Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a major cause of death among patients with cirrhosis. A standardized approach of multimodality therapy with intent-to-treat by transplantation for all patients with hepatocellular carcinoma was instituted at our transplant center in 1997. Data were prospectively collected to evaluate the impact of multimodality therapy on post-transplant patient survival, tumor recurrence and patient survival without transplantation.

Methods

All patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were eligible for multimodality therapy. Multimodality therapy consisted of hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, transarterial chemoinfusion, yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization and sorafenib.

Results

715 patients underwent multimodality therapy. 231 patients were included in the intent-to-treat with transplantation arm and 484 patients were treated with multimodality therapy or palliative therapy due to contraindications for transplantation. A 60.2% transplantation rate was achieved in the intent-to-treat with transplantation arm. Post-transplant survivals at 1- and 5-years were 97.1% and 72.5% respectively. Tumor recurrence rates at 1-, 3- and 5-years were 2.4%, 6.2% and 11.6% respectively. Patients with contraindications to transplant had increased 1- and 5-year survival from diagnosis with multimodality therapy compared to those not treated (73.1% and 46.5% vs. 15.5% and 4.4%, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Using multimodality therapy prior to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma achieved low recurrence rates and post-transplant survival equivalent to patients with primary liver disease without hepatocellular carcinoma. Multimodality therapy may help identify patients with less active tumor biology and result in improved disease-free survival and organ utilization.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation, transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, liver resection, hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary malignant tumor of the liver and a major cause of death among patients with cirrhosis (1). Management of HCC is complicated by the challenge of treating late stage cancer in the setting of advanced liver disease. Over the past 20 years, the use of a multimodality therapy approach for HCC has improved overall 5-year survival from 7% to around 50%. Heralded by the Barcelona Clinic for Liver Cancer, current treatment algorithms incorporate a diverse range of therapies for different stages of liver cancer and disease (2). In 1996, Mazzafero et al. demonstrated a 72% 4-year survival for carefully selected patients with HCC and thereby established the Milan criteria for transplantation in HCC (3). Prior to this landmark study, no other intervention provided this robust of a survival benefit.

Although liver transplantation offers the best outcomes for HCC, the critical organ shortage limits opportunities for transplantation. Allocation schema must consider the risk of HCC patients dropping off the waitlist due to tumor progression whilst not compromising the survival of patients with primary liver disease awaiting liver transplantation. Recent data suggest that current allocation exception points unfairly advantage patients with HCC, and this concern is magnified by the poorer long-term outcomes seen in HCC patients due to tumor recurrence (4). Therefore, in the setting of HCC it is imperative to identify patients on the waitlist with the best probability for a successful outcome, and protect their access to transplantation without adversely affecting the access of patients with primary liver disease without HCC.

Beginning in 1997, a standardized multimodality therapy with intent-to-treat with liver transplantation protocol was prospectively implemented at our center for all patients with HCC. The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of this multimodality therapy approach on HCC recurrence rate, patient survival from diagnosis and post-transplant patient survival. Post-transplant survival using this approach was compared to the post-transplant survival in similar cohorts of patients without HCC at our center.

RESULTS

From 1998 to June 2012, 783 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were evaluated, staged and treated at our center. 68 patients were excluded, leaving a study group of 715 verified HCC patients with sufficient follow-up to determine treatment outcomes.

Of the 715 patients included in this prospective study, 231 (32.3%) patients were included in the intent-to-treat with transplant group (ITT) and 484 (67.7%) patients were included in the contraindications for transplant group (CFT). 139 of the 231 (60.2%) patients in the ITT group were successfully transplanted (ITT/Tx). 92 patients in the ITT group were not transplanted due to progression of their disease (ITT/No Tx) (Table 1). Five patients in the ITT/No Tx group remain on the waiting list as of the timing of this report. Of the 484 patients in the CFT cohort, advanced HCC was the most common contraindication for transplant (64.0%), followed by severe comorbidities (14.3%), death during evaluation (11.0%), ongoing alcohol or illicit drug use (8.7%), and advanced age (5.6%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at diagnosis of HCC

| ITT/Tx (n=139) | ITT/No Tx (n=92) | CFT (n=484) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.9 ±6.1 | 57.1 ±10.1 | 59.5 ±9.7* | <0.0001 |

| Males | 124 (89.2%)* | 65 (70.7%) | 364 (75.2%) | 0.001 |

| African American | 19 (13.7%)* | 29 (31.5%) | 155 (32.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Stage at diagnosis: | ||||

