Abstract

A contextual model of self-protection is proposed to explain when adhering to cautious “if-then” rules in daily interaction erodes marital satisfaction. People can self-protect against partner non-responsiveness by distancing when a partner seems rejecting, promoting a partner’s dependence when feeling unworthy, or by devaluing a partner in the face of costs. The model implies that being less trusting elicits self-protection, and that mismatches between self-protective practices and encountered risk accelerate declines in satisfaction. A longitudinal study of newlyweds revealed that the fit between self-protection practices and risk predicted declines in satisfaction over three years. When people self-protected more initially, satisfaction declined more in low-risk (i.e., low conflict, resilient partner) than high-risk relationships (i.e., high conflict, vulnerable partner). However, when people self-protected less initially, satisfaction declined more in high-risk than low-risk relationships. Process evidence was consistent with moderated mediation: In low-risk relationships only, being less trusting predicted higher levels of self-protective caution that forecast later declines in satisfaction.

Keywords: self-protection, risk, longitudinal, newlyweds, procedural rules

Of all the forms of caution, caution in love is perhaps the most fatal to true happiness.

Bertrand Russell, The Conquest of Happiness

Is caution in love truly fatal to happiness? Some degree of self-protective caution does seem prudent. Because partners are interdependent in multiple ways, they cannot help but hurt and disappoint one another (Murray & Holmes, 2009). Given such rejection risks, partners might be wise to hesitate to depend on one another at certain times (Murray, Holmes & Collins, 2006; Wieselquist, Rusbult, Foster & Agnew, 1999). Nonetheless, being unduly cautious could easily prove fatal to happiness. Indeed, growing evidence suggests that sustained relationship satisfaction involves risking connection and making a leap of faith (see Gagne & Lydon, 2004; Fletcher & Kerr, 2010 for reviews). For instance, people who believe that their presumably imperfect partner mirrors their ideals experience no decline in satisfaction over the newlywed years (Murray, Griffin, Derrick, Harris, Aloni & Leder, 2011).

Because caution could help or hinder relationships, this paper advances a contextual model of self-protection and its effects on new marriages. Building on a new theory of interdependence (Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011), we conceptualize self-protection in terms of the “if-then” rules that govern thought and behavior. Our model assumes that Gayle can protect against rejection through her tendency to push Ron away when she fears rejection, to make efforts to increase his commitment to her when she feels unworthy of him, or to value him less when he interferes with her personal goals. Our model further assumes that the amount of self-protective caution Gayle exercises should depend on both her trust in Ron and the risks of rejection and non-responsiveness she actually encounters in her relationship. Consequently, being less trusting should only inspire self-protective caution that is fatal to satisfaction when such caution is not warranted by the severity of the encountered risks (Murray & Holmes, 2011).

The “If-Then” Rules for Motivating Responsiveness

Relationship satisfaction and stability depend on partners being mutually responsive to one another’s needs (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Reis, Clark & Holmes, 2004). However, behaving responsively is not always an easy task. Consider the typical experiences of newlyweds. Once married, partners shift their joint pursuits from leisure activities both partners desire to household drudgery neither partner enjoys (Huston, McHale & Crouter, 1986). Conflicts also increase as partners discover ways in which their personalities and relationship goals are incompatible (Huston et al., 1986; Huston, Caughlin, Houts, Smith, & George, 2001). For interactions to be rewarding in the face of emerging conflicts of interest, each partner must learn to accommodate his or her own interests and goals to meet the other partner’s interests and goals.

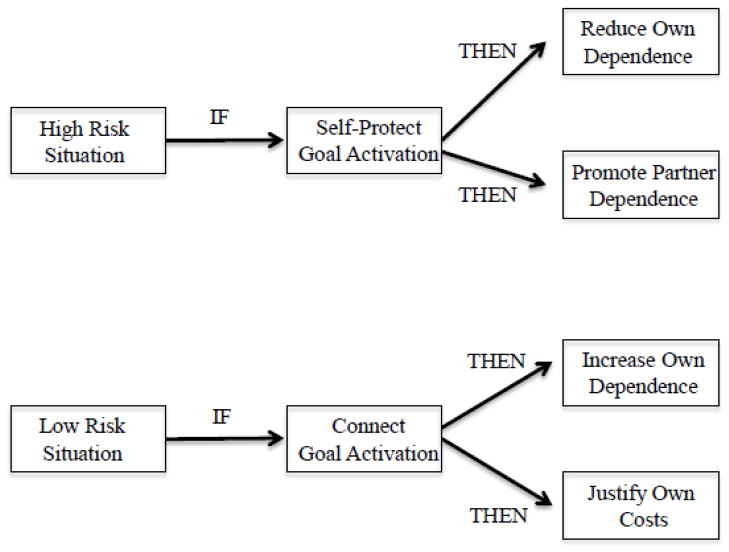

The motivation-management model of interdependence asserts that people’s general working models of relationships contain the “know-how” to coordinate mutually responsive behavior (Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011). This know-how corresponds to “if-then” rules that match Gayle’s willingness to depend on Ron to his perceived willingness to be responsive to her needs. Our research has demonstrated that these rules coordinate partners’ motivations by linking the level of risk in a given situation to correspondent interpersonal goals and behavioral strategies for goal pursuit (Murray, Aloni, Holmes, Stinson, Derrick & Leder, 2009; Murray, Derrick, Leder & Holmes, 2008; Murray & Holmes, 2011; Murray, Holmes, Aloni, Pinkus, Derrick & Leder, 2009). Figure 1 illustrates how these “if-then” rules govern partner interaction in situations that involve more or less apparent risk of a partner being non-responsive.

Figure 1.

The “If-then” Rules for Motivating Mutual Responsiveness

Imagine a conflict in which Gayle, a sports enthusiast who barely tolerates her in-laws, plans to golf the same weekend Ron wants her to attend his family reunion. Ron’s perception of such preferences makes the situation high in the risk of her non-responsiveness. Expecting Gayle’s rejection in such a situation (i.e., “if”) activates Ron’s state goal to self-protect against the possibility of her rejection and non-responsiveness. The activation of this goal then activates two complementary strategies (i.e., “then”) for meeting this goal (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2008). Namely, it activates the inclination to distance himself from Gayle until he has taken concrete steps to ensure that she depends on him in important ways, thereby ensuring her motivation to be responsive to him. For instance, he might not ask her to attend (i.e., reduce-own-dependence) until he fixes a computer problem for her (i.e., promote-partner-dependence).

Now imagine that Gayle only goes on golf weekends to make business connections and she enjoys her in-laws’ company. Ron’s perception of such preferences makes this situation low in the risk of her non-responsiveness. In such a situation, expecting Gayle’s responsiveness activates his state goal to connect to her. The activation of this goal (i.e., “if”) elicits two complementary strategies (i.e., “then”) for meeting this interpersonal goal. Namely, it activates the inclination to draw closer to Gayle and justify any costs he incurs as a result of his stronger connection (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). For instance, he might ask her to skip golfing to attend the reunion (i.e., increase-own-dependence). On her acceptance of his request, he then might see her athleticism more positively when she wakes him to go running on the morning of the reunion rather than letting him sleep as he wished (i.e., justify-own-costs).

Experimental and daily diary research supports the existence and function of each of these “if-then” rules. In formal terms, the “promote-partner-dependence” rule links acute feelings of inferiority to the partner (i.e., “if”) to the tendency to put the partner in one’s debt (i.e., “then”). For instance, subliminally priming the exchange script, and thereby activating acute feelings of inferiority, elicits the desire to do instrumental favors for one’s partner (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009). In daily interaction, newlyweds react to acute feelings of inferiority to their partner by providing more instrumental favors for their partner on subsequent days (e.g., doing their partner’s chores, running their errands). The “reduce-own-dependence” rule links acute concerns about the partner’s rejection (i.e., “if”) to the tendency to distance oneself from the partner (i.e., “then”). For example, priming a partner’s past transgression automatically elicits hostility-related thoughts (Murray, Derrick et al., 2008). People who are likely to act on the “if-then” rules because their executive resources are taxed also respond to a dating partner’s imagined transgressions with hostility (Finkel & Campbell, 2001). The “justify-own-costs” rule links acute awareness of the costs a partner imposes (i.e., “if”) to the compensatory tendency to value the partner more (i.e., “then”). In daily interaction, putting the “justify-own-costs” rule into practice fosters a stronger sense of connection to the partner. For example, newlyweds behave more responsively toward their partner on the days after they compensated for the costs their partner imposed on their personal goals. Newlyweds who respond to their partner’s daily obstruction of their personal goals by valuing their partner on subsequent days also report more stable satisfaction over the first year of marriage (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009).

