Abstract

AIM: To heighten recognition of primary pancreatic lymphoma (PPL) in clinical practice.

METHODS: A retrospective review of the clinical presentation, imaging characteristics and pathological features of PPL patients were presented, as well as their diagnosis and treatment, in combination with literature review.

RESULTS: Histological diagnosis was made in four patients by surgery and in two patients by EUS-FNA. The six PPL patients (5 males and 1 female; age range, 16-65 years; mean age, 46 years) had the duration of symptoms for two weeks to three months. The primary presenting symptoms, though not characteristic, were abdominal pain, abdominal masses, weight loss, jaundice, nausea and vomiting. One of the patients developed acute pancreatitis. In one patient, the level of serum CA19-9 was 76.3 μg/L. Abdominal CT scan showed that three of the six tumors were located in the head of pancreas, two in the body and tail, and one throughout the pancreas. Diameter of the tumors in the pancreas in four cases was more than 6 cm, with homogeneous density and unclear borders. Enhanced CT scan showed that only the tumor edges were slightly enhanced. The pancreatic duct was irregularly narrowed in two cases whose tumors were located in the pancreatic head and body, in which endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed that the proximal segment was slightly dilated. Two patients underwent Whipple operation, one patient underwent pancreatectomy, and another patient underwent operative biliary decompression. PPL was in stageIE in 2 patients and in stage II E in 4 patients according to the Ann Arbor classification system. The diagnosis of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma was made in all patients histopathologically. All six patients underwent systemic chemotherapy, one of whom was also treated with gamma radiometry. One patient died two weeks after diagnosis, two patients lost follow-up, two patients who received chemotherapy survived 49 and 37 mo, and the remaining patient is still alive 21 mo, after diagnosis and treatment.

CONCLUSION: PPL is a rare form of extranodal lymphoma originating from the pancreatic parenchyma. Clinical and imaging findings are otherwise not specific in the differentiation of pancreatic lymphoma and pancreatic cancer, which deserves attention. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of the pancreas requires experienced cytopathologists as well as advanced immunohistochemical assays to obtain a final diagnosis on a small amount of tissue. Surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy can produce fairly good outcomes.

Keywords: Pancreatic malignant tumor, Lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Lymphoma includes Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s forms. Hodgkin’s lymphomas rarely disseminate to extra-lymphatic organs, while non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas often invade extra-lymphatic organs. Most primary pancreatic lymphomas (PPL) are non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. More than 25 percent of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas originate from extra-lymphatic organs, about 30 percent of which may involve the pancreas[1] . Isolated PPL is quite rare, less than 1 percent[2]. In a review of 207 cases of malignant pancreatic tumors, there were only three cases (1.5%) of pancreatic lymphoma[3]. In fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of 1050 cases of pancreatic lesions, Volmar et al[4] only found 14 cases (1.3%) of PPL. Clinically, PPL is most likely to be misdiagnosed as pancreatic cancer. The present article is a retrospective review of six cases of PPL, based on which the clinical presentation, imageologic characteristics and pathologic features of PPL are discussed in the context of the world literature in an attempt to heighten clinicians’ awareness of the condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Six cases of PPL were identified and treated in Department of Gastroenterology, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China, during a 15-year period from January 1990 to June 2005. The clinical characteristics of all the patients were consistent with the criteria for the diagnosis of PPL defined by Behrns et al[1]. On physical examination, no enlarged superficial lymph nodes were found; no enlarged diaphragmatic lymph nodes on chest X-ray films were found either. There was no change of WBC classification on hemograms; there were no significant hepatic and splenic focuses. However, there was evidence of a pancreatic mass on laparotomy, and the lymph nodes involved were confined to areas around the pancreas.

Methods

A retrospective review of the clinical data revealed that malignant lymphoma was unanimously the initial diagnosis of all the six cases. Immunohistochemical analysis by EnVision-methods included leukocyte common antigen (LCA), CD20, CD34, CD68, Chr, CD45RO and Ki-67, of which LCA indicates that tumor cells come from lymphocytes, CD20 is the marker of B-cell, and CD45RO is the marker of T-cell.

