Abstract

Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis (AIP) is increasingly being recognized worldwidely, as knowledge of this entity builds up. Above all, AIP is a very attractive disease to clinicians in terms of its dramatic response to the oral steroid therapy in contrast to ordinary chronic pancreatitis. Although many characteristic findings of AIP have been described, definite diagnostic criteria have not been fully established. In the year 2002, the Japan Pancreas Society published the diagnostic criteria of AIP and many clinicians around the world use these criteria for the diagnosis of AIP. The diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society, however, are not completely satisfactory and some groups use their own criteria in reporting AIP. This review discusses several potential limitations of current diagnostic criteria for this increasingly recognized condition. The manuscript is organized to emphasize the need for convening a consensus to develop improved diagnostic criteria.

Keywords: Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis, Diagnostic criteria

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis (AIP) can be defined as a chronic inflammation of the pancreas due to an autoimmune mechanism; autoimmunity is responsible for producing the pancreatic lesion[1,2]. AIP is a distinctive type of chronic pancreatitis that shows reversible improvement of pancreatic morphology and function with oral steroid therapy, in comparison to other types of chronic pancreatitis which hardly respond to various treatments[1-5].

AIP is increasingly being recognized to be a worldwide entity[6-8]. The sudden increment in cases reported probably reflects the growing awareness of the entity, rather than a rise in the true incidence. The diagnosis of AIP is, however, still challenging. Many groups have cited the diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society (Table 1)[9], whereas some groups have used their own criteria in reporting AIP[1,2,4,5,10]. This makes it difficult to compare studies from different centers, judge the relevance of comparisons and establish evidence on AIP. Above all, the largest problem was that a substantial portion of patients revealed clinical findings compatible to AIP and even responded to the steroid, yet failed to fulfill the Japanese diagnostic criteria[11,12]. This review revisits currently used diagnostic criteria of AIP focusing on the Japanese ones, discusses the potential limitation of diagnostic criteria and raises some important issues related to the diagnosis of AIP. In view of our experiences of a relatively small cohort of 28 patients, we propose a new revision that may help physicians diagnose AIP. By revising the diagnostic criteria of AIP, more patients may benefit from this diagnosis and be spared from burdensome surgery.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis by the Japan Pancreas Society

| Diagnostic criteria | |

| I | Imaging criterion: Diffuse narrowing of the main pancreatic duct with irregular wall (more than 1/3 length of the entire pancreas) and enlargement of the pancreas |

| II | Laboratory criterion: Abnormally elevated levels of serum gamma-globulin and/or IgG, or the presence of autoantibodies |

| III | Histopathologic criterion: Marked lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and dense fibrosis |

| For diagnosis, criterion I must be present, together with criterion II and/or III | |

OUR EXPERIENCES

We reviewed the clinical, radiologic, laboratory and histologic features of 28 patients with AIP who responded to the oral corticosteroid. The response to the steroid was defined as improvement in clinical symptoms, negative conversion of detected autoantibodies, normalization of elevated level of IgG or IgG4, and reversion of abnormal pancreatic imaging including CT and endoscopic retrograde pancreatogram.

The diagnosis of AIP in our hospital was made by the criteria as shown in Table 2. For the diagnosis of AIP, imaging criterion (CT and ERCP findings) was an essential component. If the patient fulfilled the imaging criterion (diffuse enlargement of pancreas and diffuse or segmental irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct) together with laboratory and/or histopathologic criteria, the patient was diagnosed of AIP. Even though a patient fulfilled imaging criterion only, in other words, the laboratory criterion and histopathologic criterion were incompatible or not available, steroid was administered and the patient was diagnosed as AIP if the response to the steroid was shown.

Table 2.

Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis in Asan Medical Center

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Criterion I. Pancreatic imaging (essential) |

| (1) CT: Diffuse enlargement (swelling) of pancreas and (2) ERCP: Diffuse or segmental irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct |

| Criterion II. Laboratory findings |

| (1) elevated levels of IgG and/or IgG4 or (2) detected autoantibodies |

| Criterion III. Histopathologic findings |

| Fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration |

| Criterion IV. Response to the steroid |

| Definite diagnosis: Criterion Iand any of criterion II-IV |

The patients’ mean age was 55.3 years (range, 32-78 years) and they were comprised of 22 males and 6 females. None of the patients had a history of alcohol abuse or other predisposing factors for chronic pancreatitis.

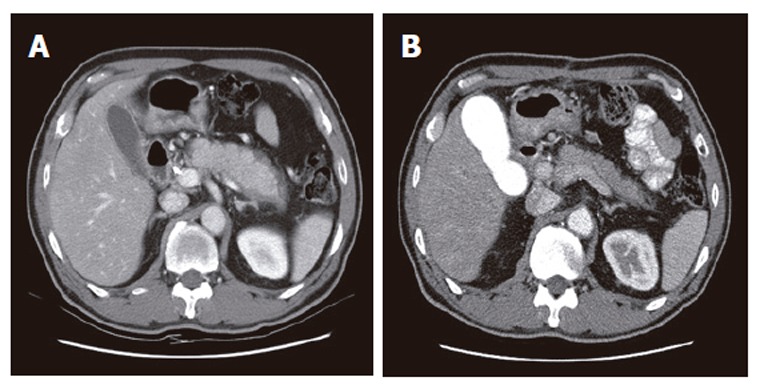

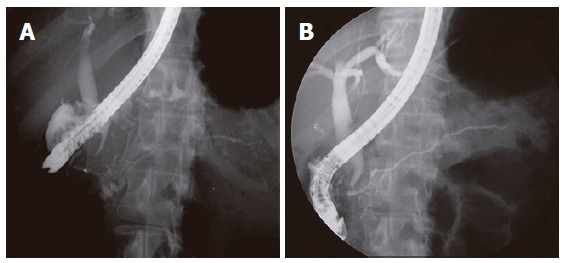

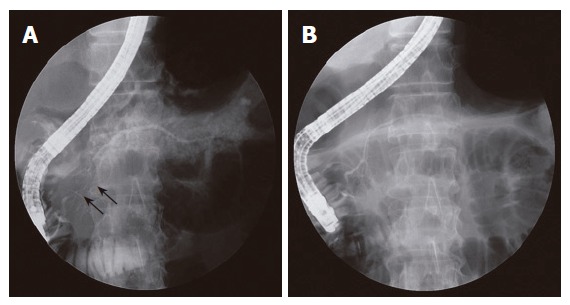

On CT, all the patients revealed a diffusely enlarged pancreas with no or mild peripancreatic fat infiltration. All the patients had no any typical findings of ordinary chronic pancreatitis, such as multiple parenchymal calcifications or pancreatic ductal stones. Capsule-like low-density rim surrounding the pancreas was shown in five (18%) patients (Figure 1). On direct pancreatogram, 8 (29%) patients showed diffuse irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct which involved entire main pancreatic duct or at least more than 2/3 of entire length of main pancreatic duct (Figure 2). In seven patients with segmental irregular narrowing, total length of ductal involvement was less than 2/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct and it was between 1/4 and 1/3 (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT findings. A: Diffusely enlarged pancreas without any calcification or stones in a 59 year-old man. A capsule-like low-density rim can also be seen around the pancreas; B: After steroid therapy, the pancreas returned to its normal size and the rim disappeared.

