Abstract

Background

Multiple studies demonstrate decreases in striatal D2-like (D2, D3) radioligand binding in primary focal dystonias. Although most investigations have focused on D2 specific receptors (D2R), a recent study suggests that the decreased D2-like binding may be due to a D3 specific (D3R) abnormality. However, only limited data exist on the role of D1 specific receptors (D1R) and the D1R-mediated pathways within basal ganglia in dystonia. Metabolic PET data in primary generalized dystonia suggest resting state overactivity in the D1R-mediated "direct" pathway leading to excessive disinhibition of motor cortical areas. This work investigated whether striatal D1-like receptors are affected in primary focal dystonias.

Methods

We measured striatal (caudate and putamen) specific binding of the D1-like radioligand [11C] NNC 112 using PET in 19 patients with primary focal dystonia (cranial, cervical or arm) and 18 controls.

Results

We did not detect a statistically significant difference in striatal D1-like binding between the two groups. This study had 91% power to detect a 20% difference, making a false negative study unlikely.

Conclusions

Since [11C] NNC112 has a high affinity for D1-like receptors, very low affinity for D2-like receptors and minimal sensitivity to endogenous dopamine levels, we conclude that D1-like receptor binding is not impaired in these primary focal dystonias.

Keywords: PET, focal dystonia, D1 receptor, [11C] NNC 112

Introduction

Dystonia is a disabling involuntary movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements, postures, or both.1 Multiple lines of evidence in human and animal models demonstrate abnormal dopaminergic systems in dystonia. Dystonia can be an initial manifestation in Parkinson disease (PD) that may respond to L-dopa2,3 or can be a side effect of L-dopa treatment in PD.4 Hereditary dystonias due to defects in dopamine synthesis respond to L-dopa.5 D5 specific receptor (D5R) alterations may result from a susceptibility gene for cervical dystonia.6 Further, animal models of various genetic dystonias indicate involvement of dopaminergic pathways. The TOR1A mouse model of childhood onset generalized dystonia has impaired dopamine release.7 D2 R availability is reduced in the DYT11 mouse model of myoclonus dystonia.8

Between the two classes of dopamine receptors (D1-like and D2-like), most studies have investigated the role of D2-like family (D2, D3, D4) receptors. In contrast the role of D1-like family (D1, D5) receptors remains largely unknown.

Molecular neuroimaging has provided important insights into the role of dopaminergic pathways in people with dystonia. Several neuroimaging studies reported decreased D2-like radioligand binding in primary dystonias.9,10 Most studies have focused on striatal D2R10,11 with the assumption that striatal concentrations of D3R and D4R are negligible. However we recently demonstrated lack of decrease in striatal binding of the highly D2R specific radioligand N-([18F]Methyl) benperidol [18F]NMB in adult onset focal dystonia.12 This finding in conjunction with the recent report that D3R concentration in human caudate and putamen is much higher than previously assumed13 suggests that dystonia may be associated with a reduction in striatal D3R. Conversely, there are only limited data on the role of D1R and D1R mediated direct pathway in dystonia. One report did not find any change in striatal D1-like receptors in humans with dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD).14 However, a metabolic PET study showed resting state overactivity in the lentiform nucleus15, which may reflect increased input to this region. These data have been interpreted as increased activity in the D1R mediated "direct" pathway from the striatum to the GPi, leading to excessive inhibition of the GPi and excessive disinhibition of motor cortical areas that could contribute to the clinical manifestations of dystonia.

In this study we quantified striatal uptake of the D1-like specific radioligand [11C]NNC 112 in patients with adult onset focal dystonias to further characterize role of D1-like receptors in this patient population.

