Abstract

A quantitative measure of three-dimensional breast density derived from noncontrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was investigated in 35 women at high-risk for breast cancer. A semiautomatic segmentation tool was used to quantify the total volume of the breast and to separate volumes of fibroglandular and adipose tissue in noncontrast MRI data. The MRI density measure was defined as the ratio of breast fibroglandular volume over total volume of the breast. The overall correlation between MRI and mammographic density measures was R2=.67. However the MRI/mammography density correlation was higher in patients with lower breast density (R2=.73) than in patients with higher breast density (R2=.26). Women with mammographic density higher than 25% exhibited very different magnetic resonance density measures spread over a broad range of values. These results suggest that MRI may provide a volumetric measure more representative of breast composition than mammography, particularly in groups of women with dense breasts. Magnetic resonance imaging density could potentially be quantified and used for a better assessment of breast cancer risk in these populations.

Keywords: Volumetric breast density, Breast MRI, Fuzzy c-means, Segmentation, Breast cancer risk, Mammographic density, MR breast density

1. Introduction

Mammographic breast density is recognized as a strong marker of breast cancer risk [1–3]. “Mammographic density” is defined as the proportion of radiodense fibroglandular tissue in the breast [4]. Women with high breast density have a two- to sixfold increased risk of developing breast cancer than women with fatty breasts [1]. Mammography is the common modality to quantify breast density and screen for breast cancer, but its sensitivity in detecting breast cancer decreases when breast tissue is dense, which is the case for 40% to 50% of women under 50 years [5]. Kolb et al. [6] also showed that mammography sensitivity to detect breast cancer decreased from 98% in fatty breasts with less than 25% apparent mammographic density to 42% in women with over 75% mammographic density. This is of particular concern for populations at high risk of breast cancer whose breast cancer risk screening should be started earlier than the general population [7] and whose breast density may be difficult to assess using mammography.

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides high soft-tissue contrast and allows the three-dimensional characterization of breast composition. This modality is used increasingly as part of breast cancer management worldwide [8]. Recently, MRI was used to quantify tissue composition in healthy volunteers [9]. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging has been shown to differentiate fibroglandular from adipose tissue with high precision [10,11]. In reference [12], we presented a semiautomated technique, allowing a robust segmentation of fibroglandular tissue volume, to quantify a ratio of fibroglandular tissue and total breast volume (“MR density”) from MRI data.

Since there is a direct relationship between breast density and breast cancer risk, we wanted to assess differences between the measures of two-dimensional (2-D) mammo-graphic density and three-dimensional (3-D) MR density in a cohort of high-risk women.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed MRI data of 35 high-risk women who had been recruited at our institution and for whom both MRI and mammographic films were available. Volumetric MR density was compared with mammographic density for each patient. The long-term goal of our research is to study the use of noncontrast MRI data to measure volumetric breast density and provide a much-needed reliable measure of breast cancer risk, to potentially help manage breast risk assessment of many younger or high-risk women who cannot benefit from mammographic information due to their high breast density.

2. Methodology

Between 2000 and 2006, 35 patients enrolled in high-risk screening protocols and received mammograms and breast MRI examinations at our institution. An institutional review board approved our study protocol, and all subjects gave informed consent. The patients’ ages ranged from 28 to 59 years, with mean age of 43 years. Mammographic films of all volunteers were available and were digitized to allow quantification of breast density with semiautomated software [13].

The inclusion criteria for high-risk protocols included a strong family history and/or high breast density as assessed by mammography and no cancer present in any breast. All women underwent a bilateral contrast-enhanced MRI scan as part of their research trials. Images were acquired on a 1.5-T Signa scanner (GE Healthcare) using a dedicated bilateral phased array breast coil. A fat-suppressed 3-D fast gradient-recalled echo sequence was used (TR/TE, 8/4.2; flip angle 20°; two repetitions.) [14]. The bilateral scans involved 60 slices, each 2-mm thick, acquired in the axial orientation resulting in a voxel size of 0.781×0.781×2 mm3.