The motivation-management model further assumes that practicing self-protection can simultaneously protect and strengthen relationships because some of the situations partners encounter truly merit caution. The risk of non-responsiveness varies across situations within a given relationship and across relationships because partners are interdependent in life tasks, personality, and relationship goals (Kelley, 1979; Murray & Holmes, 2009; Overall & Sibley, 2008). In fact, partners do not selectively assort on basic dimensions of personality, ensuring that some incompatibility is the rule for all but the fortunate few (Lykken & Tellegen, 1993). Because incompatible preferences increase the risk of non-responsiveness (Kelley, 1979), partners with less objectively compatible preferences are likely to face more high-risk situations – making applying self-protective “if-then” rules a better bet for soliciting partner responsiveness and fostering fluid interaction patterns (Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011).

For instance, if Gayle really is likely to be non-responsive, Ron taking a necessary self-protective step to make her need him increases his chance of avoiding rejection (relative to simply approaching Gayle). However, if Ron has misjudged Gayle’s responsiveness, his taking the unnecessary step of making her owe him before he solicits a sacrifice leaves him uncertain whether he should attribute her responsiveness to her caring or her debt to him (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009). In the former case, Ron turned a potentially bad situation into a relatively good one. In the latter case, he turned a potentially good situation into a relatively bad one. Applied across interactions, this logic implies that the “if-then” rules people practice can change the nature of the risks and rewards inherent in the situations they encounter to either good or bad effect.

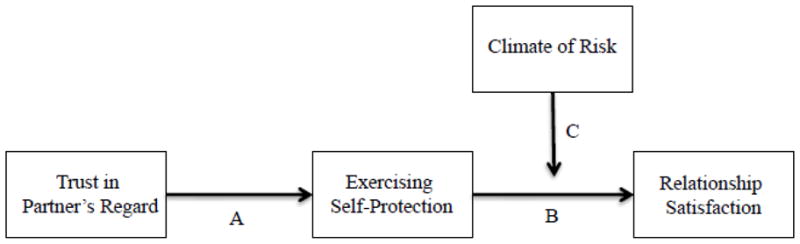

A Contextual Model of Self-Protection

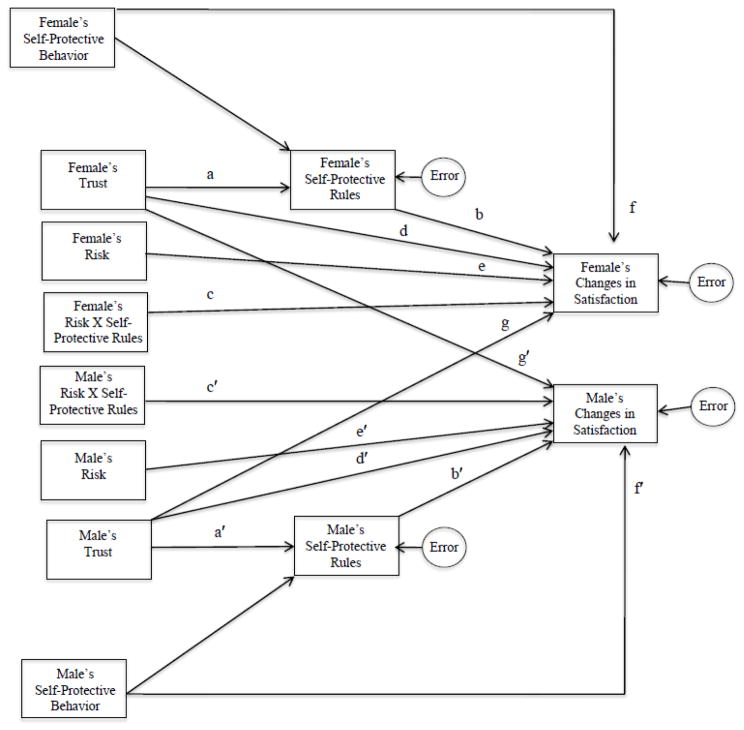

Figure 2 presents the contextual model of self-protection that results from the assumption that people can misperceive risk and self-protect (or fail to self-protect) when it is not in the relationship’s long-term interest. This contextual model hypothesizes that being less trusting only inspires self-protective caution that undermines satisfaction when caution is not warranted by the encountered risks. In technical terms, it specifies a pattern of moderated mediation (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007). Namely, a mediator (i.e., exercising self-protection) explains the association between a hypothesized cause (i.e., being less trusting) and effect (i.e., declines in satisfaction) under specific conditions (i.e., low risk of non-responsiveness).

Figure 2.

A Contextual Model of Self-Protection in Relationships

Path A captures the hypothesis that chronic trust in the partner’s responsiveness regulates self-protective caution. Trust captures the expectation that one’s partner is likely to be responsive to one’s needs, both now and in the future (Holmes & Cameron, 2005; Holmes & Rempel, 1989; Rempel, Holmes & Zanna, 1985; Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011). We expect people who are less trusting to exercise greater self-protective caution because being less trusting sensitizes them to the potential for rejection in ambiguous situations (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry, & Kashy, 2005; Collins & Feeney, 2004; Murray, Bellavia, Rose & Griffin, 2003). For instance, people who generally feel less valued by their spouse are more likely to practice the “reduce-own-dependence” rule; they react to feeling acutely rejected by their partner by engaging in more rejecting and hostile behaviors on subsequent days (Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003). Less trusting people also overreact to daily conflicts, treating them as an excuse to withdraw from the relationship (Campbell, Simpson, Boldry & Rubin, 2010).

We also expect people who are less trusting to exercise greater self-protective caution because being less trusting supplies the motivation to correct “if-then” inclinations to connect to the partner (Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011). For people who are less trusting, the state goal to connect to the partner contradicts a chronic goal to protect against the chance of being hurt by the partner (Murray & Holmes, 2009). As a result, a less trusting Ron might ultimately conclude that Gayle is selfish for waking him because cynicism better serves his chronic goal to self-protect and keep himself from feeling too attached to Gayle. Consistent with this logic, low self-esteem people primed with the ways in which their partner thwarts their personal goals are faster to associate their partner with positive traits, automatically justifying such costs. However, low self-esteem people override such automatic inclinations and value their partner less on explicit measures that afford the overt behavioral opportunity to correct (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). In contrast, high self-esteem newlyweds act on the automatic inclination to justify their costs in daily interactions; on days after their partner interfered with more of their goals, high self-esteem people report loving and valuing their partner all the more (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009).

Paths B by C capture the assumption that self-protection is more likely to precipitate declines in satisfaction (Path B) when it is out of touch with likely risks (moderating Path C). In other words, continuing satisfaction depends on the match between the “if-then” rules people practice and the relationship risks they encounter (for similar contextual arguments see McNulty & Karney, 2004; McNulty, O’Mara & Karney, 2008; McNulty & Russell, 2010).

Practicing more self-protective “if-then” rules prioritizes avoiding the possibility of a partner’s rejection and non-responsiveness over the possibility of soliciting the partner’s acceptance and responsiveness. Such practices are a good fit to high-risk relationships. The situations comprising high-risk relationships typically make it difficult for a partner to behave responsively; thus, taking steps to ward off a high likelihood of partner non-responsiveness is judicious. Indeed, practicing self-protection can avert negative outcomes. For instance, when people respond to feeling inferior by increasing their partner’s debt to them (e.g., running his/her errands), it actually increases their partner’s daily commitment (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009). Through such reparative processes, practicing greater caution might make high-risk situations less costly by motivating partners to behave more responsively.

