Abstract

Emerging research has begun to examine cognitive and interpersonal predictors of stress and subsequent depression in adolescents. This research is critical as cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability factors likely shape expectations, perspectives, and interpretations of a given situation prior to the onset of a stressor. In the current study, adolescents (n=157; boys=64, girls=93), ages 12 to 18, participated in a 6-month, multi-wave longitudinal study examining the impact of negative cognitive style, self-criticism, and dependency on stress and depression. Results of time-lagged, idiographic multilevel analyses indicate that depressogenic attributional styles (i.e., composite score and weakest link approach) and self-criticism predict dependent interpersonal, but not noninterpersonal stress. Moreover, the occurrence of stress mediates the relationship between cognitive vulnerability and depressive symptoms over time. At the same time, self-criticism predicts above and beyond depressogenic attributional styles (i.e., composite and weakest link approach). In contrast to our hypotheses, dependency does not contribute to the occurrence of stress, and additionally, no gender differences emerge. Taken together, the findings suggest that self-criticism may be a particularly damaging vulnerability factor in adolescence, and moreover, it may warrant greater attention in the context of psychotherapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Hopelessness Theory, Depressogenic Attributional Style, Weakest Link, Self-Criticism, Dependency, Stress Generation

Adolescence is the peak period for the emergence of depression (Hankin et al., 1998), and depressive episodes in youth often trigger debilitating ripples across emotional and socioeconomic domains (Greden, 2001). Given the alarmingly high prevalence rate of adolescent depression as well as the associated negative consequences (Merikangas & Knight, 2009), researchers have sought to identify core etiological components that underlie major depressive disorder (MDD). Most notably, cognitive vulnerability models of depression have received widespread support across children and adolescents (see Abela & Hankin, 2008), and researchers have examined an array of cognitive vulnerability factors including but not limited to dysfunctional attitudes (Abela & D'Alessandro, 2002), hopelessness (Abela, 2001; Hankin, Abramson, & Siler, 2001), and self-criticism (Adams, Abela, Auerbach, & Skitch, 2009). Consistent with Beck’s (1983) cognitive theory of depression, these models have been examined in the context of a diathesis-stress framework, which posits that the interaction between stress and premorbid vulnerability factors confers risk for depression. As a whole, these cognitive vulnerability models have provided critical insight regarding the onset and maintenance of adolescent MDD (Abela & Hankin, 2008). At the same time, a potential limitation of the diathesis-stress framework is an inability to account for how or why stress arises, which is notable as adolescents generate a greater number of interpersonal stressors relative to children and adults (Rudolph, 2008) and possess certain characteristics that contribute to the occurrence of stress and depression (Auerbach, Eberhart, & Abela, 2010; Auerbach & Ho, 2012).

Adolescent Stress Generation

Stress generation has been described as an action model as individuals possess certain beliefs, characteristics, and/or engage in specific patterns of behaviors that contribute to the occurrence of negative life events, in particular dependent events that are influenced by the individual. Over time, these events are believed to lead to the development or recurrence of MDD (Hammen, 1991). Thus, in comparison to the diathesis-stress perspective, which implicitly assumes that adolescents are passive recipients of stress, the stress generation framework asserts that there is a transactional relationship between stress and depression (Alloy, Liu, & Bender, 2010). Initial examinations of the stress generation framework found that a history of depression in adult women contributed to the occurrence of dependent interpersonal stressors, which increased susceptibility to future depressive episodes (Hammen, 1991, 2005). More recent research has expanded this seminal work implicating the stress generation effect in adolescent depression symptoms (Shih, Abela, & Starrs, 2009) and diagnoses (Harkness & Stewart, 2009). In light of these promising findings, researchers have begun to examine additional factors that may trigger the stress generation effect in adolescents.

Depressogenic cognitive styles consolidate during adolescence (Hankin et al., 2009), and therefore, it may represent an opportune time to determine whether these mechanisms potentiate the stress generation effect during a developmentally challenging period. To date, several cognitive vulnerability factors have been implicated in the stress generation process including hopelessness (Joiner, Wingate, & Otamendi, 2005), negative inferential styles (Shih et al., 2009), perceived control (Auerbach et al., 2010), and self-criticism (Shahar & Priel, 2003). These findings suggest that preexisting depressogenic factors shape the type of negative life events that occur in the context of an adolescent’s life, and in some instances, confer elevated risk for depressive symptoms. In contrast to the diathesis-stress framework, the stress generation perspective suggests that, for some, depressogenic cognitive styles may be more active rather than dormant outside the presence of stress. Meaning, different cognitive styles may impact an individual’s expectations, perspectives, and interpretations of a given situation prior to the onset of a stressor. Thus, individuals’ cognitive characteristics may shape their interactions in such a way that they generate greater interpersonal stress. For example, in self-critical adolescents expecting confirmatory peer criticism, preemptive hostility may accord emotional distance, which buffers against the possibility of impending critiques. While this hostility may afford a degree of self-preservation, the maladaptive approach may also fuel interpersonal discord, which over time may lead to interpersonal loss and subsequent depression.

The early research examining cognitive vulnerability predictors of stress generation has shown promising results; however, important questions remain. First, a potential limitation of past research is the examination of cognitive vulnerability factors in isolation despite conceptual, theoretical, and statistical overlap among different cognitive vulnerabilities (see Hankin et al., 2009). Therefore, it is essential to delineate whether each cognitive factor provides unique vulnerability for the emergence of adolescent depression, or alternatively, whether different vulnerability factors collectively confer vulnerability to depressive symptoms in youth. Second, one of the core tenants of stress generation research is the manifestation of dependent interpersonal as opposed to noninterpersonal events. Some research has indicated that underlying cognitive diatheses predict dependent interpersonal stressors (Auerbach et al., 2010; Joiner et al., 2005; Shih et al., 2009) while others have found non-specificity (Shahar & Priel, 2003). Therefore, further research is warranted to address whether depressogenic cognitive diatheses contribute to dependent interpersonal as opposed to noninterpersonal stressors. To address these gaps in the literature, the current study will examine the role of depressogenic attributional styles and self-criticism to determine whether the presence of these factors uniquely or collectively contribute to the development of interpersonal stress and subsequent depressive symptoms.

