Abstract

The PI3K-AKT pathway is hyperactivated in many human cancers, and several drugs to inhibit this pathway, including the PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor NVP-BEZ235, are currently being tested in various pre-clinical and clinical trials. It has been shown that pharmacological inhibition of the PI3K-AKT pathway results in feedback activation of other oncogenic signaling pathways, which likely will limit the clinical utilization of these inhibitors in cancer treatment. However, the underlying mechanisms of such feedback regulation remain incompletely understood. The PI3K-AKT pathway is a validated therapeutic target in renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Here we show that FoxO transcription factors serve to promote AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment in renal cancer cells. Inactivation of FoxO attenuated NVP-BEZ235-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, and rendered renal cancer cells more susceptible to NVP-BEZ235-mediated cell growth suppression in vitro and tumor shrinkage in vivo. Mechanistically, we showed that FoxOs upregulated the expression of Rictor, an essential component of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2), in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment, and revealed that Rictor is a key downstream target of FoxOs in NVP-BEZ235-mediated feedback regulation. Finally, we show that FoxOs similarly modulate the feedback response on AKT Ser473 phosphorylation and renal tumor growth by other PI3K or AKT inhibitor treatment. Together, our study reveals a novel mechanism of PI3K-AKT inhibition-mediated feedback regulation, and may identify FoxO as a novel biomarker to stratify RCC patients for PI3K or AKT inhibitor treatment, or a novel therapeutic target to synergize with PI3K-AKT inhibition in RCC treatment.

Keywords: FoxO, feedback regulation, PI3K, AKT, PI3K inhibitor

Introduction

The PI3K-AKT signaling pathway plays a key role in linking the extracellular growth factor stimulation to various cellular processes, including cell growth, proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis (1, 2). Activation of PI3K by growth factor binding to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) results in phosphorylation of plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to form PIP3. Subsequently, PIP3 recruits other downstream effector proteins to the plasma membrane, prominent among which is the serine/threonine kinase AKT. At the plasma membrane, AKT is further activated through phosphorylation of Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 2 (mTORC2). Once fully activated, AKT phosphorylates other target proteins, including the TSC1-TSC2 complex, and FoxOs (3). The TSC1-TSC2 complex inhibits mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), which functions to promote protein synthesis and cell growth. AKT-mediated phosphorylation of TSC2 inhibits the TSC1-TSC2 complex function, and thus activates mTORC1 signaling (4). FoxO transcription factors mainly function to promote cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via regulation of diverse arrays of transcription targets. AKT phosphorylation of FoxOs leads to FoxO sequestration in the cytoplasm and inactivates their transcription activities (5–8). Aberrant activation of this signaling network has been observed in virtually all human cancers (9–12). In particular relevance to this study, the recent data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project revealed that the PI3K-AKT pathway is altered in around 30% of RCCs (13).

RCC accounts for 3% of all malignancies in adults, and ranks among the top ten cancers in the United States (14, 15). Traditional chemotherapy, hormonal therapy or radiation is not effective in the treatment of advanced RCC. mTOR is a validated therapeutic target in RCC, as mTORC1 hyperactivation has been observed in most human RCC samples (16–18), and several clinical trials established the clinical benefit of mTORC1 inhibitors (19–21). However, the clinical response of RCC to mTOR inhibition has been modest, and most RCC patients receiving mTOR inhibitor treatment eventually developed resistance (19–21), which may be associated with mTORC1-mediated feedback regulation of the upstream PI3K-AKT pathway. A number of studies have shown that, while activated PI3K-AKT signaling promotes mTORC1 activation, mTORC1 hyperactivation also leads to feedback shutoff of the PI3K-AKT signaling (22–27). These observations suggest that mTOR inhibitor treatment alone, while inhibiting mTORC1-mediated protein synthesis and cell growth, also stimulates PI3K-AKT–dependent survival and cell cycle entry, which might explain the relatively moderate impact of mTOR inhibitor in treating RCC (28).

These observations prompted ideas for inhibiting the upstream PI3K-AKT pathway in the treatment of RCC as well as other cancers (29). Indeed, a recent study (30) showed that NVP-BEZ235, a PI3K and mTOR dual inhibitor (31), induced more potent growth arrest and apoptotic responses in RCC cells than did rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor. Currently, NVP-BEZ235, or other drugs to inhibit PI3K-AKT pathway, including BKM120 and MK-2206, are being tested in various RCC clinical trials. However, several studies conducted in the context of other cancers revealed that pharmacological inhibition of the PI3K-AKT pathway induced new compensatory activation of other oncogenic pathways, including FoxO-mediated upregulation of RTK expression, which might limit the clinical utilization of these inhibitors in cancer treatment (32–37). However, whether and how PI3K-AKT inhibition-mediated feedback regulation operates in RCC remains undefined.

In this study, utilizing mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and various renal cancer cells as model system, we investigated the underlying mechanisms of FoxO-mediated feedback regulation and the role of FoxOs in renal tumor development in response to PI3K-AKT inhibition. We identify a novel feedback mechanism that FoxOs promote PI3K-AKT inhibition-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation likely via transcriptional upregulation of Rictor. Inactivation of FoxOs results in more potent cell or tumor growth inhibition in response to PI3K-AKT inhibition. These findings have important implications on the treatment strategies of RCC as well as other cancers.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture studies

786-O, UOK101 and RCC4 are human renal cell carcinoma cells, and are described in our previous publication (18). These renal cancer cells and human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), and passaged for less than 6 months after receipt. They are cultured in DMEM + 10% FBS. Lentiviruses or retroviruses were produced in HEK293T cells with packing mix (ViraPower Lentiviral Expression System, Invitrogen) and used to infect target cells per manufacturer's instruction. FoxO1/3/4 L/L, RosaCreERT2 MEFs (18) were isolated from E14.5 embryos by standard methods. Primary FoxO1/3/4 L/L, RosaCreERT2 MEFs were treated with 200 nM 4-OHT or vehicle for 4 days and then shifted to normal medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) after 4-OHT treatment, resulting in FoxO WT and KO MEFs. To measure apoptosis, the cells were stained by Annexin V kit per manufacturer instruction (BD Bioscience) and then subjected to FACS analysis. Cell growth assay was conducted as described in our previous publication (18).

Reagents

Lentiviral shRNA vectors targeting human FoxO1 and FoxO3 were described in our previous publication (18). Rictor retroviral vector and Lentiviral shRNA vector targeting human Rictor were described in the previous publication (38). NVP-BEZ235 was purchased from LC Laboratories. BKM120 was ordered from ChemieTek. MK2206 was ordered from Selleck. 4-OHT was purchased from Sigma. The following antibodies were used in this study: Vinculin (Sigma), FoxO1 (C29H4), FoxO3 (75D8), phospho-FOXO1(Thr24)/FOXO3(Thr32), S6, Ser240/244 phospho-S6, Rictor, AKT, Ser473 phospho-AKT, Thr308 phospho-AKT, GSK3, phospho-GSK3, cleaved caspase-3, Ki67, ERBB3 (all from Cell Signaling Technology).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured in chamber slides overnight and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes. Cells were then blocked for nonspecific binding with 10% goat serum in PBS and 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST), and incubated with the antibody against FoxO1(1:300, Cell signaling) or FoxO3(1:300, Cell signaling) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000, Invitrogen, A11012) for 30 min at room temperature. Coverslips were mounted on slides using anti-fade mounting medium with DAPI. Immunofluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 fluorescence microscope. For each channel, all images were acquired with the same settings.

