Abstract

Hydatid disease is caused by the larval stage of the genus Echinococcus. Live hydatid cysts can rupture into physiologic channels, free body cavities or adjacent organs. Although hydatid disease can develop anywhere in the human body, the liver is the most frequently involved organ, followed by the lungs. Cysts of the spleen are unusual. There are only five case reports of spontaneous cutaneous fistulization of liver hydatid cysts in the literature. But there isn’t any report about cutaneous fistula caused by splenic hydatid cyst. We report a first case of spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected splenic hydatid cyst.

A 43-year-old man was admitted to our Emergency Service with abdominal pain and fluid drainage from the abdominal wall. He has been suffering from a reddish swelling on the abdominal wall skin for four months. After a white membrane had been protruded out from his abdominal wall, he was admitted to our Emergency Service. On physical examination, a white membrane was seen to protrude out from the 2 cm x 1 cm skin defect on the left superolateral site of the umblicus. Large, complex, cystic and solid mass of 9.5 cm-diameter was located in the spleen on ultrasonographic examination. At operation, partial cystectomy and drainage was performed. After the operation, he was given a dosage of 10 mg/kg per day of albendazole, divided into three doses. He was discharged on the postoperative 10th d. It should be kept in mind that splenic hydatid cysts can cause such a rare complication.

Keywords: Hydatid cyst, Cutaneous fistula, Spleen

INTRODUCTION

Hydatid disease is caused by the larval stage of the genus Echinococcus. Echinococcosis has a worldwide distribution because of increasing migration and a growing incidence of world travel. It is endemic in many Mediterranean countries, the middle and Far East, South America, Australia, New Zealand and East Africa[1].

The most common form, cystic hydatid disease, is caused by Echinococcus granulosus, whereas the alveolar type is caused by E. multiocularis. Approximately 70 percent of hydatid cysts are located in the liver and there are multiple cysts in one-quarter to one-third of these cases[2].

Live hydatid cysts can rupture into physiologic channels, free body cavities or adjacent organs[1]. There are only five case reports of spontaneous cutaneous fistulization of liver hydatid cysts in the literature[3-7]. But there isn’t any report about cutaneous fistula caused by splenic hydatid cyst.

We report a first case of spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected splenic hydatid cyst.

