Abstract

Resveratrol (5-[(E)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]benzene-1,3-diol), a redox active phytoalexin with a large number of beneficial activities is also known for antibacterial property. However the mechanism of action of resveratrol against bacteria remains unknown. Due to its extensive redox property it was envisaged if reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by resveratrol could be a reason behind its antibacterial activity. Employing Escherichia coli as a model organism we have evaluated the role of diffusible reactive oxygen species in the events leading to inhibition of this organism by resveratrol. Evidence for the role of ROS in E. coli treated with resveratrol was investigated by direct quantification of ROS by flow cytometry, supplementation with ROS scavengers, depletion of intracellular glutathione, employing mutants devoid of enzymatic antioxidant defences, induction of adaptive response prior to resveratrol challenge and monitoring oxidative stress response elements oxyR, soxS and soxR upon resveratrol treatment. Resveratrol treatment did not result in scavengable ROS generation in E. coli cells. However, evidence towards membrane damage was obtained by potassium leakage (atomic absorption spectrometry) and propidium iodide uptake (flow cytometry and microscopy) as an early event. Based on the comprehensive evidences this study concludes for the first time the antibacterial property of resveratrol against E. coli does not progress via the diffusible ROS but is mediated by site-specific oxidative damage to the cell membrane as the primary event.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Antibacterial, Antioxidant deficient mutants, Adaptive response

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Resveratrol possesses antibacterial property among a myriad of properties.

-

•

However the reasons behind its antibacterial property remains poorly understood.

-

•

We investigated the role of its redox property against the bacterium Escherichia coli.

-

•

We reveal the process is free of diffusible reactive oxygen species (ROS).

-

•

The initial event encompasses membrane damage.

Introduction

In the present day scenario it is absolutely vital to discover novel antibacterial molecules as antibiotic discovery process has not been able to keep the pace with rapidly emerging pathogens and drug resistant isolates [1]. In this process due emphasis is given to understand the mechanisms underlying the antibacterial action of the potential molecules. This helps in identifying the likely targets and predicts possible outcomes of resistant mechanisms that bacteria may develop. Resveratrol is a redox active molecule that readily binds with transition metal ion copper and reduces it. In this process it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) [2]. ROS can damage vital molecules inside a cell like DNA, proteins and membranes. It also alters the redox status inside a cell leading to pleiotropic effects that could culminate in cell death. Previous studies have shown that resveratrol and its metabolite piceatannol bind copper ions, generate ROS and damage DNA [2,3]. Inhibition of ROS generation by addition of chelators or scavenging ROS by antioxidants prevented this damage [2]. It has been further demonstrated that due to increased availability of copper in certain target cells, polyphenols like resveratrol are able to target them selectively [3].

Resveratrol inhibits a wide array of bacteria including both gram positive and gram negative organisms. It is more effective against gram positive bacteria than gram negative bacteria [4]. in vitro resveratrol inhibits Heliobacter pyroli that is responsible for chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer [5]. In rats fed with resveratrol prior to colitis induction, increase in the favourable lactobacilli and bifidobacteria was observed with a concomitant decrease in enterobacteria [6]. In spite of these observations the mechanism(s) behind resveratrol induced inhibition of bacteria remains unknown. The present study aims to understand the antibacterial action of resveratrol. In particular, we sought to probe any role of ROS, as resveratrol is a known ROS inducer. For this we employed a comprehensive array of biochemical and genetic approaches. Our results provided convincing evidence against the direct involvement of diffusible ROS in the resveratrol-mediated inhibition of Escherichia coli cells while the inhibition is a consequence of oxidative membrane damage.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) or plated on LB agar. The sodA sodB double mutant (designated NJ03) of strain MG1655 was constructed by P1-mediated transduction as previously described [7]. In brief sodA sodB double mutant NJ03 was generated by transduction of sodA allele from strain NJ01 mutant to NJ02 background [8].

Table 1.

List of the bacterial strains used in the study.

| Escherichia coli K-12 strain | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| MG1655 (wild type parent) | F ˉ λ ˉ rph-1 | E. coli Genetic Stock Center |

| JI367 | MG1655 katG17::Tn10Δ(katG17::Tn10)1 (Tets) katE12::Tn10 | James Imlay [14] |

| JI372 | MG1655 katE12::Tn10Δ(katE12::Tn10)1 (Tet s)Δ ahpCF' kan::'ahpF | James Imlay [14] |

| JI374 | MG1655 katG17::Tn10Δ(katG17::Tn10)1 (Tets) ahpCF' kan::'ahpF | James Imlay [14] |

| JI377 | MG1655 katG17::Tn10Δ(katG17::Tn10)1 katE12::Tn10Δ ahpCF' kan::'ahpF | James Imlay [14] |

| NJ03 | MG1655 sodA CamR, sodB KanR | This study |

| Clone 1179 | MG1655/pMS201 soxR-GFP | Thermo Scientific [10] |

| Clone 484 | MG1655/pMS201 soxS-GFP | Thermo Scientific [10] |

| Clone 1863 | MG1655/pMS201 oxyR-GFP | Thermo Scientific [10] |

Reagents and chemicals

The Luria agar components yeast extract, tryptone and agar were from Difco laboratories, USA. Tert-butyl hydroperoxide was purchased from Lancaster Synthesis, Morecambe, England. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was from Merck Specialities Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. L-Buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO), dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA), dimehtyl sulfoxide (DMSO), GSH, Lysozyme, Mitomycin C, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), Propidium iodide (PI) and Paraquat dichloride were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, USA. Live/Dead BacLight bacterial staining kit was from Molecular probes, Eugene, USA.