Western blot analysis and fractionation

Tissues were lysed with RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Sodium Deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS) containing complete mini protease inhibitors (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem). Cultured cells were lysed with NP40 buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 1.0% NP-40, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) containing complete mini protease inhibitors (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem). Western blots were obtained utilizing 20 to 40 µg of lysate protein. Fractionation of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins was done by using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After fractionation, 30µg of protein was used for western blot analysis of FoxOs in the cytoplasm and nucleus. α-tubulin and lamin-A were used as markers of cytoplasm and the nucleus, respectively.

Quantitative real-time PCR and ChIP analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy (Qiagen) and 1st strand cDNA was prepared with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, ABI). Real-time PCR was performed using QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) or TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (ABI), and was run on Stratagene MX3000P. ChIP experiment was performed using EZ-ChIP Kit (Chemicon) per manufacturer's instruction. The primer sequences used in this study are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Xenograft model

786-O cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Once the tumor xenografts reached around 100 mm3, mice were randomized into different groups (n = 5/group) and treated once daily by gavage with vehicle, NVP-BEZ235, BKM120 or MK-2206 (30 mg/kg/day). Drugs were solubilized in one volume of N-methylpyrrolidone (Sigma) and further diluted in nine volumes of PEG 300 (Sigma). Bidimensional tumor measurements were taken; mice were sacrificed after 20 days of treatment, and the tumors were excised for further experiments.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Tumor samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Sigma) overnight, and washed once with 1× PBS and then transferred into 70% ethanol and stored at 4 °C. Tissues were processed by ethanol dehydration and embedded in paraffin by Histology Core Laboratory (MD Anderson Cancer Center) according to standard protocols. Sections (5 µm) were prepared for antibody detection and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed as previously described (18). The protein signal was quantified by Image-pro plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). The immunoreactive signal, corresponding to the target expression level, was calculated based on the average staining intensity and the percentage of positively stained cells.

Results

NVP-BEZ235 treatment-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation is significantly compromised in FoxO deficient cells

Our previous study showed that reactivation of FoxO1 or FoxO3 in renal cancer cells induced potent cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (18). Paradoxically, in the same cell lines, we observed that FoxO reactivation resulted in significantly increased phosphorylation of AKT (data not shown). Since PI3K inhibition generally leads to FoxO activation, we reasoned that FoxOs may also play a role in PI3K inhibition-induced AKT reactivation. We first tested this hypothesis in the matched FoxO WT and KO MEFs generated by transient 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) or vehicle treatment of FoxO1/3/4 L/L, Rosa26-CreERT2 MEFs. Consistent with findings described in other cancer cell lines (33, 35), we observed that treatment with 50 nM NVP-BEZ235, a PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor, in WT MEFs led to transient decrease of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation followed by resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation at later time points (Fig. 1A). NVP-BEZ235 treatment also significantly decreased the phosphorylation levels of AKT substrates such as FoxO and GSK3 (Fig. 1B), and promoted FoxO translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus (Fig. S1), confirming the inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway by NVP-BEZ235. Mirroring the resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, the phosphorylation levels of FoxO and GSK3 also resurged at later time points upon NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. 1B).

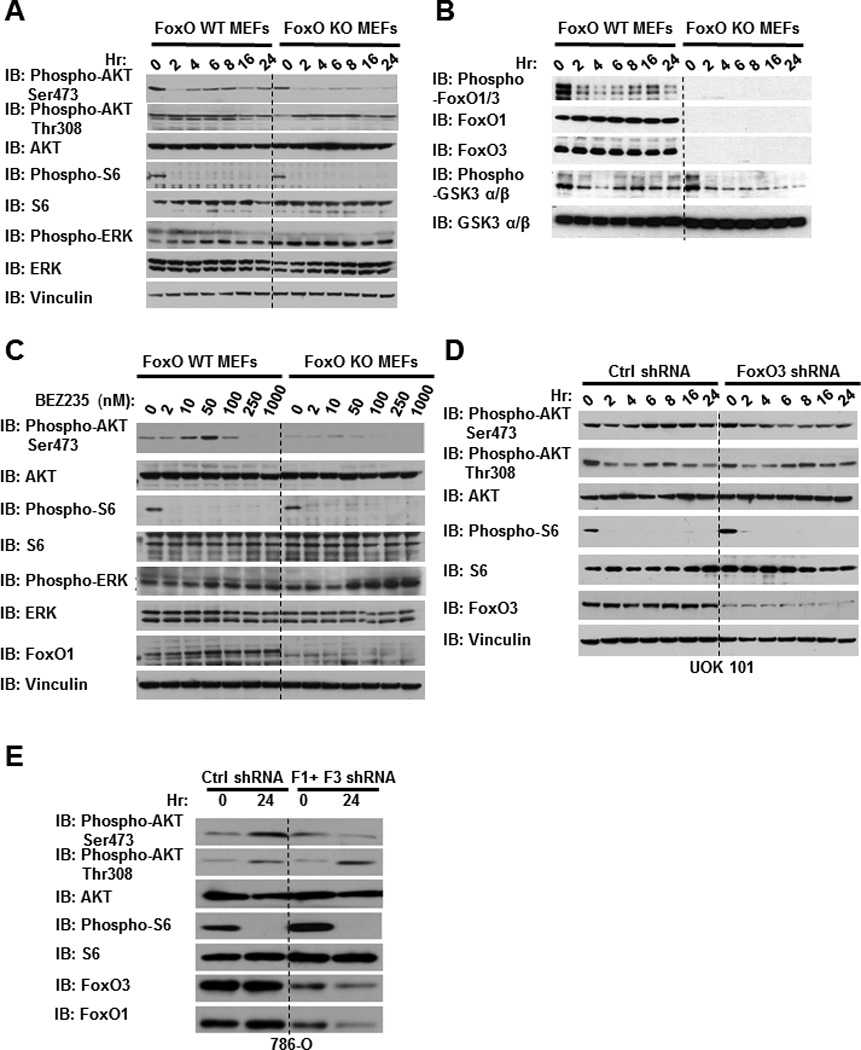

Figure 1. NVP-BEZ235 treatment-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation is significantly compromised in FoxO deficient cells.

(A and B) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different hours as indicated. Cell lysates were then analyzed by western blotting. (C) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours with different concentrations as indicated. Cell lysates were then analyzed by western blotting. (D) UOK 101 cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 10 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different hours as indicated, and then subjected to western blotting analysis. (E) 786-O cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different hours as indicated, and then subjected to western blotting analysis.