Figure 2.

ERCP findings. A: Diffuse irregular narrowing of more than 2/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct noted in the 49 year-old woman; B: After steroid therapy, evidently widening of the main pancreatic duct.

Figure 3.

ERCP findings. A: Segmental narrowing (arrows) of the main pancreatic duct noted at the pancreatic head. The extent of irregular narrowing is less than 1/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct; B: Direct pancreatogram revealing a normal-appearing main pancreatic duct following steroid therapy.

The IgG level was increased (>1 800 mg/dL) in 14 (50%) patients (Table 3). The IgG4 level was measured in 23 patients and it was increased in 15 (65%) patients. In 4 patients, the IgG4 level was increased without elevation of IgG level. Autoantibody was detected in 15 (68%) patients.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of 28 patients with autoimmune chronic pancreatitis

| Age/sex | Other autoimmune diseases | IgG (mg/dL) | IgG4 (mg/dL) | Auto antibody | ERCP | CT findings | Pancreas pathology | Response to steroid |

| 54/M | + | 3 570 | 1 764 | - | S | DE | N-C | Y |

| 60/M | + | 4 500 | 810 | + | S | DE | N-C | Y |

| 32/M | - | 97 | 13 | - | S | DE | ND | Y |

| 68/M | - | 2 010 | 350 | - | S | DE | Diagnosticb | Y |

| 52/M | + | 1 440 | 32 | + | S | DE | ND | Y |

| 59/M | - | 1 880 | 324 | - | S | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 53/M | + | 1 990 | 150 | + | S | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 56/F | - | 2 730 | 1 464 | + | Sa | DE | N-C | Y |

| 74/M | - | 2 210 | N-C | - | S | DE | N-C | Y |

| 52/M | - | 2 100 | N-C | - | D | DE | N-C | Y |

| 53/F | - | 1 240 | 29 | - | Sa | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 45/M | - | 1 470 | N-C | + | D | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 58/M | - | 4 100 | 780 | + | S | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 63/F | - | 1 200 | 10 | - | D | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 61/M | - | 1 500 | 190 | - | Sa | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 63/M | - | 1 780 | 658 | + | Sa | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 49/F | - | 2 000 | 445 | + | D | DE | N-C | Y |

| 59/M | - | 1 230 | 840 | + | D | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 51/M | - | 1 570 | 310 | - | D | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 68/M | + | 3 550 | 1 360 | + | S | DE | N-C | Y |

| 33/M | - | 1 350 | 66 | - | Sa | DE | N-C | Y |

| 36/M | - | 1 060 | 50 | + | D | DE | ND | Y |

| 60/M | - | 1 930 | N-C | + | Sa | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 64/F | - | 1 470 | N-C | + | S | DE | NDc | Y |

| 70/M | + | 1 820 | 310 | + | D | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 44/M | - | 1 110 | 36 | - | S | DE | Diagnostic | Y |

| 34/F | + | 1 070 | 11 | - | S | DE | ND | Y |

| 78/M | - | 4 570 | 1 580 | + | Sa | DE | N-C | Y |

S: Segmental irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct; D: Diffuse irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct; DE: Diffuse enlargement of pancreas; N-C: Not checked; ND: Non-diagnostic;

: Extent of irregular narrowing was less than 1/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct;

: Lymphoplasma cell infiltration and fibrosis;

: Eosinophilic infiltration.

Pancreatic tissue specimens were obtained from 19 patients. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided core biopsy with an 18-gauge needle was performed in 17 patients and open biopsy in 2 patients. The biopsy specimen of 14 (74%) patients showed marked inflammatory infiltrates mostly of lymphocytes and plasma cells and dense fibrosis of the pancreatic tissue. However, one patient showed predominant eosinophilic granulocytes infiltrating into the pancreatic parenchyma rather than lymphoplasma cell infiltration. Overall, the biopsy findings were non-diagnostic, that is, either lymphoplasma cell infiltration or fibrosis was minimal or absent, in 5 of 19 (26%) cases.

Seven of 28 (25%) patients who responded to the steroid did not satisfy the Japanese imaging criterion because the extent of ductal narrowing was less than one third of entire length of main pancreatic duct. Another two patients showed normal IgG level, negative results of autoantibody measurements and non-diagnostic pancreatic histopathology. Taken together, 9 of 28 (32%) patients did not meet the Japanese diagnostic criteria for AIP, yet responded to the steroid.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The diagnosis of an autoimmune disease is always an impetus to the clinician. Autoimmune conditions often lack pathognomonic findings on histopathology. The sensitivity and specificity of serologic markers also leave controversies in the diagnosis. To overcome these problems, combinations of common clinicopathologic findings are often used to guide physicians in diagnosing autoimmune diseases.

During the past decade, Japanese investigators have described many common clinicopathologic findings of AIP by reporting over three hundred cases domestically. Based on this experience, the Japan Pancreas Society published the “Diagnostic Criteria for Autoimmune Pancreatitis” in the year 2002[9]. The criteria are constituted of 3 components: (1) Pancreatic imaging: diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct with irregular wall (more than 1/3 length of the entire pancreas) and diffuse enlargement of the pancreas; (2) Laboratory data: elevated levels of serum gammaglobulin and/or IgG, or the presence of autoantibodies; and (3) Histopathologic findings: fibrotic changes with lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration. For the diagnosis of AIP, criterion 1 must be present, together with criterion 2 and/or 3 (Table 1). Interestingly, the criteria does not include symptoms or common laboratory findings, as they are not specific to AIP[13,14]. The condition commonly manifests as obstructive jaundice, weight loss, and recent-onset diabetes in elderly men. None of the patients diagnosed as AIP have a history of alcohol abuse or other predisposing factors for chronic pancreatitis. In contrast to other types of pancreatitis, severe abdominal pain is infrequently encountered. These features are similar to that of pancreaticobiliary malignancies, which are the most difficult and important entities to differentiate from AIP[15].