Enumeration of viable cells

Overnight E. coli cultures were diluted (1:100) in LB and grown afresh at 37 °C. Mid-exponential-phase culture (OD600 0.3–0.5) was exposed to different concentrations of resveratrol for 5 h at 37 °C. All the resveratrol treated samples contained a uniform concentration of vehicle (1% v/v DMSO). At the end of the incubation period the number of cells in each experimental tube was estimated by plating appropriate dilution on Luria agar plates. Whenever the effect of a particular supplementation had to be tested on resveratrol induced inhibition it was added in LB prior to the addition of resveratrol. To deplete intracellular GSH E. coli cells in LB were incubated with different concentrations of BSO overnight. The following morning the culture was diluted to 1 × 105 cfu/mL in fresh LB and challenged with resveratrol. To achieve oxygen depleted conditions the growth medium LB was purged with nitrogen for 30 min following which the experiment was set up immediately. The experimental tubes were sealed with Parafilm and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The plating was carried out in duplicate and experiments repeated thrice. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before counting the colonies. The data is represented in terms of percent survival. The counts corresponding to the number of bacteria on Luria agar without resveratrol were taken as 100% survival for the respective culture.

Quantification of ROS by flow cytometry

Mid-exponential-phase culture was exposed to different concentrations of resveratrol. At the end of the incubation period the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), incubated in PBS with 10 µM DCFDA in dark for 30 min. The cells were acquired by a flow cytometer (CyFlow Space, Partec, Germany) and fluorescence (excitation 488 nm and emission 530 nm) quantified.

Induction of adaptive response in E. coli

Mid-exponential-phase cells were suspended in saline with 1% glucose and exposed to H2O2 or γ-radiation to induce an adaptive response in E. coli. In case of H2O2 the cells were exposed to 0.5 mM H2O2 or 1 mM H2O2 for 30 min. In case of γ-radiation the cells were exposed to 10 Gy at a dose rate of 2.14 Gy/min and remained to stand till 30 min. At the end of 30 min cultures were treated with resveratrol for 5 h in LB and the number of viable cells was enumerated by plating on Luria agar.

Estimation of catalase in E. coli

The E. coli cells were lysed by treatment with lysozyme followed by sonication. The cell lysate was obtained by centrifugation at 4 °C for 30 min at 16,500 g. The amount of catalase per unit protein was estimated spectrophotometrically by a previously established method [9].

Monitoring expression of oxidative stress responsive genes

To monitor the expression of different genes in response to resveratrol, we employed the corresponding reporter strains from Thermo Scientific E. coli promoter collection which employs the E. coli K12 strain MG1655 wherein the promoters of corresponding genes are transcriptionally fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP) on a low copy plasmid pMS201 [10]. The fluorescence of GFP serves as a reporter for transcription initiation from the promoter. The cells were treated with resveratrol or respective positive control in 0.3 mL volume in a 96 well plate in triplicates. The plate was read at a 37 °C in a multiwell plate reader (Tecan Infine M200) up to 22 h. The GFP fluorescence (excitation: 480 nm and emission: 510 nm) and the absorbance (OD600) were quantified at 30 min intervals. Specific fluorescence intensities (SFI) were calculated by dividing fluorescence values by OD600 for the respective wells. Being a relatively stable protein, the accumulation of GFP fluorescence per cell (SFI) with respect to time gives an indication of the promoter activity. The strains employed from the collection for this study are serial numbers: 1862 oxyR (transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress, regulates intracellular H2O2 [LysR family]), 484 soxS (transcriptional activator of superoxide response regulon [AraC/XylS family]) and 1179 soxR (soxR transcriptional dual regulator).

Membrane compromise studies

Membrane compromise in E. coli was studied by quantifying the leaked potassium ions in the supernate as well as the residual potassium ions in the pellet. The cells were treated with vehicle or resveratrol in a 1 mL volume in PBS. After different time intervals the supernate and pellet were separated by centrifugation. The pellet was digested with 4 N nitric acid overnight. The samples were diluted with Nanopure water to 5 mL and the potassium was quantified by atomic absorption spectrometry. Membrane compromise (up to 3 h) was also studied by staining with Live/Dead BacLight kit followed by fluorescent microscopy according to the manufacturer׳s instructions. Pictures were acquired in a Carl Zeiss Axioskop2 Motplus fluorescent microscope. The SYTO–PI ratio was quantified spectrofluorimetrically (JASCO FP6500). The excitation and emission wavelengths for SYTO were 480 and 530 nm respectively and those of PI were 480 and 630 nm. To further quantify the membrane damage by the uptake of PI the test samples were treated with PI (50 µM) for 5 min in dark and acquired immediately by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±SE. Statistical differences between groups were calculated by the Student׳s unpaired t-test. p≤0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