Notably, although FoxO deletion in MEFs did not significantly affect the basal level of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, NVP-BEZ235-induced resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation as well as GSK3 phosphorylation at later time points was significantly reduced in FoxO KO MEFs (Fig.1A and 1B, Fig. S2A). A dose-dependent experiment at 24 hours after NVP-BEZ235 treatment revealed that NVP-BEZ235 treatment increased AKT Ser473 phosphorylation at relatively low dosages (less than 100 nM) in WT MEFs, and the increased AKT Ser473 phosphorylation was significantly compromised in FoxO KO MEFs (Fig. 1C). In line with these data from murine system, further experiments in human renal cancer cells (Fig. 1D–1E), including UOK101 (with high expression of FoxO3 and low FoxO1 expression) and 786-O cells (with high expression of both FoxO1 and FoxO3), confirmed that knockdown of FoxOs similarly alleviated NVP-BEZ235-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation.

We also examined the phosphorylation status of several other key signaling molecules in the same experimental conditions. FoxO deletion or knockdown did not significantly affect the levels of S6 phosphorylation under NVP-BEZ235 treatment, suggesting that FoxOs did not affect NVP-BEZ235 inhibition of mTORC1 (Fig. 1A–1E). We found that, in MEFs, 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 treatment did not lead to the initial suppression of AKT Ser308 phosphorylation (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1B), while in UOK101 cells, the kinetics of AKT Thr308 phosphorylation in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment is similar to that of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation with initial suppression followed by resurgence at later time points (Fig. 1D). Regardless of the differential response of AKT Ser308 phosphorylation in different cell lines, we found that FoxO deficiency did not affect AKT Ser308 phosphorylation under NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. 1A, and 1D). Finally, consistent with previous reports in other cell lines (33), NVP-BEZ235 treatment increased ERK phosphorylation, and FoxO deficiency moderately increased ERK phosphorylation under NVP-BEZ235 treatement (Fig.1A and 1C), which may relate to the documented feedback regulation between AKT and ERK pathways. Together, our data reveal that FoxOs specifically promote AKT Ser473 phosphorylation under NVP-BEZ235 treatment, and NVP-BEZ235 treatment-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation is significantly compromised in FoxO deficient cells.

FoxO deficiency promotes cell proliferation suppression and cell death induction under NVP-BEZ235 treatment

AKT activation plays a major role in promoting cell proliferation and survival (3). We thus examined the impact of FoxO deficiency on cell proliferation and survival under NVP-BEZ235 treatment. As shown in Fig. 2A, FoxO deletion rendered MEFs more sensitive to NVP-BEZ235-induced cell proliferation suppression. Although NVP-BEZ235 treatment at 50 nM concentration did not induce obvious apoptosis in WT MEFs, it significantly increased apoptosis in FoxO KO MEFs (Fig. 2B). It is important to note that, when applied at very high dosage (more than 250 nM), NVP-BEZ235 very potently suppressed cell proliferation, and FoxO deficiency did not affect high dose NVP-BEZ235 treatment-induced cell proliferation arrest (Fig. S3). In line with these data from MEFs, further experiments confirmed that knockdown of FoxOs in various human renal cancer cells, although modestly increasing cell proliferation, led to more potent cell proliferation suppression and apoptosis induction compared with control shRNA-infected cells under NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. 2C–2F). Together, our data strongly suggest that FoxO deficiency promotes cell proliferation suppression and apoptosis induction in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment, thus rendering renal cancer cells more susceptible to NVP-BEZ235 treatment.

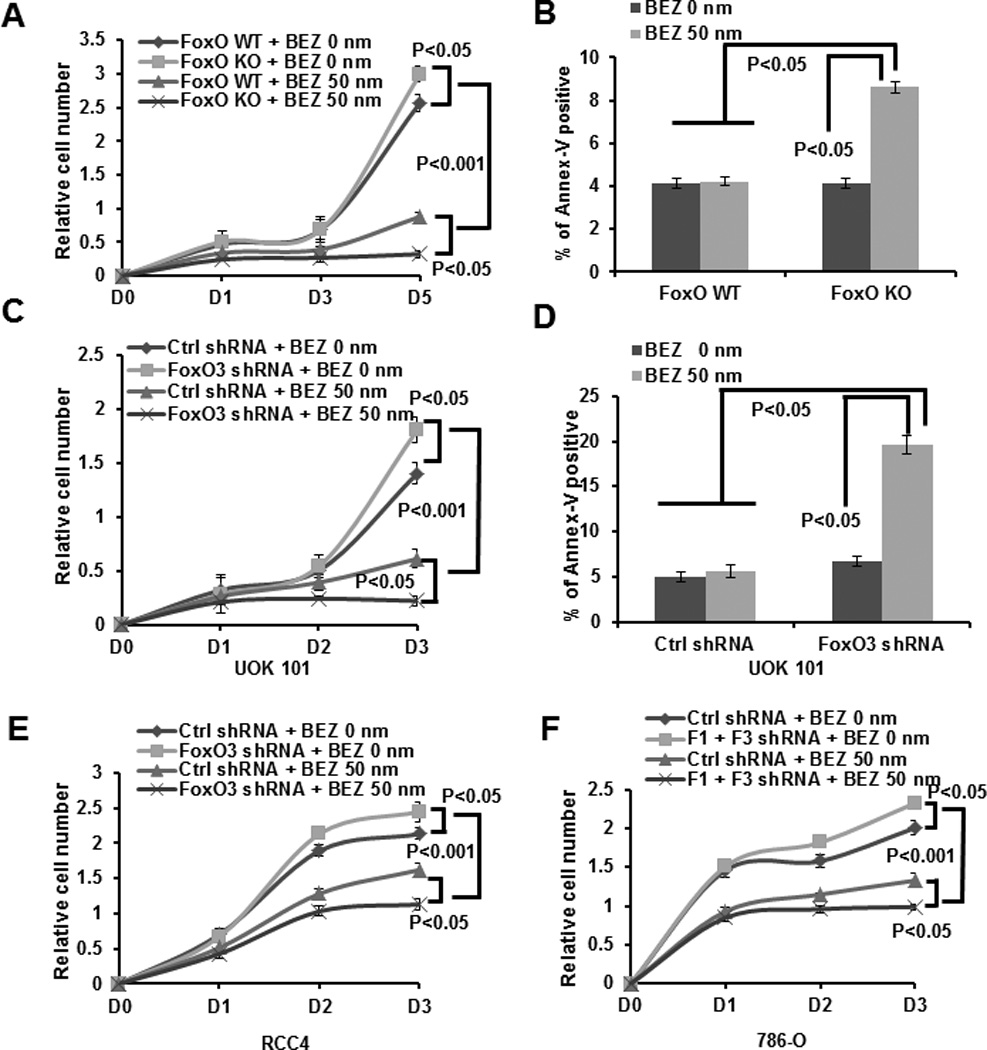

Figure 2. FoxO deficiency promotes cell proliferation suppression and cell death induction under NVP-BEZ235 treatment.

