Abstract

Objective To determine casemix adjusted hospital level utilization of minimally invasive surgery for four common surgical procedures (appendectomy, colectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and lung lobectomy) in the United States.

Design Retrospective review.

Setting United States.

Participants Nationwide inpatient sample database, United States 2010.

Methods For each procedure, a propensity score model was used to calculate the predicted proportion of minimally invasive operations for each hospital based on patient characteristics. For each procedure, hospitals were categorized into thirds (low, medium, and high) based on their actual to predicted proportion of utilization of minimally invasive surgery.

Main outcome measures The primary outcome measures were the actual and predicted proportion of procedures performed with minimally invasive surgery. Secondary outcome measures included surgical complications and hospital characteristics.

Results Mean hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery was 71.0% (423/596) for appendectomy (range 40.9-93.1% (244-555)), 28.4% (154/541) for colectomy (6.7-49.8% (36/541-269/541)), 13.0% (65/499) for hysterectomy (0.0-33.6% (0/499-168/499)), and 32.0% (67/208) for lung lobectomy (3.6-65.7% (7.5/208-137/208)). Utilization of minimally invasive surgery was highly variable for each procedure type. There was noticeable discordance between actual and predicted utilization of the surgery (range of actual to predicted ratio for appendectomy 0-1.49; colectomy 0-3.88; hysterectomy 0-6.68; lung lobectomy 0-2.51). Surgical complications were less common with minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery, respectively: overall rate for appendectomy 3.94% (1439/36 513) v 7.90% (958/12 123), P<0.001; for colectomy: 13.8% (1689/12 242) v 35.8% (8837/24 687), P<0.001; for hysterectomy: 4.69% (270/5757) v 6.64% (1988/29 940), P<0.001; and for lung lobectomy: 17.1% (367/2145) v 25.4% (971/3824), P<0.05. High utilization of minimally invasive surgery was associated with urban location (appendectomy: odds ratio 4.66, 95% confidence interval 1.17 to 18.5; colectomy: 4.59, 1.04 to 20.3; hysterectomy: 15.0, 2.98 to 75.0), large hospital size (hysterectomy: 8.70, 1.62 to 46.8), teaching hospital (hysterectomy: 5.41, 1.27 to 23.1), Midwest region (appendectomy: 7.85, 1.26 to 49.1), south region (appendectomy: 21.0, 3.79 to 117; colectomy: 10.0, 1.83 to 54.7), and west region (appendectomy: 9.33, 1.48 to 58.8).

Conclusion Hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery for appendectomy, colectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and lung lobectomy varies widely in the United States, representing a disparity in the surgical care delivered nationwide.

Introduction

Surgical complications represent a substantial burden of harm to patients and in the United States alone are estimated to cost $25b annually.1 For select procedures, however, complications can be reduced by using minimally invasive surgery. Strong evidence has shown superior patient outcomes for this type of surgery over traditional open surgery for many common procedures.

A Cochrane review of 67 randomized control trials concluded that laparoscopic appendectomy was associated with a reduction in surgical site infections, postoperative pain, and time to return to normal activity compared with open surgery.2 A 2004 randomized controlled trial of 863 colorectal resections established that laparoscopy was associated with superior patient outcomes (reduction in postoperative pain, postoperative analgesic requirements, and hospital length of stay) compared with open surgery,3 a finding later affirmed by a Cochrane review of 25 randomized controlled trials.4 For hysterectomy for benign disease, a Cochrane review of 34 randomized controlled trials found that laparoscopy was associated with a reduction in surgical site infections, hospital length of stay, time to return to normal activities, and blood loss compared with open surgery.5 Similarly, a 2007 meta-analysis comparing video assisted thoracic surgery with open thoracotomy for lung lobectomy for cancer concluded that the minimally invasive operation was associated with a reduction in postoperative pain, analgesia requirement, and time to return to normal activity and with improved adherence to chemotherapy and postoperative vital lung capacity.6 Furthermore, in the setting of cancer, minimally invasive colectomy, hysterectomy, and lung lobectomy have been associated with the same stage specific survival as the open approach.3 6 7

Despite the extensive body of evidence to support the use of minimally invasive surgery, choice of surgery is often a matter of surgeon preference. Little is known about the current adoption of laparoscopy in US hospitals. We hypothesized that there is wide variation in the utilization of minimally invasive surgery and designed a study to measure this potential disparity in surgical care.