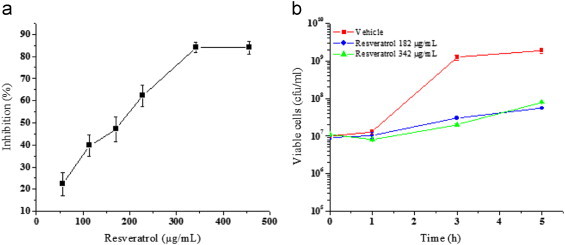

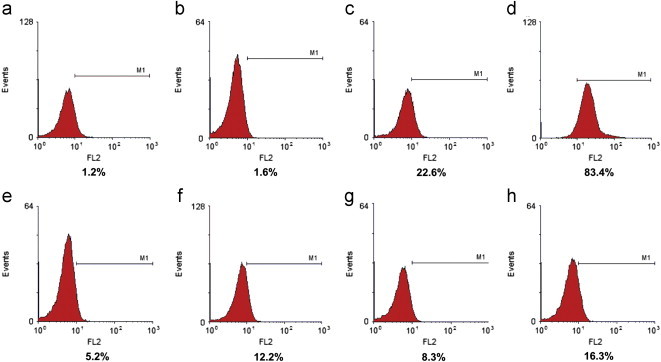

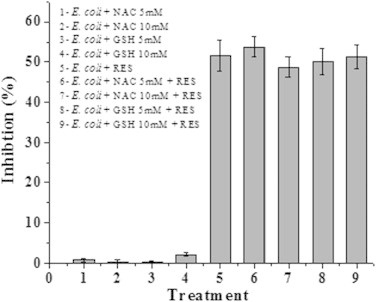

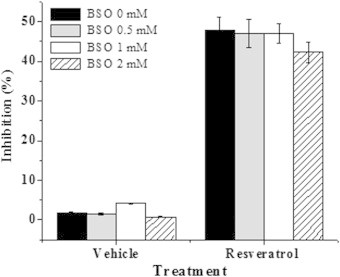

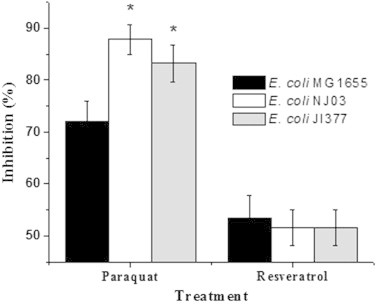

The effect of resveratrol on E. coli MG1655 was evaluated by exposing the cells in LB to increasing concentrations of resveratrol (57–456 µg/mL; 250–2000 µM). It was found that resveratrol inhibits growth of E. coli in a concentration dependent manner up to 342 µg/mL (Fig. 1a). The IC50 concentration was found to be 182.5±5.09 µg/mL. This value is in agreement with a previous report of related gram negative organisms albeit using a higher DMSO concentration that influences the solubility of resveratrol and subsequently its efficacy [11]. Further, the minimum inhibitory concentration of resveratrol against many gram negative microorganisms has been reported to be greater than 400 µg/mL [12]. This is due the insolubility of resveratrol beyond 400 µg/mL in aqueous media as observed by us and others [12]. Hence we employed IC50 as an end point in our studies. To evaluate if resveratrol is bactericidal or bacteriostatic we incubated pre-grown E. coli cells with resveratrol and monitored the number of viable cells at regular time intervals by plating. The results of both time and dose dependent experiments did not show any reduction in the number of viable cells due to resveratrol treatment, suggesting its bacteriostatic, but not bactericidal (Fig. 1b). The dose-dependent effect of resveratrol and the positive control H2O2 on ROS generation was evaluated at 2 h by flow cytometry using DCFDA as the oxidative probe. Compared to the control and vehicle-treated cells, resveratrol dose-dependently increased the DCFDA fluorescence, showing the maximum (16.3±2.8% increase) with resveratrol (228 µg/mL). The positive control, H2O2 (1 mM) induced a robust fluorescence (>80% at 1 mM) in the cells under similar conditions (Fig. 2). Separate time-dependent (0, 1, 2 and 3 h) experiments with resveratrol (228 µg/mL) showed a gradual increase in the DCFDA fluorescence up to 2 h when the plateau value as above was attained. External supplementation of the antioxidants, by pre-treating the cells with NAC and GSH (each 5 and 10 mM) did not prevent the cell inhibition by resveratrol (182 µg/mL). The antioxidant supplemented population exhibited the same amount of inhibition (48.83±2.57% to 53.86±2.62%) as that of 182 µg/mL resveratrol (51.75±3.73%) treated cells. The antioxidants NAC and GSH alone did not alter the growth of E. coli (Fig. 3). In a reverse approach we employed BSO to deplete the intracellular antioxidant glutathione. As shown in Fig. 4 E. coli cells treated with BSO did not exhibit a hypersensitive phenotype to subsequent resveratrol treatment. The sensitivity of the 0.5, 1 and 2 mM BSO treated cells to resveratrol (182 µg/mL) were 47.35±3.65%, 47.68±2.54%, 42.32±2.64% respectively which was not significantly different than that of BSO untreated cells (47.82±3.26%). Further we employed antioxidant defence deficient E. coli strains to investigate the role of ROS upon treatment with resveratrol. Enzymatic antioxidant defences of E. coli against superoxide and peroxides comprises of superoxide dismutases (sodA, sodB and sodC), catalase (katG and katE) or alkaline hydroperoxidase (ahpCF) respectively [13,14]. The efficacy of resveratrol on these multiple knock out strains was compared to the wild type strain that had these defences intact. We employed mutants that lack more than one antioxidant defence in this investigation as lack of one gene product is compensated by the other and defeat the purpose of the investigation. All the three catalase and peroxidase double mutants (i.e. JI367, JI372 and JI374) exhibited similar sensitivity to 182 µg/mL resveratrol (49.23±4.26%, 51.60±3.56% and 53.81±4.62% respectively) as that of the wild type parent strain MG1655 (52.17±3.84%). Moreover the extent of inhibition seen with catalase (katE, katG) and alkylhydroperoxidase reductase (ahpCF) mutant JI377 (51.63±3.44%) was not different from the parent strain MG1655. Similarly NJ03 which is the double gene knockout for cytosolic superoxide dismutase activities (SodA and SodB) exhibited similar inhibition (51.60±3.47%) as compared to the wild type parent strain (53.51±4.33%) upon resveratrol treatment (182 µg/mL). However upon paraquat treatment (64 µg/mL), a drug that generates superoxide radicals this double mutant (87.82±2.94%) and the triple mutant JI377 (83.2±3.6%) exhibited significant increase in sensitivity compared to wild type (72.13±3.82%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