However, self-protective practices are a poor fit to low-risk relationships. The situations comprising low-risk relationships typically make it easy for a partner to behave responsively; thus, taking cautious steps to ward off a low likelihood of partner non-responsiveness is unwise. For instance, practicing self-protection could forego some of the positive experiences that seeking connection to the partner could realistically offer. If Ron risks dependence on Gayle by seeking help and support, the occasion offers the opportunity to realize the benefits of being with a responsive partner. However, he would miss such available opportunities if he routinely took the step of pushing her away from him whenever he felt insecure. Further, when Ron reacts to the daily costs Gayle imposes on his personal goal pursuits by valuing her more, Gayle perceives him as behaving more responsively (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). Consequently, too-often correcting the inclination to justify costs could create missed opportunities to be responsive (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). Being unduly cautious could also trigger self-fulfilling prophecies in which Gayle’s hesitations around Ron elicit his rejecting behavior toward her (Downey, Freitas, Michaelis, & Khouri, 1998; Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003). Through such degenerative processes, practicing greater self-protective caution might make low-risk situations more costly by giving partners greater reason not to be responsive.

The moderated mediation hypothesis that integrates paths A through C posits that being less trusting disposes people to self-protect in situations where they should instead connect. This misapplication logic presupposes a disassociation between trust and risk. Though based in a kernel of truth (Wieselquist et al., 1999; Simpson, 2007), trust is essentially an expression of faith (Holmes & Rempel, 1989). In fact, being highly trusting requires going beyond behavioral evidence to conclude that one’s partner will always want to take care of one’s needs. Making such a leap of faith requires confidence in one’s own worthiness of love (see Murray & Holmes, 2011 for a review). Because trust in one partner’s caring and commitment has such a large projective component, it can misdiagnose the actual risk of a partner behaving non-responsively (e.g., Murray et al., 2000). In particular, in low risk relationships, being less trusting is likely to overestimate risk. Therefore, in low-risk relationships, being less trusting could elicit poor-fitting rule habits that compromise opportunities for happiness. However, in high-risk relationships, being less trusting is more likely to elicit better-fitting, more functional, rule habits that have more positive than negative effects. Accordingly, in low risk settings, it is being cautious to a fault that should prove fatal to true happiness.

Research Strategy and Hypotheses

Because marital instability puts physical and psychological health at risk, identifying factors that predict declines in marital satisfaction is of great practical importance (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). The current paper utilizes an existing sample of newlyweds to test a new set of longitudinal hypotheses. In so doing, it provides the first test of a new perspective on interdependence that attributes power to make or break relationship bonds to the “if-then” rules partners practice (Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011). Within six months of marriage, both members of newlywed couples completed interaction diaries every day for two weeks. These diaries allowed us to index the strength of the “reduce-own-dependence”, “promote-partner-dependence”, and “justify-own-costs” rules each partner exercised early in marriage. We then obtained measures of satisfaction every six months over the next three years.i, ii

When Reality Bites

Our contextual model posits that the fit between self-protection practices and the relationship’s risk climate determines satisfaction trajectories. But how might we best index risk? Ron’s commitment or level of positive regard for Gayle might seem to be the most obvious indicator of the risk of his non-responsiveness (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). However, the newly married typically express ebulliently positive sentiments toward one another (McNulty & Karney, 2004; Murray et al., 2011). Such sentiments typically mask underlying sources of difficulty in the relationship, making them a less than sensitive barometer of risk (Huston et al., 1986). We utilized two indicators of risk likely to be less contaminated by sentiment override at the point of marriage: (1) conflict frequency, and (2) the partner’s personal vulnerability.

We utilized conflict frequency as a barometer of risk because early conflicts are typically a sign that partners possess reasonably incompatible preferences (Kelley, 1979; Markman, 1979; 1981). We utilized the partner’s self-reported personal vulnerability as a further risk barometer because people who are low in self-esteem (Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes & Kusche, 2002), sensitive to rejection and loss (Downey & Feldman, 1996), anxious in attachment (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003), and high in neuroticism (Karney & Bradbury, 2007) are more likely to evidence the kinds of negative thoughts and behaviors that can compromise their capacity to be rewarding and responsive partners over the longer term (see Murray & Holmes, 2011 for a review).

We expected being less trusting to inspire self-protective caution that forecasted declines in satisfaction when caution was not warranted by the encountered risks. This prediction subsumes three hypotheses. First, when people practice more self-protective rules in daily life, satisfaction should decline more in low-risk relationships (where caution is a poor fit to the context) than high-risk relationships (where caution is a good fit to the context). In contrast, when people practice less self-protective “if-then” rules, satisfaction should decline more in high-risk relationships (where not being cautious is a poor fit to the context) than in low-risk relationships (where not being cautious is a good fit to the context). Second, people who are less trusting should practice more self-protective “if-then” rules. Third, practicing greater self-protection (i.e., the mediator) should explain the association between trust (i.e., the cause) and declines in satisfaction (i.e., the effect) in low-risk, but not high-risk, relationships.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and twenty-two childless couples in first marriages between two and six months in length participated in a 7-wave longitudinal study in upstate NY. Eleven couples separated or divorced during this time period. The final sample consisted of the 193 couples that completed 3 or more of the bi-annual assessments. The sample was predominantly White (89%). At Time 1, participants averaged 27.2 (SD = 4.0) years in age and the median family income ranged from $40,000-$70,000 per year. Participants received escalating payment for each wave.

Procedure

Couples who were applying for marriage licenses in City Clerk’s offices throughout the Buffalo area received flyers inviting them to participate in a longitudinal study of marriage. Interested participants (who met the eligibility criteria: first marriage, no children) completed the first assessment at least 2 but no more than 6 months after they married.

Prior to the lab session, each participant completed a measure tapping basic aspects of self-perception and personality (e.g., attachment, NEO-FFI) at home. On arriving at the lab session, each participant then completed further measures tapping self (e.g., self-esteem) and relationship perceptions (e.g., trust, satisfaction). The graduate assistant then introduced the procedures for completing the daily diary on a Dell Axim PDA.

The electronic diary program indexed the events and emotional experiences of the day. Using the PDA, participants indicated whether each of 91 events had occurred on a given day. General categories of events included interactions with the spouse, success or failure at work, and managing household/family responsibilities. Each event-item appeared (in random order) on the PDA screen and participants used a stylus to select yes or no. Participants also rated their feelings on 42 items each day. Feeling categories included self-evaluations, perceptions of the partner’s regard, perceptions of the partner, and evaluations of the relationship. Each feeling-item (randomly ordered within categories) appeared on the screen and participants used the stylus to select a scale point indicating the strength of that feeling (on scales anchored 0 = not at all, 6 = especially). The graduate assistant instructed participants to begin the diaries the day after their lab appointment, to complete them as close to going to bed at night as possible, and to refrain from discussing their responses with one another. (The PDA was programmed such that participants were unable to complete the diary until the evening hours.) Each member of the couple left with a PDA (color-coded by gender) and a reminder sheet that summarized the procedures. They returned to the lab after 14 days to complete a questionnaire that assessed their experiences in completing the diaries. The graduate assistant described the broad purposes of the study and paid and thanked each couple.

Participants were re-contacted 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months after the initial assessment to complete a global measure of satisfaction (among other measures). Participants completed these questionnaires in the laboratory at the initial, 12, 24, and 36-months and by mail at 6, 18, and 30-months. We detail only those measures relevant to the current paper.

Self-Perceptions

Self-esteem

The 10-item (α= .88) Rosenberg (1965) scale tapped global feelings of self-worth (e.g., “I feel like a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others”). Participants responded on 7-point scales (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

Neuroticism

The 12-item subscale (α= .84) of the NEO-FFI (Macrae & Costra, 2004) indexed dispositional neuroticism (e.g., “I am not a worrier”, reversed; “I often feel tense and jittery). Participants responded on 5-point scales (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

BIS Sensitivity

The 7-item scale (α= .76) tapping Behavioral Inhibition Sensitivity (Carver & Weight, 1994) indexed dispositional concern about the possibility of experiencing bad outcomes (“If I think something bad is going to happen, I usually get pretty worked up”). Participants responded on 4-point scales (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree).