Methods

Subjects

Nineteen subjects with primary cervical, cranial or arm dystonia (age: 58±10; 9 women and 10 men) were recruited from the Movement Disorder Center at Washington University in St. Louis.16 Only patients who could hold their head still when lying down were enrolled in the study. Eighteen healthy controls (age: 56± 8; 13 women and 5 men) were enrolled as well. All subjects underwent a complete history and neurological examination to exclude secondary dystonias or concomitant neurological disorder. No one had prior exposure to reserpine, tetrabenazine, dopamine antagonists, or amphetamines. Three subjects had exposure to L-dopa for less than two months after the initial diagnosis but not within the last year prior to imaging. All but two dystonic subjects had received botulinum toxin within the last 3 months. Only one dystonic and one healthy control subject reported a history of smoking. All subjects had Mini-Mental Status examinations.17 These studies were approved by the Washington Human Research Protection Office and the Radioactive Drug and Research Committee. Each participant provided written informed consent.

Radiopharmaceutical preparation

[11C]NNC 112 ([11C](+)-8-chloro-5-(7-benzofuranyl)-7-hydroxy-3-methyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepine) was prepared by [11C]methylation of (+)-N-desmethyl NNC 112 (provided by the NIMH Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program) using modification of previously-reported procedures.18 Carbon-11 was produced as 11CO2 using the Washington University JSW BC 16/8 cyclotron and the 14N(p,α)11C nuclear reaction. The 11CO2 was converted to 11CH3I using the microprocessor-controlled PETtrace MeI MicroLab (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI), and immediately used for [11C]methylation of (S)-O-desmethy NNC 112. Product [11C] NNC 112 was purified via semipreparative HPLC, and reformulated in a 10% ethanol/ normal saline solution. The radiochemical purity exceeded 95%, and the specific activity exceeded 1200 Ci/mmol (44.4 TBq/mmol), as determined by analytical HPLC. The mass of NNC 112 was ≤ 6.5 µg per injected dose.

MRI procedure

All subjects had a brain magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE)19 on a 3.0T Siemens Trio scanner using a twelve channel head coil. MP-RAGE is a T1-weighted MRI which offers high contrast to noise structural MR images required for defining volumes of interest (VOI).20 A two-tailed unpaired t-test was applied to compare the volumes of the VOIs used for cerebellum, caudate and putamen between two groups with the alpha level of 0.05.

PET procedure

PET studies were performed using a Siemens/CTI ECAT HR plus in 3D mode. We placed a 20 gauge plastic catheter in an antecubital vein for radioligand injection. Each subject was positioned in the PET scanner using cross laser lines, and a polyform mask (Roylan Industries, Menomenee Falls, WI) helped reduce head movement during the scan. We also videotaped the head to detect movement of the head or face during the PET. A rotating [68Ge] rod source was used to collect a transmission scan to measure individual attenuation factors. After a bolus (40 sec) intravenous injection of [11C] NNC112 (8–20 mCi; 296–740 MBq), we collected a 90 minute dynamic acquisition in 27 sequential frames (6 frames each 30 sec, 3 frames each 1 min, 2 frames each 2 min, 16 frames each 5 min). The emission scan was reconstructed with corrections for attenuation, randoms and scatter yielding a transaxial and axial spatial resolution of 4.6 mm and 4.1 mm full width half maximum, respectively.

PET Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in a blinded fashion. Review of the video recordings during the scan did not reveal any visible head motion.

Dynamic PET images were realigned using automatic image registration (AIR),21 so that slow head drift was corrected by aligning the frames. The total drift in any axis did not exceed 10 mm. Volumes of interest (VOIs) were manually drawn on the MP-RAGE for the caudate, putamen and cerebellum following the outline of the anatomical structures for each subject individually in the native space. The MP-RAGE from each subject then was co-registered to the aligned PET image. A summed PET image (frames 2–27) was used for this step. These VOIs were transformed into PET coordinates using the transformation matrices for the MRI to PET co-registration.22 Partial volume effects (PVE) correction was performed using a method that estimates the gray-matter activity in each VOI.23,24 A decay corrected tissue activity curve for each VOIs was extracted from the PET data and analyzed by Logan graphical method using a cerebellar region as the reference to calculate the non-displaceable binding potential (BPND).25 We set the start of linearity at 15 min based on numerous animal and human NNC 112 PET data that were acquired preceding this study.

