Abstract

AIM: To describe and discuss echo-enhanced sonography in the differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions.

METHODS: The pulse inversion technique (with intravenous injection of 2.4 mL SonoVue®) or the power-Doppler mode under the conditions of the 2nd harmonic imaging (with intravenous injection of 4 g Levovist®) was used for echo-enhanced sonography.

RESULTS: Cystadenomas frequently showed many vessels along fibrotic strands. On the other hand, cystadenocarcinomas were poorly and chaotically vascularized. ”Young pseudocysts” were frequently found to have a highly vascularised wall. However, the wall of the ”old pseudocysts” was poorly vascularized. Data from prospective studies demonstrated that based on these imaging criteria the sensitivities and specificities of echo-enhanced sonography in the differentiation of cystic pancreatic masses were > 90%.

CONCLUSION: Cystic pancreatic masses have a different vascularization pattern at echo-enhanced sonography. These characteristics are useful for their differential diagnosis, but histology is still the gold standard.

Keywords: Cystic pancreatic lesions, Differential diagnosis, Echo-enhanced sonography

INTRODUCTION

Cystic tumours of the pancreas are rare, accounting for about 1% of all pancreatic neoplasms[1]. Cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas are the most frequently encountered cystic lesions[1-3]. There are problems in the differentiation of cystic pancreatic masses. It is obvious that the discrimination between these lesions is critical for prognosis and therapy[4].

Conventional transabdominal ultrasound displays no characteristic signs for the differentiation of cystic pancreatic tumours and the diagnostic accuracy is low [5-7]. The vascularization pattern is helpful for the tumour differentiation and can be investigated by fundamental power and colour Doppler sonography. However, there is a low sensitivity of these procedures for detecting low blood flow velocity or small vessels. The sensitivity can be increased by echo-enhancers, such as SonoVue®. Therefore, echo-enhanced sonography is an increasingly used procedure for the differentiation of pancreatic tumours[8,9].

In this review, echo-enhanced sonography in the differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic tumours is depicted and discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients were investigated first by conventional sonography using a dynamic sector scanner. A special preparation of the patients was not necessary. The pulse inversion technique or the power-Doppler mode under the conditions of the 2nd harmonic imaging was used for echo-enhanced sonography. The pulse inversion mode was used more frequently than the 2nd harmonic imaging.

For echo-enhanced sonography, the pulse inversion 2.4 mL SonoVue® (sulfur hexafluoride gas-based contrast agent, Bracco International B.V., Amsterdam, Netherlands) was injected intravenously, and the mechanical index varied between 0.1 and 0.2 (low MI procedure). The investigation could be done in real time, and lasted for approximately 2 min.

Echo-enhanced power Doppler sonography was started immediately after intravenous injection of 4 g Levovist® (galactose-based contrast agent, concentration 300 mg/mL, Schering AG, Berlin, Germany). Intermittent sweeps were done, and the investigation lasted for approximately 2 min. One focus zone with depth adapted to the area of interest and a mechanical index of 0.8-1.3 (high MI procedure) should be used.

RESULTS

Criteria for the differentiation of pancreatic masses by conventional and echo-enhanced sonography[10,11] are shown in Table 1. Cystadenomas consisting of small cystic areas (< 3 cm) and thin fibrotic strands are shown in Figure 1A. At echo-enhanced sonography highly vascularized solid tumour parts and arteries along the fibrotic strands are shown in Figure 1B. On the other hand, cystadenocarcinomas were found to have large cystic areas (about 5 cm) and solid tumour parts in the conventional ultrasound examination (Figure 2A). After injection of an echo-enhancer, poorly vascularized solid areas could be detectable (Figure 2B). Pseudocysts were found to be characterised by an echo-free pattern and a sharply delineated wall (Figure 3A). In the remaining pancreatic parenchyma features of chronic inflammation such as calcifications and a dilated Wirsung’s duct could also be found. After injection of an echo-enhancer the wall of the pseudocysts was highly (”young cyst”, Figure 3B) or poorly vascularized (”old cysts”).

Table 1.

