Abstract

This article focuses on design, training, and delivery of a culturally-tailored, multi-faceted intervention which used motivational interviewing (MI) and case management to reduce depression severity among African American survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV). We present the details of the intervention and discuss its implementation as a means of creating and providing culturally appropriate depression and violence services to African American women. We used a CBPR approach to develop and evaluate the multi-faceted intervention. As part of the evaluation, we collected process measures about the use of MI, assessed MI fidelity, and interviewed participants about their experiences with the program.

Introduction

A strong literature has documented the association between intimate partner violence (IPV) and depression (Anderson, Saunders, Yoshihama, Bybee, & Sullivan, 2012; Carbone-Lopez, Kruttschnitt, & Macmillan, 2006; Coker et al., 2002; Golding, 1999; Zlotnick, Johnson, & Kohn, 2006) including amongst African American women(Houry, Kaslow, & Thompson, 2005; Houry, Kemball, Rhodes, & Kaslow, 2006; McGuigan & Middlemiss, 2005). African Americans and IPV survivors share many common characteristics including lower acceptance of depression treatments and a great mistrust of the healthcare system (Cooper et al., 2003; Hamberger, Ambuel, Marbella, & Donze, 1998; McCauley, Yurk, Jenckes, & Ford, 1998; Nicolaidis, McFarland, Curry, & Gerrity, 2009). Both groups experience and attempt to resist unique forms of socio-economic marginalization such as sexism, racism, and classism.

Our academic-community partnership (the Interconnections Project) worked together for over five years, using a community based participatory research (CBPR) approach, to reduce depression care disparities among African-American and Latina IPV survivors. Together, we conducted a series of focus groups with African American(Nicolaidis et al., 2010), White(Nicolaidis et al., 2008), and Latina(Nicolaidis et al., 2011) depressed IPV survivors. Regardless of race or ethnicity, depressed IPV survivors shared the belief that their depression, physical health, and experiences of abuse are all extremely interconnected. African American women, however, voiced a particularly strong mistrust of healthcare, framing many of the problems as a lack of cultural understanding or outright discrimination(Nicolaidis et al., 2010). They stressed the importance of community-based, culturally specific services, and expressed great interest in programs that would increase their ability to take control of their depression and enable them to advocate for themselves within the health system.

Based on these findings, we collaboratively designed and implemented a culturally-tailored, multi-faceted intervention based on the Chronic Care Model(Wagner et al., 2001) to reduce depressive symptoms in African-American IPV survivors. A peer IPV Advocate served in the role of the health-system-based care manager, educating participants, using Motivational Interviewing (MI) to help women set and meet self-management goals, providing case management, and linking participants to the healthcare system.

This manuscript responds to a request that authors focus on the processes associated with MI interventions (Burke, Arkowitz, Dunn, 2002) so that we may better assess rigor and fidelity issues within the MI research community and to better support and understand this evidence based practice. Consequently, we discuss the details associated with our intervention (design, training, supervision, evaluation) and discuss our overall evaluation elsewhere (Nicolaidis et al., Under Review). In this article we discuss the intervention in depth including how we combined MI and case management, and the steps we took to support the training and practice of MI by a peer advocate. Our hope is that service providers and researchers interested in the use of MI with depression and IPV, as well as those interested in the applicability of MI within culturally specific services may learn from our challenges and successes.

