Abstract

AIM: To compare the effects of Aloe vera and sucralfate on gastric microcirculatory changes, cytokine levels and gastric ulcer healing.

METHODS: Male Spraque-Dawley rats (n= 48) were divided into four groups. Group1 served as control group, group 2 as gastric ulcer group without treatment, groups 3 and 4 as gastric ulcer treatment groups with sucralfate and Aloe vera. The rats from each group were divided into 2 subgroups for study of leukocyte adherence, TNF-α and IL-10 levels and gastric ulcer healing on days 1 and 8 after induction of gastric ulcer by 20 % acetic acid.

RESULTS: On day 1 after induction of gastric ulcer, the leukocyte adherence in postcapillary venule was significantly (P< 0.05) increased in the ulcer groups when compared to the control group. The level of TNF-α was elevated and the level of IL-10 was reduced. In the ulcer groups treated with sucralfate and Aloe vera, leukocyte adherence was reduced in postcapillary venule. The level of IL-10 was elevated, but the level of TNF-α had no significant difference. On day 8, the leukocyte adherence in postcapillary venule and the level of TNF-α were still increased and the level of IL-10 was reduced in the ulcer group without treatment. The ulcer treated with sucralfate and Aloe vera had lower leukocyte adherence in postcapillary venule and TNF-α level. The level of IL-10 was still elevated compared to the ulcer group without treatment. Furthermore, histopathological examination of stomach on days 1 and 8 after induction of gastric ulcer showed that gastric tissue was damaged with inflammation. In the ulcer groups treated with sucralfate and Aloe vera on days 1 and 8, gastric inflammation was reduced, epithelial cell proliferation was enhanced and gastric glands became elongated. The ulcer sizes were also reduced compared to the ulcer group without treatment.

CONCLUSION: Administration of 20 % acetic acid can induce gastric inflammation, increase leukocyte adherence in postcapillary venule and TNF-α level and reduce IL-10 level. Aloe vera treatment can reduce leukocyte adherence and TNF-α level, elevate IL-10 level and promote gastric ulcer healing.

Keywords: Aloe vera, Sucralfate, Gastric microcircul-ation, TNF-α, IL-10, Gastric ulcer healing

INTRODUCTION

Gastric ulcer is produced by the imbalance between gastro-duodenal mucosal defense mechanism and damaging force. Impaired mucosal defense is invoked in ulcer patients with normal levels of gastric acid and pepsin. Patients chroni-cally using non-steroid anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, can be pointed with some assurance at suppression of mucosal prostaglandin synthesis. Cigar-ette smoking impairs healing and favors recurrence, possi-bly by suppressing mucosal prostaglandin synthesis. Alcohol is another agent causing gastric mucosal lesion. It rapidly penetrates the gastroduodenal mucosa causing membrane damage, exfoliation of cells and erosion[1]. Corticosteroids at a high dose and repeated use promote ulceration. Personality and psychologic stress are important contribution factors as well[2].

Gastric ulceration results from the imbalance between gastrotoxic agents and protective mechanisms result in acute inflammation. Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) are the major proin-flammatory cytokines, playing an important role in production of acute inflammation[3] accompanied with neutrophil infiltration of gastric mucosa[4].

Aloe plants have been used medicinally for centuries. Among them, Aloe barbadensis, commonly called Aloe vera, is one of the most widely used healing plants in the history of mankind[5].

Two distinct preparations of Aloe plants are most used medicinally. The leaf exudate (aloe) is used as a laxative and the mucilaginous gel (Aloe vera) extracted from the leaf parenchyma is used as a remedy against a variety of skin disorders[6]. Aloe leaf exudate also possesses antidiabetic[7] and cardiac stimulatory activity[8].

Aloe vera is one of the few substances known to effec-tively decrease inflammation and promote wound healing[9,10]. Aloe vera gel could promote the healing of burns and other cutaneous injuries and ulcer[11,12], thus improving wound healing in a dose-dependent manner and reducing edema and pain[9].

