Abstract

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) amplifies the inflammatory response and plays a role in cancer and sepsis. Inhibition of TREM-1 by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) in macrophages suppresses cancer cell invasion in vitro. In the clinical setting, high levels of TREM-1 expression on tumor-associated macrophages are associated with cancer recurrence and poor survival of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). TREM-1 upregulation on peritoneal neutrophils has been found in human sepsis patients and in mice with experimental lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced septic shock. However, the precise function of TREM-1 and the nature of its ligand are not yet known. In this study, we used the signaling chain homooligomerization (SCHOOL) model of immune signaling to design a novel, ligand-independent peptide-based TREM-1 inhibitor and demonstrated that this peptide specifically silences TREM-1 signaling in vitro and in vivo. Utilizing two human lung tumor xenograft nude mouse models (H292 and A549) and mice with LPS-induced sepsis, we show for the first time that blockade of TREM-1 function using non-toxic and non-immunogenic SCHOOL peptide inhibitors: 1) delays tumor growth in xenograft models of human NSCLC, 2) prolongs survival of mice with LPS-induced septic shock, and 3) substantially decreases cytokine production in vitro and in vivo. In addition, targeted delivery of SCHOOL peptides to macrophages utilizing lipoprotein-mimicking nanoparticles significantly increased peptide half-life and dosage efficacy. Together, the results suggest that ligand-independent modulation of TREM-1 function using small synthetic peptides might be a suitable treatment for sepsis and NSCLC and possibly other types of inflammation-associated disorders.

Keywords: Macrophage, TREM-1 receptor, SCHOOL model of cell signaling, therapeutic peptides, non-small cell lung cancer, sepsis, nanoparticles, targeted delivery

1. Introduction

Macrophages play an important role in such seemingly disparate disorders as cancer and sepsis. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide and is broadly divided into two classes – non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer. Despite advances made in chemotherapy [1], NSCLC is responsible for over 1.1 million deaths annually worldwide, and the 5- year survival rate for patients with NSCLC is only 15% [2]. The infiltrate of most tumors, including NSCLC, contains tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [3]. TAMs secrete a variety of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and enzymes that regulate tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [4]. High macrophage infiltration into the tumor mass correlates with the promotion of tumor growth and metastasis [3] and is associated with poor prognosis in NSCLC [5]. TAM recruitment, activation, growth and differentiation are regulated by macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) [6]. Increased pretreatment serum M-CSF level is a significant independent predictor of poor survival in patients with NSCLC [7]. Similar to their role in cancer, macrophages are critically involved in the pathogenesis of sepsis, a complex clinical syndrome that results from the systemic response to infection and is characterized by overwhelming production of proinflammatory cytokines [8]. Despite the use of potent antibiotics and advanced resuscitative equipment costing $17 billion annually, sepsis kills about 375,000 Americans each year and mortality rates for patients with septic shock approach nearly 50% [9]. Currently, no approved sepsis drugs are available and over 30 drug candidates have failed late-stage clinical trials. In septic mice, macrophages secrete high levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL- 1 [10]. In patients with sepsis, M-CSF is overproduced [11]. Furthermore, elevated levels of TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines are closely linked with poor patient outcome [12]. Taken together, this highlights the urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches to treat NSCLC and sepsis and suggests the macrophage as a promising therapeutic target for these disorders.

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (TREM-1) mediates the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and plays a role in a variety of inflammation-associated disorders [13–16]. TREM-1 activation preferentially induces M-CSF expression [17], further suggesting an important role of TREM-1 in cancer and sepsis. In patients with NSCLC, TREM-1 expression on TAMs is associated with cancer recurrence and poor survival: patients with low TREM-1 expression have a 4-year survival rate of over 60%, compared with less than 20% for patients with high TREM-1 expression [18]. In patients with sepsis, TREM-1 expression on macrophages is markedly increased [19–20]. Blockade of TREM-1 in septic mice lowers expression levels of TNF-α and IL-6 and increases survival from 5-10% in control animals to 70-80% in treated animals [13,21–22]. Together, these results implicate TREM-1 as a promising target for the development of new rational therapeutics for cancer and sepsis.

