Summary

Background

The use of plasma-derived immunoglobulin G (IgG) is increasing, and the number of diseases, including immunodeficiencies, neurological diseases and autoimmune conditions, treated with intravenous IgG (IVIG) is expanding. Consequently, there is a great need for high-yield production processes for plasma-derived IgG. The aim of this work was to develop a high-yield process leading to a highly purified, liquid, ready-to-use IgG for intravenous use.

Methods

Plasma from healthy, voluntary, non-remunerated donors was fractionated by ethanol precipitation. IgG was extracted from fraction II + III using a phosphate/acetate buffer, pH 4, and purified by chromatography.

Results

Precipitation with 6% polyethylene glycol at pH 7 removed high molecular-weight contaminating proteins, aggregates and contaminating viruses. Ion exchange chromatography at pH 5.7 on serially connected anion and cation exchange columns allowed for elution of IgG from the cation exchange column in good yield and high purity. Further safety was achieved by solvent/detergent treatment and repeated ion exchange chromatography. The product consisted of essentially only IgG monomers and dimers, and had a high purity with very low levels of IgM and IgA.

Conclusion

A process providing highly purified IVIG in good yield was developed.

Keywords: Chromatography, Immunoglobulin G, Intravenous, Polyethylene glycol precipitation

Introduction

Immunoglobulins (Igs; antibodies), of which there are 5 classes (M, D, G, A, E) and a number of subclasses (IgG1–4, IgA1, 2), are major contributors to the immune defence, and failure to produce certain antibodies results in susceptibility to infections [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Ig deficiencies are classified as primary (congenital) and secondary (acquired), and manifest themselves as immunodeficiency syndromes, most commonly a deficiency in IgG or IgA subclasses [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Besides these Ig deficiencies, individuals may experience difficulties in producing antibodies against specific infectious agents [12]. Ig deficiencies can be treated by administration of purified preparations of plasma-derived antibodies, which have also been found to modulate some autoimmune diseases, e.g. idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. For these reasons, there is strong interest in the clinical uses of purified human Igs and methods for their production. The first process for Ig isolation from human plasma was devised by Cohn et al. [20]. This method used graduated ethanol fractionation, and was later modified by Oncley [21] and Kistler and Nitschmann [22]. The purity of the Ig preparations obtained by these methods was adequate for subcutaneous and intramuscular use but could give rise to side effects due to impurities and aggregated or denatured antibody molecules, especially if given intravenously [23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Also, the subcutaneous and intramuscular administration imposed limits on the amounts that could be administered. Intravenous administration of Igs was therefore preferred, requiring highly purified products. In reality, this could be achieved by chromatographic purification, and therefore state of the art processes for Ig purification employ 1 or more column chromatography steps in addition to several means of reducing the transmission of possible contaminating viruses or other pathogens [29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. The aim of this work was to develop a high-yield process leading to a pure, safe, liquid IgG preparation for intravenous use (IVIG).

Material and Methods

Materials

Chemicals were of pharmaceutical or analytical grade. DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow and CM Sepharose were from GE Healthcare Bio-sciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Tris-glycine gels were from NOVEX (San Diego, USA). GelCode Blue staining reagent, and Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) Protein Assay Kit were from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Litex agarose HSA 1000 was from Cambrex Bio Science (Copenhagen, Denmark). Filter aid and C-150AF depth filter were from Schenk (Bad Kreuznach, Germany). Planova 15N and 20N nanofilters were from Asahi Kasei Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). Fluorodyne II filter was from Pall (New York, USA). Delipid, 50LA and 90LA depth filters were from Cuno (Meriden, CT, USA). Sterile filters (0.22 µm, Durapore) and polysulfone membranes (30 kDa cut-off and 100 kDa cut-off) were from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). 0.45 µm filters were from Pall Corporation (Portsmouth, UK). Sartobran filters and Sartopure GF 2 filters were from Sartorius (Goettingen, Germany). MaxiSorp plates were from Nunc (Roskilde, Denmark). Human serum albumin (HSA) was from Statens Serum Institut (SSI; Copenhagen, Denmark). Rabbit antibodies against human IgM, IgA, HSA and α2-macroglobulin, and Human Serum Protein Calibrator were from DakoCytomation (Copenhagen, Denmark). Horse radish peroxidase(HRP)-conjugated streptavidin was from Zymed (San Francisco, CA, USA). Alkaline phosphatase(AP)-conjugated goat antibodies against mouse and rabbit Igs were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Plasma

Plasma was from voluntary, non-remunerated Danish blood donors, and was recovered as citrate plasma which was immediately frozen after separation by centrifugation. All donations were screened for viruses according to current guidelines [35].

Ethanol Fractionation

Plasma was thawed at 5 °C, and the cryoprecipitate removed by centrifugation. The plasma was then processed by ethanol fractionation according to Kistler and Nitschmann [22]. Initially, fraction I + II + III was precipitated and used as starting material. In subsequent work, fraction I was first precipitated and then fraction II + III was precipitated.