| T1 | 36 (25.9%) | 15 (16.3%) | 31 (6.4%)* | <0.0001 |

| T2 | 89 (64.0%) | 46 (50%) | 150 (31.0%)* | <0.0001 |

| T3 | 14 (10.1%) | 31 (33.7%)* | 79 (16.3%) | <0.0001 |

| T4 | 0 | 0 | 224 (46.3%)* | <0.0001 |

| Mean functional score at diagnosis: | ||||

| Child-Turcotte Pugh (1998-2002) | 7.0 ± 1.4 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | 7.1 ± 2.2 | 0.399 |

| Unadjusted MELD (2002-2012) | 12.4 ± 4.8 | 10.6 ± 5.6 | 12.0 ± 10.7 | 0.380 |

| Karnofsky (2002-2012) | 96.9 ± 7.3 | 95.7 ± 6.7 | 89.3 ± 15.4* | <0.001 |

| Median AFP (ng/mL) | 16.4 (1.7-2244) | 9.8 (1.3-4272) | 43 (1-513491)* | 0.02 |

| Patients who received MMT | 121 (87.1%) | 89 (96.7%) | 375 (77.5%)* | <0.0001 |

| Mean number of treatments per patient | 2.16 ±1.14 | 2.29 ±1.32 | 2.0 ±1.3 | 0.46 |

| Total number of treatments: | ||||

| TACE | 99 | 67 | 374 | 0.30 |

| RFA | 57 | 42 | 163 | 0.99 |

| TACI | 4 | 24 | 118 | 0.19 |

| Resection | 2* | 18 | 24 | <0.0001 |

| Y-90 | 0 | 6 | 55* | <0.0001 |

| Sorafenib | 0 | 6 | 39* | <0.0001 |

| Patients downstaged to T0 | 44 (31.7%) | 34 (37.0%) | 23 (4.8%)* | <0.0001 |

indicates the value is significantly different from the others at p<0.05 ITT/Tx: Intention-to-treat with transplant and transplanted ITT/No Tx: Intention-to-treat with transplant and not transplanted CFT: Contraindicated for transplant

Median wait times for transplantation after listing was 85 days (interquartile range: 45-189 days). There were 7 recipients of living-donor livers and their median wait time was 87 days (interquartile range: 48-118 days). In no instance was transplantation delayed by MMT, as reflected in the 10 patients that progressed straight to transplant before receiving MMT (Table 1).

The CFT cohort was older and presented with higher serum AFP levels, advanced T4 HCC and metastasis as compared to the ITT groups. Among the ITT groups, patients who were transplanted (ITT/Tx) were more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age and at an earlier stage. Functionally, the three groups had similar Childs-Turcotte-Pugh scores and unadjusted MELD scores. The CFT group had lower mean Karnofsky score as compared to the ITT groups (Table 1). Logistic modeling indicated that failure to proceed to transplant in the ITT group was independently associated with increasing number of treatments (odds ratio [OR]: 1.6; p=0.029), African-American race (OR: 2.9, p=0.004), and use of TACI (OR: 0.4; p=0.028).

There was no significant difference in the mean number of treatments between the groups. 87.1% of patients in the ITT/Tx group received MMT as compared to 96.7% of patients in the ITT/No Tx group. The 12.9% of patients that did not receive MMT in the ITT/Tx reflect 10 patients who received their transplants soon after evaluation before MMT could be initiated. Amongst the CFT group, 77.5% of patients received treatment (Table 1).

Of the patients that progressed to transplant, 25.9% presented at T1 stage, 64.0% at T2 stage and 10.1% at T3 stage. Hepatic resection was performed mostly in patients with T2 (30.2%) and T3 (53.5%) HCC. 66.7% of patients receiving sorafenib and 48.2% of patients receiving Y-90 were T4 stage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of patients treated with each modality by stage at HCC diagnosis

| Stage at diagnosis | Transplant (n=139) | RFA (n=195) | Resection (n=43) | TACE (n=324) | Y-90 (n=56) | Sorafenib (n=54) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 36 (25.9%) | 23 (11.8%) | 0 | 28 (8.6%) | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| T2 | 89 (64.0%) | 95 (48.7%) | 13 (30.2%) | 130 (40.1%) | 14 (25.0%) | 5 (9.3%) |

