonstrated that the free drug induces more cell death than MSNPs 2 Ptx, an observation that may reflect the delayed release of the encapsulated cytotoxic cargo from the nanoparticles in the cellular environment. Although there is increased interest in the cellular uptake of transition metal complexes, no delivery platforms for the systematic delivery of metal complexes have been reported to date. It is worthy of note that the ruthenium complexes may augment the cytotoxity of released Ptx by inducing DNA damage.34 Collectively, these results demonstrate that light activation triggers drug release from MSNPs and enhances their cytotoxicity against breast cancer cells.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have demonstrated a versatile strategy for light activation and light-triggered delivery of biologically active ruthenium–dppz complexes. The surface-grafted ruthenium complex on MSNPs can be activated by visible light irradiation. The nitrile ligand fixed on the surface of the MSNPs acts as a protecting group. The ruthenium-containing prodrug is activated once the aqua ruthenium complex is obtained and released after photosubstitution. Subsequently, the drug reaches the targeted location. The hybrid system displays attractive photophysical properties, such as enhanced luminescent properties, relative to the ruthenium(II) dppz complex in homogeneous phase, an observation that can be used to track the complexes in biological studies. While unreactive in the dark, the ruthenium complex on the MSNPs is transformed upon light activation into the cytotoxic aqua complex, which is able to form monoadducts with DNA and act as an effective DNA light-switching complex. Importantly, the cell studies establish that the ruthenium-modified nanoparticles are stable in the intracellular environment; no loss of luminescence is evident, as would be expected, based upon changes in complex coordination. An informative aspect of using mesoporous silica nanoparticles as the vehicle for the delivery of ruthenium complexes is that while the complexes are attached to the nanoparticles surface by a photocleavable coordination bond, another drug can be stored in the nanopores of the MSNPs with temporal control over its release. Indeed, the use of light to activate cytotoxic agents is an attractive feature and is receiving increasing attention37 owing to the possibility of developing systems that would allow fine spatiotemporal control of drug release: the release of the drug at the irradiated site would potentially increase the drug retention in cancers and reduce side-effects. The proposed system has the potential for the convenient adaptation to cytotoxic ruthenium(II) compounds with different biochemical properties for cancer treatment where combination therapy is desired. This photoactive drug delivery system holds promise as a multifunctional nanomedicine with dual imaging and therapeutic purposes and a wide range of potential biomedical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was performed under the auspices of the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) and Northwestern University (NU) Joint Center of Excellence for Integrated Nanosystems (JCEIN). We thank Dr. Turki S. Al-Saud and Dr. Mohamed B. Alfageeh for their support of this research. We also thank Dr. Andrey Ugolkov at the Center for Developmental Therapeutics and Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center (NU) for providing cell lines. Imaging work was performed at the NU Biological Imaging Facility. J.L. acknowledges the Chinese Scholarship Council for providing financial support during her stay at NU. Y.W. thanks the Fulbright Scholar Program for a Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Detailed synthetic procedures and characterization (NMR and HRMS) data for the ruthenium(II) complexes, synthetic procedures and characterization (13C-CPMS NMR, 29Si-CPMS NMR, FT-IR, XPS, PXRD, TEM, DR UV–vis, and emission spectroscopy) data for the functionalized MSNPs and SNPs, physicochemical characterization of cargo-loaded MSNPs, cellular uptake and localization studies, cytotoxicity characterization of drug-loaded MSNPs, and two video files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Dolmans EJGJ, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Ackroyd R, Kelty C, Brown N, Reed M. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:656–669. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0656:thopap>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:535–545. doi: 10.1038/nrc1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Celli JP, Spring BQ, Rizvi I, Evans CL, Samkoe KS, Verma S, Pogue BW, Hasan T. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2795–2838. doi: 10.1021/cr900300p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mitsunaga M, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Rosenblum LT, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Nat Med. 2011;12:1685–1691. doi: 10.1038/nm.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:185–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Gianferrara T, Bratsos I, Alessio E. Dalton Trans. 2009;38:7588–7598. doi: 10.1039/b905798f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu HK, Sadler PJ. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:349–359. doi: 10.1021/ar100140e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gasser G, Ott I, Metzler-Nolte N. J Med Chem. 2011;54:3–25. doi: 10.1021/jm100020w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Young Park G, Wilson JJ, Song Y, Lippard SJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;108:11987–11992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207670109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Komor AC, Barton JK. Chem Commun. 2013;49:3617–3630. doi: 10.1039/c3cc00177f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Liu W, Gust R. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:755–773. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35314h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambron JC, Sauvage JP, Turro NJ, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4960–4962. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Albano G, Belser P, De Cola L, Gandolfi MT. Chem Commun. 1999:1171–1172. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ossipov D, Gohil S, Chattopadhyaya J. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13416–13433. doi: 10.1021/ja0269486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lim MH, Song H, Olmon ED, Dervan EE, Barton JK. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:5392–5397. doi: 10.1021/ic900407n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lutterman DA, Chouai A, Liu Y, Sun Y, Stewart CD, Dunbar KR, Turro C. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1163–1170. doi: 10.1021/ja071001v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Vanderlinden W, Blunt M, David CC, Moucheron C, Kirsch-De Mesmaeker A, De Feyter S. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10214–10221. doi: 10.1021/ja303091q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Elmes RBP, Kitchen JA, Williams DC, Gunnlaugsson T. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:6607–6610. doi: 10.1039/c2dt00020b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Puckett CA, Barton JK. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:46–47. doi: 10.1021/ja0677564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gill MR, Garcia-Lara J, Foster SJ, Smythe C, Battaglia G, Thomas JA. Nat Chem. 2009;1:662–667. doi: 10.1038/nchem.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Elmes RB, Orange KN, Cloonan SM, Williams DC, Gunnlaugsson T. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15862–15865. doi: 10.1021/ja2061159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gill MR, Thomas JA. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3179–3192. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15299a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pierroz V, Joshi T, Leonidova A, Mari C, Schur J, Ott I, Spiccia L, Ferrari S, Gasser G. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20376–20387. doi: 10.1021/ja307288s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Turro C, Bomann SH, Jenkins Y, Barton JK, Turro NJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:9026–9032. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stewart DJ, Fanwick PE, McMillin DR. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:6814–6816. doi: 10.1021/ic1010117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) McKinley AW, Lincoln P, Tuite EM. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255:2676–2692. [Google Scholar]; (d) Walker MG, Gonzalez V, Chekmeneva E, Thomas JA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:12107–12110. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niyazi H, Hall JP, O’Sullivan K, Winter G, Sorensen T, Kelly JM, Cardin CJ. Nat Chem. 2012;4:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song H, Kaiser JY, Barton JK. Nat Chem. 2012;4:615–620. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Durham B, Caspar JV, Nagle JK, Meyer TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4803–4810. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vögtle F, Plevoets M, Nieger M, Azzellini GC, Credi A, De Cola L, De Marchis V, Venturi M, Balzani V. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6290–6298. [Google Scholar]; (c) Campagna S, Puntoriero F, Nastasi F, Bergamini G, Balzani V. Top Curr Chem. 2007;280:117–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Hecker CR, Fanwick PE, McMillin DR. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:659–666. [Google Scholar]; (b) Laemmel AC, Collin JP, Sauvage JP. Eur J Inorg Chem. 1999:383–386. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mobian P, Kern JM, Sauvage JP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:2392–2395. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bonnet S, Collin JP. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1207–1217. doi: 10.1039/b713678c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Howerton BS, Heidary DK, Glazer EC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8324–8327. doi: 10.1021/ja3009677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wachter E, Heidary DK, Howerton BS, Parkin S, Glazer EC. Chem Commun. 2012;48:9649–9651. doi: 10.1039/c2cc33359g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Schofield E, Collin JP, Gruber N, Sauvage JP. Chem Commun. 2003:188–189. doi: 10.1039/b210607h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bonnet S, Collin JP, Sauvage JP, Schofield E. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:2392–2395. doi: 10.1021/ic0491736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldbach RE, Rodriguez-Garcia I, van Lenthe JH, Siegler MA, Bonnet S. Chem— Eur J. 2011;17:9924–9929. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Bonnet S, Limburg B, Meeldijk JD, Gebbink RJMK, Killian JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:252–261. doi: 10.1021/ja105025m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bahreman A, Limburg B, Siegler MA, Koning R, Koster AJ, Bonnet S. Chem— Eur J. 2012;18:10271–10280. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:615–627. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mout R, Moyano DF, Rana S, Rotello VM. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2539–2544. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15294k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pelaz B, Jaber S, Jimenez de Aberasturi D, Wulf V, Aida T, de la Fuente JM, Feldmann J, Gaub HE, Josephson L, Kagan CR, Kotov NA, Liz-Marzán LM, Mattoussi H, Mulvaney P, Murray CB, Rogach AL, Weiss PS, Willner I, Parak WJ. ACS Nano. 2012;6:8468–8483. doi: 10.1021/nn303929a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rana S, Bajaj A, Mout R, Rotello VM. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2012;64:200–216. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Kolishetti N, Dhar S, Valencia PM, Lin LQ, Karnik R, Lippard SJ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17939–17944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011368107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Okuda T, Tominaga K, Kidoaki S. J Controlled Release. 2010;143:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Youan BBC. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62:898–903. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Coti KK, Belowich ME, Liong M, Ambrogio MW, Lau YA, Khatib HA, Zink JI, Khashab NM, Stoddart JF. Nanoscale. 2009;1:16–39. doi: 10.1039/b9nr00162j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vivero-Escoto JL, Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Lin VSY. Small. 2010;6:1952–1967. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Coll C, Bernardos A, Martínez-Máñez R, Sancenón F. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:339–349. doi: 10.1021/ar3001469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Liong M, Lu J, Kovochich M, Xia T, Ruehm SG, Nel AE, Tamanoi F, Zink JI. ACS Nano. 2008;2:889–896. doi: 10.1021/nn800072t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lu J, Choi E, Tamanoi F, Zink JI. Small. 2008;4:421–426. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2590–2605. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tarn D, Ashley CE, Xue M, Carnes EC, Zink JI, Brinker CJ. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:792–801. doi: 10.1021/ar3000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Meng H, Liong M, Xia T, Li Z, Ji Z, Zink JI, Nel AE. ACS Nano. 2010;4:4539–4550. doi: 10.1021/nn100690m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ashley CE, Carnes EC, Phillips GK, Padilla D, Durfee PN, Brown PA, Hanna TN, Liu J, Phillips B, Carter MB, Carroll NJ, Jiang X, Dunphy DR, Willman CL, Petsev DN, Evans DG, Parikh AN, Chackerian B, Wharton W, Peabody DS, Brinker CJ. Nat Mater. 2011;10:389–397. doi: 10.1038/nmat2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pan L, He Q, Liu J, Chen Y, Ma M, Zhang L, Shi J. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5722–5725. doi: 10.1021/ja211035w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ashley CE, Carnes EC, Epler KE, Padilla DP, Phillips GK, Castillo RE, Wilkinson DC, Wilkinson BS, Burgard CA, Kalinich RM, Townson JL, Chackerian B, Willman CL, Peabody DS, Wharton W, Brinker CJ. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2174–2188. doi: 10.1021/nn204102q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Park C, Oh K, Lee SC, Kim C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:1455–1457. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao YL, Li Z, Kabehie S, Botros YY, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13016–13025. doi: 10.1021/ja105371u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guillet-Nicolas R, Popat A, Bridot JL, Monteith G, Qiao SZ, Kleitz F. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:2318–2322. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Angelos S, Choi E, Vögtle F, De Cola L, Zink JI. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:6589–6592. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aznar E, Casasús R, García-Acosta B, Marcos MD, Martínez-Máñez R, Sancenón F, Soto J, Amorós P. Adv Mater. 2007;19:2228–2231. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu J, Bu W, Pan L, Shi J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:4375–4379. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, Jeftinija K, Xu S, Jeftinija S, Lin VSY. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu R, Zhao X, Wu T, Feng P. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14418–14419. doi: 10.1021/ja8060886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang C, Li Z, Cao D, Zhao YL, Gaines JW, Bozdemir OA, Ambrogio MW, Frasconi M, Botros YY, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:5460–5465. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Bernardos A, Mondragón L, Aznar E, Marcos MD, Martínez-Máñez R, Sancenón F, Soto J, Barat MJ, Pérez-Payá E, Guillem C, Amorós P. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6353–6368. doi: 10.1021/nn101499d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Singh N, Karambelkar A, Gu L, Lin K, Miller JS, Chen CS, Sailor MJ, Bhatia SN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19582–19585. doi: 10.1021/ja206998x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Park C, Kim H, Kim S, Kim C. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:16614–16615. doi: 10.1021/ja9061085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z, Balogh D, Wang F, Willner I. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1934–1940. doi: 10.1021/ja311385y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambron JC, Sauvage JP. Chem Phys Lett. 1991;182:603–607. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall JP, O’Sullivan K, Naseer A, Smith JA, Kelly JM, Cardin CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17610–17614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108685108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajput C, Rutkaite R, Swanson L, Haq I, Thomas JA. Chem— Eur J. 2006;12:4611–4619. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Gavathiotis E, Heald RA, Stevens MF, Searle MS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:4749–4751. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4749::aid-anie4749>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Clark GR, Pytel PD, Squire CJ, Neidle S. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4066–4067. doi: 10.1021/ja0297988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel H, Tscheka C, Heerklotz H. Soft Matter. 2009;5:2849–2851. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Nyalosaso JL, Hwang AA, Ferris DP, Yang S, Derrien G, Charnay C, Durand JO, Zink JI. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:19496–19506. doi: 10.1021/jp2047147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisani MJ, Fromm PD, Mulyana Y, Clarke RJ, Körner H, Heimann K, Collins JG, Keene FR. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:848–858. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan C, Lai S, Wu S, Hu S, Zhou L, Chen Y, Wang M, Zhu Y, Lian W, Peng W, Ji L, Xu A. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7613–7624. doi: 10.1021/jm1009296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau YA, Henderson BL, Lu J, Ferris DP, Tamanoi F, Zink JI. Nanoscale. 2012;4:3482–3489. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30524k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(a) Kang H, Trondoli AC, Zhu G, Chen Y, Chang YJ, Liu H, Huang YF, Zhang X, Tan W. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5094–5099. doi: 10.1021/nn201171r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rong T, Hemmati HD, Langer R, Kohane DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8848–8855. doi: 10.1021/ja211888a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang Y, Yin Q, Yin L, Ma L, Tang L, Cheng J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:6435–6439. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.