Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the effect of combination treatment with the interferon (IFN) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) on several fibrotic indices in patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C (CHC).

METHODS: Perindopril (an ACE-I; 4 mg/d) and/or natural IFN (3 MU/L; 3 times a week) were administered for 12 mo to refractory CHC patients, and several indices of serum fibrosis markers were analyzed.

RESULTS: ACE-Idecreased the serum fibrosis markers, whereas single treatment with IFN did not exert these inhibitory effects. However, IFN significantly augmented the effects of ACE-I, and the combination treatment exerted the most potent inhibitory effects. The serum levels of alanine transaminase and HCV-RNA were not significantly different between the groups, whereas the plasma level of transforming growth factor-β was significantly attenuated almost in parallel with suppression of the serum fibrosis markers.

CONCLUSION: The combination therapy of an ACE-Iand IFN may have a diverse effect on disease progression in patients with CHC refractory to IFN therapy through its anti-fibrotic effect.

Keywords: Interferon, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, Liver fibrosis, Chronic hepatitis C, Transforming growth factor-β

INTRODUCTION

The goal of therapy for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is the eradication of the hepatitis C virus (HCV)[1]. In the recent decade, anti-viral therapy against HCV has been markedly improved, especially treatment with ribavirin and peg-interferon (IFN)[2]. However, the overall sustained viral response (SVR), defined as undetectable HCV-RNA 6 mo after the end of treatment, even with the combination of peg-IFN and ribavirin is still unsatisfactory, since many patients have not achieved SVR yet. It is well known that continuous inflammation associated with HCV infection slowly results in liver fibrosis development, and eventually leads to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Accordingly, one of the clinical goals in the treatment of refractory CHC is to prevent the progression of liver fibrosis development[3]. It has been reported that the prognosis and clinical management of chronic liver diseases depend on the extent of liver fibrosis, as complications mainly develop in the advanced stages, which is also applicable to HCV infection[1]. Also, it has been shown that the degree of fibrosis development correlates with the incidence of HCC[4]. Collectively, it is likely that the effective anti-fibrotic therapy will significantly improve the prognosis of patients, especially in non-SVR refractory CHC.

Recent studies have shown that long-term IFN could exert beneficial effects in patients with refractory CHC[5]. Apart from the anti-viral effect, several evidences suggested that IFN could improve liver fibrosis. However, the histological improvement of liver fibrosis could be observed only in the SVR patients[6]. It has been reported that IFN inhibited the collagen promoter activity in the activated hepatic stellate cells (HSC), which play a pivotal role in liver fibrosis development[7]. Furthermore, it is well known that the combination treatment with different anti-fibrotic agents may provide synergistic rather than additive effects. Alternative strategies with other safe agents in the non-SVR patients should be used.

Recent studies have revealed that the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays an important role in the liver fibrosis development[8]. Angiotensin-II (AT-II) induces the proliferation of the activated HSC, and the local RAS components were significantly up-regulated during the liver fibrosis development[9]. It has been reported that inhibition of RAS by the clinically used angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) and AT-II type-1 receptor blocker (ARB) significantly attenuated liver fibrosis development in several experimental models[10,11]. In the clinical practice, these RAS-inhibitory agents also exerted anti-fibrotic effects in several types of chronic liver diseases, including CHC[12,13]. We previously reported that the combination treatment with IFN and ACE-Iexerted a more potent inhibitory effect on murine liver fibrosis development than either single agent[14]. In a preliminary study, we also demonstrated that the combination treatment with IFN and ACE-Isuppressed the serum fibrosis markers in CHC[15].

In the current study, we investigated whether this combination treatment would exert a more potent anti-fibrotic effect than either single agent in patients of refractory CHC. To elucidate the possible mechanisms, we also examined the serum transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) level, which is known as a key cytokine in the liver fibrogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and methods

In the current study, we examined a total 40 patients with CHC refractory with mild hypertension from July 2002 to December 2005 at Nara Medical University Hospital. The refractory CHC is defined as CHC that failed to respond to IFN mono-therapy. The patients were randomly divided into 4 groups of matching clinical background (e.g., age, sex), HCV status, and serum fibrosis markers. The treated groups were given either single or combination of oral ACE-I(perindopril: 4 mg/d) and an intramuscular injection of IFN (natural IFN: 3 MU/L; 3 times a week) for 12 mo, whereas the control group received neither agent. We recommended all patients to stop alcohol intake completely. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Nara Medical University, and the study was conducted in conformity with ethical and humane principles.