Aloe vera gel has been demonstrated to protect human beings[13-15] and rats[16-22] against gastric ulceration. This antiulcer activity is due to its anti-inflammatory[20], cytoprotective[16], healing[20,23] and mucus stimulatory effects[24].

However, the effects of Aloe vera on gastric micro-circulation, inflammatory cytokines in gastric ulcer patients have not yet been reported. Therefore, the aim of this study was to study the effects of Aloe vera and sucralfate on gastric microcirculatory changes, cytokine level and gastric ulcer healing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation

Male Spraque Dawley rats weighing 200-280 g purchased from the International Animal Research Center, Salaya (n = 48), were used in this study. Group 1 served as control group, group 2 as gastric ulcer group without treatment, groups 3 and 4 as gastric ulcer treatment groups with sucralfate (200 mg/kg/dose, twice daily) and Aloe vera (200 mg/kg/dose, twice daily).

The animals were fasted but allowed only water 12 hours before experiment. On the day of experiment, the animals were weighed and anesthetised with intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight). After tracheostomy, carotid artery and jugular vein were canulated for blood pressure measurement using polygraph and administration of fluorescent marker. The abdominal wall was incised and the stomach was extended and fixed. Then the leukocyte adherence in stomach was observed by in vivo microscopy.

Study of interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells in postcapillary venule

For visualization of leukocytes, acridine orange was infused intravenously (0.5 mg/kg BW) as previously described[25]. The number of leukocyte adhesions was recorded using video recorder. Videotape of each experiment was played back and then leukocyte adherence was monitored. The leukocytes were markedly adhered to the postcapillary venule (about 15-35 μm in diameter). The location of leukocyte adherence in three areas was observed. Leukocytes were considered adherent to the vessel endo-thelium if they remained stationary for 30 or longer. Adherent leukocytes were expressed as the mean number of leukocyte adherences per field of view as previously described[26].

Mean number of leukocyte adherences = [the number of (area 1 + area 2 + area 3) cells/field]/3

Determination of serum cytokine levels

After the experiment, blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture, allowed to clot for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 2-8 °C before centrifugation for 20 minutes at approximately 2000 r/min. Serum was separated and stored at about -80 °C for determining TNF α and IL-10 levels by ELISA kit (Quantikine, R&D systems).

Histological analysis

The stomach was fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at a thickness of 5 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) as previously described[3]. Histopathological changes and maximum length of gastric ulcer were observed under light mic-roscope with magnification × 20. Histopathological exam-ination was performed by pathologists.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was done using one-way analysis of variance and comparision of results between groups was made using post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

RESULTS

Interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells

After gastric ulcer was induced by administration of 20 % acetic acid, leukocyte adherence to endothelial cells of postcapillary venules (15-35 mm in diameter.) was observed under intravital fluorescence microscopy. The number of leukocytes adhered to postcapillary venules for 30 s or longer was counted per each field of observation. The mean number of leukocyte adherences in the ulcer group without treatment (d1: 13.13 ± 1.19 cells/field; d8: 13.61 ± 1.99 cells/field) was significantly increased compared to the control group (d1: 1.69 ± 0.17 cells/field; d8: 5.53 ± 0.65 cells/field).

