Abstract

An association between chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) has been suggested. However, a causative role of HCV in these conditions has not been established. The authors report a case of a 50 year-old woman with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) who has been followed up since 1998 due to a high viral load, genotype 1b and moderately elevated liver function tests (LFTs). Laboratory data and liver biopsy revealed moderate activity (grade: 5/18, stage: 1/6). In April 1999, one-year interferon therapy was started. HCV-RNA became negative with normalization of LFTs. However, the patient relapsed during treatment. In September 2002, the patient was admitted for chronic back pain. A CT examination demonstrated degenerative changes. In March 2003, multiple myeloma was diagnosed (IgG-kappa, bone ma-rrow biopsy: 50% plasma cell infiltration). MRI revealed a compression fracture of the 5th lumbar vertebral body and an abdominal mass in the right lower quadrant, infiltrating the canalis spinalis. Treatment with vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone (VAD) was started and bisphosphonate was administered regularly. In January 2004, after six cycles of VAD therapy, the multiple myeloma regressed. Thalidomide, as a second line trea-tment of refractory multiple myeloma (MM) was initiated, and followed by peginterferon-α2b and ribavirin against the HCV infection in June. In June 2005, LFTs returned to normal, while HCV-RNA was negative, demonstrating an end of treatment response. Although a pathogenic role of HCV infection in malignant lymphoproliferative disorders has not been established, NHL and possibly MM may develop in CHC patients, supporting a role of a complex follow-up in these patients.

Keywords: HCV, Multiple myeloma, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Extrahepatic manifestation

INTRODUCTION

Numerous clinical syndromes have been reported in association with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Some are well established while others remain a speculation (Table 1)[1], Fourteen to seventy percent of patients with HCV have detectable cryoglobulins in their serum even in the absence of rash, weakness or arthralgias[1], whereas 50-90% of patients with mixed cryoglobulinaemia are reported to have HCV infection[2]. It is suggested that approximately 10% of type II mixed cryoglobulinaemiae can evolve into malignant lymphoma several years after diagnosis.

Table 1.

Extrahepatic diseases associated with hepatitis C virus infection

| Association: strong | Intermediate | Weak |

| -Cryoglobulinemic syndrome (Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis, arthritis, weakness) | -Porphyria cutanea tarda -Diabetes | -Thyroid disease -Corneal ulcers -Lichen planus -Pulmonary fibrosis |

| -Renal disease (membranoproliferative glomerulo- nephritis) | ||

| -Peripheral neuropathy | ||

| -Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | ||

| -Sjörgen’s syndrome |

Epidemiological studies from Europe, Japan and North America also implicate that HCV plays a role in the pathogenesis of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL)[3-7]. HCV infection is detectable in a significant proportion of NHL (14%-52%), nonetheless, it has not been confirmed[8]. A 50-fold elevation in the risk for NHL of the liver or salivary glands has been reported in an Italian case-control study, which is greater than the relative risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. The relative risk for NHL of other sites is increased about 4-fold[9]. An association between multiple myeloma (MM) and chronic HCV infection has been suggested by some epidemiological studies[2,9].