Attachment anxiety

Participants rated how well each of 4 attachment style prototypes (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) described their general orientation in relationships (1 = not at all like me; 7 = very much like me). We computed an index of attachment anxiety by subtracting summed responses to the secure and dismissing prototypes from summed responses to the preoccupied and fearful prototypes (Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994).

Relationship Perceptions

Trust

This 10-item measure (α= .85), developed from Rempel et al., (1985), tapped trust in the partner’s continuing motivation to be responsive to one’s needs (e.g., “Though times may change and the future is uncertain, I know my partner will always be ready and willing to offer me strength and support”; “When we are dealing with an issue that is important to me, I feel confident that my partner will put my feelings first”; “I feel that I can trust my partner completely”; “My partner is a thoroughly dependable person”; “My partner sometimes fails to take my needs into account when he/she makes decisions affecting us both”, reversed). Participants responded on 9-point scales (0 = not at all; 8 = completely true).

Satisfaction

This 4-item measure (α= .84), developed by Murray, Holmes and Griffin (1996; 2000), tapped global feelings of satisfaction in the marriage (e.g., “I am extremely satisfied with my relationship”; “My relationship with my partner is very rewarding”). Participants responded on 9-point scales (0 = not at all; 8 = completely true).

Conflict-frequency

This 5-item measure (α= .89) tapped the severity and frequency of conflict (e.g., “How often do you and your partner have arguments or disagreements”, 1 = almost never; 7 = every day; “In general, how serious are your arguments and disagreements”; 1 = not at all serious, 7 = extremely serious).

The If-Then Rule Indices

Reduce-own-dependence rule

This rule, derived from two daily diary measures, links perceptions of the partner’s rejection (IF) to the tendency to push the partner away (THEN), thereby distancing oneself from the partner. To index this rule, we utilized daily responses to 12 feelings-items (α= .94) tapping perceptions of the partner’s rejection (e.g., “I feel rejected or hurt by my partner”; “My partner doesn’t care what I think”; “I can’t count on my partner”; “My partner doesn’t listen to me”) and responses to 8 event-items tapping cold, distant behavior (e.g., “I snapped or yelled at my partner”; “I ignored or didn’t pay attention to my partner”; “I criticized or insulted my partner”; “I pushed or hit my partner”). As in prior research on this rule using this sample (Murray, Holmes & Pinkus, 2010), we estimated a multilevel model predicting today’s cold, distant behavior from the intercept, the fixed effect of yesterday’s behavior, and the random effect of yesterday’s perceptions of the partner’s rejection, and error terms. In this model, the residual component of the intercept captures how often each person behaved in a cold, distant way across days. The residual component of the slope captures how much each person responds to feeling rejected by the partner by engaging in cold behavior that is likely to push the partner away. More positive slopes index greater self-protection (i.e., a stronger tendency to respond to feeling rejected by engaging in cold, distancing behavior the next day).iii, iv

Promote-partner-dependence rule

This rule, derived from two daily diary measures, links personal feelings of inferiority to the partner (IF) to the tendency to behave in ways that ensure that the partner relies on oneself (THEN). To index this rule, we utilized daily responses to 5 feelings-items (a = .79) tapping felt inferiority (e.g., “I’m not good enough for my partner”; “My partner is a better person than I am; My partner is more fun to be around than I am”) and 8 event-items tapping communal behavior (e.g., “I searched for something my partner had lost”; “I went out of my way to run an errand for my partner”; “I repaired something my partner had damaged or broken”; “I packed a snack/lunch for my partner to take to work or school”: Clark & Grote, 1998). As in prior research on this rule using this sample (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009), we estimated a multi-level model predicting today’s communal behavior from the intercept, the fixed effect of yesterday’s communal behavior, the random effect of felt inferiority, and error terms. In this model, the residual component of the intercept captures how often each person engaged in communal behavior across days. The residual component of the slope captures how much each person responds to feeling inferior by engaging in behaviors that could increase their partner’s dependence on them. More positive slopes index greater self-protection (i.e., a stronger tendency to respond to feeling inferior by working to ensure the partner’s dependence).

Justify-own-costs rule

This rule, derived from two further daily diary measures, links the perception that the partner has interfered with one’s personal goals (IF) to the tendency to value the partner more (THEN). To index this rule, we utilized daily responses to 5 event-items tapping the partner’s infringement on one’s personal goals (e.g., “My partner used the last of something I needed and did not replace it”; “My partner didn’t do something he/she said he/she would do”; “My partner did what he/she wanted to do instead of what I wanted him/her to do”) and responses to 3 feelings-items (a = .76) tapping valuing of the partner (e.g., “My partner is a great person”; “In love with my partner”). As in prior research on this rule using this sample (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009), we estimated a multi-level model predicting today’s valuing of the partner from the intercept, the fixed effect of yesterday’s valuing of the partner, the random effect of yesterday’s perceived goal-infringement, and the error terms (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). In this model, the residual component of the intercept captures how much each person valued the partner across days. The residual component of the slope captures how much each person responds to goal-infringement by valuing the partner more. More positive slopes index less self-protection (i.e., a stronger tendency to respond to having one’s goals thwarted by valuing the partner more the next day). Accordingly, we reverse-scored the slope (i.e., multiplied by minus 1), so that more positive justify-cost slopes capture greater self-protection.

Results

In proceeding, we first describe the logic and analyses underlying our indices of self-protective “if-then” rule habits and experienced risk. Next, we utilize a multilevel modeling approach to determine whether self-protective “if-then” rule habits and risk interact in predicting changes in satisfaction. When people initially practiced more self-protective “if-then” rules, we expected satisfaction to decline more in low-risk (i.e., low initial conflict, partner who is more personally resilient) than high-risk relationships (i.e., high initial conflict, partner who is more personally vulnerable). In contrast, when people initially practiced less self-protective “if-then” rules, we expected satisfaction to decline more in high-risk than low-risk relationships. Finally, we then utilize a structural equation model to test the moderated mediation hypothesis. We expected people who were less trusting to practice more self-protection. We also expected practicing self-protection to put less trusting people at risk for steeper declines in satisfaction when such caution was not appropriate to the encountered relationship risks (i.e., low initial conflict, partner who is more personally resilient).

Indexing Self-Protective Rule Habits

The motivation-management model assumes that self-protection is best indexed as the sum of its “if-then” parts. Qualitatively different (and empirically separable) situations activate each of the “if-then” rules (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009; Murray, Holmes et al., 2009; Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011). For instance, feeling hurt and rejected activates the tendency to distance and push one’s partner away, but not the tendency to do dependence promoting favors. Feeling inferior to one’s partner instead activates the tendency to do dependence-promoting favors.

In any given relationship, exposure to one type of situation need not predict exposure to the other types of situations. Different relationships also expose partners to different situations. Consequently, depending on the situations they encounter in their relationship, people can develop quite idiosyncratic signatures to the ways in which they do (or do not) practice self-protection. For instance, frequent experience of feeling rejected by Gayle might strengthen Ron’s habit to reduce his dependence without also strengthening his habit not to justify his costs. Consistent with this supposition, Table 1 reveals that the reduce-own-dependence, promote-partner-dependence, and justify-own-costs rules were only minimally inter-correlated.v

Table 1.

Time 1. Zero correlations among the “if-then” rules.

| Reduce-own-dependence rule | Promote-partner dependence rule | Justify-own-costs rule (RV) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce-own-dependence | 1.00 | .02 | .08 |

| Promote-partner-dependence | .14 | 1.00 | −.02 |

| Justify-own costs (RV) | .20 | .03 | 1.00 |

NB. The correlations for women are above the diagonal; the correlations for men are below the diagonal.