(a) Effect of resveratrol on the growth of E. coli. E. coli cells in LB treated with different concentrations of resveratrol for 5 h exhibited reduced growth as enumerated by viable count. (b) Effect of resveratrol on pre-grown E. coli cells. A bacteriostatic effect was observed on E. coli cells incubated with resveratrol. The number of cells in different samples was enumerated on Luria agar plates in a time dependent manner up to 5 h. The experiments were performed thrice with triplicate samples. The values denoted are mean±SEM.

Fig. 2.

Quantification of ROS upon treatment with resveratrol. After treatment with different concentrations of resveratrol for 2 h, the cells were analysed for ROS with DCFDA by flow cytometry. (a) Untreated, (b) vehicle, (c) 0.5 mM H2O2, (d) 1.0 mM H2O2, (e–h) resveratrol 57, 114, 171 and 228 µg/mL respectively. Values below the histograms represent the percent of cells positive for DCF fluorescence (FL2) as quantified by flow cytometry. The experiment was conducted thrice with triplicate samples. Each histogram is one representative sample.

Fig. 3.

Effect of antioxidants on resveratrol induced E. coli inhibition. E. coli cells pre-incubated with NAC and GSH were challenged with resveratrol (182 µg/mL). The number of viable cells was enumerated on Luria agar plates. The experiment was performed thrice with triplicate samples. The values denoted are mean±SEM. RES indicates resveratrol in the figure.

Fig. 4.

Effect of GSH depletor BSO on resveratrol induced bacterial inhibition. E. coli cells were treated overnight with different concentrations of BSO. These populations were challenged with resveratrol (182 µg/mL) and the extent of growth inhibition quantified by plating the cells on Luria agar. The experiment was performed thrice with triplicate samples. The values denoted are mean±SEM.

Fig. 5.

Effect of absence of superoxide dismutase and catalase on resveratrol induced E. coli inhibition. E. coli mutants NJ03 (sodA−sodB−) and JI377 (katG−katE−ahpCF−) were treated with paraquat (64 µg/mL) and resveratrol (182 µg/mL) to assess comparative sensitivity to that of wild type strain (E. coli MG1655). Paraquat was used as a control. The experiment was conducted thrice with triplicate samples. The values denoted are mean±SEM. *Data values are significantly different (p≤0.05).

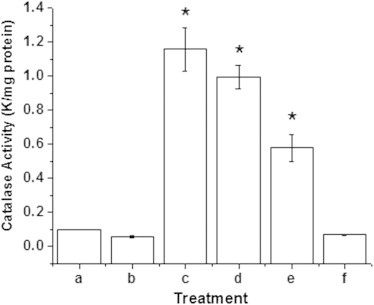

To gain further evidence, the E. coli cells were exposed to H2O2 or γ-radiation to induce adaptive oxidative stress response in them. Incubation of the cells for 30 min with different concentrations of H2O2 (0.5–10 mM) revealed that 0.5 mM H2O2 did not affect the cell viability, but 1 and 5 mM H2O2 reduced it by 4.36±1.34% and 26.78±2.36% respectively, compared to untreated sample. A similar dose-dependent study revealed that a γ-ray dose up to 10 Gy did not result in reduction in viability (data not shown). Hence H2O2 (0.5, 1 mM) or γ-radiation (dose 10 Gy) was used to investigate the effect resveratrol on adapted cells. The adaptive oxidative stress response in these cells was examined from the levels of catalase as a marker for enhanced antioxidant defence. The first order rate constant which is a measure of the quantity of catalase present in the sample is given in Fig. 6. The populations, exposed to H2O2 or γ-radiation exhibited an enhanced antioxidant defence status compared to the untreated cells (Fig. 6). Untreated and sham irradiated cells exhibited catalase concentrations 0.09±0.001 and 0.05±0.007 k/mg protein while 0.5 and 1 mM H2O2 treated cells exhibited 1.1±0.126 k/mg and 1.00±0.068 k/mg protein respectively, a tenfold increase compared to untreated cells. A similar significant increase in catalase levels (0.58±0.782 k/mg protein) was observed upon exposure to 10 Gy γ-radiation. Resveratrol itself did not alter the catalase levels in E. coli. However, none of these adaptively-primed cells showed any significant change in their sensitivity to resveratrol (182 µg/mL). It was anticipated that any molecule that act via a ROS pathway lose its efficacy under oxygen depleted conditions. Under oxygen depleted conditions the inhibitory property of resveratrol towards E. coli remained unaltered compared to the experiment carried out at ambient oxygen level (IC50≈182 µg/mL in both cases).

