Abstract

For vaccine development, it is critical to understand the regulatory mechanisms determining resistance and immunopathology against mycoplasma respiratory diseases. The present study evaluated the contribution of the polarizing cytokines, IFN-γand IL-4, in the regulation of mycoplasma-specific immunity. The absence of a single cytokine, either IFN-γor IL-4, uniquely altered expression of multiple chemokines/cytokines in the lungs of uninfected mice and influenced responses to mycoplasma infection. Most importantly, prior nasal-pulmonary immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice led to exacerbated mycoplasma disease, whereas immunized IL-4−/− mice were dramatically more resistant than wild-type mice. Th2-type responses in IFN-γ−/− mice corresponded to immunopathologic reactions developed after mycoplasma infection or immunization. Thus, adaptive immunity clearly can independently promote either protection or immunopathology against mycoplasma infection, and optimal vaccination appears to be dependent on promoting protective IFN-γ-dependent network, perhaps Th1 responses, while minimizing the impact of IL-4-mediated responses that dampen generation of protective immunity.

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma infections are leading causes of respiratory diseases in humans and animals worldwide. In humans, Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a major cause of respiratory disease, accounting for 30% of pneumonia cases annually in the United States [1, 2]. Mycoplasma pulmonis, a natural pathogen in mice and rats, causes similar symptoms and lesions as M. pneumoniae in humans and mycoplasma infections in other animals [3]. It is an excellent animal model to study host immune responses to mycoplasma respiratory infections. Lymphocyte responses contribute to disease severity [4-6]. They can also confer resistance [7] with local (nasal-pulmonary) immunization most effective against mycoplasma infection [8]. Participation of immune responses in lesion formation complicates development of mycoplasma vaccines. Thus, to develop optimal approaches for vaccination against mycoplasma respiratory diseases, it is critical to understand the regulatory mechanisms affecting immune responses contributing to resistance and immunopathology.

T (Th) helper cell responses can clearly contribute to both resistance and development of inflammatory lesions post-mycoplasma infection. Depletion of CD4+ Th cells in mice results in less severe mycoplasma respiratory disease [9]. No corresponding changes in mycoplasma numbers in the lungs indicate Th cells promote inflammatory lesion development, rather than help control mycoplasma infection. However, we recently found CD4+ Th cells, but not CD8+ T cells, from nasal-pulmonary immunized mice can confer resistance against mycoplasma, and regulation of these responses can influence their effectiveness [10]. Thus, Th cells and their regulation are central in determining the mycoplasma disease severity or protection from infection.

The activation and regulation of different Th cell populations are likely critical to the outcome of mycoplasma disease. Although their role in mycoplasma disease is not known, Th1 and Th2 cells can determine the outcome of other infections [11]. Both Th1- and Th2-type responses are present in lungs of mycoplasma-infected mice [12]. The development of Th1 cells is promoted through the regulatory activity of IFN-γ, while IL-4 supports Th2 cell responses [13, 14]. In a previous study [15], we showed IFN-γ−/− mice generate more severe mycoplasma disease than wild-type mice, but a significant portion of this effect was an impairment of innate immunity with a concomitant increase in mycoplasma numbers due to the loss of IFN-γ. In contrast, there was an indication that IL-4−/− mice were more resistant to infection and disease. Further studies are needed to elucidate the role of these two regulatory cytokines in determining the outcome of mycoplasma infection.

We believed a deficiency in either IFN-γ or IL-4 would result in a change in the expression of normal cytokine networks in the lungs of uninfected mice, influencing subsequent responses to infection. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to determine the impact of these cytokines on chemokine/cytokine responses before and after mycoplasma infection, as well as their contribution in developing protective adaptive immunity in response to nasal-pulmonary immunization. In the current studies, we demonstrated that IFN-γ is a key cytokine involved in generating protective adaptive immunity against mycoplasma infections and suggest that Th1 cell responses are the critical effector cells. In contrast, IL-4 interferes with the development of optimal protection, likely via Th2 cells, increasing severity of lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, immunization and infection

Female BALB/cJ, IFN-γ−/− (C.129S7 (B6)-IFN-γtm1Ts) and IL-4−/− (IL-4tn2Nnt) mice on BALB/c backgrounds (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used between 8-12 wks of age. Before immunization or infection, mice were anesthetized using intraperitoneal injection of ketamine-xylazine. Mice were infected by nasal-pulmonary inoculations of M. pulmonis (UAB CT strain, 2 × 105 CFU/20-μl) [16]. Crude preparations of M. pulmonis membrane were used for immunization and prepared as described [17]. Nasal-pulmonary immunizations were done on days 1 and 7 with M. pulmonis Ag (5-μg in 24-μl) [8]. Unimmunized mice received 24-μl sterile PBS (Hyclone). University of North Texas Health Science Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved these animal studies.

RNA isolation, microarrays and real-time PCR

Total lung RNA was isolated from individual mice as described [18]. RNA concentration and quality were assessed on Experion Automated Electrophoresis System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using Stdsens total Eukaryotic RNA Labchips to verify 18S and 28S rRNA integrity.

Oligo GEArrayR Mouse Inflammatory Cytokines and Receptors Microarrays (SuperArray Bioscience Corp., Frederick, MD) were used to evaluate expression of 113 key genes involved in inflammatory responses [18]. Equal amounts of RNA from individual animals in an experiment were pooled and used for microarrays. Two housekeeping genes (gapdh and ppia) were used to normalize spot densities. Microarray data analyses were performed using the SuperArray GEArray Analysis Suite. Changes in gene expression were considered significant only if there was at least an average of ≥2-fold difference, with no value of ≤1.5 fold in either individual experiment [18].

Real-time RT-PCR was performed on RNA samples from individual lungs using SYBR green to detect amplification of products. PCR primer sets of GAPDH, CCL4, CCL6, CCL8, CXCL10, CXCR3, CCR5, and IL-17a, and real-time SYBR master mix were used (SuperArray Bioscience Corp.). The levels of mRNA were standardized to the GAPDH housekeeping gene. The formula for the difference (ΔCT) between the amplified cytokine gene and the normalizer (GAPDH) was ΔCT = CT (cytokine)-ΔCT (GAPDH). The comparative ΔΔCT value between M. pulmonis and broth control mice was calculated with following formula: ΔΔCT = ΔCT (mycoplasma infection) – ΔCT (control). The formula for calculation of absolute comparative expression level was 2-ΔΔCT which showed the fold difference of cytokine mRNA between infected and uninfected mice.

Lymphocyte isolation, in vitro stimulation and cytokine assays

Mononuclear cells were isolated from lungs of infected or immunized mice and cultured as previously described [19-21]. Cells were cultured with or without 5-μg/ml mycoplasma Ag, and supernatants collected 4 days later. Levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, (Bio-Rad) and IL-17 (LINCOplex, Billerica, Millipore Corp, MA) were measured using a Bio-Plex 100 system (Bio-Rad).

Determination of gross lesions and mycoplasma numbers

Individual lung lobe scores were taken to generate the gross lesion index for lungs [22]. The number of mycoplasma colony forming units (CFU) in the lungs and nasal passages were determined [23].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the StatView software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Except for gross lesions, data were logarithmically transformed before statistical analysis and antilog of the means and standard errors (SEs) of transformed data were used to present the data. All experiments were performed at least twice.