Mammographic density was quantified from craniocaudal mammographic films. All films were digitized using a Vidar Herndon VA Diagnostic Pro Plus digitizer at 169-μm resolution and 16-bit dynamic range. The mammographic density was defined using the expert reading method, first described by Wolfe et al., and custom developed at our institution. The reading software was developed using Matlab computing language (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The digitized films were displayed on a high-resolution radiographic monitor, and the reader, a physician trained and certified in breast density assessment, manually delineated the radiodense areas representing fibroglandular tissue. The percentage area of dense tissue in the breast was determined by dividing the number of pixels outlined in the dense region by the total area of the breast as calculated by the computer software.

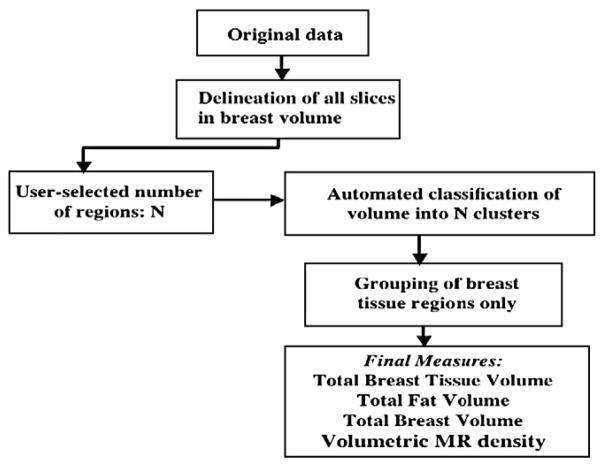

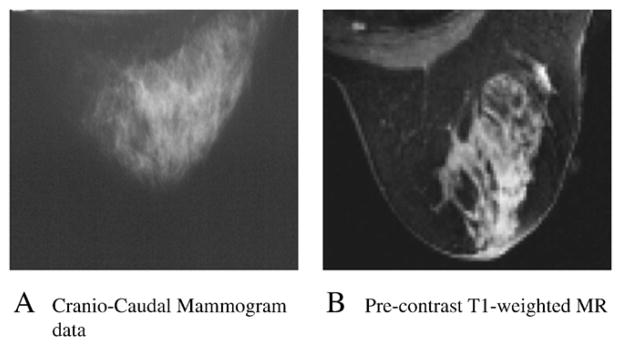

Precontrast MRI data were used to quantify the volume of fibroglandular tissue in the breast. Fig. 1 shows T1-weighted precontrast breast MRI data in which fibroglandular tissue is clearly visible (high intensities) surrounded by adipose tissue (low intensities) in the breast. Different types of fibroglandular tissue patterns are displayed in Fig. 1 and are representative of low (Fig. 1A) to high (Fig. 1D) MR density, respectively. By analogy to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) 1 to 4 classification of mammographic density [15], the four MR density groups present in Fig. 1 show fatty, scattered, heterogeneously dense and dense breast tissue.

Fig. 1.

Different breast tissue composition, low to high MR density.