Methods

Population

We carried out a retrospective analysis using information from the United States nationwide inpatient sample database. This database, the largest publicly available all payer database in the United States, was created and is maintained by the Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality. It includes patient level hospital discharge data from a representative stratified sample of 1051 US hospitals in 45 states.8 We included hospitalizations for common procedures at hospitals that performed at least 10 of these procedures between 1 January and 31 December 2010.

Procedures of interest

We evaluated three common procedures that have strong evidence to support the use of minimally invasive surgery and also have a procedure code for both a minimally invasive and an open surgery according to ICD-9-CM (international classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification).2 3 4 5 7 The procedures included appendectomy (laparoscopic 47.01; open 47.09), partial colectomy (laparoscopic 17.3; open 45.7), and total abdominal hysterectomy (laparoscopic 68.41; open 68.4). We also evaluated lung lobectomy (thoracoscopic 32.41 and 32.30; open 32.49 and 32.39) to represent a common procedure where evidence supporting one approach over the other is less well established.6

The nationwide inpatient sample includes records for each hospitalization and does not identify readmissions for the same patient. To avoid double counting patients who were readmitted to a hospital or transferred from a different hospital, we excluded hospitalizations with the operation performed more than one day before admission (indicating that patients were discharged and then readmitted) and those presenting with a complication (ICD-9 codes 996-999 and v50-v59), sepsis (038), or a drain (54.91). We also excluded surgery that involved several procedures.

Utilization of minimally invasive surgery

To evaluate the association between patient factors and the utilization of minimally invasive surgery, we compared the actual utilization for each hospital with its predicted utilization. We used a logistic regression model, which we refer to as a propensity score model, to calculate the expected number and proportion of events that can be compared with the observed. We referred to the model as a propensity score to make a distinction from the models of the outcome and those of the expected proportion of events. The predicted utilization was calculated using a logistic regression propensity score model including patient demographics and the variables that contribute to the Elixhauser comorbidity score,9 with stepwise selection (P<0.3 to enter, P<0.2 to stay) without interaction terms. As two additional prediction models including a logistic regression model allowing all two-way interactions and a model using high dimensional variable selection generated similar predicted probabilities, we present the results of the simple model only.10

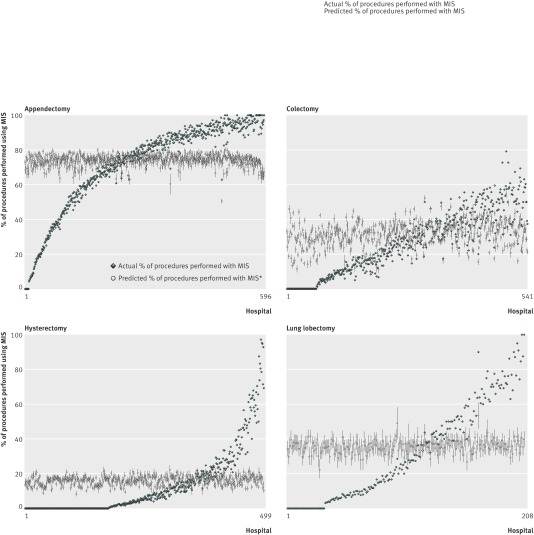

To describe hospital level utilization of minimally invasive surgery for each procedure, we categorized hospitals into thirds (low, medium, and high) based on their actual to predicted proportion of utilization of such surgery. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare differences in utilization between the thirds. To better describe variation on a more granular level, for each procedure type we plotted each hospital’s actual proportion of operations performed using minimally invasive surgery and each hospital’s predicted proportion of operations performed using minimally invasive surgery. We plotted the data with hospitals on the x axis and utilization of minimally invasive surgery on the y axis. Hospitals are listed on the x axis in increasing order from lowest to greatest observed to predicted ratio of utilization of minimally invasive surgery.