RESULTS

Cytokine mRNA expression differs in the lungs of naïve wild-type BALB/c and cytokine-deficient mice

IFN-γ−/− mice are unable to clear mycoplasma infection and more susceptible to mycoplasma disease than either wild-type or IL-4−/− mice [15]. Nevertheless, IL-4, along with IFN-γ, can have a significant impact on immune regulation [24-26]. To examine the possibility that deficiency in either cytokine alters chemokine/cytokine expression patterns, subsequently influencing responses to infection, lungs were obtained from uninfected wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice, and microarrays were used to compare mRNA expression of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors.

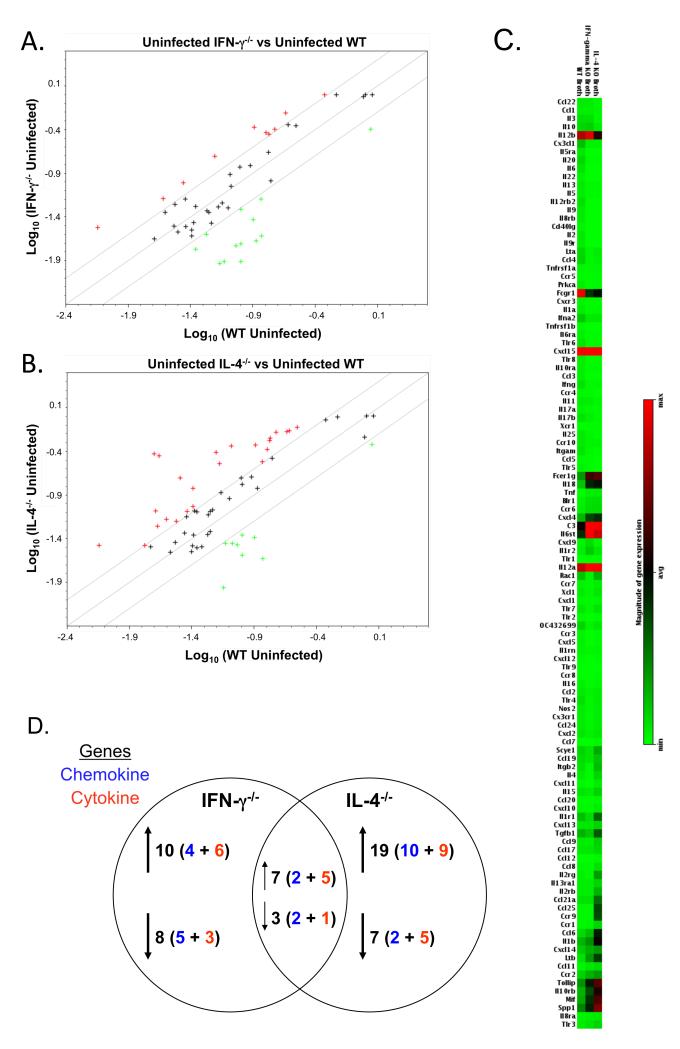

Pulmonary chemokine/cytokine mRNA expression patterns were unique between uninfected cytokine-deficient mice and wild-type mice (Figure 1). There was an indication that some Th2-type cytokines were expressed at higher levels in uninfected IFN-γ−/− mice, e.g. IL-4, CCL6, and CCL22, suggesting a slight increase in the resident Th2-type environment normally found in lung [27]. The down-regulated genes in the uninfected IFN-γ−/− mice included Th1-response associated chemokines, CXCL11 and CX3CL1. Thus, the loss of IFN-γ alters the pulmonary chemokine/cytokine mRNA expression pattern as compared to uninfected wild-type mice.

Figure 1. Cytokine mRNA expression differs in the lungs of uninfected wild-type and cytokine-deficient mice.

Lungs were obtained from broth-inoculated (uninfected) wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice. Total RNA was isolated from the lungs of individual mice. Equal amounts of RNA from individual mice (3 or 4 mice/experiment) from each experiment were pooled and used to probe membrane-based cDNA cytokine/chemokine microarrays. Data represent the average value of normalized spot intensities obtained from arrays from 2 different experiments. The results from the RNA obtained from the lungs of uninfected IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice were compared to the RNA obtained from the lungs of uninfected wild-type mice. Scatterplots represent gene expression in the lungs of (A) IFN-γ−/− versus wild-type mice and (B) IL-4−/− versus wild-type mice. A boundary of 2-fold change in either direction was selected. Green plus (+) signs located above the boundary line indicate an increase in gene expression, greater than boundary value, whereas red plus (+) signs below the boundary line indicate a decrease in gene expression. The further the sign is from the 2-fold boundary line, the greater the fold difference. Plus signs within the boundary lines mean the fold change were considered not significant. Each symbol represents one gene. (C) Relative gene expression was plotted as a gradient of colors from light green (minimum expression) to bright red (maximum expression) for the lungs of uninfected wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice. (D) Summary of number of genes changing in the lungs of uninfected IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice as compared to uninfected wild-type mice. Changes in gene expression are reported only if there was at least an average of ≥ 2-fold difference, with no value of ≤1.5 fold in either individual experiment. Chi square analysis was used to compare the distribution of gene expression changes between groups of mice. There was a significantly different change in the distribution gene expression between IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice (p ≤ 0.001).

There was a much bigger change in the pulmonary chemokine/cytokine mRNA profiles with IL-4 deficiency (Figure 1). Some Th1-associated chemokine/cytokine mRNAs were expressed at higher levels in IL-4−/− mice, e.g. IL-18, CXCL10, and CXCL11, suggesting a slight shift away from the normally Th2-type environment of the lung [27]. Down-regulated genes in uninfected IL-4−/− mice included IL-10, IL-13 and the pro-inflammatory chemokine/cytokine, CCL4 and IL-17a. Thus, a deficiency in either cytokine, particularly IL-4, results in a shift in the expression of a number of pulmonary chemokine/cytokine genes in uninfected mice, and this change in the normal cytokine network could contribute to differences in subsequent responses to mycoplasma infection or immunization. Importantly, there were only 10/45 chemokine/cytokine gene changes that were common between uninfected IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice (Figure 1d), supporting the broad, independent regulatory effects of these cytokines.

Cytokine-deficient mice display unique changes in pulmonary mRNA profiles after mycoplasma infection

By day 14 post-mycoplasma infection, IL-4−/− mice and wild-type mice have comparable mycoplasma numbers in the lungs, while IFN-γ−/− mice have a greatly impaired ability to control mycoplasma numbers in their lungs, corresponding to more severe disease [15]. To examine chemokine/cytokine responses occurring in IL-4−/−, IFN-γ−/− and wild-type mice, relative levels of pulmonary mRNA expression were compared between uninfected and mycoplasma-infected mice using microarrays.