Hopelessness Theory: Composite versus Weakest Link Approach

The hopelessness theory of depression, a diathesis-stress model, posits that the tendency to make negative attributions following the occurrence of stressors confers risk for the onset of MDD (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). Specifically, it is believed that depressogenic attributions increase vulnerability to depression among individuals who: (a) make global and stable attributions following negative events, (b) believe negative events will have catastrophic consequences, and (c) view the self as flawed in response to negative events. To date, the hopelessness theory of depression has received widespread support in children and adolescents (Abela, 2001; Abela & Sarin, 2002; Hankin et al., 2001), and in recent years, researchers have sought to unpack the hopelessness theory by utilizing both a composite score (Haeffel et al., 2008) and weakest link (Abela & Sarin, 2002) approach to determine whether an individual’s degree of vulnerability is best represented by assessing multiple domains of vulnerability (i.e., composite vulnerability across negative cause, consequences, and self attributions) or alternatively, whether vulnerability is best reflected through one’s most maladaptive cognitive style (i.e., weakest link). While there has been support for both of these approaches, Reilly and colleagues (2012) recently conducted a comparison study in young adults and found that the weakest link model, within a diathesis-stress framework, predicted above and beyond the composite approach when predicting the onset of depressive symptoms (Reilly, Ciesla, Felton, Weitlauf, & Anderson, 2012). At the same time, research is warranted to compare these approaches in the context of a more action-oriented framework, especially among adolescents.

Although the hopelessness theory of depression was originally conceptualized as a diathesis-stress model (Abramson et al., 1989), negative cognitive styles also play a prominent role in the stress generation process. Depressogenic styles are believed to influence expectations and perceptions of one’s own environment, and as a result, likely shape the types of stressors one experiences. For example, in women but not men, Safford and colleagues (2007) found that relative to college students reporting positive cognitive styles, students with negative cognitive styles reported a greater number of dependent interpersonal but not achievement-related events. Similarly, in a sample of children of affectively ill parents, Shih and colleagues (2009) found that negative inferential styles, as assessed through a weakest link approach, prospectively predicted interpersonal, but not noninterpersonal, stressors at a 1-year follow-up assessment (Shih et al., 2009). Shih et al. elected to use a weakest link approach given that inferential styles are thought to be relatively independent of one another among younger individuals (Abela & Hankin, 2008), but their approach does not allow us to delineate the relative merits of a composite versus a weakest link approach. Consequently, the current study examined whether depressogenic factors contributed to interpersonal, but not noninterpersonal stress, and subsequent depressive symptoms using both a composite and weakest link framework. Further, as past research has found that stress generation effects often vary as a function of gender with girls reporting greater dependent interpersonal stressors (for a review, see Hammen, 2005), we also hypothesized that relative to boys, a negative cognitive style among girls would generate a greater number of dependent interpersonal stressors, and then contribute to higher levels of depressive symptoms.

Delineating the Role of Self-Criticism and Dependency

According to Blatt and Zuroff (1992), self-criticism and dependency play a central role in the onset and maintenance of MDD. Whereas highly self-critical individuals have a need to satisfy or exceed self- and/or other-expectations in order to maintain well-being, individuals reporting excessive levels of dependency, an interpersonal vulnerability factor, derive well-being through relational connectedness and (excessive) reassurance of their value from close relationships (Adams et al., 2009; Blatt & Zuroff, 1992). Adams and colleagues (2009) report that in youth both self-criticism and dependency lead to higher depressive symptoms following the occurrence of negative life events. Analyses also indicate that in the context of a diathesis-stress framework, each vulnerability factor remains significant while statistically controlling for the other, suggesting that both self-criticism and dependency may confer unique vulnerability to depression among youth. At the same time, less is known about whether self-criticism and dependency contribute to a stress generation effect, especially among adolescents.

To date, research in university students (self-criticism - Blankstein & Dunkley, 2002; Dunkley, Zuroff, & Blankstein, 2003, 2006; Shahar, Joiner, Zuroff, & Blatt, 2004; dependency - Shih & Eberhart, 2010) and adults (self-criticism – Cox, Clara, & Enns, 2009; Priel & Shahar, 2000); dependency - Zuroff, Moskowitz, & Cote, 1999) demonstrates that both self-criticism and dependency generate stressful life events. Comparatively less research, however, has been conducted in youth. Shahar and Priel (2003) report that both self-criticism and dependency prospectively generate negative life events. Nevertheless, the study did not disentangle dependent interpersonal versus noninterpersonal stressors. In contrast, Shih et al. (2009) state that self-criticism, but not dependency, is associated with greater dependent interpersonal stress in children of affectively ill parents. At the same time, both self-criticism and dependency prospectively predict changes in dependent noninterpersonal stressors at the 1-year follow-up assessment. Taken together, further research is warranted to reconcile these mixed findings. In the current study, we hypothesized that consistent with the adult literature, self-criticism and dependency would generate dependent interpersonal but not non-interpersonal stressors. Further, expanding on research conducted by Shahar and Priel (2003) and Shih et al. (2009), we hypothesized that dependent interpersonal stressors would mediate the relationship between self-criticism and dependency and subsequent depressive symptoms over time.

Goals of the Current Study

In the current study, adolescents (n=157) participated in a multi-wave, longitudinal design over a 6-month period to examine whether depressogenic cognitive styles and/or interpersonal factors contributed to stress and depressive symptoms over time. First, a growing body of literature supports the role of cognitive vulnerability factors contributing to dependent interpersonal as opposed to noninterpersonal stressors in youth (Joiner et al., 2005; Shih et al., 2009). Nevertheless, research is warranted to delineate whether individuals are at increased risk by virtue of their most depressogenic attributional style (i.e., weakest link) or whether adolescents are more vulnerable as a function of aggregate vulnerabilities across attributional style domains (i.e., composite score or negative cognitive style). We hypothesized that both that a composite negative cognitive style and weakest link approach would predict dependent interpersonal, but not noninterpersonal stressors, and moreover, these stressors would then contribute to higher levels of depressive symptoms over time. Second, in comparison to self-criticism, dependency has been a less consistent predictor of the stress and depression. Yet, adolescence is a period in which peer relationships are more central (Rudolph, 2008), and therefore, we believe that it likely plays a more prominent role in the manifestation of both interpersonal stress and subsequent depressive symptoms. Therefore, we hypothesized that among adolescents both self-criticism and dependency will generate greater dependent interpersonal stress, which in turn, will lead to greater levels of depressive symptoms. Third, it is important to examine whether cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability factors predict above and beyond one another to determine if these factors are predicting unique variance with respect to changes in dependent interpersonal stressors and depressive symptoms over time. As both cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability each play a role in the manifestation of depressive symptoms, we hypothesized that within the same model, cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability factors would each exert an effect. Moreover, we believe that dependent interpersonal, but not noninterpersonal, stressors would mediate the relationship between these vulnerability factors and depressive symptoms over time. Last, gender differences in depression arise during adolescence and persist throughout adulthood (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007). We hypothesized that cognitive and interpersonal models will be significant in male and female adolescents, and within these models, we believe that relative to males, females would report higher levels of dependent interpersonal stressors and depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