Fig. 6.

Quantification of adaptive oxidative stress response in E. coli. The levels of catalase in E. coli treated with non-lethal doses of H2O2 and γ-radiation was quantified spectrophotometrically. (a) Untreated cells, (b) sham irradiated cells, (c) 0.5 mM H2O2 treated cells, (d) 1 mM H2O2 treated cells (e) 10 Gy γ-irradiated cells and (f) resveratrol (182 µg/mL). The experiment was conducted thrice with triplicate samples. The values denoted are mean±SEM. *Indicates the data values are significantly different from samples (a) and (b) (p≤0.05).

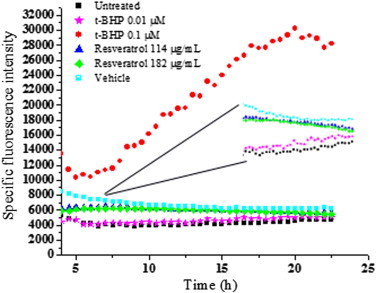

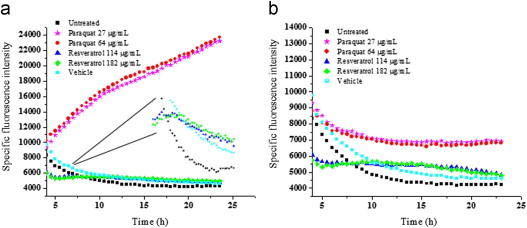

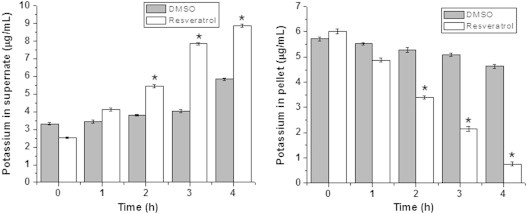

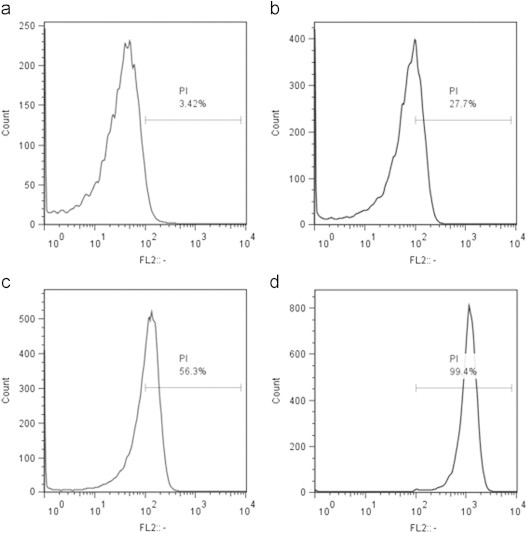

Finally to investigate the role of ROS in resveratrol mediated bacterial inhibition we looked into the expression of sensor/regulatory proteins that are sensitive to oxidative stress. In E. coli oxyR regulon is reported to be induced upon exposure to the peroxide stress whereas soxRS is induced by superoxide radicals [15]. Treatment with resveratrol did not induce oxyR, soxS or soxR genes significantly, as observed from the green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence of the respective GFP-tagged genes (Figs. 7 and 8). However a robust induction was seen in case of oxyR when treated with tert-butyl hydroperoxide (Fig. 7). Similarly paraquat treatment induced the soxS significantly (Fig. 8a), although the increase of soxR was not pronounced (Fig. 8b). Resveratrol treated samples exhibited membrane damage as evidenced by the leakage of potassium in the supernate and a corresponding decrease in the pellet (Fig. 9). In resveratrol treated cells the amount of potassium increased in supernate from 2.54 µg/mL at 0 h to 8.88 µg/mL at 4 h. The decrease in potassium quantity in the pellet was found to be 0.76 µg/mL at 4 h from 6.02 µg/mL at 0 h. In case of vehicle treated cells such a change was not observed. This was further confirmed by fluorescent microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Quantification of SYTO–PI ratio revealed decrease in the ratio in a concentration dependent manner in resveratrol treated samples but not in mitomycin C treated samples (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Further flow cytometry analysis revealed a marked uptake of PI in resveratrol treated cells (Fig. 10) which indicated membrane compromise. Cells treated with 70% isopropyl alcohol (membrane permeablized cells) were used as positive control.

Fig. 7.

Effect of resveratrol on expression of oxyR regulon in E. coli. E. coli with oxyR-GFP construct was treated with resveratrol and the expression was followed fluorimetrically. tert-butyl hydroperoxide was used as a positive control to induce the oxyR regulon. Filled squares indicate untreated cells, half filled squares indicate vehicle treated cells, stars indicate cells treated with 0.01 µM tert-butyl hydroperoxide, circles indicate cells treated with 0.1 µM tert-butyl hydroperoxide, triangles indicate cells treated with 114 µg/mL resveratrol and diamonds indicate cells treated with 182 µg/mL resveratrol. The inset shows the magnification of the closely placed data points. The values are mean of triplicates of a single experiment. The experiment was performed twice.

Fig. 8.