MI to Address Depression

Motivational interviewing is an evidenced based practice defined as a collaborative, person-centered form of guiding to elicit and strengthen motivation for change (S. Rollnick, 2008). This humanistic and transpersonal approach to communication is designed to reduce discord and enhance client change talk. Applications of MI to social work have been discussed elsewhere (Forrester, McCambridge, Waissbein, Jones & Rollnick, 2007; Hohman, 2012; Wahab, 2005; Watson, 2011). Applications of MI to mental health treatment have begun to surface and have been widely tested and adapted a cross a range of behavioral arenas. Researchers and practitioners have made compelling cases for further exploration of MI’s application to depression treatment. Most recently, Grote, Swartz, Geibel, Zuckoff, Houck, & Frank (Grote et al., 2009) added an MI prelude session to interpersonal psychotherapy with depressed pregnant women with good overall results. Brody’s (Brody, 2012) case example of the successful use of MI with a depressed adolescent, argued that MI may be particularly useful for those who feel ambivalent about therapy and life choices. Arkowitz & Westra (Arkowitz & Westra, 2004) described the integration of MI into cognitive-behavioral therapy of depression and anxiety, while Simon, Ludman, Tutty, Operskalski, and Von Korff(Simon, Ludman, Tutty, Operskalski, & Von Korff, 2004) used structured MI exercises to enhance the engagement of primary care patients with depression via telephone cognitive-behavioral therapy.

MI to Address IPV

While less than a handful of studies have explored the use of MI with survivors of IPV, theoretical, anecdotal, and practice arguments have been made (Homan, Wahab, Slack, 2012; Wahab, 2006; Wahab & Motivational Interviewing and IPV Workgroup, 2010) been made that encourage practitioners and researchers to explore the value and usefulness of MI with survivors. Consistent with trauma informed work (Wahab & Motivational Interviewing and IPV Workgroup, 2010) MI focuses on strengths and self-efficacy, while emphasizing collaboration, empowerment, respect for choice, and understanding of the survivor’s perspective. When using MI with survivors of IPV, the focus of change needs to be on changes that survivors can control by themselves, including but not limited to behaviors associated with self-care, safety planning, health, social supports, addictions, and employment. By regarding individuals as experts on their own lives, MI supports practitioners to focus on building a sense of self-efficacy, sense of accomplishment and ability. The client centered nature of MI allows practitioners to meet survivors where they are, in their own process of change, this coupled with an evoking approach helps prevent the imposition of helper bias and control over survivors (Homan, Wahab, Slack, 2012).

Rasumussen, Hughes, & Murray (2012) conducted a pilot study of 20 women receiving services in a battered women’s shelter. Ten received services from shelter staff trained in MI, and ten received regular treatment services (without MI) from shelter staff. Findings suggest that women who received MI-enhanced services were significantly more ready to change a behavior than those who received regular treatment services.

Overview of the Interconnections project

The intervention discussed in this article took place within a community based participatory research (CBPR) project, the Interconnections Project, informed by Empowerment Theory and the Chronic Care Model. CBPR is defined as “a collaborative research approach that is designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organizations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process to improve health and wellbeing through taking action, including social change”(Viswanathan, 2012).

Our academic-community partnership was a collaboration between two universities and a community-based domestic violence agency which runs a drop-in center for African and African American women. Our research team included leaders from the African American community with collective experience as activists, performers, domestic violence advocates, and survivors, as well as academic researchers with collective expertise in health services, primary care, IPV, MI, and CBPR. Team members worked collaboratively with attention given to sharing power throughout all phases of the research process. The goal of the project was to develop and evaluate a culturally appropriate intervention for female African American survivors of IPV with major depression.

The intervention

Women who consented to participate in our study enrolled in a 6-month, multi-faceted intervention led by a peer IPV advocate. They met with the IPV advocate for individual MI counseling and/or case management services. Originally, (in Phase 1 of the project) women also had the option of attending 8 psycho-educational group sessions based on principles of cognitive behavioral therapy and led by the IPV advocate. However, due to low attendance to the sessions, we chose to eliminate the group element of the intervention and instead wove some of the cognitive behavioral and psycho-educational depression based content of the groups into the individual sessions. We referred to this portion of the intervention as Phase 2 and specifically merged some of the psycho-educational content from the groups into the individual sessions by engaging the Menu of Options tool for agenda setting detailed in Rosengren’s (2009) workbook. Women were invited to select one topic associated with depression and depression treatment to explore. See Figure 1. Topics for exploration included safety planning, spirituality, depression myths and truths, self care strategies, oppression awareness, fitness and health, alarming thoughts, and depression symptoms.