All patients were staged according to the Ann Arbor staging system for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, stageI: invasion of lymphoma is confined to the pancreas; stage II: apart from pancreatic invasion, there is also invasion of local lymph nodes; stage III: apart from pancreatic invasion, the focus also infiltrates the upper diaphragm; and stage IV: apart from pancreatic invasion, there is generalized infiltration[5].

RESULTS

Clinical presentation

The six PPL patients included five males and one female who ranged in age from 16 to 65 years with a mean of 46 years, and whose duration of symptoms ranged from two weeks to three months. The primary presenting symptoms were abdominal pain, an abdominal mass, weight loss, jaundice, nausea and vomiting, which were similar to what were reported in the overseas literatures[6-9] , except that there were no lower back pain, fever and chill, ascites and hemorrhage of the upper digestive tract (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical presentation of PPL n (%)

| Data | This report | Overseas report[5] | Overseas CDI[9] |

| Case number | 6 | 11 | 85 |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (83) | 9 (82) | 62 (73) |

| Weight loss | 3 (50) | 4 (36) | 43 (51) |

| Abdominal mass | 2 (33) | - | - |

| Jaundice | 2 (33) | 2 (18) | 36 (42) |

| Nausea | 2 (33) | 2 (18) | 29 (34) |

| Vomiting | 1 (17) | - | 15 (18) |

| Lower backache | - | 3 (27) | - |

| Fever | - | 2 (18) | 6 (7) |

| Ascites | - | 1 (9 ) | - |

| Hemorrhage of UDT | - | - | 2 (2) |

CDI: Compositive details index; UDT: Upper digestive tract.

Laboratory and imaging findings

WBC count was within the normal range in all six cases. In four patients aspartate aminotransferase (ALT) was 80-265 U/L and alkaline phosphatase (AKP) was 120-216 U/L; in three patients, the level of serum bilirubin was 42-216 μmol/L and CA19-9 was 76.3 μg/L. Liver function was otherwise normal. Abdominal CT scan demonstrated that the tumor was located in the head of pancreas in three cases, in the body and tail in two cases, and in the whole pancreas in the remaining case. The tumors were larger than 6 cm in four cases, with almost homogeneous density and unclear edges. Enhanced CT scan only enhanced the edges slightly. ERCP in two cases revealed that the pancreatic duct at the body of the head was irregularly narrowed, the proximal segment of which was slightly dilated.