Evaluation of laboratory data

The serum fibrosis markers; namely, hyaluronic acid, type IV collagen 7S (7S-collagen), and amino-terminal peptide of type-III pro-collagen (P-III-P) were measured before and after the treatment in all patients by latex agglutination, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), and radioimmunoassay (RIA) respectively, with routine laboratory methods. The serum level was measured by ELISA kit (R&D systems, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as described previously[14]. The serum HCV status was measured by using the quantitative or qualitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis. Other serum biochemical markers, such as alanine transaminase (ALT), were measured by the routine laboratory methods.

Statistical analysis

To assess the statistical significance of the inter-group differences in the quantitative data, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test was performed after one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). This was followed by Barlett’s test to determine the homology of variance.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of the refractory CHC patients in all groups are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the patient’s clinical background among the groups. Most patients in all groups had high titer of HCV of genotype 1b, which is known for its resistance to the IFN based anti-viral therapy [2].

Table 1.

Characteristics in patients of refractry chronic hepatitis C

| Control | IFN | ACE-I | IFN+ACE-I | |

| No. of patients | 10 | 7 | 7 | 11 |

| Mean age ± SD (yr) | 60 ± 7 | 60 ± 9 | 58 ± 9 | 62 ± 8 |

| Sex (M/F) | 6/4 | 3/4 | 4/3 | 5/6 |

| Serum HCV-RNA1 (M copies/L) | 632 ± 120 | 641 ± 131 | 620 ± 106 | 628 ± 108 |

| Genotype (1 b/others) | 9/1 | 6/1 | 7/0 | 10/1 |

Data represent mean ± SD.

Serum fibrosis markers

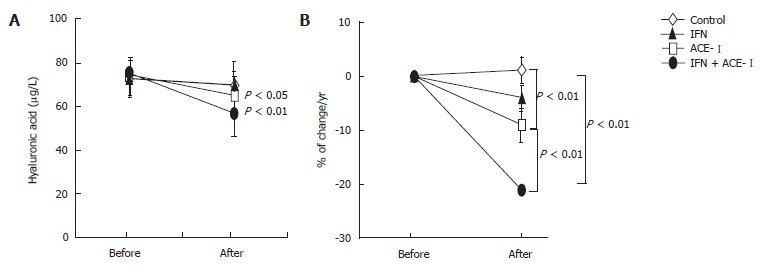

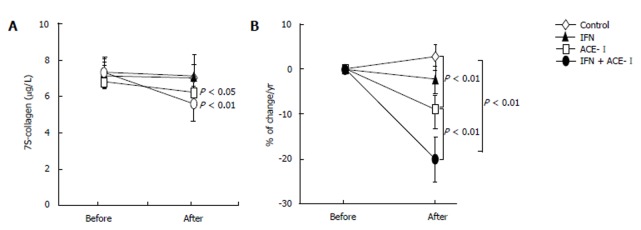

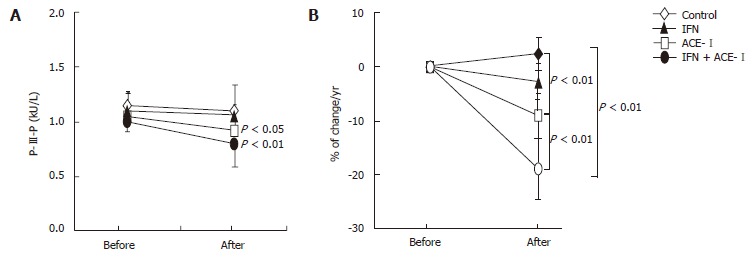

All medications were well tolerated by all patients. To examine the therapeutic effects of IFN and/or ACE-Ion the progression of liver fibrosis in patients with refractory CHC, we compared several serum fibrosis markers before and after the respective treatment. As shown in Figure 1A, there were differences in the serum hyaluronic acid among the groups. Without treatment, the mean serum hyaluronic acid level was increased (1.2% ± 1.1%) at the end of the study as compared with the starting level. Both IFN- and ACE-Itreated-groups had decreased mean serum hyaluronic acid level at the end of study (-4% ± 2.2% and -9% ± 3.4%, respectively). However, only ACE-Iexerted a significant difference as compared with the untreated control group (P < 0.01). The combination treatment of ACE-Iand IFN (IFN + ACE-I) exerted the most potent suppressive effect (-21% ± 5.9%) among all groups, and the inhibitory effect of this combination was more potent than that in the ACE-I-treated group (P < 0.01) (Figure 1B). Similar results were observed in the 7-S-collagen and P-III-P levels (Figures 2 and 3, respectively).

