Abstract

Purpose

To report quality of life (QOL)/toxicity in men treated with proton beam therapy (PBT) for localized prostate cancer and to compare outcomes between passively scattered proton therapy (PSPT) and spot-scanning proton therapy (SSPT).

Methods and Materials

Men with localized prostate cancer enrolled on a prospective QOL protocol with a minimum of 2 years follow-up were reviewed. Comparative groups were defined by technique (PSPT vs. SSPT). Patients completed Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) questionnaires at baseline and every 3-6 months after PBT. Clinically meaningful differences in QOL were defined as ≥0.5 × baseline standard deviation. The cumulative incidence of modified RTOG grade ≥2 GI or GU toxicity and argon plasma coagulation (APC) were determined by the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

226 men received PSPT and 65 SSPT. Both PSPT and SSPT resulted in statistically significant changes in sexual, urinary, and bowel EPIC summary scores. Only bowel summary, function, and bother resulted in clinically meaningful decrements beyond treatment completion. The decrement in bowel QOL persisted through 24-month follow-up. Cumulative grade ≥2 GU and GI toxicity at 24 months were 13.4% and 9.6%, respectively. There was one Grade 3 GI toxicity (PSPT group) and no other grade 3 or greater GI or GU toxicity. APC application was infrequent (PSPT 4.4% vs. SSPT 1.5%; p = 0.21). No statistically significant differences were appreciated between PSPT and SSPT regarding toxicity or QOL.

Conclusion

Both PSPT and SSPT confer low rates of grade ≥ 2 GI or GU toxicity with preservation of meaningful sexual and urinary QOL at 24 months. A modest, yet clinically meaningful, decrement in bowel QOL was seen throughout follow-up. No toxicity or QOL differences between PSPT and SSPT were identified. Long term comparative results in a larger patient cohort are warranted.

Introduction

Due to unique dose deposition characteristics, proton beam therapy (PBT) was one of the original methods for prostate cancer dose-escalation. Subsequently, multiple prospective series established the safety and efficacy of this technology in men with localized prostate cancer.(1–8)

There currently exist two predominant systems of PBT delivery: passively scattered proton therapy (PSPT) and spot scanning proton therapy (SSPT). In prostate cancer, recent comparative dose modeling studies demonstrated superior dose distribution to non-target tissue in the low, medium, and high dose ranges with SSPT compared with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and PSPT.(9–13) Although the collective experience treating localized prostate cancer with PBT extends back several decades, the published literature to date consists uniformly of men treated with PSPT. Within the next several years, multiple proton centers are slated to open with SSPT capability. The purpose of the current study is to report and compare early quality of life (QOL) and treatment toxicity in men treated with PSPT and the newer SSPT for localized prostate cancer.

Methods and materials

Patients

Patients were enrolled on an institutional review board approved, prospective quality of life trial at a single tertiary cancer center from 2006 through 2012. All patients provided written informed consent for participation. Men with previously untreated, nonmetastatic prostate cancer were eligible. The study group for this analysis consists of registered patients with a minimum of 2-years follow-up.

Data Collection and Follow-Up

The Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite questionnaire (EPIC-50) was administered prior to any treatment, at the conclusion of PBT, and at each follow-up evaluation. Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicity was recorded using modified Radiation Therapy Oncology Group toxicity criteria (see supplementary tables). Events that occurred between follow-up visits were also captured.

Treatment planning technique

All patients underwent computed tomography simulation. Ultrasound bladder volume quantification, conventional leg and thigh immobilization, and a gas-release endo-rectal balloon were used for all simulations and proton treatments. Kilovoltage xray positioning verification was used daily. The method of PBT delivery (PSPT vs. SSPT) was at the discretion of the treating physician.

Both PSPT and SSPT consisted of opposed right and left lateral beam arrangements with incident proton beam energies typically from 150–225 MeV. Both fields were treated daily. The clinical target volume (CTV) was generally customized according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) risk stratification as follows: low risk (prostate only), intermediate-risk (prostate + proximal seminal vesicle), and high risk (prostate + full seminal vesicle). For PSPT, an evaluation target volume (ETV) was applied as a 6 millimeter (mm) radial expansion of the CTV except posteriorly; where the margin was limited to 5 mm. Proximal and distal margins were typically 9-12 mm based on the formula popularized by Moyers et al.(14) For SSPT, a scanning target volume (STV) margin was applied as follows: 12 mm laterally, 6 mm in all other dimensions except 5 mm posteriorly to the CTV. The total prescribed dose was 76 Gy (RBE), delivered in 38 equivalent fractions. The relative biological effectiveness correction factor for physical to biological dose was 1.1. Treatment was designed to cover 100% of the CTV and >95% of the STV/ETV. The intended total dose was prescribed to an isodose line above 95% for optimal homogeneity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristic differences were assessed with Fisher's exact test and nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. QOL was evaluated primarily as the change over time from baseline stratified within each treatment group and across EPIC-50 domains of sexual function/bother, urinary incontinence, urinary obstruction/irritation, urinary function/bother, and bowel function/bother. Scores for patient-reported outcomes, as measured by EPIC-50, were calculated according to the instrument instructions.(15) Resulting domain scores range from 0 to 100, with higher values representing more favorable QOL.