The current study includes adolescents (n=157; boys=64, girls=93) from an urban environment in a middle-income school district (i.e., median income: $35,000 – $50,000 (Canadian dollars)). Ages range from 12 to 18 (Mean=13.99, SD=1.43), and the ethnic distribution, which is in line with the urban community, indicates: 81.5% Caucasian, 10.2% Asian, 3.2% Black, 1.9% Hispanic, and 3.2% reported other.

Procedure

The university IRB provided approval for the project. Every effort was made to include all students within the school; however, only adolescents who provided both parent consent and adolescent assent were included. Reasons for non-participation were not assessed in order to ensure the privacy of families. At baseline, participants completed self-report measures assessing depression, stress, negative cognitive style, self-criticism, and dependency. Additionally, four follow-up assessments were completed every 6 weeks over the course of twenty-four weeks (6 months), and participants provided self-report data pertaining to depressive symptoms and stress. All assessments were completed during a free period in school. Average participant retention during the four follow-up assessments was 79%. Participants included in the final sample completed a minimum of 3 of 5 assessments to obtain a reliable mean estimate of stress and depressive symptoms. Finally, the analyses presented in the current manuscript are from a large dataset that examined underlying factors that predict the onset of anxiety and depressive disorders in youth. The aims of the current manuscript are unique in its effort to identify cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability factors that predict dependent interpersonal as opposed to noninterpersonal stressors and subsequent depressive symptoms.

Measures

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977)

The CES-D is a twenty item self-report measure that assesses levels of depressive symptoms during the past week. Examples of questions include: “I felt sad,” “I felt hopeless about the future,” and “I did not enjoy life.” Items on the scale range from 0 (none of the time) to 3 (all of the time) with possible total scores ranging from 0 – 60, and higher scores reflect greater depressive symptoms. Numerous studies have shown that the CES-D has strong test-retest reliability and high correlations with other measures of depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1991). The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample ranges from .90 to .94 suggesting strong internal consistency.

Adolescent Life Events Questionnaire - Revised (ALEQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002)

The ALEQ is a fifty-seven item self-report instrument that was developed to assess a broad range of negative life events occurring in the past month. For all items, participants rated how often such events occurred on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), and higher scores reflected a greater number of negative life events. In previous research (Auerbach et al., 2010), a consensus team including 2 psychologists and 2 advanced doctoral students rated whether items were: (a) dependent (i.e., at least in part dependent on the actions of the individual), (b) interpersonal, and (c) noninterpersonal. It is important to note that only interpersonal events were rated as dependent as more contextual information would be needed for coding noninterpersonal events. Items were retained only if there was unanimous agreement, and items were excluded when a consensus could not be reached. Twenty-nine items were rated as both dependent and interpersonal and exemplar items are, “You fought with your parents over your personal goals, desires, or choice of friends,” and “You had an argument with a close friend.” The consensus team also rated thirteen items as noninterpersonal. Example items include, “A close family member lost their job” and “You did poorly on or failed a test or class project.” While life events are not hypothesized to cohere in a subscale, we, nevertheless, estimated the internal consistency for both the dependent interpersonal and noninterpersonal subscales. In this sample, the internal consistency for dependent interpersonal stressors ranges from .89 to .91 suggesting strong internal consistency. Noninterpersonal stressors, by contrast, range from .69 to .80.

Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire (ACSQ; Hankin & Abramson, 2002)

The adolescent cognitive style questionnaire assesses cognitive vulnerability including negative inferences for cause, consequence, and self. The ACSQ is composed of twelve hypothetical negative life event scenarios (a) across interpersonal and achievement domains and (b) relevant to adolescents. Examples of events include, “You take a test and get a bad grade” and “Someone says something bad about how you look.” First, participants are provided with the hypothetical event, and are asked to provide one cause for the event. Then, participants rate the degree to which the cause of the event is internal, stable, and global. Items on the ACSQ range from 1 to 7, and the average response across items within a given subscale is computed. In line with the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson et al., 1989), the negative attributions for cause, or the generality subscale, was calculated by taking the average of the global and stable subscales, and did not include the internal item responses. Second, participants rate the likelihood that future consequences will result from the negative event (i.e., negative attributions of consequences). Last, participants rate whether the occurrence of the event signifies whether the self is flawed (i.e., negative attributions of self). Given the high correlation among the three subscales (average r = .79), a composite variable was created, negative cognitive style, which was operationalized as the average score for the three subscales. Analyses also examined the impact of the weakest link approach, and we identified participants’ most vulnerable attributional style. Each participant’s weakest link score was represented by the highest attributional style subscale score (i.e., higher scores connote greater cognitive vulnerability), and within the sample, the weakest link distribution included: 10% - consequences, 22% - self, and 68% - cause (see full description Abela & Sarin, 2002). In this sample, the Cronbach’s alpha for the instrument is .94, which suggests strong internal consistency.

Children’s Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (CDEQ; Abela & Taylor, 2003)

The CDEQ is a twenty item measure that assesses dependency and self–criticism in youth. Participants responded to statements about themselves using the following scale: “not true for me,” “sort of true for me,” and “really true for me.” Higher scores indicate higher levels of dependency or self-criticism. The CDEQ is modeled after the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (Blatt, D'Afflitti, & Quinlan, 1976), which is used to assess dependency and self–criticism in adults. Past research suggests that self-criticism predicts increases in depressive symptoms over time, and scores for self-criticism and dependency are positively correlated with depressive symptoms (Abela & Taylor, 2003). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha in this sample is .57 for self-criticism and .68 for dependency, indicating modest internal consistency.