Because the constitution of self-protective habits is idiosyncratic, considering each “if-then” rule in isolation could miss what self-protection entails for a particular person. For instance, utilizing the “reduce-own-dependence” rule might aptly capture how Ron self-protects but might fail to capture how Gayle self-protects. Such divergence implies the logic of a formative rather than a reflective measurement model. In reflective measurement models, the underlying construct (e.g., self-esteem) causes the indicators (e.g., responses to self-esteem items), and consequently, the indicators should be strongly correlated (i.e., internal consistency). In formative measurement models, the indicators cause the construct, and consequently, strong correlations among the indicators are not expected. Socioeconomic status provides a good example of a formative index. Any combination of high income, prestigious job, or posh residence could increase SES, without all measures increasing simultaneously (Diamantopoulos, Riefler & Roth, 2008; Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001).

Self-protection functions similarly. Just as displays of wealth are idiosyncratic to the person, people can develop some “if-then” habits to self-protect and not others because of the specific situations they face. For this reason, we created a composite index of self-protective rule use. We summed the slope residuals (i.e., the residuals capturing each person’s tendency to respond to feeling rejected by engaging in more cold and distancing behavior, to respond to feeling inferior to the partner by promoting the partner’s dependence, and to respond to goal infringement by valuing the partner more, reversed). By utilizing the composite index, we allow Ron and Gayle to score similarly on self-protection (the underlying variable) even if they practice self-protection in different ways (the measured variables).

For control purposes, we also created a composite index of self-protective behavior by summing the intercept residuals (i.e., the indices capturing each person’s average level of distancing behavior, average level of dependence-promoting behavior, and average level of partner-valuing, reversed). Controlling for the average level of self-protective behavior in our analyses allows us to separate the effects of enacting self-protective rules (i.e., “if-then” contingencies in thoughts and behavior) from the effects of the constituent behaviors.

Indexing Encountered Risk

We indexed risk through people’s own reports of conflict and the partner’s self-reported personal vulnerability. To index the personal vulnerability of the partner, we averaged the partner’s z-score-transformed responses to the neuroticism, attachment-anxiety, BIS, and self-esteem (reverse-scored) scales (α= .79). We computed an overall index of the relationship’s risk climate for Ron by summing his perception of conflict (z-scored) and Gayle’s level of personal vulnerability. Similarly, we indexed the overall risk climate for Gayle by summing her perception of conflict (z-scored) and Ron’s level of personal vulnerability. Table 2 presents the inter-correlations among the predictor and criterion variables, separately for men and women.

Table 2.

Zero correlations among the primary variables at the initial assessment.

| Trust | Satisfaction | Conflict | Partner Vulnerability | Risk Composite | Self-Protective Rules | Self-Protective Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 1.00 | .71 | −.51 | −.11 | −.43 | −.17 | −.19 |

| Satisfaction | .76 | 1.00 | −.49 | −.12 | −.42 | −.21 | −.20 |

| Conflict | −.56 | −.53 | 1.00 | .17 | .83 | .16 | .25 |

| Partner Vulnerability | −.10 | −.19 | .23 | 1.00 | .71 | .06 | −.03 |

| Risk Composite | −.45 | −.49 | .84 | .73 | 1.00 | .13 | .17 |

| Self-Protective Rules | −.18 | −.21 | .25 | .17 | .24 | 1.00 | .24 |

| Self-Protective Behavior | −.23 | −.18 | .22 | .08 | .20 | .21 | 1.00 |

NB. The correlations for women are above the diagonal; the correlations for men are below the diagonal.

Fitting the Rules to Risk Climate: Predicting Satisfaction Trajectories

The interaction effect in Figure 2 (path B moderated by the level of C) stipulates that declines in satisfaction depend on the fit between the rules partners practice and the risk climate. To test this hypothesis, we used MLwiN (Goldstein et al., 1998) to model our data as a three-level nested structure with time at the lowest level, person at the second level, and gender within couple at the highest level. This approach is advantageous because it allows efficient tests of gender differences and pooling of coefficients in their absence.vi

We predicted satisfaction at each time point from: (1) an intercept term, (2) the linear effect of time, scored 0 to 6, a fixed effect that captures the average trajectory of change in satisfaction, (3) the centered main effect of actors’ self-protective rule use, a fixed effect that captures whether actors who exercise greater self-protection are less satisfied initially, (4) the centered main effect of actors’ initial level of risk, a fixed effect that captures whether actors exposed to greater risk are less satisfied initially, (5) the two-way interaction between time and actors’ self-protective rule use, a fixed effect that captures whether actors’ initial self-protective rule use predicts their satisfaction trajectories, (6) the two-way interaction between time and risk, a fixed effect that captures whether actors’ initial risk exposure predicts their satisfaction trajectories, (7) the two-way interaction between actors’ initial self-protective rule use and risk, a fixed effect that captures whether exercising self-protection has different effects on initial satisfaction in low-than high-risk relationships, and (8) the predicted three-way interaction between actors’ initial self-protective rule use, risk, and time, a fixed effect that taps the contextual effects of self-protection on satisfaction trajectories. To distinguish the effects of rule use from its constituent behaviors, we also added: (9) actors’ initial level of self-protective behavior (centered) and its interaction with time, fixed effects that capture whether actors’ initial self-protective behavior predicts satisfaction trajectories. Finally, we also estimated error terms that captures how much actors’ average satisfaction varies from the overall average and their own average across time.vii

Table 3 lists the coefficients for this model. It reveals the predicted three-way interaction between actors’ initial practice of self-protective “if-then” rule habits, risk-climate, and time in predicting their satisfaction trajectories. Further analyses utilizing the individual risk indicators also revealed 3-way interactions; therefore, we only report the composite index of risk.

Table 3.

Predicting Declines in Satisfaction from Practicing Self-Protection and the Composite Risk Index

| Predictor | b (SE) | z |

|---|---|---|

| Quantifying Satisfaction’s Trajectory | ||

| Intercept | 7.17W 7.02M |

-- |

| Time | −.128 (.011) | −11.64*** |

| Testing the Hypothesized Contextual Effects of Self-Protection | ||

| Actor’s self-protective rules | −.615 (.719) | −0.86 |

| Actor’s self-protective rules by time | −.169 (.126) | −1.34 |

| Actor’s risk | −.210 (.040) | −5.25*** |

| Actor’s risk by time | −.001 (.007) | −0.14 |

| Actor’s self-protective rules by risk | −.375 (.381) | −0.98 |

| Actor’s self-protective rules by risk by time | .268 (.069) | 3.88** |

| Control Variables | ||

| Actor’s self-protective behavior | −.274 (.059) | −4.64*** |

| Actor’s self-protective behavior by time | −.009 (.011) | −0.82 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Next we decomposed the three-way interaction into its component two-way interactions. The fit between self-protection practices and relationship-risk (high vs. low) can be evaluated from two perspectives. First, does the self-protective nature of the “if-then” rules people practice change the effects of the environment (i.e., the risk by time interaction predicting satisfaction for people who self-protect more vs. less)? Second, does the environment allow the strategy to work (i.e., the self-protection practice by time interaction in low-versus high-risk contexts)?

Both sets of 2-ways revealed the importance of fit. The two-way risk-climate by time interactions were opposite and significant for people who initially practiced less self-protection, b = −.032, SE = .012, z = −2.67, p < .01, and people who initially practiced more self-protection, b = .029, SE = .010, z = 2.90, p < .01. The two-way self-protective habits by time interactions were also opposite and at least marginally significant for people in low-risk, b = −.540, SE = .187, z = −2.89, p < .01, and high risk relationships, b = .203, SE = .124, z = 1.64, p = .10.

Figures 3A and 3B illustrate the effects of the fit between self-protection practices and the risk climate on changes in satisfaction. It highlights the effects of risk-climate on satisfaction’s decline for people who practiced low versus high levels of self-protection initially (one standard deviation below and above the mean, controlling for all other variables in the model). The simple effects of time revealed the expected effects of fit. When people practiced less self-protection, satisfaction declined more in high, b = −.152, SE =.024, z = −6.33, p < .001, than low-risk relationships, b = −.064, SE =.025, z = −2.56, p < .05. But, when people practiced greater self-protection, satisfaction declined more in low, b = −.187, SE =.026, z = −7.19, p < .001, than high risk relationships, b = −.106, SE =.018, z = −5.89, p < .001. Conversely, in low-risk relationships, satisfaction declined more when people were overly self-protective than when they were less cautious. But, in high-risk relationships, satisfaction declined more when people practiced less self-protection than when they were more appropriately cautious.viii, ix, x, xi

Figure 3.