Identification of predictors of variation by hospital characteristics

We evaluated the influence of hospital characteristics on high utilization of minimally invasive surgery using a generalized linear mixed logistic regression model with a random intercept for hospital to account for the correlation of procedures within hospitals. Potential hospital level predictors included location (rural or urban), size (small, medium, or large), teaching status, region (north east, Midwest, south, or west), and type (government, private not for profit, private for profit). The nationwide inpatient sample database predetermined the category definitions. We adjusted for the Elixhauser comorbidity score in this model. Analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Surgical complications

As a secondary analysis, we measured complications associated with minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery for each procedure type using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators for surgical care.11 These included wound infection, wound dehiscence, deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, sepsis, postoperative hemorrhage or hematoma, postoperative metabolic derangements, accidental puncture or laceration, and in-patient death during the index hospitalization. The generalized linear mixed logistic regression model used to identify the incidence of complications by procedure type used the same hospital and individual level predictors as the above described model to predict utilization of minimally invasive surgery with the addition of minimally invasive surgery as a predictor rather than as the outcome.

Results

Table 1 lists the percentage of hospitals in the low, medium, and high categories for utilization of minimally invasive surgery by hospital location, size, teaching status, region, and financial type. Out of the 1051 hospitals in the nationwide inpatient sample database, the inclusion criteria for our analysis were met by 596 hospitals for appendectomy, 541 hospitals for colectomy, 499 hospitals for hysterectomy, and 208 hospitals for lung lobectomy. The mean hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery was 71.0% (423/596) for appendectomy, 28.4% for colectomy (154/541), 13.0% (64/499) for hysterectomy, and 32.0% (66/208) for lung lobectomy. Hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery varied widely for all four procedures, with a significant increase in utilization from the low to medium third hospitals and from the medium to high third hospitals (mean utilization by third for appendectomy: low 40.9% (81/199), medium 78.8% (n=156), high 93.1% (n=185), P<0.001; colectomy: low 6.7% (12/180), medium 29.0% (n=52), high 49.8% (n=90), P<0.001; hysterectomy: low 0.0% (0/166), medium 6.2% (n=10), high 33.6% (n=56), P<0.001; lung lobectomy: low 3.6% (3/69), medium 26.7% (n=18), high 65.7% (n=45), P<0.001). Some hospitals had zero utilization of minimally invasive surgery for the four procedures: appendectomy 1.6% (9/596), colectomy 11.5% (62/541), hysterectomy 35% (174/499), and lung lobectomy 15.9% (33/208). Conversely, greater than 75% utilization of minimally invasive surgery was observed in hospitals: appendectomy 56.4% (336/596), colectomy 0.7% (4/541), hysterectomy 1.6% (8/499), and lung lobectomy 8.2% (17/208).

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospitals with low, medium, and high utilization of minimally invasive surgery by procedure of interest. Values are percentages

| Characteristics | Appendectomy (596 hospitals) | Colectomy (541 hospitals) | Hysterectomy (499 hospitals) | Lung lobectomy (208 hospitals) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | ||||

| Hospital location: | |||||||||||||||

| Urban | 61.1 | 75.9 | 79.9 | 67.2 | 82.3 | 80.6 | 52.6 | 85.4 | 38.7 | 89.9 | 92.9 | 94.2 | |||

| Hospital size: | |||||||||||||||

| Small | 28.8 | 22.1 | 23.1 | 31.1 | 19.3 | 16.7 | 26.3 | 17.1 | 16.3 | 13.0 | 10.0 | 5.8 | |||

| Medium | 34.9 | 31.2 | 29.2 | 23.3 | 32.1 | 35.0 | 36.6 | 31.7 | 26.5 | 23.2 | 12.9 | 29.0 | |||