Figure 1.

Options tool.

Motivational interviewing

The MI portion of the intervention was designed to support the IPV advocate to create a non-judgmental, supportive environment for participants to move through various stages of change associated with depression, depression treatment, and IPV, as well as to guide them in exploring and ultimately strengthening their motivation for health-promoting change. Additional behavioral changes associated with topics including parenting, finances, education, employment, and self-care were also explored as the study participants ultimately chose what they wanted to focus on during the individual sessions.

Prior to working on this project, the peer advocate had no formal clinical or MI training. The peer IPV advocate received two initial introductory MI trainings specifically geared towards MI and IPV. The workshop occurred over a period of three days (two consecutive days with a third one-day follow up two weeks later) for a total of 18 hours. Unique issues and challenges associated with utilizing MI with IPV survivors and IPV advocates were addressed in the training and are discussed elsewhere (Homan, Wahab, Slack, 2012; Wahab, 2006; Wahab & Motivational Interviewing and IPV Workgroup, 2010). We chose to train a peer to become our MI professional because of the consistency with a CBPR approach to research valuing the wisdom, insight and talents of communities involved in research, as well as the CBPR focus on capacity building within communities. To support capacity building we invited domestic violence advocates from local agencies to participate in a three day MI (focused on IPV) training. Research also suggests the possibility of successfully training peer professionals in MI and Motivational Enhancement Therapies (MET)(Fromme & Corbin, 2004; Naar-King, Outlaw, Green-Jones, Wright, & Parsons, 2009; Tollison et al., 2008).

In addition to the introductory training, the IPV advocate received individual, in –person, ongoing, bi-monthly training and supervision for two years from the study co-investigator. Supervision sessions included a variety of activities including case debriefing and consultation, MI role and real plays, joint review of audio-taped MI sessions with study participants (discussed below), and joint use of the MITI 3.0(Moyers, 2012) fidelity tool while listening to study audio-taped sessions and training videos. The co-investigator providing this supervision also used MI with the advocate around behaviors she wished to change in her individual work with the study participants.

The co-investigator responsible for training the peer-advocate, has been an MI trainer since 2000 and is a member of the international network of MI trainers known as MINT. She is also a member of a special MI and IPV Workgroup associated with MINT, and teaches MI to undergraduate and graduate students in Schools of Social Work.

Case management

Case management services included providing information about depression, depression care, and IPV, as well as referrals to social services including but not limited to housing, welfare, child protection, mental health, childcare, education, employment, substance abuse, and faith-based services. Additional services included advocacy for and with study participants around legal, employment, housing, health, welfare, and domestic violence issues. It was not uncommon for the advocate to accompany women to their legal, healthcare, or welfare appointments. She also frequently accompanied women to court as a domestic violence advocate.

Evaluation

Women completed pre- and post-intervention surveys which included assessments of depression severity, attitudes about depression, self-management behaviors, healthcare utilization, self-efficacy, and self-esteem, as well as lifetime experiences of IPV. They also participated in an open-ended semi-structured exit interview focused on their perceptions of the interventions’ strengths and weaknesses. Details of the evaluation are discussed elsewhere (Nicolaidis et al., Under Review).

We recorded 10% of all MI intervention calls to assess MI fidelity. Recorded sessions were evaluated by the co-investigator using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale (MITI) 3.0(Moyers, 2012) assessment tool. The MITI codes both global counseling skills and the interventionist’s behavioral utterances. The MITI was selected for use over the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC)(Moyers, 2012) because it is shorter, requires less time, and is less complicated. The MITI utilizes 7-point Likert-type scales for 5 items (evocation, collaboration, autonomy/support, direction, and empathy), as well as simple tallies of interventionist behaviors, including giving information, MI adherent (asking permission, affirm, emphasize control, support), MI non-adherent (advise, confront, direct), questioning (open and closed), and reflecting (simple and complex). The MITI’s limitations are that it does not assess certain important components of MI, such as eliciting change talk, rolling with resistance, or exploring ambivalence(Madson & Campbell, 2006).