Criteria for differentiation of cystic pancreatic tumours with conventional ultrasound, fundamental power Doppler sonography, and echo-enhanced ultrasound[10,11]

| Conventional ultrasound | Fundamental power Doppler sonography | Echo-enhanced sonography | |

| Cystadenoma | • small cystic areas (often < 3 cm) | • no tumour vessels detectable | • highly vascularised tumour arteries along the fibrotic strands |

| • spoke-like pattern of fibrotic strands with small calcifications | |||

| • no dilated Wirsung's duct | |||

| Cystadeno- carcinoma | • large cystic areas (often > 5 cm) • solid areas | • rarely tumour vessels with chaotic pattern detectable | • poorly and chaotic vascularised solid areas |

| • no dilated Wirsung's duct | |||

| Pseudocyst | • often echo-free pattern | • rarely tumour vessels detectable in ”young cysts” | • ”young cysts” (a few weeks of age) show often a highly vascular-ised wall |

| • sharply delineated wall | |||

| • features of acute and/or chronic pancreatitis | |||

| • signs of bleeding and/or calcifica-tions • bowel infiltration is possible | • ”old cysts” (a few months of age) show often a poorly vascularised wall |

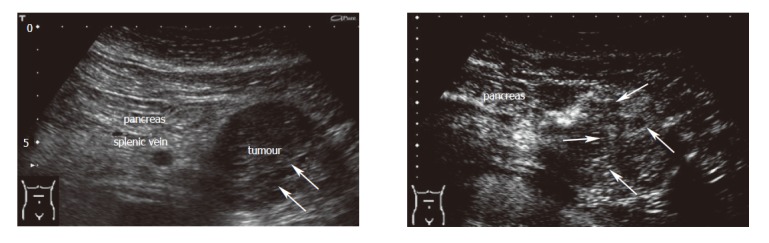

Figure 1.

Cystadenoma at conventional and echo-enhanced ultrasound. A: A tumour at the pancreatic tail (5 cm in diameter) with small cystic areas (small arrows) and thin fibrotic strands; B: Highly vascularized tumour arteries (large arrows) along the fibrotic strands (maximum of contrastation 15 s after injection of the echo-enhancer).

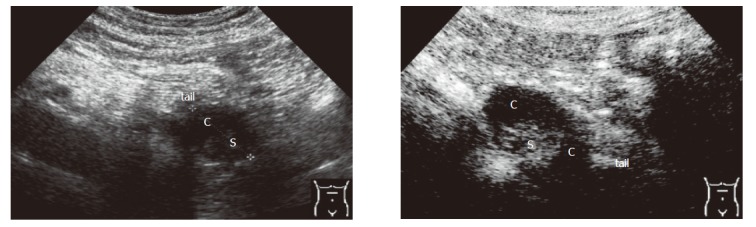

Figure 2.

Cystadenoma at conventional and echo-enhanced ultrasound A: A tumour (7 cm in diameter) at the pancreatic tail with large cystic (c) and solid areas (s); B: A poorly vascularized solid (s) tumour (maximum of contrastation 15 s after injection of the echo-enhancer).

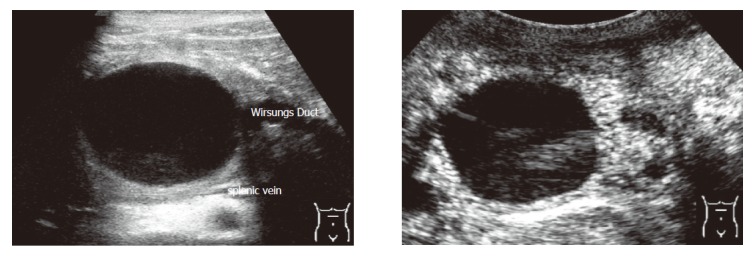

Figure 3.

Pseudocust at conventional and echo-enhanced ultrasound A: A lesion with an echo-free pattern and a sharply delineated wall. The Wirsungs Duct is dilated; B: A highly vascularized wall (maximum of contrastation 20 s after injection of the echo-enhancer).