Extraction and Purification of IgG from Paste II + III

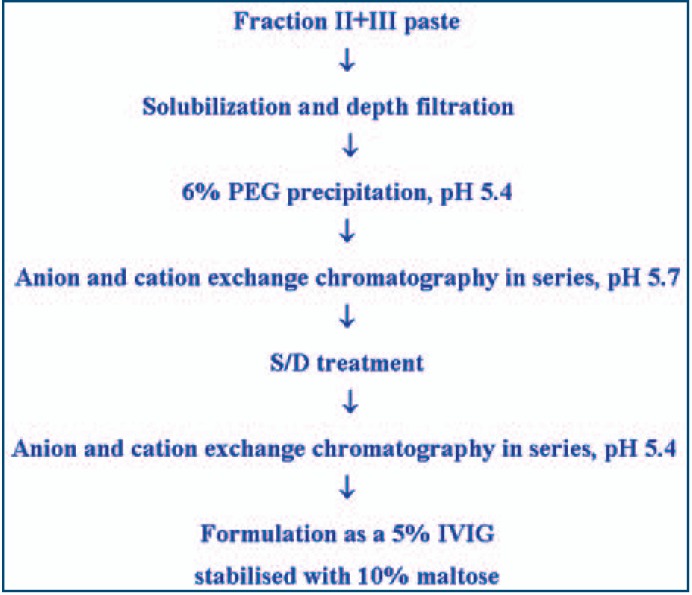

The following steps (1–6) constituted the IVIG SSI process (fig. 1). All steps were carried out at 5 °C unless otherwise stated.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the production process for IVIG liquid SSI.

Ig Extraction

To 140 kg fraction II + III paste (approximately 1,150 kg starting plasma), including 30 kg filter aid, were added 525 kg 2.33 mmol/l sodium phosphate/acetate buffer, pH 4.0, over 1.5 h with gentle stirring. Then, 2 portions of 350 kg water for injection (WFI) were added over 1.5 h each with gentle stirring. Finally, the pH was adjusted to 5.4 by addition of approximately 280 kg 21.5 mmol/l sodium phosphate/acetate, pH 7.0. The suspension was filtered through a C-150AF depth filter.

PEG Precipitation

To the filtrate from the Ig extraction was slowly added polyethylene glycol (PEG) 6000 to a final concentration of 6% (w:w), and the mixture stirred for 4 h at 5 °C. The suspension was clarified in a BKA28 flow-through centrifuge (GEA Westfalia, Oelde, Germany), passed through 50LA and 90LA depth filters, and sterile-filtered through a 0.22 µm filter. The pH was adjusted to 5.7 by adding 1 part 0.45 mol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.7, with 29 parts filtrate.

Column Chromatography

Two columns were packed with 56 l of DEAE Sepharose FF or CM Sepharose, respectively. The columns were connected in series, DEAE column first, and equilibrated in 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.7. Then, the filtered supernatant from the PEG precipitation (volume corresponding to approximately 2.250 kg) was applied to the columns. After washing with 1 column volume of 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, the columns were disconnected. The CM column was washed with 3 column volumes of 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, and eluted by a gradient from 125 to 350 mmol/l sodium chloride (NaCl) in 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4. The IgG fraction was collected in sorbitol solution (final concentration 2.5% w:w).

Solvent/Detergent (S/D) Treatment

The eluted IgG was concentrated and desalted by ultra/diafiltration against 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, 2.5% sorbitol (w:w) to approximately 50 g IgG/l (measured by A280) and a conductivity < 1.4 mS/cm2 using a 30 kDa cut-off polysulfone membrane (final volume corresponding to approximately 120 kg). The sorbitol concentration was adjusted to 10%, and the solution filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. Tween 80® (Sigma) and tri-n-butyl phosphate (TNBP) were added to 1% and 0.3% (w:w), respectively, and the solution incubated for a minimum of 6 h at 25 °C.

Removal of Tween 80 and TNBP

The solution from the S/D treatment was diluted with 5 parts of 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, filtered through a 90 LA filter and then through a sterile filter, and applied to serially connected columns packed with 28 l DEAE Sepharose and 56 l CM Sepharose, respectively, and equilibrated with 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4. After washing with 1 column volume of 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, the columns were disconnected. The CM column was washed with 6 column volumes of 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, and then eluted by a gradient from 125 to 350 mmol/l NaCl in 15 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4. The IgG fraction was collected in maltose solution (final concentration 2.5% w:w).

Formulation

The IgG from step 5 was ultra/diafiltered (100 kDa cut-off polysulfone membrane) against 7.5 mmol/l sodium acetate, pH 5.4, 2.5% maltose (w:w) to a conductivity < 1 mS/cm. The IgG concentration was adjusted to 50 g/l, and the maltose concentration adjusted to 10% (w:w). Finally, the solution was filtered through a Sartopure GF 2 filter, and filled aseptically in glass bottles.