Figure 1.

The effects of IFN and ACE-I on the serum hyaluronic acid in the patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C. A: Hyaluronic acid level before and after the study; B: % of change in the hyaluronic acid level in each group. Control: untreated control group; ACE-I, IFN: ACE-I- and IFN-treated groups, respectively; IFN + ACE-I: combination treated group with ACE-I and IFN. The data represent the mean ± SD.

Figure 2.

The effect of IFN and ACE-I on the serum 7-S-collagen in the patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C. A: The 7-S-collagen level before and after the study; B: % of change in the 7-S-collagen level in each group. Control: untreated control group. ACE-I, IFN: ACE-I- and IFN-treated groups, respectively. IFN + ACE-I: combination treated group with ACE-I and IFN. The data represent the means ± SD.

Figure 3.

The effects of IFN and ACE-I on the serum P-III-P in the patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C. A: P-III-P level before and after the study; B: % of change in the P-III-P level in each group. Control: untreated control group. ACE-I, IFN: ACE-I- and IFN-treated group, respectively. IFN + ACE-I: combination treated group with ACE-I and IFN. The data represent the means ± SD.

Biochemical markers and serum TGF-β level

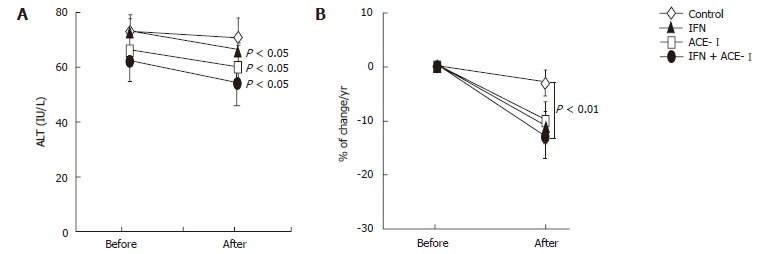

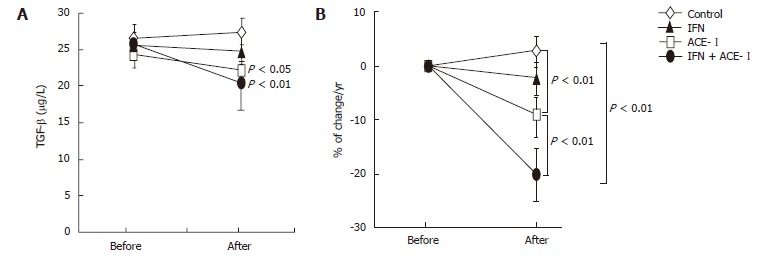

We next examined the changes in several biochemical markers. The ACE-I- and IFN + ACE-I-treated groups showed improvement in the serum ALT level at the end of the study (Figure 4A). However, in contrast to the serum fibrotic markers, there were no marked differences between both groups (Figure 4B). These results indicated that the improvement of fibrosis markers induced by ACE-Iand/or IFN were not due to the non-specific cytoprotective effects. Also, the viral status of HCV and serum creatinine (Cre) did not significantly change before and after the study in all groups. The mean blood pressure decreased in the ACE-I- and IFN + ACE-I-treated groups, although, similar to ALT, there was no difference between both groups (Table 2). Since TGF-β is known as a key cytokine in the liver fibrosis development, we next measured the TGF-β level in all experimental groups. The alterations of the TGF-β level were almost parallel to those of the fibrosis markers. The IFN + ACE-Itreatment significantly attenuated the TGF-β level at the end of the study (-20% ± 5.6%) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The effects of IFN and ACE-I on the serum ALT in the patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C. A: ALT level before and after the study; B: % of change in the ALT level in each group. Control: untreated control group. ACE-I, IFN: ACE-I- and IFN-treated groups, respectively. IFN + ACE-I: combination treated group with ACE-I and IFN. The data represent the means ± SD.

Table 2.

