Abstract

AIM: To investigate the factors contributing to health-related quality of life (HRQL) in chronic liver disease (CLD).

METHODS: Patients with CLD and age- and sex-matched normal subjects performed the validated Thai versions of the short-form 36 (SF-36) by health survey and chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ). Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to assess the impact of disease severity, demography, causes of CLD, socioeconomic factors, and self-rating health perception on HRQL.

RESULTS: Two-hundred and fifty patients with CLD and fifty normal subjects were enrolled into the study. Mean age and the numbers of low educated, unemployed, blue-collar career and poor health perception increased significantly from chronic hepatitis to Child’s Classes A to B to C. Advanced stage of CLD was related to deterioration of HRQL. Increasing age and female reduced physical health area. Low socioeconomic factors and financial burden affected multiple areas of HRQL. In overall, the positive impact of self-rating health perception on HRQL was consistently showed.

CONCLUSION: Advanced stages of chronic liver disease, old age, female sex, low socioeconomic status and financial burden are important factors reducing HRQL. Good health perception improves HRQL regardless of stages of liver disease.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, Cirrhosis, Chronic hepatitis, Short-form 36, Chronic liver disease questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

In 1947, the World Health Organization expanded the definition of health to include in addition to the absence of disease, a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being[1]. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) emerges as a tool for measuring outcome from the patient’s viewpoint, incorporating social, psychological, physiological and physical functioning[1,2]. Combined using generic and disease-specific instruments can provide more accurate assessment of both the global aspects and the specific features of HRQL of a specific condition[1]. The assessment of HRQL has been done in gastrointestinal diseases and chronic liver disease (CLD)[3-7]. It has been reported that the presence of CLD reduce HRQL and the deterioration of HRQL is apparent while the severity of disease increases[8-13]. Furthermore, demographic factors such as age and gender, alcohol, co-morbid illness, disease awareness and psychological status can affect HRQL in CLD[8-15]. However, a recent study showed that active psychiatric illness and medical co-morbidities, but not severity of liver disease, were determinants of HRQL reduction[16]. Previous researches of HRQL in normal and chronic medical conditions showed that socioeconomic and demographic factors can influence HRQL[17-20]. The contribution of socioeconomic factors and health perception to HRQL was not known in CLD. Self-rating patient health perception is one of the strongest predictors of mortality[21]. HRQL in CLD may be improved by changing patient health perception if there is a relationship between health perception and HRQL. The impact of marital status on HRQL is our interest because its significance had never been studied in CLD[8-13]. Our assumption was that married couple would have more psychosocial and emotional support than single, unmarried or divorced people. An earlier study revealed that HRQL in Thai patients with CLD was lower than that of normal subjects similar to the reports from Western countries[22]. We aimed to investigate variables that truly affected HRQL, such as disease severity, etiology of liver disease, demographic and socioeconomic factors, and patient health perception in Thai patients with CLD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

A cross-sectional study was carried out at the Gastroen-terological Clinic between 1st January 2004 and 30th June 2004. Eligible patients with CLD, age 15-80 years, both men and women, were enrolled consecutively into the study. Exclusion criteria were the concomitant presence of hepatic encephalopathy, active medical co-morbidity, malignancy, current or previous treatment of antiviral agents and those who refused to participate with the study. CLD were classified into chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. Chronic hepatitis was defined by the elevation of serum transaminase higher than 1.5 times of upper normal limit for 6 mo. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed from clinical finding, biochemical test, ultrasound or liver histology[23]. The staging of cirrhosis was graded according to Child-Pugh classification: Child’s classes A, B and C[24]. Causes of CLD were divided into viral hepatitis, alcohol, viral hepatitis combining with alcohol, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and miscellaneous causes. Alcohol was the etiology of CLD if daily alcohol drinking was greater than 40 g for at least 10 years. The cause of CLD was viral hepatitis B if hepatitis B surface antigen (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) was positive, or viral hepatitis C if antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) was positive. Data were collected from patient inquiry and medical records. Normal subjects who did not have medical illness were invited into the study. The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethical Committee and it was carried out according to the Helsinki Declaration Guidelines[25]. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the study.