(A) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with 0 (vehicle) or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis. (B) Bar graph showing the percentages of Annexin V staining of FoxO WT and KO MEFs which were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours. (C) UOK 101 cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis. (D) Bar graph showing the percentages of Annexin V staining of UOK101 cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA which were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours. (E) RCC4 cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis. (F) 786-O cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis.

FoxO deficiency potentiates NVP-BEZ235-induced renal tumor suppression in vivo

The data presented above in cell line studies prompted us to further examine the roles of FoxOs in renal tumor growth in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment in vivo using the xenograft model. To this end, we injected the same amount of 786-O cells infected with either FoxO1/3 shRNA or control shRNA into nude mice. Once the tumor xenografts reached 100 mm3, mice were treated once daily with vehicle or NVP-BEZ235 (30 mg/kg/day) for additional 20 days, and the tumor samples were collected for various analyses at the end point. In line with the data from in vitro analyses (Fig. 2F), our in vivo experiments revealed that, while FoxO knockdown moderately increased tumor size and weight in vivo, more dramatic decline in tumor size and weight were observed in FoxO knockdown tumor group compared with control group with NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. 3A–3C).

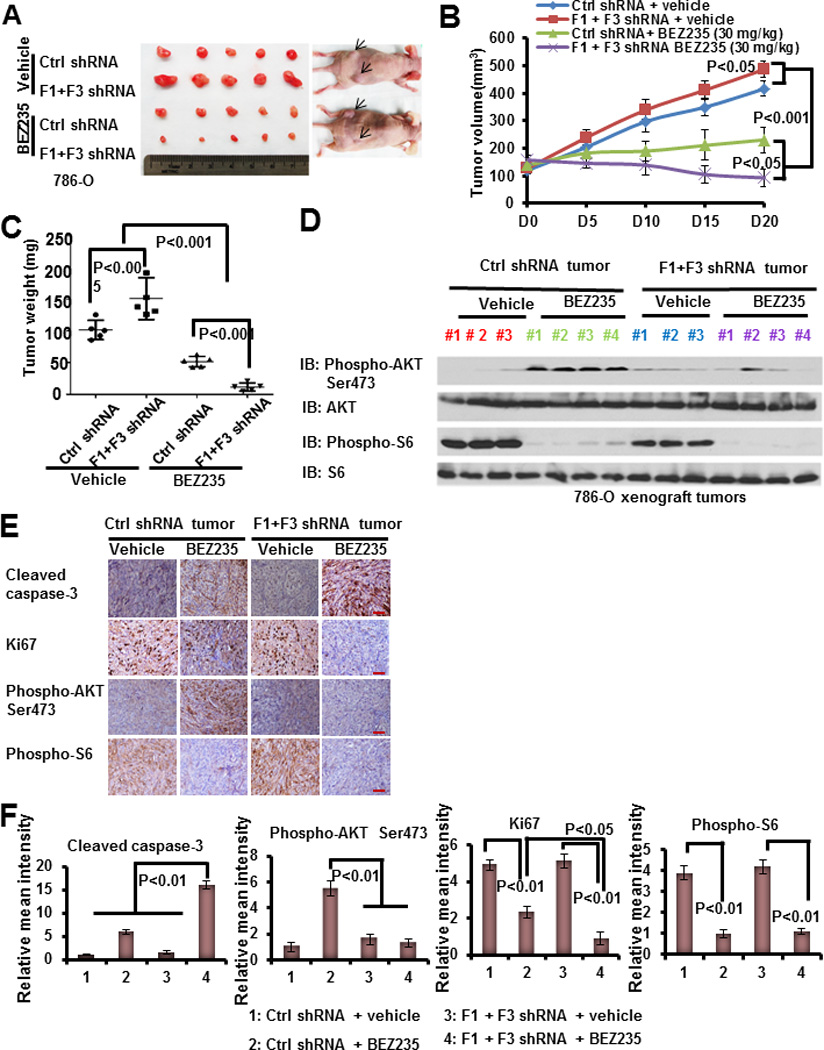

Figure 3. FoxO deficiency potentiates NVP-BEZ235-induced renal tumor suppression in vivo.

(A) The representative images of 786-O xenograft tumors infected with control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA which were treated with vehicle or NVP-BEZ235 for 20 days. (B) Tumor volumes of different tumor and treatment groups at different days during treatment. (C) Tumor weights of different tumor and treatment groups at the end point (20 days after treatment). (D) Protein lysates obtained from different tumor and treatment groups at the end point were subjected to western blotting analysis as indicated. (E) Representative immunohistochemical images showing the staining of tumor samples obtained from different tumor and treatment groups at the end point. Scale bars: 50 um. (F) Bar graphs showing the relative mean intensities of immunohistochemical staining signals quantified by Image-pro plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD).

Further analyses of the tumor samples by western blotting (Fig. 3D) and immunohistochemical experiments (Fig. 3E–3F) confirmed that NVP-BEZ235 significantly induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation in renal tumor samples obtained at end point (20 days after NVP-BEZ235 treatment), and that FoxO knockdown alleviated the increase of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation induced by NVP-BEZ235 treatment in tumors. FoxO knockdown also potentiated NVP-NEZ235 treatment-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in renal tumors, as evidenced by cleaved caspase-3 and Ki67 immunohistochemical analyses (Fig. 3E–3F). It should be pointed out that FoxO knockdown did not affect NVP-BEZ235-induced mTORC1 inactivation as evidenced by S6 phosphorylation (Fig. 3D–3F), which is consistent with the in vitro data (Fig.1A and 1C). Collectively, our data strongly suggest that, under NVP-BEZ235 treatment, FoxOs promote renal tumor growth likely through its upregulation of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, and FoxO deficiency potentiates PI3K inhibition-induced renal tumor suppression in vivo.

FoxOs upregulate Rictor expression under NVP-BEZ235 treatment

Both in vitro and in vivo studies presented above prompted us to further dissect the underlying mechanisms by which FoxOs regulate AKT Ser473 phosphorylation under NVP-BEZ235 treatment. Previous studies showed that FoxOs mediate AKT or PI3K inhibition-induced upregulation of certain RTKs, particularly ERBB3, in breast cancer cells (36), which likely relates to FoxO-mediated AKT reactivation as shown in our studies. However, we found that there was no appreciable difference of ERBB3 expression levels between FoxO WT and FoxO KO MEFs (Fig. 4A).