| T3 | 14 (10.1%) | 46 (23.6%) | 23 (53.5%) | 77 (23.8%) | 13 (23.2%) | 12 (22.2%) |

| T4 | 0 | 31 (15.9%) | 7 (16.3%) | 89 (27.5%) | 27 (48.2%) | 36 (66.7%) |

Outcomes of multimodality therapy and transplantation

The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival from time of diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was significantly higher in the ITT/Tx group (97.1%, 82.0% and 72.5%) as compared to the ITT/No Tx (71.3%. 43.1% and 35.0%) and CFT group (49.5%, 14.7% and 6.0%). The strongest predictor of improved patient survival from diagnosis on multivariate Cox proportional hazards modeling was receiving a liver transplant with adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 0.19 and 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.14-0.33. Significant predictors of decreased survival included older age (HR: 1.25; CI: 0.14-0.33), male gender (HR: 1.68; CI: 1.01-2.92) and presence of diabetes (HR: 1.54; CI: 1.02-2.30).

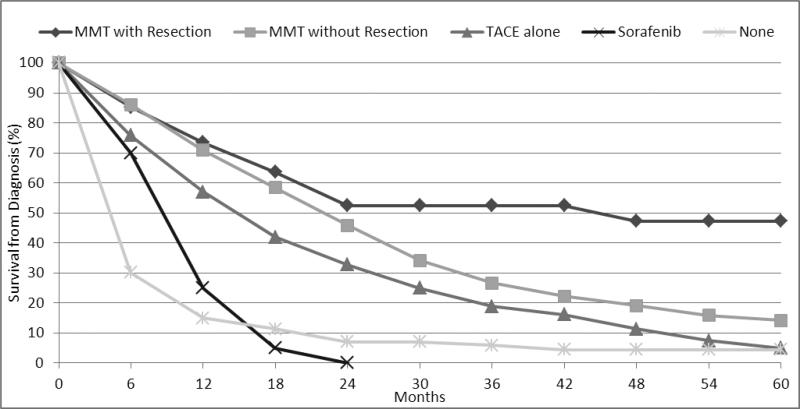

In the CFT group, the 1-, 3- and 5-years survival rates from time of diagnosis were worst for patients who did not receive any type of treatment (15.5%, 5.9% and 4.4%). MMT with resection offered the best survival from diagnosis with 1-, 3- and 5-years survival rates of 73.1%, 51.6% and 46.5% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival from diagnosis of HCC in patients contraindicated for liver transplantation

In the transplanted group, survival after liver transplantation at 1-, 3- and 5-years were 88.9%, 74.0% and 69.0%. This was similar to the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival in the non-HCC control subset of patients matched for age, race, and disease etiology, and the non-HCC control subset of hepatitis C cirrhosis patients with MELD score of 21 to 24. The HCC recurrence rates after liver transplantation at 1-, 3- and 5-years were 2.4%, 6.2% and 11.6% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of liver transplant outcomes for HCC

| ITT/Tx | Non-HCC Matched Controls | Non-HCC Hepatitis C and MELD 21-24 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=139 | n=214 | p-value* | n=65 | p-value* | |

| Donor Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 39.5 ± 17.3 | 39.0 ±16.1 | 0.782 | 41.2 ±17.3 | 0.514 |

| Males | 81 (58.3%) | 121 (56.5%) | 0.748 | 31 (47.7%) | 0.157 |

| African American | 27 (19.4%) | 47 (22.0%) | 0.567 | 22 (33.8%) | 0.025 |

| Donation after cardiac death | 6 (4.3%) | 8 (3.7%) | 0.786 | 1 (1.5%) | 0.310 |

| Cold ischemia time (minutes) | 442 ±198 | 378 ± 208 | 0.004 | 456 ±192 | 0.635 |

| Warm ischemia time (minutes) | 36.3 ± 8.9 | 34.8 ± 10.5 | 0.165 | 34.5 ±9.7 | 0.192 |

| Recipient Characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 55.4 ±6.1 | 52.6 ±7.0 | <0.0001 | 52.7 ±6.5 | 0.004 |

| Hepatitis C virus positivity | 107 (77.0%) | 158 (73.8%) | 0.179 | 100% | <0.0001 |

| Calculated MELD score before transplant | 12.9 ±6.1 | 19.2 ±6.6 | <0.0001 | 19.0 ±4.1 | <0.0001 |

| Listed MELD score at transplant | 23.5 ±3.6 | 22.2 ±6.2 | 0.026 | 23.0 ±1.5 | 0.283 |