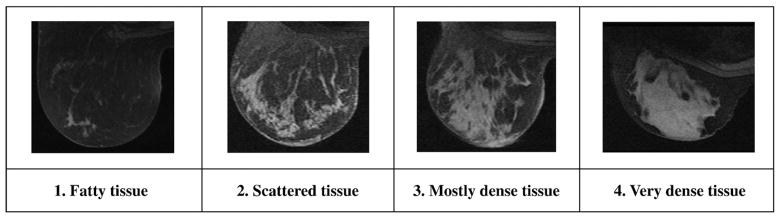

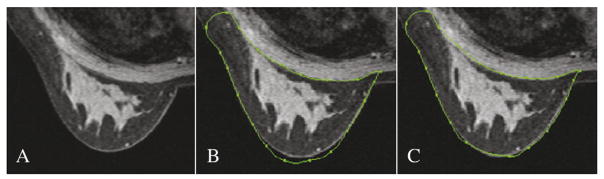

Our semiautomatic segmentation technique extracting three-dimensional regions of breast fibroglandular and adipose tissue from noncontrast MRI data has been described previously [12]. A summary of the segmentation steps is shown in Fig. 2. A graphical user interface was developed to interactively delineate regions around the breast under study. User-defined regions were extracted with a combination of Bezier splines and a Laplacian of Gaussian filter [16]. To facilitate the delineation of regions and reduce user interaction, a user may place or copy control points of Bezier splines close to the edges of the region of interest (Fig. 3B). The final contour is displayed after automatic attachment of the Bezier spline control points to the closest edges (Fig. 3C). Points that do not reach the desired final position are manually adjusted by the user to get a final appropriate contour. Typically, in most MRI breast volumes, since the shape of the breast does not change substantially between contiguous slices in axial data, contours are drawn every four to six slices depending on anatomy and on the quality of MRI data. Due to multiple differences in anatomy and MRI data homogeneity among patients, user interaction is necessary to edit contours to avoid the inclusion of parts of the chest wall or other regions in the breast volume. Anatomical rules were imposed to introduce similar total breast volume delineation in MRI data of all high-risk women, especially in the axilla and in the sternum regions.

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance density segmentation steps.

Fig. 3.

Original axial semiautomated delineation of the breast contour.

This technique was applied to axial MRI data of our high-risk cohort and the delineation of breast contours was performed on multiple MRI slices in order to obtain the total volume of the breast for each patient. Once the entire breast volume is delineated, and before the segmentation into regions of different tissue can be automatically performed, the user defines the number of different tissues or regions (N) to extract within the breast. Noncontrast T1-weighted breast MRI volumes generally exhibit two main regions (adipose and fibroglandular tissue); however, it is also necessary to define additional regions when (1) breast lesions may be visible (cysts, recognized by their round shapes and/or regions of different intensity within the fibroglandular tissue); (2) when the intensity of fibroglandular tissue in the MRI data is not uniform (variations of intensity levels often occur among large regions of breast tissue); or (3) when artifacts due to coil or MRI reconstruction are present.

Therefore, for each individual breast under study, the user must define the N regions, depending on the MRI volume and its content. The segmentation step then automatically classifies the whole breast volume into N breast tissue groups.

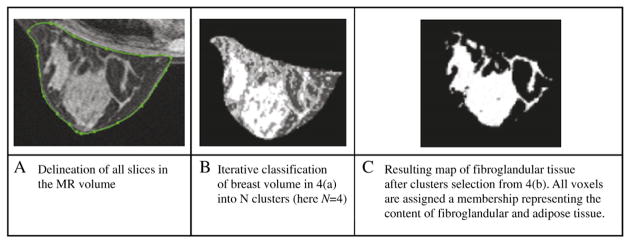

The automated iterative segmentation method is based on a soft fuzzy c-means technique [17–19] that labels MRI data depending on their “adipose” and “fibroglandular” tissue content within the entire breast. The unsupervised algorithm assigns a membership (percentage of fibroglandular tissue) to each voxel that translates the partial volume effects in the image. Partial volume effects happen when multiple tissues (adipose/fibroglandular tissue) contribute to a single voxel, making it difficult to classify these voxels into any of the tissue groups, in particular, around the edges. Assigned membership values are between 1 and 0, with 1 for voxels containing fibroglandular tissue only and 0 for those with adipose tissue only. Voxels with memberships between 0 and 1 carry a percentage of adipose tissue as well as a percentage of fibroglandular tissue. Since our technique allows voxels to contain both a percentage of fibroglandular and adipose tissue, in the final segmentation step, only the percentage of fibroglandular present in each voxel is accounted for in order to measure the total fibroglandular tissue volume in the breast. Our technique, therefore, allows the segmentation of MRI data into membership values without requesting user interaction for the choice of a threshold. This eliminates subjective user-dependent decisions in the segmentation process. As shown in Fig. 4, once the N groups have been segmented within the breast volume (Fig. 4B), the user can select and regroup Nft regions that belong to the “fibroglandular tissue” clusters only. The technique then automatically calculates the total volume of fibroglandular tissue in the Nft selected regions, adding all voxels’ fibroglandular tissue memberships together. The final segmentation of breast fibroglandular volume only is shown in Fig. 4C.

Fig. 4.

Extraction of the fibroglandular map in the breast volume.

We compared mammographic and MR density for all patients in our high-risk cohort. Overall correlation between both modalities was calculated for all patients and then estimated in groups of lower density (MR density <20% representing mammographic groups of BIRADS 1 and 2) and higher density (MR density >20% or mammographic groups of BIRADS 3 and 4).