Figure 3A and 3B. Declines in Satisfaction as a Function of Risk for People Who Practice More or Less Self-Protection

Testing The Moderated Mediation Model

Our final set of analyses test for the pattern of moderated mediation specified in Figure 2. As a first step in testing this hypothesis, we obtained indices of each person’s change in satisfaction over time. To do this, we obtained the residual slopes for time from a multi-level model predicting satisfaction from an intercept term, the random effect of time, and the appropriate error terms. The residual slopes capture how much each person’s change in satisfaction departed from the average decline (i.e., greater than average decline, less than average decline). We then used these indices of each person’s satisfaction trajectory as outcome variables in our moderated mediation model.

Figure 4 presents the SEM model we utilized to test for moderated mediation, as specified in the procedures described by Preacher et al. (2007). We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test this hypothesis because SEM accommodates the dyadic structure of data from two partners and allows the estimation of pooled effects across gender (Kenny; 1996; Kenny & Cook, 1999). We expected less trusting people to self-protect more. When caution was inappropriate to the relationship risks, we also expected exercising greater self-protection to put people who were initially less trusting at greater risk for declines in satisfaction.

Figure 4.

Estimating the Moderated Mediation Model

Four paths in Figure 4 are central to testing these hypotheses. Paths a and a′ index the association between actors’ trust and tendency to practice self-protection. Paths b and b′ index the association between actors’ self-protective rule habits and changes in satisfaction. Paths c and c′index the interactive effects of self-protective habits and risk climate on changes in satisfaction (i.e., an analogue to the multilevel 3-way interaction between time, self-protective habits, and risk in Table 3). Paths d and d′ index the direct effects of actors’ trust on changes in satisfaction. We also estimated correlations among the exogenous variables, the covariance between the risk moderator (Paths e and e′) and the error term for self-protection, and the covariance between the interaction and the error term for self-protection (Preacher et al., 2007).

We also estimated two further effects for control purposes. We included the composite indices of self-protective behavior (Paths f and f′) to distinguish the effects of practicing self-protective “if-then” rules from the constituent behaviors. We also estimated the direct effects of partners’ trust on the actors’ satisfaction (paths g and g′) to distinguish the effects of practicing self-protective rules oneself from any potential costs attached to possessing a less trusting partner. We also estimated cross-gender covariances between the error terms for the mediator (i.e., men’s and women’s self-protective rule use) and between the error terms for the outcome variable (i.e., men’s and women’s changes in satisfaction).xii

Table 4 presents the coefficients. Paths a and a′ and c and c′, central to the moderated mediation hypothesis, were significant. People who trusted less in their partner’s regard practiced more self-protective “if-then” rules (Paths a and a′). The interaction between self-protection and risk was also significant (Paths c and c′), duplicating the 3-way interaction obtained in the multilevel model (see Table 3). We expected practicing self-protection to mediate the association between trust and changes in satisfaction in low-risk relationships, but not in high-risk relationships. This means that the conditional indirect effect of trust to self-protection to changes in satisfaction should be significant when relationship are low in risk, but not when the relationship is high in risk. To test the significance of this conditional indirect effect, we utilized normal-theory standard errors as specified by Preacher et al. (2007, Table 1, Model 3). When risk was relatively low (i.e., one standard deviation below the mean), the conditional indirect effect of trust to self-protection to changes in satisfaction was significant, f (θ|X) = .76, z = 2.15, p < .05. However, this conditional indirect effect was not significant when the risk was relatively high, f (θ|X) = .07, z = 0.58.

Table 4.

The moderated-mediation model with the composite risk index.

| Predictor | standardized b | z |

|---|---|---|

| Predicting Practicing Self-Protective Rules | ||

| Actors’ self-protective behavior | .21 | 3.58*** |

| Actors’ trust | −.14 | −2.44* |

| Predicting Changes in Satisfaction | ||

| Actors’ self-protective “if-then” rules | −.20 | −3.58*** |

| Actors’ risk | −.08 | −2.22* |

| Actors’ self-protective “if-then” rules by risk | .20 | 4.98*** |

| Actors’ trust | .07W −.10M |

1.17W −1.93+M |

| Partners’ trust | .18 | 3.83** |

| Actors’ self-protective behavior | −.12 | −2.15* |

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, χ2(13, N = 193) = 7.10, ns.

Exploring An Alternate Model

Because trust and self-protection were measured concurrently, this suggests an alternate causal model. Specifically, when relationship risks are low, being less trusting might mediate the association between one’s initial tendency to practice self-protective “if-then” rules and one’s subsequent satisfaction. To test this possibility, we conducted a moderated mediation model in which we switched the placement of trust and self-protection in Figure 4. Estimating this model revealed that self-protective practices predicted trust. However, the conditional indirect effect of self-protection to trust on changes in satisfaction was not significant when risk was relatively low, f (θ|X) = −3.80, z = −1.19, or high, f (θ|X) = 3.82, z = 1.41.

Discussion

The findings suggest that Russell’s romantic admonition requires some revision. Caution itself is not fatal to true happiness. Instead, practicing self-protective rule habits in circumstances that do not warrant caution precipitates steep declines in satisfaction. Thus, it is being cautious to a fault that may be fatal to true happiness.

Caution in Context: Predicting Marital Satisfaction Trajectories

The motivation-management model of mutual responsiveness asserts that partners can practice self-protection by applying three “if-then” rules (Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011). Ron can ignore or push Gayle away when he fears being rejected by her (i.e., a stronger reduce-own-dependence rule); he can take concrete steps to make her rely on him when he feels inferior to her (i.e., a stronger promote-partner-dependence rule), or he can value her less when she interferes with his personal goals (i.e., a weaker justify-own-costs rule). This model further assumes that people can develop “if-then” habits to self-protect that are more or less appropriate to the risks of non-responsiveness that they encounter within the relationship. The contextual model of self-protection detailed in Figure 2 builds on this logic. This model assumes that being less trusting elicits self-protective caution that undermines satisfaction when caution is not appropriate to the relationship’s risks. Overall, the results provide strong initial support for the three hypotheses subsumed within the model.

First, the fit between self-protection practices and the relationship’s risk climate predicted the severity of the decline in satisfaction (Paths B X C). When people practiced greater self-protection, satisfaction declined more in low-risk relationships (where being cautious is a poor fit) than in high-risk relationships (where being cautious is a good fit). Indeed, the counterintuitive nature of this finding – that people in low-risk relationships ended up worse off than people in high-risk relationships – powerfully illustrates the importance of fitting self-protective practices to risk circumstances. In contrast, when people practiced less self-protection, satisfaction declined more in high-risk relationships (where not being cautious is a poor fit) than in low-risk relationships (where not being cautious is a good fit). Second, people who trusted less in their partner’s regard practiced greater self-protection in their daily interactions (Path A). Third, when caution was less appropriate to the relationship risks, exercising greater self-protection left less trusting people vulnerable to steeper declines in satisfaction. Specifically, exercising greater self-protection (i.e., the mediator) explained the association between trusting less in the partner’s responsiveness (i.e., the cause) and declines in satisfaction (i.e., the effect) in low, but not high, risk relationships (i.e., the moderator).

The current findings have several strengths. We utilized people’s ongoing, real-life interactions to index how often they practiced self-protective “if-then” rules. The diary methodology does not require people to understand the contingencies that govern their behavior. Instead, it assesses these contingencies bottom-up from the feelings and behaviors people evidence from one day to the next. Despite the subtlety of this measure, we predicted the trajectory of satisfaction over a period of three years from the self-protective rules partners followed in a two-week period in the initial months of marriage. Furthermore, we observed the moderating effect of risk utilizing a risk composite that included the partner’s self-reported personal vulnerability. Finally, existing experimental research suggests that the reduce-own-dependence, promote-partner-dependence, and justify-own-costs rules can control interaction without the intercession of consciousness (see Murray & Holmes, 2009; 2011 for reviews). In this light, the results raise the possibility that implicit procedural features of people’s working models of their particular relationship may help control how satisfying (or dissatisfying) their marriages become (Baldwin, 1992).