| Large | 36.3 | 46.7 | 47.7 | 45.6 | 48.6 | 48.3 | 37.1 | 51.2 | 57.2 | 63.8 | 77.1 | 65.2 | |||

| Teaching status: | |||||||||||||||

| Teaching | 26.8 | 27.6 | 24.6 | 21.1 | 40.9 | 23.9 | 11.4 | 37.3 | 39.2 | 47.8 | 54.3 | 44.9 | |||

| Hospital region: | |||||||||||||||

| North east | 25.8 | 20.1 | 10.6 | 26.1 | 20.4 | 15.0 | 17.7 | 19.0 | 20.5 | 21.8 | 14.3 | 26.1 | |||

| Midwest | 23.2 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 25.0 | 19.9 | 21.7 | 26.3 | 19.6 | 21.1 | 30.4 | 21.4 | 8.7 | |||

| South | 28.3 | 37.2 | 45.2 | 26.1 | 38.7 | 41.6 | 36.6 | 43.0 | 34.9 | 30.4 | 41.4 | 44.9 | |||

| West | 22.7 | 21.1 | 24.1 | 22.8 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 19.4 | 18.4 | 23.5 | 17.4 | 22.9 | 20.3 | |||

| Hospital type: | |||||||||||||||

| Private, for profit | 12.6 | 11.5 | 24.1 | 17.8 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 17.1 | 15.8 | 14.4 | 10.2 | 12.9 | 15.9 | |||

| Private, not for profit | 70.7 | 72.4 | 63.3 | 67.2 | 70.7 | 72.8 | 62.3 | 70.9 | 72.3 | 79.7 | 71.4 | 73.9 | |||

| Government | 16.7 | 16.1 | 12.6 | 15.0 | 13.3 | 11.1 | 20.6 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 10.1 | 15.7 | 10.2 | |||

There was sharp discordance between a hospital’s observed and predicted proportion of procedures performed using minimally invasive surgery (figure). The range of the actual to predicted ratio of utilization was 0-1.49 for appendectomy, 0-3.88 for colectomy, 0-6.68 for hysterectomy, and 0-2.51 for lung lobectomy.

Percentage of procedures performed using minimally invasive surgery (MIS) by hospital. Hospitals are ranked in increasing order from lowest to highest observed to predicted ratio of MIS utilization. Each point represents one hospital. For predicted values, error bars are 95% confidence intervals. *Case mix adjusted (predicted rate). Each diamond represents one hospital

For the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators, the overall complication rates for minimally invasive surgery compared with open surgery were, respectively: appendectomy: 3.94% (1439/36 513) v 7.90% (958/12 123), P<0.001; colectomy: 13.8% (1689/12 242) v 35.8% (8837/24 687), P<0.001; hysterectomy: 4.69% (270/5757) v 6.64% (1988/29 940), P<0.001; and lung lobectomy: 17.1% (367/2145) v 25.4% (971/3824), P<0.05. Using a risk adjusted model, individual complications for each procedure were either decreased or no different with the minimally invasive surgery approach, with most exhibiting a decrease (table 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratios of postoperative complication rates of minimally invasive versus open surgery using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators for surgical care

| Complications | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appendectomy | Colectomy | Hysterectomy | Lung lobectomy | |

| Surgical site infection or abscess | 0.29 (0.23 to 0.36) | 0.34 (0.24 to 0.13) | 0.48 (0.28 to 0.83) | 0.41 (0.17 to 1.0) |

| Wound dehiscence | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.13) | 0.15 (0.10 to 0.22) | 0.15 (0.03 to 0.61) | Rare complication* |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0.97 (0.25 to 3.83) | 0.37 (0.20 to 0.69) | 0.59 (0.14 to 2.54) | No complication† |

| Pneumonia | 0.53 (0.42 to 0.66) | 0.38 (0.33 to 0.43) | 0.60 (0.38 to 0.92) | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.72) |

| Sepsis | 0.38 (0.31 to 0.45) | 0.12 (0.10 to 0.14) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.59) | 0.43 (0.27 to 0.68) |