| Transplant Outcomes | |||||

| 1-year patient survival | 88.9% | 87.8% | 0.159 | 89.1% | 0.996 |

| 3-year patient survival | 74.0% | 80.9% | 0.134 | 76.7% | 0.664 |

| 5-year patient survival | 69.0% | 74.2% | 0.698 | 66.4% | 0.678 |

| 1-year recurrence | 2.4% | - | - | ||

| 2-year recurrence | 6.2% | - | - | ||

| 3-year recurrence | 11.6% | - | - | ||

p-values are relative to the ITT/Tx group

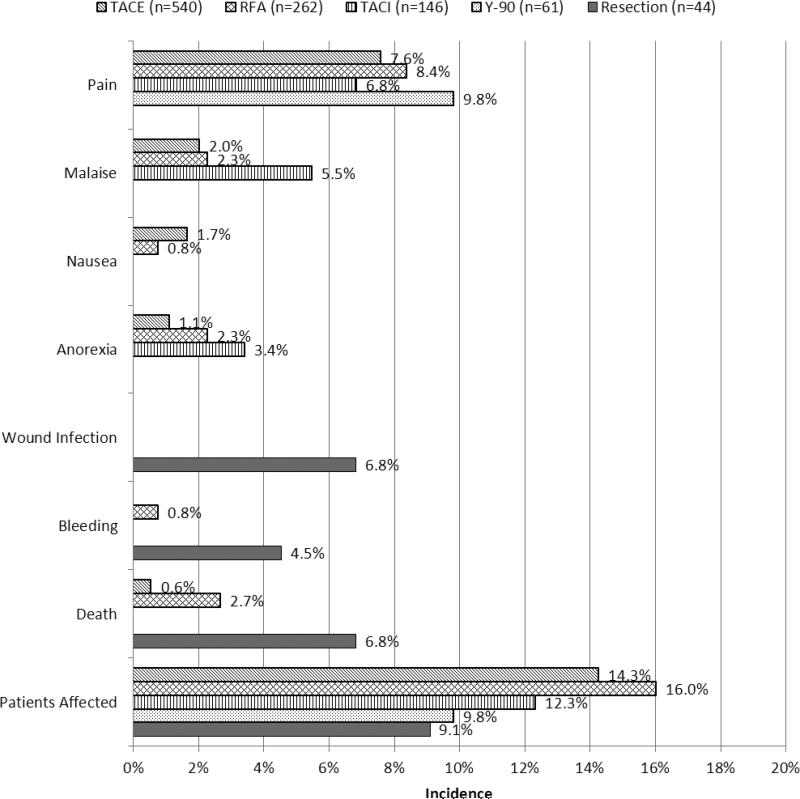

Overall, RFA was performed 262 times in 195 patients with a complication rate of 16.0%. TACE and TACI had complication rates of 14.3% and 12.3%. The most common complications noted in these procedures were pain, malaise and anorexia. Death was attributed to RFA in 7 cases (2.7%) and TACE in 3 cases (0.6%). Serious complications of bleeding and death were not noted with TACI. 44 hepatic resections were performed in 43 patients with 9.1% of patients experiencing at least one complication. There were three resection-related deaths (6.8%) and two instances of bleeding that required blood transfusion (Figure 2). Reoperation for bleeding was not required in either instance.

Figure 2.

Complications after multimodality therapy

DISCUSSION

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a challenging disease whose multimodality treatment approach has evolved to enhance the five-year post-transplant survival from 7% to greater than 50% (2,4). To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest prospectively-collected single-center series to date investigating the use of a standardized protocol for multimodality therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. The goal of this protocol was to maximize post-transplant outcomes (measured by high post-transplant survival and low cancer recurrence), while minimizing waitlist dropout of both HCC patients and non-cancer patients.

The current prioritization of liver transplantation for HCC disadvantages patients with primary liver disease and centers are realizing the impact of tumor recurrence on poor outcomes using a simple ‘list and transplant’ approach (4). Multimodality therapy (MMT) for HCC is attractive due to its potential for optimizing patients for transplantation through downstaging, and for delineating the biologic activity of the tumor (5,6). The University of California, San Francisco “ablate and wait” strategy uses TACE and RFA to downstage patients from T3 to fit the Milan criteria for transplantation (6). In their series of 61 patients, the dropout rate was 29.5% with 1- and 4-year survival rates amongst their intent-to-treat group of 87.5% and 69.3% respectively. They achieved 1- and 4-year post-transplant survival of 96.2% and 92.1%. In our center's practice, we used broader inclusion criteria for our intention-to-treat with transplant cohort. This cohort included all patients excepting those with advanced fixed comorbidities that served as contraindications for transplantation (advanced age, recent malignancy, and severe cardiopulmonary disease) and those with T4b cancers on presentation. As a result of the broader inclusionary criteria, we had a more substantial dropout rate (39.8%) and lower overall survival in our ITT group.

