To the Editor

Of patients treated with hemodialysis, 50% report pain, and 83% rate it moderate to severe.1 The etiology is multifactorial, often related to comorbid conditions such as peripheral vascular disease and osteoarthritis; complications of kidney failure such as osteodystrophy, calciphylaxis, and peripheral neuropathy; and events related to the dialysis procedure, such as needling, dialysate infusion, and osmolar shift cramps.1,2 Because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs adversely affect kidney function in earlier stages of CKD, opioids may be perceived as the preferred analgesic agents in this population. However, little is known about the safety or effectiveness of opioids in patients receiving dialysis. To inform future research and quality improvement activities, we sought to quantify the magnitude of opioid use in the US hemodialysis population.

We used data from the US Renal Data System, a registry that includes all patients in the Medicare ESRD program and provides detailed demographic and health care utilization data. We identified all patients 18 years and older receiving hemodialysis between July 1 and December 31, 2008, with Medicare as primary payer and Parts A, B, and D coverage. Incident patients were required to have initiated dialysis therapy at least 90 days prior to cohort entry to ensure stability in dialysis therapy and processing of Medicare eligibility/enrollment forms. Information on opioid use was ascertained from Medicare Part D prescription claims. Analysis was restricted to opioid prescriptions for pain. Opioids used in cough suppressants were excluded. We calculated the proportion of patients receiving at least one opioid prescription, overall and within patient subgroups. Using similar eligibility criteria, a separate analysis was performed for a 30-month study period (July 2006 through December 2008) to calculate the quarterly proportion of patients receiving at least one opioid prescription. For each quarter, continuous eligibility was required for the entire quarter. Patients were censored from subsequent quarters at the earliest of end of continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A, B, and D; loss to follow-up; kidney transplantation; death; or administrative censoring on December 31, 2008.

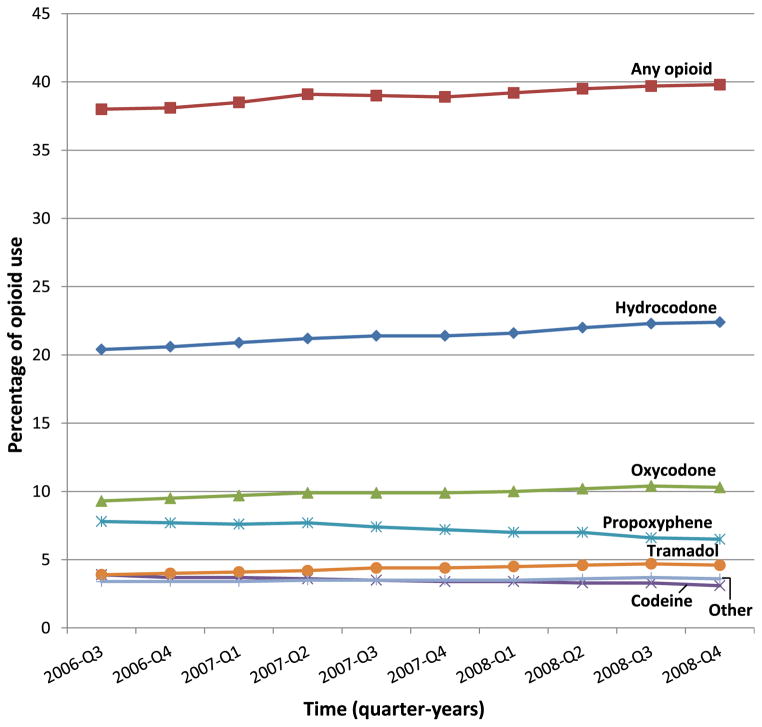

A total of 145,573 eligible patients received hemodialysis during the 6-month study period of July through December 2008. The study population was middle-aged (mean, 60 years), 52% men, 50% white, 44% black, and 7% low income subsidy status. The 2 most common causes of kidney failure were diabetes (45%) and hypertension (30%). Fifty percent (n = 73,433) of patients were prescribed at least one opioid, and there were 315,856 opioid prescriptions. Hydrocodone, oxycodone, and propoxyphene were prescribed to 30%, 14%, and 10% of the study population, respectively. Opioid use was higher among patients of younger age, female sex, black or white race, and without low income subsidy status (Table 1). Opioid use also varied by primary cause of ESRD (diabetes, 52%; hypertension, 48%; glomerulonephritis, 52%) and years on dialysis therapy (<1, 53%; 1–2, 49%; 3–5, 49%; 6–10, 52%; >10, 55%). During the 30-month study period from July 2006 through December 2008, the study population received almost 1.6 million opioid prescriptions. Opioid use increased from quarter 3 of 2006 (38%) to quarter 4 of 2008 (40%). Use of stronger opioids increased, with hydrocodone use increasing from 20% to 22% and oxycodone use increasing from 9% to 10%. Use of weaker opioids decreased, with propoxyphene use declining from 8% to 7% and codeine use declining from 4% to 3%. Tramadol was the exception among weaker opioids, with use increasing from 4% to 5% (Fig 1).