Histopathologic study

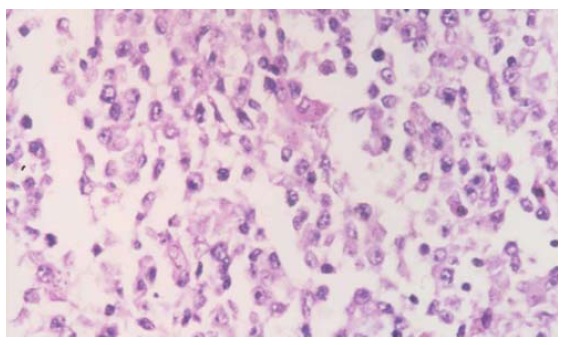

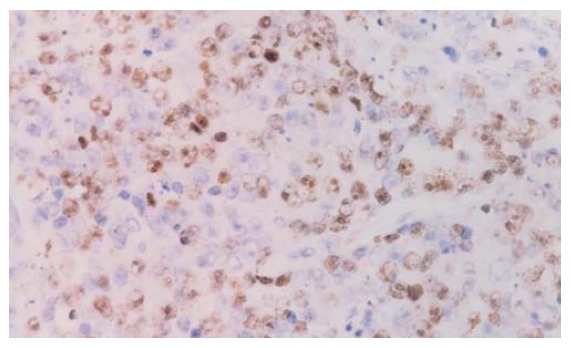

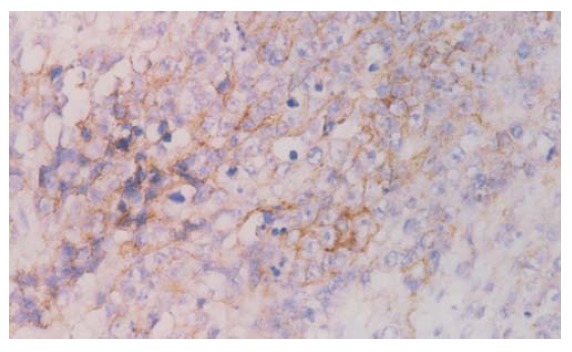

The specimens were obtained from pancreatic resection in fours cases, and from EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in the remaining two cases. Microscopic examination showed that the lymphoma cells were round or elliptic, and arranged diffusely, with little plasma, thick karyotheca, thick chromatin and clear nuclei. Immunohistochemical analysis showed LCA (+), CD20 (+), CD34 (-) and CD68 (-). Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of the six cases as B cell pancreatic lymphoma (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1.

Cytologically, lymphoma cells are round, oval, with prominent and large nucleus, arranged diffusely with obvious heterogeneity (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification × 200).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis showing Ki-67 (+) (EnVision’s stain; original magnification × 200).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical analysis showing CD20 (+) (EnVision's stain; original magnification × 200).

Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis

Of the six patients, diagnosis was confirmed by pathological study of the pancreatic tissue resected by EUS-FNA in two patients, by my cytological study in one patient, and by general skeleton ECT scan in another patient. One patient underwent biliary-intestinal anastomosis. According to Ann Arbor classification, two cases belonged to I E stage, and the remaining four cases to II E stage. All six patients underwent chemotherapy, one of whom also underwent linear accelerator radio-therapy, and another underwent stereotaxic γ-knife radiotherapy. One patient died two weeks after the diagnosis was confirmed; two patients were lost to follow-up; two patients survived for 49 and 37 mo, and the remaining one patient is still being followed up.

DISCUSSION

Primary pancreatic lymphoma(PPL) is an extremely rare disease which occurs in pancreatic situ, with or without involvement of peripancreatic lymph nodes. The clinical manifestation and imaging result of PPL resemble other pancreatic occupying lesions like pancreatic carcinoma. However, unlike carcinomas, PPLs are potentially treatable even if not found at early stage. PPL only accounts for fewer than 2% of extra-nodal malignant lymphomas and 0.5% of cases of pancreatic masses[10,11]. To date, only fewer than 150 and 20 cases of PPL have been reported in English literature[12] and Chinese medical literature, respectively. In China, from 1995 to 2003 there were totally 16 cases of PPL reported[13]. The data show a strong male predominance (male to female ratio of 13:3) and increased trend with age (median age of 57.5 years), which is similar to the present study. However whether the mean age of PPL is older than that of pancreatic carcinoma remains controversial.

Although the clinical presentation of PPL is varied, some findings may support PPL rather than pancreatic cancer. Bellyache and abdominal mass are two major symptoms which present in 83% and 58% of PPL cases, respectively[12]. Two of six of our patients (33%) presented abdominal mass while Yu et al reported that only 1.3% of patients with adenocarcinoma presented abdominal mass[14]. The other symptoms are jaundice, reflux, weight loss, bowel obstruction and diarrhea[6,15]. Interestingly there are almost 12% of PPL mimicking acute pancreatitis. It is noticeable that one in six of our patients presented acute pancreatitis. Obstructive jaundice was found to be less frequent than in pancreatic cancer[16]. While the common symptoms in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma like fever, chills and night sweats were rare in PPL, making it hard to diagnose only depending on the signs[17]. The majority PPLs occur in the head of pancreas, though tumor could also be found in the body and tail regions[7]. It was reported that over half of PPL patients presented with an epigastric mass and the diameter was bigger than 6 cm in 70% of patients of PPL[18]. The laboratory test is non-specific for diagnosis of PPL. Our data reveal that serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level in PPL patients was normal or slightly elevated. This is different from pancreatic adenocarcinoma, in which almost eighty percent of patients get a higher CA19-9 level. The abnormality of serum ALT, AKP, and bilirubin was secondary to the bile duct obstruction.