| Postoperative hemorrhage or hematoma | 0.80 (0.59 to 1.07) | 0.78 (0.08 to 0.67) | 0.49 (0.37 to 0.64) | 0.55 (0.37 to 0.81) |

| Postoperative physiologic and metabolic derangements | 0.44 (0.08 to 0.38) | 0.39 (0.04 to 0.36) | 0.43 (0.32 to 0.57) | 0.79 (0.63 to 0.98) |

| Accidental puncture or laceration | 0.37 (0.22 to 0.63) | 0.34 (0.29 to 0.41) | 1.19 (0.11 to 1.43) | 0.34 (0.18 to 0.64) |

| Death | 0.21 (0.09 to 0.50) | 0.15 (0.12 to 0.19) | No complication† | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.94) |

*Not estimable. One event in group undergoing minimally invasive surgery.

†Not estimable. No events in group undergoing minimally invasive surgery

High utilization of minimally invasive surgery was associated with urban location (appendectomy: odds ratio 4.66, 95% confidence interval 1.17 to 18.5; colectomy: 4.59, 1.04 to 20.3; hysterectomy: 15.0, 2.98 to 75.0), large hospital size (hysterectomy: 8.70, 1.62 to 46.8), teaching hospital (hysterectomy: 5.41, 1.27 to 23.1), Midwest region (appendectomy: 7.85, 1.26 to 49.1), south region (appendectomy: 21.0, 3.79 to 117; colectomy: 10.0, 1.83 to 54.7), and west region (appendectomy: 9.33, 1.48 to 58.8, table 3). Low utilization of minimally invasive surgery was associated with teaching hospital (colectomy: odds ratio 0.19, 95% confidence interval 0.05 to 0.76), Midwest region (lung lobectomy: 0.02, 0.001 to 0.31), private not for profit hospitals (appendectomy: 0.16, 0.03 to 0.84), and government hospitals (appendectomy: 0.08, 0.01 to 0.60).

Table 3.

Hospital predictors of high laparoscopic utilization shown as odds ratios determined using a hierarchical logistic regression

| Hospital predictors | Appendectomy | Colectomy | Hysterectomy | Lung lobectomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location: | ||||

| Rural | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Urban | 4.66 (1.17 to 18.5) | 4.59 (1.04 to 20.3) | 15.0 (2.98 to 75.0) | 4.04 (0.14 to 120) |

| Size: | ||||

| Small | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Medium | 0.71 (0.15 to 3.27) | 5.07 (0.98 to 26.1) | 1.70 (0.28 to 10.3) | 18.7 (0.64 to 547) |

| Large | 1.58 (0.38 to 6.61) | 2.53 (0.54 to 11.8) | 8.70 (1.62 to 46.8) | 2.70 (0.12 to 62.2) |

| Teaching status: | ||||

| Non-teaching | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Teaching | 0.70 (0.18 to 2.73) | 0.19 (0.05 to 0.76) | 5.41 (1.27 to 23.1) | 0.29 (0.04 to 1.92) |

| Region: | ||||

| North east | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Midwest | 7.85 (1.26 to 49.1) | 4.28 (0.71 to 25.9) | 1.28 (0.19 to 8.81) | 0.02 (0.001 to 0.31) |

| South | 21.0 (3.79 to 117) | 10.0 (1.83 to 54.7) | 1.10 (0.18 to 6.73) | 0.56 (0.06 to 5.67) |

| West | 9.33 (1.48 to 58.8) | 3.63 (0.57 to 23.2) | 2.32 (0.31 to 17.2) | 0.28 (0.02 to 3.86) |

| Type | ||||

| Private, for profit | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Private, not for profit | 0.16 (0.03 to 0.84) | 3.58 (0.65 to 19.5) | 2.11 (0.34 to 13.0) | 0.71 (0.05 to 10.3) |

| Government | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.60) | 0.94 (0.10 to 8.44) | 1.06 (0.11 to 10.1) | 0.38 (0.01 to 12.9) |

Discussion

Disparity in quality

It has been well established that minimally invasive surgery is associated with lower complications and improved postoperative recovery. Despite these benefits, two standards of care remain in existence because patient candidacy and the choice of operations are often discretionary, based on surgeon preference. In the United States we found wide variation in the use of minimally invasive surgery by hospital after adjusting for differences in a hospital’s unique patient population. This study has important implications for quality improvement. Based on our findings, many hospitals have an opportunity to decrease surgical complications by increasing utilization of minimally invasive surgery.