Data collection

HRQL instruments (dependent variables): The study patients were asked to self-administer the short-form 36 (SF-36) heath survey and chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ), and the answered questionnaires were checked for completeness by a research assistant who also helped interviewing illiterate patients for the questionnaires. The SF-36 consists of 36 items which are categorized into 8 domains of physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores reflecting better perception of health. Physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain and general health represent physical health scale, whereas vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health define mental health scale. The domain scores were calculated according to the standard reference[26].

There are 29 items in the CLDQ summarized into 6 domains of abdominal symptoms, fatigue, systemic symptoms, activity, emotional function and worry. Each item consists of 7 linkert scales. Domain score is calculated from the average score of all items of that domain[7]. Both questionnaires were formally translated from the original versions and the validation of the questionnaires was reported elsewhere[22,27].

Definition of study variables (independent varia-bles): Clinical, demographic and socioeconomic data were collected from each subject. Marital status was dichotomized into single and paired. Single was extended to include unmarried person, divorced or deceased couple. Socioeconomic status was assessed by using the level of education: lower than bachelor’s degree and equal to or higher than bachelor’s degree; presence and types of career: unemployed, blue-collar and white-collar; presence or absence of financial burden. Subjects were asked to rate their health as “very good”, “good”, “fair”, “poor” or “very poor”. Good health perception included “very good”, “good” and “fair”. Poor health perception consisted of “poor” and “very poor”.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation) and analyzed using SPSS (version 11.5; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) Categorical data are described as number and percentage [n (%)]. Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD and median (range). Statistical analysis of continuous data was performed with One-way Anova or non-parametric methods as appropriate. χ2 test was used for analysis of discrete data, which give us the preliminary understanding of the association of the HRQL and studied variables. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to study the influence of independent variables on the CLDQ and SF-36 domains while controlling the effect of other variables. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 364 patients with CLD attended the Gastroenterology Clinic during the 6-mo period. Of these, 114 patients were ineligible for the study: 80 patients were either currently receiving or had received antiviral therapy; 17 patients had hepatocellular carcinoma; 13 patients had active co-morbid illness; two patients were having hepatic encephalopathy and two patients refused to participate in the study. Two-hundred and fifty subjects with CLD, and 50 normal subjects were enrolled into the study. Mean age (range) of the whole group was 48.1 (18-77) years. The number (%) of male to female ratio was 188:112 (62.7%:37.3%). The details of clinical, demographic and socioeconomic data are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients in both groups was male and had education lower than bachelor’s degree. Although both groups reported financial problems in equal proportion, the socioeconomic status of CLD group was inferior to that of normal group, which was shown from the higher number of unemployed subjects and blue-collar typed career in the former group (P < 0.01). It is not surprising that poor health perception was more frequent in the CLD than the normal group. In this study, there were only 16 (6.4%) patients with Child’s class C cirrhosis, and viral hepatitis was the most common cause of CLD (58.8%), followed by chronic alcoholic (17.2%) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (10.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline data of chronic liver disease and normal groups

| Variable | Chronic liver disease | Normal group | P |

| n | 250 | 50 | |

| Age (Mean ± SD, yr) | 49.1 ± 8.5 | 47.9 ± 12.0 | 0.65 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 160 (64.0%) | 28 (56.0%) | 0.33 |

| Marital status1 | |||

| Single | 71/238 (29.8%) | 9/49 (18.4%) | 0.07 |

| Educational level1 | |||

| < Bachelor degree | 165/237 (69.6%) | 30/50 (60.0%) | 0.12 |

| Career1 | |||

| Unemployed | 61/231 (26.4%) | 3/46 (6.5%) | < 0.01 |

| Blue-collar | 37/231 (16.0%) | 1/46 (2.2%) | |

| White-collar | 133/231 (57.6%) | 42/46 (91.3%) | |

| Financial burden1 | |||

| Present | 87/238 (36.6%) | 22/50 (44.0%) | 0.20 |

| Self-rating health perception1 | |||

| Poor health perception | 61/238 (25.6%) | 4/50 (8.0%) | < 0.01 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Chronic hepatitis | 135/250 (54.0%) | ||

| Child’s class A cirrhosis | 59/250 (23.6%) | ||

| Child’s class B cirrhosis | 40/250 (16.0%) | ||

| Child’s class C cirrhosis | 16/250 (6.4%) | ||

| Causes of chronic liver disease | |||

| Viral hepatitis B | 99 (39.6%) | ||

| Viral hepatitis C | 48 (19.2%) | ||

| Alcohol | 43 (17.2%) | ||

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 27 (10.8%) | ||

| Others | 33 (13.2%) |

Incomplete data.

