Abstract

Background

Imaging patterns of benign proliferative processes often complicate the assessment of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We investigated the pathologic and biologic characteristics of false positive enhancement by breast MRI.

Methods

DCIS (n = 45), benign (n = 5), and false-positive (MRI enhancement and nonmalignant pathology) (n = 10) cases were characterized by immunohistochemistry and MRI features.

Results

For DCIS cases, images that overestimated pathologic size had heterogeneous enhancement on MR, were estrogen receptor positive, and were low grade by pathology. False-positives had higher rates of proliferation, angiogenesis, and inflammation compared with benign tissue but lower values than DCIS. Benign proliferative processes accounted for all false-positive and size overestimated cases.

Conclusions

Lesions that enhance on MRI have higher proliferation, angiogenesis, and inflammation compared with nonproliferative breast tissue. Benign proliferative processes often enhance on MRI and are difficult to differentiate from low-grade, ER+ DCIS lesions. False-positive MRI enhancement may reflect a spectrum of change within high-risk tissue.

Keywords: Breast carcinoma in situ, Magnetic resonance imaging, Benign breast disease

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) holds significant potential as a noninvasive tool to characterize ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) [1–3]. As our understanding of invasive breast cancer has progressed, we have learned that it is a heterogeneous disease, encompassing different phenotypic categories that arise from a range of biological processes [4]. DCIS, a preinvasive cancer, is a variable disease as well. We have used MRI to show differences in size and extent of both invasive and noninvasive tumors and their response to interventions in the neoadjuvant setting [5,6]. Surgical and innovative treatment approaches would benefit tremendously from a tool that can reliably capture the size and extent of DCIS and reflect the underlying pathology. MRI may enable neoadjuvant interventions in the DCIS setting and accelerate our ability to tailor treatment and prevention to the underlying biology. One barrier to the use of MRI in the setting of DCIS is the common finding of progressive or plateau enhancement that turns out to be “false” positive [7]. We asked whether the enhancement had biological significance and therefore investigated the pathologic and biologic characteristics of benign proliferative processes that complicate detection of DCIS by MRI.

Our goals were (1) to determine if there are subtypes of DCIS where MRI size estimation is relatively more or less accurate and (2) to identify pathologic features of lesions that enhance but do not represent DCIS or invasive cancer.

Methods

Between 1994 and 2002, 100 patients diagnosed with DCIS agreed to undergo MRI before surgery. Patients underwent segmental resection (image guided) or mastectomy based on the extent of their disease and personal preference for surgical intervention. Of these, 45 patients had both electronically archived images for review as well as sufficient tissue on which to perform biomarker studies. Cases from these 45 patients with biopsy-proven DCIS who underwent MRI were characterized by pathology (nuclear grade, presence of comedo necrosis, size, and density of disease) and immunohistochemistry (proliferation [Ki67], angiogenesis [CD34], and inflammation [CD68]) and MRI features (enhancement patterns, distribution, size, and density). Pathologic size of DCIS was based on the number of contiguous sections that contained disease or the largest diameter on a single given slide, whichever was larger. These were compared with 5 samples of benign breast tissue (sampled from a quadrant of a mastectomy specimen in an enrolled study patient that did not enhance on MRI). Ten false-positive cases were identified from patients who had surgical excisional biopsies on the basis of MRI findings. These excisions were guided by ultrasound (n = 2), mammography (n = 2), MRI (n = 3), palpation (n = 2, including 1 ductal papilloma found on duct exploration), or identified from prophylactic mastectomy specimen (n = 1). These cases were chosen for analysis because there was a clear imaging or palpable correlate of the MRI lesion in question, but the final surgical specimen pathology was not found to be malignant. Evaluation of the false-positive cases was conducted by a team consisting of radiologists, surgeons, and pathologists to determine which pathologic block was the most appropriate to section and stain. Pair-wise correlations between MRI-derived and standard pathological variables were calculated by using both Pearson and Spearman rank correlation coefficients and were tested for statistical significance using Fisher’s logarithmic transformation. Benign pathological findings were stratified into 3 categories of low, medium, and high risk according to the criteria established by Hartmann et al [8].

