Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate feasibility, acceptability, continuation, and trough serum levels following self-administration of subcutaneous (SC) depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA).

Study Design

Women presenting to a family planning clinic to initiate, restart, or continue DMPA were offered study entry. Participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to self or clinician administered SC DMPA 104mg. Those randomized to self-administration were taught to self-inject and were supervised in performing the initial injection; they received printed instructions and a supply of contraceptive injections for home use. Participants randomized to clinician administration received usual care. Continued DMPA use was assessed by self-report and trough MPA levels at six and twelve months.

Results

250 women were invited to participate and 137 (55%) enrolled. Of these, 91 were allocated to self-administration, and 90/91 were able to correctly self-administer SC DMPA. Eighty-seven percent completed follow-up. DMPA use at one year was 71% for the self-administration group and 63% for the clinic group (p=0.47). Uninterrupted DMPA use was 47% and 48% for the self and clinic administration groups at one year (p = 0.70), respectively. Serum analyses confirmed similar mean DMPA levels in both groups and therapeutic trough levels in all participants.

Conclusions

Sixty-three percent of women approached were interested in trying self-administration of DMPA, even in the context of a randomized trial, and nearly all eligible for enrollment were successful at doing so. Self-administration and clinic administration resulted in similar continuation rates and similar DMPA serum levels. Self-administration of SC-DMPA is feasible, and may be an attractive alternative for many women.

Keywords: Contraception, injectable, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, self-administration

INTRODUCTION

Many women are at high risk of becoming unintentionally pregnant each year because of a gap in contraceptive use [1]. The shorter effective timeframe and need for continued provider intervention sets depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) apart from other longer acting contraceptives. Many women discontinue DMPA secondary to unpredictable bleeding, and difficulty in access is also a problem with only 27 – 53% of women continuing at one year [1–4]. The advent of a subcutaneous (SC) formulation of DMPA can alleviate the need to return to clinic for subsequent injections and makes administration outside of the clinical setting possible. While this formulation is not currently labeled for self-administration in the U.S., many subcutaneously delivered medications including enoxaparin, heparin, insulin, and gonadotropins frequently are self-administered. In addition, pilot studies evaluating self-administration of injectable contraceptives showed favorable results with both patient willingness and ability to self-inject [5–8].

MATERIALS and METHODS

This clinical trial compared continuation of DMPA between women randomized to self-administration or clinic administration of SC DMPA. Participant related activities were conducted between 2010 and 2011 in New York City. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all patients gave informed consent. Eligible women were aged 18 or greater, seeking DMPA for contraception, and available for follow up for one year. We excluded women with medical contraindications to the use of DMPA based on the World Health Organization Medical Eligibility Criteria, enrolling only women in category 1 or 2 [9]. We also specifically excluded women with a suspected or confirmed pregnancy or desire for pregnancy within one year. Procedures for enrollment, instruction, and observation for DMPA self-administration were successfully piloted with the first five eligible participants.

We stratified participants based on never, current, or past use of DMPA and randomized them to self or clinic administration. The sequence for the 2:1 (self vs. clinic administration) treatment allocation was determined using a computerized random-number generator in blocks of six. An investigator not involved with participant contact generated the allocation schedule, which was concealed until after informed consent. Group assignments for each stratum were placed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. After informed consent and screening were completed, the next envelope in the sequence was opened and participants were enrolled by the study coordinator.

All enrolled participants answered a baseline questionnaire to assess demographic and reproductive characteristics, past contraceptive practices, and future pregnancy plans. Participants initiated DMPA on the day of the enrollment visit, including continuing users, women within days 1–5 of the menstrual cycle, and all others, who received SC DMPA per Quickstart protocol [10]. Those randomized to the self-administration arm were taught to self-inject by the study coordinator using modified illustrations from Instructions for the use of depo-subQ provera 104 [11]. The participant performed the initial injection in the abdomen or thigh under supervision, and if deemed acceptable, was given prepackaged SC DMPA (Depo-subQ Provera 104®, Pfizer, New York) containing a prefilled syringe and needle to use at home, along with alcohol pads, a bandage, a urine pregnancy test, and a DMPA calendar giving dates for the next injection. Participants beyond day 1–5 of the menstrual cycle at enrollment were instructed to use the urine pregnancy test in 3 weeks; the research coordinator contacted each of these women to ensure that the pregnancy test was taken and that the result was negative [12]. Participants received instructions on how to restart DMPA outside of the usual 14 week dosing window under the Quickstart protocol if temporary discontinuation occurred during the study. Each participant received a sharps disposal canister and instructions in safe needle disposal.