Changes of seveal markrs in patients of refractry chronic hepatitis C (mean ± SD)

|

Control |

IFN |

ACE-I |

IFN+ACE-I |

|||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Mean BP (mmHg) | 132 ± 14 | 130 ± 12 | 130 ± 14 | 128 ± 13 | 141 ± 16 | 128 ± 12a | 142 ± 15 | 130 ± 12a |

| HCV-RNA (M copies/L) | 632 ± 120 | 604 ± 117 | 641 ± 131 | 598 ± 95 | 620 ± 106 | 613 ± 110 | 628 ± 108 | 586 ± 90 |

| S-Cre (mg/L) | 9 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 9 ± 2 | 9 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 |

P < 0.05 vs before treatment.

Figure 5.

The effects of IFN and ACE-I on the serum TGF-β in the patients with refractory chronic hepatitis C. A: TGF-β level before and after the study; B: % of change in the TGF-β level in each group. Control: untreated control group. ACE-I, IFN: ACE-I- and IFN-treated groups, respectively. IFN + ACE-I: combination treated group with ACE-I and IFN. The data represent the means ± SD.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we showed that the combination treatment with ACE-Iand IFN significantly suppressed several serum fibrosis markers along with inhibition of TGF-β in patients with refractory CHC.

After evolvement of the combination therapy with peg-IFN and ribavirin, a significantly higher SVR rate has been achieved as compared with the IFN mono-therapy[2]. Even in the genotype 1b patients, almost half of the patients could reach the SVR status. However, from the opposite aspect, about half of the patients are still resistant to the IFN-based anti-viral therapy. Also, it is well known that this combination regimen frequently exerts several adverse effects as compared with the IFN mono-therapy, such as hemolytic anemia and potential teratogenecity. Accordingly, an alternative strategy should be developed for patients with both refractory CHC and intolerance to the combination therapy of peg-IFN and ribavirin. One of the clinical goals to be achieved for these patients is prevention of progression to liver cirrhosis and HCC[5]. It has been reported that the improvement of fibrosis stage led to suppression of hepatocarcinogenesis [4]. Taken together, it is likely that the effective anti-fibrotic therapy will significantly improve the prognosis of the patients with refractory CHC.

In addition to the anti-viral effect, several evidences suggested that IFN is also effective in curtaining liver fibrosis both in the experimental animal models and in the clinical practice[6,14]. It has been reported that IFN significantly suppressed the HSC, and it also inhibited the promoter activity of pro-collagen gene[7]. However, in the clinical practice, fibrosis improvement with IFN-based therapy could be observed only in the virological responders[6]. Since it has been reported that the combination treatment with different anti-fibrotic agents exerted a more potent inhibitory effect than single agent therapy, alternative strategies such as combination therapy with other safe agents are required.

It is well known that TGF-β is a central key cytokine in the liver fibrosis development[16]. We previously reported that the clinically used ACE-Ieven at a clinically comparable low dose significantly attenuated the experimental liver fibrosis development along with suppression of TGF-β[10,17]. In the clinical practice, a retrospective study on liver transplanted patients with CHC, re-infection with HCV revealed that the patients receiving RAS inhibitors, such as ACE-I, had significantly less fibrosis progression than those receiving other types of drugs[12]. In the current study, we found that the combination treatment with ACE-Iand IFN significantly suppressed the several serum fibrosis markers along with TGF-β inhibition as compared with ACE-Ialone. We have shown similar results in a previous experimental study[14]. The combination treatment with ACE-Iand IFN attenuated the liver fibrosis development along with suppression of the activated HSC, pro-collagen mRNA, and TGF-β. It is well known that the activated HSC play a pivotal role in the liver fibrogenesis, and that the activated HSC are one of the main cells producing TGF-β and collagen[16]. The exact mechanism of the inhibitory effect in the current study is still obscure at this time. However, we observed that the serum TGF-β, P-III-P, and 7-S-collagen were suppressed almost in parallel by this combination regimen, whereas ALT and HCV status were not altered. These results indicated that, as in the experimental study, the anti-fibrotic effect of this combination regimen was, at least partly, mediated through inhibition of the activated HSC.

It is now widely recognized that angiogenesis plays an important role in many biological phenomena, including fibrosis development[18]. It has been shown that neovascularization significantly increased during the development of liver fibrosis[19]. We previously reported that ACE-Iand IFN exerted an anti-angiogenic activit[20]. It would be possible that the anti-fibrotic effect of this combination treatment is, to some extent, mediated by suppression of neovascularization in the liver.