To assess which QOL domains were affected over time by proton delivery system, we evaluated the time profiles of EPIC-50 scores to assess whether the mean score changes from baseline at each follow-up time point was different using a one-sample t-test. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value <0.05. A clinically meaningful change in quality of life was defined as a change from baseline to follow-up assessment that exceeded one-half the standard deviation of the baseline value.(16) Mixed-effects repeated measures regression modeling of demographic and clinical variables was used to identify associations with EPIC-50 domain and sub-domain scores over time. A log-rank test was used to compare incidence of GI and GU toxicity, including the cumulative incidence of argon plasma coagulation (APC) application for rectal bleeding. Analyses were performed with the use of SAS 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Patients

Table 1 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. Two-hundred ninety one patients were eligible for this analysis (226 treated with PSPT and 65 treated with SSPT).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| PSPT (n =226) | SSPT (n = 65) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis in years (range) | 63 (47-82) | 66 (50-83) | 0.01 | |

| Race (no. %) | 0.04 | |||

| White | 205 (91) | 58 (89) | ||

| Black | 9 (4) | 2 (3) | ||

| Hispanic | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Asian | 3 (1) | 3 (5) | ||

| Other | 1 (<1) | 2 (3) | ||

| NCCN Risk Group (no. %) | 0.05 | |||

| Low | 88 (39) | 32 (49) | ||

| Intermediate | 138 (61) | 32 (49) | ||

| High | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | ||

| Median PSA in ng/ml (Range) | 4.5 (0.1-18.6) | 4.8 (0.3-19.2) | 0.18 | |

| T-stage (no. %) | 0.85 | |||

| T1b | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | ||

| T1c | 167 (74) | 52 (80) | ||

| T2a | 40 (18) | 10 (15) | ||

| T2b | 17 (8) | 3 (5) | ||

| T2c | 2 (<1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Gleason score (no. %) | 0.03 | |||

| 6 | 90 (40) | 34 (52) | ||

| 7 | 136 (60) | 30 (46) | ||

| 8 | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | ||

| Hormone Therapy (no. %) | <0.001 | |||

| No | 130 (58) | 54 (83) | ||

| Yes | 96 (42) | 11 (17) | ||

| Anti-coagulant medications (no. %) | 0.32 | |||

| No | 129 (57) | 32 (49) | ||

| Yes | 97 (43) | 33 (51) | ||

| Hemorrhoids | 0.99 | |||

| No | 139 (62) | 40 (63) | ||

| Yes | 87 (39) | 25 (37) | ||

| Median Serum Testosterone in ng/dl (Range) | 358 (6-893) | 326 (50-650) | 0.29 | |

Abbreviations: no. = number, NCCN = national comprehensive cancer network, PSA = prostate specific antigen, PSPT = passive scattering proton therapy, SSPT = spot scanning proton therapy