Association of variables and disease severity

Similar to previous reports of any chronic liver diseases, male predominated in this study. The greatest number of single was found in chronic hepatitis group (P < 0.01). Mean age of this group was the lowest and age increased in advanced stages of CLD (P < 0.01). Low socioeconomic status, which was represented by lower education, unemployment and blue-collar typed career, increased in advanced stages of CLD. The reason of this finding is not known. Low socioeconomic status may keep the patients from appropriate treatment; hence the deterioration of liver disease is likely to happen. The proportion of good health perception decreased while the severity of CLD went up (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variables by severity of the liver diseases

| Variable | Normal | Chronic hepatitis | Child’s class A | Child’s class B | Child’s class C | P |

| n | 50 | 135 | 59 | 40 | 16 | |

| Age (Mean ± SD, yr) | 49.1 ± 8.5 | 43.5 ±12.2 | 51.7 ± 9.1 | 54.1 ± 10.2 | 54.6 + 8.0 | < 0.01 |

| Male | 28 (56%) | 88 (65.2%) | 39 (66.1%) | 22 (55%) | 10 (62.5%) | 0.73 |

| Single1 | 9/49 (18.4%) | 55/133 (41.4%) | 7/53 (13.2%) | 7/37 (18.9%) | 3/15 (20.0%) | < 0.01 |

| Low education1 | 30/50 (60%) | 79/133 (59.4%) | 39/53 (73.6%) | 33/36 (91.7%) | 14/15 (93.3%) | < 0.01 |

| Unemployment1 | 2/50 (4.0%) | 16/133 (12.0%) | 11/53 (20.8%) | 14/37 (37.8%) | 3/15 (20.0%) | < 0.01 |

| Blue-collar career1 | 1/46 (2.2%) | 16/129 (12.4%) | 8/51 (15.7%) | 6/37 (16.2%) | 7/15 (46.7%) | < 0.01 |

| Financial burden1 | 22/50 (44.0%) | 46/133 (34.6%) | 22/53 (41.5%) | 14/37 (37.8%) | 5/15 (33.3%) | 0.77 |

| Good health perception1 | 46/50 (92.0%) | 106/133 (79.7%) | 38/53 (71.7%) | 24/37 (64.9%) | 9/15 (60.0%) | < 0.01 |

Incomplete data.

The effect of disease severity on HRQL by univariate analysis

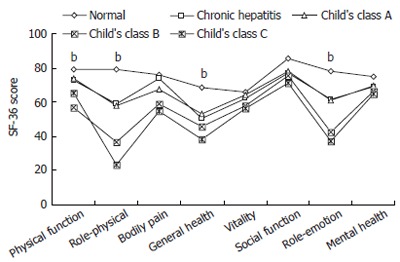

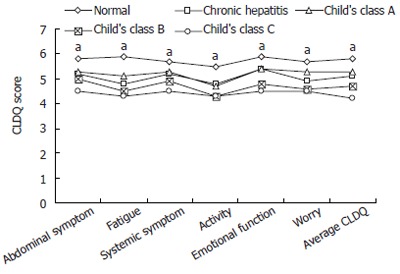

By univariate analysis, higher stages of CLD decreased HRQL in some domains of the SF-36, such as physical function, role-physical, general health and role-emotion (P < 0.001), and in all area of the CLDQ (P < 0.03). However, we could not make a conclusion that advanced stages of CLD reduced the HRQL due to the presence of several confounding factors in advanced stages of CLD, such as old age, low socioeconomic status and poor health perception (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

The domain scores of short-form 36 (SF-36) by disease severity. bP < 0.001 vs normal group.

Figure 2.

The domain scores of chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) by disease severity. aP < 0.03 vs normal group.