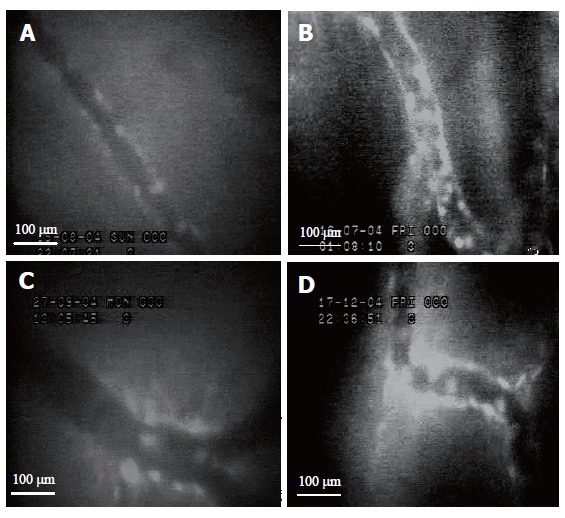

On days 1 and 8 after induction of gastric ulcer, the number of leukocyte adherences was significantly decreas-ed both in the ulcer group treated with sucralfate (d1: 3.22± 0.76 cells/field; d8: 3.80 ± 0.79 cells/field) and in the ulcer group treated with Aloe vera (d1: 4.29 ± 0.39 cells/field; d8: 4.46 ± 0.27 cells/field) (P < 0.05) compared to the ulcer group without treatment (d1: 13.13 ± 1.19 cells/field; d8: 13.61 ± 1.99 cells/field). The number of leukocyte adherences in the ulcer group treated with Aloe vera was reduced as the ulcer group treated with sucralfate. The mean ± SE of leukocyte adherences on days 1 and 8 is shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Leukocyte adherence on postcapillary venules indifferent groups (mean±SE, n=6)

| Group |

Mean leukocyte adherence (cells/field) |

|

| Day 1 | Day 8 | |

| Control | 1.69 ± 0.17 | 5.53 ± 0.65 |

| Ulcer | 13.13 ± 1.19a | 13.61 ± 1.99a |

| Ulcer+sucralfate | 3.22 ± 0.76c | 3.80 ± 0.79c |

| Ulcer+Aloe vera | 4.29 ± 0.39c | 4.46 ± 0.27c |

P < 0.05 vs control group;

P < 0.05 vs ulcer groups.

Figure 1.

Intravital microscopic (´40) images of leukocyte adherence on vascular endothelium of postcapillary venules in control group (A), ulcer group without treatment (B), ulcer groups treated with sucralfate (C) and Aloe vera (D) on day 8.

Changes of TNF-α and IL-10 levels

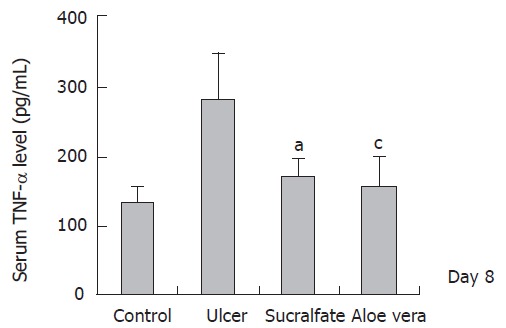

After gastric ulcer was induced by administration of 20 % acetic acid, the level of TNF-α (d1: 151.40 ± 26.87 pg/mL; d8: 280.44 ± 67.02 pg/mL) was significantly higher than that in the control group (d1: 12.51 ± 2.35 pg/mL; d8: 133.50 ± 20.95 pg/mL). However, the level of IL-10 after gastric ulcer was induced by administration of 20 % acetic (d1: 472.66 ± 167.75 pg/mL; d8: 646.60 ± 118.92 pg/mL) was significantly lower than that in control group (d1: 911.46 ± 230.81 pg/mL; d8: 883.98 ± 227.62 pg/mL). The level of TNF-α in ulcer group treated with sucralfate (138.62 ± 47.45 pg/mL) and in ulcer group treated with Aloe vera (153.02 ± 26.90 pg/mL) was higher than that in control group (12.51 ± 2.35 pg/mL) on d 1. On d 8, the level of TNF-α in ulcer group treated with sucralfate (170.21 ± 23.82 pg/mL) and in ulcer group treated with Aloe vera (154.32 ± 43.55 pg/mL) was significantly (P < 0.05) lower than that in ulcer group without treatment (280.44 ± 67.02 pg/mL) and was different from that in control group (133.50 ± 20.95 pg/mL). TNF-α level was reduced in ulcer group treated with Aloe vera as in the ulcer group treated with sucralfate.