The 4-year post-transplant survival in our series (77.3%) compares favorably to series presented at other centers (3,7). Additionally, our post-transplant tumor recurrence rates at 1- and 4-years of 2.4% and 8.7% are superior to the other published rates of recurrence, which range from 8.3% to 20% at one to two years post-transplant (3,7-10). Furthermore, using this MMT protocol, we achieved 1- and 5-year post-transplant HCC survival that rivaled our non-HCC hepatitis C survival over the same time period (88.9% and 69.0% vs. 89.1% and 66.4% respectively). The equivalent 1- and 5-year survival suggests that this MMT approach selects HCC recipients with comparatively low biological tumor activity. Identifying and selecting such patients serves to maximize organ utilization and minimize recurrence.

Multimodality therapy was used as a treatment modality for loco-regional control of HCC in transplant candidates and for palliation in patients with advanced age, fixed comorbidities, or highly advanced cancers (T4b). In this study, among the patients with contraindications for transplant, MMT served to significantly prolong their survival from diagnosis. MMT, with or without resection, resulted in a 4-fold increase in 1-year survival and almost a 10-fold increase in 5-year survival as compared to receiving no treatment. While part of that benefit could be attributed to selection bias, the improved survival with multiple modalities of treatments versus TACE alone suggests a synergistic benefit. Serious complications related to MMT were limited to patients undergoing RFA or resection. The majority of the deaths after RFA resulted from sepsis and multi-organ failure, likely stemming from seeding of inflammatory necrosis-related mediators into the hepatic vasculature. Two of the three resection deaths in our study occurred in patients with more advanced cancers who succumbed to multi-organ failure. The incidence of complications associated with TACE and TACI did not differ from other reports in the literature (11-14).

The patients in each of the three cohorts of our study had similar Childs-Turcotte-Pugh and MELD scores at diagnosis. Despite this equivalency, the patients had variable response to MMT, progression to transplantation and survival. Tumor genetics vary in HCC and multiple genetic markers have been associated with tumor progression and recurrence (15-17). Recent reports further reveal that TACE and RFA affect molecular markers related to tumor aggressiveness and thus MMT may serve to uncover and, in certain cases, alter the underlying tumor biology (18,19). Clinically, patients presenting with higher tumor stage and AFP usually do not progress to transplant due to concerns that they harbor more advanced and biologically active tumors (20). However, in our series, presenting tumor stage and AFP were not significant variables in predicting progression to transplant. This may suggest that MMT, and specifically ablative therapy, does not only select patients with biologically less active tumors, but may modulate biologic activity of tumors in patients presenting with late stage advanced tumors. The ability of MMT to select for, or render tumors less biologically active, may be further reflected in the survival rates of the resected patients in our series. Unlike other centers where liver resection is limited to early stage lesions, 69.8% of the resected patients in our series presented with T3 or T4 stage tumors. Despite that, our 5-year post-resection survival rate of 46.5% compares favorably to the 30-50% 5-year survival rates published by other centers (21-23). This indicates that we achieved equivalent survival with resection in patients with more advanced disease. Future comparative genetic profiling of tumor characteristics in patients who received and did not receive MMT may shed additional light on the effect of MMT on biologic tumor activity.

Our series reaffirms that progression to liver transplantation is the best predictor of survival in patients with HCC (HR 5.3) (21,24,25). In our analysis of the variables predictive of progression to transplant, African American race emerged as a strong negative predictor of progression to transplant. This mirrors other findings of lower access to care, later stage at presentation and poorer overall transplant outcomes in African Americans and other ethnic and racial minorities (26,27). The role of specific barriers to transplantation like late stage at presentation, poor social support, continued alcohol use, and the inability to afford medications requires closer investigation in order to bridge the gap in timely access to care.

The strength of this large single-center study included the ability to carefully standardize the utilization of MMT across patients. However, due to the duration of this study, certain newer treatments could not be used in patients closer to the start of the study period. Additionally, certain differences in individual patient strategies were necessary to address unique clinical circumstances. Other limitations include the sample sizes for subgroup analyses and potential biases from retrospective definition of ITT, CFT, and control cohorts.