Influence of disease stage and variables on HRQL while controlling other variables

Multiple regression analysis of the association of HRQL domains and multiple variables such as stages of CLD, self-rating health perception, age, sex, financial burden, type of career, education level and viral hepatitis infection as a cause of CLD was performed. The advanced stages of CLD reduced all of the CLDQ domains, the majority of physical health scales of the SF-36 (physical functioning, role-physical and general health) and role-emotional domains. A one-year increase in age was associated with the reduction of 3 domains of physical heath scales of the SF-36 (physical functioning, role-physical and bodily pain), similar to the negative effect of female on physical functioning. While the presence of financial burden decreased multiple domains of the SF-36 and CLDQ, lower levels of education and career reduced predominantly the domains of mental health scales (vitality and role-emotion, respectively). Good health perception increased the SF-36 and CLDQ scores across the board. Viral hepatitis infection was not shown to affect any domains of HRQL (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Variables affecting SF-36 domains1

| Variable | Physical function | Role-physical | Bodily pain | General health | Vitality | Social function | Role-emotion | Mental health |

| Good health perception | 13.7 (2.6) | 36.4 (5.4) | 21.6 (5.3) | 26.2 (2.9) | 17.2 (2.1) | 15.8 (2.8) | 23.1 (5.9) | 18.0 (2.2) |

| Advanced stage | -3.1 (1.0) | -7.5 (2.2) | -4.0 (1.1) | -6.1 (2.4) | ||||

| Age (yr) | -0.4 (0.1) | -0.6 (0.2) | -0.8 (0.2) | |||||

| Female | -6.3 (2.2) | |||||||

| Financial burden | -6.9 (2.2) | -15.8 (4.6) | -4.4 (1.8) | -17.0 (5.0) | -6.9 (1.9) | |||

| Low education | -4.7 (1.8) | |||||||

| High level career | 7.7 (3.0) | |||||||

| F-statistic | 18.5 | 26.2 | 18 | 55.6 | 32.2 | 31.7 | 13.3 | 42.8 |

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

1Only data with P < 0.05 are expressed as β-coefficient (SEM).

Table 4.

Variables affecting CLDQ domains1

| Variable | Abdominal symptoms | Fatigue | Systemic symptoms | Activity | Emotional function | Worry | Average CLDQ |

| Good health perception | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| Advanced stage | -0.2 (0.1) | -0.3 (0.1) | -0.2 (0.1) | -0.2 (0.1) | -0.3 (0.1) | -0.2 (0.1) | -0.3 (0.1) |

| Financial burden | -0.4 (0.1) | -0.3 (0.1) | -0.3 (0.2) | ||||

| F-statistic | 29 | 22.2 | 24.5 | 19.2 | 36.3 | 16.1 | 25.2 |

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

1Only data with P < 0.05 are expressed as β-coefficient (SEM).