Imaging results play a key role in diagnosis of PPL. Percutaneous ultrasound(US), endoscopic ultrasonography(EUS), computed tomography(CT) and MRI are well-established procedures to evaluate pancreatic masses[19,20]. Previously 16 Chinese PPL cases could all be found pancreatic masses by CT or US before therapy, with or without signs of peripancreatic lymph node invasion. CT is by far the most common imaging technique used in the detection and characterization of pancreatic tumors. The picture of PPL on CT resembled that of pancreatic carcinoma, including enlargement of pancreatic head and density changes. However, there are fewer signs of invaded large vessel and metastasis of the liver and spleen. There are fewer chances to find pancreatic duct dilation in PPL when compared with pancreatic cancer. Merkle et al[9] reported the combination of a bulky localized tumor in the pancreas without significant dilation of the main pancreatic duct strengthens a diagnosis of pancreatic lymphoma over adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, if enlarged lymph nodes are encountered below the level of the renal veins, virtual exclusion of adenocarcinoma is possible. While Arcari et al[17] insisted that imaging techniques could suggest the suspicion of PPL but are unable to distinguish PPL from pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Therefore, the final diagnosis of PPL should depend on histopathologic examination. In four of six PPL patients in current study the tissue was obtained during operation and in the other two cases the tissue was obtained by EUS- FNA. Most reported Chinese PPL cases were finally diagnosed by surgeons while there will be more studies using FNA in the future. However, when compared with surgery, it is difficult to obtain enough specimen by FNA to perform immuno-histochemical analysis and may lead to false-negative result[7]. Di Stasi et al[21] reported that CT or US guided FNA is a safe and rapid technique to make histological diagnosis by which we could get more tissues than by EUS. However during CT scan it is difficult for operators to supervise the needle path. EUS-guided tissue sampling of pancreatic masses is the superior method because it is dynamic and real-time. EUS can clearly reveal the boundary of tumor and color doppler flow imaging(CDFI) can show the vein path, sequentially guide the needle aspiration and avoid the vessel damage[22,23]. O’ Toole et al[24] reported the complication rate of EUS-FNA was as low as 1.6%, indicating it is a safe method. Most importantly, FNA depending methods should be further applied because it is helpful to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Totally four in six of our patients underwent operation. Among them two cases were treated with Whipple surgery, one by distal pancreatectomy and another by operative biliary decompression. The reason for operation is that the definitive diagnosis was not made before surgery. If these patients had been detected using FNA, the exploration could have been skipped. Thus the treatment strategy could have been direct chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Unfortunately, all published 16 Chinese PPL cases were treated with surgery, which made the final diagnosis. It can be predicted that the more frequent usage of FNA, including either CT or EUS guided-FNA may minimize the number of operations for PPL. Bouvet et al[8] reported ten in eleven PPL patients, have been performed explorative surgery, only in three of them the tumor could be fully resected. Among eight unresected cases, seven cases were treated with combined CHOP chemotherapy and radiotherapy with dosage of 30 to 45 Gy. The median survival time was 67 mo (11-191 mo). Behrns et al[1] reported that the median survival time for single chemotherapy and radiotherapy-treated PPL patients was 13 and 22 mo, respectively. While the survival time could be improved to 26 mo if combining medication with radiotherapy. Therefore, the first choice for PPL treatment should be combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, rather than surgery. With the advancement of techniques, surgery seems to be only effective when FNA is not available or diagnosis can not be made on histology. It has already been proved that single pancreas resection could not improve the survival rate of PPL but cause more complications. However, the PPL patient with biliary tract or gastrointestinal obstruction should be performed biliary or gastric bypass to relieve the symptoms.