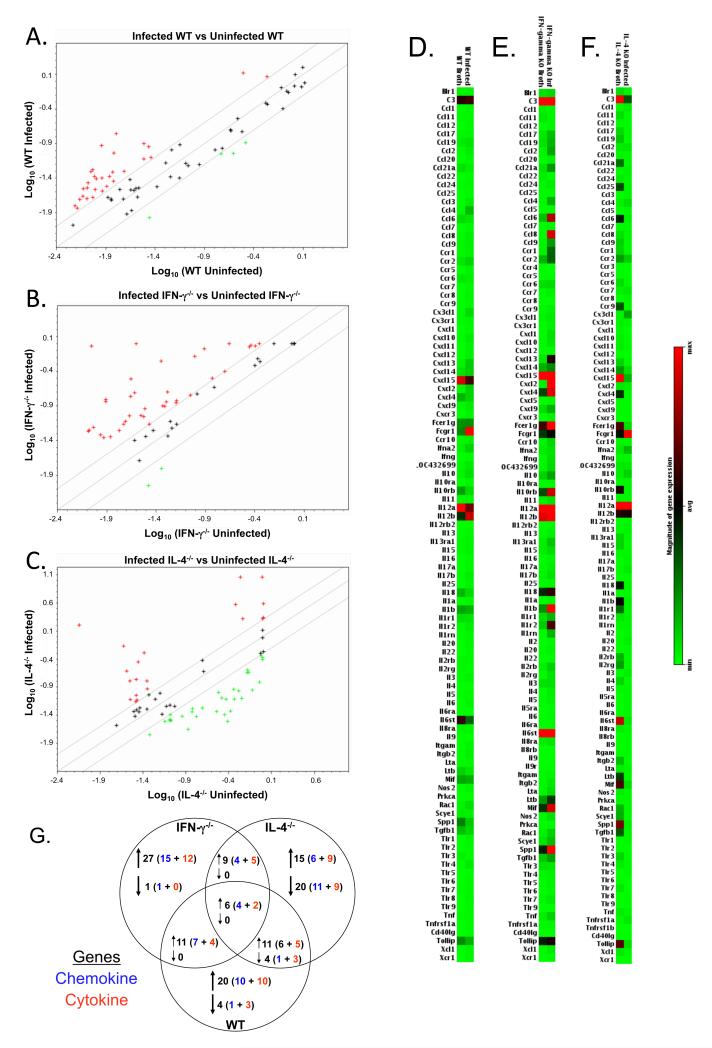

There was a unique pattern of cytokine/chemokine gene expression changes in lungs of infected mice. In all strains of mice, there were changes in chemokine/cytokine responses after infection (Figure 2a-f); however, there were only increases in 6 chemokine/cytokine mRNAs that were in common (Figure 2g). Each group of cytokine-deficient or wild-type mice had changes in expression of at least 24 chemokine/cytokine genes unique to the mouse strain. Both IFN-γ−/− mice and wild-type mice had increases in pro-inflammatory chemokines/cytokines, with some of the biggest increases found in IFN-γ−/− mice. Besides an up-regulation in several proinflammatory chemokines, infected IFN-γ−/− mice had high expression of the Th2 cytokine, IL-4 and Th2-cell attractant, CCL22 (Figure 2e, Table 1), indicating a shift in the type of responses. In IL-4−/− mice, there was an increase in some chemokines/cytokines, but in contrast to the other mouse strains, a striking number of genes showed a decreased expression in response to infection. For example, although IL-4−/− mice had increased mRNA expression of CCL2 mRNA post-mycoplasma infection, there was a decrease in the expression of 7 other CC type chemokines. Notably, mRNA levels of Th1 immune response mediating cytokines, i.e. IL-12a and IFN-γ were increased in IL-4−/− mice (Figure 2f, Table 1). Thus, the loss of a single cytokine resulted in significant shifts in a vast array of cytokine/chemokine mRNA expression in the lungs of cytokine-deficient mice.

Figure 2. Lungs of mycoplasma-infected cytokine-deficient mice have unique mRNA expression as compared to uninfected wild-type mice.

Lungs were obtained from broth-inoculated (uninfected) and mycoplasma-infected wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice, and RNA was isolated. Total RNA was isolated from the lungs of individual mice. Equal amounts of RNA from individual mice (3 or 4 mice/experiment) from each experiment were pooled and used to probe membrane-based cDNA cytokine/chemokine microarrays. Data represent the average value of normalized spot intensities obtained from arrays from 2 different experiments. The results from the RNA obtained from the lungs of mycoplasma-infected wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice were compared to the RNA obtained from the lungs of their respective uninfected counterparts. Scatterplots of gene expression in the lungs of (A) wild-type versus uninfected wild-type mice, (B) infected IFN-γ−/− versus uninfected IFN-γ−/− mice and (C) infected IL-4−/− versus uninfected IL-4−/− mice. A boundary of 2-fold change in either direction was selected. Green plus (+) signs located above the boundary line indicate an increase in gene expression, greater than boundary value, whereas red plus (+) signs below the boundary line indicate a decrease in gene expression. The further the sign is from the 2-fold boundary line, the greater the fold difference. Plus signs within the boundary lines mean the fold change were considered not significant. Each symbol represents one gene. Relative gene expression was plotted as a gradient of colors from light green (minimum expression) to bright red (maximum expression) for uninfected and mycoplasma-infected lungs of (D) IFN-γ−/−, (E) IL-4−/− and (F) wild-type mice. (G) Summary of number of genes changing in the lungs of uninfected IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice as compared to uninfected wild-type mice. Changes in gene expression are reported only if there was at least an average of ≥ 2-fold difference, with no value of ≤1.5 fold in either individual experiment. Chi square analysis was used to compare the distribution of gene expression changes between groups of mice. There was a significantly different change in the distribution gene expression between wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice (p ≤ 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Changes mRNA expression of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors in the lungs of wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice, after 14 days of mycoplasma infection

| Chemokine Genes |

mRNA changes after M. pulmonis infectiona |

Cytokine Genes | mRNA changes after M. pulmonis infectiona |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT mice | IFN-γ−/− mice | IL-4−/− mice | WT mice | IFN-γ−/− mice | IL-4−/− mice | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| fold increaseb |

fold decrease |

fold increase |

fold decrease |

fold increase |

fold decrease |

fold increaseb |

fold decrease |

fold increase |

fold decrease |

fold increase |

fold decrease |

||

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Ccl1 | 3.5 (2.4)c | Il1b | 4.6 (2.9) | 5.5 (0.1) | |||||||||

| Ccl2 | 4.6 (3.3) | 7.8 (0.2) | 4.8 (3.4) | Il3 | 2.3 (0.8) | ||||||||

| Ccl4 | 10.6 (10.2) | 12.6 (0.1) | 2.2 (6.2) | Il4 | 2.9 (1.9) | 6.9 (1.2) | N.D. | ||||||

| Ccl6 | 6.9 (2.8) | 5.6 (0.1) | Il5 | 2.3 (1.1) | |||||||||

| Ccl8 | 3.2 (1.3) | 104.9 (9.5) | 3.0 (0.1) | Il6st | 6.7 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Ccl9 | 8.1 (1.1) | 2.2 (0.3) | Il10 | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.3) | 2.0 (0.4) | |||||||

| Ccl11 | 2.9 (1.1) | Il12a | 3.8 (3.0) | ||||||||||

| Ccl17 | 2.7 (1.0) | Il12b | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.5 (2.0) | |||||||||