Effect of resveratrol on expression of (a) soxS and (b) soxR in E. coli. E. coli with soxS-GFP or soxR-GFP construct was treated with resveratrol and the expression was followed fluorimetrically. Paraquat was used as a positive control. Filled squares indicate untreated cells, half filled squares indicate vehicle treated cells, stars indicate cells treated with 27 µg/mL paraquat, circles indicate cells treated with 64 µg/mL paraquat, triangles indicate cells treated with 114 µg/mL resveratrol and diamonds indicate cells treated with 182 g/mL resveratrol. The inset shows the magnification of the closely placed data points. The values are mean of triplicates of a single experiment. The experiment was performed twice.

Fig. 9.

Membrane damage induced by resveratrol quantified by potassium release. E. coli cells treated with resveratrol (182 µg/mL) analysed for potassium in pellet and supernate by atomic absorption spectrometry. The values denoted are mean±SEM. *Values are significantly different compared to 0 h values (p≤0.05).

Fig. 10.

Propidium iodide uptake by flow cytometry. Uptake of the membrane impermeable dye PI was quantified by flowcytometry in (a) untreated cells (b) vehicle treated cells (c) resveratrol (182 µg/mL) treated cells (3 h) and (d) membrane permeabilized cells. The values are typical of a single sample. The experiment was performed twice in triplicate.

Discussion

Plant polyphenols are important components of human diet and a number of them are considered to possess chemopreventive and therapeutic properties. A redox reaction of the polyphenols and Cu(II) in the ternary complex may occur leading to the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I), whose reoxidation generates a variety of ROS [2]. This has been attributed as a primary reason behind the cytotoxic potential of several polyphenols including resveratrol [16,17]. Extensive work has been carried out on the health benefits of resveratrol and the associated mechanism of its action [18]. Its antibacterial activity has also previously been reported [11,19]. Kohanski et al. have proposed a unified common mechanism of killing bacteria by antibiotics, involving induction of the most reactive ROS, hydroxyl radicals [20]. Several antibacterial molecules have been suggested to act via this ROS generation pathway [8,21]. In view of these, the role of oxidative stress in the antibacterial activity of resveratrol was examined for the first time in this study. Direct quantification of ROS by different fluorescent dyes has been a useful technique to demonstrate the involvement of ROS in a process. This in conjunction with external supplementation of antioxidants to scavenge the ROS provides valuable insight in to the events leading to macromolecular damage and cellular cytotoxicity. Fluorescence augmentation due to oxidation of DCFDA by ROS has been employed previously in E. coli to elucidate the role of ROS [22]. ROS generated by antibiotics when scavenged by externally supplemented antioxidants result in loss of their efficacy against the target bacteria [8]. This has been widely employed to evaluate the role of ROS in different antibiotics. In case of ciprofloxacin, NAC and GSH gave greater than 90% protection to E. coli cells [8]. BSO, an irreversible inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase, has been used to inhibit GSH synthesis. BSO by depletion of intracellular GSH enhanced the susceptibility of trypanosomes to Megazol [23]. In our investigation we did not observe significant ROS by the DCFDA method. This coupled with failure of external antioxidants to protect E. coli against resveratrol and failure of BSO to hypersensitize E. coli to resveratrol strongly indicated non-involvement of ROS. Antioxidant enzymes, catalase, alkylhydroperoxide reductase and superoxide dismutase form a critical defence against endogenous ROS generation in cells as well as exogenous means like drug treatment, radiation etc. Absence of these enzymes has been shown to render the cells susceptible to oxidative stress [14]. To obtain further proof towards the role of ROS in resveratrol mediated antibacterial activity we employed mutants lacking these key antioxidant defences. Unlike H2O2, resveratrol treatment did not induce a hypersensitive phenotype in E. coli cells lacking catalase and alkyl hydroperoxide reductase. Similar result was obtained in case of superoxide dismutase double mutant upon treatment with resveratrol. As observed by others [13] we too found the double mutant of superoxide dismutase to be hypersensitive to paraquat.

Oxidative stress is believed to be an important factor contributing towards adaptive response by inducing the enzymatic and non-enzymatic defences in a cell. The adaptive response is a nonspecific response of a cell in which exposure to minimal stress could result in increased resistance to higher levels of the same or other types of stress few hours later. Demple and Halbrook first showed that E. coli treated with low doses of H2O2 becomes resistant to subsequent lethal doses of the same [24]. Exposure to H2O2 or γ-radiation is known to induce oxidative stress. We induced an adaptive oxidative stress response in E. coli after exposure to non-lethal concentration of H2O2 and γ-radiation evident by several fold increase in catalase. Earlier such response negated subsequent toxicity induced by a variety of aldehyde compounds in E. coli [25]. Similarly H2O2 pre-treatment also protected E. coli cells against methylnitronitrosoguanidine induced lethality which is known to progress by ROS generation [26]. But in the current investigation the adaptive oxidative stress response did not aid E. coli cells in combating a subsequent resveratrol challenge.