Quality of Life

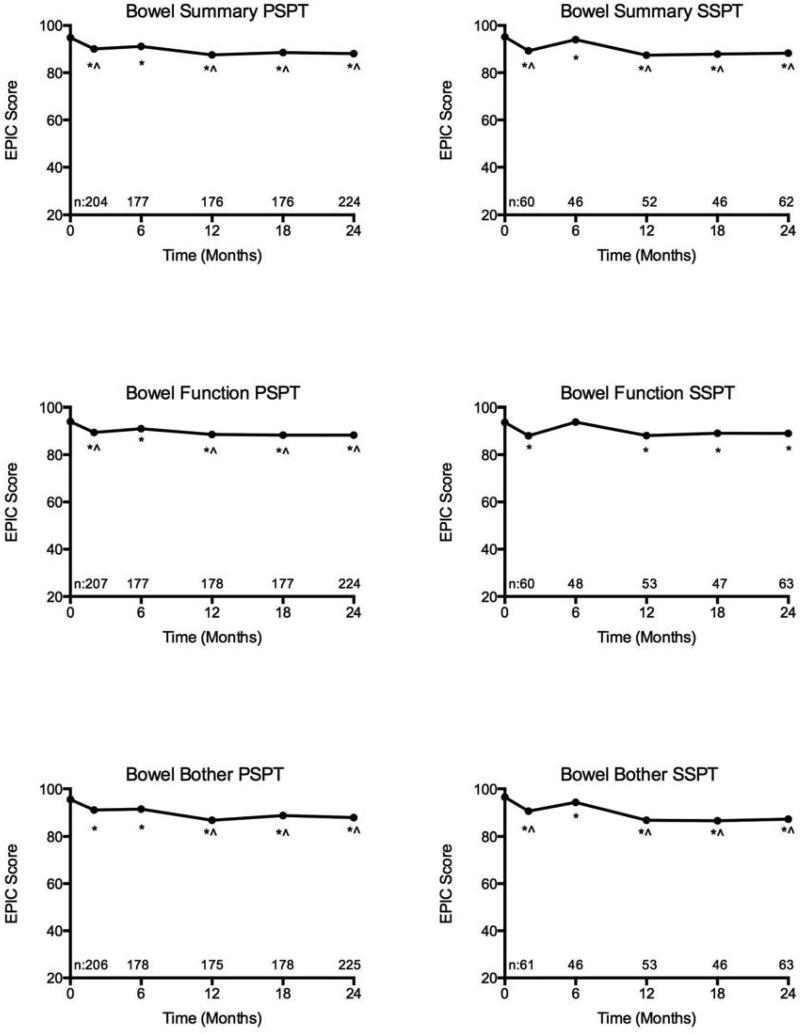

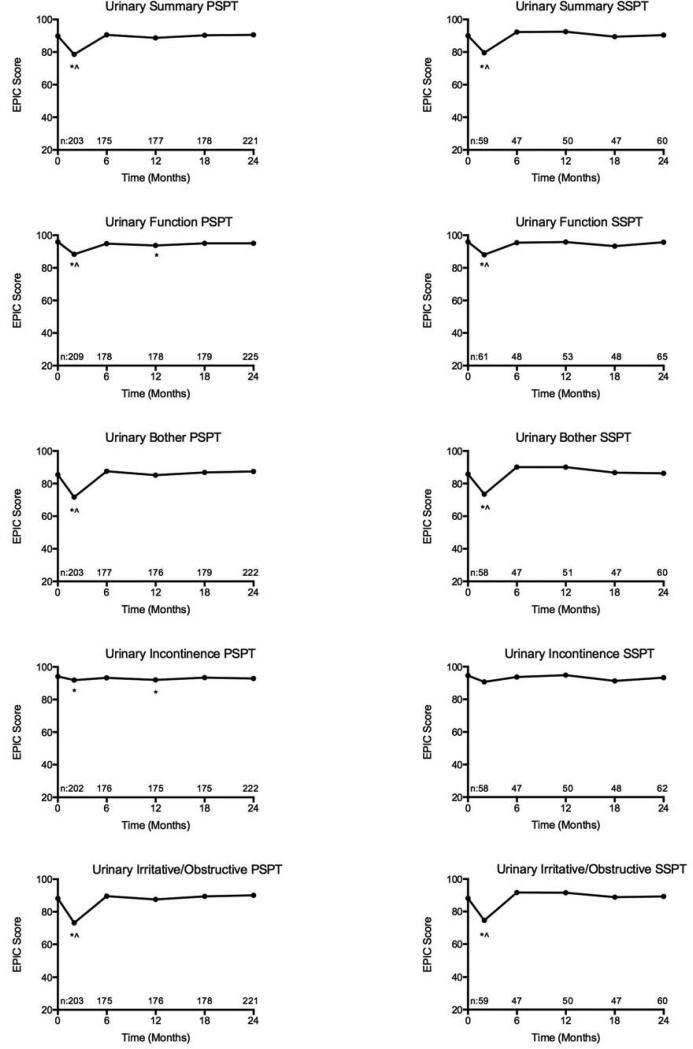

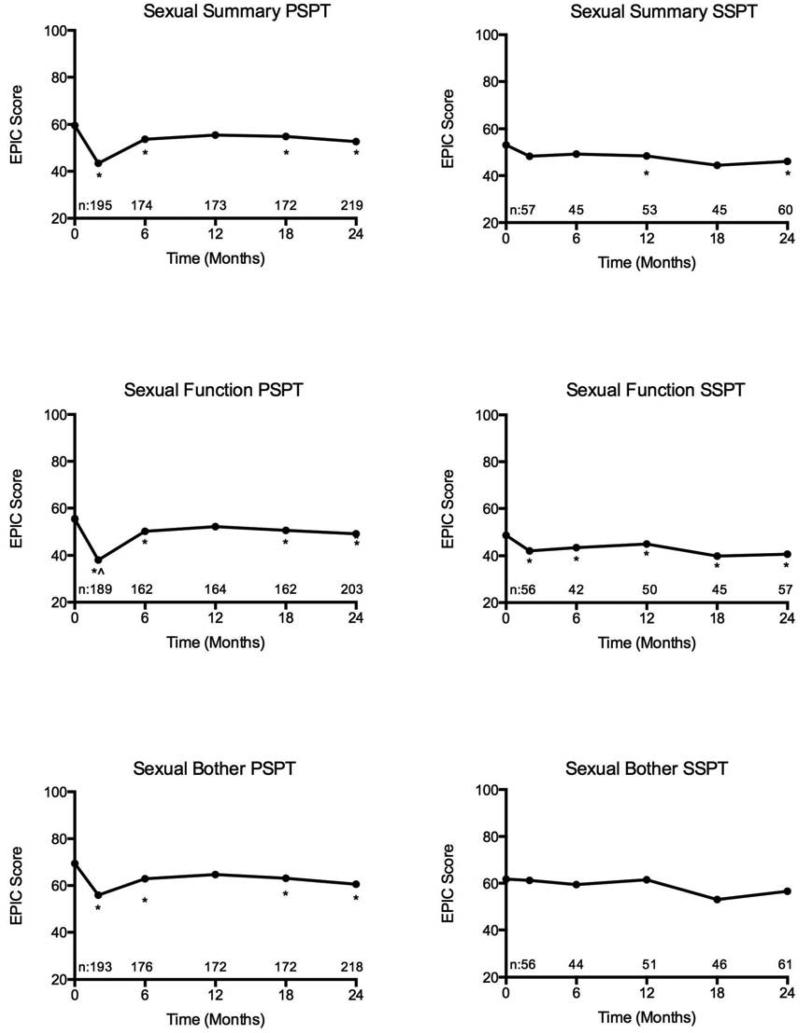

Mean EPIC-50 scores over time across bowel, sexual, and urinary domains for patients treated with PSPT and SSPT are illustrated in Figures 1-3.

Figure 1.

Bowel domain quality of life after passively scattered (PSPT) and spot-scanning proton therapy (SSPT) for localized prostate cancer (*statistically significant and ^clinically meaningful decline from baseline).

Figure 3.

Urinary domain and subdomain quality of life after passively scattered (PSPT) and spot-scanning proton therapy (SSPT) for localized prostate cancer (*statistically significant and ^clinically meaningful decline from baseline).

Bowel Domain

There were statistically significant changes in bowel quality of life in both the PSPT and SSPT groups. Statistically significant changes from baseline in bowel function and bother persisted through two-years of follow-up for both groups. The mean change from baseline in bowel function for men treated with PSPT and SSPT at 2-years were −5.5 (p<0.001) and −4.6 (p<0.001) respectively. The mean change from baseline in bowel bother for men treated with PSPT and SSPT at 2-years were −7.7 (p<0.001) and −9.4 (p<0.001). In the PSPT group, clinically meaningful changes from baseline in both bowel function and bother were appreciated after 6-months. In the SSPT group, clinically meaningful decrements from baseline bowel bother were found at all follow-up time points, with the exception of 6-months. There were no clinically meaningful changes in bowel function in men treated with SSPT. The overall magnitude of bowel function and