| Ccl19 | 2.9 (1.1) | 4.2 (4.0) | Il13 | 2.1 (2.0) | |||||||||

| Ccl21a | 3.8 (0.3) | 9.1 (1.0) | Il15 | 2.0 (5.2) | 8.1 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Ccl22 | 3.6 (2.0) | Il17a | 3.3 (3.9) | 3.2 (10.1) | |||||||||

| Ccl25 | 8.8 (0.2) | Il17b | 3.9 (1.6) | 2.3 (5.9) | 9.1 (5.5) | ||||||||

| Cxcl1 | 6.9 (1.5) | 2.7 (0.8) | Il18 | 3.4 (0.3) | 12.5 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Cxcl2 | 10.4 (9.3) | 39.7 (3.3) | Ifna2 | 3.4 (2.4) | 8.9 (7.7) | ||||||||

| Cxcl4 | 2 (0.2) | 2.6 (4.0) | 8.4 (1.1) | Ifng | 2.3 (1.2) | N.D. | 3.5 (2.0) | ||||||

| Cxcl5 | Tnf | 2.9 (3.4) | 2.7 (1.0) | ||||||||||

| Cxcl9 | 3.1 (0.02) | 2.3 (1.2) | 4.3 (2.0) | Tgfb1 | 26.5 (1.3) | ||||||||

| Cxcl10 | 6.0 (4.5) | 4.3 (1.1) | 2.4 (2.3) | Lta | 3.7 (3.1) | 2.2 (1.3) | |||||||

| Cxcl11 | 20.8 (17.7) | 2.3 (1.5) | Ltb | 3 (0.1) | 2.0 (1.8) | 7.5 (0.1) | |||||||

| Cxcl13 | 4.4 (3.0) | 12.5 (9.0) | 7.3 (0.1) | Mif | 2.3 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.3) | |||||||

| Cxcl14 | Itgb2 | 4.0 (3.7) | 3.8 (4.4) | 4.2 (0.1) | |||||||||

| Cxcl15 | 2.0 (0.1) | Spp1 | 3.1 (1.0) | 2.3 (0.1) | 8.3 (1.0) | ||||||||

| Cx3cl1 | 5.9 (5.0) | 28.4 (19.0) | Il1r1 | 2.3 (3.8) | 4.4 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Cx3cr1 | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.6 (0.5) | Il1 rn | 2.5 (1.4) | 11.8 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Ccr1 | 2.49 (1.8) | 13.9 (3.0) | 2.4 (1.0) | Il1r2 | 3.6 (1.2) | 6.7 (1.0) | |||||||

| Ccr2 | 2.1 (1.0) | Il2rb | 3.3 (7.3) | 4.6 (0.2) | |||||||||

| Ccr4 | 21.5 (15.7) | 4.1 (27.0) | Il2rg | 6.7 (7.9) | 6.3 (0.1) | ||||||||

| Ccr5 | 3.6 (5.0) | 2.2 (0.2) | Il10rb | 2.7 (0.1) | 2.5 (1.0) | 12.5 (3.0) | |||||||

| Ccr6 | 3.2 (0.5) | Il13ra1 | 3.7 (6.4) | ||||||||||

| Ccr7 | 3.5 (2.0) | Tnfrsf1 a | 2.6 (1.9) | 9.0 (3.0) | |||||||||

| Ccr9 | 2 (2.3) | 9.1 (0.1) | Tlr3 | 3.6 (0.3) | |||||||||

| Cxcr3 | 6.6 (7.3) | 4.4 (3.0) | Tlr4 | 5.5 (5.2) | |||||||||

| Fcer1g | 4.0 (0.3) | Tlr7 | 2.3 (1.6) | 3.2 (3.9) | 3.0 (0.2) | ||||||||

| Fcgr1 | 4.41 (3.1) | 5.5 (6.0) | |||||||||||

Wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice were either broth-inoculated (controls) or infected with mycoplasma and 14 days later, the lungs were obtained to isolate RNA.

Total RNA was isolated from the lungs of individual wild-type, IFN-γ−/− or IL-4−/− mice, and pooled RNA from each experiment (two experiments, total n= 3 and n=4) were used to probe membrane-based cDNA cytokine/chemokine microarrays.

Fold change of mRNA expression in response to infection. Fold increase was found by the ratio of normalized mRNA signal from infected/uninfected mice for each individual experiment; if the value of this ratio was < 1 then the reciprocal of that value was used to calculate the fold decrease. The data shown demonstrated at least an average of ≥ 2-fold change in two experiments with > 1.5 change obtained for any individual experiment. “N.D.” denotes signal was not detected.

Mean (SE) fold change of gene expression from two experiments

Real-time RT-PCR confirms IFN-γ and IL-4 have contrasting roles in regulating an array of responses against mycoplasma infection

Real-time RT-PCR was used to ascertain the changes reported by arrays. CCL4 [macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-1β)] CCL8 [monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP-2)], CCR5, CCL6, CXCL10 (IP-10), CXCR3, IL-10 and IL-17a mRNA levels were measured in samples collected from uninfected and infected lungs of wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice. The results from real-time RT-PCR strongly correlated with the data obtained from microarrays.

The expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines CCL4 and CCL8, which we previously proposed to participate in the recruitment of T cells via the receptor CCR5 [18], significantly increased in infected IFN-γ−/− mice as compared to infected IL-4−/− mice. Infected IL-4−/− mice, in fact, had a significant reduction in the mRNA expression levels of these chemokines (Figure 3). The mRNA levels of Th2-type immune response-associated chemokine CCL6 (known to be induced by IL-13) [28] increased in infected IFN-γ−/− mice compared to both infected wild-type and IL-4−/− mice, whereas its levels were decreased in infected IL-4−/− mice. There was also a greater increase in IL-10 and IL-17a mRNA levels in the lungs of infected IFN-γ−/− mice, as compared to infected wild-type and IL-4−/− mice. The lungs of the infected IL-4−/− mice, however, had enhanced CXCL10 (interferon-γ-induced-protein 10, IP-10) mRNA expression. Thus, the shift in cytokine/chemokine responses further demonstrates that IFN-γ and IL-4 have opposing roles in regulating an array of responses against mycoplasma infection.

Figure 3. mRNA levels of CCL4, CCL8, CCR5, CCL6, CXCL10, CXCR3, IL-10 and IL-17a in lungs of wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice after mycoplasma infection.

Wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice were either broth-inoculated (controls) or infected with mycoplasma, and 14 days later, RNA was isolated from the lungs of individual mice in two separate experiments. The transcripts of selected Th1/Th2 chemokines and cytokines were determined by real-time RT-PCR in RNA samples from individual mice. The vertical bars represent the means the standard error of the mean (SEM; n = 7 for each mouse strain) of the fold difference in mRNA levels of each of the genes relative to the average baseline values of samples from uninfected wild-type mice (control). Data were evaluated by ANOVA, followed by Fisher protected least square differences multigroup comparison. “*” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from broth-inoculated wild-type mice, “**” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from mycoplasma-infected wild-type mice, “•” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from broth-inoculated IFN-γ−/− mice, “••”denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from mycoplasma-infected IFN-γ−/− mice and “■” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from broth-inoculated IL-4−/− mice.