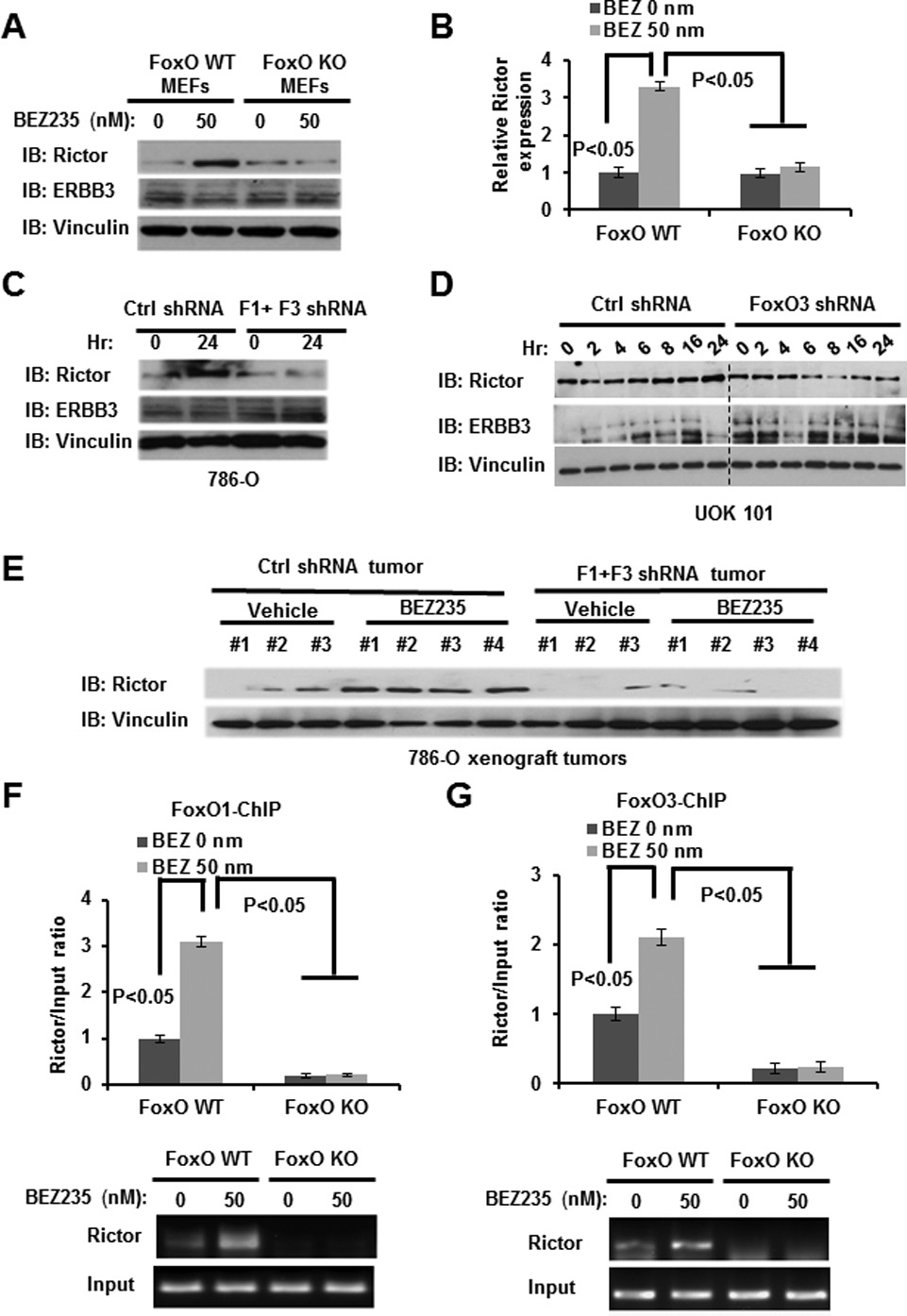

Figure 4. FoxOs upregulate Rictor expression under NVP-BEZ235 treatment.

(A and B) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with 50nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours, and then subjected to western blotting (A) or real-time PCR analysis (B). (C) 786-O cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours, and then subjected to western blotting analysis. (D) UOK 101 cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO3 shRNA were treated with 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different hours as indicated, and then subjected to western blotting analysis. (E) Protein lysates obtained from different tumor and treatment groups at the end point were subjected to western blotting analysis as indicated. (F and G) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours, and then subjected to ChIP analysis to detect FoxO1/3 binding to Rictor promoter. Bar graph showing the relative enrichment determined by real-time PCR following ChIP analysis.

Since our data showed that FoxOs regulate AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, but not AKT Ser308 phosphorylation or S6 phosphorylation, in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. 1A–1E), we reason that FoxOs may specifically regulate mTORC2 function under NVP-BEZ235 treatment, as mTORC2 is responsible for AKT Ser473 phosphorylation (38). To this end, we examined the expression levels of mTORC2 components under NVP-BEZ235 treatment. These analyses revealed that NVP-BEZ235 treatment significantly induced the expression of Rictor, an essential component of mTORC2, in WT MEFs, and that FoxO deletion in MEFs abolished NVP-BEZ235-induced Rictor expression (Fig.4A and 4B). In line with this, FoxO knockdown attenuated NVP-BEZ235-induced Rictor expression in both renal cancer cells in vitro (Fig. 4C–4D) and xenograft renal tumor samples in vivo (Fig. 4E). FoxO knockdown did not affect ERBB3 expression in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment in renal cancer cells (Fig. 4C–4D). Finally, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis documented that endogenous FoxO1 and FoxO3 can directly bind to the FoxO binding element (BE) identified in Rictor promoter region, and NVP-BEZ235 treatment significantly increased FoxO1/3 binding to FoxO BE in Rictor promoter (Fig. 4F–4G). Taken together, our data suggest that, in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment, FoxOs directly bind to Rictor promoter and upregulate Rictor expression, which likely is responsible for the resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation at later time points under NVP-BEZ235 treatment. Our data is also consistent with a previous report showing that overexpression of FoxO is sufficient to induce Rictor expression (39).

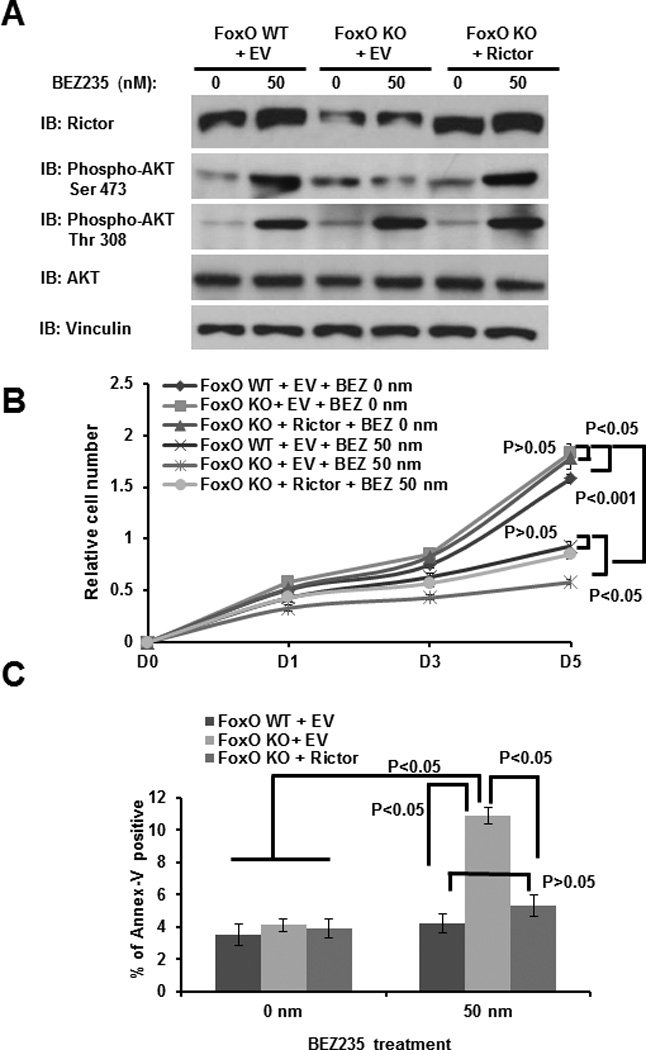

Rictor mediates FoxO regulation of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, cell proliferation and survival in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment

Next we studied whether Rictor plays any causal role in FoxO function in PI3K inhibition-mediated feedback regulation. To this end, we examined whether reexpression of Rictor in FoxO deficient cells would rescue the decrease of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, cell proliferation and survival under NVP-BEZ235 treatment. As shown in Fig. 5A, reexpression of Rictor in FoxO KO cells restored AKT Ser473 phosphorylation to WT level under NVP-BEZ235 treatment. As expected, reexpression of Rictor did not affect AKT Ser308 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). Accordingly, while reexpression of Rictor in FoxO KO cells did not affect cell proliferation or apoptosis under vehicle treatment condition, Rictor reexpression significantly rescued NVP-BEZ235-induced cell proliferation suppression and apoptosis induction phenotypes observed in FoxO KO cells (Fig. 5B–5C). In addition, we showed that knockdown of Rictor in both UOK101 and 786-O renal cancer cells potentiated cell proliferation suppression and cell death induction under NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. S4). Together, our data strongly suggest that Rictor is at least one key downstream target of FoxOs to mediate NVP-BEZ235 -induced feedback regulation.

Figure 5. Rictor mediates FoxO regulation of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation, cell proliferation and survival in response to NVP-BEZ235 treatment.

(A) FoxO WT and KO MEFs with stable expression of either empty vector (EV) or Rictor were treated with 0 or 50nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours, cell lysates were then analyzed by western blotting. (B) FoxO WT and KO MEFs with stable expression of either empty vector (EV) or Rictor were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for different days as indicated, and subjected to cell proliferation analysis. (C) FoxO WT and KO MEFs with stable expression of either empty vector (EV) or Rictor were treated with 0 or 50 nM NVP-BEZ235 for 24 hours. The apoptosis rates of the cells were then detected by Annexin V staining assay.

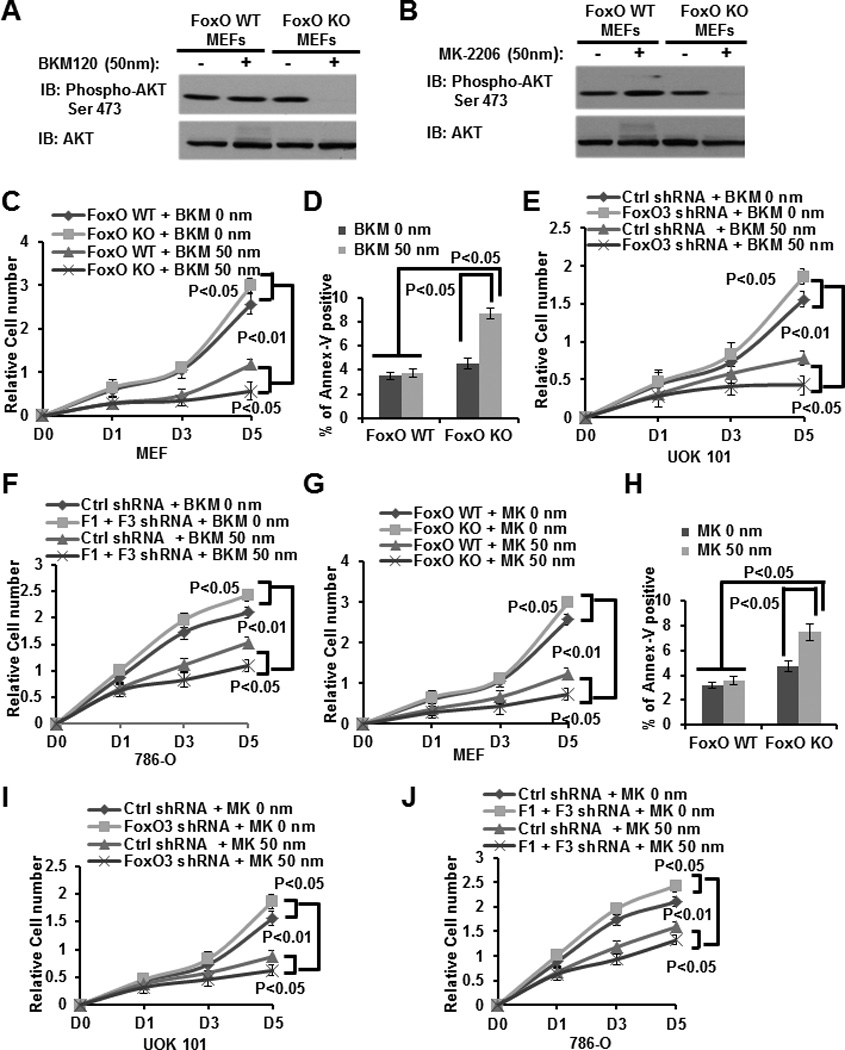

FoxOs modulate the feedback response on AKT Ser473 phosphorylation and renal tumor growth by other PI3K or AKT inhibitors