3. Results

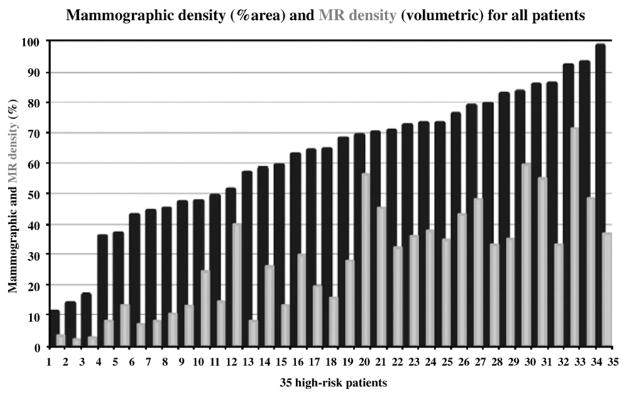

Among the 35 patients, mammographic density measures ranged from 11% to 98.2%. The mean and standard deviation (S.D.) of all mammographic densities were found at 61% and 22%, respectively, in our cohort. In that same group, values of MR density were found to be between 2% and 71.4%, with a mean of 28% and S.D. of 18%. Important differences between 2-D mammographic and 3-D MR densities were found in patients. Fig. 5 presents the example of a patient whose mammographic density was calculated as 56% (dense area from digitized mammogram), and her MR density was found to be 10%. Fig. 6 displays the measures of mammographic vs. MR density for all 35 high-risk women in our cohort. The mammographic densities were always higher than MR density; however, the differences were not consistent across all patients. Table 1 shows values of mean density obtained in groups of patients younger (n=26) and older than 50 years (n=9) in the high-risk cohort, using both modalities.

Fig. 5.

Difference in breast density measures between 2-D vs. 3-D modality.

Fig. 6.

Mammographic (black) and MR density (gray) measures for 35 high-risk patients, ordered by increasing mammographic density.

Table 1.

Mean Mammographic and MR densities in different age groups: before and after 50 yrs

| Mean density in age groups | Age <50 years (n=26; mean age, 39.7 years) | Age ≥50 years (n=9; mean age, 52.3 years) |

|---|---|---|

| Mammography (% area) | 65.3 | 50.8 |

| MRI (% volume) | 29.6 | 24.5 |

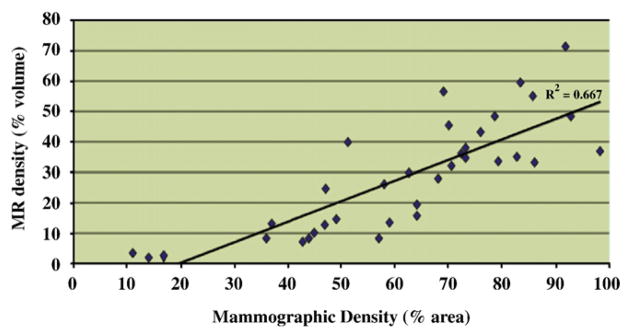

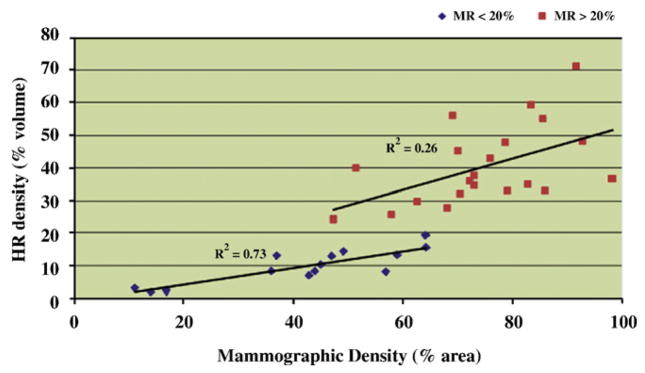

Fig. 7 displays a scatter plot of MR density vs. mammographic density for all patients. These results show an overall correlation of R2=.667 (P<.0001) between quantitative mammographic density and quantitative measures of MR density in our high-risk cohort. However, when measured among groups BIRADS 1 and 2 of mammographic density, the correlation between MRI and mammography was found to be significantly higher (R2=.732, P<.0001) than when measured among groups of BIRADS 3 and 4 (R2=.264, P<.017) as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 7.