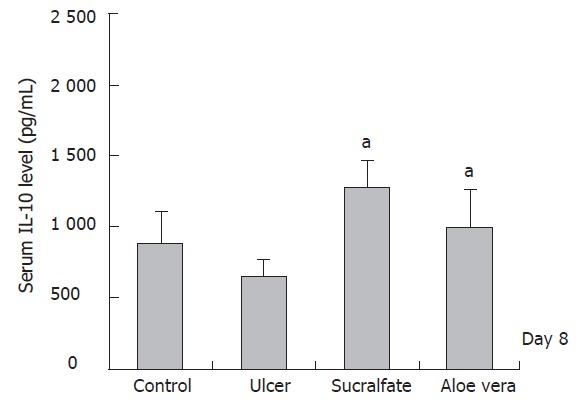

Furthermore, the level of IL-10 in ulcer group treated with sucralfate (d1: 1 419.93 ± 359.81 pg/mL; d8: 1 283.64 ± 179.72 pg/mL) and in ulcer group treated with Aloe vera (d1: 1178.13 ± 159.87pg/mL; d8: 984.02 ± 269.26 pg/mL) was higher than that in ulcer group (d1: 472.66 ± 167.75 pg/mL; d8: 646.60 ± 118.92 pg/mL) on days 1 and 8 after induction of gastric ulcer. The mean ± SE of TNF-α and IL-10 levels on d 1 and 8 is shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 2.

TNF-α level in different groups (n = 6) (mean ± SE), aP < 0.05 vs control group; CP < 0.05 vs ulcer groups.

Figure 3.

IL-10 level in different groups (n = 6) (mean±SD),cP < 0.05 vs ulcer groups.

Histopathological changes

After administration of 20 % acetic acid, histopathological examination revealed hemorrhage, congestion and edema in the gastric mucosa with mild to moderate leukocyte infiltration in gastric lesion. Gastric lesions were erosive and ulcerative. Congestion, edema and erosive lesion were found only in control group. Moreover, the mean maximum length of gastric ulcer in ulcer group without treatment (4.17 cm± 0.11 cm) was significantly longer than that in control group (3.25 cm± 0.11 cm) (P < 0.05). On day 8 after induction of gastric ulcer, control group and ulcer group without treatment had still mild congestion and edema, mild leukocyte infiltration and erosive lesion in gastric mucosa. The mean length of gastric ulcer in ulcer group without treatment (3.48 cm± 0.10 cm) was larger than that in control group (3.20 cm± 0.22 cm). On day 1, the mean maximum length of gastric ulcer in ulcer groups treated with sucralfate (3.73 cm ± 0.12 cm) and with Aloe vera (3.60 cm± 0.18 cm) became shorter after treatment when compared to the ulcer group without treatment (4.17 cm ± 0.11 cm). On day 8, the mean maximum length of gastric ulcer in ulcer groups treated with sucralfate (3.33 cm ± 0.11 cm) and Aloe vera (3.43 cm ± 0.10 cm) was slightly reduced with no significant difference after treatment when compared to the ulcer group without treatment (3.48 cm ± 0.10 cm). The mean ± S.E of the maximum length of gastric ulcer is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Maximum length of gastric ulcer (cm) in different groups (n=6) (mean±SE)

| Group |

Maximum length of gastric ulcer (cm) |

|

| Day 1 | Day 8 | |

| Control | 3.25 ± 0.11 | 3.20 ± 0.22 |

| Ulcer | 4.17 ± 0.11a | 3.48 ± 0.10 |

| Ulcer + sucralfate | 3.73 ± 0.12b | 3.33 ± 0.11 |

| Ulcer + Aloe vera | 3.60 ± 0.18b | 3.43 ± 0.10 |

aP <0.05 vs control group, bP <0.05 vs ulcer groups

DISCUSSION

In this study, after gastric ulcer was induced by admi-nistration of 20 % acetic acid, gastric inflammation in-creased leukocyte adherence to the endothelial surface of postcapillary venules and was characterized by the migra-tion of macrophages and PMNs in the ulcer area. The migrated macrophages then released proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Pro-inflammatory cytokines can up-regulate adhesion molecule expression on endothelial cells and leukocytes[27,28] and cause leukocyte recruitment[29]. Adhesion molecules on endothelial cells and leukocytes involve rolling, adhesion, and transmigration of leukocytes in gastric inflamed areas. It was reported that increment of PMNs may play an important role in the pathogenesis of NSAIDs-induced gastropathy[30]. On the other hand, NSAIDs may enhance the expression of cell adhesion molecules on the surface of endothelial cells[31]. Adhesion molecules play an important role in the recruitment of leukocytes to inflammation sites, leading to gastric mucosal injury[31,32]. It was also reported that leukocyte adhesion and/or aggregation can occlude microcirculation, resulting in ischemic mucosal injury[31,33]. Leukocyte infiltration in gastric mucosa can cause tissue damage leading the ulcerative lesion[34].