bother decrement was relatively small at each time-point (mean bowel function change −4.38; range −0.3 to −5.6; mean bowel bother change −7.17; range −3.3 to −10.9). In comparison between PSPT and SSPT, there were no statistically significant differences in bowel function or bother.

Sexual Domain

There were statistically significant changes from baseline in sexual function for both the PSPT and SSPT groups. Statistically significant changes from baseline in sexual function persisted through two years of follow-up for both groups. The mean change from baseline in sexual function for the PSPT and SSPT groups at 24-months were −5.8 (p = 0.002) and −11.9 (p < 0.001) respectively. For patients treated with PSPT, clinically significant differences in sexual function were present at treatment completion (mean change −17.7; p = 0.012) with resolution at 6-month follow-up (mean change −5.1, p = 0.999). There were no clinically meaningful changes in sexual function at any time point in the SSPT group. There were statistically significant changes in sexual bother in the PSPT group, but not the SSPT group. The mean change in sexual bother in the PSPT and SSPT groups at 24 months were −8.5 (p = 0.001) and –7.4 (p = 0.084) respectively. There were no clinically meaningful changes in sexual bother from baseline in either group. In comparison between PSPT and SSPT, there were no significant differences in sexual function or bother. In consideration of baseline differences between the treatment groups, mixed variable regression analysis was performed inclusive of demographic, clinical, and treatment features. Only receipt of ADT and older age predicted for worse sexual domain QOL.