Virus Validation Studies

Downscaled process steps (40 ml) simulating the PEG precipitation and S/D treatment steps of the production process were used for validation of the virus-removing and -inactivating capacity according to EU guidelines [35, 36] (Sanquin Virus Validation Services, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Analyses

Unless otherwise stated, analyses were carried out as described in the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) [37] including total protein content (Kjeldahl), IgG monomer/dimer/oligomer/aggregates (size exclusion chromatography), anticomplementary activity (ACA), prekallikrein activator (PKA), hemagglutinins, and Tween 80, TNBP and PEG content.

Purity

Purity (protein composition) was analysed by electrophoresis as described in the Ph. Eur. [37], except that agarose gels were used instead of cellulose acetate gels. After staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, protein bands were quantified by densitometry (GS-800 densitometer, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Albumin Content

Albumin was measured by crossed immunoelectrophoresis (CIE) as described [38]. A rabbit HSA antiserum was used 1:100 for the second dimension.

IgG Content

IgG was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm (extinction coefficient for IgG, ε0.1% = 1.4 cm2/mg).

IgG Subclass Distribution

IgG subclasses were quantified by radial immunodiffusion as described [39], using a WHO reference serum (67/97) for calibration.

IgA and IgM Content

The content of IgA and IgM was measured by radial immunodiffusion [39] and by in-house capture ELISAs (with rabbit anti-IgM or anti-IgA as capture antibodies and the corresponding peroxidase-conjugated antibodies as detecting antibodies, all from DAKO, Copenhagen) using a calibrated reference serum (X908) for calibration.

Maltose Concentration

The content of maltose was determined using a commercial kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) with maltose as a reference.

Multiplex Analysis

Multiplex analyses were done by MyriadRBM (Austin, Texas, USA) with Luminex-based Multi-Analyte (MAP) technology (www.myriadrbm.com/products-services/humanmap-services/humanmap/). Results are expressed as averages of 2 batches of IVIG.

Clinical Studies

Clinical studies were conducted in accordance with EU guidelines [40, 41, 42]. First, an open prospective phase I/II trial with patients with primary immunodeficiency syndromes (PID), secondary immunodeficiency syndromes (SID), ITP and CIDP was carried out. Later, a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial with patients with optic neuritis (ON) was carried out. Patients received IVIG as slow infusions (0.1–1 mg/kg/min) at recommended doses (depending on the group). Vital signs and clinical parameters were monitored. Additionally, parameters like recovery, half-life and trough values of total IgG and IgG subclasses, infections, days in hospital, days out of work/school, use of antibiotics, days of fever, signs of bleeding, rise and duration of platelet counts and adverse events were recorded, depending on the patient group. Viral markers were assayed prior to and after the study period.

Results

Process Development

To secure a stable product without IgG aggregates, a strategy was chosen to treat the proteins as gently as possible during the production process. Therefore, all purification steps were performed at 5 °C. Furthermore, extremely acidic and basic conditions were avoided. Conditions with low ionic strength and stabilization with sugar were used whenever possible.

Final Production Process

The final production process is shown in figure 1. It started from precipitate B (fraction II + III paste), which was resuspended in sodium phosphate/acetate buffer, pH 4, and extracted for 3 h to solubilise IgG. After filtration, precipitation with PEG 6000 (6%) removed high molecular weight proteins and aggregates. During chromatography at pH 5.7 on the serially connected ion exchange columns IgG passed through the DEAE column and bound to the CM column, whereas most other plasma proteins bound to the DEAE column. The subsequent washing with acetate buffer, pH 5.4, further removed traces of contaminating proteins. Elution of the CM column with a gradient of NaCl led to a chromatographically pure IgG fraction which was subjected to S/D treatment. Removal of S/D chemicals by a second chromatography step on serially connected columns further removed impurities, and ultra/diafiltration using a 100 kDa cut-off filter also eliminated contaminating proteins. Finally, the product was formulated as a 5% sterile solution stabilized with 10% maltose. The yield relative to the starting plasma was 3.7 g IgG/kg (mean of 7 consecutive batches).