Imaging criterion

Radiologic imaging of the pancreas is an essential component of the Japanese criteria where it is mentioned as a “must” for diagnosing AIP. The criterion is stated as diffuse narrowing of the main pancreatic duct with irregular wall (more than 1/3 length of the entire pancreas) and diffuse enlargement of the pancreas which can be identified with ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) and CT, respectively[9]. Although abdominal US is most frequently performed imaging method for the screening of pancreatic disease, overlying bowel gas or obesity often hinders the sonographic visualization of the pancreatic gland, rendering the examination limited in scope and quality.

On CT, most cases of AIP reveal a diffusely enlarged pancreas with no or mild peripancreatic fat infiltration. Phlegmonous changes of the pancreas, peripancreatic fluid collection or pseudocysts formation are rare. Diffuse enlargement of the pancreas correlates with the pathology of marked stromal edema, which manifests as diffuse swelling on gross examination[16,17]. Surprisingly, CT does not reveal any typical findings of chronic pancreatitis, such as multiple parenchymal calcifications or pancreatic ductal stones. Rather, AIP resembles mild form of acute pancreatitis according to Balthazar classification[18]. Some cases of AIP reveal peculiar CT findings, such as a capsule-like low-density rim surrounding the pancreas (Figure 1)[19]. This rim is thought to correspond to the histologic findings of an inflammatory process that contains fibrous changes involving the peripancreatic adipose tissue[20]. Delayed enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma is another distinguishing feature of AIP. On arterial enhanced phase, the pancreas appears hypodense when compared to the spleen. On the delayed phase, attenuation increases when compared to early images. This reflects fibrosis with an associating inflammatory process. These characteristic patterns observed on CT are important in differentiating AIP from pancreatic cancer[15].

The term “enlargement” of the pancreas can be subjective and vague. The size of the pancreas may be affected by many factors, including body mass, ethnic group, gender and age. There are individual variations in the size of the gland, with smaller atrophic glands seen in older individuals[21,22]. While a pancreas may seem normal for a large young man, the same size can be described as “enlarged” for an elderly patient with small body mass. Nishino et al[23], therefore, describe that the pancreas is considered to be enlarged when the width of the pancreatic body or tail was more than two thirds of the transverse diameter of the vertebral body or the width of the pancreatic head is more than the full transverse diameter of the vertebral body.

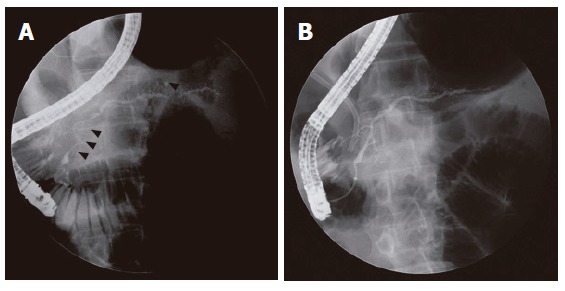

The Japanese imaging criterion has described the ductal pathology as diffuse narrowing of the main pancreatic duct with irregular wall (more than one third of the length of the entire pancreas), which can be observed on direct pancreatogram[9]. However, we were confronted with confusion when applying this criterion. This may be because the terms used were imprecise and vague in the meaning. First, in the previous international symposium on chronic pancreatitis[24,25], pancreatic lesion was classified as focal, segmental, or diffuse according to the extent of involvement. In this international classification, “diffuse” is used when a process involves the entire pancreatic duct or at least more than two-thirds of the entire length of the main pancreatic duct, whereas lesions that are not continuous and involve the head, body or tail are defined as “segmental” (Figures 2 and 4)[24,25]. In Japanese criteria, the terms “diffuse” and “at least one third of the entire length” in the same sentence are contradictory to each other. Thus, it may be more appropriate that the term “diffuse” irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct in Japanese imaging criterion (Table 1) is changed to “diffuse or segmental” irregular narrowing. In AIP cases of segmental involvement, the intervening normal-appearing duct upstream to the stricture shows no or minimal dilatation in spite of the long stricture (Figure 4). These findings differentiate AIP from pancreatic cancers, which reveal stricture associated with marked upstream ductal dilatation[26,27]. Second, “narrowing” of the main pancreatic duct is a term based on subjective assessment. At the present time, there are no references for how thin “narrowing” is. Like the size of pancreatic gland, duct diameter also varies by age, gender, and size of patient, etc. In the cases of AIP, most patients are elderly, which complicates matters because the diameter of the main pancreatic duct physiologically increases with age[28,29]. In patients with AIP, the ductal diameter widens to normal caliber after steroid therapy (Figures 2 and 4).

Figure 4.

ERCP findings. A: Segmental irregular narrowing (arrow heads) of the main pancreatic duct that involves the pancreatic head and tail portion is noted in a 53-year-old man; B: After steroid therapy, the narrowing sites on preceding ERCP were resolved. Biliary stenting for narrowing of intrapancreatic common bile duct is noted.

Some authors suggested that as a Japanese length criterion of direct pancreatogram, “more than 1/3” of ductal narrowing (Table 1) should be changed to “more than 1/4” because the extent of ductal narrowing was between 1/4 and 1/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct in some cases of AIP[30]. Actually, in our series, the extent of irregular narrowing was less than 1/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct in 7 of 28 (25%) patients (Figure 3, Table 3). Moreover, a variant form of AIP that is characterized by focal parenchymal swelling with a localized short stenosis of the main pancreatic duct and evident upstream dilatation has been reported[31]. Because this focal type is a rare form of AIP and mainly diagnosed after laparotomy, further discussion is beyond the scope of this review. However, studies reported that segmental narrowing progressed to diffuse narrowing on serial ERCPs without steroid treatment[32,33]. In other words, “focal” and “segmental” types can evolve into “diffuse” with time, which implies that the total length of the stricture can be less than one third at an earlier stage of the disease[32,33]. Last, “irregular wall” is another confusing term. While Japanese criteria use the term of “irregular” to portray the marginal irregularity of the narrowed ductal wall[30], we have experienced AIP patients with direct pancreatograms that reveal smooth margins not uncommonly. This may be related to the fact that pathologic specimens often reveal inflammation confined to the subepithelial space with an intact ductal epithelial lining[34,35]. Therefore, the term “irregular wall” may not always be appropriate for AIP. On the other hand, the Cambridge classification for chronic pancreatitis uses “irregular” (i.e., ‘irregular dilatation’ of main pancreatic duct) to describe the overall contour of the main pancreatic duct[24]. These pancreatographic findings may be explained by the heterogenous pattern of inflammatory infiltrates and fibrosis noted in pathology[34].