Urinary Domain

There were statistically significant changes from baseline in urinary function at the end of treatment for both the PSPT (−7.8; p<0.001) and SSPT (−7.8; p<0.001) groups and also at 12-months for the PSPT group (−1.9; p = 0.009). No statistically significant changes from baseline in urinary function were appreciated in either group after 12-months. The mean change from baseline in urinary function at 24-months in the PSPT and SSPT were −0.9 (p = 0.112) and −0.3 (p = 0.783) respectively. In both the PSPT and SSPT groups, clinically meaningful decrements in urinary function, bother, and irritation/obstruction were appreciable at the end of treatment. However, no clinically meaningful differences were appreciated in either group compared to baseline after treatment completion.

There were statistically significant changes from baseline in urinary bother at the end of treatment for both the PSPT (−14; p<0.001) and SSPT (−12; p<0.001) groups. No statistically significant worsening from baseline in urinary bother was appreciated in either group after treatment completion with mean bother scores actually reflecting less bother after therapy in both groups. The mean change from baseline in urinary bother at 24-months in the PSPT and SSPT were +2.2 (p = 0.016) and +0.2 (p = 0.898) respectively.

With respect to specific urinary complaints measured by EPIC-50, there were no statistically significant or clinically meaningful changes in urinary incontinence compared to baseline in the SSPT group. However, in the PSPT group, a statistically significant, but not clinically meaningful, change was appreciated at treatment conclusion (−2.7; p = 0.003) and 12-months (−1.8; p = 0.046). The mean change from baseline in urinary incontinence at 24-months in the PSPT and SSPT groups were −1.3 (p = 0.118) and −1.7 (p = 0.377) respectively. There were statistically significant changes in urinary irritation or obstruction in both the PSPT (−15.3; p<0.001) and SSPT (−13.1; p <0.001) groups at the end of treatment compared to baseline. Urinary irritation and obstruction resolved in both groups by 6-months with mean urinary irritation or obstruction scores actually reflecting less irritation or obstruction than baseline following treatment completion. The mean change from baseline in urinary irritation or obstruction at 24-months in the PSPT and SSPT were +2.0 (p = 0.006) and +0.9 (p = 0.575), respectively. No significant differences were seen in urinary function, bother, incontinence, or obstruction/irritation between PSPT and SSPT.

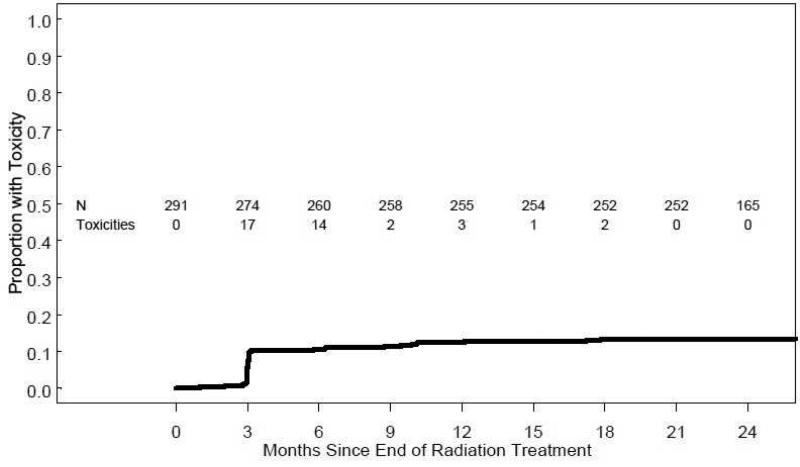

Toxicity

The cumulative incidence of grade 2 or higher GU toxicity is illustrated in Figure 4. For all patients, the cumulative incidence of grade 2 or greater GU toxicity by 24 months from treatment completion was 13.4% (95% CI 9.4%-17.2%). No patient had grade 3 or higher GU toxicity. Nearly all GU toxicity occurred within the first 12 months of treatment. There were no significant differences in the 24 month cumulative incidence of grade 2 or greater GU toxicity for patients treated with PSPT (14.2%) versus SSPT 10.8% (p = 0.449).