CASE REPORT

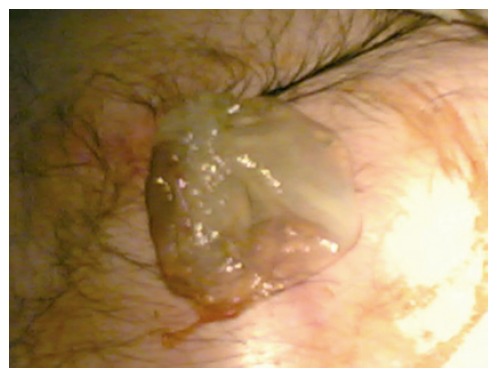

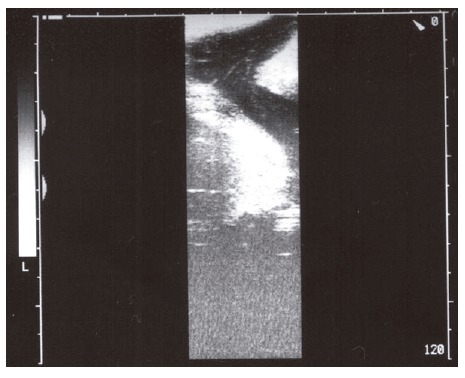

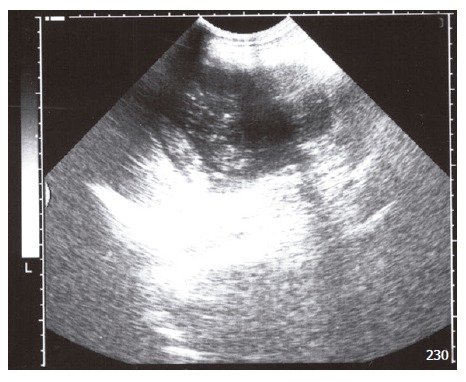

A 43-year-old man was admitted to our Emergency Service with abdominal pain and fluid drainage from the abdominal wall. He has been suffering from a reddish swelling on the abdominal wall skin for four months. He stated that some hemopurulent drainage was occured from this swelling two months before. He didn’t go to any doctor during this period. The drainage was stopped spontaneously in two days. He was no other complaints after that. Two days before, hemopurulent drainage and pain were started again. After a white membrane had been protruded out from his abdominal wall, he was admitted to our Emergency Service. On physical examination, there was a 2 cm x 1 cm skin defect on the left superolateral site of the umblicus (Figure 1). This defect was at a distance of 3 cm to the umblicus. A white membrane was protruded out from this defect. This membrane looked like the germinative membrane of hydatid cyst. Laboratory findings were as follows; hemoglobin: 11.7 g/dL, white blood count: 18 800/mm3, platelet: 632 000/mm3, alkaline phosphatase: 270 U/L, gamma glutamyl trans-peptidase: 51 U/L. Other laboratory findings were normal. Ultrasonography (USG) was the modality of choice for this patient. Large, complex, cystic and solid mass of 9.5 cm-diameter was located in the spleen. Mass showed a complex internal character with multiple floating membranes, echogenic foci due to hydatid sand and heterogenous-echogenic matrix which are characteristic imaging findings for hydatid disease. Mass passed through the anterior abdominal wall from 5 cm-diameter peritoneal defect. Fistula tract on the anterior abdominal wall and cutaneous orifice were also seen (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Germinative membrane protruded out from the 2 cm x 1 cm skin defect on the left superolateral site of the umblicus.

Figure 2.

Fistula tract on the anterior abdominal wall.

Figure 3.

Large, complex, cystic and solid mass located in the spleen.

At operation, 300 mL purulent material was drained from the subcutaneous tissue after skin incision. The germinative membrane in the fascial defect was taken in the abdomen. Approximately 1.5 liters of infected hydatid cyst material was aspirated from the cyst cavity. On exploration, the cyst was found to be localized in the splenic parenchyma. There were multiple adhesions between the cyst and spleen, liver, stomach and abdominal wall. There was a 5 cm-diameter fascial defect on the lateral side of the left rectus muscle. This was the defect from where the germinative membrane was protruded out of the abdomen. Adhesions were dissected and partial cystectomy was performed. There were splenic fragments in the cyst cavity. The cyst cavity was cleaned and 10% povidone iodine was applied to the cyst wall. Two drains were left in the abdomen; one in the cyst cavity and the other in the left paracolic region. The perforated skin area was debridated but not sutured. After the operation, he was given a dosage of 10 mg/kg/d of albendazole, divided into three doses. He was discharged on the postoperative 10th d. He came to first control three mo after the operation. USG and computerized tomography (CT) examinations together with serologic tests were normal.

DISCUSSION

We present the first case of spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected splenic hydatid disease. The clinical features of hydatid disease depend on the site, size, stage of development, whether the cyst is dead or alive and whether there is a complication or not[1]. Patients with simple or uncomplicated multivesicular cysts are usually asymptomatic. The clinical symptoms are related to pressure on adjacent organs or the presence of complications. Abdominal pain and tenderness are the most common complaints[2].

The hydatid disease can remain symptom-free for years or cause serious complications resulting in death. The main complications are rupture into the peritoneal cavity, infection, compression of the biliary tree, intrabiliary rupture, anaphylaxis, and secondary hydatosis[8].

Intrabiliary rupture represents the most common complication and occurs in 5 to 10 % of cases[2]. T-tube drainage, choledochoduodenostomy and transduodenal sphincteroplasty are effective procedures in the management of intrabiliary ruptured hydatid disease[9-11]. Suppuration, the second most common complication, is caused by bacteria from the biliary tract. Intraperitoneal rupture results in the showering of hydatid fluid, brood capsules, and scolices into the peritoneum; leading to systemic anaphylactic reactions or the development of new hydatid cyst[2,12,13].

Spontaneous cutaneous fistulization is a very rare complication of liver hydatid cysts. There are only five case reports in the literature[3-7]. Two of them are cysto-hepato-bronchial fistula[3,5]. In these cases, liver hydatid cysts were fistulized simultaneously and spontaneously to the skin and in the bronchia. The other cases were cutaneous fistula of liver hydatid cysts[4,6,7].

A viable hydatid cyst is a space-occupying lesion with a tendency to grow. In confined areas, such as the central nervous system, small cysts cause serious symptoms. In less restricted areas the symptoms depend on the site and size of the cyst. Symptoms may result from direct pressure or distortion of neighboring structures or viscera. The cyst grows in the direction of the least resistance. Another consequence of cyst enlargement is that it can rupture. Live hydatid cysts can rupture into physiologic channels, free body cavites or adjacent organs. The other factor responsible for fistulization of hydatid disease is inflammation. Infection and continued expansion of the cyst causes pressure erosion and adhesion to the adjacent structures. In time, with increasing intracystic pressure, the cyst ruptures. Inflammation leads to necrosis and causes fistulization[1]. In our case, inflammation is probably the main factor of cutaneous fistulization.