Implications for reduction in surgical site infection

Surgical site infection, a leading quality indicator in healthcare, is one important quality metric that is noticeably decreased with use of minimally invasive surgery. Surgical site infections occur in 8-15% of open colorectal operations4 12 13 at an estimated cost of $1398 per patient secondary to prolonged hospitalization, wound care, and wound complications.14 In addition, the presence of a surgical site infection during a hospitalization is a leading risk factor for hospital readmission after colon surgery (odds ratio 1.18, 95% confidence interval 1.08 to 1.29).15 Hospitals have struggled to find innovative ways to decrease surgical site infections and there is a paucity of interventions with an established benefit beyond current practices. However, one intervention that is often overlooked is minimally invasive surgery. The decreased incision size associated with laparoscopy results in less subcutaneous dead space and thus a lower risk of bacterial contamination.16 A 2005 Cochrane review of 25 randomized controlled trials concluded that laparoscopic colectomy was associated with a 0.56 risk ratio of surgical site infections compared with open surgery.4 Similarly, a 2009 Cochrane review of 34 randomized controlled trials concluded that laparoscopic hysterectomy was associated with a 0.31 risk ratio of surgical site infections compared with open surgery.5 In our analysis using Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators for surgical care, we noted fewer wound, infectious, thrombotic, pulmonary, and mortality complications associated with minimally invasive surgery. Based on our findings, increased hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery at many US hospitals represents a tremendous opportunity to prevent surgical site infection events.

Hospital factors

We found that rural hospitals were less likely to perform minimally invasive surgery for three of the four procedures studied (appendectomy, colectomy, and hysterectomy, the fourth being lobe lobectomy). This disparity may be due to the broad range of surgical services some surgeons in rural areas are required to provide17 18 and a scarcity of surgical specialists in such areas with advanced skills in minimally invasive surgery.19 Alternatively, the disparity may be a function of a lack of patient awareness about surgical options, decreased competition for patients, or a lack of minimally invasive surgery equipment, staff, or support in rural areas. Other hospital characteristics showed no association or an irregular pattern of association with utilization of minimally invasive surgery. For instance, large hospital size was not associated with use with the exception of hysterectomy carried out laparascopically. Teaching status was associated with high utilization of minimally invasive surgery for hysterectomy, low utilization for colectomy, and no association for appendectomy or lung lobectomy, indicating no pattern of association across procedure types. By geographic region, the north east was associated with low utilization of minimally invasive appendectomy, the south was associated with high utilization of minimally invasive appendectomy and colectomy, and the Midwest was associated with low utilization of minimally invasive lung lobectomy. Regional variations that we observed may be due to more extensive specialty specific training in minimally invasive surgery in some areas. Moreover, hospital and regional attitudes towards minimally invasive surgery may vary, with some areas having a more minimally invasive surgery culture and others a more open surgery culture.

Opportunities for training

One reason that hospitals may be underperforming minimally invasive surgery is variability in appropriate training in residency and fellowship. Residents and fellows learn in an apprenticeship model, yet for many, the surgeons they learn from may lack advanced skills in minimally invasive surgery. In a survey of US obstetric and gynecology residency programs in 2006, only 69% had formal laparoscopy training.20 In a national survey of colorectal surgeons in 2009, lack of adequate operative time and formal training were the main reasons cited by the surgeons for not offering laparoscopic colon resections.21 Owing to this lack of exposure to minimally invasive surgery, training programs are beginning to implement formal education in this type of surgery during residency. In one general surgery program where a one month intensive advanced training program in minimally invasive surgery was implemented, 70% of postgraduate residents who had undergone the training believed that it was essential to their current practice.22 One strategy that hospitals may consider in managing surgeons who cannot or choose not to acquire skills for performing minimally invasive surgery is to create a division of labor where patients who are not candidates for minimally invasive surgery are cared for by these surgeons. Increased standardization of competencies in minimally invasive surgery in surgical residency is needed to tackle wide variations in training.