Correlation between mammographic and MR breast density for 35 high-risk patients.

Fig. 8.

Correlation between mammographic and MR density in high-risk women with low (<20%) vs. high (>20%) MR density measures.

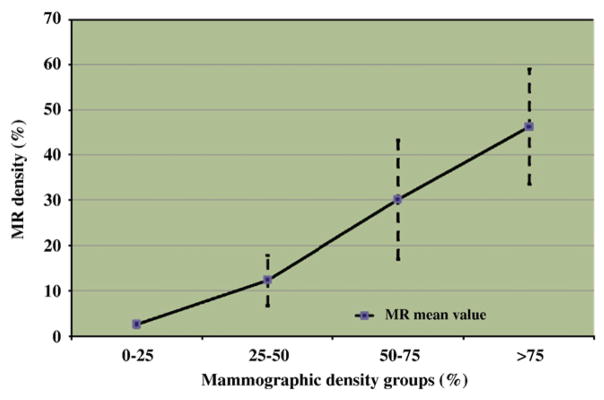

Finally, Fig. 9 presents breast density measures obtained using mammographic density compared with mean MR density. The range of MR density measures was found to be 1.5 times smaller than the range of mammographic densities. Fig. 9 also illustrates the higher correlation of mammographic and MR density measures in lower density groups than in denser categories (BIRADS 3 and 4), with very different ranges in volumetric MR density values measured in denser groups. Volumetric MR density seems to provide additional information on breast tissue composition in these categories.

Fig. 9.

Differences between mammographic and MR density among four groups of increasing mammographic density.

4. Discussion

Mammographic breast density is known to decrease in women after 50 years of age. In our cohort of 35 high-risk women, mean mammographic density values were found to be significantly higher (65.3%) in women less than 50 years than in women over 50 years, who had a mean mammographic density of 50.8% (P=.081). In comparison, in the same cohort, mean breast density values obtained using MRI were found to be 29.6% in the women less than 50 years of age and 24.5% in the women over 50 years of age (P=.4). As shown in Fig. 6, for all individuals, the range in MR density measures is smaller than the range of corresponding mammographic densities. These differences in breast density ranges are inherent to the 2-D vs. 3-D modality measures: quantitative mammography is performed on the 2-D projection of the entire breast, whereas MR density is a 3-D measure reflecting the ratio of breast fibroglandular tissue within the entire breast. As described in Ref. [20], comparing 2-D to 3-D density may prove to be very inaccurate in higher density cases since the projected results on mammography will really depend on tissue patterns present in the breast. For fattier breasts, differences in measures between 2-D and 3-D modalities may be minimal; however, when fibroglandular tissue patterns become denser, results in projected 2-D mammograms may not well represent the composition of 3-D MRI volumes. To illustrate this point, we show in Figs. 7 to 9 that in individuals with MR density less than 20% (corresponding to women with BIRADS levels 1 and 2 in mammographic density), MR and mammographic density provide similar information (or low density measures) on the breast under study; however, in patients with MR density higher than 20% (mammographic density BIRADS 3 and 4), the correlation between MR and mammographic density measures decreases and density values differ between mammography and MRI modalities, as shown in high mammographic density patients assessed with much lower MRI density values.

The important variations in density measures between modalities translate into differences in breast content and suggest that, for higher density values, mammographic density may not translate fibroglandular tissue composition as well as MR density. Lee et al. [11] found a twofold error between mammographic and MR density measures in dense patients and concluded that mammography has limited ability to assess density of fibroglandular tissue. Our results confirm these discrepancies between 2-D and 3-D breast density in our high-risk population. As described by Kopans [20], there is, therefore, an important need for an objective quantification of breast density using a 3-D modality such as MRI.

An advantage of our MR density technique is that the segmentation requires no user interaction for threshold decision and takes into account partial voluming, therefore, leading to a robust, low subjectivity technique.