All participants received appointments for revisits at 6 and 12 months, scheduled immediately prior to the anticipated date of the third and fifth contraceptive injections. Participants randomized to clinic administration received routine appointments for their next injections, and clinic charts were reviewed to verify administration of DMPA. At six months, those in the self-administration group were reevaluated for ability to self-inject, and received additional prepackaged SC DMPA for home administration. At the twelve month exit interview participants responded to questions regarding continuation, satisfaction, and administration. At both the six and twelve month visits, we collected a blood specimen to measure medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) levels. There were no additional costs to the participants for SC DMPA use; however, participants were compensated up to $120 for complete study participation.

Specimens were centrifuged, and aliquots were stored at −80°C until analysis. MPA was measured in serum by an in-house developed Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MSMS) assay using an Acquity UPLC and a Xevo TQ-S Mass Spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA). In short, 20 uL of 10 ng/mL D8-Progesterone (internal standard) in ethanol was added to 250 uL of serum, followed by a liquid/liquid extraction using 1-chlorobutane. MPA was detected at a mass to charge transition 387.2 → 285.1 and D8-Progesterone at 323.3 → 100.1. Samples were quantified using a calibration line which was run on a daily basis together with quality controls. The assay is linear between 25 and 8000 pg/mL with a lower limit of quantification < 25 pg/mL. Inter-day precision was 9.1% at 118 pg/mL and 2.6% at 1021 pg/mL.

Enrollment of 132 women was planned a priori to have 80% power to detect a 30% or greater difference in continuation rates between the groups. With a two-sided α=0.05, β=0.80, and accounting for a predicted 20% dropout rate, enrolling 132 subjects in a 2:1 intervention to control ratio would suffice. We compared categorical and continuous variables using χ2, Fisher exact test, Student t test, or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. Spearman rank correlation was used to compare DMPA levels at 6 and 12 months. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical package v.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

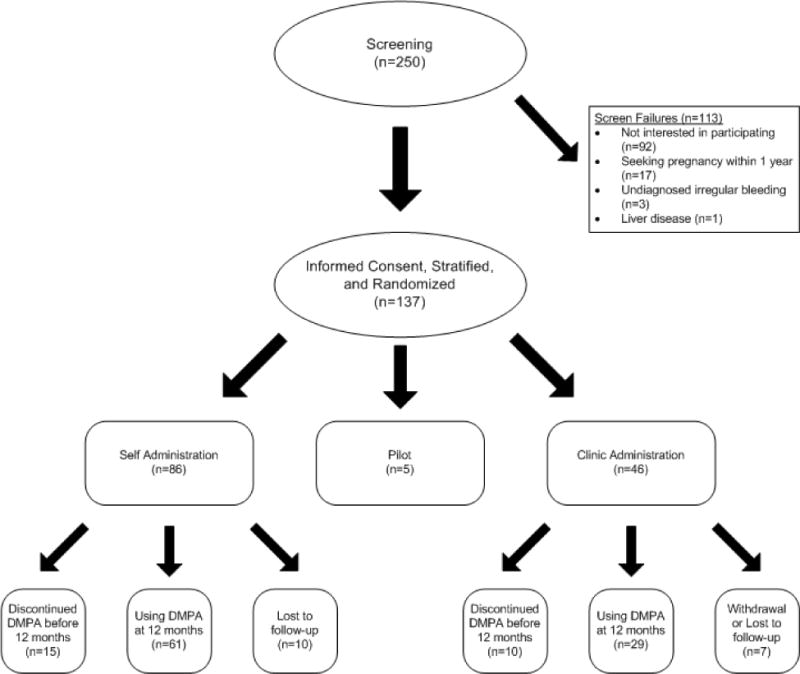

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through this trial. Two hundred fifty women were screened, and 63% were interested in study participation. One hundred thirteen (45%) did not meet eligibility criteria. We randomly assigned 132 participants – 86 to the self-administration group and 46 to the clinic administration group. Women in both groups had similar demographic characteristics, including mean age, marital status, education, number of dependents, financial status, access to a healthcare provider, and relationship status. Both groups had limited previous experience with self-injection or injection of others (Table 1).