Table 1.

Percentage of Study Population With Opioid Use, by Opioid Type

| Hydrocodone (n = 43,658) | Oxycodone (n = 20,956) | Propoxyphene (n = 14,251) | Other (n = 22,345) | Anya (n = 73,433) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| <45 y | 35.5 | 19.1 | 8.4 | 16.4 | 54.6 |

| 45–64 y | 32.7 | 16.7 | 9.5 | 16.0 | 53.6 |

| 65–84 y | 25.3 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 14.3 | 45.9 |

| ≥85 y | 19.2 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 13.4 | 39.4 |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 32.0 | 14.5 | 12.6 | 18.1 | 55.2 |

| Male | 28.1 | 14.3 | 7.2 | 12.8 | 46.0 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 30.4 | 13.0 | 10.4 | 15.1 | 50.6 |

| Black | 30.8 | 16.7 | 9.7 | 16.0 | 52.2 |

| Asian | 17.4 | 6.3 | 3.3 | 10.0 | 29.8 |

| Low income subsidy | |||||

| No | 30.2 | 14.6 | 9.8 | 15.7 | 50.9 |

| Yes | 27.0 | 11.6 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 43.9 |

Note: Data from July to December 2008.

Defined as receiving at least one opioid prescription for pain.

Figure 1.

Quarterly opioid use among US dialysis patients, July 2006 to December 2008. Opioid use was defined as receiving at least one opioid prescription for pain.

We document widespread use (38%-50%) of opioids in the US hemodialysis population. In comparison, previous US studies have reported much lower opioid use in the general (17%-18%)3 and veteran (33%)4 populations. Previous studies of the long-term dialysis population have reported lower use (5%-21%), but these estimates were based on self-report and medical chart review, which may underestimate prevalence.5 Over time, use of stronger opioids has increased. With the removal of propoxyphene from the US market in November 2010,6 the trend toward more potent opioid use may increase further. Opioid use was characterized by considerable variation across demographic and clinical characteristics. Conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the clinical appropriateness of opioid prescribing in this population because of a lack of data for pain severity. We also did not consider duration or dose of opioids. A final limitation of the study is that the data represent filled prescriptions covered by Medicare Part D, rather than actual opioid consumption. Because patients may pay for prescriptions out of pocket or use another pharmacy benefit, we may have underestimated the true prevalence of opioid use. Given increasing concerns about the safety of opioids in vulnerable groups such as the elderly,7 research is needed to better understand the safety and effectiveness of opioids in dialysis patients, who frequently have numerous concurrent medications and comorbid conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Lily Wang for programming work.

Support: None.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr Brookhart reports receiving grant support from Amgen; serving on scientific advisory boards for Pfizer, Amgen, and Merck (honoraria declined, donated, or given to institution); and serving as a consultant to DaVita Clinical Research, Crimson Health, and World Health Information Consultants. Dr Kshirsagar reports serving on an advisory board for Fresenius. Ms Butler declares that she has no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Davison SN. Pain in hemodialysis patients: prevalence, cause, severity, and management. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:1239–1247. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carreon M, Fried LF, Palevsky PM, Kimmel PL, Arnold RM, Weisbord SD. Clinical correlates and treatment of bone/joint pain and difficulty with sexual arousal in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2008;12:268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2008.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RE, Sampson TJ, Kalilani L, Wurzelmann JI, Janning SW. Epidemiology of opioid pharmacy claims in the United States. J Opioid Manag. 2008;4:145–152. doi: 10.5055/jom.2008.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark JD. Chronic pain prevalence and analgesic prescribing in a general medical population. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:131–137. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyne A, Rai R, Cuerden M, Clark WF, Suri RS. Opioid and benzodiazepine use in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:326–333. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04770610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed June 24, 2013.];Propoxyphene: withdrawal—risk of cardiac toxicity. 2010 http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm234389.htm.

- 7.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, et al. The comparative safety of opioids for nonmalignant pain in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1979–1986. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]