The intriguing point of imaging is that CT findings resembling mild acute pancreatitis are quite unusual when associating ERCP findings, which reveal diffuse or segmental irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct, are considered. Narrowing of the main pancreatic duct with or without intrapancreatic common bile duct stenosis on ERCP is a finding that is rarely seen in acute pancreatitis, but often in chronic pancreatitis[36]. While diffuse enlargement without calcification or stone is common in acute pancreatitis, this finding is rare in chronic pancreatitis and parenchymal atrophy is more frequently observed in ordinary chronic pancreatitis. CT findings have no evident chronic parenchymal changes in contrast to the ductal pathology detected on ERCP[37]. Coexistence of such contradicting radiologic findings (CT and ERCP) in the same patient was a rare yet peculiar association that was consistently observed in patients with AIP[38].

We believe that clinicians should vigorously obtain direct pancreatograms when patients show unusual clinical features or atypical clinical manifestation in patients suspected of pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Although direct pancreatogram holds a critical position in diagnosing AIP, hardships follow in obtaining it. Due to the possible risk related to the procedure, the visualization of pancreatic duct is not always carried out when the main pancreatic duct is not dilated on US or CT in patients with diffuse pancreatic swelling alone[39,40]. There are also pitfalls in interpreting pancreatograms. Because the main pancreatic duct is extrinsically compressed, it is technically difficult to attain whole ductal images and, sometimes, sufficient amount of contrast is not introduced into the main pancreatic duct. An “abrupt cutoff” of the main pancreatic duct may conceal a true “irregular narrowing” when ERCP is performed inadequately. Deep cannulation of catheter up to the tail portion guided by a thin guide wire can help circumvent this problem. While magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is replacing diagnostic ERCP in many pancreaticobiliary diseases, it seems to be limited in delineating the detailed pathology of main pancreatic duct associated with AIP. AIP is basically a “narrow-duct” disease and the resolution of MRCP is inferior to that of ERCP in this aspect[41,42].

Laboratory criterion

Abnormally elevated levels of serum gamma globulin and/or IgG or the presence of autoantibodies are described as the laboratory criterion of AIP by the Japan Pancreas Society[9]. In general, these features are known facets of autoimmune diseases, which provide laboratory evidence of an autoimmune pathogenesis[43]. By measuring various autoantibodies, a number of candidates have emerged for clinical usage in AIP. Detection rates for autoantibodies, however, have varied among reports[44,45]. This difference may be accounted by the number of measured autoantibodies, which can affect detection rates of autoantibodies; rates tend to increase as more autoantibodies are checked[46]. Among the conventional autoantibodies that are commonly investigated in autoimmune diseases, anti-nuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor are more frequently detected in AIP. Other markers, including anti-smooth muscle antibody and anti-mitochondrial antibody, have failed to show detection rates above 10%. On the other hand, anti-lactoferrin antibody (ALF) and anti-carbonic anhydrase II antibody (ACAII) are relatively organ-specific autoantibodies, which reveal the highest detection rates (over 50%) among autoantibodies in AIP[47]. Lactoferrin is normally present in the pancreatic acinus and carbonic anhydrase II in the ductal cells of the pancreas. ALF and ACA II, however, require a special laboratory for measurement that is unavailable to many clinicians. And, even if ALF and ACA II are measured, these markers are not 100% sensitive[48,49]. This implies that although carbonic anhydrase II and lactoferrin are considered to be the most likely target antigen for AIP, cases without ALF and ACAII, despite a good response to steroid therapy, also exist. ALF and ACAII are not specific to AIP as they may be elevated in other diseases[48,49]. Elevated levels of ACAII were also reported in patients with pancreatic cancer or ordinary chronic pancreatitis[10,50,51].

Elevated IgG and hypergammaglobulinemia are not always seen in patients with AIP. IgG4, a subtype of IgG, levels have been reported to be able to distinguish AIP from other pancreatic disorders with a high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (97%)[52]. Moreover, some cases of AIP show elevated serum levels of IgG4 in spite of normal IgG levels[53]. We, therefore, believe that both IgG and IgG4 levels should be measured in all patients suspected with AIP. In Japanese criteria, however, the increased IgG4 level was not included in the laboratory criteria and only mentioned in the appendix that there are cases with elevated levels of IgG4[9]. The Japanese criteria for laboratory data states that IgG levels should be higher than 1 800 mg/dL (normal range, 614-1295 mg/dL[54]). Although cutoff value of IgG was set at 1 800 mg/dL in Japanese criteria, another group uses different cutoff value (1 700 mg/dL) of IgG for the diagnosis of AIP[55]. If we set cutoff value of IgG at higher level, the specificity of IgG increases but the sensitivity decreases. More evidence on sensitivity and specificity according to each cutoff value should be provided for IgG before cutoff level is established.

While serologic markers have provided a base in understanding AIP, there are still controversies. As autoantibodies and IgG can rise non-specifically during the course of various injuries and diseases, the mere increment can not indicate a cause-and-effect relationship. Moreover, elevation of IgG4 level has been reported in patients suffering from pancreatic carcinoma and other types of chronic pancreatitis[50]. A number of groups have tried to find other laboratory indicators of AIP. HLA may identify patients susceptible to AIP. One report mentioned that frequencies of DRB1*0405 and DQB1*0401 were significantly higher in patients with AIP when compared with chronic calcifying pancreatitis[56]. At the present time, however, further studies are required to evaluate the value of each laboratory indicator and find a more reliable one.