Results

A total of 59 women participated in the intervention (39 in Phase 1 and 20 in Phase 2). Participants engaged in 0–39 hours of individual MI counseling with a mean of 8 hours, in addition to 1–10 hours of case management with a mean of 2.1 hours.

While a general discussion of the overall study and findings is presented elsewhere (Nicolaidis et al., Under Review), it is relevant to mention here that we found significant improvements in depression severity from pre to post intervention outcome, with a reduction in PhQ-9 scores from 13.9 to 7.9, p <001. We also found improvements related to views about depression, depression self-efficacy, and depression self-management behaviors (p < .001 for all).

MI, depression and intimate partner violence

Topics they discussed

Topics women discussed tended to focus on depression (e.g, current symptoms of depression, depression self-care, anti-depressants, myths and facts about depression) and IPV (e.g., safety planning, experiences with recent violence, intimate partner relationships, effects of violence on children, IPV related legal issues, and parenting within violent relationships). Additional topics included issues related to health, employment, education, transportation, housing, and substance use. Consistent with some of the literature (Cooper et al., 2003; Wells et al., 2000). African American women in our study, including the IPV advocate, tended to avoid discussing (and accepting as an acceptable intervention) anti-depressant medications and mental health counseling.

Combining MI and case management

We chose to follow Robles, Reyes, Colon, Sahai, Marrero, Matos, Calderon, & Shephard’s (2004) approach to combining MI and case management on an as-needed basis once the MI work for that session was completed. If a need for resources, referrals or more direct advocacy surfaced during the MI portion of the session, the advocate asked permission to address the need(s) directly at the end of the session.

At first, the IPV advocate typically reserved case management for the end of the individual session. As the study developed and the advocate became more comfortable and proficient with MI, she became fluent in her abilities to move in and out of the two interventions without having to separate them so distinctly. Ultimately, she was able to provide case management within the spirit of MI by evoking ideas from participants rather than simply offering information and advice. Before providing information or advice, she elicited from study participants ideas they had about making designated changes. When appropriate she used the MI approach Elicit-Provide-Elicit (Rollnick, Mason & Butler, 1999). She would elicit permission to provide some information, resources, or referrals, then provide the content, then follow up by eliciting a response from the woman; for example, “what do you make of this?” or, “what are your thoughts about the suggestion I just shared with you?” As her MI proficiency skills increased, she was able to provide case management in a manner that honored study participants as experts in their own lives (even when it came to resources, supports, and needs), and engaged participants in a collaborative partnership. Through expressing empathy and being compassionate, she was able to provide case management in a way that facilitated study participants feeling heard, respected, and accepted (as noted below in our exit interview data).

Participants’ reflections on the intervention

Women who completed the study spoke in an overwhelmingly positive manner about their experiences with the intervention. Almost all (90%) of the women found the program to be very useful or useful, while 90% stated they would recommend the program to a friend. Women were particularly appreciative of having opportunities to talk individually with someone they could trust. Women overwhelmingly felt the IPV advocate was a safe and productive person to communicate with.

“I looked forward to our meetings. When we met I told her, I said, I couldn’t wait. If I had to cancel a meeting I didn’t like having to not be there. Because I just couldn’t wait to get into the meeting too because it was, a, um, a release for me. It was just a way for me to kinda talk and she always listened, and was there to help me through it.”

“The one-on-one was very useful because …it was things going on that I was depressed and sensitive about that I did not want it to lap over out into the community and then it would be back into the community and so I did one-on-one.”

They also expressed a recognition and appreciation for the spirit of MI as they commented on feeling understood, respected, accepted and listened to:

“She listened to my issues, and then…she provided positive feedback, um, how I could look at…the issues differently. What I could do if I wanted to change the issues. Um, how to make sure I’m in a safe environment.”