In this study, gastric ulcer induced by administration of 20% acetic acid had elevated TNF-α levels, demonstrating that elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine level induces interaction between leukocytes and endothelial cells. It was suggested that 20 % acetic acid could stimulate macrophages to release proinflammatory cytokines. TNF-α can stimulate ICAM-1 expression on vascular endothelial cells. ICAM-1 is an adhesion molecule, which plays a pivotal role in inflammatory reaction by increasing leukocyte adhesion to endothelium and promoting transen-dothelial migration of leukocytes to inflammatory sites[3]. Moreover, it was reported that TNF-α can also stimulate expression of LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18)[35], an adhesion molecule on leukocytes. This might be the reason why of TNF-α and leukocytes-endothelium interaction is increased in the inflammatory area.

However, after gastric ulcer was induced by admini-stration of 20 % acetic acid IL-10 level was reduced on day 1, but elevated spontaneously on day 8 as compared to the control groups (Figure 3). This might be due to the fact that when the gastric mucosa was damaged by acetic acid, T and B lymphoctyes in submucosal beneath the damaged area that typically produce basal level of IL-10 were also damaged. The location of macrophages was actually beyond the damaged area, therefore, the macrophages were then survived. The survived macrophages are able to stim-ulate the release of TNF-α in response to acetic acid injury. Therefore, our findings suggest that TNF-α is synthesized more than IL-10. When inflammation occurs, IL-10 is synthesized. The increment of IL-10 level reduces gastric inflammation through its feedback inhibition of TNF-α production. Therefore, IL-10 is spontaneously elevated in chronic gastric inflammation. The elevation of IL-10 then reduces gastric tissue inflammation simultaneously.

Aloe vera and sucralfate could reduce leukocyte ad-herence after gastric ulcer was induced by 20 % acetic acid. It has been reported that Aloe vera can decrease carrageenan- induced edema and neutrophil migration in rats[36]. In addition, Aloe vera has antiinflammatory effect on burn wounds by reducing leukocyte adhesion in rats[37,38]. On the other hand, Aloe vera is able to inhibit prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) and thromboxane B2 production in guinea pig with burn wounds[39]. Thromboxanes and prostaglandins (PGs) can elicit platelet aggregation, leukocyte adherence and vasoconstriction, thus enhancing ischemia. Moreover, Aloe vera possesses bradykininase activity and also decr-eases inflammation[9]. Bradykinin causes increase in vascu-lar permeability and stimulates inflammation[40]. Therefore, these effects of Aloe vera might reduce the causes of inflammatory process, the effects and leukocyte adherence after gastric ulcer is induced by 20% acetic acid.

Aloe vera and sucralfate could reduce TNF-α level on days 1 and 8 after induction of gastric ulcer (Figure 2). Aloe vera has cytoprotective effect on gastric mucosa by stimulating endogenous prostaglandins production[20]. Su-cralfate is a cytoprotective drug which also stimulates PG production. Prostaglandins (PGs), especially prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) can protect gastric mucosa from various irri-tants, promote mucus production and increase mucosal blood flow[41-43]. It was reported that PGE2 plays a role in modulating TNF-α production and is also a potent inhibitor of neutrophil adherence and chemotaxis[44]. Ding et al[45] reported that PGE2 inhibits TNF-α release in gastric mucosa and reduces in neutrophil activation and subsequently ischemia and mucosal damage. They also showed that inhibition of TNF-α by PGE2 could result in the reduction of neutrophil CD11b/CD18 and endothelial ICAM-1 expression directly or indirectly, thus subsequently reducing neutrophil adhesion on vascular wall.