From the clinical point of view, liver biopsy is still considered the “gold standard” to assess the fibrosis development[16]. However, liver biopsy is associated with potential morbidity and mortality and has several limitations, including sampling error and inter-observer variability[21]. Recent studies have shown that evaluation of the serum fibrosis markers can predict the degree of fibrosis to an extent similar to that of liver biopsy[22]. Although we did not perform liver biopsy in the current study, further studies are required in the future to examine the histological and immunohistochemical markers, such as smooth muscle α-actin which is known as a marker of the activated HSC, and to make comparison with the serum fibrosis markers. Furthermore, in the next step, we have to examine whether this IFN+ACE-Iregimen is also effective for the CHC patients refractory to the combination therapy of peg-IFN and ribavirin.

In summary, we found in our present study that the combination treatment with ACE-Iand IFN significantly attenuated the serum fibrosis markers along with suppression of TGF-β in patients with refractory CHC. This combination treatment may become a new strategy to prevent disease progression in the patients with refractory CHC through its anti-fibrotic effect.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Bai SH

References

- 1.Poynard T, Yuen MF, Ratziu V, Lai CL. Viral hepatitis C. Lancet. 2003;362:2095–2100. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi N, Takehara T. Antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C: past, present, and future. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sethi A, Shiffman ML. Approach to the management of patients with chronic hepatitis C who failed to achieve sustained virologic response. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006;20:115–135. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Befeler AS, Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1609–1619. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito Y, Saito H, Tada S, Nakamoto N, Horikawa H, Kurita S, Kitamura K, Ebinuma H, Ishii H, Hibi T. Effect of long-term interferon therapy for refractory chronic hepatitis c: preventive effect on hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:1491–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiratori Y, Imazeki F, Moriyama M, Yano M, Arakawa Y, Yokosuka O, Kuroki T, Nishiguchi S, Sata M, Yamada G, et al. Histologic improvement of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C who have sustained response to interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:517–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inagaki Y, Nemoto T, Kushida M, Sheng Y, Higashi K, Ikeda K, Kawada N, Shirasaki F, Takehara K, Sugiyama K, et al. Interferon alfa down-regulates collagen gene transcription and suppresses experimental hepatic fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2003;38:890–899. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Fukui H. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitors may be an alternative anti-angiogenic strategy in the treatment of liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Possible role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:348–356. doi: 10.1159/000069792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bataller R, Sancho-Bru P, Ginès P, Brenner DA. Liver fibrogenesis: a new role for the renin-angiotensin system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1346–1355. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Nakatani T, Tsujinoue H, Fukui H. Angiotensin-II type 1 receptor interaction is a major regulator for liver fibrosis development in rats. Hepatology. 2001;34:745–750. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshiji H, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Tsujinoue H, Nakatani T, Imazu H, Yanase K, Kuriyama S, Fukui H. Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system attenuates liver enzyme-altered preneoplastic lesions and fibrosis development in rats. J Hepatol. 2002;37:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rimola A, Londoño MC, Guevara G, Bruguera M, Navasa M, Forns X, García-Retortillo M, García-Valdecasas JC, Rodes J. Beneficial effect of angiotensin-blocking agents on graft fibrosis in hepatitis C recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:686–691. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000128913.09774.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terui Y, Saito T, Watanabe H, Togashi H, Kawata S, Kamada Y, Sakuta S. Effect of angiotensin receptor antagonist on liver fibrosis in early stages of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:1022. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Noguchi R, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Kitade M, Yamazaki M, Tsujinoue H, et al. Combination of interferon-beta and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, perindopril, attenuates the murine liver fibrosis development. Liver Int. 2005;25:153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshiji H, Noguchi R, Fukui H. Combined effect of an ACE inhibitor, perindopril, and interferon on liver fibrosis markers in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:215–216. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis -- from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshiji H, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Yanase K, Tsujinoue H, Imazu H, Fukui H. Suppression of the renin-angiotensin system attenuates vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated tumor development and angiogenesis in murine hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:1227–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Hicklin DJ, Wu Y, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Yamazaki M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and receptor interaction is a prerequisite for murine hepatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 2003;52:1347–1354. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noguchi R, Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Kitade M, Yamazaki M, Mitoro A, et al. Combination of interferon-beta and the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, perindopril, attenuates murine hepatocellular carcinoma development and angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6038–6045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regev A, Berho M, Jeffers LJ, Milikowski C, Molina EG, Pyrsopoulos NT, Feng ZZ, Reddy KR, Schiff ER. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2614–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontana RJ, Lok AS. Noninvasive monitoring of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S57–S64. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]