Histopathologic criterion

The Japanese criteria described the histopathologic findings of AIP as marked inflammatory infiltrates mostly of lymphocytes and plasma cells and dense fibrosis of the pancreatic tissue[9]. In one report, however, lymphoplasma cell infiltration was minimal in one third of AIP cases. In general, marked infiltration of inflammatory cells is noted in early stage of an autoimmune disease, but fibrosis becomes predominant as the disease progresses. This suggests that degree of inflammatory cell infiltrates and fibrosis and predominance of either one may be dependent on the stage of AIP[57]. The characteristic lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis may not be pathognomonic to AIP. Alcoholic chronic pancreatitis (ACP) also showed an abundant amount of lymphoplasma cell infiltration and fibrosis[58]. Although periductal inflammation and fibrosis were observed in both ACP and AIP, the detailed histologic patterns differed. While ACP mainly revealed dense interlobular fibrosis with a cirrhosis-like appearance, AIP showed loose fibrosis in both interlobular and intralobular region[58-60]. AIP showed more severe and diffuse acinar atrophy than ACP. As for extracellular matrix proteins, collagen type IV, a component of the intact basement membrane that ensures accurate regeneration of tissue, was preserved in cases associated with AIP, whereas ACP showed a significant loss of this collagen subtype[58]. Not only may this help differentiate AIP from ACP, but also aid our understanding of the regeneration of acinar structures and regression of fibrosis following steroid treatment. More specific histologic features, i.e., the pattern of fibrosis and inflammation, should be supplemented for histopathologic criterion of AIP.

Periductal fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrates surrounding the duct like a cuff compress the ductal lumen into a star-like structure[61]. Intrapancreatic portion of common bile duct is often involved and the biliary involvement in AIP develops by the same mechanism as the pancreatitis[23]. Some reports of AIP show predominant neutrophilic or eosinophilic granulocytes infiltrating into the pancreatic parenchyma rather than lymphoplasma cell infiltration[62]. This acute inflammatory component of AIP is characterized by focal detachment, disruption and destruction of the duct epithelium due to invading granulocyte, which has been named “granulocytic-epithelial lesions” of the ducts. The extension and severity of chronic and acute changes in AIP vary from case to case, and even from area to area within the same pancreas.

Many clinicians come across difficulties in obtaining adequate pancreatic specimens for histologic evaluation[48]. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy often fails to gain sufficient amounts of pancreatic tissue. Large-bore needle biopsies may be used to yield adequate amounts for pathologic examinations. However, this is at the cost of increasing risks of procedure-related complications. Because of the patchy nature of inflammation seen in AIP, percutaneous biopsy may not be diagnostic due to sampling error problems[13]. Another problem is the potential risk of tumor seeding during biopsy in patients in whom cancer can not be omitted. Due to this reason, endoscopic ultrasonogram (EUS)-guided biopsy is recommended for patients in whom pancreatic cancer can not be excluded[63]. This approach is useful because the pancreatic head is the most frequently involved portion in AIP. One recent paper has reported the usage of EUS-guided trucut biopsy, which may help surmount the above problems and allow optimal histologic examination in AIP[64].

Although histologic evaluation offers a gold standard in diagnosing many disease entities, its role maybe a little different in autoimmune conditions, as seen in primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis[65,66]. In these conditions, the histopathologic findings are not disease-specific. Biopsy is often performed to exclude other entities that coexist or show resemblance rather than to make a diagnosis. Taken together, the role of histopathologic examination in patients suspected of AIP may be the exclusion of other diseases, such as malignancy, rather than the confirmation of diagnosis.

Response to the steroid

Although the dramatic response to the steroid is a well-known phenomenon in AIP, a detailed steroid schedule has not been fully established at the present time. Prednisolone is usually initiated at 30-40 mg per day and tapered after confirmation of the response to the steroid. The response to the steroid is defined as improvement in clinical symptoms, negative conversion of detected autoantibodies, normalization of elevated levels of IgG, and reversion of abnormal pancreatic imaging, including CT and endoscopic retrograde pancreatography[58]. In cases of obstructive jaundice associated with intrapancreatic common bile duct narrowing, however, biliary stenting is often needed additionally. The dose of oral corticosteroid may be tapered by 5 mg each 2-4 wk. Eventually, the steroid is completely discontinued or maintained at a dose of 2.5-10 mg/d according to the preference of the doctor[50,52,67].

The response to the oral steroid provides a circumstantial evidence of underlying autoimmune pathogenesis[68]. Among the responses to the oral steroid therapy, recovery of pancreatic ductal narrowing is top priority in the differential diagnosis of AIP. For the recovery of pancreatic ductal narrowing, histologic recovery including periductal fibrosis should be accompanied. We already reported histologic recovery, especially regression of pancreatic fibrosis in patients with AIP after steroid therapy[69]. Relief of pancreatic ductal narrowing by steroid administration is a unique and specific finding that can not be seen in any other type of chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer (unpublished observation, Myung-Hwan Kim, MD). And, because marked improvement of pancreatic ductal narrowing can be observed at as early as 2 wk after steroid therapy[32,50], steroid trial may be a practical diagnostic tool that has clinical impact, especially when differentiation from cancer is an issue. This is analogous to autoimmune hepatitis where steroid treatment is justified when the entity is highly suspected, and the response to treatment is incorporated into the diagnostic scoring system[66]. If steroid therapy fails to show clinical improvement, imaging studies should be performed again to differentiate AIP from pancreatic cancer. There are opposes against including the response to the steroid into the diagnostic criteria of AIP. They argue that steroid is not usually prescribed in any other type of chronic pancreatitis and one has to strongly suspect AIP in the first place to ever consider steroid therapy. To observe the response to the oral steroid in patients suspected of AIP, however, may be a diagnostic trial as well as therapeutic trial. Actually, in one Japanese university hospital and Italian group, they use the response to the steroid as one diagnostic criterion of AIP[50,70].

There are also concerns of the possibility of cancer progression during a trial of steroid therapy in an operable patient[6]. Despite this risk, we believe that a trial with steroids can be used to guide diagnosis when used in a proper fashion. If a patient shows typical pancreatic images of AIP, a short course (about 2 wk) of steroid may differentiate AIP from pancreatic cancer due to the fact that pancreatic ductal images of malignancy do not change[32,50]. And if the results are equivocal or do not favor AIP, the diagnosis of AIP should undergo reevaluation and the possibility of laparotomy should be considered. By including the response to the steroid into the diagnostic criteria, we can overcome the fact that there are patients who do not satisfy laboratory data and histologic findings, yet reveal typical images and an excellent response to the steroid.