Data Analytic Overview

The proposed idiographic time-lagged, multilevel mediation models were analyzed using the guidelines provided by Bauer, Preacher, and Gil (2006). This approach is preferable to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) step-by-step approach, which assumes that each model step is independent. Moreover, it allows for the inclusion of repeated measures and directly estimates the covariance of the random effects from different Level I and Level II models (see Auerbach et al., 2010). To determine whether random effects should be included within our model, we estimated an unconditional growth curve that included time as a predictor of depressive symptoms. The inclusion of random, as opposed to fixed, effects for the intercept and the slope are important as the random effects more effectively: (a) estimate correlations among the Level I variables and (b) model differences of the impact from Level II variables (i.e., cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability predictors) on outcome variables (i.e., mediator – stress; dependent variable – depressive symptoms). Thus, random effects are of particular import when using an idiographic, multilevel mediation approach.

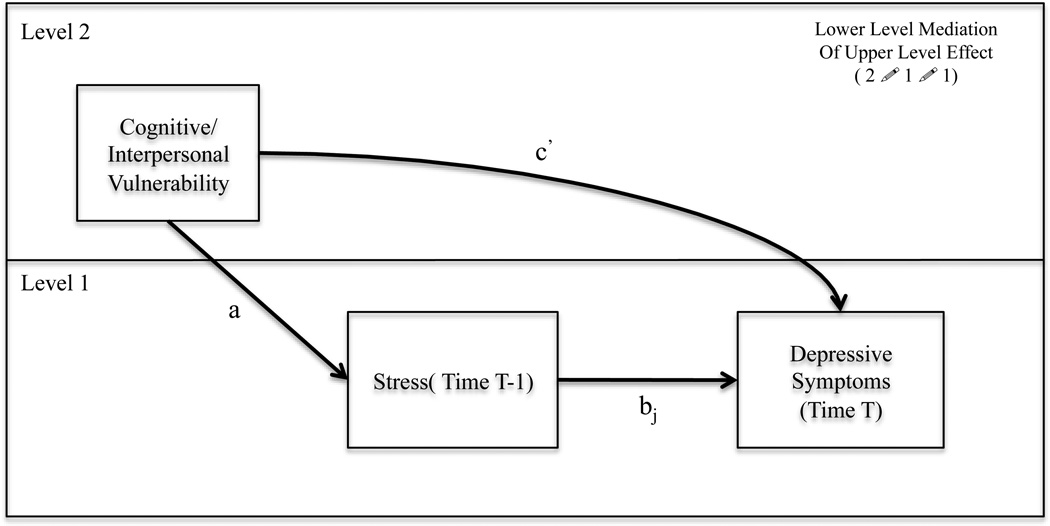

To examine whether stress (i.e., dependent interpersonal or noninterpersonal) mediates the relationship between cognitive/interpersonal vulnerability (i.e., negative cognitive style, weakest link, self-criticism, or dependency) and subsequent depressive symptoms (see Figure 1), we utilized SAS version 9.2. The dependent variable is within-subject fluctuations in depressive symptoms, which is a Level I variable. The independent variable for the proposed mediation model is cognitive/interpersonal vulnerability, a between-subject factor and Level II variable. The mediator is within-subject fluctuations in stress, a Level I variable. In order to calculate the indirect effect of the proposed mediation model, the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the mediation effect was computed using Bauer et al.’s (2006) formula. Consistent with past literature, the mediation effect is considered statistically significant if zero is not included in the CI. In addition to the factors above, the following effects were also included in the model. First, to control for individual differences in baseline levels of depressive symptoms and stress (i.e., interpersonal and noninterpersonal), a participant’s initial depressive symptoms and stress were included in the model. Second, to account for individual variability in the average level of depressive symptoms at a given participant’s mean stress (i.e., interpersonal and noninterpersonal), a random effect for intercept was included in the model. Third, stress (i.e., interpersonal and noninterpersonal) is a within-subject predictor whose effect is expected to vary from participant to participant, a random effect for slope is included in the model. Last, gender differences were examined among significant mediation models. Specifically, analyses examined whether gender moderated the pathways leading to stress and depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Idiographic, Time-Lagged Multilevel Mediation Model: Stress as a Mediator of Cognitive/Interpersonal Vulnerability and Depressive Symptoms

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides information regarding bivariate correlations among baseline instruments. Not surprisingly, there was a high correlation among cognitive/interpersonal vulnerability factors and depressive symptoms. Additionally, the table provides information regarding means, standard deviations, and range of baseline measures.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Baseline Instruments

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Negative Cognitive Style | -- | ||||||

| 2. Weakest Link | .95*** | -- | |||||

| 3. Self-Criticism | .35*** | .33*** | -- | ||||

| 4. Dependency | .26*** | .24** | .40*** | -- | |||

| 5. Initial Depressive Symptoms | .34*** | .35*** | .42*** | .21* | -- | ||

| 6. Initial Dependent Interpersonal Stress | .33*** | .35*** | .47*** | .15 | .62*** | -- | |

| 7. Initial Noninterpersonal Stress | .27** | .28*** | .37*** | .13 | .43*** | .71*** | -- |

| Mean | 2.55 | 3.06 | 34.35 | 43.96 | 14.82 | 55.49 | 26.94 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.99 | 1.03 | 7.34 | 8.73 | 12.35 | 15.52 | 6.92 |

| Low | 1 | 1 | 16 | 25 | 0 | 29 | 13 |

| High | 5 | 5 | 55 | 67 | 52 | 105 | 47 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Main Effect Models

Preliminary multilevel models examined whether negative cognitive style, weakest link, self-criticism, and dependency prospectively predict depressive symptoms over time. Each model was estimated separately and included age and gender as covariates. Additionally, the models included an autoregressive covariance structure and random intercept. Results indicated that each of the following prospectively predict depressive symptoms: (a) negative cognitive style composite score (b = 4.27, SE = 0.75, t(152) = 4.27, p < .0001), (b) weakest link (b = 3.25, SE = 0.75, t(152) = 4.35, p < .0001), (c) self-criticism (b = 4.07, SE = 0.72, t(168) = 5.66, p < .0001), (d) dependency (b = 1.58, SE = 0.75, t(149) = 2.12, p = 0.04). Additionally, results from an unconditional growth curve model that included time as a predictor of depressive symptoms indicates that there is significant variation in both the intercept (b = 35.40, SE = 0.90, t(151) = 39.39, p < .0001) and slope (b = −0.63, SE = 0.30, t(461) = −2.10, p < .05) of depressive symptoms over time. In light of our main effect and unconditional growth curve models, time-lagged, multilevel mediation models were estimated.