CASE REPORT

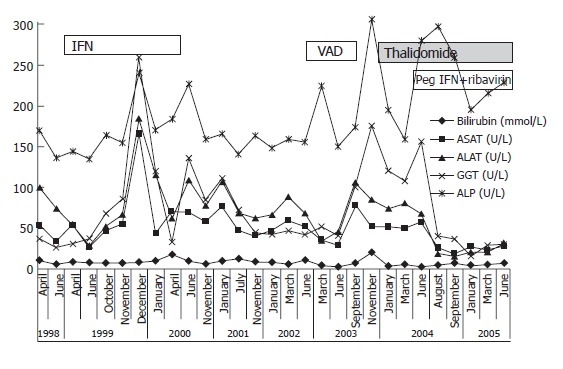

The authors report a case of a 50 year-old woman with chronic HCV infection who has been followed up since 1998 due to high viral load (13.47 MEq/mL), genotype 1b and moderately elevated liver function tests (LFTs). The patient received treatment of chronic backache and tonsillectomy prior to admission to our hospital. Laboratory data and liver biopsy revealed moderate activity (grade 5/18, stage I). In April 1999, one-year interferon therapy (3x3ME/wk) was initiated. HCV-RNA became negative with normalization of the LFTs. However, the patient relapsed in the 7th mo of treatment (HCV-RNA became positive, LFTs increased). The liver function tests are summarized in Figure 1. In February 2000, hypothyroidism was diagnosed, substitution was initiated and follow-up was scheduled.

Figure 1.

Liver function tests from April 1998 to July 2005.

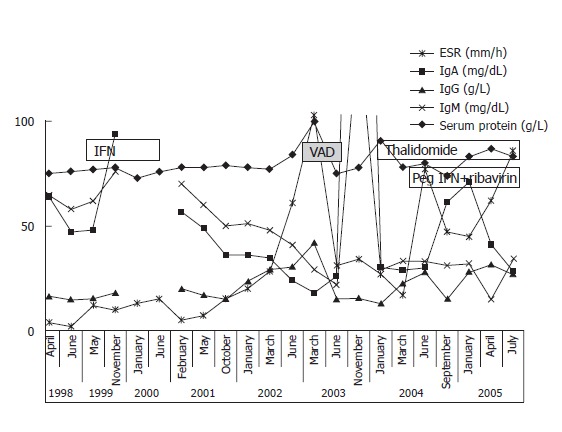

In September 2002, the patient was admitted for chronic backpain. CT examination revealed degenerative changes of the 5th lumbar vertebral body. Subsequently, the patient was not monitored until March 2003, when she was again hospitalized due to chronic backache and weakness of the right lower limb. Based on laboratory results, IgG-κ multiple myeloma was diagnosed (erythrocyte sedimentation rate; ESR): 104 mm/h, IgA: 0.18 g/L, IgG: 41.86 g/L, IgM: 0.29 g/L and 12.8% M-component on serum immunoelectrophoresis; bone marrow biopsy: 50% plasma cell infil). Mixed cryoglobulins were detected in the serum. Anemia, low platelet count or hypercalcaemia did not occur during follow-up. Serum IgG was elevated from 1998. However, monoclonality was not detected prior to March 2003. The serum immunoglobulin data and ESR are presented in Figure 2. MRI revealed a compression fracture of the 5th lumbar vertebral body and an abdominal mass in the right lower quadrant, infiltrating the canalis spinalis, ileum and sacroiliac joint (osteolytic lesions).

Figure 2.

ESR and serum immunoglobulin levels from April 1998 to July 2005.

An aggressive treatment regimen was implemented with vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone (VAD). From April to October 2003, she received six cycles of VAD therapy followed by multiple myeloma’s regression. The presence of compression fracture also prompted the regular adminis of bisphosphonate (Aredia). In January 2004, 22.2% M-components were detected by immunoelectrophoresis, yet the ESR was normal (17 mm/h). Methyl prednisolone (100 mg b.i.d) and cytoxane (100 mg o.d.) p.o. therapy was started.

In April 2004, she was admitted to the Haematological Department for paraparesis. Laminectomy (Th VII-IX) with myelin decompression and tumor resection was performed. Therapy was amended with thalidomide (100mg o.d.) orally. In August, repeated CT scans demonstrated compression fractures at L5 and S2 accompanying narrowing of the spinal canal at L5. In September, due to worsening of the paraparesis, a second laminectomy was performed (L5-S1) followed by insertion of a stabilizing prosthesis (L4-S1).