In our study, Aloe vera and sucralfate could elevate IL-10 level on days 1 and 8 after induction of gastric ulcer. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by various cells including monocytes/macrophages and T lymphocyte. IL-10 can inhibit cytokine synthesis by macrophages[46]. In addition, the mild anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 may be due to the suppression of TNF-α production[47]. Bodger et al[48] showed that mucosal secretion of IL-10 and TNF-α is increased in H pylori gastritis. IL-10 may be protective and can limit tissue damage caused by inflammation. Therefore, elevation of IL-10 can down-regulate TNF-α production in macrophage.

Aloe vera and sucralfate could reduce inflammation and promote gastric ulcer healing, which has been con-firmed by histopathological examinations. Aloe vera and sucralfate promote epithelial cell proliferation, elongation and dilatation of oxyntic grand. Aloe vera and sucralfate have a cytoprotective effect on gastric mucosa by stimu-lating PGE2 production. PGE2 plays an important role in the maintenance of mucosal integrity and mucus pr-oduction. It was reported that Aloe vera could promote burn wound healing in rats[37,38,49]. In addition, Aloe vera could induce angiogenesis in vivo[5], which plays an important role in wound healing. Aloe vera can result in reduced vasoconstriction and improve perfusion of gastric mucosal capillaries, thus promoting ulcer healing[13,50,51]. Furthermore, gastric acid is considered as an important aggressive factor in the stomach and is known to produce gastric injury[52]. Aloe vera is able to decrease gastric acid secretion and increase mucus secretion[53].

The mechanism of Aloe vera could be explained by its action on inflammation and ulcer healing. The results of this study suggest that Aloe vera could decrease leukocyte adherence and TNF-α levels in inflammatory tissue. Our findings demonstrate that Aloe vera could act as an antiinflammatory agent on gastric ulcer. Our findings also indicate that ulcer healing effect of Aloe vera is mediated by increasing IL-10, an important cytokine for wound healing process.

In conclusion, Aloe vera acts on inflammation and promotes ulcer healing. Aloe vera might be used as a therapeutic agent for gastric ulcer patients.

Footnotes

Supported by Rajadapiseksompoj Research Fund, Faculty of Medicine and Research Fund by Graduate School, Chulalongkorn University

S- Editor Guo SY L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Wu M

References

- 1.Szabo S, Trier JS, Brown A, Schnoor J. Early vascular injury and increased vascular permeability in gastric mucosal injury caused by ethanol in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:228–236. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldman M, Walker P, Goldschmiedt M, Cannon D. Role of affect and personality in gastric acid secretion and serum gastrin concentration. Comparative studies in normal men and in male duodenal ulcer patients. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konturek PC, Duda A, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ, Kwiecien S, Drozdowicz D, Pajdo R, Meixner H, Hahn EG. Activation of genes for superoxide dismutase, interleukin-1beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 during healing of ischemia-reperfusion-induced gastric injury. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:452–463. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwiecień S, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Effects of reactive oxygen species action on gastric mucosa in various models of mucosal injury. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;53:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon EJ, Lee YM, Lee OH, Lee MJ, Lee SK, Chung MH, Park YI, Sung CK, Choi JS, Kim KW. A novel angiogenic factor derived from Aloe vera gel: beta-sitosterol, a plant sterol. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:117–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1009058232389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capasso F, Gaginella TS. Laxatives: a practice guide. Milan: Springer Italia; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghannam N, Kingston M, Al-Meshaal IA, Tariq M, Parman NS, Woodhouse N. The antidiabetic activity of aloes: preliminary clinical and experimental observations. Horm Res. 1986;24:288–294. doi: 10.1159/000180569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yagi A, Shibata S, Nishioka I, Iwadare S, Ishida Y. Cardiac stimulant action of constituents of Aloe saponaria. J Pharm Sci. 1982;71:739–741. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600710705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis RH, Leitner MG, Russo JM, Byrne ME. Wound healing. Oral and topical activity of Aloe vera. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1989;79:559–562. doi: 10.7547/87507315-79-11-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelton RM. Aloe vera. Its chemical and therapeutic properties. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:679–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb02607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein AD, Penneys NS. Aloe vera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:714–720. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LUSHBAUGH CC, HALE DB. Experimental acute radiodermatitis following beta irradiation. V. Histopathological study of the mode of action of therapy with Aloe vera. Cancer. 1953;6:690–698. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195307)6:4<690::aid-cncr2820060407>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.BLITZ JJ, SMITH JW, GERARD JR. Aloe vera gel in peptic ulcer therapy: preliminary report. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1963;62:731–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bovik EG. Aloe vera. Panacea or old wives' tales. Texas Detal Journal. 1966;84:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gjerstad G, Riner TD. Current status of aloe as a cure-all. Am J Pharm Sci Support Public Health. 1968;140:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahattanadul S. Antigastric ulcer properties of Aloe vera. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol. 1995;18:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galal EE, Kandil A, Hegazy R, El Ghoroury M. and Gobran W. Aloe vera and gastrogenic ulceration. J Drug Res Egypt. 1975;7:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandil A, Gobran W. Protection gastric mucosa by aloe vera. Bull Islamic Med. 1982;2:508–511. [Google Scholar]