A recently published study with 31 patients showed that echo-enhanced sonography could differentiate cystic neoplasms from pseudocysts[12]. The sensitivity of echo-enhanced sonography with respect to diagnosing cyst adenomas was 95% and its specificity was 92%. The corresponding values for pseudocysts were both 100%. However, one cystadenoma was misdiagnosed as a cyst- adenocarcinoma, and vice-versa. The morphological variability of these cystic lesions at conventional ultrasound and the difficulties in the evaluation of the vascularization of cystic masses might be responsible for the false results. On the other hand, only 27% of cyst- adenomas and 67% of pseudocysts could be correctly classified by conventional ultrasound[12].

DISCUSSION

So far not a single ideal diagnostic procedure is available for the differentiation of cystic pancreatic tumours. Histology is the gold standard but nevertheless can produce false negative results. The correct differential diagnosis of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas has proven to be difficult and imaging techniques have low correct diagnosis percentages[5,13-15], which can be attributed to the particular anatomicropathological features of these tumors and the difficulty to discriminate them from pseudocysts.

Conventional ultrasound cannot provide the reliable characteristics of different cystic pancreatic lesions. Thus, it is difficult to distinguish these tumours. Cystadenomas often consist of small cystic areas and a spoke-like pattern of fibrotic strands. In contrast, cystadenocarcinomas often show large cysts (frequently larger than 5 cm in size). Pseudocysts are frequently echo-free and have a sharply delineated wall.

The angiographic vascularization pattern contributes to the differentiation of pancreatic tumours[16-18]. Since cyst -adenomas are characterised by their hypervascularization, they are often found to be hypovascularized with a chaotic pattern. However, the diagnostic accuracy of angiography is low because it is not possible to investigate the macroscopic tumour features[17].

The vascularization of tumours may also be studied by fundamental power and colour Doppler sonography. However, the sensitivity of these procedures is low in detecting low blood flow velocity or small vessels. This sensitivity can be improved by echo-enhancers, such as SonoVue® and Levovist®. Levovist® consists of air-filled microbubbles which enhance the Doppler signal at 20-30 dB[19-21]. However, the signal intensity of echo-enhanced sonography from flowing blood is lower than that of tissue movements. To overcome these difficulties the technique of the 2nd harmonic imaging has been developed based on the property of microbubbles to resonate and emit harmonic waves in an ultrasound field with a frequency of 1-5 MHz. If the harmonic frequency is to be detected at twice the transmitted frequency, the procedure is called the 2nd harmonic imaging. Since tissue particles have fewer of the 2nd harmonic waves than microbubbles, the signals of echo-enhancers are better distinguishable[19].

The new contrast agent Sonovue® is used more frequently for echo-enhanced sonography. Furthermore, the 2nd harmonic imaging can be replaced partially by the pulse inversion imaging technique. There are observations that with this new procedure more favourable results can be achieved than with the 2nd harmonic imaging. The 2nd harmonic imaging cannot separate the transmitted and received harmonic signals completely because of limited bandwidth. However, pulse inversion imaging avoids these bandwidth limitations using characteristics specific to microbubble vibrations to subtract rather than filter out the fundamental signals. Because this imaging technique transmits two reciprocal pulses, leading to a subtraction of the two fundamental signals, it allows the use of broader bandwidths for the transmission and reception yielding an improved resolution and can provide an increased sensitivity to contrast[22]. However, comparative results of large prospective studies are missing.

We want to point out that according to our experience, conventional ultrasound, power and colour Doppler sonography, and echo-enhanced sonography should not be used as single imaging techniques, exclusively. Conventional ultrasound is the basic sonographic method, and tumour differentiation is hardly possible based on an echo-enhanced sonographic examination alone. Echo-enhanced sonography offers more diagnostic criteria than conventional ultrasound alone, but similar to the angiography it is impossible to investigate macroscopic tumour features with this procedure alone. Therefore, all sonographic procedures should be performed in combination.

The characteristic signs of pancreatic tumours at echo-enhanced sonography have been published [10,11]. Solid areas of cystadenocarcinomas and the wall of the ”old pseudocysts” are found to be hypovascularized. In contrast, solid parts of cystadenomas and the wall of the "young pseudocysts" are mostly hypervascularized. A recently published study showed that echo-enhanced sonography can differentiate cystic neoplasms better than conventional ultrasound alone[12].