Many of the oxidative stress induced genes are under the control of OxyR in E. coli. Mutants that lack oxyR are hypersensitive to H2O2 and many oxidants. The spontaneous mutation rate is also elevated in these mutants under aerobic conditions [27]. Similarly soxSR regulon control the expression of at least 10 proteins that are induced upon exposure to superoxide generating agents. Under oxidative stress a conformational change occurs in soxR that acts as a transcriptional activator of soxS. The SoxS protein then activates the transcription of genes that are under the control of soxSR [28]. Although induction of oxyR by tert-butyl hydroperoxide and induction of soxSR by paraquat was observed as a proof of principle in our experiments, resveratrol did not induce the expression of oxyR or soxSR. This provided further evidence of lack of any oxidative stress in the E. coli cells due to resveratrol treatment. Previous studies in case of clofazimine, a riminophenazone antibiotic active against Mycobacterium it was found that ROS scavengers could not prevent the inhibitory activity of this antibiotic in spite of it being a potential candidate for intracellular redox cycling. The outer membrane appeared to be the primary site of action of this antibiotic [29]. We also found membrane damage after treatment with resveratrol in E. coli proved by potassium leakage, SYTO–PI dual staining and PI uptake by flow cytometry. However it is not clear at this point how it is taking place. Although diffusiable/scavengable ROS could not be detected, the damage might still be occurring by oxidation where in the transfer of electrons between the target and the oxidizer could be occurring in a very short time frame and in a microenvironment not amenable to the detection techniques employed in this investigation. Membrane damage could also occur due to activation of certain phospholipases in the cell. It has also been observed that resveratrol inhibits purified as well as membrane bound F1 ATP synthase [30,31]. Since ATP synthase is an important drug target [31], it would be interesting to investigate the link between this and membrane damage. ATP synthase is regulated in response to proton motive force to avoid wasteful ATP hydrolysis. Though it has been showed resveratrol binds to ATP synthase and inhibits it, the inhibition of the same might also be due to loss of proton motive force induced by the membrane damage by resveratrol. Our result also throws up an interesting avenue as it has been reported previously certain organic molecules aid in increasing the efficacy of existing antibiotics that may be ineffective due to the outer membrane architecture of gram negative bacteria [32,33]. Since resveratrol changes the membrane permeability of E. coli it would be interesting to see if this property aids in the efficacy of other drugs used against E. coli in particular or gram negative bacteria in general. Further detailed experimentation could reveal if co-treatment or pre-treatment with resveratrol would aid some of the standard drugs to be more potent thereby producing a favourable clinical outcome. The bactericidal antibiotics are hypothesized to generate ROS and kill the target bacteria. A few examples were investigated and evidence towards this hypothesis was gathered [20]. Our results also corroborate this, as we found resveratrol to be bacteriostatic and not bactericidal. Taken together, our data strongly suggests that unlike certain other antibacterials [8] scavengable ROS generation and subsequent oxidative stress do not play an obligatory role in the resveratrol-mediated inhibition of E. coli cells. However we find the primary event in resveratrol mediated inhibition of E. coli is membrane damage. Further investigation is currently underway towards the mechanism behind membrane damage, direct damage or activation of phospholipases and damage of any secondary targets inside the cells.

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Funding

The study is funded by internal department funds of Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to James Imlay (University of Illinois) for providing the strains related to this study. The author M.S. wishes to express his gratitude to Dr. S. Chattopadhyay for his keen interest, support and critical reading of the manuscript.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Supplementary Fig. 1.

(a) Membrane damage induced by resveratrol. E. coli treated with vehicle or resveratrol (182 µg/mL) or mitomycin C (1 µg/mL) was stained with SYTO and propidium iodide. The uptake of the dyes was observed under a fluorescent microscope. (b) Quantification of SYTO/PI ratio spectrofluorimetrically in cells treated with resveratrol or mitomycin C at the end of 3 h. Ratio of SYTO/PI in (i) untreated cells, (ii) resveratrol (182 µg/mL), (iii) resveratrol (342 µg/mL), (iv) mitomycin C (0.5 µg/mL) and (v) mitomycin C (1 µg/mL). The values denoted are mean±SEM. *Data values are significantly different (p≤0.05) compared to untreated cells.

References

- 1.Fischbach M.A., Walsh C.T. Antibiotics for emerging pathogens. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2009;325:1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1176667. 19713519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subramanian M., Shadakshari U., Chattopadhyay S. A mechanistic study on the nuclease activities of some hydroxystilbenes. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;12:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.10.062. 14980635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z., Yang X., Dong S., Li X. DNA breakage induced by piceatannol and copper(II): mechanism and anticancer properties. Oncology Letters. 2012;3:1087–1094. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.597. 22783397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paulo L., Ferreira S., Gallardo E., Queiroz J.A., Domingues F. Antimicrobial activity and effects of resveratrol on human pathogenic bacteria. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;26:1533–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulo L., Oleastro M., Gallardo E., Queiroz J.A., Domingues F. Anti-Helicobacter pylori and urease inhibitory activities of resveratrol and red wine. Food Research International. 2011;44:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larrosa M., Yañéz-Gascón M.J., Selma M.V., González-Sarrías A., Toti S., Cerón J.J., Tomás-Barberán F., Dolara P., Espín J.C. Effect of a low dose of dietary resveratrol on colon microbiota, inflammation and tissue damage in a DSS-induced colitis rat model. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2009;57:2211–2220. doi: 10.1021/jf803638d. 19228061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller J.H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goswami M., Mangoli S.H., Jawali N. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2006;50:949–954. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.949-954.2006. 16495256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aebi, H. E., 1986: Catalase in: Bergmeyer, H. U (Ed.): Methods of enzymatic analysis, 3. Edition, Band 3, VCH Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, Weinheim, 273–286