DISCUSSION

Patients with CLD usually have HRQL lower than normal population, and the deterioration of HRQL appears while the severity of CLD increases[8-13]. This study focus not only on liver disease factors but also on other variables, such as age, sex, family support, socioeconomic status (education level, employment and career type), financial burden and self-rating health perception. Multiple regression analysis was performed to confirm the effect of variables on HRQL while controlling the influence of other variables. Advanced stages of CLD reduced all domains of the CLDQ, and the physical function, role-physical, general health and role-emotion domains of the SF-36. The effect of viral hepatitis infection as causes of CLD on HRQL reported from several studies is still inconclusive[15,28]. Recent systematic review revealed that the patients with HCV infection scored lower than the controls across all domains of the SF-36[27]. In our study, we could not find the impact of viral hepatitis infection, especially viral hepatitis C, on HRQL. However, the total cases of HCV infection in the study were quite low. There were only 48 (19.2%) patients with HCV infection distributing in three stages of cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis. In general, the elderly is associated with less favorable appraisal of personal health due to their health concerns, pessimistic health appraisals, social isolation and unemployment[29]. A previous study in CLD revealed that old age had a negative impact on HRQL[11]. Nevertheless, another study reported that cirrhotic patients with younger age had a more impairment in HRQL than the elder[9]. While important factors were controlled, a one-year increase in age reduced the scores of physical function, role-physical, and bodily pain from 0.4 to 0.8. In general, females have more health concerns and are more treatment-seeker than male. One study in CLD reported the minor effect of gender on HRQL in CLD[11]. We found that female gender yielded negative influence on physical functioning. Surprisingly, the marital status did not affect HRQL. This finding may be explained by the close-knit type of Thai society, so CLD patients could get psychosocial support from other family members even when they are single or divorced. Low socioeconomic status was shown to be important factor affecting HRQL in normal population and in patients with medical illnesses, such as prostate cancer, end-stage renal diseases and lung cancer[18-20,30]. Education level and career type were used as markers of socioeconomic status in this study because there is no standard categorization of socioeconomic status in Thailand. In general, education can help people cope their own problems. Low educated people are prone to have psychological problems and have false beliefs. People with lower socioeconomic status have more stress, more depression and interfamilial relationship problems in their life. As far as we know, there is only one study in chronic hepatitis C that reported the effect of education on HRQL[15]. We found that lower education level and type of career reduced vitality and role-emotion. The presence of financial burden can lower HRQL in several areas of the SF-36 and CLDQ. The impact of low socioeconomic status on HRQL supports the proposed conceptual model of HRQL by Wilson IB and Cleary PD in 1995, which states that socioeconomic factors influence multiple domains of functional status[21]. The most important contribution showed from our study is that self-rating patient health perception can affect HRQL in CLD. In the conceptual model, health perception is included in the model together with other factors, such as biological and physiological variables, symptom status, functional status, characteristics of individual and environment[21]. We found that the proportion of good health perception declined while the severity of CLD increased. Good health perception was the only factor shown to be positively associated with the SF-36 and CLDQ domains unanimously. This finding supports the HRQL model that health perception is related to functional status, symptom status, biological and physiological variables. It is possible that HRQL in CLD can be improved by searching strategy to increase patient’s health perception. There is some evidence showing that psychological and emotional support can improve patient health perception[31].

In this study, we showed that the important factors that reduced HRQL in CLD included not only advanced stages of CLD but also old age, female sex, low socioeconomic status, financial burden, as well as poor health perception in accordance with the conceptual model of HRQL. We conclude that while medical treatment is a key to improve patient condition and HRQL, additional treatment with psychosocial support to raise patient health perception may improve HRQL, perhaps even better.

COMMENTS

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) in chronic liver disease patients is lower than normal population. Factors relating to the reduction of HRQL are inconsistently reported. The study of factors affecting HRQL in chronic liver disease in Asians has never been carried out.

Research frontiers

The data of several variables, e.g. disease severity, etiologic factor, demographic and socioeconomic, and patient self-rating health perception were collected. Then, multiple regression analysis was used to identify the factors that independently affect HRQL in chronic liver disease.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The study demonstrated that advanced stages of chronic liver disease, old age and female sex reduced HRQL in Thai patients. Furthermore, socioeconomic factors which hardly receive attention in previous studies of HRQL in chronic liver disease can affect HRQL. Importantly, this is the first time that patient health perception is shown to be strongly associated with HRQL in chronic liver disease.

Applications

While the medical treatment is a key to improve patient condition and HRQL, complementary treatment with psychosocial support aimed to raise patient health perception may improve HRQL. This conclusion needs further study to confirm.

Terminology

HRQL is a concept which reflects the physical, social, and emotional attitudes and behaviors of an individual as they relate to their prior and current health state. HRQL assessment describes health status from patients’ perspective and serves as a powerful tool to assess and explain disease outcomes.

Peer review

This study concerns over the understanding of readers for the demonstration of results from multiple regression analysis. The key point of the analysis is to show if the presence of individual relating factor affects HRQL in chronic liver disease. Overall the paper requires grammatical work.