The successful treatment of cystic pancreatic tumours requires a highly sensitive and specific diagnostic procedure. Echo-enhanced sonography can fulfil this requirement. However, histology is still the gold standard for the differentiation of cystic pancreatic lesions.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Cao L

References

- 1.Rall CJ, Rivera JA, Centeno BA, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, Rustgi AK. Peritoneal exfoliative cytology and Ki-ras mutational analysis in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 1995;97:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03978-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compagno J, Oertel JE. Microcystic adenomas of the pancreas (glycogen-rich cystadenomas): a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compagno J, Oertel JE. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas with overt and latent malignancy (cystadenocarcinoma and cystadenoma). A clinicopathologic study of 41 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:573–580. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;212:432–43; discussion 444-5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199010000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torresan F, Casadei R, Solmi L, Marrano D, Gandolfi L. The role of ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of serous and mucinous cystic tumours of the pancreas. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:169–172. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199702000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang EY, Joehl RJ, Talamonti MS. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:747–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Calan L, Levard H, Hennet H, Fingerhut A. Pancreatic cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: diagnostic value of preoperative morphological investigations. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickes S, Unkrodt K, Neye H, Ocran KW, Wermke W. Differentiation of pancreatic tumours by conventional ultrasound, unenhanced and echo-enhanced power Doppler sonography. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1313–1320. doi: 10.1080/003655202761020605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rickes S, Unkrodt K, Ocran K, Neye H, Wermke W. Differentiation of neuroendocrine tumors from other pancreatic lesions by echo-enhanced power Doppler sonography and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy. Pancreas. 2003;26:76–81. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200301000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rickes S, Unkrodt K, Ocran K, Neye H, Lochs H, Wermke W. [Evaluation of doppler ultrasonography criteria for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic tumors] Ultraschall Med. 2000;21:253–258. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rickes S, Flath B, Unkrodt K, Ocran K, Neye H, Lochs H, Wermke W. [Pancreatic metastases of renal cell carcinomas - evaluation of the contrast behavior at echo-enhanced power-Doppler sonography in comparison to primary pancreatic tumors] Z Gastroenterol. 2001;39:571–578. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rickes S, Wermke W. Differentiation of cystic pancreatic neoplasms and pseudocysts by conventional and echo-enhanced ultrasound. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:761–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunk A, Herzog KH, Kunze P, Braun S. [Ultrasound differential diagnostic aspects in cystadenoma of the pancreas] Ultraschall Med. 1995;16:210–217. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1003206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Borgne J, de Calan L, Partensky C. Cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas of the pancreas: a multiinstitutional retrospective study of 398 cases. French Surgical Association. Ann Surg. 1999;230:152–161. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199908000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fugazzola C, Procacci C, Bergamo Andreis IA, Iacono C, Portuese A, Dompieri P, Laveneziana S, Zampieri PG, Jannucci A, Serio G. Cystic tumors of the pancreas: evaluation by ultrasonography and computed tomography. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:53–61. doi: 10.1007/BF01887305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein HM, Neiman HL, Bookstein JJ. Angiographic evaluation of pancreatic disease. A further appraisal. Radiology. 1974;112:275–282. doi: 10.1148/112.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuter SR, Redman HC, Bookstein JJ. Differential problems in the angiographic diagnosis of carcinoma of the pancreas. Radiology. 1970;96:93–99. doi: 10.1148/96.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appleton GV, Bathurst NC, Virjee J, Cooper MJ, Williamson RC. The value of angiography in the surgical management of pancreatic disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1989;71:92–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wermke W, Gaßmann B. Tumour diagnostics of the liver with echo enhancers. doi. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer Verlag; 1998. pp. 10.1007/978–3-642-46873-5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calliada F, Campani R, Bottinelli O, Bozzini A, Sommaruga MG. Ultrasound contrast agents: basic principles. Eur J Radiol. 1998;27 Suppl 2:S157–S160. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(98)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Correas JM, Hélénon O, Pourcelot L, Moreau JF. Ultrasound contrast agents. Examples of blood pool agents. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1997;412:101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim AY, Choi BI, Kim TK, Kim KW, Lee JY, Han JK. Comparison of contrast-enhanced fundamental imaging, second-harmonic imaging, and pulse-inversion harmonic imaging. Invest Radiol. 2001;36:582–588. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200110000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]