In June 2004, weekly peginterferon-α2b (1.5 μg/kg) and 800 mg ribavirin (daily) were prescribed (HCV PCR 145 000 IU/mL, Roche TaqMan). No further dose adjustment was necessary. The LFTs became normal and PCR returned negative after three months of therapy, indicating an early viral response (EVR). In June 2005, the LFTs were normal with a negative HCV-PCR, demonstrating an end of treatment response (ETR).

DISCUSSION

In recent years, major advances have been made in the treatment of HCV infection with the sustained response rate of 52%-63% achieved[11-13]. A major disadvantage in Hungary is that the hard-to-treat genotype 1 is almost universal (90%-95%) and occurs much more frequently compared to that in other European countries[13,14].

Apart from hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV infection is also associated with various extrahepatic diseases, including mixed cryoglobulinaemia and NHL. Fourteen to seventy percent of patients with HCV have detectable cryoglobulins in their serum[1,2], while 50%-90% of patients with mixed cryoglobulinaemia are reported to have HCV infection.

Epidemiological case-control studies from the 1990s suggest that chronic HCV infection is associated with the development of NHL. It was reported that 9% and 11.5% of NHL patients are HCV-antibody positive[15,16]. Germanidis et al[4] investigating 201 NHL patients found that the prevalence of HCV infection was 2-fold higher than that in controls[4]. More recent studies have further confirmed this finding. A Japanese study showed that 17% of patients with B-cell NHL were HCV-antibody positive compared to 6.6% of controls[6]. Moreover, an East European study[7] reported that 6 out of 42 (24.3%) NHL patients were HCV-antibody positive. In contrast, Rabkin et al[8] investigated the stored sera of 57 NHL patients, 24 MM patients and fourteen Hodgkin’s disease patients, and found that only four patients were HCV-antibody positive.

An association between chronic HCV infection and MM was also found in epidemiological studies. Gharagozloo et al[2] showed that HCV antigens were detectable in 11% of patients with MM, 69% of patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia and 4.3% of patients with NHL, using recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Another study revealed that HCV infection was found in 32% of MM patients[10]. The former was associated with 4.3-fold risk for MM.

The possible mechanism by which HCV infection leads to stimulation of B cells is starting to unravel. It is well documented that HCV infection, as observed in our case, usually precedes NHL by many years[9]. Hepatitis C is lymphotropic and may replicate in lymphocytes and hepatocytes[17]. The second portion of the HCV envelope (E2 protein) binds to CD81[18], suggesting that this phenomenon is associated with CD19 and CR2 as well as MHC class II molecules on lymphocytes. The binding of CD81 to B cells can activate this complex, which lowers the antigen threshold necessary for antibody stimulation, thus rendering the B cell hyper-responsive. Sequencing of the antigen-binding region of immunoglobulin produced by malignant lymphocytes demonstrates that it has a high degree of homology to both antibodies specific for E2, as well as the antibodies produced by B cells that secrete RF. Furthermore, 88% of patients with HCV infection and cryoglobulinaemia demonstrate over-expression [t(14,18)translocation] of the anti-apoptotic bcl-2 gene, compared with 8% of patients with HCV infection, 2% of patients with other liver diseases, and 3% of individuals with other rheumatoid disorders, which cause enhanced B cell survival[19]. In addition, over-expression of NF-kB has been reported in lymphocytes and liver samples of patients with chronic HCV infection and those with NHL[20,21]. This is an important finding, as NF-kB plays a key role in virus-induced lymphomagenesis. Mutations of the NF-kB gene are common in lymphoid malignancies[22] and alterations of NF-kB could initiate changes in downstream regulatory pathways. A second mutation (e.g. myc, NF-kB) could possibly initiate the progression to lymphoma[23].

In conclusion, although a pathogenic role of HCV infection in malignant lymphoproliferative disorders has not been established, NHL and possibly MM may develop in cases of CHC, supporting the need for a complex follow-up in these patients.