Association of other postulated autoimmune diseases

Autoimmune diseases tend to cluster, and one patient may have more than one autoimmune conditions[43]. This is also the case in AIP which is frequently associated with

Sjögren’s syndrome, retroperitoneal fibrosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, and inflammatory bowel disease[71]. This association may be explained by the fact that carbonic anhydrase II and lactoferrin are present in the salivary gland and biliary duct as well as the pancreas. An autoimmune response against these common antigens may result in “autoimmune exocrinopathy” which describes an autoimmune disease that involves multiple exocrine organs[72]. On the basis of the absence or presence of a systemic autoimmune diseases, Okazaki et al[14] divided AIP into 2 major groups: Primary or secondary forms of the disease. In contrast to the Japanese criteria, Italian group has included the association of other postulated autoimmune disease into their diagnostic criteria of AIP (Table 4)[50].

Table 4.

Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis by Italian group

| Diagnostic criteria |

| 1 Histology and cytology |

| 2 The association with other postulated autoimmune disease |

| 3 Response to the steroid therapy |

The prevalence of other postulated autoimmune diseases, however, varies among papers with some reporting rates that exceed 50%[50]. Comorbidities are manifested at various time points on the natural course of AIP; some manifest before AIP and some simultaneously and others after remission[32]. Thus, primary form of AIP may need to be changed to secondary form in cases where other autoimmune diseases are not recognized at diagnosis of AIP but develop later. For patients with AIP, the presence of an associated autoimmune disease may help the diagnosis, but if not present at the onset of the disease, we must carefully search for it.

In addition, pancreatitis in patients suffering from other autoimmune diseases does not always indicate that the cause of pancreatitis is autoimmunity. For example, when pancreatitis occurs in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, pancreatitis can be related to various causes, such as vasculitis or medications[73]. This also adds confusion in reporting AIP in patients with underlying autoimmune conditions. In these cases, the remarkable response to steroids can help identify autoimmunity as the cause of pancreatitis[74].

REVISED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR AIP: OUR PROPOSAL

The Japan Pancreas Society proposed diagnostic criteria in 2002 (Table 1). In our experience, a considerable number of cases of AIP is diagnosed confidently when these criteria are applied. Clinicians, however, reported cases that benefited with steroid therapy that did not satisfy the criteria[11]. In our study, 9 of 28 (32%) patients with AIP did not fulfill Japanese criteria, yet responded to the steroid (Table 3). In other words, clinicians may miss a substantial portion of patients suffering from AIP when the diagnosis is confined to those who satisfy the criteria proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society.

On the basis of a single institute experience of 28 patients, we introduce the following system for the diagnosis of AIP (Table 5). We have designed a system where patients are stratified by evidence strength for AIP into “definite”, “probable” and “possible”. We respect the diagnostic criteria proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society and believe that it contains the strongest findings that support the diagnosis of AIP. Some of the original descriptions create confusion and the diagnostic criteria are not completely satisfactory. Descriptions have been, therefore, rephrased and the diagnostic criteria have been expanded to include more patients who can benefit from this diagnosis. While “definite” AIP is almost same as the original Japanese criteria, those who only reveal typical pancreatic images of AIP are diagnosed as “possible” AIP. This is because the combination of pancreatic imaging (CT and ERCP) seen in AIP is quite distinctive and rarely seen in any other disease entity. When other postulated autoimmune diseases are associated with typical pancreatic images of AIP, the suspicion index becomes higher and patients are designated as “probable” AIP. The diagnosis of AIP is confirmed by the unique response to steroid that can be observed by the dramatic resolution of pancreatic ductal narrowing, and then patients are reassigned to “definite”.

Table 5.

A proposal of revised diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis

| Diagnostic Criteria | |

| Criterion I. Pancreatic imaging (essential) | |

| (1) CT: Diffuse enlargement (swelling) of pancreas and (2) ERCP: Diffuse or segmental irregular narrowing of main pancreatic duct | |

| Criterion II. Laboratory findings | |

| (1) elevated levels of IgG and/or IgG4 or (2) detected autoantibodies | |

| Criterion III. Histopathologic findings | |

| Fibrosis and lymphoplasmocytic infiltration | |

| Criterion IV. Association of other postulated autoimmune disease | |

| Definite | |

| I+II+III+IV or I+II +III or I+II or I+III | |

| Probable | Rediagnosed as “definite” if “response to the steroid” is present |

| I+IV | |

| Possible | |

| I only | |

We believe that patients who present with typical pancreatic images of AIP deserve a short course of steroids before undergoing surgical resection, despite the lack of any serologic markers of autoimmunity or pathognomonic histopathologic findings. The results of serologic markers and histologic examination in patients with AIP may be closely related to the disease activity (active vs inactive) or the stage (early vs late) of the disease. In our proposal, therefore, a diagnostic trial of steroid can be initiated even though serologic markers or pathologic findings do not fulfill the Japanese criteria or are not available, providing that pancreatic images are typical to AIP.

The Japan Pancreas Society emphasizes imaging (CT and ERCP) criterion and serologic abnormalities as important and relatively specific markers for this entity, while they do not use “the response to the steroid” and “association of other postulated autoimmune diseases” as diagnostic criteria (Table 1). However, Italian experience does not believe imaging findings and serologic abnormality are specific (Table 4). In our revised diagnostic criteria (Table 5), pancreatic imaging (CT and ERCP) is also essential and the findings are almost same as Japanese criteria. Instead, we abolished the condition “more than 1/3 of the entire length of main pancreatic duct” and added “segmental” irregular narrowing. In the laboratory criterion, we newly inserted elevated serum IgG4 level. Consequently, more patients may benefit from oral steroid therapy and can avoid unnecessary major operation. In addition to pancreatic imaging, we included the response to the steroid and association with other postulated autoimmune diseases in the diagnostic criteria, in order to reduce cases that might be occluded by the Japanese criteria. It is already well known that the general features of autoimmune diseases include detected serum autoantibodies or elevated IgG, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis at the lesional site, response to the steroid and association with other autoimmune diseases (Table 6)[68]. Among the general features of autoimmune diseases, one feature does not have more evidence of strength to be superior to the others in the diagnosis of AIP. We, therefore, used all aforementioned features of autoimmune disease for the diagnosis of AIP.

Table 6.