Fig 1.

Flowchart of participants

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomization Group

| Self Administration (n=86) |

Clinic Administration (n=46) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | 26.0 ± 6.1 | 26.1 ± 6.3 | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.78 | ||

| Hispanic | 77 (90) | 41 (89) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5 (6) | 4 (9) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | |

|

| |||

| Education | 0.51 | ||

| Less than high school graduate | 27 (31) | 17 (37) | |

| High school graduate or greater | 59 (69) | 29 (63) | |

|

| |||

| Working outside the home | 41 (48) | 16 (35) | 0.15 |

|

| |||

| Current Student | 24 (28) | 9 (20) | 0.29 |

|

| |||

| Household size | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 3.85 ± 1.5 | 0.68 |

|

| |||

| Dependents | 1.20 ± 1.2 | 1.17 ± 1.3 | 0.91 |

|

| |||

| Working Medicaid | 38 (44) | 21 (46) | 0.87 |

|

| |||

| Ever had Medicaid | 68 (79) | 40 (87) | 0.26 |

|

| |||

| Current Smoker | 7 (8) | 6 (13) | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| Access to Regular Healthcare Provider | 25 (29) | 17 (40) | 0.35 |

|

| |||

| Ease of Access to Clinic | 0.72 | ||

| Very Easy | 33 (38) | 14 (30) | |

| Somewhat easy | 32 (37) | 21 (46) | |

| Somewhat hard | 17 (20) | 8 (17) | |

| Very hard | 4 (5) | 3 (6) | |

|

| |||

| Previously given self or other an injection | 15 (17) | 11 (24) | 0.24 |

|

| |||

| Tattoo | 28 (33) | 20 (43) | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Body Piercing | 23 (27) | 12 (26) | 0.72 |

|

| |||

| Scared of needles | 27 (31) | 15 (33) | 0.76 |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | 0.65 | ||

| Single | 61 (71) | 37 (80) | |

| Married | 15 (17) | 7 (15) | |

| Divorced | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| Separated | 6 (7) | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

|

| |||

| Current Partner | 71 (83) | 42 (91) | 0.17 |

|

| |||

| Gravidity | 1.93 ± 1.64 | 2.04 ± 1.7 | 0.71 |

Data are n(%) or mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified

One hundred fifteen women (87%) completed follow-up. Ten participants (11.6%) in the self-administration group and six (13.0%) in the clinic administration were lost to follow-up. In the following analyses we assumed that all participants who were lost to follow-up had discontinued DMPA use. One participant (2.1%) in the clinic administration group withdrew due to a desire to get pregnant. Seventy-one percent of the women in the self-administration group and 63% in the clinic administration group were using DMPA as their contraceptive method at study end (p = 0.47). Several women in both groups reported interruptions in use: only 47% and 49% of the self and clinic administration groups reported continuous uninterrupted use at one year (p = 0.70), respectively. The time between injections was similar in both groups; the median number of days between the forth and fifth injection was 84 days in the (CI: 84 – 89) self-administration group and 84 days (CI: 70 – 90) in the clinic administration group (p=0.38). There were no differences in continuation based on previous history of DMPA use.

Eighteen women using SC DMPA as their contraceptive method at study end had not used the method continuously, and they were successful in restarting DMPA outside of the clinical setting. Some crossover from SC to IM DMPA was observed; seven participants – three from the self-administration and four from the clinic administration group – were receiving IM DMPA in the clinical setting by study end. Two women in the self-administration group expressed dislike or discomfort with self-injection. Women who were not using DMPA at study end tended to switch to a less effective method: in the self-administration group, five women were not using a method either because they were seeking pregnancy or did not feel that they were at risk, five switched to oral contraceptives and three to condoms. In the clinic administration group, five also completely discontinued contraception use, two switched to oral contraceptives and one to condoms. Two participants in each group changed to IUD use.