A two-tailed unpaired t-test was applied to compare the regional values of BPND and age between healthy controls and subjects with focal dystonia. We used ANCOVA to determine the effect of age and sex and their interaction on putamen and caudate BPND in healthy controls. GPower 3.1 (www.g-power.de) was used for post-hoc analysis of achieved power. This study had 91% power to detect 20% difference between the two groups with an alpha level of 0.05.

Voxelwise whole brain analysis

We used Ichise’s multilinear reference tissue model (MRTM) for voxelwise binding potential analysis.26 The PET images were registered to MPRAGE data using the vector gradient method. Atlas registration was made using 12-degree-of-freedom affine transformation via MPRAGE using in-house software.27 BPND map for each subject was then transformed to the atlas space for further analysis. We used SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk) to perform a t-test between controls and dystonic subjects using a Family Wise Error (FWE) rate of 0.05 to correct for multiple comparisons.

Results

Age distribution of healthy controls (M=56, SD=8) did not significantly differ from dystonic subjects (M=58, SD=10), t(35)=0.57, p=0.58. Similarly, sex distribution did not differ significantly between the two groups t(35)=1.55, p=0.13. All participants scored higher than 28 in MMSE. The Table has further characteristics of the dystonia group.

Table.

Summary of participants’ clinical characteristics

| Characteristics of participants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Control | Dystonic | |