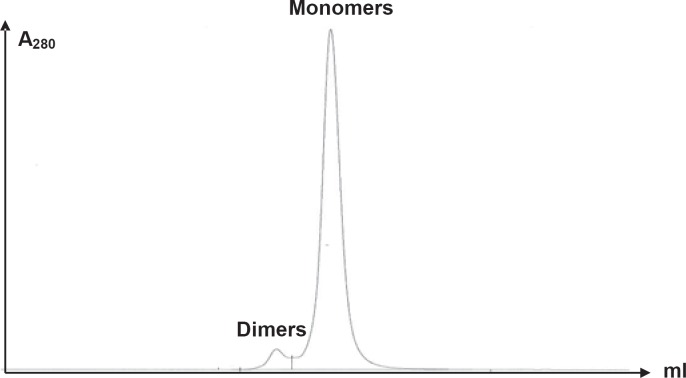

Product Characterization

Table 1 shows selected characteristics of IVIG liquid SSI. No albumin could be detected in the final product which consisted of 99.8% IgG (monomers/dimers) without oligomers or aggregates. The average IgM content was 0.3 mg/l, and the average IgA content was 2.7 mg/l. The IgG subclass distribution was within the normal range [43], with 57% IgG1, 38% IgG2, 3% IgG3 and 2% IgG4. The content of a range of other possible contaminating proteins was measured by multiplex analysis (table 2). This confirmed the low IgM and IgA content and showed that other proteins were essentially absent, with only trace amounts of fibrinogen, α2macroglobulin, apolipoprotein A1, C3, beta-2-microglobulin and von Willebrand factor being detectable. The purity of IVIG liquid SSI is illustrated in figure 2 which shows that the product contained essentially only monomeric and dimeric IgG molecules. This homogeneity could be ascribed to the chromatography on the serially connected ion exchange columns. The content of specific Igs was determined for tetanus toxoid (TT), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and parvovirus B10 antibodies. The content of TT and CMV antibodies were 6.2 and 6.6 times, respectively, higher than in the starting plasma pool (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of IVIG liquid SSI

| Characteristic | Ph. Eur. specification | SSI specification | Average of 8 batches IVIG liquid SSI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purity | >95% of the total protein content | ≥97% of the total protein content | 100% IgG |

| Distribution of molecular size of IgG | ≤3% polymeric | ≤2% polymeric | <0.2% polymeric |

| ≥90% monomeric/dimeric IgG | ≥95% monomeric/dimeric IgG | 99% monomeric/dimeric IgG | |

| Anti-complementary activity (ACA) | complement use ≤50% | Ph.Eur. | 27.2% |

| PKA activity | ≤35 IU/ml | Ph.Eur. | <8.5 IU/ml |

| Fc function | ≥60% of IVIG reference preparation | Ph.Eur. | 112% |

| Hemagglutinins anti A and anti B | 1/64 diluted solution shows no agglutination | 1/16 diluted solution shows no agglutination | undiluted solution shows no agglutination |

| pH | 5.1–5.7 | 5.5 | |

| IgA content | <4 mg/l | 2.7 mg/l | |

| IgM content | <1 mg/l | 0.31 mg/l | |

| IgG subclass distribution | IgG distribution corresponding to normal human serum | defined distribution of subclasses reflecting the normal range of serum | IgG1 57% |

| IgG2 38% | |||

| IgG3 3% | |||

| IgG4 2% | |||

| Anti-tetanus | ≥3 × starting plasma pool | Ph.Eur. | 6.2 × starting plasma pool |

| Anti-CMV | ≥3 × starting plasma pool | Ph.Eur. | 6.6 × starting plasma pool |

Table 2.

Multiplex analysis of IVIG liquid SSI contents

| Compound | Concentration |

|---|---|

| Alpha-2-macroglobulin | 0.37 mg/l |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | 0.09 µg/l |

| Apolipoprotein A1 | 0.15 mg/l |

| Apolipoprotein CIII | 0.05 mg/l |

| Apolipoprotein H | not detectable |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | 2.5 mg/l |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | not detectable |

| C3 | 0.19 mg/l |

| CA-125 | 2.6 U/ml |

| Calcitonin | 1.6 ng/l |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | 1.9 µg/l |

| Creatine kinase | 0.31 µg/l |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | not detectable |

| ENA-78 | not detectable |

| Fatty acid-binding protein (FABP) | 9.1 µg/l |

| Factor VII | 27 µg/l |

| Ferritin | 0.40 µg/l |

| Fibrinogen | 0.51 mg/l |

| Growth hormone | 0.28 µg/l |

| Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) | 2.3 ng/l |

| Glutathione S transferase (GST) | 0.15 µg/l |

| Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) | 1.1 µg/l |

| IgA | 2.6 mg/l |

| IgE | not detectable |

| IgM | 0.55 mg/l |

| Interleukin (IL)-1alpha | not detectable |

| IL-1beta | 0.58 µg/l |

| IL-2 | not detectable |

| IL-3 | not detectable |

| IL-4 | 1.38 µg/l |

| IL-5 | not detectable |

| IL-6 | not detectable |

| IL-7 | not detectable |

| IL-8 | not detectable |

| IL-10 | 1.08 µg/l |

| IL-12p40 | not detectable |

| IL-12p70 | not detectable |

| IL-13 | not detectable |

| IL-15 | not detectable |

| IL-16 | not detectable |

| IL-18 | not detectable |

| Insulin | not detectable |

| Leptin | 0.1 µg/l |

| Lipoprotein | not detectable |

| Lymphotoxin | not detectable |

| Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) | 163 ng/l |

| Macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC) | not detectable |

| Macrophage inhibitory protein-1beta (MIP-1beta) | not detectable |

| Matrix metalloprotease-3 (MMP-3) | 0.20 µg/l |

| Myoglobin | not detectable |

| Prostate acid phosphatase (PAP) | not detectable |

| Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (free) | 6.4 ng/l |

| Regulated on activation, normal T cell-expressed (RANTES) | 0.22 ng/l |

| Serum amyloid P (SAP) | 52 ng/l |

| Stem cell factor (SCF) | not detectable |

| Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) | 0.11 mg/l |

| Thyroxine | not detectable |

| Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases-1 (TIMP-1) | 125 µg/l |

| Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)alpha | 24 ng/l |

| TNFbeta | not detectable |

| Thrombospondin | not detectable |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | 0.57 mIU/l |

| vonWillebrand factor (vWF) | 4.5 mg/l |

Fig. 2.