- 10.Zaslaver A., Bren A., Ronen M., Itzkovitz S., Kikoin I., Shavit S., Liebermeister W., Surette M.G., Alon U. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nature Methods. 2006;3:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. 16862137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan M.M. Antimicrobial effect of resveratrol on dermatophytes and bacterial pathogens of the skin. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;63:99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00886-3. 11841782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulo L., Ferreira S., Gallardo E., Queiroz J.A., Domingues F. Antimicrobial activity and effects of resveratrol on human pathogenic bacteria. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;26:1533–1538. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassett D.J., Schweizer H.P., Ohman D.E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB mutants defective in manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase activity demonstrate the importance of the iron-cofactored form in aerobic metabolism. Journal of Bacteriology. 1995;177:6330–6337. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6330-6337.1995. 7592406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seaver L.C., Imlay J.A. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183:7173–7181. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7173-7181.2001. 11717276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng M., Doan B., Schneider T.D., Storz G. OxyR and SoxRS regulation of fur. Journal of Bacteriology. 1999;181:4639–4643. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4639-4643.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadi S.M., Ullah M.F., Azmi A.S., Ahmad A., Shamim U., Zubair H., Khan H.Y. Resveratrol mobilizes endogenous copper in human peripheral lymphocytes leading to oxidative DNA breakage: a putative mechanism for chemoprevention of cancer. Pharmaceutical Research. 2010;27:979–988. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0055-4. 20119749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z., Li W., Meng X., Jia B. Resveratrol induces gastric cancer cell apoptosis via reactive oxygen species, but independent of sirtuin1. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 2012;39:227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05660.x. 22211760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smoliga J.M., Baur J.A., Hausenblas H.A. Resveratrol and health—a comprehensive review of human clinical trials. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2011;55:1129–1141. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100143. 21688389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S.K., Lee H.J., Min H.Y., Park E.J., Lee K.M., Ahn Y.H., Cho Y.J., Pyee J.H. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of pinosylvin, a constituent of pine. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:258–260. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2004.12.004. 15752644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohanski M.A., Dwyer D.J., Hayete B., Lawrence C.A., Collins J.J. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell. 2007;130:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.049. 17803904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goswami M., Jawali N. N-acetylcysteine-mediated modulation of bacterial antibiotic susceptibility. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54:3529–3530. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00710-10. 20547812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzgerald M.P., Madsen J.M., Coleman M.C., Teoh M.L., Westphal S.G., Spitz D.R., Radi R., Domann F.E. Transgenic biosynthesis of trypanothione protects Escherichia coli from radiation-induced toxicity. Radiation Research. 2010;174:290–296. doi: 10.1667/RR2235.1. 20726720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enanga B., Ariyanayagam M.R., Stewart M.L., Barrett M.P. Activity of megazol, a trypanocidal nitroimidazole, is associated with DNA damage. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2003;47:3368–3370. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3368-3370.2003. 14506061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demple B., Halbrook J. Inducible repair of oxidative DNA damage in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1983;304:466–468. doi: 10.1038/304466a0. 6348554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunoshiba T., Hashimoto M., Nishioka H. Cross-adaptive response in Escherichia coli caused by pretreatment with H₂O₂ against formaldehyde and other aldehyde compounds. Mutation Research. 1991;255:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90030-s. 1719398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asad L.M., Asad N.R., Silva A.B., Felzenszwalb I., Leitão A.C. Hydrogen peroxide induces protection against N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) effects in Escherichia coli. Mutation Research. 1997;383:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(96)00053-5. 9088346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storz G., Tartaglia L.A. OxyR: a regulator of antioxidant genes. Journal of Nutrition. 1992;122:627–630. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.suppl_3.627. 1542022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Membrillo-Hernández J., Kim S.O., Cook G.M., Poole R.K. Paraquat regulation of hmp (flavohemoglobin) gene expression in Escherichia coli K-12 is SoxRS independent but modulated by sigma S. Journal of Bacteriology. 1997;179:3164–3170. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3164-3170.1997. 9150210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cholo M.C., Steel H.C., Fourie P.B., Germishuizen W.A., Anderson R. Clofazimine: current status and future prospects. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67:290–298. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr444. 22020137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad Z., Ahmad M., Okafor F., Jones J., Abunameh A., Cheniya R.P., Kady I.O. Effect of structural modulation of polyphenolic compounds on the inhibition of Escherichia coli ATP synthase. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2012;50:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.01.019. 22285988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dadi P.K., Ahmad M., Ahmad Z. Inhibition of ATPase activity of Escherichia coli ATP synthase by polyphenols. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2009;45:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.04.004. 19375450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chevalier J., Mahamoud A., Baitiche M., Adam E., Viveiros M., Smarandache A., Militaru A., Pascu M.L., Amaral L., Pagès J.M. Quinazoline derivatives are efficient chemosensitizers of antibiotic activity in Enterobacter aerogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant strains. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2010;36:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.03.027. 20494558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martins M., Dastidar S.G., Fanning S., Kristiansen J.E., Molnar J., Pagès J.M., Schelz Z., Spengler G., Viveiros M., Amaral L. Potential role of non-antibiotics (helper compounds) in the treatment of multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections: mechanisms for their direct and indirect activities. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2008;31:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.10.025. 18180147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]