In conclusion, multimodality therapy may help select patients with less biologically active tumors and result in improved tumor-free survival after liver transplantation. This data argues against the ‘list and transplant’ approach for HCC, suggesting that more thorough investigation of tumor biology improves disease-free survival in patients with HCC and maximizes organ utilization. Our results add to the body of evidence that downstaged HCC patients should receive similar HCC exception MELD points as those patients that meet Milan criteria without MMT downstaging (28). Currently, most MELD-based allocation policies, including in the United States and United Kingdom, do not assign HCC exception MELD points to downstaged patients (29). This protocol uses disease progression after multimodality therapy as a surrogate for tumor activity and our data supports the drive to further identify alternative proteomic or genomic markers that may more accurately define tumor biology in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In December 1997, a prospective study was initiated to implement a multimodality treatment algorithm for screening, staging, and treating all patients who were referred to our center with HCC. The Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Hepatocellular carcinoma evaluation

As part of the HCC staging and transplant evaluation, patients underwent serial laboratory testing, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and radiologic testing. Tumors were staged based on ultrasonographic screening of the liver, followed by liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without intravenous contrast material, contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest and head, and total body bone scan (30,31). Questionable HCC diagnoses were confirmed by biopsy. All HCC patients were staged initially and serially with the American Liver Tumor Study Group modified tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging classification (32). Re-staging occurred at 3-month intervals and patients received life-long follow-up (33).

Prospective study design

After initial patient evaluation and prior to initiation of therapy, patients were stratified into five clinical groups that have been previously described (33-35). Briefly, group I consisted of patients with resectable disease, who were considered for transplantation if they had HCC recurrence after resection. Group II consisted of non-cirrhotic patients with tumors that were not amenable to resection due to unfavorable tumor size and anatomy. Group III consisted of cirrhotic unresectable patients with T1, T2 and T3 disease. Group III patients who fit the Milan criteria were listed for transplantation, while those outside Milan were surveilled at 3-month intervals for downstaging to within Milan criteria and subsequent listing for transplant. Group IV consisted of patients with sociobehavioral contraindications to transplantation (eg. continue alcohol or illicit drug use, inadequate social support). Group V consisted of patients with physiologic or tumor contraindications to transplantation (eg. severe comorbidities, T4B disease).

For purposes of statistical analysis, the prospective groups I, II and III were categorized as the intention to treat with transplant group, while groups IV and V were categorized as the contraindicated for transplant group, as described below. This realignment was performed to better delineate the role of MMT in patients with curative potential with transplantation and those with terminal disease or contraindications for transplantation.

Multimodality therapy

All patients referred to our transplant center with HCC were eligible for multimodality therapy. Multimodality therapy consisted of liver resection, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transarterial chemoinfusion (TACI), yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization (Y-90) and sorafenib (35,36). Specific treatment decisions were guided by a standardized institutional protocol and implemented by a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma team. The institutional protocol was formally reviewed by the multidisciplinary team each year. While resection, RFA, TACE and TACI were present at the start of the protocol in 1997, Sorafenib and Y-90 were introduced into the protocol in 2003 after safety analysis and approval from payor agencies.

In the MMT protocol, RFA was indicated for single or multiple distinct nodules less than or equal to 4cm, more than 1cm from major veins, and not displacing the liver capsule. Nodules over 4cm, less than 1cm from major veins, or displacing the liver capsule were treated with TACE, and rarely Y-90. These ablative treatments were repeated at 3-4 week intervals until MRI absence of arterial or portal inflow was achieved. Patients with multiple indistinct sub-centimeter lesions were treated with TACI if their total bilirubin was less than 4mg/dl and there was no evidence of portal vein thrombosis on MRI. All patients with tumors invading major veins or tumor thrombus were treated with Y-90. Resection was used in patients with Karnofsky scores greater than 70 and Childs A cirrhosis or hepatic fibrosis without evidence of portal hypertension. Sorafenib was given to patients with unresectable HCC that did not qualify for any of the above treatments (34,35).

MMT, and specifically TACE and RFA, was employed in all patients when feasible, including patients listed for transplantation and those scheduled for resection. This was performed as eradication of viable HCC could potentially prevent further growth while on the waitlist, and decrease the chances of propagation and spread occurring during surgical manipulation. In a HCC patient already listed, transplantation was never deferred or delayed for MMT if an organ match became available as long as last 3 month HCC surveillance MRI was within Milan stage.