Although hydatid disease can develop anywhere in the human body, the liver is the most frequently involved organ (52%-77%), followed by the lungs (10%-40%)[8]. Cysts of the spleen are unusual. Parasitic cysts are usually due to echinococcal involvement, while non-parasitic cysts can be categorized as dermoid, epidermoid, epithelial, and pseudocysts[2]. The spleen is infrequently involved in hydatid disease. Ozdogan et al[14] reported that the spleen was involved in 2.5% of all abdominal hydatidosis cases. They suggested that although splenectomy was the conventional treatment, partial cystectomy and omentopexy could be another choice for the treatment of splenic hydatosis.

Splenic abscess is an uncommon cause of splenic abdominal sepsis. Splenectomy is the operation of choice, but some patients have been treated with splenectomy and drainage when there were gross adhesions or the condition of the patient did not permit splenectomy[2]. In our case, we performed partial cystectomy and drainage. Because of dense adhesions and abscess formation, we didn’t perform splenectomy. There was no recurrence in abdominal cavity, including spleen, at USG and CT imaging performed 3 mo after the operation. If recurrence occur, we will perform total splenectomy as a second operation.

Benzimidazole carbamates (mebendazole and albendazole) are antihelmintic drugs that kill the parasite by impairing its glucose uptake. Albendazole is the drug of choice because of its better absorption and better clinical results in comparison with mebendazole. Continuous daily treatment for a 3-mo period has better results[13]. We proposed our patient a dosage of 10 mg/kg per day albendazole for 3 mo and a 3-mo period controls.

We reported a first case of spontaneous cutaneous fistula of infected splenic hydatid cyst. It should be kept in mind that splenic hydatid cysts can cause such a rare complication.

Footnotes

S- Editor Wang J E- Editor Cao L

References

- 1.Milicevic MN. Hydatid disease. In: Blumgart LH, Fong Y, eds , editors. Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract. London: W.B. Saunders Company Ltd; 2000. pp. 1167–1204. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz SI. Principles of Surgery. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 1999. pp. 1395–1435. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kehila M, Allègue M, Abdesslem M, Letaief R, Saïd R, Ben Hadj Hamida R, Khalfallah A, Jerbi A, Jeddi M, Gharbi S. [Spontaneous cutaneous-cystic-hepatic-bronchial fistula due to an hydatid cyst] Tunis Med. 1987;65:267–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golematis BC, Karkanias GG, Sakorafas GH, Panoussopoulos D. [Cutaneous fistula of hydatid cyst of the liver] J Chir (Paris) 1991;128:439–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harandou M, el Idrissi F, Alaziz S, Cherkaoui M, Halhal A. [Spontaneous cutaneous cysto-hepato-bronchial fistula caused by a hydatid cyst. Apropos of a case] J Chir (Paris) 1997;134:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grigy-Guillaumot C, Yzet T, Flamant M, Bartoli E, Lagarde V, Brazier F, Joly JP, Dupas JL. [Cutaneous fistulization of a liver hydatid cyst] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:819–820. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(04)95139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bastid C, Pirro N, Sahel J. [Cutaneous fistulation of a liver hydatid cyst] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:748–749. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(05)88218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayek I, Tirnaksiz MB, Dogan R. Cystic hydatid disease: current trends in diagnosis and management. Surg Today. 2004;34:987–996. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köksal N, Müftüoglu T, Günerhan Y, Uzun MA, Kurt R. Management of intrabiliary ruptured hydatid disease of the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1094–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paksoy M, Karahasanoglu T, Carkman S, Giray S, Senturk H, Ozcelik F, Erguney S. Rupture of the hydatid disease of the liver into the biliary tracts. Dig Surg. 1998;15:25–29. doi: 10.1159/000018582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elbir O, Gundogdu H, Caglikulekci M, Kayaalp C, Atalay F, Savkilioglu M, Seven C. Surgical treatment of intrabiliary rupture of hydatid cysts of liver: comparison of choledochoduodenostomy with T-tube drainage. Dig Surg. 2001;18:289–293. doi: 10.1159/000050154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sözüer EM, Ok E, Arslan M. The perforation problem in hydatid disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:575–577. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schipper HG, Kager PA. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic echinococcosis: an overview. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2004:50–55. doi: 10.1080/00855920410011004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozdogan M, Baykal A, Keskek M, Yorgancy K, Hamaloglu E, Sayek I. Hydatid cyst of the spleen: treatment options. Int Surg. 2001;86:122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]