Implications for transparency

Some patients who are candidates for minimally invasive surgery are not informed of an option before undergoing open surgery. Comprehensive shared decision making tools to properly inform patients about the options of minimally invasive and open surgery are needed. A Cochrane review of 86 studies on shared decision making showed that patients with decision aids have increased knowledge and more accurate risk perception and are more likely to choose less invasive options.23 In one study, the researchers found that among 201 patients with newly diagnosed clinical stage I or II breast cancer, those given a decision aid were more likely to chose breast conserving therapy over mastectomy.24 Furthermore, hospital utilization of laparoscopy is easily measured and should accompany publically reported surgical outcomes for a hospital to better inform patients. Transparency of hospital rates of minimally invasive surgery could create incentives for hospitals to achieve rates of minimally invasive surgery consistent with best practices and to optimize their surgical outcomes. Rates of minimally invasive surgery should be evaluated in the context of national benchmarks. Such transparency could increase the appropriate application of minimally invasive surgery to patient care and decrease variation through increased accountability. A 2012 study of utilization of percutaneous coronary intervention procedures found that public reporting was associated with a 5% reduction in procedures performed, with no difference in patient outcomes, suggesting the impact of public reporting to incentivize more appropriate care.25 We submit that a hospital’s propensity adjusted observed to predicted ratio of minimally invasive surgery be used as one additional quality measure in surgical care.

Limitations of this study

This study has some important limitations. Administrative claims data can have incomplete coding, particularly of pre-existing conditions.26 However, large series have shown optimal patient outcomes in high risk populations for minimally invasive appendectomy, colectomy, and hysterectomy.27 28 29 30 31 32 Additionally, the propensity score predictions are based on current practice and may not reflect the optimal utilization rate of minimally invasive surgery. Another limitation is the lack of information available in the database for physician factors, such as laparoscopic training and experience that may influence the choice of procedure. This study focused on hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery, but further research is needed to determine the clinician level factors that influence utilization of minimally invasive surgery. Selection bias of patients is not accounted for and may detract from the observed difference in surgical complications.

Conclusions

Many hospitals in the United States have low utilization of minimally invasive surgery while many others have high utilization. Hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery by procedure may be a meaningful process measure in healthcare to complement existing and maturing outcome measures of surgical care. Important ways to deal with this disparity may be more standardized postgraduate training, training of surgeons currently in practice, transparency of hospital rates of utilization of minimally invasive surgery, and better information for patients.

What is already known on this topic

For many surgical procedures large randomized control trials and Cochrane reviews have established the superior outcomes of minimally invasive surgery for candidate patients, including reduced rates of surgical site infections, decreased pain, and shorter hospitalizations

Despite superior outcomes, hospitals may only offer and surgeons may only perform open surgery, and many patients who are candidates for minimally invasive surgery will undergo open surgery

The magnitude of variation in use of minimally invasive surgery as a disparity in healthcare in the United States has not been well described

What this study adds

After adjusting for casemix, in the United States there was wide variation in hospital utilization of minimally invasive surgery for appendectomy, colectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, and lung lobectomy

Despite a similar case mix, hospitals had markedly different rates for performing minimally invasive surgery for the common procedures studied, suggesting that use of minimally invasive surgery adjusted for casemix could be used as a new quality measure

The disparity in appropriateness of operations offered between hospitals has important implications for training, informed consent, and patient empowerment through data transparency

Contributors: All the authors designed and conceived the study; collected, managed, analysed, and interpreted the data; and prepared, reviewed, or approved the manuscript. MC had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. She is guarantor.

Funding: None received.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: MM who receives royalties from Bloomsbury Press for a published book; no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: The technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from Susan Hutfless at shutfle1@jhmi.edu.