Nonetheless, the current findings have a limitation: The data are correlational. Because we assessed the concurrent association between trust and self-protection, it might be the case that being self-protective predisposes people to be more distrusting (rather than vice versa). Although we cannot rule out this possibility, we estimated an alternative moderated-mediation model in which trust mediated the association between self-protection and declines in satisfaction. However, we did not find significant evidence of moderated mediation, rendering this alternative model less plausible. Further, experimental research also suggests that being less trusting increases self-protection. For instance, people primed with a time when their partner disappointed them automatically distance from their partner (Murray et al., 2008). People induced to question their value relative to their partner also self-protectively increase their efforts to put their partner in their debt (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009).

Examining long-term changes in satisfaction provides the best means of examining causation naturalistically. But even longitudinal data cannot rule out the possibility that a third variable might account for the effects of exercising self-protective “if-then” rules. However, we can rule out some of the most salient alternatives. First, the effects of practicing self-protective “if-then” contingencies in one’s behavior did not simply capture the effects of engaging in the constituent behaviors because we controlled for overall levels of self-protective behavior in all of our analyses. Second, further analyses revealed that the effects of practicing self-protection did not simply capture the effects of being more personally vulnerable to rejection oneself. In these analyses, we added the main and interactive effects of the actor’s personal vulnerability to Equations 3 and 4. We did not find any significant moderating effects for the actors’ rejection sensitivity, but the hypothesized moderating effects of risk climate remained significant.

Because trust is so often a projection of one’s own self-worth, it does raise a further potential alternative explanation for the effects. People egocentrically use their feelings about themselves as a benchmark to gauge their partner’s regard for them (Griffin & Ross, 1991; Murray et al., 2000). Consequently, the apparent effects might simply capture the direct and mediated effects of people’s own views about their interpersonal worth. Because we assessed people’s self-perceptions on the interpersonal qualities scale (Murray et al., 2000), we could examine this possibility. In a further set of analyses, we included self-perceptions on the IQS as a control variable in the moderated mediation model depicted in Figure 4. These analyses revealed that self-perceptions did not significantly predict self-protection practices or changes in satisfaction over time. However, trust continued to predict self-protective practices and the interaction between trust and risk remained significant predicting changes in satisfaction. Finally, we estimated a further moderated mediation model using reports on a scale that captures perceptions of the partner’s regard for one’s traits, an indirect measure of trust we have utilized in past research (Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003; Murray, Griffin, Rose & Bellavia, 2003). Using this alternative measure of trust, we still found the predicted and significant pattern of moderated mediation. Of course, our findings are limited to the specific measures we utilized to index each “if-then” rule. Although we utilized these measures because of their established validity (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009; Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003; Murray, Holmes et al., 2009; Murray et al., 2010), future research might examine alternate ways of measuring each “if-then.”

The satisfaction trajectories illustrated in Figures 3A and 3B did reveal one seemingly paradoxical aspect to our findings. In low-risk relationships, practicing high levels of self-protection substantially accelerated declines in satisfaction (relative to the declines evidenced for those who were less cautious). In high-risk relationships, being less self-protective also sped declines in satisfaction relative to being more self-protective. However, this particular 2-way interaction was less pronounced. This asymmetry in the three-way interaction may capture asymmetries that are basic to interdependence. First, incompatible preferences make it disproportionately harder to foster pleasing interaction patterns independent of the “if-then” rules that partners have at their disposal (Kelley, 1979). Second, there is more to be lost in being risk-averse than there is to be lost in being risk-seeking (Holmes & Rempel, 1989; Murray & Holmes, 2011). Consider the paradox that is basic to the growth of trust: People cannot obtain concrete evidence that their partner is trustworthy without first giving their partner the opportunity to disappoint them (Holmes & Rempel, 1989; Simpson, 2007). To gain objective reason to trust in Gayle, Ron needs to risk relying on her in diagnostic situations where she is strongly tempted to be selfish because her sacrifices then attest to her caring for him (Holmes, 1981; Kelley, 1979). Therefore, in high-risk relationships, being less self-protective may not compound satisfaction’s decline as significantly because risking connection yields rewards, such as greater trust in the partner’s caring, often enough to compensate for any potential costs.

The central premise of our model – that self-protection puts relationships at risk when caution is not commensurate with the encountered risks – complements other contextual analyses of relationship dynamics (McNulty, 2010). For example, people who are naively optimistic – that is, people who blame their partner for problems while nonetheless expecting their partner to behave perfectly in the future – experience steeper declines in satisfaction than people who are more realistic (McNulty & Karney, 2004). Newlyweds who make inappropriately charitable attributions for serious problems also experience steeper declines in satisfaction than newlyweds who make less charitable attributions (McNulty et al., 2008). Similarly, newlyweds who directly engage severe problems by communicating blame are more likely to stay satisfied than newlyweds who communicate less blame (McNulty & Russell, 2010).

People who self-protect despite facing little risk may experience steep declines in satisfaction because being cautious to a fault forfeits real opportunities for positive, satisfaction-sustaining, interactions. Over the newlywed years, partners shift their activities from leisure, fun and sex to the drudgery of household chores and the stresses of parenting. Not surprisingly, satisfaction declines over this same period (Doss, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, 2009; Karney & Bradbury, 1997; Huston et al., 1991; Kurdek, 1999). In this progressively negative behavioral landscape, maintaining a base of positive interactions becomes central to sustained satisfaction (Aron, Norman, Aron, McKenna, & Heyman, 2000; Gottman, Ryan, Carrere, & Erley, 2002).

However, being unduly self-protective may make it difficult to accrue the positive experiences low-risk relationships can afford (Murray & Holmes, 2011). For example, by valuing Harry less when he thwarts her goals, Sally erodes her motivation to make sacrifices for him (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009), responsive behaviors that are key for continued satisfaction (Reis et al., 2004). By pushing Harry away when he seems the slightest bit critical, Sally also limits his opportunities to prove how supportive and understanding he can be (Murray et al., 2008), eroding intimacy (Reis & Shaver, 1988). In contrast, being judicious and self-protective in relatively high-risk relationships might make it easier to avoid negative experiences that come with incompatible preferences or vulnerable partners. For instance, avoiding Gayle and not soliciting her support when she is angry might help Ron avoid conflicts that would only escalate into negative reciprocity cycles (Gottman, 1994). Thus, exercising a level of caution that is appropriate to the risks may be the best means of ensuring that positive interactions continue to outweigh negative ones as interdependence increases.

Conclusion

Interdependent relationships routinely put the goal to connect to the partner in conflict with the goal to self-protect against the partner’s potential rejection and non-responsiveness (Murray et al., 2006). In this context, exercising self-protective caution is prudent when it is appropriate to the likely risks. However, being in the habit of self-protecting against imagined risks predisposes people who are less trusting to precipitous declines in satisfaction. Thus, it is being unduly or inappropriately cautious that proves fatal to continued happiness.

Highlights.

When does practicing self-protective if-then rules erode marital satisfaction?

Fit between “if-then” rules and risk forecast newlywed declines in satisfaction.

When self-protected more, satisfaction declined more in low-risk relationships.

When self-protected less, satisfaction declined more in high-risk relationships.

In low-risk relationships, less trust predicted caution and declines in satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maya Aloni, Lisa Jaremka, Sadie Leder, Cara O’Donnell and numerous undergraduate research assistants for their help with this research. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 60105-08) to S. Murray.

Footnotes

Because moving away from the partner means that one is not moving toward the partner in any specific situation, measuring the “reduce-own-dependence” rule is sufficient to capture self-protection (Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003; Murray, Holmes & Pinkus, 2010).