“What really helped was being able to bounce ideas off, you know. It’s different when you’re saying something and someone else is listening as opposed to just saying it out, you know, in the atmosphere. But having someone respond and that made it really helpful.”

“Being able to express anything I wanted to the way I wanted to. Not being feeling judged or feeling like OK I can’t say this because this person’s gonna, you know, feel this way.

Women also expressed feeling like they were in a partnership when working with the IPV advocate:

Or even if [the IPV advocate] had her opinion on something, she would say her thoughts, you know, and allow me to feel differently….she never forced her, her thoughts or her opinions on me. And always asked, um, if she could ask a question. Always asked. She always put me in, and one thing she always said was, ‘you always have a choice’, you know. So [she] made me feel comfortable.”

“And talk. You know. About it. Come up with solution together, you know. Letting someone know how you feel instead of havin’ penned up and you let it out in other areas.”

MI fidelity

As compared to recommended proficiency and competency thresholds (Moyers, 2012), the peer IPV advocate’s average threshold scores, over the course of the entire study period, demonstrated MI beginning proficiency in the following categories: global spirit, percent of complex reflections, and percent of open questions, as well as MI competency in the ratio of reflections to questions (see Table 1). MI adherence was rated as 83%, falling short of beginning proficiency when averaging scores over the course of the two years.

Table 1.

Summary MITI score thresholds

| Summary Score Thresholds | IPV Advocate |

|---|---|

| Global Spirit Rating | 3.6 |

| Global Direction | 3.1 |

| Global Empathy | 4.7 |

| Percent Complex Reflections | 45.3% |

| Percent Open Questions | 50.2% |

| Reflections-to-Questions | 3.3 |

| Percent MI-Adherent | 74% |

MITI scores coupled with supervision process notes demonstrate significant increases in MI proficiency over time with noticeable increases across all MITI categories. See Table 2 for MITI threshold scores comparing the first and last recorded intervention session. Perhaps of interest to the budding body of research associated with the “stages of learning MI”(Miller, 2000) is the increase in global direction over time.

Table 2.