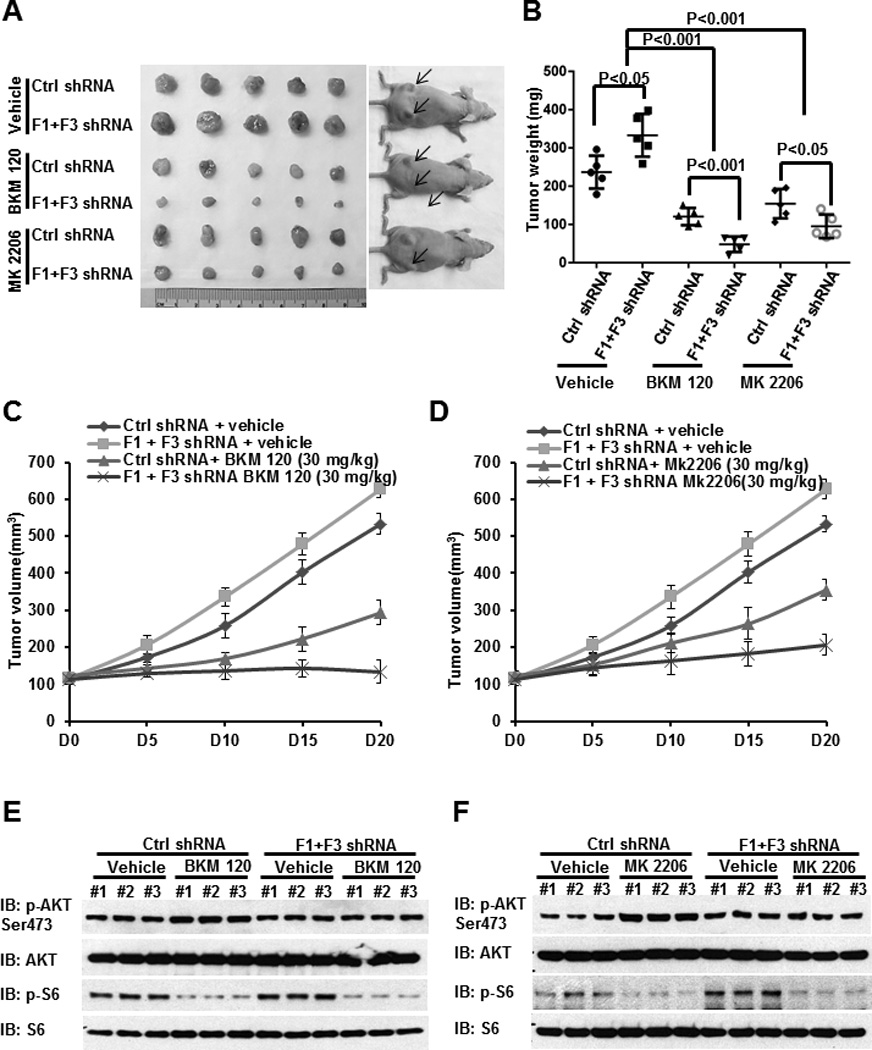

In our data presented above, we use NVP-BEZ235 as a pharmacological means to inhibit PI3K-AKT pathway. To rule out the possibility that the effect is specific to NVP-BEZ235, we also extended our experiments to other PI3K or AKT inhibitors, including BKM120 (a pan-PI3K inhibitor) and MK-2206 (an AKT inhibitor). First, we showed that FoxO KO cells also exhibited significantly reduced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation under the treatment of BKM120 (Fig. 6A) or MK-2206 (Fig. 6B). In addition, our data from different cell lines, including MEFs and renal cancer cells, showed that FoxO deficiency similarly potentiated cell proliferation suppression and cell death induction in response to either BKM120 to MK-2206 treatment (Fig. 6C–6J). Finally, we also examined the roles of FoxOs in renal tumor growth in response to BKM120 or MK-2206 treatment in vivo using the similar xenograft model described above. As shown in Fig. 7A–7F, our data showed that FoxO knockdown potentiated BKM120 or MK-2206 treatment-induced renal tumor suppression in vivo, which aligns well with NVP-BEZ235 treatment data (Fig. 3A–3C). Together, our data strongly suggest that FoxO-mediated feedback regulation described here results from the pharmacological inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway rather than a specific effect of NVP-BEZ235 treatment.

Figure 6. FoxO deficiency potentiates cell proliferation suppression and cell death induction in response to either BKM120 or MK-2206 treatment.

(A and B) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with vehicle, 50 nM BKM120 (A) or 50 nM MK-2206 (B) for 24 hours, and then subjected to western blotting analysis. (C and G) FoxO WT and KO MEFs were treated with 0 (vehicle), or 50 nM BKM120 (C), or 50 nM MK-2206 (G) for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis. (D and H) Bar graph showing the percentages of Annexin V staining of FoxO WT and KO MEFs which were treated with vehicle, or 50 nM BKM120 (D) or MK-2206 (H) for 24 hours. (E and I) UOK 101 cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO3 shRNA were treated with vehicle, or 50 nM BKM120 (E), or MK-2206 (I) for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis. (F and J) 786-O cells infected with either control shRNA or FoxO3 shRNA were treated with vehicle or 50 nM BKM120 (F), or MK-2206 (J) for different days as indicated, and then subjected to cell proliferation analysis.

Figure 7. FoxO deficiency promotes BKM120 or MK-2206 treatment-induced renal tumor suppression in vivo.

(A) The representative images of 786-O xenograft tumors infected with control shRNA or FoxO1/FoxO3 shRNA which were treated with vehicle, BKM120, or MK-2206 for 20 days. (B) Tumor weights of different tumor and treatment groups at the end point (20 days after treatment). (C and D) Tumor volumes of different tumor and treatment groups at different days during drug treatment. (E and F) Protein lysates obtained from different tumor and treatment groups at the end point were subjected to western blotting analysis as indicated.

Discussion

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway is hyperactivated in many human cancers, including RCC. The moderate clinical benefit of the mTOR inhibitor observed in several human cancer clinical trials and the mTORC1 inhibition–mediated feedback activation of PI3K-AKT have prompted ideas for inhibiting the upstream PI3K-AKT in cancer treatment (28). However, the relief of feedback regulation and the resulting activation of other oncogenic signaling pathways caused by PI3K-AKT inhibition likely will limit the clinical utilization of such inhibitors in cancer treatment.

Using NVP-BEZ235 as a pharmacological approach to inhibit PI3K, our study reveals a novel mechanism of PI3K inhibition-induced feedback regulation in RCC cells, which involves FoxO-mediated Rictor upregulation and AKT reactivation via Ser473 phosphorylation. Specifically, our data show that, while short-term treatment of NVP-BEZ235 leads to immediate PI3K-AKT inactivation and FoxO activation, long-term treatment of NVP-BEZ235 leads to FoxO binding to Rictor promoter and upregulation of Rictor expression, resulting in the resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation likely via activation of mTORC2. Since NVP-BEZ235 is a PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor, it should also inhibit mTORC2. However, NVP-BEZ235 treatment at low dosage (such as 50 nM) likely only partially inhibits the activity of mTORC2 (as well as PI3K). We propose that NVP-BEZ235-induced Rictor upregulation will offset the partial inhibitory effect of NVP-BEZ235 on mTORC2, leading to resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation at later time points. When applied at very high dosage (more than 250 nM), we reason that the inhibitory effect of NVP-BEZ235 on mTORC2 and PI3K is so potent that Rictor upregulation will not be enough to offset it. In line with this model, NVP-BEZ235-induced resurgence of AKT Ser473 phosphorylation was only observed at relatively low dosages of NVP-BEZ235 (See Fig. 1C). In addition, the effect of FoxO deficiency on NVP-BEZ235-induced renal cancer growth suppression was only observed at relatively low dosages of NVP-BEZ235 (compare Fig. 2A and Fig. S3). Since drug treatment at high dosages is generally toxic to cancer patients, the observation from our study focusing on low dosages is likely to be of clinical relevance. Finally, we extend our data to other PI3K or AKT inhibitors, suggesting that FoxO-mediated feedback regulation described here likely results from the pharmacological inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway. Whether this mechanism contributes to the tumor recurrence in renal cancer patients receiving PI3K or AKT inhibitor treatment awaits further investigation in the future clinical trials.