Mycoplasma-specific IL-5 responses in the lungs are higher in infected IFN-γ−/− mice

To characterize the T cell environment in mycoplasma-infected mice, total pulmonary lymphocytes were cultured in vitro with mycoplasma Ag. Levels of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-5 were determined in culture supernatants.

Lung lymphocytes from infected wild-type mice produced significant levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ in response to mycoplasma Ag (Figure 4). Although lung cells from each infected strain produced IL-5 in response to Ag, lymphocytes from infected IFN-γ−/− mice produced significantly higher IL-5 than the other mouse strains. Lung lymphocytes from IL-4−/− mice, on the other hand, produced significantly reduced levels of IL-5 as compared to both the wild-type and IFN-γ−/−mice. Hence, pulmonary immune responses in mycoplasma-infected IFN-γ−/− mice were consistent with an enhanced Th2-type (IL-5) response, while these responses were lower in IL-4−/− mice.

Fig. 4. Mycoplasma-specific cytokine production by cells isolated from the lungs and spleens of infected mice.

Mononuclear lymphocytes were isolated from the lungs of 14-day mycoplasma-infected wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice. Lung cells were cultured, in vitro, in the absence (grey bars) and presence (black bars) of mycoplasma antigen. Supernatants were collected 4 days later, and the levels of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-5 were determined using a Bio-plex suspension array. This experiment was done twice. The lowest detection level for the cytokines was 3.2 pg/ml. Detection was done in samples collected from a total of 7-8 mice/group. Data were evaluated by ANOVA, followed by Fisher protected least square differences multigroup comparison. “*” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between groups. “N.D.” denotes signal was not detected.

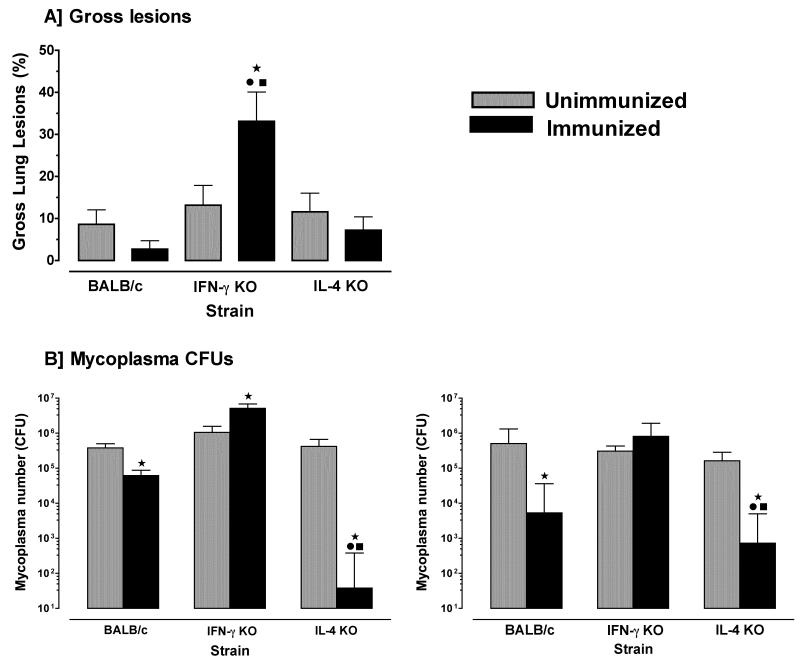

Immunization of IL-4−/− mice enhances protection from mycoplasma respiratory infection whereas immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice leads to higher numbers of mycoplasma and more severe disease

The above studies suggested IL-4−/− and IFN-γ−/− mice have altered pulmonary cytokine environments and have a unique response to infection. To determine whether immunization of wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice induces generation of mycoplasma-specific protection or immunopathology along the respiratory tract, mice were nasal-pulmonary immunized with mycoplasma Ag and 7 days after the second immunization, all mice were infected. On day 14 post-infection, gross pulmonary lesions and mycoplasma numbers in lungs and nasal washes were determined.

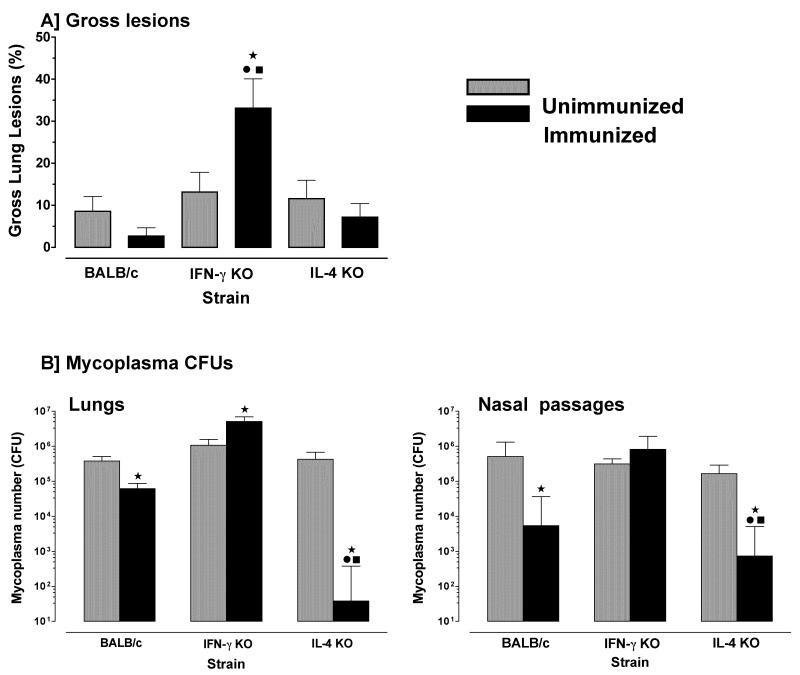

Surprisingly, there was a significant increase in gross lesions in the lungs of immunized IFN-γ−/− mice after infection, as compared to infected unimmunized IFN-γ−/−, IL-4−/− or wild-type mice (Figure 5a). Furthermore, mycoplasma numbers in lungs of immunized IFN-γ−/− mice were significantly (1-log) higher than unimmunized IFN-γ−/− mice (Figure 5b); whereas immunized wild-type mice had more than half a log reduction in mycoplasma numbers in lungs, as compared to unimmunized mice. Most interestingly, immunized IL-4−/− mice had a 4-log decrease in mycoplasma numbers in lungs. Immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice did not affect mycoplasma numbers within the upper respiratory tract, but immunized IL-4−/− and wild-type mice had significantly lower numbers of mycoplasma recovered from nasal passages with the numbers lowest in nasal passages of IL-4−/− mice. Thus, immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice exacerbated, rather than reduced, mycoplasma disease and infection, whereas immunization of IL-4−/− mice significantly enhanced protection in both upper and lower respiratory tracts.

Figure 5. Immunization of IL4−/− mice confers better protection in lungs and nasal passages to mycoplasma infection.