In conclusion, PPL is a rare disease with non-specific symptoms, laboratory tests and imaging examination results. Cytology or tissue histology is fundamental for diagnosis and chemo- or radiotherapy is preferred for treatment. FNA technique is recommended as a routine examination, while total pancreatectomy is considered to have no impact on survival and with its associated morbidities, is not generally recommended for diagnosis and treatment of PPL. As a result, PPL will not be such a disease with poor prognosis in the future.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Behrns KE, Sarr MG, Strickler JG. Pancreatic lymphoma: is it a surgical disease. Pancreas. 1994;9:662–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252–260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<252::aid-cncr2820290138>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed K, Vose PC, Jarstfer BS. Pancreatic cancer: 30 year review (1947 to 1977) Am J Surg. 1979;138:929–933. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volmar KE, Routbort MJ, Jones CK, Xie HB. Primary pancreatic lymphoma evaluated by fine-needle aspiration: findings in 14 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:898–903. doi: 10.1309/UAD9-PYFU-A82X-9R9U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer. 1982;49:2112–2135. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820515)49:10<2112::aid-cncr2820491024>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nayer H, Weir EG, Sheth S, Ali SZ. Primary pancreatic lymphomas: a cytopathologic analysis of a rare malignancy. Cancer. 2004;102:315–321. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Islam S, Callery MP. Primary pancreatic lymphoma--a diagnosis to remember. Surgery. 2001;129:380–383. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvet M, Staerkel GA, Spitz FR, Curley SA, Charnsangavej C, Hagemeister FB, Janjan NA, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Surgery. 1998;123:382–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkle EM, Bender GN, Brambs HJ. Imaging findings in pancreatic lymphoma: differential aspects. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:671–675. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zucca E, Roggero E, Bertoni F, Cavalli F. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Part 1: Gastrointestinal, cutaneous and genitourinary lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:727–737. doi: 10.1023/a:1008282818705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boni L, Benevento A, Dionigi G, Cabrini L, Dionigi R. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1107–1108. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-4247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saif MW. Primary pancreatic lymphomas. JOP. 2006;7:262–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu KL, Wang RB, Xu M, Guo YH, Gong HY, LI JL, Sun HY. One case report of primary pancreatic lymphoma and literature review. Zhonghua Xiandai Neikexue Zazhi. 2006;3:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu ZL, Li ZS, Zhou GZ, Zou XP, He J, Cai QC, Hu XG, Wang Q. Analysis of clinical symptoms of pancreatic cancer: a report 1027 cases. Jiefangjun Yixue Zazhi. 2002;27:286–288. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishimura R, Takakuwa T, Hoshida Y, Tsujimoto M, Aozasa K. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: clinicopathological analysis of 19 cases from Japan and review of the literature. Oncology. 2001;60:322–329. doi: 10.1159/000058528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James JA, Milligan DW, Morgan GJ, Crocker J. Familial pancreatic lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:80–82. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arcari A, Anselmi E, Bernuzzi P, Bertè R, Lazzaro A, Moroni CF, Trabacchi E, Vallisa D, Vercelli A, Cavanna L. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Report of five cases. Haematologica. 2005;90:ECR09. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuchek JM, De Jong SA, Pickleman J. Diagnosis, surgical intervention, and prognosis of primary pancreatic lymphoma. Am Surg. 1993;59:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNulty NJ, Francis IR, Platt JF, Cohan RH, Korobkin M, Gebremariam A. Multi--detector row helical CT of the pancreas: effect of contrast-enhanced multiphasic imaging on enhancement of the pancreas, peripancreatic vasculature, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Radiology. 2001;220:97–102. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jl1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelekis NL, Semelka RC. MRI of pancreatic tumors. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:875–886. doi: 10.1007/s003300050221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Stasi M, Lencioni R, Solmi L, Magnolfi F, Caturelli E, De Sio I, Salmi A, Buscarini L. Ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy of pancreatic masses: results of a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1329–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.443_m.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallery JS, Centeno BA, Hahn PF, Chang Y, Warshaw AL, Brugge WR. Pancreatic tissue sampling guided by EUS, CT/US, and surgery: a comparison of sensitivity and specificity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:218–224. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribeiro A, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Wiersema LM, Wang KK, Clain JE, Wiersema MJ. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration combined with flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry in the diagnosis of lymphoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:485–491. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Toole D, Palazzo L, Arotçarena R, Dancour A, Aubert A, Hammel P, Amaris J, Ruszniewski P. Assessment of complications of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:470–474. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.112839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]