Compared MITI score thresholds over time

| Summary Score Thresholds | IPV Advocate 1st recorded session |

IPV Advocate 2nd recorded session |

|---|---|---|

| Global Spirit Rating | 1.66 | 3.7 |

| Global Direction | 2 | 4 |

| Global Empathy | 3 | 5 |

| Percent Complex Reflections | 35% | 37% |

| Percent Open Questions | 25% | 60% |

| Reflections-to-Questions | 2.1 | 5.4 |

| Percent MI-Adherent | 100% | 100% |

Discussion

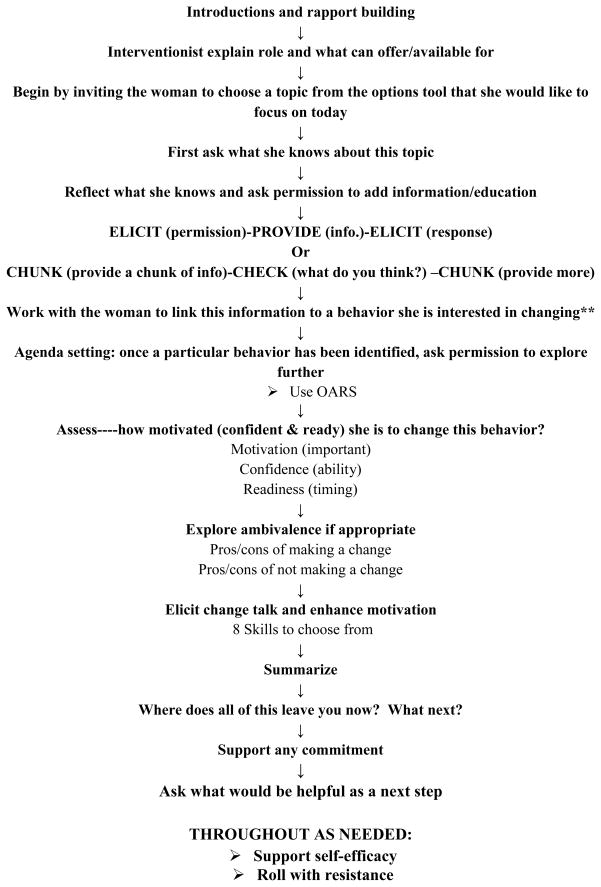

Given one of the researcher’s previous research experience using a road map (Wahab, Menon & Szalacha, 2008) we were ambivalent about creating one for this intervention. On one hand, we did not want to appear prescriptive about the MI interaction, particularly since the advocate was combining MI with case management and there was no telling if, when, and to what extent a woman would need one or the other in a given session. We wanted the advocate to feel like she could “dance” with the client, that is, meet her wherever she was without feeling the pressures of moving through a series of phases implied in a road map. On the other hand, we felt that having prompts or cues identifying MI strategies and skills to draw upon might be useful, particularly at the beginning of the project when the advocate was still becoming familiar with MI. Consequently, we settled on creating a suggested roadmap that the advocate could choose to use as she saw fit (Figure 2). In the end, the advocate found the road map useful in the beginning of the study and reported not needing or using the road map in the second year of the project as she felt comfortable and confident to draw on her previous experiences with the participants and her growing proficiency in MI.

Figure 2.

INTERCONNECTIONS SUGGESTED ROADMAP FOR MI INTERVENTION

The fact that the IPV advocate was a member of the community participating in the project, as well as a survivor of IPV and familiar with depression herself, facilitated certain strengths and challenges. As a member of the local African American community, rooted in its history, discourse, social and political issues, her insider status facilitated trust building with participants and meant she was aware of certain informal, kin, and religious based resources outside of those offered through the agency where she was based. However, the insider status occasionally complicated her relationships with study participants as she sometimes knew study participants and/or knew of the individuals who abused them. Consequently, navigating ethical issues around dual relationships and conflicts of interest were common and challenging topics engaged in supervision meetings.

The fact that the IPV advocate had personal and familial experiences with IPV and depression informed her learning and practice of MI. On one hand, her experiences with IPV and depression facilitated feelings of connection, empathy, and acceptance of survivors and their experiences. She expressed feeling a lot of tenderness, care, compassion, and hope for the study participants, while the study participants almost unanimously expressed (in the exit interviews) feeling like they could really talk with the advocate while not worrying about being judged or looked down upon. They felt understood by her and appreciated knowing that she had also shared similar experiences. On the other hand, the IPV advocated frequently struggled with counter transference issues exactly because she could relate to the study participants and was still in her own process of learning and healing. The counter transferences and intense identification (in particular) with some study participants facilitated feelings of judgment, impatience, sadness, and anger challenging her ability to practice within the MI spirit and leading her to be too directive and confrontive at times, taking on the “expert role.” Using MI in supervision with the advocate facilitated more of her own transformation and healing, and provided numerous opportunities to critically unpack and dissect the applicability and usefulness of MI.

Finally, as a peer to the women participating in the study the IPV advocate had her own doubts and beliefs about depression medication and mental health counseling. These doubts and beliefs made it difficult for her to raise and discuss the possibility of anti-depressants and counseling as an option with some participants, particularly the older participants. It was not infrequent for the IPV advocate to either stay away from these discussions all together or wait some time before raising these modalities as options. In the end, the IPV advocate’s practice with the study participants mirrored the broader social and cultural norms associated with these depression treatments.

There is no doubt that the ongoing MI training and supervision was crucial to enhancing the IPV advocate’s proficiency in MI beyond the initial introductory MI training sessions. As the IPV advocate became more comfortable and proficient in MI, her work with the study participants became more directive (as evidenced by the MITI scores) as she more frequently and effectively elicited and reflected change talk. (This data was recorded in the supervision process notes, as the MITI does not capture skills associated with eliciting change talk).