We have previously demonstrated this technique robustness over common segmentation techniques such as manual delineation and global thresholding to quantify fibroglandular tissue volume in MRI data [12]. We also presented small intra- and interuser variability errors for MR density measures in 10 volunteers who underwent 2 consecutive noncontrast MRI scans (3% and 7%, respectively), suggesting that the breast MRI could be used for longitudinal studies in various populations. We showed good correlation (R2=.75) between MR and mammographic density for the group of 10 female volunteers [12]. These results were comparable with those previously published [10,11,21]. Graham et al. [10] assessed the correlation between quantitative mammographic density and two MRI parameters, relative water content (Pearson coefficient r=.79) and mean T2 relaxation time (r=−.61) in 42 women. Lee et al. [11] showed mammographic/MR density correlation of .63 using a qualitative evaluation of mammograms and quantitative measures of MR density in 40 women with fatty and mixed densities breasts. Their correlation rate fell to .34 for breasts with MR densities higher than 25%. Finally, Wei et al. [21] showed a high correlation between quantitative mammographic and MR density in 67 women. Several studies involved MRI coronal views that were manually thresholded and, therefore, required user interaction for final segmentation [21,22]. These studies show that there is a correlation between mammographic and MR density in the general population; however, in women with dense breasts, we showed that this correlation does not hold. Accurate volumetric measures of breast density are, therefore, needed in populations of women with high breast density.

Our technique, based on intensity regions segmentation, is dependent on the quality of the MRI data. Our technique also involves some user interaction to ensure an accurate segmentation of the breast tissue regions of interest. Therefore, depending on the anatomy and MRI imaging protocol, this technique can be time consuming and prone to reproducibility errors especially in very fatty breasts. However, there are no established techniques to eliminate these issues. Recent studies have used MRI-based breast density measures introducing various techniques aimed at simplifying the delineation process and potentially automating it. Some authors quantify density measures from breast MRI coronal data that provide very regular contours (breast circular shape). However, depending on patient anatomy, coronal views can be obscured by chest wall regions and, therefore, do not provide an accurate description of total breast volumes, often requiring additional interaction from the user to perform delineation of the breast volume [21,22]. Other techniques based on MRI axial data involve additional steps to extract the skin and segment the breast region, in particular, providing solutions to extract the lateral margins of the pectoralis muscles [23]; however, most studies must include operator involvement especially when the chest wall is connected to the fibroglandular tissue. There is a need for more automated MRI density techniques that could then be used directly in the clinic. The future of these MR density techniques will depend on the robustness and accuracy of breast segmentation within the image [23].

Currently, one of the main limitations of our technique is that it does not include any constraints on the data that is segmented within the delineated regions (breast contour), and therefore, it can lead to erroneous results if large artifacts, such as artifacts resulting from poor fat suppression, are present in the MRI slices. To avoid such artifacts in our resultant data, we visually assessed all studies to ensure sufficient image quality. Our next step in the development of automation will be to include constraints that will allow our technique to omit certain zones known to be artifacts and force the technique to include others (very bright regions such as cysts within the fibroglandular tissue, darker regions due to inhomogeneity of MRI data reconstruction) in the final segmentation.

Finally, our semiautomated technique performs well when fibroglandular tissue can be segmented from adipose tissue, that is, in women with some fibroglandular regions. Breasts with very little fibroglandular regions are more prone to errors (under- or overestimation of real fibroglandular regions) due to the difficulty of segmenting very thin fibroglandular regions within adipose tissue.

The standard measurement of breast density from mammograms has a number of limitations. The percentage area of dense tissue on mammograms is evaluated visually [24] or manually [25,26] to separate adipose from fibro-glandular tissue in 2-D regions. Other studies introduced more technically advanced methods [27,28], but objective classification of tissue remains an issue, and the inclusion of a wide variety of parameters in these new techniques increase their complexity and processing time. In addition, mammography suffers from other limitations including reader variations, lack of information due to the 2-D projection of the breast and, most importantly, limited applicability to populations with dense breasts. In addition, breast compression during the mammographic examination is variable; therefore, the aspect of density projected on the mammogram can be different on sequential examinations of the same patient. Finally, since it utilizes radiation, it is not possible to obtain frequent mammograms of patients, especially for high-risk younger women who would benefit from frequent screenings and for other groups for which the evaluation of breast composition would be valuable information in their breast cancer risk assessment.