- 19.La-angphanich S. Ulcer-healing effect of Aloe vera gel. Aloe vera whole leaf extract and cimetidine on rat gastric ulcer induced by fasting, refeeding and cortisol injection. M.Sc. Thesis in Anatomy. Bangkok: Faculty of science, Mahidol University; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert A, Nezamis JE, Lancaster C, Hanchar AJ. Cytoprotection by prostaglandins in rats. Prevention of gastric necrosis produced by alcohol, HCl, NaOH, hypertonic NaCl, and thermal injury. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:433–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maze G, Terpolilli RN, Lee M. Aloe vera extract prevents aspirin- induced acute gastric mucosal injury in rats. Med Sci Res. 1997;25:765–766. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suvitayavat W, Bunyapraphatsara N, Thirawarapan SS, Wata-nabe K. Gastric acid secretion inbititory and gastric lesion protective effects of Aloe preparation. Thai J Phytopharm. 1997;4:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teradaira R, Shinzato M, Bepp UH, Fujita K. Antigastric ulcer effects in rats of Aloe arborescens Miller var. natalensis Berger extract. Phytother Res. 1993;7:S34–S36. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visuthipanich W. Histochemical and pathological changes in rat gastric mucosa following Aloe vera gel and cortisol ad-ministration. M. Sc. Thesis in Anatomy. Bangkok: Faculty of science, Mahidol University;; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehr HA, Leunig M, Menger MD, Nolte D, Messmer K. Dorsal skinfold chamber technique for intravital microscopy in nude mice. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1055–1062. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalia N, Brown NJ, Jacob S, Reed MW, Bardhan KD. Studies on gastric mucosal microcirculation. 1. The nature of regional variations induced by ethanol injury. Gut. 1997;40:31–35. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pober JS, Bevilacqua MP, Mendrick DL, Lapierre LA, Fiers W, Gimbrone MA Jr. Two distinct monokines, interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor, each independently induce biosynthesis and transient expression of the same antigen on the surface of cultured human vascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1986;136:1680–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pohlman TH, Stanness KA, Beatty PG, Ochs HD, Harlan JM. An endothelial cell surface factor(s) induced in vitro by lipopolysaccharide, interleukin 1, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases neutrophil adherence by a CDw18-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 1986;136:4548–4553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watanabe T, Arakawa T, Fukuda T, Higuchi K, Kobayashi K. Role of neutrophils in a rat model of gastric ulcer recurrence caused by interleukin-1 beta. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:971–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morise Z, Komatsu S, Fuseler JW, Granger DN, Perry M, Issekutz AC, Grisham MB. ICAM-1 and P-selectin expression in a model of NSAID-induced gastropathy. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G246–G252. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.2.G246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace JL, McKnight W, Miyasaka M, Tamatani T, Paulson J, Anderson DC, Granger DN, Kubes P. Role of endothelial adhesion molecules in NSAID-induced gastric mucosal injury. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:G993–G998. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace JL, Arfors KE, McKnight GW. A monoclonal antibody against the CD18 leukocyte adhesion molecule prevents indomethacin-induced gastric damage in the rabbit. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:878–883. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90259-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews FJ, Malcontenti-Wilson C, O'Brien PE. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on LFA-1 and ICAM-1 expression in gastric mucosa. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G657–G664. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.4.G657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wada K, Kamisaki Y, Kitano M, Kishimoto Y, Nakamoto K, Itoh T. A new gastric ulcer model induced by ischemia-reperfusion in the rat: role of leukocytes on ulceration in rat stomach. Life Sci. 1996;59:PL295–PL301. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dustin ML, Springer TA. T-cell receptor cross-linking transiently stimulates adhesiveness through LFA-1. Nature. 1989;341:619–624. doi: 10.1038/341619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vázquez B, Avila G, Segura D, Escalante B. Antiinflammatory activity of extracts from Aloe vera gel. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;55:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Somboonwong J, Thanamittramanee S, Jariyapongskul A, Patumraj S. Therapeutic effects of Aloe vera on cutaneous microcirculation and wound healing in second degree burn model in rats. J Med Assoc Thai. 2000;83:417–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duansak D, Somboonwong J, Patumraj S. Effects of Aloe vera on leukocyte adhesion and TNF-alpha and IL-6 levels in burn wounded rats. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2003;29:239–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heggers JP, Loy GL, Robson MC, Del Beccaro EJ. Histological demonstration of prostaglandins and thromboxanes in burned tissue. J Surg Res. 1980;28:110–117. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(80)90153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu XF, Hayashi M, Yamaki K, Oh-ishi S. Assessment of vascular permeability increase in the mouse by dye leakage during paw edema. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1990;52:500–503. doi: 10.1254/jjp.52.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollander D. Gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Am J Med. 1994;96:274–281. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallace JL, McKnight GW, Bell CJ. Adaptation of rat gastric mucosa to aspirin requires mucosal contact. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:G134–G138. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.1.G134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linder JD, Mönkemüller KE, Davis JV, Wilcox CM. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib: a possible cause of gastropathy and hypoprothrombinemia. South Med J. 2000;93:930–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watanabe S, Kobayashi T, Okuyama H. Regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor alpha production by endogenous prostaglandin E2 in rat resident and thioglycollate-elicited macrophages. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1994;10:283–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding SZ, Lam SK, Yuen ST, Wong BC, Hui WM, Ho J, Guo X, Cho CH. Prostaglandin, tumor necrosis factor alpha and neutrophils: causative relationship in indomethacin-induced stomach injuries. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;348:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ribbons KA, Thompson JH, Liu X, Pennline K, Clark DA, Miller MJ. Anti-inflammatory properties of interleukin-10 administration in hapten-induced colitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;323:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bodger K, Wyatt JI, Heatley RV. Gastric mucosal secretion of interleukin-10: relations to histopathology, Helicobacter pylori status, and tumour necrosis factor-alpha secretion. Gut. 1997;40:739–744. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.6.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis RH, Donato JJ, Hartman GM, Haas RC. Anti-inflammatory and wound healing activity of a growth substance in Aloe vera. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1994;84:77–81. doi: 10.7547/87507315-84-2-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grindlay D, Reynolds T. The Aloe vera phenomenon: a review of the properties and modern uses of the leaf parenchyma gel. J Ethnopharmacol. 1986;16:117–151. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(86)90085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barry LR. Possible mechanism of the healing action of Aloe vera gel. Cosmetic and Toileteries. 1983:98. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brzozowski T, Konturek PC, Konturek SJ, Drozdowicz D, Kwiecieñ S, Pajdo R, Bielanski W, Hahn EG. Role of gastric acid secretion in progression of acute gastric erosions induced by ischemia-reperfusion into gastric ulcers. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;398:147–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suvitayavat W, Sumrongkit C, Thirawarapan SS, Bunyapraphatsara N. Effects of Aloe preparation on the histamine-induced gastric secretion in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]