Conclusion

We believe that wisdom from within the African American community guided our project to create a useful and effective intervention using MI and case management to help reduce depression severity among African American IPV survivors. Interconnections Project team members were drawn to MI because of its spirit defined by collaboration, evocation, autonomy, and compassion. The spirit of MI that regards individuals as experts on their own lives, capable of making decisions for themselves, and valued as partners--even leaders--in their care resonated as empowering and consistent with what the African American women in our focus groups told us they wanted out of services focused on depression and IPV (Nicolaidis et al., 2010). Motivational interviewing presents an example of an evidenced based intervention that can be culturally tailored and responsive to community needs and knowledge while still being effective and rigorous. In our project, we were able to employ an evidence-based intervention to reduce depression severity among African American survivors of IPV and build community capacity for work in this area simultaneously.

Practice Implications

Future research and practice concerned with depression and IPV in the lives of African American women may consider MI as a possible intervention. Not only was MI used as an approach to provide culturally appropriate services, it was successful in helping to reduce depression severity among our small sample.

While our study suggests that training peer advocates in MI is possible, supports and resources particularly around training and supervision are considerable. That being said, there is no evidence (yet) that training peers and paraprofessionals in MI is any more resource intensive than training “professionals” in MI. As more research around what it takes to train people in MI to proficiency surfaces, we will be better able to make these comparisons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the former and current Bradley Angle House and Lifeworks NW employees who contributed to this project, as well as research assistants Janine Whitlock and Shalanda Carr. This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH073008 and 1R21MH082139; PI Nicolaidis) and the Kaiser Permanenete Community Fund- Northwest Health Foundation (grant #10571; PI Nicolaidis).

Contributor Information

Stéphanie Wahab, School of Social Work, Portland State University.

Jammie Trimble, Interconnections Community Partner at Large.

Angie Mejia, Department of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University.

S. Renee Mitchell, Interconnections Community Partner at Large.

Mary Jo Thomas, Multnomah County Department of Mental Health and Addictions.

Vanessa Timmons, Multnomah County Domestic Violence Office.

A. Star Waters, Interconnections Community Partner at Large.

Dora Raymaker, Department of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University.

Christina Nicolaidis, Departments of Medicine and Public Health & Preventive Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University.

References

- Anderson DK, Saunders DG, Yoshihama M, Bybee DI, Sullivan CM. Long-term Trends in Depression among Women Separated from Abusive Partners. Violence Against Women. 2012;9(7):807–838. [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H, Westra HA. Integrating Motivational Interviewing and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2004;18(4):337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Brody AE. Motivational interviewing with a depressed adolescent. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;65(11):1168–1179. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez K, Kruttschnitt C, Macmillan R. Patterns of intimate partner violence and their associations with physical health, psychological distress, and substance use. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):382–392. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester D, McCambridge J, Waissbein C, Emlyn Jones R, Rollnick S. Child risk and parental resistance: can motivational interviewing improve the practice of child and family social workers in working with parental alcohol misuse. [accessed 15 April 2007];British Journal of Social Work. 2007 [online advanced access]’, at http://www.oxfordjournals.org.

- Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate Partner Violence as a Risk Factor for Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14(2):99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, Zuckoff A, Houck PR, Frank E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(3):313–321. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiding as Practice: Motivational Interviewing and Trauma-Informed Work With Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence Motivational Interviewing and Intimate Partner Violence Workgroup. Partner Abuse. 2010;1(1):92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, Marbella A, Donze J. Physician interaction with battered women: the women’s perspective. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(6):575–582. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan M. Motivational interviewing in social work practice. New York: Guildford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hohman M, Wahab S, Slack K. Supporting self-efficacy or what if they think they can’t do it? In: Hohman M, editor. Motivational interviewing in social work practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Kaslow NJ, Thompson MP. Depressive symptoms in women experiencing intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(11):1467–1477. doi: 10.1177/0886260505278529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houry D, Kemball R, Rhodes KV, Kaslow NJ. Intimate partner violence and mental health symptoms in African American female ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(4):444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Yurk RA, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside “Pandora’s box”: abused women’s experiences with clinicians and health services. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan WM, Middlemiss W. Sexual abuse in childhood and interpersonal violence in adulthood: a cumulative impact on depressive symptoms in women. J Interpers Violence. 2005;20(10):1271–1287. doi: 10.1177/0886260505278107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. Motivational interviewing skills code (MISC): Coder’s manual. University of New Mexico; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR. Motivational Intervewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) code 3.0. 2012 from http://casaa.unm.edu/code/miti.html.

- Naar-King S, Outlaw A, Green-Jones M, Wright K, Parsons JT. Motivational interviewing by peer outreach workers: a pilot randomized clinical trial to retain adolescents and young adults in HIV care. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):868–873. doi: 10.1080/09540120802612824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Gregg J, Galian H, McFarland B, Curry M, Gerrity M. “You always end up feeling like you’re some hypochondriac”: intimate partner violence survivors’ experiences addressing depression and pain. Journal of general internal medicine. 2008;23(8):1157–1163. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, McFarland B, Curry M, Gerrity M. Differences in physical and mental health symptoms and mental health utilization associated with intimate-partner violence versus childhood abuse. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(4):340–346. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Perez M, Mejia A, Alvarado A, Celaya-Alston R, Galian H, et al. “Guardarse las cosas adentro” (keeping things inside): Latina violence survivors’ perceptions of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(10):1131–1137. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1747-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Timmons V, Thomas MJ, Waters AS, Wahab S, Mejia A, et al. “You don’t go tell White people nothing”: African American women’s perspectives on the influence of violence and race on depression and depression care. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(8):1470–1476. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Wahab S, Trimble J, Mejia A, Mitchell SR, Raymaker D, et al. The Interconnections Project: development and evaluation of a community-based depression program for African-American violence survivors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2270-7. (Under Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen LA. Applying Motivational Interviewing in a Domestic Violence Shelter: A Pilot Study Evaluating the Training of Shelter Staff - Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2012;17(3):296–317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926770802402980. 1080/10926770802402980. [Google Scholar]

- Robles RR, Reyes JC, Colon HM, Sahai H, Marrero CA, Matos TD, et al. Effects of combined counseling and case management to reduce HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic drug injectors in Puerto Rico: a randomized controlled study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S. Re: New working definition of motivational interviewing. 2008. IAMIT-L@LISTS.VCU.EDU. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Mason P, Butler C. Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. Edinburgh; New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren DB. Building motivational interviewing skills: A practitioner workbook. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, Operskalski B, Von Korff M. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(8):935–942. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollison SJ, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Neil TA, Olson ND, Larimer ME. Questions and reflections: the use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behav Ther. 2008;39(2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M. Community-based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evidence - NCBI Bookshelf. 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S. Motivational Interviewing and social work practice. Journal of Social Work. 2005;5(1):45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S. Motivational interviewing: A client centered and directive counseling style for work with victims of domestic violence. Arete. 2006;29(2):11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S Motivational Interviewing Intimate Partner Workgroup. Guiding as practice: Motivational interviewing and trauma informed-work with survivors of intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2010;1(1):92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S. Motivational Interviewing and Social Work Practice. Journal of Social Work. 2012;5(1):45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab S, Menon U, Szalacha L. Motivational interviewing and colorectal cancer screening: a peek from the inside out. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(2):210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Resistance is futile? Exploring the potential of motivational interviewing. Journal of Social Work Practice. 2011;25(4):465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unutzer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Kohn R. Intimate partner violence and long-term psychosocial functioning in a national sample of American women. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21(2):262–275. doi: 10.1177/0886260505282564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]