In prior research, we used the daily diary data in this same sample of newlyweds to document the prevalence and function of the “promote-partner-dependence” (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009) and “justify-own-costs” rules (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). These data revealed that people responded to feeling acutely inferior to their partner by doing more instrumental favors for their partner on subsequent days; doing such favors then increased their partner’s commitment on the next day (i.e., the “promote-partner-dependence” rule, Murray, Aloni et al. (2009)). High self-esteem people also responded to the costs imposed by their partner infringing on their goals by valuing their partner more on subsequent days (i.e., the “justify-own-costs” rule, Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). On days after people compensated for costs, they also treated their partner more responsively. Moreover, compensating for experienced costs protected high self-esteem people against declines in satisfaction over 12 months (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009).

The current paper builds on these prior findings in several ways. This paper is the first to test the hypotheses that: (1) newlyweds who report less trust in their partner’s responsiveness practice more self-protective “if-then” rules, (2) the match between self-protective practices and relationship risk predicts the trajectory satisfaction takes over the first three years of marriage, and (3) that being less trusting erodes satisfaction because it fosters misapplying the “if-then” rules for self-protection and connection. In prior longitudinal research, we also utilized this newlywed sample to test hypotheses that are conceptually separate from those advanced here. We published one paper relating unrealistic idealization at the point of marriage to satisfaction trajectories over three years (Murray et al., 2011). This paper revealed that unrealistically viewing one’s romantic partner as resembling one’s ideals protected against declines in satisfaction. The measure of unrealistic idealization utilized in Murray et al. (2011) is statistically independent of the measures of self-protection utilized in the current study. In one further paper utilizing a subset of the newlywed sample, we utilized the indices of “reduce-own-dependence” and “justify-own-costs” utilized in the current study to predict automatic attitudes toward the partner after four years of marriage. The measure of automatic partner attitudes was not significantly associated with the satisfaction trajectories examined in the current study (Murray, Holmes & Pinkus, 2010). In sum, the current findings represent conceptually and empirically distinct effects; prior papers did not examine “if-then” rule use as a function of trust, nor did they predict satisfaction trajectories over 3 years from “if-then” rule use and risk.

On any given day, we had no expectation that participants who reported engaging in one type of behavior would necessarily engage in other such behaviors. For this reason, we do not report internal consistencies for the behavior/event categories (McNulty & Russell, 2010).

We utilize cross-day effects to index each “if-then” rule because indexing how today affects tomorrow better ensures that the “IF” did actually proceed rather than follow the “THEN” (Murray, Aloni et al., 2009; Murray, Bellavia et al., 2003; Murray, Holmes et al., 2009).

Prior research established the discriminant validity of the “if-then” rules. Feeling inferior to the partner specifically elicits the tendency to engage in communal, dependence-promoting behaviors; it does not elicit the general tendency to behave in either accepting (e.g., being affectionate) or rejecting ways (e.g., yelling at the partner, Murray et al., 2009). Feeling less accepted by the partner elicits the tendency to engage in more rejecting behaviors (Murray et al., 2003); it does not elicit the tendency to engage in communal behaviors, Murray et al., 2009).

Also, the perception that one’s partner has thwarted one’s goals elicits the compensatory tendency to value one’s partner more; however, the perception that one’s partner has behaved in hostile or rejecting ways does not elicit compensatory valuing (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009).

We present separate coefficients for men and women when the deviance tests for separate coefficients were significant, χ2 > 3.84, p < .05.

We specified the lagged effect of time as a fixed rather than a random effect because focused tests of cross-level interactions have greater power to detect between person-variation in slopes than the omnibus deviance test of random slopes (LaHuis & Ferguson, 2009; Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

Although not central to our model, we also estimated further multilevel models in which we examined whether Ron’s tendency to self-protect (in either low- or high-risk relationships) predicted declines in Gayle’s satisfaction. We did not find any significant partner effects predicting changes in satisfaction. Moreover, the three-way interaction between the actor’s self-protection, risk, and time predicting the actor’s satisfaction trajectory remained significant, b = .277, SE = .071, z = 3.90, p < .01.

We also estimated further models where we included the three-way interaction between average levels of self-protective behavior (i.e., the composite of the intercepts), risk, and time (as well as the appropriate two-way interactions). The hypothesized interaction involving self-protective rule use (i.e., the composite of the slopes) remained significant, b = .287, SE = .069, z = 4.16, p < .01.

We found generally parallel effects on satisfaction trajectories for each of the component indices. The 3-way justify-own-costs by risk by time interaction was significant, b = −.322, SE =.096, z = −3.35, p < .01, the 3-way reduce-own-dependence by risk by time interaction was significant, b = .247, SE =.117, z = 2.11, p < .05, and the 3-way promote-partner-dependence by risk by time interaction was significant for men, b = 1.135, SE =.472, z = 2.40, p < .001, but not women, b = −1.126, SE =.651, z = −1.73.

In the present sample, global reports of conflict were moderately negatively reported with initial satisfaction (see Table 2), raising the possibility that this measure might not provide the most objective barometer of risk. Accordingly, we conducted a further set of analyses where we utilized actors’ average reports of arguments during the diary period in place of the global conflict measure in the overall risk composite. This analysis also yielded the predicted and significant 3-way time by self-protective habits by risk interaction predicting changes in satisfaction, b = .199, SE = .069, z = 2.88, p < .01.

We also estimated cross-gender correlations between the exogenous variables and the error terms for the mediator and the outcome variables. Specifically, we estimated the covariance between the value of the risk moderator for one partner and its interaction with self-protective “if-then” rule use and the other partner’s tendency to exercise self-protection, between one partner’s trust, average self-protective behavior, and the other partner’s self-protective “if-then” rule use, and between one partner’s average self-protection and the other partner’s changes in satisfaction. We also estimated a further model where we modeled these associations as direct paths rather than as covariance paths. That is, we estimated a model that included all possible partner effects. The results of this model revealed that none of the partner effects were significant and that all of the significant actor effects detailed in Table 4 remained significant.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sandra L. Murray, University at Buffalo, State University of New York

John G. Holmes, University of Waterloo

Jaye L. Derrick, Research Institute on Addictions, Buffalo, NY

Brianna Harris, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Dale W. Griffin, University of British Columbia

Rebecca T. Pinkus, University of Western Sydney

References

- Aron A, Norman CC, Aron EN, McKenna C, Heyman R. Couples’ shared participation in novel and arousing activities and experienced relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;69:1102–1112. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MW. Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:461–484. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Boldry J, Kashy DA. Perceptions of conflict and support in romantic relationships: The role of attachment anxiety. Journal of Personality and social Psychology. 2005;88:510–531. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Simpson JA, Boldry JG, Rubin H. Trust, variability in relationship evaluations and relationship processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:14–31. doi: 10.1037/a0019714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Clark MS, Grote NK. Why aren’t indices of relationship costs always negatively related to indices of relationship quality? Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:2–17. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Feeney BC. Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;87:363–383. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos A, Riefler P, Roth KP. Advancing formative measurement models: Journal of Business Research. 2008;61:1203–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos A, Winklhofer HM. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research. 2001;38:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. The effect of the transition to parenthood on relationship quality: An 8-year prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96:601–619. doi: 10.1037/a0013969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:545–560. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ, Campbell WK. Self-control and accommodation in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:263–277. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJO, Kerr PSG. Through the eyes of love: Reality and illusion in intimate relationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:627–658. doi: 10.1037/a0019792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne FM, Lydon JE. Bias and accuracy in close relationships: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:322–338. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H, Rasbash J, Plewis I, Draper D, Brown W, Yang M, Woodhouse G, Healy M. Multilevel Models Project. Institute of Education; University of London: 1998. A user’s guide to MlwiN. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Ryan KD, Carrere S, Erley AM. Toward a scientifically based marital therapy. In: Liddle HA, Santisteban DA, Levant RF, Gray JH, editors. Family psychology: Science-based interventions. Washington DC: APA; 2002. pp. 124–174. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:430–445. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DW, Ross L. Subjective construal, social inference and human misunderstanding. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1991;24:319–359. [Google Scholar]