Time-Lagged Mediation Models Including Negative Cognitive Style and Weakest Link

As negative cognitive style composite score prospectively predicts depressive symptoms, we next examined whether dependent interpersonal stress(Time T-1) mediates the relationship between a composite score and subsequent depressive symptoms(Time T). In order to do so, we utilized a single simultaneous approach (see Auerbach et al., 2010; Bauer et al., 2006). The model included an autoregressive heterogeneous covariance structure as well as random effects (i.e., slope and intercept). Notably, the negative cognitive style composite score predicts higher levels of dependent interpersonal stress (path a: b = 3.59, SE = 1.10, t(912) = 3.26, p = 0.001), and after controlling for the proportion of variance in dependent interpersonal stress(Time T-1) predicting depressive symptoms(Time T) (path b: b = 0.15, SE = 0.03, t(912) = 4.47, p < 0.0001), higher levels of such stress(Time T-1) mediate the relationship between negative cognitive style and depressive symptoms(Time T) (path c: b = 0.24, SE = 0.58, t(912) = 0.42, p = 0.67). The 95% CI (path a*bj: b = 0.54, SE = 0.21; 0.13, 0.94) suggests that the mediation effect is significant.

A single simultaneous model was also utilized to examine the impact of the weakest link approach, and the model included an autoregressive covariance structure as well as random effects for slope and intercept. Similar to the composite score approach, the weakest link predicts higher levels of depressive symptoms (path a: b = 3.72, SE = 1.10, t(911) = 3.38, p = 0.0007). When controlling for the proportion of variance accounted for in the pathway between dependent interpersonal stress(Time T-1) and depressive symptoms(Time T) (path b: b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, t(911) = 2.53, p = 0.01), such stress(Time T-1) partially mediates the relationship between the weakest link and subsequent depressive symptoms(Time T-1) (path c: b = 2.17, SE = 0.67, t(911) = 3.23, p = 0.001). Again, the 95% CI was utilized in order to examine the indirect effect. Results indicated that the mediation effect is significant (path a*bj: b = 0.31, SE = 0.16; 0.003, 0.62).

Each of the models above was also examined with: (a) negative cognitive style composite score or weakest link as the independent variable, (b) noninterpersonal stress as a mediator, and (c) depressive symptoms as the dependent variable. When estimating the fixed effects for these models, the pathway between noninterpersonal stress(Time T-1) and subsequent depressive symptoms(Time T) was not significant for: (a) the negative cognitive style composite score (path b: b = 0.07, SE = 0.06, t(911) = 1.16, p = 0.25) or (b) the weakest link (path b: b = 0.07, SE = 0.06, t(911) = 1.15, p = 0.25). Thus, neither mediation model was significant, which potentially suggests specificity for interpersonal as opposed to noninterpersonal stressors.

Self-Criticism and Dependency

Similar to the analyses described above, we also examined whether dependent interpersonal stress mediates the relationship between self-criticism and depressive symptoms. In the original model, gender, age, initial stress, and initial depressive symptoms were included as covariates. However, as the model would not converge, parameter constraints were relaxed. Specifically, baseline stress was not included in the model. The estimated model indicated that higher self-criticism is associated with higher levels of dependent interpersonal stress (path a: b = 5.6057, SE = 1.05, t(909) = 5.33, p < 0.0001). Additionally, when controlling for the proportion of variance accounted for by dependent interpersonal stress predicting depressive symptoms (path b: b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, t(909) = 3.72, p = 0.002), dependent interpersonal stress partially mediates the relationship between self-criticism and subsequent depressive symptoms (path c: b = 3.87, SE = 0.69, t(909) = 5.57, p < 0.0001). When examining the indirect effect, the 95% CI suggests that the mediation effect is significant (path a*bj: b = 0.61, SE = 0.20; 0.22, 1.01).

A mediation model with dependency as the independent variable was also estimated. An autoregressive covariance structure and random effects (i.e., random slope and intercept) were included in the model prior to estimation. Results indicate that dependency did not predict higher levels of dependent interpersonal stress (path a: b = 1.09, SE = 1.08, t(876) = 1.01, p = 0.31). As this path is a critical part of the mediation model, the full model was not tested.

Models including noninterpersonal stress were estimated in order to examine model specificity (i.e., dependent interpersonal versus noninterpersonal stress), and importantly, noninterpersonal stress did not predict changes in depressive symptoms in models including: (a) self-criticism (path b: b = 0.06, SE = 0.06, t(906) = 1.06, p = 0.29) or (b) dependency (path b: b = 0.06, SE = 0.06, t(876) = 1.00, p = 0.32).

Vulnerability Mediation Models: Predicting Above and Beyond

We next examined a mediation model that concurrently included negative cognitive style, weakest link and self-criticism. In line with our data analytic approach, we estimated a single simultaneous model. However, given the high correlation between the negative cognitive composite score and the weakest link, we estimated these effects in separate models: (a) self- criticism and negative style composite score and (b) self-criticism and weakest link. Of note, for models to converge, we did not control for baseline dependent interpersonal stress in the below models. Results of the model estimations suggest that self-criticism predicted above and beyond, which may indicate that self-criticism plays a particularly pernicious role within the stress generation framework. Specifically, for the model including negative cognitive style composite score and self-criticism (see Table 2), self-criticism predicts a greater level of dependent interpersonal stress. After controlling for the variance accounted for by the pathway linking dependent interpersonal stress(Time T-1) and depressive symptoms(Time T), dependent interpersonal stress(Time T-1) partially mediates the relationship between self-criticism and depressive symptoms(Time T). Importantly, review of the 95% CI results indicated that the mediation effect is significant (path a*bj: b = 0.39, SE = 0.17; 0.05, 0.72).

Table 2.