Distribution of IgG forms in IVIG liquid SSI analysed by size exclusion chromatography.

Alternative Starting Materials

IVIG liquid SSI was produced from fraction II + III (precipitate B) obtained by the method of Kistler and Nitschmann [22]. Alternative starting materials, e.g. paste II + III obtained by the method of Cohn [20] or Oncley [21], could be used with equally excellent results (not shown).

Stability

A stability study showed a shelf life of at least 24 months at 2–8 °C (table 3). A small accelerated stability study at 37 °C showed a stability comparable to other IVIG products measured as % content of polymers, aggregates and fragments (results not shown).

Table 3.

Stability of IVIG liquid SSI (mean ± standard deviation of 3 batches)

| Test | 0 months | 12 months | 24 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | slightly opalescent and colourless | slightly opalescent and colourless | slightly opalescent and colourless |

| pH | 5.4 ± 0.05 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.06 |

| Total protein, mg/ml | 48.7 ± 0.6 | 51.7 ± 1.5 | 51.7 ± 2.1 |

| Protein composition, % IgG | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Anticomplementary activity, % C consumption | 34.8 ± 2.4 | 32.3 ± 2.7 | 37.9 ± 6.5 |

| Composition | |||

| % IgG mono + dimers | 98.4 ± 0.4 | 100 | 99.6 ± 0.04 |

| % IgG polymer/aggregates | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| % fragments | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0 | 0.35 ± 0.03 |

| Subclass distribution | |||

| % IgG1 | 55.3 ± 0.6 | 55.3 ± 0.6 | 55 ± 1.0 |

| % IgG2 | 40.3 ± 1.5 | 40 ± 1 | 40.7 ± 1.2 |

| % IgG3 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| % IgG4 | 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.0 |

| IgA, mg/l | 2.8 ± 0.3 | ND | 2.9 ± 0.4 |

| IgM, mg/l | 0.41 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.21 ± 0.02 |

| Fc-function, % of BRF reference | 104 ± 2.6 | 106 ± 4 | ND |

| PKA activity, IU/ml | <8.5a | <8.5a | <8.5a |

| Hemagglutinins anti A + anti B titer/dilution for agglutination | 0 + 0 | ND | 1 + 1 |

| Anti-tetanus, IU/ml | 10.1 ± 0.4 | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 9.1 ± 0.8 |

| Anti-CMV, U/ml | 946 ± 192 | 1229 ± 102 | 1,094 ± 77 |

| Osmolality, mOsm/kg | 366 ± 4 | ND | 366 ± 2 |

| Maltose, mg/ml | 97.3 ± 0.7 | 93.4 ± 0.8 | 98.7 ± 2.1 |

Lower quantification level.

C = Complement; ND = Not determined.

Virus Safety

Virus removal by PEG precipitation and virus inactivation by S/D treatment were validated in studies employing 4 or 5 viruses (table 4). PEG precipitation at pH 5.4 was shown to be a general efficient virus removal step, including both enveloped and small non-enveloped viruses. The robustness of the virus-removing capacity in studies employing the 2 viruses CPV and hepatitis A virus (HAV) was validated by variation of the PEG concentration, pH and protein concentration within the normal ranges showing the virus removing efficiency of the PEG precipitation to be very robust (results not shown). Also, the robustness of the S/D treatment was validated in studies varying the concentration of S/D chemicals, time and temperature (results not shown). As to parvovirus B19 safety, the rate of seropositivity in the Danish population is about 60% and therefore the anti-parvovirus B19 titre in IVIG liquid SSI was accordingly high, measured as a mean of 282 IU/ml of 12 batches. Whenever present in the starting material, parvovirus B19 will be neutralised by specific antibodies and/or eliminated as immune complexes by PEG precipitation.

Table 4.

Virus reduction efficacy of 2 steps in the manufacturing process of IVIG liquid SSI; minimal reduction factors are shown

| Reduction Log10 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | BVDV | PRV | Polio | HAV | Sindbis | CPV | |

| S/D treatment | 7.4 | 4.1 | 5.1 | ND | ND | 5.3 | ND |

| PEG precipitation | 7.6 | 7.5 | ND | 7.2 | 6.3 | ND | 7.4 |

ND = Not determined

Clinical Efficacy and Safety

The in vitro Fc function of IVIG SSI liquid was intact (112%), and the product showed low ACA (27.2%) and PKA activity (< 8.5 IU/ml). The in vivo half-life (T½) was measured to be 30.5 days (median), corresponding to that of other preparations [44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49]. The mean recovery of IgG was 85%, and trough values were above 4 g/l in all but 1 of the PID and SID patients. No seroconversions were seen.