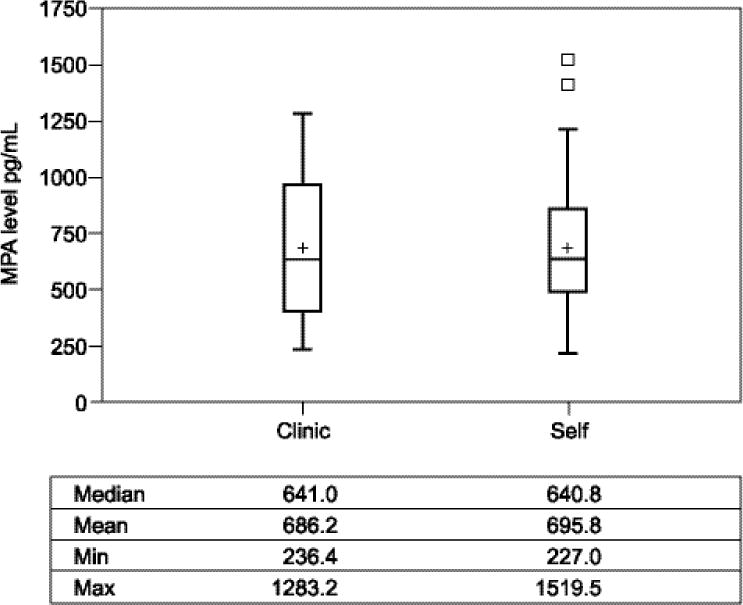

In this study, we were able to verify DMPA use in the self-administration group by measuring trough MPA levels. The average MPA level (figure 2) for uninterrupted continuers of SC DMPA immediately prior to the fifth scheduled contraceptive injection was 686.2 ± 318.5 pg/ml and 695.8 ± 309.6 pg/ml for the self-administration and clinic administration groups, respectively (p = 0.85); six month DMPA levels were similar. The correlation between the six and twelve month levels was 0.25 (p=0.02). All participants had MPA levels in the therapeutic range, both at six and twelve months [13, 14].

Figure 2.

Comparison of MPA Levels in SC Continuers at 12 Months

DISCUSSION

Multiple studies, including this one, have repeatedly shown that women are interested in the administration of injectable contraceptives in non-clinical settings [5–8, 15–17]. Even though SC DMPA has been available since Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in late 2004, it has been treated differently than other subcutaneous medications (e.g., insulin, gonadotropins, and heparin) which are routinely self-administered outside of the office, as it needs only to be injected quarterly to maintain clinical effectiveness. Consequently, we might thus be concerned whether patients are able to retain the skills necessary to inject SC DMPA appropriately and effectively when it is given on such an infrequent basis.

To our knowledge, this study is the largest, and only randomized, trial to date, examining self-administration of SC DMPA and adds support to the growing body of literature demonstrating that women are able to competently self-administer SC DMPA [6–8]. Furthermore, most injections were given within the prescribed dosing interval, and when not, women were able to self-restart via the Quickstart method [10].

Our findings, along with others, suggest a brief educational session using information contained in the package insert is sufficient for successful teaching and utilization [6, 8]. In contrast to other published studies, all of which relied on participant self-report, we were able to corroborate continued medication use with serum MPA levels and found that self-administration at home resulted in the same therapeutic levels as clinic administration by a health professional. While there may be wide variation in circulating MPA levels at the end of an injection period [18], it is well established that ovulation does not occur until serum levels are less than 0.1 ng/mL [13]. All women in this study who reported continuous use had MPA levels in the contraceptive range.

Continuation rates in this study were similar in the self- and clinic administration groups. These results do not support higher continuation rates in our study population as hypothesized, however, self-administration does offer other benefits such as less time spent on contracepting behaviors which translate to less time and cost for travel, time off from work, and healthcare costs associated with a provider visit.

Globally, self-administration of SC DMPA has the potential to revolutionize contraceptive uptake in developing areas. As it stands, many women already prefer injectable contraceptives to other modern methods because of their effectiveness, long-acting effects, discreet administration, and reversibility, and estimates suggest global use of injectables will increase to almost 40 million users over the next couple of years [19]. While multiple developing countries employ community-based lay healthcare workers trained to administer IM DMPA to women outside of clinic catchment areas, self-administration could have an even greater impact on number of women with access to DMPA.