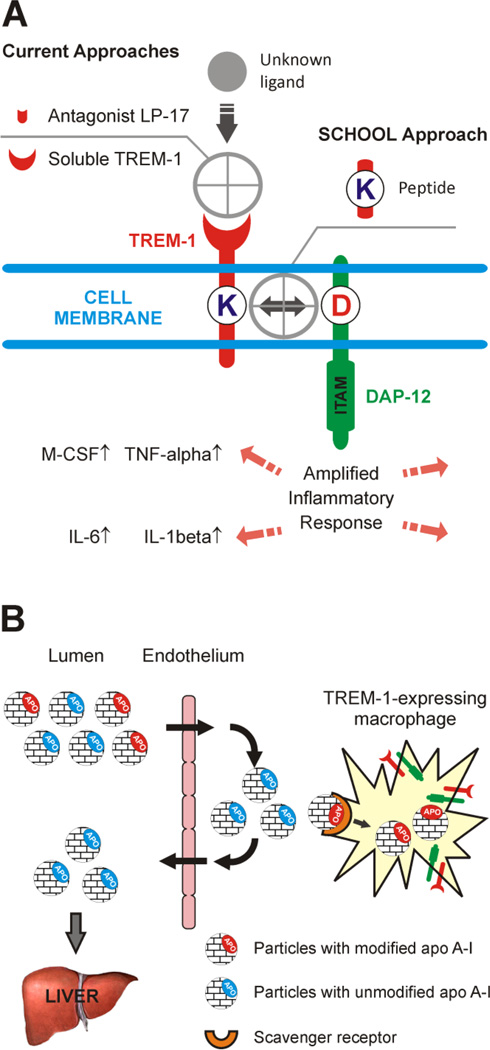

Current strategies to inhibit TREM-1 include the use of either a TREM-1 receptor decoy or a TREM-1 antagonist LP-17 (Fig. 1A) [13, 15, 23–24]. While the natural TREM-1 ligand is not yet known, based on a new model of immune signaling, the signaling chain homooligomerization (SCHOOL) model [25], we have developed a novel, ligand-independent approach to TREM-1 inhibition (Fig. 1A). We hypothesize that blockade of TREM-1 using synthetic SCHOOL peptides would attenuate the specific inflammatory response and improve treatments for NSCLC and sepsis. We also hypothesize that macrophage-targeted lipoprotein nanoparticles that mimic human high density lipoproteins (HDL) will be beneficial for targeted delivery of these peptide inhibitors to TREM-1-expressing macrophages (Fig. 1B). The aim of this study was to answer the following questions: 1) whether treatment using a TREM-1-specific SCHOOL peptide GF9 specifically silences TREM-1 signaling in vitro and in vivo; 2) whether GF9 treatment shows antitumor activity in NSCLC xenografts; 3) whether GF9 treatment protects mice from LPS-induced septic shock; and 4) whether targeted delivery of GF9 to macrophages using synthetic HDL nanoparticles reduces the effective peptide dosage and improves half-life. Our results provide for the first time evidence that TREM-1 blockade using a novel mechanism-based inhibitory peptide in free and nanoparticle-encapsulated forms suppresses tumor growth in the H292 and A549 lung tumor xenografts and improves survival of septic mice.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the proposed concepts. (A) Inhibiting TREM-1 by synthetic peptides designed using a novel model of immune signaling, the Signaling Chain HOmoOLigomerization (SCHOOL) model. In contrast to current approaches, these inhibitors employ ligand-independent mechanisms of action and block transmembrane interactions between TREM-1 and its signaling partner, DAP-12. (B) Targeting high density lipoproteins (HDL) to macrophages by using a specific and naturally occurring modification (sulfoxidation) of the HDL major protein, apolipoprotein (apo) A-I. In the human body, native unmodified HDL (depicted by blue) function to deliver excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues to the liver and are not normally uptaken by macrophages. In contrast, synthetic HDL containing oxidized apo A-I or its peptides (depicted by red) are uptaken by macrophages, thus delivering the incorporated payload(s) directly to the cells of interest. Abbreviations: apo, apolipoprotein; DAP-12, DNAX activation protein of 12 kDa; IL, interleukin; ITAM, immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif; M-CSF, macrophage colony-stimulating factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals, Lipids and Cells

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1'-rac-glycerol) (DMPG), 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (rhodamine-PE, Rho B-PE) and egg yolk L-α-phosphatidyl choline (egg-PC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Sodium cholate, cholesterol, cholesteryl oleate, hydrogen peroxide and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). The murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA).

2.2. Peptides and proteins

The following synthetic peptides were ordered from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA): TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GLLSKSLVF (the TREM-1213-221, GF9) composed exclusively of L- or D-amino acids (GF9 and GF9-d, respectively), control peptide GLLSGSLVF (GF9-G), and two 22-mer peptides PYLDDFQKKWQEEMELYRQKVE (H4) and PLGEEMRDRARAHVDALRTHLA (H6) that correspond to human apolipoprotein (apo) A-I helixes 4 and 6, respectively. Native apo A-I was purified from human serum as previously described [26]. Unmodified apo A-I protein was isolated from the initial preparation by preparative RP-HPLC as described [27]. Protein composition of peaks in the HPLC profile was determined by SDS-PAGE (12.5% acrylamide) using the standard Laemmli system [28] as well as by analytical RP-HPLC as previously described [27]. Oxidized apo A-I containing sulfoxides at methionines 112 and 148 was prepared, purified and characterized as described previously [27]. The same procedure was used to oxidize methionine residues in synthetic peptides H4 and H6.

2.3. Discoidal and spherical lipoproteins

The peptide (Pep)-containing discoidal HDL (Pep-dHDL, where Pep is GF9 or GF9-G) complexes were synthesized essentially as described [29–30] except that no dialysis was undertaken [31]. The molar ratio was 65:25:3:1 for DMPC:DMPG:Pep:apo A-I. Briefly, DMPC and DMPG in organic solvents were mixed, dried in a stream of argon, and placed under vacuum for 8 h. To synthesize fluorescently labeled nanoparticles, rhodamine B-PE in chloroform was also added to a lipid mixture. Then, lipid films were dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, sonicated for 5 min, and GF9 or GF9-G in aqueous solution of propylene glycol, ethanol, and Tween-80 was added. Amount of peptide was controllably varied in different preparations. After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, solution containing either oxidized or unmodified apo A-I in PBS, pH 7.4 was added and the mixture was incubated at 30°C for 3 h. The same procedure was used to prepare Pep-dHDL with a 1:1 mixture of apo A-I peptides H4 and H6 in either oxidized or unmodified form.

The Pep-containing spherical HDL (Pep-sHDL) complexes were synthesized by the sodium cholate dialysis procedure essentially as described [32]. The molar ratio was 125:6:2:3:1:210 for egg-PC:cholesterol:cholesteryl oleate:Pep:apo A-I:sodium cholate. Briefly, egg-PC, cholesterol, and cholesteryl oleate in organic solvents were mixed, dried in a stream of argon, and placed under vacuum for 8 h. To synthesize fluorescently labeled nanoparticles, rhodamine B-PE in chloroform was also added to a lipid mixture. Then, lipid films were dispersed in Tris-buffered saline-EDTA (TBS-EDTA, pH 7.4) and sonicated for 5 min. To the dispersed lipids, GF9 or GF9-G in aqueous solution of propylene glycol, ethanol, and Tween-80 was added. Amount of peptide was controllably varied in different preparations. Then, sodium cholate solution was added and the mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30 min. After cooling to 30°C, solution containing either oxidized or unoxidized apo A-I in PBS, pH 7.4 was added and the mixture was incubated at 30°C for 3 h, followed by extensive dialysis against PBS to remove sodium cholate. The same procedure was used to prepare Pep-sHDL with a 1:1 mixture of apo A-I peptides H4 and H6 in either oxidized or unmodified form.