| N | 18 | 19 |

| Mean age (yr) | 56±8 | 58±10 |

| Gender | 13 F; 6 M | 9 F; 10 M |

| Smoker | 1 | 1 |

| Right handedness | 18 | 18 |

| Family history of dystonia | N/A | 2 (father and son) |

| Treated with botulinum toxin within the last 3 months | N/A | 18 |

| Cranial dystonia | N/A | 8 (6 pure blepharospasm) |

| Hand dystonia | N/A | 7 |

| Cervical dystonia | N/A | 4 |

| Pure writing cramp | N/A | 0 |

| Median duration of dystonia (yr) | N/A | 12 |

| MMSE score | ≥28 | ≥28 |

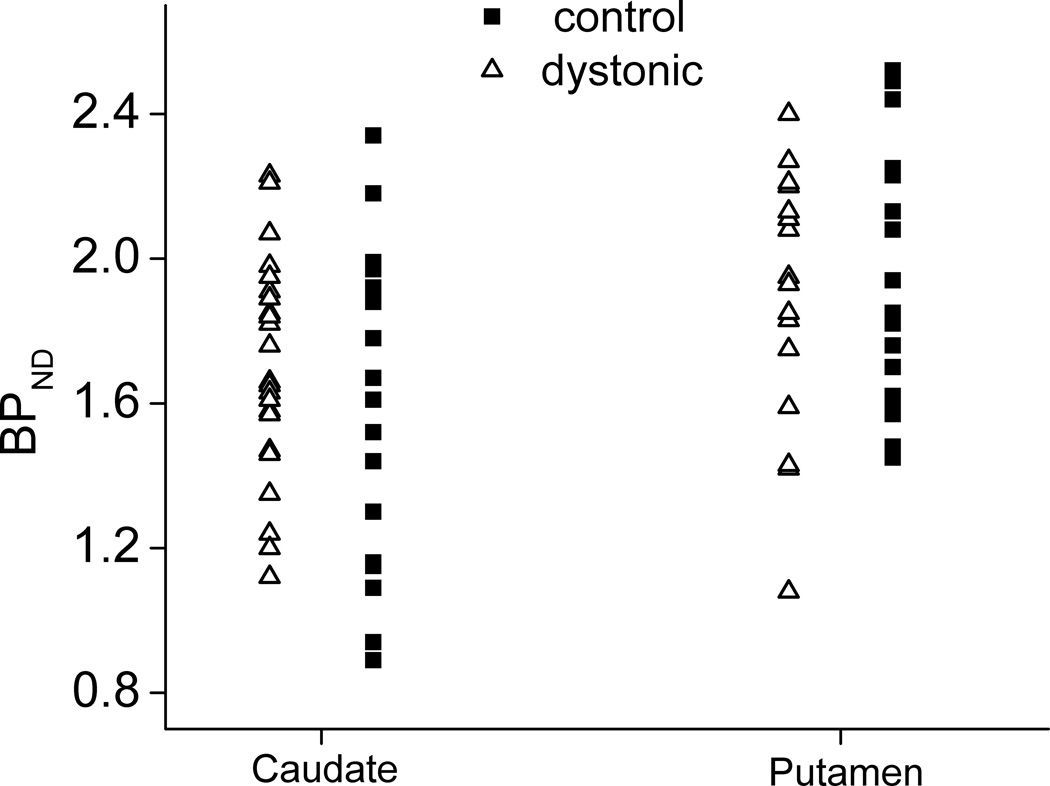

Putamenal binding potential (BPND), a measure of specific binding, did not differ between healthy (M=1.97, SD=0.34) and dystonic subjects (M=1.87, SD=0.35), t(35)= 0.857, p=0.40. Similarly caudate BPND did not significantly differ between healthy (M=1.60, SD=0.44) and dystonic subjects (M=1.64, SD=0.31), t(35)=0.364, p=0.069 (Figure). An ANCOVA indicated no main effect of sex (F (1, 15)=2.07, p=0.17, or age (F (1, 15)=0.006, p=0.94) on putamenal BPND but did reveal a significant interaction between sex and age (F (1, 15)=7.64, p=0.01) in healthy controls. There was no main effect of sex (F (1, 15)=1.90, p=0.19) or age (F(1, 15)=0.02, p=0.89) and no interaction between sex and age (F (1, 15)=3.74, p=0.07) on caudate BPNDin healthy controls.

Figure.

There is no statistically significant difference between healthy subjects and those with focal dystonia in [11C]NNC 112 BPND of caudate or putamen.

There was no statistically significant difference between the volumes used for cerebellum, caudate or putamen between the dystonic subjects and healthy controls (p> 0.91 for all measures).

The whole brain voxelwise analysis did not identify any statistically significant differences in the NNC112 BPND between the controls and dystonics.

Discussion

We did not detect a statistically significant difference in striatal (putamen or caudate) uptake of the D1-like radioligand [11C] NNC 112 in people with primary focal dystonia (arm, cervical or cranial). This study was designed with a high power (91%) to detect at least a 20% difference between dystonics and controls making a false negative study unlikely. Since [11C] NNC112 has a high affinity for binding to D1-like receptors with very low affinity to D2-like receptors and is not sensitive to endogenous dopamine levels28,29 we conclude that striatal D1-like specific binding is not impaired in primary focal dystonias. Despite strong evidence of association between primary dystonia and a defect in dopaminergic mediated pathways, neither D1-like nor D2R seems to be altered.12

Nevertheless, lack of an abnormality in D1-like or D2R binding does not exclude involvement of D1R or D2R mediated pathways in the pathophysiology of primary dystonia. Alternatively changes in cholinergic striatal interneurons could alter dopaminergic mediated basal ganglia circuits.30 Clinical evidence of symptomatic response to anticholinergics for dystonic symptoms supports this hypothesis. DYT1 mouse models have abnormalities in the cholinergic system.31–33 Furthermore, striatal cholinergic density may be decreased in cervical dystonia.34 Specific radioligands are available for PET studies of acetylcholine receptors (FP-TZTP for muscarinic type, 2-FA-85380 for nicotinic type) and specific PET radioligands for acetylcholine transporters may soon be available for human studies.35