Hospitalisation, days on antibiotic treatment, days with fever, and episodes of pneumonia were registered retrospectively in 6 months in patients with primary and secondary hypogammaglobulinemia who had been treated with other IVIG preparations and then received IVIG liquid SSI for 6 months (table 5). There were no significant differences in these parameters between periods of IVIG liquid SSI treatment and earlier IVIG treatment. No seroconversions were reported.

Table 5.

Clinical studies with IVIG liquid SSI

| Indication | Patients, n | Duration, months | Infusions, n | Dose | Results | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PID | 15 | 6 | 131 | 0.2–0.4 g/kg 2–5 weeks interval | T½ = 30.4 days trough levels > 4g/l | no seroconversion 14 adverse events |

| SID | 6 | 6 | 52 | 0.2–0.4 g/kg 2–5 weeks interval | T½ = 30.4 days trough levels > 4g/l | no seroconversion 5 adverse events |

| ITP | 15 | 6 | 28 | 0.4 g/kg per day in 5 days or 1 g/kg in 2 days | platelets > 50×109/l no signs of bleeding | no seroconversion 15 adverse events |

| CIDP | 5 | 6 | 17 | 80–120 g over 1–5 days 2–20 weeks interval | effect equal to previous treatment (Rankin score) | no seroconversion 21 adverse events |

| ON | 34 | 6 | 158 | 0.4 g/kg days 0, 1, 2, 30, and 60 | no effect on visual parameters | no seroconversion 97 adverse events |

| Total | 75 | 386 | ||||

In patients with ITP, the number of platelets generally increased from < 30 × 109/l to at least 50 × 109/l after treatment (table 5). 1 patient did not respond to treatment. The increase in the number of platelets and the duration of remission in 5 of the patients, who had been treated previously, was comparable to treatment with other IVIG preparations. No seroconversions were reported.

In patients with CIDP, IVIG liquid SSI showed the same clinical efficacy as previous (6 months) treatment with other products, judged by self-assessment of physical abilities (Rankin score) and measurement of muscle strength (table 5).

Together, 55 adverse events, including 15 definite treatment-related adverse events, occurred in the 41 patients with PID, SID, ITP or CIDP. Of the 15 events, 13 were mild, while 1 patient experienced a moderately intense acute eczema on hands and feet and another patient experienced moderate fever, headache and arthralgia for 2 days. All patients recovered completely. No seroconversions were reported.

In a phase III clinical trial, 68 patients with acute ON were randomised to IVIG liquid SSI or placebo [50]. There was no difference in the primary outcome (contrast sensitivity) after 6 months. There was no significant difference in the total number of adverse events or in the number or frequency of specified adverse events between treatment groups. The adverse events were mainly mild, however, 1 patient experienced aseptic meningitis [50]. No serocoversions were reported.

Following marketing authorisation in Denmark, a total amount of 850 kg IVIG liquid SSI was administered to patients during a period of 5 years (1999–2003). In this period, only few minor adverse events were reported (12 in total), including cases of skin rash, fever, rigors and dyspnoea. No serious adverse events were reported. No seroconversions were reported. The adverse events reported were either unrelated to IVIG liquid SSI or previously known to be associated with Ig infusions as described in the literature [42, 51, 52].

Discussion

IVIG is an effective treatment for several immunodeficiencies and autoimmune conditions [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Due to this and the limited availability of plasma, effective manufacturing processes are of great interest. Most current manufacturing processes for IVIG products use a combination of ethanol fractionation and ion exchange chromatography, and yield products with acceptable purity and safety profiles [32, 33, 53]. However, differences exist due to variations in starting materials, fractionation conditions and virus safety procedures.

The process of IVIG production described in this paper was developed with a strategy to treat the proteins as gently as possible and to avoid extremes of pH and other process parameters, and resulted in a highly purified, stable, safe, liquid IgG. The high purity could be ascribed to the chromatographic steps using serially connected anion and cation exchange columns. The chromatographic conditions were designed to allow IgG to pass through the anion exchange column and bind to the cation exchange column, while other plasma proteins bound to the anion exchange column. This allowed for separate elution of the IgG from the cation exchange column. The remainder of the process consisted of S/D treatment, polishing and formulation steps to yield a highly pure, stable product for intravenous use. Compared with other processes, the IVIG SSI process was more elaborate, as it involved 2 chromatographic steps on serially connected columns. However, this was compensated by the purity and functional activity of the final product, as evidenced by a very low content of IgM and IgA, virtual absence of hemagglutinins, low content of other proteins, and a high content of functional IgG monomers and dimers with a natural subclass distribution.

The starting material for the process was fraction II + III from Kistler/Nitschmann fractionation. Fraction I + II + III could also be used, but this resulted in a higher PKA content of the IgG product. Fraction II + III from Cohn Oncley fractionation also appeared to be a suitable starting material, attesting to the versatility of the process.