The obtained Pep-HDL particles were then purified on a calibrated Superdex 200 HR gel filtration column (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) using the BioCAD 700E Workstation (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and characterized by analytical RP-HPLC and non-denaturing gel electrophoresis as described previously [30]. Protein concentrations in the Pep-HDL particles were measured using the Lowry method as modified by Markwell et al [33]. Final protein compositions were determined in the prepared particles by analytical RP-HPLC as previously described [30]. Total cholesterol was determined enzymatically using a Boehringer-Mannheim kit and the manufacturer’s suggested procedure. Phospholipids were determined by a phosphorus assay [34]. The mean size of the particles was determined using electron microscopy (EM) essentially as described [30–31]. Briefly, the Pep-HDL complexes (at a concentration of about 0.3 mg of protein/ml) were extensively dialyzed against 5 mM ammonium bicarbonate, mixed with the same volume of 2% phosphotungstate, pH 7.4, and examined using a FEI Tecnai 12 Spirit BioTwin transmission electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR) at 80 KV accelerating voltage on carbon-coated Formvar grids. Microphotographs were photographed at an instrument magnification of 87000× and 92000×, and mean particle dimensions of 100 particles were determined from each negative.

2.4. In vitro macrophage uptake assay

In vitro experiments for quantifying macrophage uptake of the fluorescent Pep-HDL complexes were performed as described [31]. Briefly, the BALB/c murine macrophage J774A.1 cells (ATCC TIB-67) were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc, Manassas, VA) with 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc, Manassas, VA) and grown to approximately 90% of confluence in 6-well tissue culture plates (Corning, Tewksbury, MA). Cells were incubated for varied time periods from 4 to 24 h at 37°C with fluorescently labeled Pep-HDL nanoparticles containing apo A-I or peptides H4 and H6 in either oxidized or unmodified form at a concentration of 4 µM Rho-B. Stability studies revealed that both discoidal and spherical Pep-HDL are stable under these conditions for at least 48 hours. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed using Promega passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI). The rhodamine B fluorescence was measured in the lysates with a 540 nm excitation and a 590 nm emission filters using the Gemini EM fluorescence microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The protein concentration in the lysates was determined using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) and the SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

2.5. In vitro cytokine release

J774 macrophages were cultured in 48-well plates (Corning, Cambridge, MA) for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of LPS (1 µg/ml, Escherichia coli 055:B5, Sigma) in combination with 50 ng/ml control peptide GF9-G or TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in either free or HDL-bound form. Cell viability was determined using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiozol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays (Sigma) in 96-well plates, as described [35]. Untreated cells and cells treated with 1% Triton X-100 were used as negative and positive controls of cytotoxicity, respectively. No effect of the tested agents was observed on cell viability. Cell-free supernatants were harvested and stored at - 20°C for later cytokine quantification. TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β were assayed using commercial ELISA kits (Pierce Biotechnology, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, lL) according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

2.6. Tumor xenografts in nude mice and in vivo tumor growth

Animal efficacy studies were performed using female 6-8 week old NU/J mice from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were handled as specified in the USDA Animal Welfare Act (9 CFR, Parts 1, 2, and 3) and as described in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Research Council. The animal protocols and procedures were approved by the VIVOPATH Animal Care and Use Committee. Human lung carcinoma cell lines H292 and A549 were obtained from ATCC. Tumor cells in culture were harvested and resuspended in a 1:1 ratio of RPMI 1640 and Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). NSCLC xenografts were established by injecting subcutaneously into the right flanks 5 ×106 viable cells per mouse. Tumor volumes were calculated with caliper measurements using the formula V = π/6 (length ×width × width). When tumor volumes reached an average of 200 mm3, tumor-bearing animals were randomized into groups of 10, and dosing was initiated. All formulations were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected at indicated doses and administration schedule. Clinical observations, body weights and tumor volume measurements were made 3 times weekly. Data points represent mean tumor volume ± SEM. Antitumor effects are expressed as the percentage of T/C (treated versus control), dividing the tumor volumes from treatment groups with the control groups and multiplied by 100. According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) standards, a % T/C ≤ 42 is indicative of antitumor activity [36]. At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed and the tumors were excised and weighed.

2.7. Mouse model of LPS-induced endotoxemia

Naïve, female C57BL/6 mice at 8 to 10 weeks of age (18 to 21 g) from the Jackson Laboratory were randomly grouped (10 mice per group) and i.p. injected with vehicle or the indicated doses of dexamethasone (DEX), control peptide GF9-G and TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in either free or HDL-bound form. One hour later, mice received i.p. injection of 30 mg/kg LPS from E. coli 055:B5 (Sigma). In some experiments, all formulations were i.p. administered 1 and 3 h after LPS injection. The viability of mice was examined hourly. Body weights were measured daily. In all of the animal experiments, blood samples were collected via a sub-mandibular (cheek) bleed at 90 min after administration of LPS. The animal protocols and procedures were approved in advance by the VIVOPATH Animal Care and Use Committee. The production of cytokines in serum was measured by a standard sandwich cytokine ELISA procedure using TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 ELISA kits (Pierce Biotechnology, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

2.8. Mouse tolerability

Experiments were done according to the animal protocols and procedures approved by the VIVOPATH Animal Care and Use Committee. Mouse tolerability studies were performed using naïve, female C57BL/6 mice at 8 to 10 weeks of age (18 to 21 g) from the Jackson Laboratory. Animals were randomly grouped (5 mice per group) and i.p. injected with indicated doses of TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free form. Clinical observations and body weights were made twice daily.