Furthermore, D3R have not yet been measured in primary focal dystonia and could be involved in dopaminergic synaptic regulation by influencing extracellular dopamine level via regulation of membranous dopamine transporter (DAT), by effects on auto-regulation or by synergistic interaction with D1R.36–39 [11C]PHNO is currently used for investigation of D3R mainly in regions with relatively high D3R concentration since this agonist radioligand has poor selectivity for D2R versus D3R dopamine receptors.40 Given the lower concentration of D3R compared to D2R in striatum it is not an ideal candidate for examining the role of striatal D3R in focal dystonias. Development of a more selective D3R radioligand will be valuable for such studies.41

Our voxelwise whole brain exploratory analysis was consistent with VOI analysis and did not reveal any statistically significant differences in striatal BPND between the dystonics and healthy controls. We did not find any significant differences in cortical BPND either.

Numerous studies report age dependent reduction of dopamine receptors in humans and other mammals. Autopsy studies investigating the density of striatal D1-like receptors using [3H]SCH 23390 autoradiography showed marked decrease in the first decade of life but no significant reductions beyond age of 40.42 Two PET studies using [11C]SCH23390 demonstrated significant correlations between striatal binding and age in people ranging from either 6 to 93 years old (R2=0.39, p<0.001)43 or from 22–74 years old (R2=0.77, p<0.001).44 However such correlations were either not significant or substantially weaker at the age ranges corresponding to the more limited range of our participants. Our study has 90% power to detect a significant correlation between age and D1-like receptor density with R2=0.4 and p=0.05. The most likely reason that we did not detect a significant correlation with age may be the lack of a true correlation in this age range as would be anticipated from the previously reported post-mortem study noted above.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ms. Stacy Pratt for recruitment of subjects, healthy volunteers and our patients with focal dystonia who participated in this study. We also thank the Washington University Cyclotron Production Facility for preparation of the radiopharmaceutical used in these investigations, and are grateful to the NIMH Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program for the gift of desmethyl NNC 112.

Funding sources: This study was supported by NIH (K23NS069746, UL1 TR000448, NS41509, NS057105, NS075321); the Murphy Fund; American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) Center for Advanced PD Research at Washington University; Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function; and Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure/Conflict of interest: Authors have nothing to disclose

Author roles:

Morvarid Karimi: Conception, organization, execution of the research project, data analysis and writing of the first draft.

Stephen Moerlein: Execution of the research project, review and critique of the manuscript.

Tom Videen: Data analysis and review and critique of the manuscript.

Yi Su: Data analysis and review and critique of the manuscript

Hubert Flores: Data analysis and review and critique of the manuscript.

Joel Perlmutter: Conception of the research project, data analysis and review and critique of the manuscript.

Full financial disclosures of all authors for the past year:

| Stock Ownership in medically-related fields N/A |

Intellectual Property Rights N/A |

| Consultancies N/A |

Expert Testimony N/A |

| Advisory Boards N/A |

Employment Washington University in St. Louis |

| Partnerships N/A |

Contracts N/A |

| Honoraria N/A |

Royalties N/A |

| Grants K23NS069746 | Other N/A |

| Stock Ownership in medically-related fields N/A |

Intellectual Property Rights N/A |

| Consultancies N/A |

Expert Testimony N/A |

| Advisory Boards N/A |

Employment Washington University in St. Louis |

| Partnerships N/A |

Contracts N/A |

| Honoraria N/A |

Royalties N/A |

| Grants NIH | Other N/A |

| Stock Ownership in medically-related fields N/A |

Intellectual Property Rights N/A |

| Consultancies N/A |

Expert Testimony N/A |

| Advisory Boards N/A |

Employment retired/consultant for Washington University |

| Partnerships N/A |

Contracts N/A |

| Honoraria N/A |

Royalties N/A |

| Grants N/A | Other N/A |

| Stock Ownership in medically-related fields N/A |

Intellectual Property Rights N/A |

| Consultancies N/A |

Expert Testimony N/A |

| Advisory Boards N/A |

Employment Washington University in St. Louis |

| Partnerships N/A |

Contracts N/A |

| Honoraria N/A |

Royalties N/A |

| Grants NIH | Other N/A |

| Stock Ownership in medically-related fields N/A |

Intellectual Property Rights N/A |

| Consultancies N/A |

Expert Testimony N/A |

| Advisory Boards N/A |

Employment: Washington University in St. Louis |

| Partnerships N/A |

Contracts N/A |

| Honoraria N/A |

Royalties N/A |

| Grants 2R01NS05871404A1 5R01NS07552703 5R01NS07532102 5R01NS07532103 5R01NS04150911 |