Time-Lagged Multilevel Model: An Examination of Negative Cognitive Composite Score versus Self-Criticism

| Predictor | Parameter Estimate (b) |

Standard Error |

t-Value | Degrees of Freedom (df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Interpersonal | ||||

| Stress(Time T-1): | ||||

| Age | −0.26 | 0.35 | −0.74 | 847 |

| Gender | 53.16 | 3.48 | 15.26*** | 847 |

| Negative Cognitive Composite | −0.54 | 2.83 | −0.19 | 847 |

| Self-Criticism | 5.66 | 2.84 | 1.99* | 847 |

| Depressive Symptoms(TimeT) Model: | 847 | |||

| Gender | 21.63 | 1.62 | 13.32*** | 847 |

| Initial Depressive Symptoms | 0.24 | 0.05 | 4.82*** | 847 |

| Dependent Interpersonal | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.30* | 847 |

| Stress (Time T-1) | ||||

| Negative Cognitive Composite | 0.25 | 1.14 | 0.22 | 847 |

| Self-Criticism | 2.31 | 1.16 | 1.99* | 847 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Similarly, when examining a model including both weakest link and self-criticism, self-criticism predicted above and beyond a weakest link approach (see Table 3). Specifically, self-criticism predicts a greater occurrence of dependent interpersonal stress. When accounting for the proportion of variance for dependent interpersonal stress(Time T-1) predicting depressive symptoms(Time T), such stress(Time T-1) partially mediates the relationship between self-criticism and depressive symptoms(Time T). We next examined the indirect effect, and the 95% CI results indicated that the mediation effect is significant (path a*bj: b = 0.34, SE = 0.11; 0.12, 0.55).

Table 3.

Time-Lagged Multilevel Model: An Examination of Weakest Link versus Self-Criticism

| Predictor | Parameter Estimate (b) |

Standard Error |

t-Value | Degrees of Freedom (df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Interpersonal | ||||

| Stress(Time T-1): | ||||

| Age | 3.31 | 0.12 | 28.69*** | 847 |

| Gender | 6.72 | 2.11 | 3.18** | 847 |

| Weakest Link Approach | 1.71 | 1.11 | 1.54 | 847 |

| Self-Criticism | 5.44 | 1.12 | 4.85*** | 847 |

| Depressive Symptoms(Time T) Model: | 847 | |||

| Gender | 4.92 | 1.25 | 3.93*** | 847 |

| Initial Depressive Symptoms | 0.30 | 0.05 | 5.76*** | 847 |

| Dependent Interpersonal | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.07* | 847 |

| Stress (Time T-1) | ||||

| Weakest Link Approach | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.27 | 847 |

| Self-Criticism | 2.24 | 0.68 | 3.28** | 847 |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

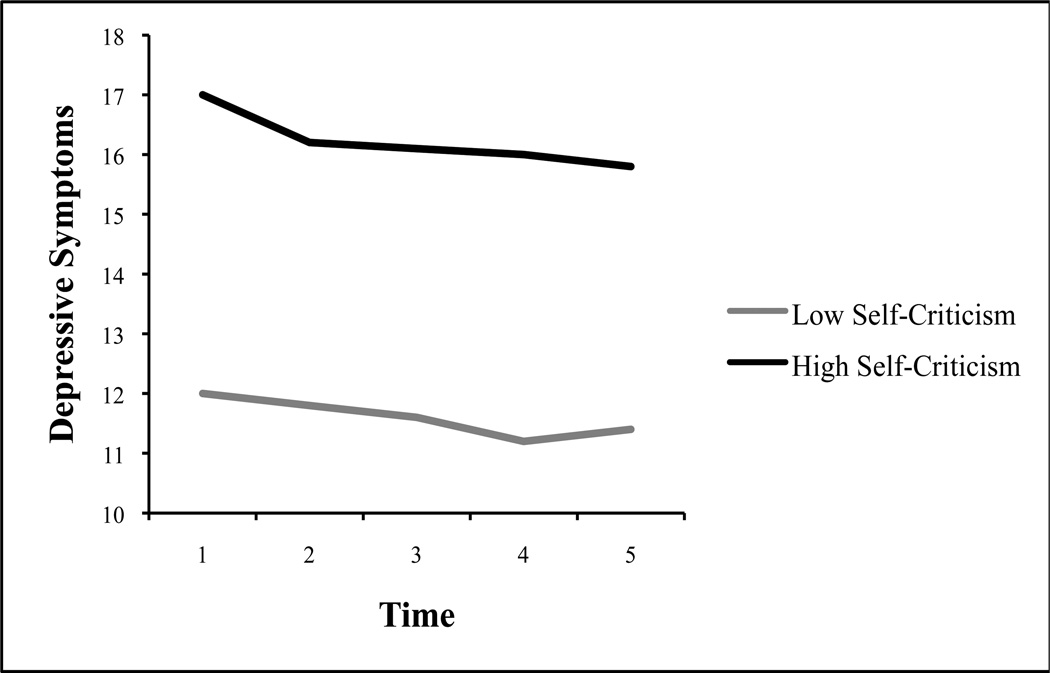

As the findings above underscore the importance of examining self-criticism, we used the fixed effects from our self-criticism mediation model in order to calculate predicted depressive symptoms for individuals with reported low versus high self-criticism (i.e., 1 SD above or below sample mean). By calculating the predicted estimates for depressive symptoms, the analyses examine the effect of dependent interpersonal stress in contributing to depressive symptoms at each assessment. In doing so, it provides a means of examining the predictive validity of our model. Results in Figure 2 suggest that adolescents reporting higher levels of self-criticism are more likely to report higher levels of depressive symptoms over time.

Figure 2.

Predicted Depressive Symptoms for Adolescents Reporting Low Versus High Self-Criticism

Note. Higher levels of the self-criticism denote greater cognitive vulnerability; CESD ≥ 16 accepted cutoff for clinically significant depressive symptoms.

An Exploration of Gender Differences

In order to examine whether the mediation models were stronger in girls versus boys, we examined whether gender moderated meditational pathways leading to dependent interpersonal stress and depressive symptoms. Importantly, the same data analytic outlined above was utilized; however, we explored whether gender moderated the pathway between: (a) the independent variable and mediator (i.e., dependent interpersonal stress) and (b) independent variable and dependent variable (i.e., depressive symptoms). Only significant mediation models were estimated. In contrast to our hypotheses, no gender differences emerged. First, a negative cognitive style composite approach did not interact with gender to predict significant changes in dependent interpersonal stress (path a: b = −1.28, SE = 1.27, t(911) = −1.01, p = .31) or depressive symptoms (path c: b = −0.08, SE = 0.89, t(911) = −0.08, p = .93). Second, gender did not moderate the pathway between the weakest link approach and: (a) dependent interpersonal stress (path a: b = −0.30, SE = 1.22, t(910) = −0.24, p = .81) or (b) depressive symptoms (path c: b = 1.04, SE = 0.90, t(910) = 1.15, p = .25). Last, when examining self-criticism, gender did not moderate the pathway between dependent interpersonal stress (path a: b = 2.46, SE = 1.31, t(906) = 1.88, p = .06) or depressive symptoms (path c: b = 1.47, SE = 0.79, t(906) = 1.85, p = .07).