General features of autoimmune diseases

| General features of autoimmune diseases |

| 1 Elevated levels of serum gammaglobulin and/or IgG, or detected autoantibody |

| 2 Lymphoplasma cell infiltration and fibrosis at lesional site |

| 3 Association with other autoimmune diseases |

| 4 Response to the steroid |

CONCLUSION

Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis (AIP) is a relatively new disease entity to many physicians, yet because of the clinical impact, they must vigilantly look for it. This review discusses several potential limitations of current diagnostic criteria for this increasingly recognized condition. The manuscript is organized to emphasize the need for convening a consensus to develop improved diagnostic criteria. These efforts will refine the diagnosis of AIP, which will lead to less inter-observer variation and provide a strong base for the research of this treatable condition.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Bi L

References

- 1.Yoshida K, Toki F, Takeuchi T, Watanabe S, Shiratori K, Hayashi N. Chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune abnormality. Proposal of the concept of autoimmune pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1561–1568. doi: 10.1007/BF02285209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okazaki K, Chiba T. Autoimmune related pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;51:1–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Etemad B, Whitcomb DC. Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:682–707. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erkelens GW, Vleggaar FP, Lesterhuis W, van Buuren HR, van der Werf SD. Sclerosing pancreato-cholangitis responsive to steroid therapy. Lancet. 1999;354:43–44. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)00603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishino T, Toki F, Shiratori K, Oi I, Oyama H. Efficacy and issues related to prednisolone therapy of autoimmune pancreatitis(abstr) Pancreas. 2005;31:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton R. Autoimmune pancreatitis--also a Western disease. Gut. 2005;54:581–583. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.058438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KP, Kim MH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Autoimmune pancreatitis: it may be a worldwide entity. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1214. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okazaki K. Autoimmune pancreatitis is increasing in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1557–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Members of the Criteria Committee for Autoimmune Pancreatitis of the Japan Pancreas Society. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis by the Japan Pancreas Society. J Jpn Pan Soc. 2002;17:585–587. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aparisi L, Farre A, Gomez-Cambronero L, Martinez J, De Las Heras G, Corts J, Navarro S, Mora J, Lopez-Hoyos M, Sabater L, et al. Antibodies to carbonic anhydrase and IgG4 levels in idiopathic chronic pancreatitis: relevance for diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54:703–709. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okazaki K, Uchida K, Asada M, Chiba T. Immunologic background in autoimmune pancreatitis. J Jpn Pan Soc. 2002;17:628–635. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abe N, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis. J Jpn Pan Soc. 2002;17:636–640. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim KP, Kim MH, Song MH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1605–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okazaki K, Uchida K, Chiba T. Recent concept of autoimmune-related pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s005350170094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kamata N. Clinical difficulties in the differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2694–2699. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Farrell J, Maher MM, Saini S, Mueller PR, Lauwers GY, Fernandez CD, Warshaw AL, Simeone JF. Autoimmune pancreatitis: imaging features. Radiology. 2004;233:345–352. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Procacci C, Carbognin G, Biasiutti C, Frulloni L, Bicego E, Spoto E, el-Khaldi M, Bassi C, Pagnotta N, Talamini G, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis: possibilities of CT characterization. Pancreatology. 2001;1:246–253. doi: 10.1159/000055819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balthazar EJ. Acute pancreatitis: assessment of severity with clinical and CT evaluation. Radiology. 2002;223:603–613. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2233010680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irie H, Honda H, Baba S, Kuroiwa T, Yoshimitsu K, Tajima T, Jimi M, Sumii T, Masuda K. Autoimmune pancreatitis: CT and MR characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1323–1327. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.5.9574610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawaguchi K, Koike M, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Tabata I, Fujita N. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis: a variant of primary sclerosing cholangitis extensively involving pancreas. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:387–395. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heuck A, Maubach PA, Reiser M, Feuerbach S, Allgayer B, Lukas P, Kahn T. Age-related morphology of the normal pancreas on computed tomography. Gastrointest Radiol. 1987;12:18–22. doi: 10.1007/BF01885094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muranaka T. Morphologic changes in the body of the pancreas secondary to a mass in the pancreatic head. Analysis by CT. Acta Radiol. 1990;31:483–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishino T, Toki F, Oyama H, Oi I, Kobayashi M, Takasaki K, Shiratori K. Biliary tract involvement in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Axon AT. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in chronic pancreatitis. Cambridge classification. Radiol Clin North Am. 1989;27:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer MV, Gyr K, Sarles H. [2d symposium on the classification of pancreatitis. Marseilles, 28-30 March 1984] Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1985;48:579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue K, Ohuchida J, Ohtsuka T, Nabae T, Yokohata K, Ogawa Y, Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M. Severe localized stenosis and marked dilatation of the main pancreatic duct are indicators of pancreatic cancer instead of chronic pancreatitis on endoscopic retrograde balloon pancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:510–515. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)01962-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shemesh E, Czerniak A, Nass S, Klein E. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in differentiating pancreatic cancer coexisting with chronic pancreatitis. Cancer. 1990;65:893–896. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900215)65:4<893::aid-cncr2820650412>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HJ, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Kim YT, Lee DK, Song SY, Roe IH, Kim JH, Chung JB, Kim CD, Shim CS, Yoon YB, Yang US, Kang JK, Min YI. Normal structure, variations, and anomalies of the pancreaticobiliary ducts of Koreans: a nationwide cooperative prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:889–896. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.124635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajan E, Clain JE, Levy MJ, Norton ID, Wang KK, Wiersema MJ, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Nelson BJ, Jondal ML, Kendall RK, et al. Age-related changes in the pancreas identified by EUS: a prospective evaluation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02758-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toki F, Nishino T, Oyama H, Karasawa L, Shiratori K, Oi I. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: Imaging criteria. J Jpn Pan Soc. 2002;17:598–606. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wakabayashi T, Kawaura Y, Satomura Y, Fujii T, Motoo Y, Okai T, Sawabu N. Clinical study of chronic pancreatitis with focal irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct and mass formation: comparison with chronic pancreatitis showing diffuse irregular narrowing of the main pancreatic duct. Pancreas. 2002;25:283–289. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horiuchi A, Kawa S, Hamano H, Hayama M, Ota H, Kiyosawa K. ERCP features in 27 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:494–499. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koga Y, Yamaguchi K, Sugitani A, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Autoimmune pancreatitis starting as a localized form. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:133–137. doi: 10.1007/s005350200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klöppel G, Lüttges J, Löhr M, Zamboni G, Longnecker D. Autoimmune pancreatitis: pathological, clinical, and immunological features. Pancreas. 