Results

Among the 45 cases with DCIS confirmed by final pathology, many more cases had an overestimation of the size of DCIS than an underestimation. MRI overestimated size of malignancy by 2-fold in 13 cases, but there were only 3 cases in which MRI underestimated size of malignancy by more than half.

For DCIS cases, histopathology and immunohistochemistry variables correlated with MRI features (r = 0.73). The correlation was most strongly driven by size; density of pixels on MRI; compactness of ducts on pathology; and CD68, a macrophage marker (P < .05) [9].

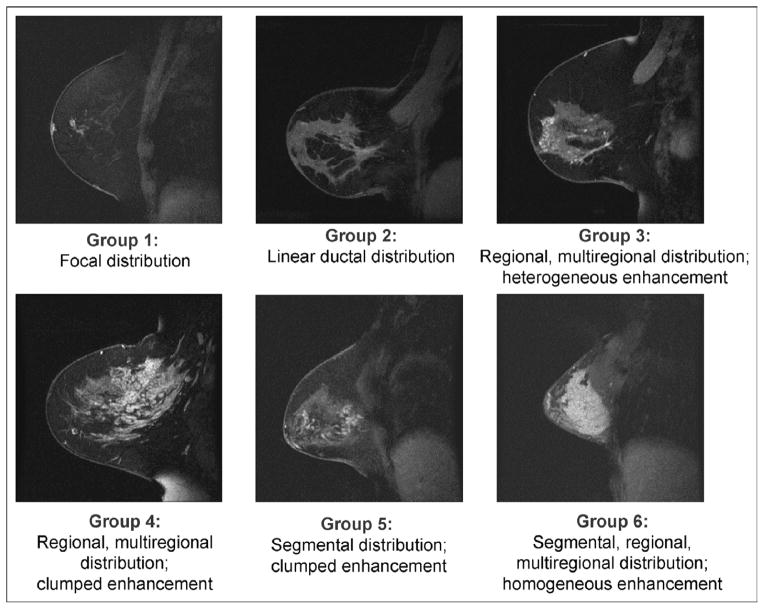

The MR Birads lexicon terms for enhancement (reflecting density) and distribution (representing size and extent) were combined to describe 6 groups of DCIS lesions: (1) focal, (2) linear ductal, (3) regional heterogeneous, (4) regional clumped, (5) segmental clumped, and (6) homogeneous [10] (Fig 1).

Fig. 1.

American College of Radiology MRI Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BIRADS) lexicon terms for enhancement and distribution were combined to describe 6 groups of DCIS lesions: (1) focal, (2) linear ductal, (3) regional heterogeneous, (4) regional clumped, (5) segmental clumped, and (6) homogeneous.