Discussion

The current study examined whether cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability factors predict the occurrence of dependent interpersonal, but not noninterpersonal stressors, which in turn, led to the manifestation of depressive symptoms over time. Assessments were conducted during a 6-month period using a multi-wave, longitudinal design, and while results implicated both depressogenic attributional styles (i.e., composite score and weakest link approach) and self-criticism, concurrent model estimations suggest that self-criticism may play a particularly pernicious role in leading to stress and depressive symptoms over time. In contrast to our hypothesis and consistent with Shih and colleagues (2009), dependency did not predict dependent interpersonal stressors, underscoring the critical need to tease apart interpersonal and noninterpersonal stressors when examining vulnerability to depression in youth (see Shahar & Priel, 2003). Surprisingly, idiographic, time-lagged models did not reveal gender differences. As a whole, the findings address an important theoretical and empirical gap in the adolescent depression literature.

In our first set of analyses, we examined whether a composite negative cognitive style and/or weakest link approach predicted stress and subsequent depressive symptoms. Independent multilevel models including either the composite or the weakest link approach found that higher levels of cognitive vulnerability contributed to a greater occurrence of dependent interpersonal but not noninterpersonal stressors. Further, higher levels of dependent interpersonal stressors mediated the relationship between depressogenic attributional styles (i.e., composite and weakest link) and depressive symptoms. Given the robust association between the composite and weakest link score, a direct comparison of the two approaches was not conducted. Nevertheless, a closer examination of the weakest link may shed important light on the role of depressogenic attributional styles in these action-oriented models. In particular, 68% of adolescents endorsed the global-stable dimension (i.e., cause) as their most vulnerable cognitive style. This has two important implications. First, negative cognitive styles are hypothesized to crystallize in early adolescence (see Gibb et al., 2006), and these findings may suggest that a depressogenic attributional style ascribing negative events as global and stable may be the more prominent negative cognitive style to emerge. Second, and directly related, it would seem that a global-stable dimension (versus depressogenic cognitive styles regarding consequences − 10% or self – 22%) may be driving the effect for the weakest link approach as well as the negative cognitive style composite score approach. Taken together, the global-stable negative cognitive style appears to be critically implicated in leading to stress and depression, and consequently, warrants additional exploration in future research. Overall, whether using a composite or weakest link approach, depressogenic cognitive vulnerabilities appear to continuously influence one’s perceptions, expectations, and responses to interpersonal relationships and thereby, increase susceptibility to depression.

In contrast to our hypothesis, results indicate that dependency does not exert a significant impact on stress and depressive symptoms over time. These findings are surprising in light of research suggesting that adolescence is a period defined by a greater investment in interpersonal relationships, particularly in the peer domain (Rudolph, 2008), and further, other interpersonal vulnerability factors, including social support deficits and excessive reassurance seeking, have been implicated in triggering interpersonal stress and depression in youth (Auerbach, Bigda-Peyton, Eberhart, Webb, & Ho, 2011; Shih et al., 2009). Notably, Auerbach et al. (2011) assert that adolescents reporting social support deficits, especially in parent and classmate domains, are more likely to experience a greater occurrence of interpersonal stressors, which over time, leads to the developmental unfolding of depressive symptoms. Similarly, Shih and colleagues (2009) report that excessive reassurance seeking predicts higher levels of dependent interpersonal stress at a 1-year follow-up assessment. Taken together, these findings posit that interpersonal vulnerability factors play a prominent role in contributing to interpersonal stressors; however, similar to Shih and colleagues’ (2009) findings in children, dependency does not contribute to interpersonal stress among adolescents. One possibility for our null findings may be that it has been hypothesized that dependency includes both maladaptive and adaptive subcomponents (see Shahar, 2008). Whereas the maladaptive component is associated with a fear of abandonment and helplessness, the adaptive component seems to tap into interpersonal relatedness. Shahar asserts that the maladaptive component, which he qualifies as “undifferentiated dependence on others” (p. 61), is associated with psychopathology and associated problems while relatedness is strongly predictive of adaptive processes. In the current study, our measure of dependency does not allow us to meaningfully discriminate the adaptive and maladaptive subcomponents. Nevertheless, future research would benefit from utilizing a more fine-grained assessment of dependency in order to disentangle its role in the stress generation process.

Self-Criticism and Adolescent Depression

We found that self-criticism prospectively predicts dependent interpersonal stressors, and subsequent depressive symptoms over time. Moreover, the effect is specific to dependent interpersonal stressors as opposed to noninterpersonal stressors. When concurrently estimated within the same model as negative cognitive style (i.e., separate models including composite score or weakest link), self-criticism also predicts above and beyond suggesting that it may play a central role in adolescent depression. One explanation for the robust impact of self-criticism is Shahar and Henrich’s (2013) Axis of Criticism Model, which asserts that self-criticism degrades an adolescent’s self-identity, relationships, and social systems. Coupled with critical expressed emotions within the social support system, an adolescent is left devoid of compensatory social support, and for many, the vulnerability tandem leads to the development of depressive symptoms and episodes. To date, no study has examined the Axis of Criticism Model, however, preliminary research supports the basic tenets of this promising conceptualization (see Wedig & Nock, 2007). Nevertheless, future research is warranted to examine whether expressed emotion moderates the relationship between stress and self-criticism, or alternatively, whether, it directly moderates the pathway between self-criticism and depressive symptoms.