This study included only women who were interested in DMPA use. A cross-sectional survey of adult women attending a family planning clinic found that among the 275 DMPA nonusers, 11% did not choose DMPA because of the required office visits, but 26% would seriously consider DMPA if they could self-administer at home. Forty percent of past users stated they would be interested in resuming DMPA if they could self-administer at home [16]. With over half of the women approached desiring participation, this study confirms that self-administration of DMPA may be an attractive option for many women. In addition, as nearly all women were able to administer SC DMPA without complication, self-administration is a feasible option.

IMPLICATIONS.

Self-administration of SC DMPA is a feasible and attractive option for many women. Benefits include increased control over contraceptive measures and less time spent on contracepting behaviors. Globally, self-administration has the potential to revolutionize contraceptive uptake by increasing the number of women with access to DMPA.

Acknowledgments

This was funded through investigator initiated grants from the Fellowship in Family Planning and Pfizer. This publication was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1 TR000040, formerly the National Center for Research Resources, Grant Number UL1 RR024156. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: Carolyn Westhoff is a consultant to Merck, Agile, and Bayer. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01019369

References

- 1.Frost JJ, Darroch JE, Remez L. Improving contraceptive use in the United States. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2008. In Brief. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreau C, Cleland K, Trussell J. Contraceptive discontinuation attributed to method dissatisfaction in the United States. Contraception. 2007 Oct;76(4):267–72. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul C, Skegg DCG, Williams S. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation. Contraception. 1997;56(4):209–14. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(97)00140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polaneczky M, Liblanc M. Long-term depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) use in inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23(2):81–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahamondes L, Marchi NM, Nakagava HM, De Melo ML, Cristofoletti Mde L, Pellini E, et al. Self-administration with UniJect of the once-a-month injectable contraceptive Cyclofem. Contraception. 1997;56(5):301–4. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(97)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prabhakaran S, Sweet A. Self-administration of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception: feasibility and acceptability. Contraception. 2012;85(5):453–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron ST, Glasier A, Johnstone A. Pilot study of home self-administration of subcutaneous depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. Contraception. 2012;85(5):458–64. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RL, Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD. Self-administration of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate by adolescent women. Contraception. 2013;88(3):401–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. Geneva: WHO Press; 2004. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/mec/mec.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rickert VI, Tiezzi L, Lipshutz J, Leon J, Vaughan RD, Westhoff C. Depo Now: preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(1):22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfizer. depo-subQ provera 104(r) medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable suspension 104 mg/0.65 mL: Physician Information. New York: Pharmacia and Upjohn Company; 2009. Available from: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=549. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estes CM, Ramierez J, Tiezzi L, Westhoff C. Self pregnancy testing in an urban family planning clinic: promising results for a new approach to contraceptive follow-up. Contraception. 2008;77(1):40–3. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz A, Hiroi M, Stanczyk FZ, Goebelsmann U, Mishell DR. Serum Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (MPA) Concentrations and Ovarian Function Following Intramuscular Injection of Depo-MPA. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1977;44(1):32–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem-44-1-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishell DR. Pharmacokinetics of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Journal of reproductive medicine. 1996;41(5 suppl):381–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picardo C, Ferreri S. Pharmacist-administered subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Contraception. 2010;82(2):160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lakha F, Henderson C, Glasier A. The acceptability of self-administration of subcutaneous Depo-Provera. Contraception. 2005 Jul;72(1):14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanwood NL, Eastwood K, Carletta A. Self-injection of monthly combined hormonal contraceptive. Contraception. 2006;73(1):53–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koetsawang S, Shrimanker K, Fotherby K. Blood levels of medroxyprogesterone acetate after multiple injections of DepoProvera or CycloProvera. Contraception. 1979;20(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(79)90038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keith B. Home-based Administration of depo-subQ provera 104(tm) in the Uniject(tm) Injection System: A literature Review. Seattle: PATH; 2011. [Google Scholar]