2003;27:14–19. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takase M, Suda K. Histopathology of so-called autoimmune pancreatitis. Kan Tan Sui. 2001;43:233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lehman GA. Role of ERCP and other endoscopic modalities in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S237–S240. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Remer EM, Baker ME. Imaging of chronic pancreatitis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1229–142, v. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(02)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim KP, Kim M, Lee YJ, Song MH, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Min YI, Song DE, et al. [Clinical characteristics of 17 cases of autoimmune chronic pancreatitis] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2004;43:112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pezzilli R, Casadei R, Calculli L, Santini D. Autoimmune pancreatitis. A case mimicking carcinoma. JOP. 2004;5:527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamisawa T, Okamoto T. Pitfalls of MRCP in the diagnosis of pancreaticobiliary maljunction. JOP. 2004;5:488–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okazaki K. Autoimmune pancreatitis: etiology, pathogenesis, clinical findings and treatment. The Japanese experience. JOP. 2005;6:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose NR. Autoimmune diseases: tracing the shared threads. Hosp Pract (1995) 1997;32:147–154. doi: 10.1080/21548331.1997.11443469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uchida K, Okazaki K, Asada M, Yazumi S, Ohana M, Chiba T, Inoue T. Case of chronic pancreatitis involving an autoimmune mechanism that extended to retroperitoneal fibrosis. Pancreas. 2003;26:92–94. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horiuchi A, Kawa S, Akamatsu T, Aoki Y, Mukawa K, Furuya N, Ochi Y, Kiyosawa K. Characteristic pancreatic duct appearance in autoimmune chronic pancreatitis: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:260–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Egawa N, Irie T, Tu Y, Kamisawa T. A case of autoimmune pancreatitis with initially negative autoantibodies turning positive during the clinical course. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1705–1708. doi: 10.1023/a:1025426508414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okazaki K, Uchida K, Ohana M, Nakase H, Uose S, Inai M, Matsushima Y, Katamura K, Ohmori K, Chiba T. Autoimmune-related pancreatitis is associated with autoantibodies and a Th1/Th2-type cellular immune response. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:573–581. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahel J, Barthet M, Gasmi M. Autoimmune pancreatitis: increasing evidence for a clinical entity with various patterns. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1265–1268. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frulloni L, Bovo P, Brunelli S, Vaona B, Di Francesco V, Nishimori I, Cavallini G. Elevated serum levels of antibodies to carbonic anhydrase I and II in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2000;20:382–388. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearson RK, Longnecker DS, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Okazaki K, Frulloni L, Cavallini G. Controversies in clinical pancreatology: autoimmune pancreatitis: does it exist. Pancreas. 2003;27:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishimori I, Miyaji E, Morimoto K, Nagao K, Kamada M, Onishi S. Serum antibodies to carbonic anhydrase IV in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54:274–281. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.049064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, Unno H, Furuya N, Akamatsu T, Fukushima M, Nikaido T, Nakayama K, Usuda N, et al. High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:732–738. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujii T, Yoshida A, Yanagawa N. Significance of IgG4 measurement in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;31:2. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, Ando T, Aoki S, Kobayashi S, Okamoto T, Nomura T, Joh T, Itoh M. Clinical differences between primary sclerosing cholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawa S, Ota M, Yoshizawa K, Horiuchi A, Hamano H, Ochi Y, Nakayama K, Tokutake Y, Katsuyama Y, Saito S, et al. HLA DRB10405-DQB10401 haplotype is associated with autoimmune pancreatitis in the Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1264–1269. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishimori I, Suda K, Oi I, Ogawa M. Research on the clinical state of autoimmune pancreatitis. J Jpn Pan Soc. 2002;17:619–627. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song MH, Kim MH, Jang SJ, Lee SK, Lee SS, Han J, Seo DW, Min YI, Song DE, Yu E. Comparison of histology and extracellular matrix between autoimmune and alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:272–278. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000153211.64268.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suda K, Takase M, Fukumura Y, Ogura K, Ueda A, Matsuda T, Suzuki F. Histopathologic characteristics of autoimmune pancreatitis based on comparison with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:355–358. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000160283.41580.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suda K, Shiotsu H, Nakamura T, Akai J, Nakamura T. Pancreatic fibrosis in patients with chronic alcohol abuse: correlation with alcoholic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:2060–2062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakanuma Y, Harada K, Katayanagi K, Tsuneyama K, Sasaki M. Definition and pathology of primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s005340050127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klöppel G, Lüttges J, Sipos B, Capelli P, Zamboni G. Autoimmune pancreatitis: pathological findings. JOP. 2005;6:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wray CJ, Ahmad SA, Matthews JB, Lowy AM. Surgery for pancreatic cancer: recent controversies and current practice. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1626–1641. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levy MJ, Reddy RP, Wiersema MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Harewood GC, Pearson RK, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Yusuf TE, et al. EUS-guided trucut biopsy in establishing autoimmune pancreatitis as the cause of obstructive jaundice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:467–472. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burak KW, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Is there a role for liver biopsy in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1155–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Czaja AJ, Freese DK. Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479–497. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taniguchi T, Tanio H, Seko S, Nishida O, Inoue F, Okamoto M, Ishigami S, Kobayashi H. Autoimmune pancreatitis detected as a mass in the head of the pancreas without hypergammaglobulinemia, which relapsed after surgery: case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1465–1471. doi: 10.1023/a:1024743218697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mackay IR. Autoimmune disease. Med J Aust. 1969;1:696–699. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1969.tb105459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Song MH, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Lee SS, Han J, Kim KP, Min YI, Song DE, Yu E, et al. Regression of pancreatic fibrosis after steroid therapy in patients with autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2005;30:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawa S, Hamano H. Assessment of serological markers for the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. J Jpn Pan Soc. 2003;17:607–610. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H. Autoimmune pancreatitis is a systemic autoimmune disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2811–2812. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dooreck BS, Katz P, Barkin JS. Autoimmune pancreatitis in the spectrum of autoimmune exocrinopathy associated with sialoadenitis and anosmia. Pancreas. 2004;28:105–107. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Penalva JC, Martínez J, Pascual E, Palanca VM, Lluis F, Peiró F, Pérez H, Pérez-Mateo M. Chronic pancreatitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in a young girl. Pancreas. 2003;27:275–277. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kojima E, Kimura K, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Itoh K, Fujita N. Autoimmune pancreatitis and multiple bile duct strictures treated effectively with steroid. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:603–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]