Limitations

There are several strengths in the current study including the concurrent estimation of multiple vulnerability factors among an adolescent sample, the prospective, multi-wave design, and the sophisticated data analytic approach. It is also important, however, to highlight limitations of the current research. First, the present study assesses self-report depressive symptoms to examine the temporal unfolding and fluctuations of symptoms over time. Nevertheless, employing a clinical interview would determine whether proposed models predict clinically significant depressive episodes, which would be a benefit for future research. Second, stress generation research commonly employs the use of life event interviews to better delineate dependent versus independent events, interpersonal versus noninterpersonal stressors, and acute versus chronic stress (for a review, see Hammen, 2005). The current study utilized a negative event checklist. While such an approach has been used in prior research (Auerbach et al., 2010), there are important concerns that one must consider about the use of a Likert scale, which operationalizes stress as always to never. Thus, utilization of stress interviews is certainly the gold standard. Third, self-report instruments are subject to inherent reporter biases, and for this reason, it is also helpful to include third-party measurement and observational coding. Fourth, we utilized the self-report instruments commonly used to assess cognitive vulnerability in youth; however, it is important to note that in the current study, the Cronbach’s alphas for some of these measures were in the low to moderate range (self-criticism − .57; dependency − .68). While the internal consistency found for self-criticism and dependency is consistent with past use of this instrument (e.g., Abela, Sakellaropoulo, & Taxel, 2007), it may, unfortunately, influence the reliability of our findings. Relative to the Adolescent Cognitive Style Questionnaire, the self-criticism subscale within the Children’s Depressive Experiences Questionnaire contains fewer items, which may account, in part, for its modest internal consistency. Last, data was collected from a sample of adolescents from a middle-income area within an urban community. Adolescent participants were not directly questioned regarding information about their socioeconomic status as it is not clear that adolescents can accurately provide such information. Additionally, while all students were invited to participate, reasons for non-participation were not assessed. Importantly, both issues may have an unintended impact on the generalizability of our findings.

Clinical Implications

The current results suggest that in comparison to depressogenic attributional styles and dependency, self-criticism plays a particularly pernicious role in potentiating interpersonal stress and increasing risk for depression. Although self-criticism is often targeted in the context of cognitive behavioral therapy, these findings suggest that greater attention may be warranted; especially in determining how self-criticism shapes an adolescent’s interpersonal experience.

Acknowledgments

Partial support was provided by the: McGill University Social Sciences and Humanities Student Research Grant, Tommy Fuss Fund, and Kaplen Fellowship on Depression awarded through Harvard Medical School.

References

- Abela JRZ. The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:241–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1010333815728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, D'Alessandro DU. Beck's cognitive theory of depression: A test of the diathesis-stress and causal mediation components. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:111–128. doi: 10.1348/014466502163912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Sakellaropoulo M, Taxel E. Integrating two subtypes of depression: Psychodynamic theory and its relation to hopelessness depression in schoolchildren. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Taylor G. Specific vulnerability to depressive mood reactions in schoolchildren: the moderating role of self-esteem. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:408–418. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 35–78. [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Sarin S. Cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression: A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Adams P, Abela JR, Auerbach R, Skitch S. Self-criticism, dependency, and stress reactivity: an experience sampling approach to testing Blatt and Zuroff's (1992) theory of personality predispositions to depression in high-risk youth. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:1440–1451. doi: 10.1177/0146167209343811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Liu RT, Bender RE. Stress generation research in depression: A commentary. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3:380–388. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Bigda-Peyton JS, Eberhart NK, Webb CA, Ho M-HR. Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:475–487. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Eberhart NK, Abela JR. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in Canadian and Chinese adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:57–68. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach RP, Ho MH. A cognitive-interpersonal model of adolescent depression: the impact of family conflict and depressogenic cognitive styles. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:792–802. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.727760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Preacher KJ, Gil KM. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:142–163. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In: Clayton PJ, Barrett JE, editors. Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches. New York: Raven; 1983. pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Blankstein KR, Dunkley DM. Evaluative concerns, self-critical, and personal standards perfectionism: A structural equation modeling strategy. In: Flett GL, Hewitt PL, editors. Perfectionism: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, D'Afflitti JP, Quinlan DM. Experiences of depression in normal young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:383–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: Two prototypes for depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12:527–562. [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Clara IP, Enns MW. Self-criticism, maladaptive perfectionism, and depression symptoms in a community sample: A longitudinal test of the mediating effects of person-dependent stressful life events. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;23:336–349. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, Zuroff DC, Blankstein KR. Self-critical perfectionism and daily affect: Dispositional and situational influences on stress and coping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:234–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley DM, Zuroff DC, Blankstein KR. Specific perfectionism components versus self-criticism in predicting maladjustment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:665–676. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Walshaw PD, Comer JS, Shen GHC, Villari AG. Predictors of attributional style change in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:425–439. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greden JF. The burden of recurrent depression: Causes, consequences, and future prospects. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Gibb BE, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hankin BL, Swendsen JD. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the cognitive style questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:824–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity, and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent. 2002;31:491–504. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Siler M. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in adolescence. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:607–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Oppenheimer C, Jenness J, Barrocas A, Shapero BG, Goldband J. Developmental origins of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: Review of processes contributing to stability and change across time. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1327–1338. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Stewart JG. Symptom specificity and the prospective generation of life events in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:278–287. doi: 10.1037/a0015749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Wingate LR, Otamendi A. An interpersonal addendum to the hopelessness theory of depression: Hopelessness as a stress and depression generator. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24:649–664. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Knight E. The epidemiology of depression in adolescents. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of Depression in Adolescents. New York, NY US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Priel B, Shahar G. Dependency, self-criticism, social context and distress: Comparing moderating and mediating models. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;28:515–525. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly LC, Ciesla JA, Felton JW, Weitlauf AS, Anderson NL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression: a comparison of the weakest link, keystone and additive models. Cognition & Emotion. 2012;26:521–533. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.595776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Developmental influences on interpersonal stress generation in depressed youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:673–679. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Crossfield AG. Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G. What measure of interpersonal dependency predicts changes in social support? Journal of Personality Assessment. 2008;90(1):61–55. doi: 10.1080/00223890701693751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Henrich CC. Axis of Criticism Model (ACRIM): An integrative conceptualization of person-context exchanges in vulnerability to adolescent psychopathology. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Joiner TE, Jr, Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. Personality, interpersonal behavior, and depression: Co-existence of stress-specific moderating and mediating effects. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36:1583–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Priel B. Active vulnerability, adolescent distress, and the mediating/suppressing role of life events. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Abela JR, Starrs C. Cognitive and interpersonal predictors of stress generation in children of affectively ill parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9267-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Eberhart NK. Gender differences in the associations between interpersonal behaviors and stress generation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wedig MM, Nock MK. Parental expressed emotion and adolescent self-injury. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1171–1178. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e3180ca9aaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Moskowitz DS, Cote S. Dependency, self-criticism, interpersonal behaviour and affect: evolutionary perspectives. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:231–250. doi: 10.1348/014466599162827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]