Other N/A |

| Stock Ownership in medically-related fields N/A |

Intellectual Property Rights N/A |

| Consultancies N/A |

Expert Testimony N/A |

| Advisory Boards APDA (SAB); DMRF (MSAC) |

Employment: employer: Washington University in St. Louis |

| Partnerships N/A |

Contracts N/A |

| Honoraria U Rochester; Long Island jewish Medical Center; American Academy of Neurology; Society of Nucelar Medicine; Weill Conrell Medical College; U Saskatoon; U Maryland; U Louisville; Providence General Hospital; Med College of South Carolina; Emory University: Toronto Western University; Bachmann-Strauss Foundation; St. Lukes Hospital in St. Louis; Alberta Innovates; Penn State University; Movement Disorders Society |

Royalties N/A |

| Grants: NIH; Michael J Fox Foundation: APDA; Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA; Barnes jewish Hospital Foundation; McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function; CHDI; Express Scripts; Dystonia medical Research Foundation | Other N/A |

Reference List

- 1.Albanese A, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord. 2013;28:863–873. doi: 10.1002/mds.25475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wooten GF, Trugman JM. The dopamine motor system. Mov. Disord. 1989;4:S38–S47. doi: 10.1002/mds.870040506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider SA, Bhatia KP, Hardy J. Complicated recessive dystonia parkinsonism syndromes. Mov Disord. 2009;24:490–499. doi: 10.1002/mds.22314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poewe WH, Lees AJ, Stern GM. Dystonia in Parkinson's disease: clinical and pharmacological features. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:73–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nygaard TG. Dopa-responsive dystonia. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1995;8:310–313. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199508000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brancati F, et al. Role of the dopamine D5 receptor (DRD5) as a susceptibility gene for cervical dystonia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2003;74:665–666. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balcioglu A, et al. Dopamine release is impaired in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Yokoi F, Parsons DS, Standaert DG, Li Y. Alteration of striatal dopaminergic neurotransmission in a mouse model of DYT11 myoclonus-dystonia. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e33669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asanuma K, et al. Decreased striatal D2 receptor binding in non-manifesting carriers of the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Neurology. 2005;64:347–349. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149764.34953.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perlmutter JS, et al. Decreased [18F]spiperone binding in putamen in idiopathic focal dystonia. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:843–850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00843.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sciamanna G, et al. Impaired striatal D2 receptor function leads to enhanced GABA transmission in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2009;34:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karimi M, et al. Decreased Striatal Dopamine Receptor Binding in Primary Focal Dystonia: A D2 or D3 Defect? Mov. Disord. 2011;26:100–106. doi: 10.1002/mds.23401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun J, Xu J, Cairns NJ, Perlmutter JS, Mach RH. Dopamine D1, D2, D3 receptors, vesicular monoamine transporter type-2 (VMAT2) and dopamine transporter (DAT) densities in aged human brain. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e49483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinne JO, Hublin C, Nagren K, Helenius H, Partinen M. Unchanged striatal dopamine transporter availability in narcolepsy: a PET study with [11C]-CFT. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2004;109:52–55. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eidelberg D, et al. The metabolic topography of idiopathic torsion dystonia. Brain. 1995;118:1473–1484. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.6.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertram KL, Williams DR. Diagnosis of dystonic syndromes--a new eight-question approach. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012;8:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halldin C, et al. Carbon-11-NNC 112: a radioligand for PET examination of striatal and neocortical D1-dopamine receptors. J. Nucl. Med. 1998;39:2061–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mugler JP, III, Brookeman JR. Three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo imaging (3D MP RAGE) Magn. Reson. Med. 1990;14:68–78. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910150117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deichmann R, Good CD, Josephs O, Ashburner J, Turner R. Optimization of 3-D MP-RAGE sequences for structural brain imaging. Neuroimage. 2000;12:112–127. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziota JC. Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1992;16:620–633. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods RP, Mazziotta JC, Cherry SR. MRI-PET registration with automated algorithm. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1993;14:536–546. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giovacchini G, et al. Brain incorporation of 11C-arachidonic acid, blood volume, and blood flow in healthy aging: a study with partial-volume correction. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:1471–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller-Gartner HW, et al. Measurement of radiotracer concentration in brain gray matter using positron emission tomography: MRI-based correction for partial volume effects. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:571–583. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan J. Graphical analysis of PET data applied to reversible and irreversible tracers. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2000;27:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichise M, et al. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1096–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenstein SA, et al. Characterization of extrastriatal D2 in vivo specific binding of [18F](N-methyl) benperidol using PET. Synapse. 2012;66:770–780. doi: 10.1002/syn.21566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andersen PH, et al. NNC-112, NNC-687 and NNC-756, new selective and highly potent dopamine D1 receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;219:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90578-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou YH, Karlsson P, Halldin C, Olsson H, Farde L. A PET study of D(1)-like dopamine receptor ligand binding during altered endogenous dopamine levels in the primate brain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:220–227. doi: 10.1007/s002130051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson DA, Sejnowski TJ, Poizner H. Convergent evidence for abnormal striatal synaptic plasticity in dystonia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;37:558–573. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grundmann K, et al. Overexpression of human wildtype torsinA and human DeltaGAG torsinA in a transgenic mouse model causes phenotypic abnormalities. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;27:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sciamanna G, et al. Cholinergic dysregulation produced by selective inactivation of the dystonia-associated protein torsinA. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;47:416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dang MT, et al. An anticholinergic reverses motor control and corticostriatal LTD deficits in Dyt1 DeltaGAG knock-in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2012;226:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albin RL, et al. Diminished striatal [123I]iodobenzovesamicol binding in idiopathic cervical dystonia. Ann. Neurol. 2003;53:528–532. doi: 10.1002/ana.10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tu Z, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of in vitro bioactivity for vesicular acetylcholine transporter inhibitors containing two carbonyl groups. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:4422–4429. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zapata A, et al. Regulation of dopamine transporter function and cell surface expression by D3 dopamine receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:35842–35854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiorentini C, Busi C, Spano P, Missale C. Dimerization of dopamine D1 and D3 receptors in the regulation of striatal function. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010;10:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcellino D, et al. Identification of dopamine D1-D3 receptor heteromers. Indications for a role of synergistic D1-D3 receptor interactions in the striatum. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:26016–26025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710349200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhan L, et al. ALG-2 interacting protein AIP1: a novel link between D1 and D3 signalling. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;27:1626–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tziortzi AC, et al. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. Neuroimage. 2011;54:264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu J, et al. [(3)H]4-(dimethylamino)-N-(4-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl) butyl)benzamide: A selective radioligand for dopamine D(3) receptors. II. Quantitative analysis of dopamine D(3) and D(2) receptor density ratio in the caudate-putamen. Synapse. 2010;64:449–459. doi: 10.1002/syn.20748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cortes R, Gueye B, Pazos A, Probst A, Palacios JM. Dopamine receptors in human brain: autoradiographic distribution of D1 sites. Neuroscience. 1989;28:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rinne JO, Lonnberg P, Marjamaki P. Age-dependent decline in human brain dopamine D1 and D2 receptors. Brain Res. 1990;508:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, et al. Age-dependent decline of dopamine D1 receptors in human brain: a PET study. Synapse. 1998;30:56–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199809)30:1<56::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]