Where MRI overestimates DCIS

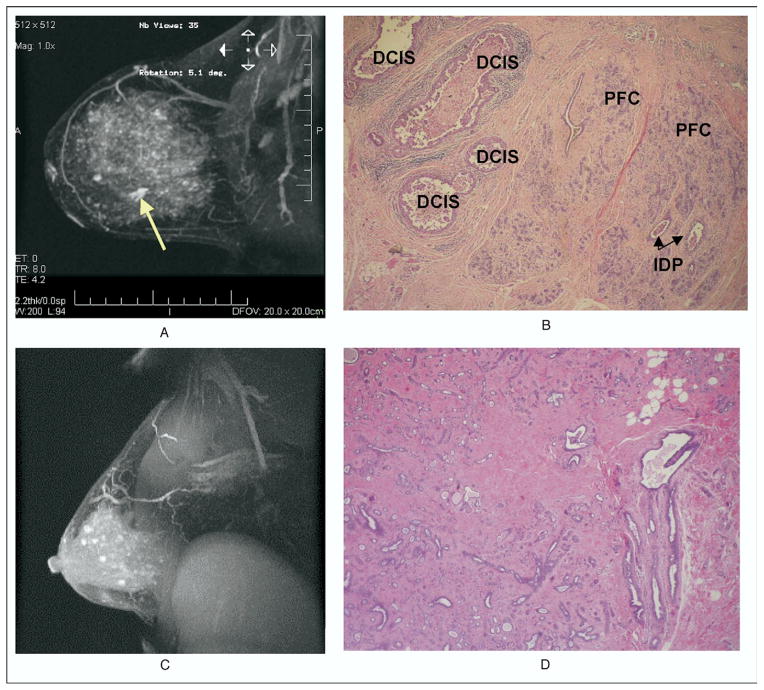

Significant discrepancies in MRI and pathology size estimates provided the opportunity to evaluate rare cases in which MR size was <50% of pathology size (n = 3) and those cases (n = 13) in which MRI size is ≥200% of pathology size. DCIS was identified in all of these cases. MRI types where DCIS size was ≥200% of pathology size were predominantly groups 3 and 4 (P < .05). These lesions were mostly ER positive, noncomedo, and non–high grade. A signal was usually seen scattered throughout the parenchyma of the breast, but there was difficulty assessing the true margins of the lesion (Fig. 2A and B). Surrounding benign processes were 90% Hartmann’s intermediate to high risk (n = 8 for intermediate [60%] and n = 4 for high [30%]).

Fig. 2.

(A) MRI showing a 7.7-cm area of enhancement, whereas histologic sections revealed DCIS totaling only 1.5 cm surrounded by benign proliferative process (B). Careful evaluation of the MRI (A) showed a 1.5-cm lesion (yellow arrow), surrounded by 7.7 cm of enhancement. (C) MRI enhancement of the right breast in a 46-year-old woman with extensive contralateral DCIS. The corresponding pathology showed only sclerosing adenosis (D). There was no evidence of malignancy. PFC = proliferative fibrocystic changes; IDP = intraductal papilloma.

Biology of false-positive MRI enhancement

In cases in which MRI showed enhancement but no DCIS malignancy (in situ or invasive) was found (n = 10), we examined the tissue and performed immunohistochemical analysis. One hundred percent showed benign proliferative processes (sclerosing adenosis, intraductal papilloma, proliferative fibrocystic changes, and atypical or florid ductal hyperplasia) (Fig. 2C and D). The false-positive cases were categorized by the Hartmann risk criteria [8]. Nonproliferative fibrocystic changes have the lowest 15-year risk of malignant transformation (relative risk [RR] = 1.27), proliferative fibrocystic changes without atypia have an intermediate risk (RR = 1.88), and proliferative fibrocystic changes with atypia have the highest risk (RR = 4.24). Of the false-positive MRI cases in our study, 80% had benign lesions with an intermediate to high risk (n = 7 for proliferative fibrocystic changes without atypia and n = 1 for proliferative fibro-cystic changes with atypia). False-positive MRI lesions had significantly higher proliferative, angiogenic, and inflammatory patterns than benign tissue but lower values than DCIS (P < .05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean values of immunohistochemical biomarkers and lesion size by cohort

| Tissue type | n | Proliferation (% cells staining Ki67) | Inflammation (% cells staining CD68) | Angiogenesis (% cells staining CD34) | Size by MRI (mm) | Size by pathology (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 5 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 12.9 | NA | NA |

| False positive | 10 | 12.8 | 15.8 | 44.8 | 30.1 | NA |

| DCIS in which MRI size ≥200% pathology size | 13 | 22.2 | 25.6 | 57.2 | 55.7 | 13.8 |

| DCIS in which MRI size <50% pathology size | 3 | 18.8 | 29.3 | 63.3 | 25.7 | 64 |

| Remaining DCIS cases | 29 | 30.3 | 54.3 | 71.1 | 46.2 | 37.5 |

NA = not applicable.

Comments

Although DCIS has a varied presentation by MRI, pathology and imaging variables are significantly correlated, suggesting that MRI provides insight into the type of DCIS pathology in the breast. Groups 3 and 4, the non–high-grade ER-positive DCIS lesions, are recognizable by MRI. These DCIS lesions are frequently accompanied by areas of enhancement on MRI that are difficult to distingish from the DCIS itself and reflect moderate to high-risk benign proliferative processes. This may reflect a spectrum of high-risk changes in breast tissue in women who develop non–high-grade ER-positive DCIS.

Proliferative lesions are often seen in the setting of progressive contrast enhancement on MRI. Thus, 1 strategy for improving diagnostic accurate assessment of the extent of DCIS might be to use high-resolution MRI in combination with the signal enhancement ratio or some other type of kinetic analysis to assess the background parenchyma [11]. These studies are in progress.