2.9. Statistics

Tumor volumes were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. Statistical analysis of survival curves was performed by the Kaplan-Meier test. Comparisons were made using two-tailed Student’s t test. Statistical significances in in vitro macrophage uptake assay and cytokine analysis ELISA data were determined by two-tailed Student’s t test. *, P = 0.05 to 0.01 (significant); **, P = 0.01 to 0.001 (very significant); ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001 (extremely significant); and ****, P < 0.0001 (extremely significant). For all analyses, the GraphPad Prism software program (v.6; GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA) was used.

3. Results

3.1. Incorporation of TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 into HDL

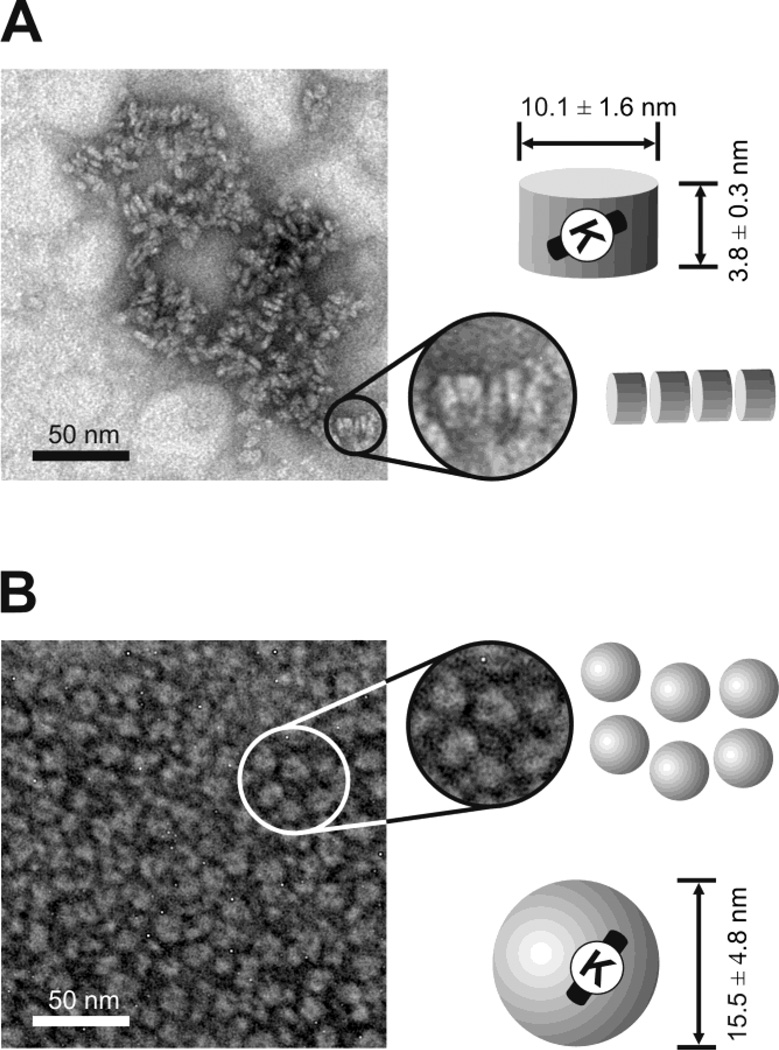

In order to test whether GF9 can be incorporated into a HDL-mimicking delivery platform to increase peptide half-life and dosage efficacy, we synthesized and characterized both discoidal and spherical HDL-like nanoparticles that contain GF9 (Pep-HDL). We also used a naturally occurring oxidation of the major HDL protein, apo A-I, to target HDL to macrophages (Fig. 1B). In a subset of experiments, an equimolar mixture of either unmodified or oxidized synthetic apo A-I peptides H4 and H6 was used instead of the native apo A-I protein. To test if oxidation of apo A-I or its peptides affects the size or composition of Pep-HDL for targeted delivery, we examined all synthesized Pep- HDL by EM. EM imaging showed no significant dependence of apparent particle size or shape on the apo A-I protein/peptide oxidation status. The discoidal Pep-HDL particles reconstituted using unmodified apo A-I had a mean diameter of 10.1 ± 1.6 and a mean height of 3.8 ± 0.3 (Fig. 2A), which was not significantly different from the size of Pep-HDL with oxidized apo A-I: 10.7 ± 1.8 and 4.4 ± 1.5, respectively (not shown). Spherical Pep-HDL that contain unmodified apo A-I had a mean particle size of 15.5 ± 4.8 (Fig. 2B), which was not significantly different from the size of Pep- HDL with its oxidized counterpart: 14.7 ± 3.6 (not shown). The discoidal and spherical Pep-HDL complexes reconstituted using a 1:1 mixture of either unmodified or oxidized peptides H4 and H6 had morphologies and particle sizes similar to those of Pep-HDL complexes containing apo A-I (not shown), suggesting that these peptides can functionally replace the native apo A-I protein with respect to their ability to assist in the self-assembly of HDL-like particles. All reconstituted discoidal Pep-HDL complexes had a similar ability to arrange in characteristic stacks (Fig. 2A). These observations are consistent with the results published before for reconstituted HDL [30] and HDL complexes that contain imaging probes [31, 37], the chemotherapy drug paclitaxel (PTX) [32] or the polyene antibiotic amphotericin B [29]. We have previously reported that oxidation of apo A-I does not significantly affect its ability to bind lipid or reconstitute into HDL-like particles [30]. Consistent with these findings, we did not observe any significant differences in lipid and protein composition or peptide-carrying capacity between the reconstituted Pep-HDL particles with unmodified or oxidized apo A-I (data not shown). We have also found that both unmodified and oxidized synthetic 22-mer peptides H4 and H6 may substitute for apo A-I to accommodate Pep- HDL without altering the overall lipid and peptide composition of the particles (results are not shown).