The process involved 2 validated virus-removing/inactivating steps – PEG precipitation and S/D treatment. However, we have shown that the product could be nanofiltered through Planova 15 N nanofilters (results not shown) without significant product loss, enabling further viral elimination safety.

The clinical safety and efficacy of IVIG liquid SSI was tested with good results in several groups of patients, including PID, SID, ITP, CIDP and ON patients. During these studies, only 2 persons experienced treatment-related serious adverse events, 1 case of acute eczema and 1 case of aseptic meningitis. In particular, no thromboembolic events were reported. The safety of IVIG liquid SSI was further documented by the total use of 850 kg with only 12 reported adverse events, many unrelated to the IVIG. In conclusion, the process described here led to a highly pure, safe, liquid IgG product for intravenous administration.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Statens Serum Institut held a patent on the process for IVIG liquid SSI from 2000 to 2010.

Acknowledgement

Inga A. Laursen passed away 11.12.2011. This paper is dedicated to her memory.

References

- 1.Oxelius VA. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) subclasses and human disease. Am J Med. 1984;76:7–18. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Söderström T. Söderström R. Avanzini A. Brandtzaeg P. Karlsson G. Hanson LA. Immunoglobulin G subclass deficiencies. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1987;82:476–480. doi: 10.1159/000234258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gross S. Blaiss MS. Herrod HG. Role of immunoglobulin subclasses and specific antibody determinations in the evaluation of recurrent infection in children. J Pediatr. 1992;121:516–522. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss RB. Carmack MA. Esrig S. Deficiency of IgG4 in children: association of isolated IgG4 deficiency with recurrent respiratory tract infection. J Pediatr. 1992;120:16–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latiff AH. Kerr MA. The clinical significance of immunoglobulin A deficiency. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44:131–139. doi: 10.1258/000456307780117993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood P. Stanworth S. Burton J. Jones A. Peckham DG. Green T. Hyde C. Chapel H. Recognition, clinical diagnosis and management of patients with primary antibody deficiencies: a systematic review. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:410–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notarangelo LD. Lanzi G. Peron S. Durandy A. Defects of class-switch recombination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castigli E. Geha RS. Molecular basis of common variable immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ming JE. Stiehm ER. Graham JM. Syndromes associated with immunodeficiency. Adv Pediatr. 1999;46:271–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirchandani N. Hawit F. Silverberg NB. Cutaneous signs of neonatal and infantile immunodeficiency. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:176–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stiehm RE. The four most common pediatric immunodeficiencies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:15–26. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strunk T. Richmond P. Simmer K. Currie A. Levy O. Burgner D. Neonatal immune responses to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:370–375. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3281a7ec98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Söderström T. Söderström R. Enskog A. Immunoglobulin subclasses and prophylactic use of immunoglobulin in immunoglobulin G subclass deficiency. Cancer. 1991;68:1426–1429. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910915)68:6+<1426::aid-cncr2820681404>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wordell CJ. Use of intravenous immune globulin therapy: an overview. DICP. 1991;25:805–817. doi: 10.1177/106002809102500717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirofsky B. Kinzey DM. Intravenous immune globulins. A review of their uses in selected immunodeficiency and autoimmune diseases. Drugs. 1992;43:6–14. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199243010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García JM. Español T. Gurbindo MD. Casas CC. Update on the treatment of primary immunodeficiencies. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2007;35:184–192. doi: 10.1157/13110313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibéril S. Elluru S. Negi VS. Ephrem A. Misra N. Delignat S. Bayary J. Lacroix-Desmazes S. Kazatchkine MD. Kaveri SV. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: more than mere transfer of antibodies. Transfus Apher Sci. 2007;37:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ephrem A. Misra N. Hassan G. Dasgupta S. Delignat S. Van Huyen JP. Chamat S. Prost F. Lacroix-Desmazes S. Kavery SV. Kazatckine MD. Immunomodulation of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with intravenous immunoglobulin. Clin Exp Med. 2005;5:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s10238-005-0079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra N. Bayry J. Ephrem A. Dasgupta S. Delignat S. Van Huyen JP. Prost F. Lacroix-Desmazes S. Nicoletti A. Kazatchkine MD. Kveri SV. Intravenous immunoglobulin in neurological disorders: a mechanistic perspective. J Neurol. 2005;252:I1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-1102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohn EJ. Strong LE. Hughes WL. Mulford DJ. Ashworth JN. Melin M. Taylor HL. Preparation and properties of serum and plasma proteins III. A system for the separation into fractions of the protein and lipoprotein components of biological tissues and fluids. J Am Chem Soc. 1946;68:459–475. doi: 10.1021/ja01207a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oncley JL. Melin M. Richert DA. Cameron JW. Gross PM. The separation of antibodies, isoagglutinins, prothrombin, plasminogen and beta-lipoprotein into subfractions of human plasma. J Am Chem Soc. 1949;71:541–550. doi: 10.1021/ja01170a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kistler P. Nitschmann H. Large scale production of human plasma fractions. Eight years experience with the alcohol fractionation procedure of Nitschmann, Kistler and Lergier. Vox Sang. 1962;7:414–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1962.tb03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rousell RH, McCue JP. Antibody purification from plasma. In: Harris JP, editor. Blood Separation and Plasma Fractionation. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1991. pp. 307–340. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misbah SA, Chapel HM. Adverse effects of intravenous immunoglobulin. Drug Saf. 1993;9:254–262. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199309040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nydegger UE, Sturzenegger M. Adverse effects of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Drug Saf. 1999;21:171–185. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199921030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierce LR, Jain N. Risks associated with the use of intravenous immunoglobulin. Transfus Med Rev. 2003;17:241–251. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(03)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamrock DJ. Adverse events associated with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz U, Achiron A, Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Safety of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah S. Pharmacy considerations for the use of IGIV therapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:S5–S11. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelfand EW. Differences between IGIV products: impact on clinical outcome. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegel J. Safety considerations in IGIV utilization. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchacher A, Iberer G. Purification of intravenous immunoglobulin G from human plasma – aspects of yield and virus safety. Biotechnol J. 2006;1:148–163. doi: 10.1002/biot.200500037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin TD. IGIV: contents, properties, and methods of industrial production – evolving closer to a more physiologic product. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kempf C, Stucki M, Boschett N. Pathogen inactivation and removal procedures used in the production of intravenous immunoglobulins. Biologicals. 2007;35:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Council of Europe Note for Guidance on Plasma-Derived Medicinal Products 2001. CPMP/BWP/269/95, rev. 3, London, 25 January