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of modified RTOG grade ≥2 GU toxicity

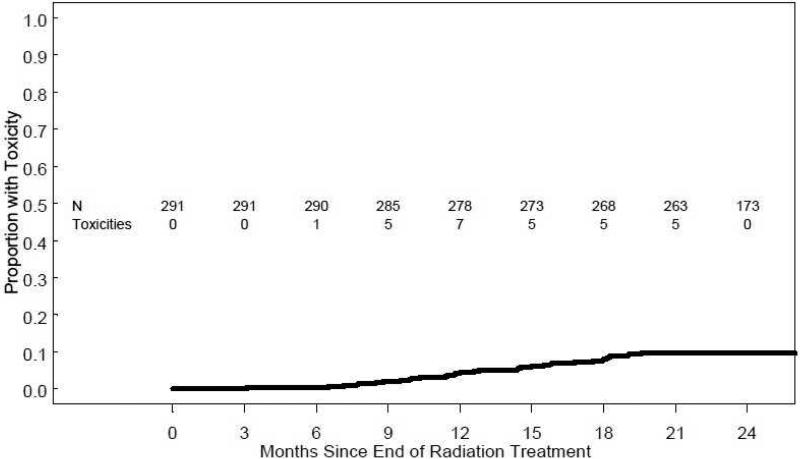

The cumulative incidence of grade 2 or higher GI toxicity is illustrated in Figure 5. For all patients, the cumulative incidence of grade 2 or greater GI toxicity by 24 months from treatment completion was 9.6% (95% CI 6.2%-12.9%). There was one patient with grade 3 GI toxicity (PSPT group). There was no grade 4 or higher GI toxicity. All GI toxicity occurred at a minimum of 6-months after treatment. There were no significant differences in the 24 month cumulative incidence of grade 2 or greater GI toxicity for patients treated with PSPT (10.2%) versus SSPT 7.7% (p = 0.560).

Figure 5.

Cumulative incidence of modified RTOG grade ≥2 GI toxicity

For all patients, the cumulative incidence of APC by 24 months from treatment completion was 3.8% (95% CI 1.6%-5.9%). Men treated with PSPT received APC for rectal bleeding more often than men treated with SSPT, however, this difference failed to reach statistical significance (PSPT 4.4% vs. SSPT 1.5%; p = 0.213).

Discussion

In this analysis of a prospectively assessed cohort of men with localized prostate cancer, PBT resulted in low cumulative incidence of grade ≥ 2 GI or GU toxicity with clinically modest effects on sexual, bowel, and urinary QOL. To our knowledge, this is the first report of toxicity and patient reported QOL in a cohort of men treated with SSPT for localized prostate cancer. The current study failed to demonstrate a difference in toxicity or QOL between PSPT and SSPT.

QOL

Our findings using EPIC-50 are consistent with and additive to previously published patient reported QOL outcome studies after high dose PBT for prostate cancer. A recent publication by Gray et al.(17) reviewed patient reported QOL following 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT), IMRT, or PBT. The Prostate Cancer Symptom Indices (PCSI) scale, an instrument similar to the EPIC-50, was used for domain specific QOL assessment of men treated with PBT.(18) Score adjustments were performed in order to scale the PCSI from 0-100. A clinically meaningful decrement in bowel QOL was appreciated at 12 and 24 months across all modalities. The mean bowel score change from baseline at 12 and 24 months for men treated with PBT was −6.4 and −3.7 respectively. Interestingly, men who were treated with 3DCRT and IMRT reported a clinically meaningful decrement in bowel QOL at initial follow-up (~3-months), while men treated with PBT did not. The hypotheses that PBT might improve bowel QOL compared to IMRT is currently being tested in a multi-institutional randomized trial (NCT01617161). In the same study by Gray et al., men treated with PBT experienced a clinically meaningful decrement in urinary irritation/obstruction 12-months following treatment completion (mean change from baseline – 6), however, the urinary QOL differences had resolved by 24-months (mean change from baseline −2.3). Although direct comparisons between different QOL instruments should be made cautiously, our results are consistent with those reported by Gray et al. including the finding of modest bowel QOL impact within the first several months following treatment.

The University of Florida recently reported QOL outcomes using the EPIC questionnaire in 262 men ≤ 60 years old treated with definitive PSPT with median 24 month follow-up.(19) The change in urinary, bowel, and sexual summary score from baseline at 24-months were −3.1, −4.8, and −12.6 respectively. Using the conventional definition of 0.5 multiplied by the baseline standard definition, only bowel QOL decrement was clinically meaningful. Our findings support those of Hoppe et al. as we did not appreciate clinically meaningful differences from baseline in urinary or sexual function or bother at 24-months following treatment, but we did detect clinically meaningful decrements in bowel function and bother after 6-month follow-up in men treated with either PSPT or SSPT.

Toxicity

We report a cumulative incidence of 13.4% grade ≥ 2 GU and 9.6% grade ≥ 2 GI toxicity with limited grade 3 or greater GI/GU toxicity. Our findings are consistent with other contemporary North American series.