Statistical groups

For analysis, the patients were retrospectively separated into two overall groups: an intention-to-treat with transplant (ITT) group and a contraindicated for transplant (CFT) group. The ITT group included patients with a Karnofsky functional score greater than or equal to 50, and was further divided into patients that progressed to transplant (ITT/Tx) and those that did not progress to transplant (ITT/No Tx). The contraindicated for transplant (CFT) group included patients over the age of 75 years, patients with fixed advanced cardiovascular disease, ongoing alcohol or illicit drug use, impaired cognition or neurologic disease, and patients with T4B HCC disease (32). Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had uncertain diagnoses (i.e., dysplastic nodule vs. tumor), incomplete records due to loss to follow-up, or the inability to complete planned treatment at our transplant center due to social issues like insurance, moving, or incarceration.

In order to further evaluate HCC patient survival after transplant using this multimodality therapy approach, comparisons were made with two non-cancer control subsets at our transplant center. The first control subset included transplanted cirrhotic patients without HCC who were matched on the basis of recipient age, race and specific disease etiology. Patients were propensity matched 1:2 to controls as long as similar patients were present in our transplant registry. This served to compare outcomes to matched non-HCC recipients with similar demographics and disease etiology. The second control subset consisted of transplanted cirrhotic patients without HCC who had a pre-transplant MELD score of 21-24 and diagnosis of hepatitis C cirrhosis. This control group was chosen due to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) HCC MELD exception policy of adjusting the MELD score to match MELD score of 21-24. This second control group was to serve as a comparison to non-HCC liver transplant recipients with similar MELD score at match. Achieving exact equivalence of patient numbers across groups was not possible due to insufficient numbers of patients fitting certain match criteria in our registry.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in demographics and treatments were evaluated with chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Predictors of survival from diagnosis were determined using multivariate Cox proportional hazard modeling, and likelihood of progression to transplant was evaluated using logistic regression modeling. Variables evaluated included age, stage, race, gender, number of treatments, type of treatment, cirrhosis, AFP, disease etiology, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and use of alcohol, tobacco, or drugs. Kaplan-Meier survival curves illustrate survival after transplantation and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Acknowledgements

We thank our patients and their families for their trust and dedication to the intense follow-up that made this study possible.

Abbreviations

- AFP

Alpha-fetoprotein

- CFT

Contraindicated for transplant

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR

Hazard ratio

- ITT

Intention-to-treat with transplant

- ITT/Tx

Intention-to-treat with transplant and transplanted

- ITT/No Tx

Intention-to-treat with transplant and not transplanted

- MELD

Model for end-stage liver disease

- MMT

Multimodality therapy

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- RFA

Radiofrequency ablation

- TACE

Transarterial chemoembolization

- TACI

Transarterial chemoinfusion

- Y-90

Yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization

Footnotes

Rajesh Ramanathan participated in the writing of the paper and data analysis

Amit Sharma participated in the writing of the paper and performance of the research

David Lee participated in the writing of the paper, data analysis and performance of the research

Martha Behnke participated in the writing of the paper and data analysis

Karen Bornstein participated in the performance of the research

R Todd Stravitz participated in the research design and performance of the research

Malcolm Sydnor participated in the research design and performance of the research

Ann Fulcher participated in the research design, performance of the research and edited the manuscript

Adrian Cotterell participated in the performance of the research

Marc P Posner participated in the performance of the research

Robert A Fisher participated in the research design, writing of the paper, data analysis and performance of the research