Figure 2.

Representative electron microscopy images of HDL of discoidal (A) and spherical (B) morphology that contain the incorporated TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9. Characteristic rouleaux (depicted by circles and zoomed in on the right panels) are found in disc-shaped HDL particles (A). Particles with unmodified apo A-I are shown for illustrative purposes. Similar shape, size and size distribution are observed for HDL with oxidized apo A-I or its unmodified and oxidized peptides. Abbreviations: apo, apolipoprotein; high density lipoproteins, HDL; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

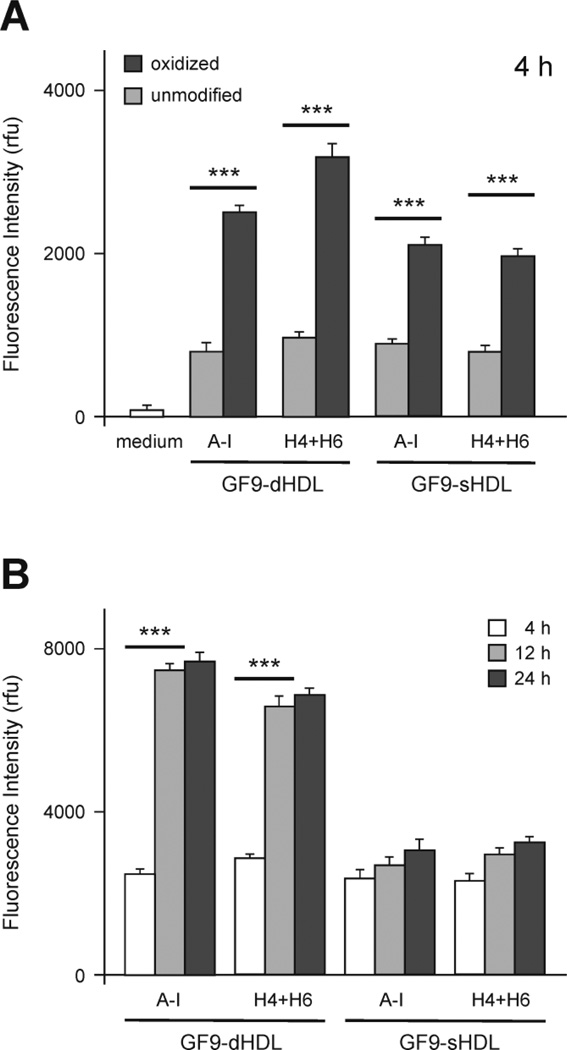

3.2. Oxidation of Apo A-I or its peptides enhances in vitro macrophage uptake of GF9-HDL

In order to study in vitro macrophage uptake, we tested the discoidal and spherical HDL formulations that contain GF9 and rhodamine B-labeled lipid using the established J774 macrophage line. Fluorescence intensities were measured in J774 cell lysates after a 4 h incubation with the HDL formulations and the values were normalized to total cell protein content (Fig. 3A). Macrophage uptake of discoidal and spherical GF9-HDL containing oxidized apo A-I or a 1:1 mixture of oxidized peptides H4 and H6 is significantly higher (P = 0.0001 to 0.001) as compared to their unmodified counterparts (Fig. 3A). This finding not only indicates that oxidation of methionines within the apo A-I protein/peptide components targets HDL to macrophages, but also suggests that synthetic peptides H4 and H6 can be used as a substitute for apo A-I, while maintaining full functionality of HDL. In contrast to spherical GF9-HDL containing oxidized apo A-I or its peptides, macrophage uptake of GF9-HDL of discoidal morphology significantly increases with extended incubation times (Fig. 3B, P = 0.0001 to 0.001), suggesting different kinetic parameters. In summary, these findings are consistent with our previous data reported for imaging probe-containing HDL [31] and together confirm that: 1) specific oxidation of apo A-I significantly increases the in vitro macrophage uptake of HDL and 2) similar to native apo A-I, synthetic peptides H4 and H6 not only assist in the self-assembly of the reconstituted HDL particle, but can also target particles to macrophages upon oxidation of key methionine residues.

Figure 3.

Oxidation of apo A-I or synthetic apo A-I peptides enhances in vitro macrophage uptake of HDL that contain the incorporated TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9. (A) Mean fluorescence intensities of cell lysates normalized to cell protein content (mean ± SD, n = 3): J774 macrophages were incubated at 37°C for 4 h with medium only (white bars) or with 4 µM Rho-B fluorescent GF9-HDL(A-I) or GF9-HDL(H4+H6) of discoidal or spherical morphology. Unmodified and oxidized protein/peptide species are depicted by light and dark gray bars, respectively. ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001 as compared with unmodified apo A-I protein/peptides. (B) Mean fluorescence intensities of cell lysates normalized to cell protein content (mean ± SD, n = 3): J774 macrophages were incubated at 37°C for 4, 12 and 24 h (white, light gray and dark gray bars, respectively) with 4 µM Rho-B fluorescent GF9-HDL(A-I) or GF9-HDL(H4+H6) of discoidal or spherical morphology that contain oxidized apo A-I or its peptides, H4 and H6. ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001 as compared with 4 h time point. Abbreviations: apo, apolipoprotein; high density lipoproteins, HDL; HDL(A-I), HDL with apo A-I; HDL(H4+H6), HDL with a 1:1 mixture of synthetic peptides H4 and H6 that correspond to apo A-I helixes 4 and 6, respectively; dHDL and sHDL, discoidal and spherical HDL, respectively; Rho-B, rhodamine B; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