Recent studies have introduced different models of quantitative mammographic measures, which differ from the quantification of the projected dense tissue on mammograms and introduce the concept of volumetric mammographic density [29]. Physical models of image acquisition were introduced [30] to correct the mammogram intensities and quantify volumetric information at each projection point. Other authors introduced a small calibration wedge to help measure the volume of compressed fibroglandular tissue [31,32]. Van Engeland et al. [22] introduced a physical model of image acquisition with the assumption that the breast is composed of two regions (breast and adipose tissue), and they mapped the thickness of fibroglandular tissue on mammograms. While their correlation with MRI volume was found to be high (.97), their technique presents important issues for dense breasts that affect their calibration and results. Several new quantitative mammographic measures are closer to a 3-D measure of fibroglandular tissue; however, they still need to be further tested on higher density populations to verify whether they could provide a robust and accurate measure of 3-D breast density [33].

Since MRI has become the increasingly recognized modality to screen specific populations of high-risk women (positive for BRCA1 or 2 genes, or strong family history), we believe that MR density could be assessed on a more regular basis for these populations and used as a component of their breast cancer risk assessment. For these high-risk women who need to be screened well before 50 years, a new MRI stratification system could be developed to potentially improve their risk assessment for breast cancer, using noncontrast MRI data. The fact that MR density is obtained from noncontrast MRI data could also lead to a shorter and, therefore, less expensive scan for density measurement purposes only. Magnetic resonance imaging data provide information on fibroglandular tissue patterns (centered at nipple or scattered all over) and composition (adipose tissue involvement patterns within fibroglandular tissue or localized in specific regions) that may provide useful additional 3-D measures that could be easily tested in large population studies. Recent articles have described the use of MRI not only to assess density [23,34] but also to quantify effects of preventative treatments aimed at reducing breast cancer risk by reducing breast density [35–37].

5. Conclusion

The objectives of this study were to apply our semiautomated segmentation technique quantifying breast fibroglandular tissue and total breast volumes from MRI data to compare quantitative measures of “MR density” with mammographic densities from a cohort of 35 patients at high-risk of breast cancer. Our segmentation technique involved automated classification of MRI data using tissue memberships, providing a more objective assessment of fibroglandular tissue volume than thresholding or manual delineation techniques. Our results on this high-risk population correlate with previously published results for women with fatty to medium density breasts, but it shows very important discrepancies between 2-D and 3-D density in all women with more than 20% density with MRI, corresponding to women with mammographic density higher than BIRADS 1 to 2, potentially leading to very different risk assessment for these women. We believe that MR volumetric density measures should help better assess breast composition in populations of women with dense breasts. As our quantitative MRI technique was shown to be very robust across different levels of breast density, it could also improve the monitoring of preventative treatment effects in patients for whom measures of breast density will be recorded before and after treatment.