Footnotes

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF

References

- 1.Agnello V, De Rosa FG. Extrahepatic disease manifestations of HCV infection: some current issues. J Hepatol. 2004;40:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gharagozloo S, Khoshnoodi J, Shokri F. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Pathol Oncol Res. 2001;7:135–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03032580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnello V, Chung RT, Kaplan LM. A role for hepatitis C virus infection in type II cryoglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1490–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211193272104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Germanidis G, haioun C, Dhumeaux D, Reyes F, Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C virus infection, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Hepatology. 1999;30:822–823. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trejo O, Ramos-Casals M, López-Guillermo A, García-Carrasco M, Yagüe J, Cervera R, Font J, Ingelmo M. Hematologic malignancies in patients with cryoglobulinemia: association with autoimmune and chronic viral diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;33:19–28. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2003.50020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizorogi F, Hiramoto J, Nozato A, Takekuma Y, Nagayama K, Tanaka T, Takagi K. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Intern Med. 2000;39:112–117. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.39.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasztonyi B, Pár A, Szomor A, Nagy A, Kereskai L, Losonczy H, Pajor L, Horanyi M, Mózsik G. [Hepatitis C virus infection and B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma] Orv Hetil. 2000;141:2649–2651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabkin CS, Tess BH, Christianson RE, Wright WE, Waters DJ, Alter HJ, Van Den Berg BJ. Prospective study of hepatitis C viral infection as a risk factor for subsequent B-cell neoplasia. Blood. 2002;99:4240–4242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vita S, Zagonel V, Russo A, Rupolo M, Cannizzaro R, Chiara G, Boiocchi M, Carbone A, Franceschi S. Hepatitis C virus, non-Hodgkin's lymphomas and hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:2032–2035. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montella M, Crispo A, Russo F, Ronga D, Tridente V, Tamburini M. Hepatitis C virus infection and new association with extrahepatic disease: multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2000;85:883–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, Lee WM, Mak C, Garaud JJ, et al. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061–1069. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abonyi ME, Lakatos PL. Ribavirin in the treatment of hepatitis C. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:1315–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cenci M, De Soccio G, Recchia O. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes in central Italy. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:5129–5132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestri F, Pipan C, Barillari G, Zaja F, Fanin R, Infanti L, Russo D, Falasca E, Botta GA, Baccarani M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 1996;87:4296–4301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashyap A, Nademanee A, Molina A. Hepatitis C and B-cell lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:695. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferri C, Monti M, La Civita L, Longombardo G, Greco F, Pasero G, Gentilini P, Bombardieri S, Zignego AL. Infection of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by hepatitis C virus in mixed cryoglobulinemia. Blood. 1993;82:3701–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, Weiner AJ, Houghton M, Rosa D, Grandi G, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zignego AL, Giannelli F, Marrocchi ME, Mazzocca A, Ferri C, Giannini C, Monti M, Caini P, Villa GL, Laffi G, et al. T(14; 18) translocation in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2000;31:474–479. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tai DI, Tsai SL, Chen YM, Chuang YL, Peng CY, Sheen IS, Yeh CT, Chang KS, Huang SN, Kuo GC, et al. Activation of nuclear factor kappaB in hepatitis C virus infection: implications for pathogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology. 2000;31:656–664. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasztonyi B, Pár A, Kiss K, Kereskai L, Szomor A, Szeberényi J, Pajor L, Mózsik G. [Activation of the nuclear factor kappa B--key role in oncogenesis Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and lymphomagenesis] Orv Hetil. 2003;144:863–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neri A, Fracchiolla NS, Migliazza A, Trecca D, Lombardi L. The involvement of the candidate proto-oncogene NFKB2/lyt-10 in lymphoid malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;23:43–48. doi: 10.3109/10428199609054800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellis M, Rathaus M, Amiel A, Manor Y, Klein A, Lishner M. Monoclonal lymphocyte proliferation and bcl-2 rearrangement in essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Eur J Clin Invest. 1995;25:833–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1995.tb01692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]