Disclosures

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Di Bisceglie AM, Rustgi VK, Hoofnagle JH, Dusheiko GM, Lotze MT. NIH conference. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann.Intern.Med. 1988;108:390. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin.Liver Dis. 1999;19:329. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N.Engl.J.Med. 1996;334:693. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halazun KJ, Verna E, Samstein B, et al. Priority pass to death - prioritization of liver transplant for HCC worsens survival. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:5, 46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts JP, Venook A, Kerlan R, Yao F. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Ablate and wait versus rapid transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:925. doi: 10.1002/lt.22103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao FY, Kerlan RK, Jr, Hirose R, et al. Excellent outcome following down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation: an intention-to-treat analysis. Hepatology. 2008;48:819. doi: 10.1002/hep.22412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma P, Welch K, Hussain H, et al. Incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation in the MELD era. Dig.Dis.Sci. 2012;57:806. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1910-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, et al. Prognostic factors for tumor recurrence after a 12-year, single-center experience of liver transplantations in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J.Transplant. 2010. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/904152. 10.1155/2010/904152. Epub 2010 Aug 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin WY, Suh KS, Lee HW, et al. Prognostic factors affecting survival after recurrence in adult living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:678. doi: 10.1002/lt.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha BY, Ahmed A, Sze DY, et al. Long-term survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transcatheter arterial chemoinfusion. Aliment.Pharmacol.Ther. 2007;26:839. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Luna W, Sze DY, Ahmed A, et al. Transarterial chemoinfusion for hepatocellular carcinoma as downstaging therapy and a bridge toward liver transplantation. Am.J.Transplant. 2009;9:1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lammer J, Malagari K, Vogl T, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc.Intervent.Radiol. 2010;33:41. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archer KJ, Zhao Z, Guennel T, Maluf DG, Fisher RA, Mas VR. Identifying genes progressively silenced in preneoplastic and neoplastic liver tissues. Int.J.Comput.Biol.Drug Des. 2010;3:52. doi: 10.1504/IJCBDD.2010.034499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mas VR, Fisher RA, Archer KJ, et al. Genes associated with progression and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C patients waiting and undergoing liver transplantation: preliminary results. Transplantation. 2007;83:973. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258643.05294.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behnke MK, Reimers M, Fisher RA. Stem cell and hepatocyte proliferation in Hepatitis C Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: transplant implications. Ann. Hepatol. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong J, Kong L, Kong J, et al. After insufficient radiofrequency ablation, tumor-associated endothelial cells exhibit enhanced angiogenesis and promote invasiveness of residual hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2012:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong ZP, Huang F, Lu MH. Association between insulin-like growth factor-2 expression and prognosis after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and octreotide in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian Pac.J.Cancer.Prev. 2012;13:3191. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.7.3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DuBay D, Sandroussi C, Sandhu L, et al. Liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using poor tumor differentiation on biopsy as an exclusion criterion. Ann.Surg. 2011;253:166. doi: 10.1097/sla.0b013e31820508f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin.Liver Dis. 2005;25:181. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-871198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuks D, Dokmak S, Paradis V, Diouf M, Durand F, Belghiti J. Benefit of initial resection of hepatocellular carcinoma followed by transplantation in case of recurrence: an intention-to-treat analysis. Hepatology. 2012;55:132. doi: 10.1002/hep.24680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fong Y, Sun RL, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. An analysis of 412 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma at a Western center. Ann.Surg. 1999;229:790. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bismuth H, Chiche L, Adam R, Castaing D, Diamond T, Dennison A. Liver resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Ann.Surg. 1993;218:145. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Intention-to-treat analysis of surgical treatment for early hepatocellular carcinoma: resection versus transplantation. Hepatology. 1999;30:1434. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, Guidinger MK, Merion RM. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1033. doi: 10.1002/lt.22108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu JC, Neugut AI, Wang S, et al. Racial and insurance disparities in the receipt of transplant among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:1801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon-Weeks AN, Snaith A, Petrinic T, Friend PJ, Burls A, Silva MA. Systematic review of outcome of downstaging hepatocellular cancer before liver transplantation in patients outside the Milan criteria. Br.J.Surg. 2011;98:1201. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washburn K. Model for End Stage Liver Disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a moving target. Transplant.Rev.(Orlando) 2010;24:11. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulcher AS, Turner MA, Capps GW, Zfass AM, Baker KM. Half-Fourier RARE MR cholangiopancreatography: experience in 300 subjects. Radiology. 1998;207:21. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.1.9530295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marano I, Della Noce M, Stagni V, et al. Magnetic resonance in surgical planning in hepatocarcinomas. Radiol.Med. 1995;89:94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Liver Tumor Study Group A randomized prospective multi-institutional trial of orthotopic liver transplantation or partial hepatic resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Investigators’ booklet and protocol. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher RA, Maluf DG, Wolfe L, et al. Is hepatic transplantation justified for primary liver cancer? J.Surg.Oncol. 2007;95:674. doi: 10.1002/jso.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher RA, Maluf D, Cotterell AH, et al. Non-resective ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: effectiveness measured by intention-to-treat and dropout from liver transplant waiting list. Clin.Transplant. 2004;18:502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher RA, Maroney TP, Fulcher AS, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: strategy for optimizing surgical resection, transplantation and palliation. 16. Clin.Transplant. 2002;(Suppl 7):52. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.16.s7.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher RA, Maluf D, Cotterell AH, et al. Non-resective ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: effectiveness measured by intention-to-treat and dropout from liver transplant waiting list. Clin.Transplant. 2004;18:502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]