Transparency: MC affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted, and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g4198

References

- 1.Mangano DT. Perioperative medicine: NHLBI working group deliberations and recommendations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2004;18:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauerland S, Jaschinski T, Neugebauer EA. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;10:CD001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:2050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker J, Muller JM. Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;3:CD003145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD003677.19588344 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng D, Downey RJ, Kernstine K, Stanbridge R, Shennib H, Wolf R, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery in lung cancer resection: a meta-analysis and systematic review of controlled trials. Innovations (Phila) 2007;2:261-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galaal K, Bryant A, Fisher AD, Al-Khaduri M, Kew F, Lopes AD. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for the management of early stage endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD006655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP): 2010. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- 9.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;361:8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mogun H, Brookhart MA. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology 2009;20:512-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overview of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators. 2013. www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/psi_resources.aspx.

- 12.Aimaq R, Akopian G, Kaufman HS. Surgical site infection rates in laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery. Am Surg 2011;77:1290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiran RP, El-Gazzaz GH, Vogel JD, Remzi FH. Laparoscopic approach significantly reduces surgical site infections after colorectal surgery: data from national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg 2010;211:232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimick JB, Chen SL, Taheri PA, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Campbell DA Jr. Hospital costs associated with surgical complications: a report from the private-sector National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wick EC, Shore AD, Hirose K, Ibrahim AM, Gearhart SL, Efron J, et al. Readmission rates and cost following colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:1475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Vivo A, Mancuso A, Giacobbe A, Priolo AM, De Dominici R, Maggio Savasta L. Wound length and corticosteroid administration as risk factors for surgical-site complications following cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:355-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanBibber M, Zuckerman RS, Finlayson SR. Rural versus urban inpatient case-mix differences in the US. J Am Coll Surg 2006;203:812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heneghan SJ, Bordley J 4th, Dietz PA, Gold MS, Jenkins PL, Zuckerman RJ. Comparison of urban and rural general surgeons: motivations for practice location, practice patterns and education requirements. J Am Coll Surg 2005;201:732-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson MJ, Lynge DC, Larson EH, Tachawachira P, Hart LG. Characterizing the general surgery workforce in rural America. Arch Surg 2005;140:74-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stovall DW, Fernandez AS, Cohen SA. Laparoscopy training in United States obstetric and gynecology residency programs. JSLS 2006;10:11-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moloo H, Haggar F, Martel G, Grimshaw J, Coyle D, Graham ID, et al. The adoption of laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a national survey of general surgeons. Can J Surg 2009;52:455-62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin RC 2nd, Kehdy FJ, Allen JW. Formal training in advanced surgical technologies enhances the surgical residency. Am J Surg 2005;190:244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Col NF, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;10:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, Gafni A, Sanders K, Mirsky D, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA 2004;292:435-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joynt KE, Blumenthal DM, Orav EJ, Resnic FS, Jha AK. Association of public reporting for percutaneous coronary intervention with utilization and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2012;308:1460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med 1997;127(8 Pt 2):666-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodham BL, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Evidence to support the use of laparoscopic over open appendicectomy for obese individuals: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 2012;26:2566-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Southgate E, Vousden N, Karthikesalingam A, Markar SR, Black S, Zaidi A. Laparoscopic vs open appendectomy in older patients. Arch Surg 2012;147:557-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hardiman K, Chang ET, Diggs BS, Lu KC. Laparoscopic colectomy reduces morbidity and mortality in obese patients. Surg Endosc 2013; published online 23 Feb. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Anania G, Scagliarini L, Santini M, Marzetti A, Gregorio C, Vedana L, et al. Benefits of laparoscopic colorectal surgery in the geriatric patient. G Chir 2012;33:352-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy for elderly patients with early-stage cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:195.e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo W, Bourdel N, Marengo F, Botchorishvili R, Pouly JL, Jardon K, et al. What’s the impact of the obesity on the safety of laparoscopic hysterectomy techniques? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2012;22:949-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]