Mice were immunized with mycoplasma membrane antigen once (day 1) and again 7 days later. Immunized and PBS-inoculated (control) mice from each of the wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice were infected with mycoplasma and 14 days later, lungs were obtained to score the (A) lesion indices, and (B) the numbers of mycoplasma CFUs were determined in lungs and nasal passages. Control mice (grey bar) were not immunized. Immunized mice (black bar) were nasal-pulmonary immunized with mycoplasma antigen alone. This experiment was done twice. Vertical bars and error bars represent mean ×/÷ SE (total n=6). Data were evaluated by ANOVA, followed by Fisher protected least square differences multigroup comparison. “*” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from PBS inoculated wild-type mice, “•” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from PBS inoculated IFN-γ−/− mice and “■” denotes significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) from PBS inoculated IL-4−/− mice.

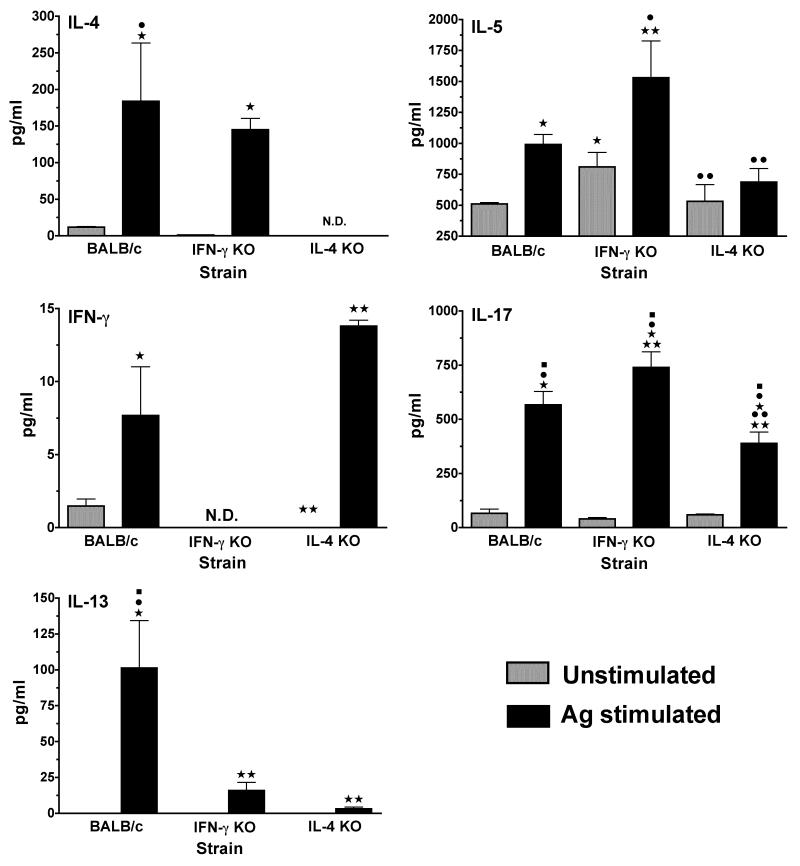

Mycoplasma-specific IL-5 and IL-17 responses in the lungs are greater in immunized IFN-γ−/− mice

Mycoplasma-specific cytokine responses generated after immunization were determined in wild-type and cytokine-deficient mice. Pulmonary lymphocytes, isolated 7 days after the second immunization, were cultured in vitro with mycoplasma Ag. Levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-17 in cultures supernatants were analyzed.

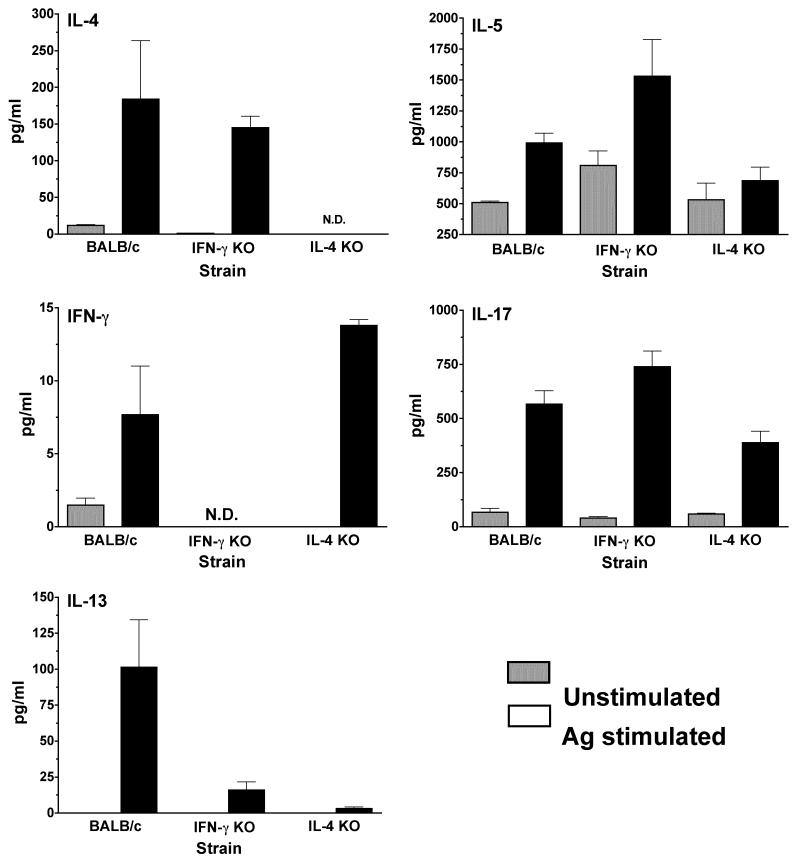

Lung lymphocytes isolated from immunized wild-type mice produced significant levels of IL-4 and IFN-γ in responses to mycoplasma Ag (Figure 6). Lung cells from immunized IFN-γ−/− mice produced higher levels of the IL-5 and IL-17, as well as IL-4, than immunized IL-4−/− mice, while IL-4−/− mice produced higher levels IFN-γ. Similar to infected mice, these data are consistent with preferential increases in mycoplasma-specific Th2- and Th17-type responses in the lungs of immunized IFN-γ−/− mice and Th1 type responses in the lungs of immunized IL-4−/− mice.

Figure 6. Mycoplasma-specific cytokine production by cells isolated from the lungs of immunized mice.

Mononuclear lymphocytes from the lungs were isolated on day 14, following nasal-pulmonary immunizations of wild-type, IFN-γ−/− and IL-4−/− mice. Pooled lung lymphoid cells from 4 mice/group were cultured, in vitro, in the absence (grey bars) and presence (black bars) of mycoplasma antigen. Supernatants were collected 4 days later, and the levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-17 were determined using a suspension array. The lowest detection level for the cytokines was 3.2 pg/ml. Detection was done in samples collected from 2 separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Immune responses against mycoplasma cannot only protect from disease, but also contribute to pathology, complicating development of vaccines [4-6, 29]. Thus, it is critical to understand the regulatory mechanisms determining resistance and immunopathology against mycoplasma respiratory diseases. Although we know Th cell responses are involved [9, 30], the mechanisms involved in immunopathology and protective immunity are unknown. The present study examined the impact of Th-polarizing cytokines, IFN-γ and IL-4, on the chemokine/cytokine responses after infection and their contribution to protective adaptive immunity in response to nasal-pulmonary immunization against mycoplasma.