The University of Florida presented their early results of 212 patients treated according to one of three prospective trials with all patients having a minimum follow-up of two years.(8). Treatments were prescribed as follows: 78 Gy (RBE) (low-risk), 78-82 Gy (RBE) (intermediate risk), and 78 Gy (RBE) with concomitant taxotere followed by androgen deprivation (high risk). The incidence of grade ≥ 3 GU toxicity was 1.9% and the incidence of grade ≥3 GI toxicity was <0.5%. The rates of grade ≥ 2 GU and GI toxicity were 24% and 4% respectively. Our series compares favorably to prior series and is the first series to include patients treated with SSPT.

A particularly interesting finding in our comparison between PSPT and SSPT is the relative cumulative incidence of APC favoring SSPT. The volume of rectum receiving 70 Gy or more (rectal V70) is a validated predictor of bowel toxicity.(20–22) SSPT allows significant improvement in the dose given to the rectum compared to PSPT without compromising target coverage.(13) The achievable mean rectal V70 was lower using SSPT compared to PSPT (7.5% vs. 13.3%; p <0.01). Moreover, the improved dosimetic profile of SSPT was consistent across low, intermediate, and high dose levels. In consideration of these differences, one might expect to appreciate differences in bowel QOL, GI toxicity, and incidence of APC between PSPT and SSPT. Although bowel function, grade ≥ 2 GI toxicity, and cumulative incidence of APC favored SSPT, these differences were not statistically significant. The relatively small patient numbers, low incidence of toxic events, and modest absolute decline in bowel QOL regardless of PBT technique likely compromised our ability to identify potential differences between PSPT and SSPT. The relatively favorably bowel profile and lower cumulative incidence of APC in men treated with SSPT is consistent with expectations derived from dose modeling studies and thus requires further evaluation in a larger patient cohort.

The current analysis has several limitations: 1) considering this report is a preliminary subset analysis of a prospective trial, comparative assessments between PSPT and SSPT were not specifically considered in the statistical design. Consequently, our power toward detecting differences in QOL or toxicity between PBT techniques is likely limited. In addition, baseline differences between men treated with PSPT and SSPT, has the potential to skew interpretation of comparative QOL and/or toxicity results. It is the authors’ impression that these imbalances have little to no impact on the conclusions offered here. 2) Men treated with SSPT in this analysis were some of the first patients treated with this technique at our institution and in North America. One might expect a “learning curve” effect with application of a new modality. We do not believe either of these limitations hinders interpretation of the data presented. Furthermore, long-term follow-up in this patient cohort should counter-balance these limitations.

Conclusions

PBT for localized prostate cancer conferred low rates of grade ≥ 2 GI or GU toxicity without clinically meaningful changes from baseline sexual or urinary QOL after treatment completion. A modest, but clinically meaningful decrement in bowel QOL was appreciated throughout 24-month follow-up. Although no significant differences in toxicity or QOL were appreciated in comparison between SSPT and PSPT, the overall profile including the cumulative incidence of APC favored SSPT. Future comparative analyses between SSPT and PSPT are warranted in a larger cohort.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY.

This study compares toxicity and quality of life associated with spot-scanning proton therapy (SSPT) versus conventional passively scattered proton therapy (PSPT) in men with localized prostate cancer and reports preliminary QOL and toxicity data from a prospective trial. Higher grade toxicity was infrequent. QOL was generally preserved. A modest, yet clinically meaningful, decrement in bowel QOL was seen throughout follow-up using either technique. No toxicity or QOL differences between PSPT and SSPT were identified.

Figure 2.

Sexual domain quality of life after passively scattered (PSPT) and spot-scanning proton therapy (SSPT) for localized prostate cancer (*statistically significant and ^clinically meaningful decline from baseline).

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant (CA016672).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest Notification: No actual or potential conflicts of interests have been identified by the authors of this original work.