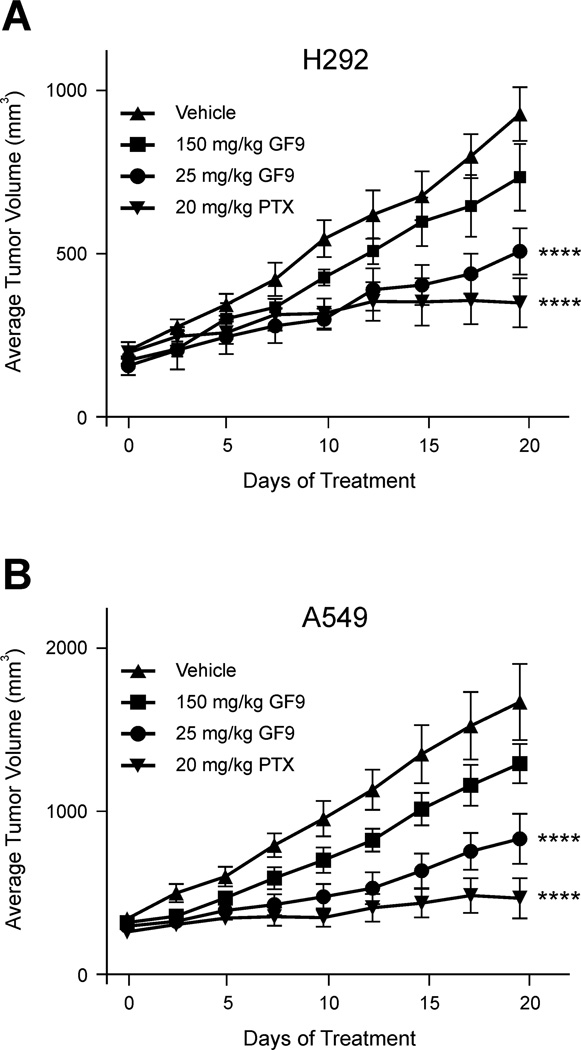

3.3. Effect of GF9 in free and HDL-bound form on growth of human NSCLC xenografts

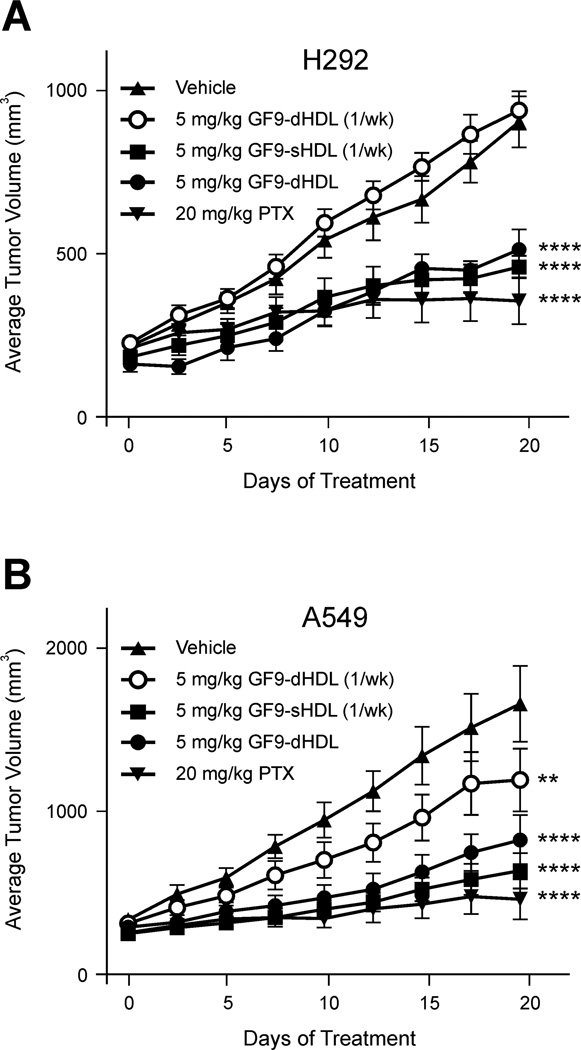

To evaluate an antitumor response to TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free and HDL-bound form, two human NSCLC cell lines, the squamous H292 and adenocarcinoma A549 cell lines, were established as subcutaneous xenograft models in nude mice. When administered twice a week at a dose of 25 mg/kg, GF9 showed antitumor efficacy in both models (Fig. 4), with the effect more pronounced in the A549 model (31% T/C vs. 52% T/C for the H292 model). The observed antitumor effect of 25 mg/kg GF9 is specific: administration of the control peptide GF9-G at the same dose did not affect tumor growth (not shown). Surprisingly, administration of GF9 twice a week at a much higher dose of 150 mg/kg did not significantly inhibit tumor growth in both xenograft models (Fig. 4). Although the underlying molecular mechanisms of this phenomenon are incompletely understood and need to be further investigated, one can hypothesize that this results from excessive immunomodulation at high concentrations of GF9. This effect will be discussed in more detail later in this paper.

Figure 4.

The TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free form inhibits tumor growth in the H292 (A) and A549 (B) xenograft mouse models of NSCLC. H292 or A549 cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice with randomization (n = 10) once tumors reached an average of 200 mm3. Vehicle, paclitaxel (PTX) as a positive control, and GF9 peptide were all intraperitoneally administered twice a week. Bars, SEM. For statistical analysis, each treatment was compared with the vehicle control using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. ****, P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