The deficiency in a single cytokine, either IFN-γ or IL-4, resulted in a significant shift in pulmonary cytokine/chemokine gene expression before and after infection. The effects were most obvious in IL-4−/− mice since changes in chemokine/cytokine mRNA expression were more extensive than in lungs of IFN-γ−/− mice. The lung environments of naïve wild-type mice are typically Th2-type [27]; however, the lungs of naïve IL-4−/− mice had increased expression of several chemokine/cytokine mRNAs associated with Th1-type responses, suggesting a shift away from the normally Th2-dominant lung environment. Consequently, the patterns of chemokine/cytokine mRNA profiles in the lungs of IL-4−/− mice were significantly altered 14 days post-mycoplasma infection, despite subtle differences in disease susceptibility compared to wild-type mice. The loss of IFN-γ also impacted lung chemokine/cytokine mRNA profiles of naïve and infected mice. Infected IFN-γ−/− mice developed more severe disease and despite similar numbers of chemokine/cytokine mRNAs changes, their pattern of the gene expression was altered from that in wild-type mice. Our previous study found 14 day-infected IFN-γ−/− mice had fewer lymphocytes and macrophages in lungs than wild-type or IL-4−/− mice [15]. It is possible that other cell populations, such as neutrophils or eosinophils were increased, but these were not examined. In any case, this does demonstrate a change in cellular responses to infection in IFN-γ−/− mice. Thus, the loss of IFN-γ or IL-4 altered the expression of a wide array of cytokines/chemokines mRNAs in lungs in naïve mice that may subsequently influence the responses after immunization.

IFN-γ plays a critical role in not only pathogenesis of mycoplasma disease, but also in the generation of adaptive immune responses conferring resistance to infection. The loss of IFN-γ impairs innate immune mechanisms in controlling numbers of mycoplasmas in the lungs [31]. Immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice led to a significant increase in disease severity along with an impaired ability to clear mycoplasma from respiratory tract, while immunized wild-type mice showed increased protection characterized by less disease severity and lower mycoplasma numbers. These results are consistent with those obtained for other respiratory infections, such as mycobacteria [32]. In addition, pulmonary immune responses in infected or immunized IFN-γ−/− mice were consistent with the development of enhanced Th2-type responses, as mycoplasma-specific IL-5 production was higher by lymphocytes from IFN-γ−/− mice. In addition, infected IFN-γ−/− mice had decreased expression of IL-12 mRNA. IFN-γ receptor−/− or IFN-γ−/− mice have similar shifts towards Th2-type responses in lung after other lung infections [26, 32, 33]. Interestingly, nasal-pulmonary immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice also resulted in higher IL-17 responses. A recent study in our lab [34] demonstrated a deficiency in IL-17 receptor results in increased susceptibility to mycoplasma. Also, studies by Wu, et. al. [35] established a crucial role of IL-23 induced IL-17 in an acute M. pneumoniae lung infection. However, enhanced IL-17, in this study, corresponded to higher disease severity in the IFN-γ−/− mice, suggesting that in some situations IL-17 may contribute to inflammatory lesions during persistent mycoplasma infections. Thus, the lack of IFN-γ eliminates development of protective immunity, resulting in exacerbation of mycoplasma disease due to immunization. These results demonstrate IFN-γ is critical in developing beneficial adaptive immune responses against mycoplasma, and the predominance of Th2-type responses after immunization of IFN-γ−/− mice indicate that Th2 responses are involved in development of inflammatory lesions.

Loss of IL-4 had essentially an opposite effect on generation of protective immunity and mycoplasma pathogenesis. Immunization of the IL-4−/− mice led to better clearance of mycoplasma both in the upper and lower respiratory tracts and developed less severe disease than IFN-γ−/− mice. The loss of IL-4, similarly, has minimal but significant effect on mycobacterial disease pathogenesis [36-38]. Despite the apparent subtle effect on disease pathogenesis, the pattern of chemokine/cytokine mRNA profiles in the lungs of IL-4−/− mice was significantly affected. The fact that a few chemokine/cytokine genes associated with Th1-type immune responses were amongst the mRNAs with higher expression in lungs of IL-4−/− mice suggests a shift away from the normally Th2-dominant lung environment. In support, pulmonary lymphocytes from immunized or infected IL-4−/− mice produced significantly lower levels of IL-5 and IL-17 in response to mycoplasma Ag. It is likely that the altered resistance against mycoplasma infection after immunization is a result of effects on Th cells since our recent study [30] demonstrates that CD4+ T cells, not CD8+ T cells, from immunized mice can confer resistance to mycoplasma infection. Thus, IL-4 responses dampen the development of mycoplasma-specific resistance after nasal pulmonary immunization, further suggesting that Th1-type responses mediate resistance.

Development of mycoplasma vaccines is problematic, often exhibiting only variable success and in some cases, more severe immunoreactivity [29]. Importantly, there appears to be a complex balance between beneficial and detrimental adaptive host responses. An understanding of the mechanisms involved in modulating these responses is critical for vaccine development. To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the critical role played by the Th1 and Th2-response polarizing cytokines, IFN-γ and IL-4, during the development of protective adaptive immunity against mycoplasma respiratory disease. The results clearly demonstrate there are two contrasting adaptive immune responses that influence the outcome of immunization and infection. The loss of IFN-γ revealed detrimental responses promoting immunopathology after infection, also leading to adverse reactions post-immunization. Thus, IFN-γ mediated responses were shown to contribute to the success of nasal-pulmonary immunization against mycoplasma disease, while IL-4 responses interfered with optimal development of protective adaptive immune responses. Based on our previous work [12, 18, 30], these results support our ongoing hypothesis that different Th cell populations are responsible in determining the balance between protective and detrimental immune responses against mycoplasma. The current study demonstrates that IL-4 and IFN-γ have opposing roles and exhibit broad effects on host responses mycoplasma infection. Based on these results, optimal vaccination against mycoplasma disease appears to be dependent on promoting protective IFN-γ-dependent, perhaps Th1 responses, while minimizing the impact of IL-4-mediated responses that dampen generation of protective immunity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Rance Berg for his useful discussions and support.