Footnotes

Supported by Thailand Research Fund

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Martin LM, Sheridan MJ, Younossi ZM. The impact of liver disease on health-related quality of life: a review of the literature. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4:79–83. doi: 10.1007/s11894-002-0041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa KH. Description of a health-related quality of life conceptual model. Outcomes Manag Nurs Pract. 1999;3:78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. Impact of functional dyspepsia on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:584–589. doi: 10.1007/BF02064375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irvine EJ, Feagan B, Rochon J, Archambault A, Fedorak RN, Groll A, Kinnear D, Saibil F, McDonald JW. Quality of life: a valid and reliable measure of therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial Study Group. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:287–296. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90585-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Younossi ZM, Guyatt G. Quality-of-life assessments and chronic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1037–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgaonkar MR, Irvine EJ. Quality of life measurement in gastrointestinal and liver disorders. Gut. 2000;47:444–454. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, Boparai N, King D. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295–300. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younossi ZM, Boparai N, McCormick M, Price LL, Guyatt G. Assessment of utilities and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:579–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, Salerno F, Merli M, Panella C, Loguercio C, Apolone G, Niero M, Abbiati R. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:170–178. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chong CA, Gulamhussein A, Heathcote EJ, Lilly L, Sherman M, Naglie G, Krahn M. Health-state utilities and quality of life in hepatitis C patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:630–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younossi ZM, Boparai N, Price LL, Kiwi ML, McCormick M, Guyatt G. Health-related quality of life in chronic liver disease: the impact of type and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2199–2205. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arguedas MR, DeLawrence TG, McGuire BM. Influence of hepatic encephalopathy on health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1622–1626. doi: 10.1023/a:1024784327783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Córdoba J, Flavià M, Jacas C, Sauleda S, Esteban JI, Vargas V, Esteban R, Guardia J. Quality of life and cognitive function in hepatitis C at different stages of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2003;39:231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain KB, Fontana RJ, Moyer CA, Su GL, Sneed-Pee N, Lok AS. Comorbid illness is an important determinant of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2737–2744. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarzinger M, Dewedar S, Rekacewicz C, Abd Elaziz KM, Fontanet A, Carrat F, Mohamed MK. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection: does it really impact health-related quality of life A study in rural Egypt. Hepatology. 2004;40:1434–1441. doi: 10.1002/hep.20468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Häuser W, Holtmann G, Grandt D. Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(03)00315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djibuti M, Shakarishvili R. Influence of clinical, demographic, and socioeconomic variables on quality of life in patients with epilepsy: findings from Georgian study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:570–573. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thumboo J, Fong KY, Machin D, Chan SP, Soh CH, Leong KH, Feng PH, Thio St, Boey ML. Quality of life in an urban Asian population: the impact of ethnicity and socio-economic status. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penson DF, Stoddard ML, Pasta DJ, Lubeck DP, Flanders SC, Litwin MS. The association between socioeconomic status, health insurance coverage, and quality of life in men with prostate cancer. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:350–358. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sesso R, Rodrigues-Neto JF, Ferraz MB. Impact of socioeconomic status on the quality of life of ESRD patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:186–195. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobhonslidsuk A, Silpakit C, Kongsakon R, Satitpornkul P, Sripetch C. Chronic liver disease questionnaire: translation and validation in Thais. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1954–1957. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i13.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leevy CM, Sherlock S, Tygstrup N, Zetterman R. Cirrhosis. In: Disease of the liver and biliary tract., editor. Standardization of nomenclature, diagnostic criteria and prognosis. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherlock S, Dooley J. Disease of the liver and biliary system. 10th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1997. pp. 135–180. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principals for research involving human subjects. Ferney-Voltaire, French: The Association; 2004. Available from: http://www.wma.net/e/ethicsunit/helsinki.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski MK, Gadnek B. Scoring the SF-36. In: SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and interpretation Guide., editor. Boston, MA: Nimrod Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kongsakon R, Silpakit C. Thai version of the medical outcome study in 36 items short form health survey: an instrument for measuring clinical results in mental disorder patients. Rama Med J. 2000;23:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel BM, Younossi ZM, Hays RD, Revicki D, Robbins S, Kanwal F. Impact of hepatitis C on health related quality of life: a systematic review and quantitative assessment. Hepatology. 2005;41:790–800. doi: 10.1002/hep.20659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrity TF, Somes GW, Marx MB. Factors influencing self-assessment of health. Soc Sci Med. 1978;12:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montazeri A, Hole DJ, Milroy R, McEwen J, Gillis CR. Quality of life in lung cancer patients: does socioeconomic status matter. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng C, Hui WM, Lam SK. Psychosocial factors and perceived severity of functional dyspeptic symptoms: a psychosocial interactionist model. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:85–91. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106885.40753.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]