- 36.Council of Europe Note for Guidance on Virus Validation Studies: The Design Contribution and Interpretation of Studies Validating the Inactivation and Removal of Viruses 1996. CPMP/BWP/268/95, Final Version 2, London, 29 February

- 37.Council of Europe. European Pharmacopeia (Ph. Eur.) 6th ed. Strasbourg, France: European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laurell CB. Antigen-antibody crossed electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1965;10:358–361. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ingild A. Single radial immunodiffusion. Scand J Immunol. 1983;17:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Council of Europe Guideline on the Clinical Investigation of Human Normal Immunoglobulin for Intravenous Administration (IVIg) 2000. CPMP/BPWG/388/95 rev. 1, London, 29 June

- 41.Council of Europe Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice 2002. CPMP/ICH/135/95. London, July

- 42.Council of Europe Core SPC for Human Normal Immunoglobulin for Intravenous Administration (IVIg) 2004. CPMP/BPWG/859/ 95 rev. 1, London, 29 July

- 43.Djurup R, Mansa B, Søndergaard I, Weeke B. IgG subclass concentrations in sera from 200 normal adults and IgG subclass determination of 106 myeloma proteins: an interlaboratory study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1988;48:77–83. doi: 10.3109/00365518809085397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wasserman RL, Church JA, Stein M, Moy J, White M, Strausbaugh S, Schroeder H, Ballow M, Harris J, Melamed I, Elkayam D, Lumry W, Suez D, Rehman SM. Safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of a new 10% liquid intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:663–669. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9656-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berger M, Pinciaro PJ, Althaus A, Ballow M, Chouksey A, Moy J, Ochs H, Stein M. Efficacy, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of Flebogamma® 10% DIF, a high-purity human intravenous immunoglobulin, in primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:321–329. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9348-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballow M. Clinical experience with Flebogamma® 5% DIF: a new generation of intravenous immunoglobulins in patients with primary immunodeficiency disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157(suppl 1):22–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wasserman RL, Church JA, Peter HH, Sleasmand JW, Melamede I, Steinf MR, Bichlerg J. Pharmacokinetics of a new 10% intravenous immunoglobulin in patients receiving replacement therapy for primary immunodeficiency. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2009;37:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ballow M, Berger M, Bonilla FA, Buckley RH, Cunningham-Rundles CH, Fireman P, Kaliner M, Ochs HD, Skoda-Smith S, Sweetser MT, Taki H, Lathia C. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a new intravenous immunoglobulin preparation, IGIV-C, 10% (Gamunex™, 10%) Vox Sang. 2003;84:202–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chuch JA, Leibl H, Stein MR, Melamed IR, Rubinstein A, Schneider LC, Wasserman RL, Pavlova BG, Birthisle K, Mancini M, Fritsch S, Patrone L, Moore-Perry K, Ehrlich HJ the US-PID-IGIV 10% Study Group. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of a new 10% liquid intravenous immune globulin (IGIV 10%) in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26:388–395. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-9025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roed HG, Langkilde A, Sellebjerg F, Lauritzen M, Bang P, Mørup A, Frederiksen JL. A double-blind, randomized trial of IV immunoglobulin treatment in acute optic neuritis. Neurology. 2005;64:804–810. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152873.82631.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aronson JK, editor. Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs. 15th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Association of British Neurologists Guidelines for the Use of Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Neurological Diseases 2005. London,

- 53.Radosevich M, Burnouf T. Intravenous immunoglobulin G: trends in production methods, quality control and quality assurance. Vox Sang. 2010;98:12–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2009.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]