References

- 1.Yonemoto LT, Slater JD, Rossi CJ, Jr, Antoine JE, Loredo L, Archambeau JO, et al. Combined proton and photon conformal radiation therapy for locally advanced carcinoma of the prostate: preliminary results of a phase I/II study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1997 Jan 1;37(1):21–9. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JD, Rossi CJ, Jr, Miller DW, Adams JA, et al. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 Sep 14;294(10):1233–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talcott JA, Rossi C, Shipley WU, Clark JA, Slater JD, Niemierko A, et al. Patient-reported long-term outcomes after conventional and high-dose combined proton and photon radiation for early prostate cancer. JAMA. 2010 Mar 17;303(11):1046–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nihei K, Ogino T, Onozawa M, Murayama S, Fuji H, Murakami M, et al. Multi-Institutional Phase II Study of Proton Beam Therapy for Organ-Confined Prostate Cancer Focusing on the Incidence of Late Rectal Toxicities. [2011 Jul 19];Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys [Internet] 2010 Sep 8; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.027. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20832180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Nihei K, Ogino T, Ishikura S, Kawashima M, Nishimura H, Arahira S, et al. Phase II feasibility study of high-dose radiotherapy for prostate cancer using proton boost therapy: first clinical trial of proton beam therapy for prostate cancer in Japan. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005 Dec;35(12):745–52. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shipley WU, Tepper JE, Prout GR, Jr, Verhey LJ, Mendiondo OA, Goitein M, et al. Proton radiation as boost therapy for localized prostatic carcinoma. JAMA. 1979 May 4;241(18):1912–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duttenhaver JR, Shipley WU, Perrone T, Verhey LJ, Goitein M, Munzenrider JE, et al. Protons or megavoltage X-rays as boost therapy for patients irradiated for localized prostatic carcinoma. An early phase I/II comparison. Cancer. 1983 May 1;51(9):1599–604. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830501)51:9<1599::aid-cncr2820510908>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendenhall NP, Li Z, Hoppe BS, Marcus RB, Mendenhall WM, Nichols RC, et al. Early Outcomes From Three Prospective Trials of Image-Guided Proton Therapy for Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2012 Jan;82(1):213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowdell SJ, Metcalfe PE, Morales JE, Jackson M, Rosenfeld AB. A comparison of proton therapy and IMRT treatment plans for prostate radiotherapy. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2008 Dec;31(4):325–31. doi: 10.1007/BF03178602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kase Y, Yamashita H, Fuji H, Yamamoto Y, Pu Y, Tsukishima C, et al. A Treatment Planning Comparison of Passive-Scattering and Intensity-Modulated Proton Therapy for Typical Tumor Sites. [2011 Dec 24];J. Radiat. Res. [Internet] 2011 Dec 1; doi: 10.1269/jrr.11136. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22129564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Widesott L, Pierelli A, Fiorino C, Lomax AJ, Amichetti M, Cozzarini C, et al. Helical tomotherapy vs. intensity-modulated proton therapy for whole pelvis irradiation in high-risk prostate cancer patients: dosimetric, normal tissue complication probability, and generalized equivalent uniform dose analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011 Aug 1;80(5):1589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz M, Pierelli A, Fiorino C, Fellin F, Cattaneo GM, Cozzarini C, et al. Helical tomotherapy and intensity modulated proton therapy in the treatment of early stage prostate cancer: a treatment planning comparison. Radiother Oncol. 2011 Jan;98(1):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi S, Amin M, Palmer M, Zhu XR, Nguyen Q, Pugh TJ, et al. Comparison of Intensity Modulated Proton Therapy (IMPT) to Passively Scattered Proton Therapy (PSPT) in the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2011 Oct;81:S154–S155. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moyers MF, Miller DW, Bush DA, Slater JD. Methodologies and tools for proton beam design for lung tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2001 Apr 1;49(5):1429–38. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000 Dec 20;56(6):899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008 Mar 20;358(12):1250–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray PJ, Paly JJ, Yeap BY, Sanda MG, Sandler HM, Michalski JM, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after 3-dimensional conformal, intensity-modulated, or proton beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013 May 1;119(9):1729–35. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coen JJ, Paly JJ, Niemierko A, Weyman E, Rodrigues A, Shipley WU, et al. Long-Term Quality of Life Outcome after Proton Beam Monotherapy for Localized Prostate Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys [Internet] 2011 May 26; doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.03.048. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21621343. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Hoppe BS, Nichols RC, Henderson RH, Morris CG, Williams CR, Costa J, et al. Erectile function, incontinence, and other quality of life outcomes following proton therapy for prostate cancer in men 60 years old and younger. Cancer. 2012 Sep 15;118(18):4619–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pederson AW, Fricano J, Correa D, Pelizzari CA, Liauw SL. Late toxicity after intensity-modulated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer: an exploration of dose-volume histogram parameters to limit genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicity. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012 Jan 1;82(1):235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen PL, Chen RC, Hoffman KE, Trofimov A, Efstathiou JA, Coen JJ, et al. Rectal dose-volume histogram parameters are associated with long-term patient-reported gastrointestinal quality of life after conventional and high-dose radiation for prostate cancer: a subgroup analysis of a randomized trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010 Nov 15;78(4):1081–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamstra DA, Conlon ASC, Daignault S, Dunn RL, Sandler HM, Hembroff AL, et al. Multi-institutional Prospective Evaluation of Bowel Quality of Life After Prostate External Beam Radiation Therapy Identifies Patient and Treatment Factors Associated With Patient-Reported Outcomes: The PROSTQA Experience. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013 Jul 1;86(3):546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.