Our data showed that FoxOs function to promote cell proliferation and survival under pharmacological inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway, which is different from the anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic function FoxOs exert under other stress conditions (5). Thus, FoxOs could play very different functions by regulating different sets of transcriptional targets under different cell lineages or stimuli, which is in line with a previous report (40). Consistent with this, we found that FoxO deficiency did not affect the expression levels of FoxO targets mediating apoptosis response, such as Bim and p27, under NVP-BEZ235 treatment (Fig. S5).

Our data from both gain-of-function (Rictor reexpression in FoxO deficient cells) and loss-of-function (Rictor knockdown in FoxO proficient cells) experiments identified Rictor as an important downstream target of FoxO to mediate PI3K inhibition-induced feedback. It should be pointed out that moderate overexpression of Rictor in FoxO KO cells did not significantly increase AKT Ser473 phosphorylation under vehicle treatment condition (Fig. 5A), suggesting that NVP-BEZ235-induced AKT Ser473 phosphorylation may involve Rictor and other factors (which may be regulated by PI3K inhibition via FoxO-independent mechanisms). Clearly, the response to pharmacological inhibition of PI3K-AKT pathway may involve multiple mechanisms. Our study strongly suggests that FoxO-Rictor axis is at least one important mechanism involved in this feedback regulation.

Similar to other targeted therapies, it is likely that only a fraction of cancer patients will respond positively to PI3K-AKT inhibition therapy. Thus, it will be critical to identify appropriate biomarker(s) which can be used to stratify cancer patients for PI3K-AKT inhibition treatment. Our study suggests that FoxO may serve as a novel biomarker to stratify renal cancer patients for PI3K or AKT inhibitor treatment. Specifically, since FoxO deficient renal tumors are more sensitive to PI3K-AKT inhibition than FoxO proficient renal tumors, we propose that renal cancer patients with loss of (or low) FoxO expression or activity will respond better to PI3K-AKT inhibition than those with high FoxO expression or activity. In addition, we propose that inhibition of FoxO (or key FoxO targets involved in feedback regulation, such as Rictor) may synergize with PI3K-AKT inhibition in renal cancer treatment. Our study thus challenges the current paradigm of reactivating FoxO in cancer treatment based on FoxO generally being considered as a tumor suppressor. Finally, since the PI3K-AKT pathway is also activated in many other cancers, our data may provide important insights into the treatment of other cancers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors also thank Zhen Xing, Ye Chen, Kingsley Charles V, Xin Wang, and Li Wang for insightful discussion and technical assistance.

Financial Support: This research has been supported by grants from MD Anderson Cancer Center, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Defense (TS093049), Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (RP130020), and Sidney Kimmel Foundation (to B. G). B. G. is a Kimmel Scholar, an Ellison Medical Foundation New Scholar, and a member of the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (CA016672).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002 May 31;296(5573):1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth Control and Disease. Cell. 2012 Apr 13;149(2):274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007 Jun 29;129(7):1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008 Jun 1;412(2):179–190. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2005 Nov 14;24(50):7410–7425. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accili D, Arden KC. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell. 2004 May 14;117(4):421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Gan B, Liu D, Paik JH. FoxO family members in cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011 Aug 15;12(4):253–259. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.4.15954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eijkelenboom A, Burgering BM. FOXOs: signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013 Feb;14(2):83–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304(5670):554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cully M, You H, Levine AJ, Mak TW. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):184–192. doi: 10.1038/nrc1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003 Oct;4(4):257–262. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmena L, Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. Tenets of PTEN tumor suppression. Cell. 2008 May 2;133(3):403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013 Jul 4;499(7456):43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linehan WM, Zbar B. Focus on kidney cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004 Sep;6(3):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rini BI, Campbell SC, Escudier B. Renal cell carcinoma. Lancet. 2009 Mar 28;373(9669):1119–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robb VA, Karbowniczek M, Klein-Szanto AJ, Henske EP. Activation of the mTOR signaling pathway in renal clear cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2007 Jan;177(1):346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pantuck AJ, Seligson DB, Klatte T, Yu H, Leppert JT, Moore L, et al. Prognostic relevance of the mTOR pathway in renal cell carcinoma: implications for molecular patient selection for targeted therapy. Cancer. 2007 Jun 1;109(11):2257–2267. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gan B, Lim C, Chu G, Hua S, Ding Z, Collins M, et al. FoxOs enforce a progression checkpoint to constrain mTORC1-activated renal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010 Nov 16;18(5):472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkins MB, Hidalgo M, Stadler WM, Logan TF, Dutcher JP, Hudes GR, et al. Randomized phase II study of multiple dose levels of CCI-779, a novel mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced refractory renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 1;22(5):909–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007 May 31;356(22):2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008 Aug 9;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Defining the role of mTOR in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007 Jul;12(1):9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004 Aug 15;18(16):1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Um SH, D'Alessio D, Thomas G. Nutrient overload, insulin resistance, and ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, S6K1. Cell Metab. 2006 Jun;3(6):393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhaskar PT, Hay N. The two TORCs and Akt. Dev Cell. 2007 Apr;12(4):487–502. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning BD. Balancing Akt with S6K: implications for both metabolic diseases and tumorigenesis. J Cell Biol. 2004 Nov 8;167(3):399–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006 Feb 1;66(3):1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006 May 25;441(7092):424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009 Aug;9(8):550–562. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho DC, Cohen MB, Panka DJ, Collins M, Ghebremichael M, Atkins MB, et al. The efficacy of the novel dual PI3-kinase/mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 compared with rapamycin in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010 Jul 15;16(14):3628–3638. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maira SM, Stauffer F, Brueggen J, Furet P, Schnell C, Fritsch C, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BEZ235, a new orally available dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor with potent in vivo antitumor activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008 Jul;7(7):1851–1863. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Chen Y, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011 May 17;19(5):575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serra V, Scaltriti M, Prudkin L, Eichhorn PJ, Ibrahim YH, Chandarlapaty S, et al. PI3K inhibition results in enhanced HER signaling and acquired ERK dependency in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011 Jun 2;30(22):2547–2557. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008 Dec;14(12):1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serra V, Markman B, Scaltriti M, Eichhorn PJ, Valero V, Guzman M, et al. NVP-BEZ235, a dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, prevents PI3K signaling and inhibits the growth of cancer cells with activating PI3K mutations. Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 1;68(19):8022–8030. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Scaltriti M, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Grbovic-Huezo O, Serra V, et al. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell. 2011 Jan 18;19(1):58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muranen T, Selfors LM, Worster DT, Iwanicki MP, Song L, Morales FC, et al. Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR leads to adaptive resistance in matrix-attached cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2012 Feb 14;21(2):227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005 Feb 18;307(5712):1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen CC, Jeon SM, Bhaskar PT, Nogueira V, Sundararajan D, Tonic I, et al. FoxOs inhibit mTORC1 and activate Akt by inducing the expression of Sestrin3 and Rictor. Dev Cell. 2010 Apr 20;18(4):592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y, Ding Z, et al. FoxOs are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 2007 Jan 26;128(2):309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.