References

- 1.Boyd NF, Lockwood GA, Byng JW, et al. Mammographic densities and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1133–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd NF, Greenberg C, Lockwood GA, et al. Effects of a 2 years of a low fat high-carbohydrate diet on radiologic features of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(7):488–96. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.7.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, et al. Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(21):1622–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.21.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hersh MR. Imaging the dense breast. Appl Radiol. 2004;33(1):22–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilanus-Linthorst MM, Obdeijn IM, Bartels KC. First experiences in screening women at high risk for breast cancer with MR imaging. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;63(1):53–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1006480106487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Comparison of the performance of screening, mammography, physical examination and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165–75. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhl CK. High-risk screening: multi-modality surveillance of women at high-risk of breast cancer, L. Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2002;21 (3 Suppl):103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnall M. Breast MR imaging. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41 (1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(03)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klifa C, Partridge S, Lu Y, Hylton N. Quantification of breast tissue texture from magnetic resonance imaging data. Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2003 (ISMRM); Toronto. July 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham SJ, Bronskill MJ, Byng JW, et al. Quantitative correlation of breast tissue parameters using MR and X-ray mammography. Br J Cancer. 1996;73(2):162–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee NA, Rusinek H, Weinreb J, et al. Fatty and fibroglandular tissue volume in the breasts of women 20–93 years old: comparison of X-ray mammography and computer assisted MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168(2):501–6. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.2.9016235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klifa C, Carballido-Gamio J, Wilmes L, et al. Quantification of breast tissue index from MR data using fuzzy clustering. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2004;3:1667–70. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1403503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prevrhal S, Shepherd JA, Smith-Bindman R, Cummings SR, Kerlikowske K. Accuracy of mammographic breast density analysis: results of formal operator training. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(11):1389–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partridge SC, Gibbs JE, Lu Y, Esserman LJ, Sudilovsky D, Hylton NM. Accuracy of MR imaging for revealing residual breast cancer in patients who have undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1193–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Radiology. Breast imaging reporting and data system (BIRADS) 3. Reston (VA): American College of Radiology; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carballido-Gamio J, Klifa C, Majumdar S, Hylton N. Application of a fuzzy inference system to the quantification of 3D magnetic resonance imaging of breast tissue. San Diego: SPIE Medical Imaging; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulkarni AD. Computer vision and fuzzy-neural systems. 1. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall; 2001. Fuzzy logic fundamentals; pp. 61–101. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bezdek JC. Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithm. New York: Plenum; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bezdek JC, Hall LO, Clarke LP. Review of MR segmentation techniques using pattern recognition. Med Phys. 1993;20(4):1033–48. doi: 10.1118/1.597000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kopans DB. Basic physics and doubts about relationship between mammographically determined tissue density and breast cancer risk. Radiology. 2008;246:348–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461070309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, Chan HP, Helvie MA, et al. Correlation between mammographic density and volumetric fibroglandular tissue estimated on breast MR images. Med Phys. 2004;31(4):933–42. doi: 10.1118/1.1668512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Engeland S, Snoeren PR, Huisman H, et al. Volumetric breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2006;25(3):273–82. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2005.862741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nie K, Chen JH, Chan S, et al. Development of a quantitative method for analysis of breast density based on three-dimensional breast MRI. Med Phys. 2008;35(12):5253–60. doi: 10.1118/1.3002306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe JN. Breast Patterns as an index of risk for developing breast cancer. AJR. 1976;126:1130–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byng JW, Boyd NF, Jong RA, et al. Quantitative analysis of mammographic densities. Phys Med Biology. 1994;39:1629–38. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/39/10/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe JN, Saftlas A, Salane M. Mammographic parenchymal patterns and quantitative evaluation of mammographic densities: a case control study. AJR. 1987;148:1087–92. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.6.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byng JW, Yaffe MJ, Jong RA, et al. Analysis of mammographic density and breast cancer risk from digitized mammograms. RadioGraphics. 1998;18:1587–98. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.6.9821201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrow WM, Paranjape RB, Rangayyan RM, et al. Region based contrast enhancement of mammograms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1992;11(3):392–406. doi: 10.1109/42.158944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCormack V, Highnam R, Perry N, dos Santos Silva I. Comparison of a new and existing method of mammographic density measurement: intramethod reliability and associations with known risk factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(6):1148–54. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Highnam RP, Brady JM. Mammographic image analysis. Chap. 2 Norwell: Kluwer Academic Press; 1999. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawluczyk O, Augustine BJ, Yaffe MJ, et al. A volumetric method for estimation of breast density on digitized screen film mammograms. Med Phys. 2003;30(3):352–64. doi: 10.1118/1.1539038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malkov S, Wang J, Shepherd J. Novel single x-ray absorptiometry method to solve for volumetric breast density in mammograms with paddle tilt. Proceedings of the SPIE. 2007;6510:651035. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaffe M. Measurement of mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(3):209. doi: 10.1186/bcr2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khazen M, Warren R, Boggis C, et al. A pilot study of compositional analysis of the breast and estimation of breast mammographic density using three-dimensional T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(9):2268–74. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eng-Wong J, Orzano-Birgani J, Chow C, et al. Effect of raloxifene on mammographic density and breast magnetic resonance imaging in premenopausal women at increased risk for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(7):1696–701. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orisamolu A, Klifa C, Suzuki C, et al. MRI quantitative changes of breast tissue composition with short-term tamoxifen treatment in cancer patients. Int Soc Magn Reson Med 2009 (ISMRM); Honolulu. April 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klifa C, Sand S, Vora L, Press M, Orisamolu A, Pike M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging quantification of breast density in BRCA carriers following gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHA)-based hormonal chemoprevention. 2009 ASCO Annual Meeting; Orlando. May 28–June 2. [Google Scholar]