We have previously published on the sensitivity and specificity of size correlation among mammography, MRI, and pathology [12]. In our study, MRI estimates of size are surprisingly well correlated with those based on pathologic examination, given the very different methods for size estimation of each technique. Size based on pathologic examination is difficult to measure because the disease is 3-dimensional and histology sections are 2-dimensional. Thus, the actual size is an estimate based on how many tissue sections are submitted, their thickness, and the presence of DCIS in consecutive sections. MRI gives a 3-dimensional representation and therefore holds some advantage over mammography [1,12]. However, MRI is also prone to error because DCIS is often found in the setting of benign proliferative lesions, such as sclerosing adenosis, atypia, and proliferative fibrocystic change [7], which also enhance on MRI. Thus, where DCIS ends and proliferative changes begin can be difficult to determine. MRI consistently and accurately reflects pathologic size, except in the presence of proliferative changes that appear to be more common in ER-positive noncomedo lesions (MRI groups 3 and 4) [9].

Benign proliferative lesions, when identified by MRI, show increased proliferation and angiogenesis. We found that MRI enhancement does reflect underlying biologic changes, and, in fact, all of the false-positive MRI cases showed moderate- to high-risk proliferative fibrocystic changes. Such proliferative changes have been associated with a significant increase in the risk of malignant transformation compared with normal breast epithelium [8]. When MRI enhancement overestimated the size of DCIS, usually in the setting of ER-postive non–high-grade DCIS, we also found moderate- and high-risk proliferative changes. Our findings suggest that ER-positive DCIS with diffuse enhancement represents a spectrum of surrounding high-risk lesions that may be amenable to risk reduction with hormonal therapy. We are currently studying the impact of 3 months of neoadjuvant hormone therapy and, in a separate trial, 3 to 6 weeks of preoperative statin treatment in nearly 80 women with DCIS [13]. We are in the process of prospectively analyzing which MRI groups are associated with the best responses to these interventions.

Conclusion

This study represents an important step forward in refining MRI as a noninvasive tool in the assessment of DCIS and understanding the biologic basis for enhancement when cancer is not present.

Footnotes

Presented at the 7th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Breast Surgeons, Baltimore, Maryland, April 5–9, 2006

References

- 1.Bartella L, Liberman L, Morris EA, Dershaw DD. Nonpalpable mammographically occult invasive breast cancers detected by MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:865–70. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung A, Saouaf R, Scharre K, Phillips E. The impact of MRI on the treatment of DCIS. Am Surg. 2005;71:705–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groves AM, Warren RM, Godward S, Rajan PS. Characterization of pure high-grade DCIS on magnetic resonance imaging using the evolving breast MR lexicon terminology: can it be differentiated from pure invasive disease? Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23:733–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabrielson E, Argani P. Heterogeneity in the pathology and molecular biology of breast cancer. Curr Genome. 2002;3:477–88. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esserman L, Hylton N, Yassa L, et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of breast cancer: evidence for improved preoperative staging. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:110–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Partridge SC, Gibbs JE, Lu Y, et al. MRI measurements of breast tumor volume predict response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and recurrence-free survival. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1774–81. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.6.01841774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kneeshaw PJ, Lowry M, Manton D, et al. Differentiation of benign from malignant breast disease associated with screening detected microcalcifications using dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Breast. 2006;15:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:229–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esserman L, Kumar AS, Herrera AF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging captures the biology of ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2006 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5518. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lesion Diagnosis Working Group of the International Working Group on Breast MRI. Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System—Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACR BI-RADS—MRI: American College of Radiology; 2004. pp. 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esserman L, Hylton N, George T, Weidner N. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to assess tumor histopathology and angiogenesis in breast carcinoma. Breast J. 1999;5:13–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.1999.005001013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang ES, Kinkel K, Esserman LJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients diagnosed with ductal carcinoma-in-situ: value in the diagnosis of residual disease, occult invasion, and multicentricity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:381–8. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang ES, Esserman L. Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ: trial design and preliminary results. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(suppl):37S–43. doi: 10.1007/BF02524794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]