Footnotes

The authors do not have a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Sheetal Bodhankar, Xiangle Sun, Matthew D. Woolard and Jerry W. Simecka: No conflict

Part of the information in this manuscript was presented at the International Organization of Mycoplasmology Congress in Tianjin, China in July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freymuth F, Vabret A, Brouard J, et al. Detection of viral, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in exacerbations of asthma in children. J Clin Virol. 1999;13:131–9. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(99)00030-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin RJ, Chu HW, Honour JM, Harbeck RJ. Airway inflammation and bronchial hyperresponsiveness after Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a murine model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:577–82. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.5.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassell GH, Lindsey JR, Overcash RG, Baker HJ. Murine mycoplasma respiratory disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1973;225:395–412. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor G, Taylor-Robinson D, Fernald GW. Reduction of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced pneumonia in hamsters by immunosuppressive treatment with antithymocyte sera. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1974;7:343. doi: 10.1099/00222615-7-3-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartner SC, Lindsey JR, Gibbs-Erwin J, Cassell GH, Simecka JW. Roles of innate and adaptive immunity in respiratory mycoplasmosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3485–91. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3485-3491.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keystone EC, Taylor-Robinson D, Osborn MF, Ling L, Pope C, Fornasier V. Effect of T-cell deficiency on the chronicity of arthritis induced in mice by Mycoplasma pulmonis. Infection and Immunity. 1980;27:192–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.1.192-196.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassell GH, Davis JK. Protective effect of vaccination against Mycoplasma pulmonis respiratory disease in rats. Infect Immun. 1978;21:69–75. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.1.69-75.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodge LM, Simecka JW. Role of upper and lower respiratory tract immunity in resistance to Mycoplasma respiratory disease. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:290–4. doi: 10.1086/341280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones HP, Tabor L, Sun X, Woolard MD, Simecka JW. Depletion of CD8+ T cells exacerbates CD4+ Th cell-associated inflammatory lesions during murine mycoplasma respiratory disease. J Immunol. 2002;168:3493–501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodhankar S, Woolard MD, Sun X, Simecka JW. NK cells interfere with the generation of resistance against mycoplasma respiratory infection following nasal-pulmonary immunization. J Immunol. 2009;183:2622–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Infante-Duarte C, Kamradt T. Th1/Th2 balance in infection. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:317–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00812260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones H, Tabor L, Sun X, Woolard M, Simecka J. Depletion of CD8+ T cells exacerbates CD4+ Th cell associated inflammatory lesions during murine mycoplasma respiratory disease. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168:3493–3501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renauld JC. New insights into the role of cytokines in asthma. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:577–89. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.8.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Peng SL, Glimcher LH. Molecular mechanisms regulating Th1 immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:713–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolard MD, Hodge LM, Jones HP, Schoeb TR, Simecka JW. The upper and lower respiratory tracts differ in their requirement of IFN-gamma and IL-4 in controlling respiratory mycoplasma infection and disease. J Immunol. 2004;172:6875–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson MK, Davis JK, Lindsey JR, Cassell GH. Clearance of different strains of Mycoplasma pulmonis from the respiratory tract of C3H/HeN mice. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2163–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2163-2168.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simecka JW, Cassell GH. Serum antibody and cellular responses in LEW and F344 rats after immunization with Mycoplasma pulmonis antigens. Infect Immun. 1987;55:731–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.3.731-735.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun X, Jones HP, Hodge LM, Simecka JW. Cytokine and chemokine transcription profile during Mycoplasma pulmonis infection in susceptible and resistant strains of mice: macrophage inflammatory protein 1beta (CCL4) and monocyte chemoattractant protein 2 (CCL8) and accumulation of CCR5+ Th cells. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5943–54. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00082-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haas H, Falcone FH, Holland MJ, et al. Early interleukin-4: its role in the switch towards a Th2 response and IgE-mediated allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;119:86–94. doi: 10.1159/000024182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okahashi N, Yamamoto M, Vancott JL, et al. Oral immunization of interleukin-4 (IL-4) knockout mice with a recombinant Salmonella strain or cholera toxin reveals that CD4+ Th2 cells producing IL-6 and IL-10 are associated with mucosal immunoglobulin A responses. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1516–25. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1516-1525.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taguchi T, Aicher WK, Fujihashi K, et al. Novel function for intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Murine CD3+, gamma/delta TCR+ T cells produce IFN-gamma and IL-5. J Immunol. 1991;147:3736–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overcash RG, Lindsey JR, Cassel GH, Baker HJ. Enhancement of natural and experimental respiratory mycoplasmosis in rats by hexamethylphosphoramide. Am J Pathol. 1976;82:171–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simecka JW, Thorp RB, Cassell GH. Dendritic cells are present in the alveolar region of lungs from specific pathogen-free rats. Reg Immunol. 1992;4:18–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajewski TF, Fitch FW. Anti-proliferative effect of IFN-gamma in immune regulation. I. IFN-gamma inhibits the proliferation of Th2 but not Th1 murine helper T lymphocyte clones. J Immunol. 1988;140:4245–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chensue SW, Warmington KS, Ruth J, Lincoln PM, Kunkel SL. Cross-regulatory role of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma), IL-4 and IL-10 in schistosome egg granuloma formation: in vivo regulation of Th activity and inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98:395–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb05503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohlleben G, Erb KJ. The absence of IFN-gamma leads to increased Th2 responses after influenza A virus infection characterized by an increase in CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells producing IL-4 or IL-5 in the lung. Immunol Lett. 2004;95:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones H, Hodge L, Fujihashi K, Kiyono H, McGhee JR, Simecka JW. The pulmonary environment promotes Th2 cell responses after nasal-pulmonary immunization with antigen alone, but Th1 responses are induced during instances of intense immune stimulation. J. Immunol. 2001;167:4518–4526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma B, Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Gerard C, Strieter R, Elias JA. The C10/CCL6 chemokine and CCR1 play critical roles in the pathogenesis of IL-13-induced inflammation and remodeling. J Immunol. 2004;172:1872–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cimolai N, Cheong AC, Morrison BJ, Taylor GP. Mycoplasma pneumoniae reinfection and vaccination: protective oral vaccination and harmful immunoreactivity after re-infection and parenteral immunization. Vaccine. 1996;14:1479–83. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodhankar S. NK cells interfere with the generation of resistance against mycoplasma respiratory infection following nasal-pulmonary immunization. Journal of Immunology. 2009 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolard MD, Hudig D, Tabor L, Ivey JA, Simecka JW. NK cells in gamma-interferon-deficient mice suppress lung innate immunity against Mycoplasma spp. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6742–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6742-6751.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ordway D, Henao-Tamayo M, Smith E, et al. Animal model of Mycobacterium abscessus lung infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1502–11. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1007696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boelen A, Kwakkel J, Barends M, de Rond L, Dormans J, Kimman T. Effect of lack of Interleukin-4, Interleukin-12, Interleukin-18, or the Interferon-gamma receptor on virus replication, cytokine response, and lung pathology during respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J Med Virol. 2002;66:552–60. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieve AN, Meeks KD, Bodhankar S, et al. A novel IL-17-dependent mechanism of cross protection: respiratory infection with mycoplasma protects against a secondary listeria infection. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:426–38. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Q, Martin RJ, Rino JG, Breed R, Torres RM, Chu HW. IL-23-dependent IL-17 production is essential in neutrophil recruitment and activity in mouse lung defense against respiratory Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.North RJ. Mice incapable of making IL-4 or IL-10 display normal resistance to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:55–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hernandez-Pando R, Aguilar D, Hernandez ML, Orozco H, Rook G. Pulmonary tuberculosis in BALB/c mice with non-functional IL-4 genes: changes in the inflammatory effects of TNF-alpha and in the regulation of fibrosis. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:174–83. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buccheri S, Reljic R, Caccamo N, et al. IL-4 depletion enhances host resistance and passive IgA protection against tuberculosis infection in BALB/c mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:729–37. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]