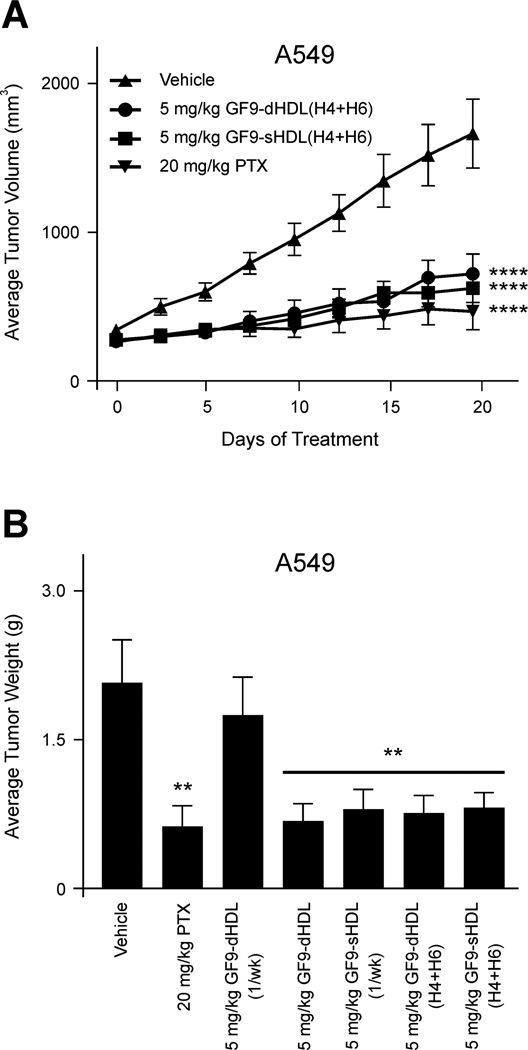

To evaluate whether targeted delivery of TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 to macrophages using HDL-like synthetic nanoparticles reduces the effective dosage of the peptide and improves its circulatory half-life, H292 and A549 xenografts were administered once or twice a week with the same dose of 5 mg/kg of GF9. The peptide was administered in either free form or in discoidal or spherical HDL-bound form (GF9-dHDL and GF9-sHDL, respectively) that contain oxidized apo A-I or its oxidized peptides H4 and H6 (Figs. 5 and 6). The results indicate that GF9 in free form (administered twice a week, not shown) and GF9-dHDL (administered once a week) had no effect on tumor growth in both xenograft models (Fig. 5). On the contrary, strong inhibition of tumor growth was observed for GF9-dHDL (administered twice a week) and GF9-sHDL (administered once a week) up to day 19 with 40 and 41% T/C (H292; Fig. 5A) and 29 and 27% T/C (A549; Fig. 5B), respectively. Considering that the in vivo peptide half-life is short, typically a few minutes, [38] these data provide evidence that incorporation of GF9 into dHDL and sHDL with half-lives of 12-20 hrs and 3-5 days, respectively [39–40], can prolong the circulatory half-life and reduce the effective dosage of peptide. Further, the longer half-life of GF9-sHDL as compared to GF9-dHDL can explain the observed differences in tumor growth between groups treated with GF9-sHDL and GF9-dHDL when both formulations were administered once a week (Fig. 5). Consistent with this hypothesis, administration of GF9-dHDL twice a week results in strong inhibition of tumor growth (Fig. 5). Interestingly, when administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg twice a week, the GF9-d peptide composed of D-amino acids reached an antitumor effect of 32% T/C in A549 xenografts (not shown), which may be also explained by the longer plasma half-life of GF9-d as compared to its L-counterpart. As illustrated for the A549 xenograft model, no significant difference in antitumor activity was observed for GF9 incorporated into discoidal and spherical HDL containing either oxidized apo A-I or an equimolar mixture of its oxidized peptides H4 and H6 (Figs. 5B and 6A). Further, when administered twice a week at a dose of 5 mg/kg, GF9-dHDL and GF9-sHDL containing a 1:1 mixture of oxidized peptides H4 and H6 showed an antitumor effect of 28% and 26% T/C, respectively (Fig. 6A). In A549 xenografts, inhibition of tumor growth was determined by measurements of not only tumor volume but also tumor weight (Fig. 6B). The final tumor volumes after 19 days of i.p. administration (Figs. 5 and 6A) were found to be consistent with the weights of the excised tumors postnecropsy. Control tumors weighed 1.9 ± 0.4 g (mean ± SEM), whereas mice treated with 5 mg/kg i.p. TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 bound to dHDL or sHDL containing either oxidized apo A-I or its oxidized peptides H4 and H6 had tumors which weighed significantly less (P = 0.001 to 0.01) with the exception of mice receiving GF9-dHDL treatment once a week.

Figure 5.

The TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 incorporated into macrophage-targeted HDL that contain oxidized apo A-I inhibits tumor growth in the H292 (A) and A549 (B) xenograft mouse models of NSCLC. H292 or A549 cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice with randomization (n = 10) once tumors reached an average of 200 mm3. Vehicle (HDL containing no GF9) and paclitaxel (PTX) as a positive control were intraperitoneally administered twice a week, while GF9-dHDL and GF9-sHDL were all intraperitoneally administered twice or once (indicated as "1/wk") a week. Bars, SEM. For statistical analysis, each treatment was compared with the vehicle control using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. **, P = 0.01 to 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: apo, apolipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoproteins; dHDL and sHDL, discoidal and spherical HDL, respectively; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

Figure 6.

The TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 incorporated into macrophage-targeted HDL that contain an equimolar mixture of oxidized apo A-I peptides H4 and H6 inhibits tumor growth in the A549 xenograft mouse model of NSCLC. (A) A549 cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice with randomization (n = 10) once tumors reached an average of 200 mm3. Vehicle (HDL containing no GF9), paclitaxel (PTX) as a positive control, GF9-dHDL(H4+H6), and GF9- sHDL(H4+H6) were all intraperitoneally administered twice a week. Bars, SEM. For statistical analysis, each treatment was compared with the vehicle control using repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test. ****, P < 0.0001. (B) Average weights of excised tumors postnecroscopy from mice in each group treated with vehicle, PTX and GF9-HDL that contain either oxidized apo A-I or its oxidized peptides H4 and H6. Once a week administration is indicated as "1/wk". Bars, SEM. For statistical analysis, each treatment was compared with the vehicle control using Student’s t test. **, P = 0.001 to 0.01. Abbreviations: apo, apolipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoproteins; HDL(H4+H6), HDL with a 1:1 mixture of synthetic peptides H4 and H6 that correspond to apo A-I helixes 4 and 6, respectively; dHDL and sHDL, discoidal and spherical HDL, respectively; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

In summary, these data collectively indicate that TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide inhibitor GF9 generates a strong antitumor effect in the H292 and A549 xenograft mouse models of NSCLC. This finding is in line with recent research [24] suggesting that TREM-1 inhibition attenuates tumor growth within the colon. The antitumor effect observed for GF9 in both free and HDL-bound form suggests that this peptide can access its target site of action within the cell membrane (Fig. 1A) from both outside and inside the cell. Incorporation of GF9 into HDL-like synthetic particles substantially reduces the effective dosage of peptide probably because of the targeted delivery of the HDL-bound peptide to TREM-1-expressing macrophages and the prolonged circulatory half-life afforded by this strategy. Our results also support the finding that oxidized synthetic 22-mer peptides that correspond to amphipathic apo A-I helixes 4 and 6, are able to functionally replace native apo A-I in Pep-HDL, thereby significantly simplifying the nanoparticle preparation process and encouraging the further development of these therapeutic agents.

3.4. Effect of GF9 in free and HDL-bound form on lethality in endotoxemic mice

In order to investigate the effect of the TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free and HDL-bound form on lethality in septic mice, we used a mouse model of LPS-induced endotoxemia, which is a useful animal model to investigate the complex cytokine cascades involved in sepsis. Although the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model is often considered as a more clinically relevant model, no discrepancies between these two as well as other animal models of sepsis such as E. coli- or P. aeruginosa-induced peritonitis models were observed in previous studies using TREM-1 inhibitors [13, 21–22, 41–42], suggesting that if the effect is observed in a mouse model of LPS-induced endotoxemia, it is likely to be found in other animal models of sepsis, as well.

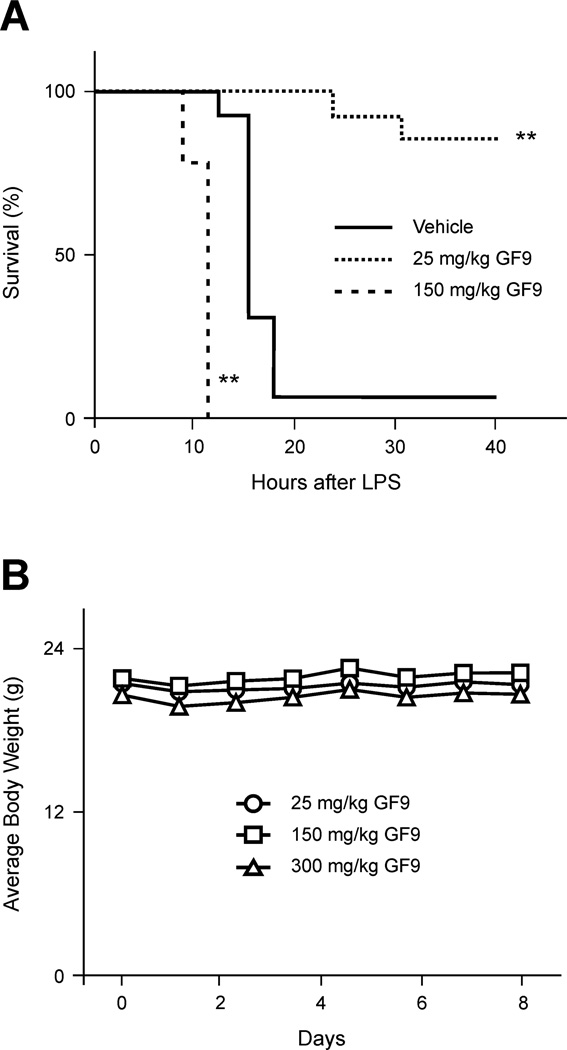

Treatment of mice with a single dose of 25 mg/kg GF9 in free form one hour prior to administration of a lethal dose of LPS rescued these animals (Fig. 7A), while administration of the control peptide GF9-G at the same dosage did not affect lethality (not shown). Surprisingly, administration of GF9 at a much higher dose of 150 mg/kg did not have a protective effect but instead, contributed to lethality, with death occurring significantly earlier (log-rank test, P = 0.001 to 0.01 as compared with vehicle-treated animals) (Fig. 7A). This effect is specific as administration of the GF9-G control peptide at 150 mg/kg dose did not affect lethality (not shown). We next tested whether GF9 is toxic and attempted to define a maximum tolerated dose in healthy naïve, female C57BL/6 mice. No weight loss occurred in mice even after a 300 mg/kg dose of GF9 (Fig. 7B), suggesting that this peptide is non-toxic and well-tolerated. This phenomenon is unusual but not unprecedented: in the bacterial peritonitis mouse model (but not in the LPS-induced endotoxic shock mouse model), partial silencing of TREM-1 using siRNA duplexes produced a significant survival benefit, while complete silencing of TREM-1 increased lethality [21].

Figure 7.

The TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free form prolongs survival of mice with LPS-induced septic shock at a dose of 25 mg/kg but contributes to death at a dose of 150 mg/kg, while being non-toxic in healthy mice up to a dose of 300 mg/kg. (A) C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) were intraperitoneally administered with vehicle or the indicated doses of GF9 peptide 1 h before LPS administration (30 mg/kg). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. **, P = 0.001 to 0.01 as compared with vehicle-treated animals. (B) The average weight of healthy C57BL/6 mice (n=5) intraperitoneally administered with the indicated doses of GF9 peptide in free form. Bars, SEM. Abbreviations: LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

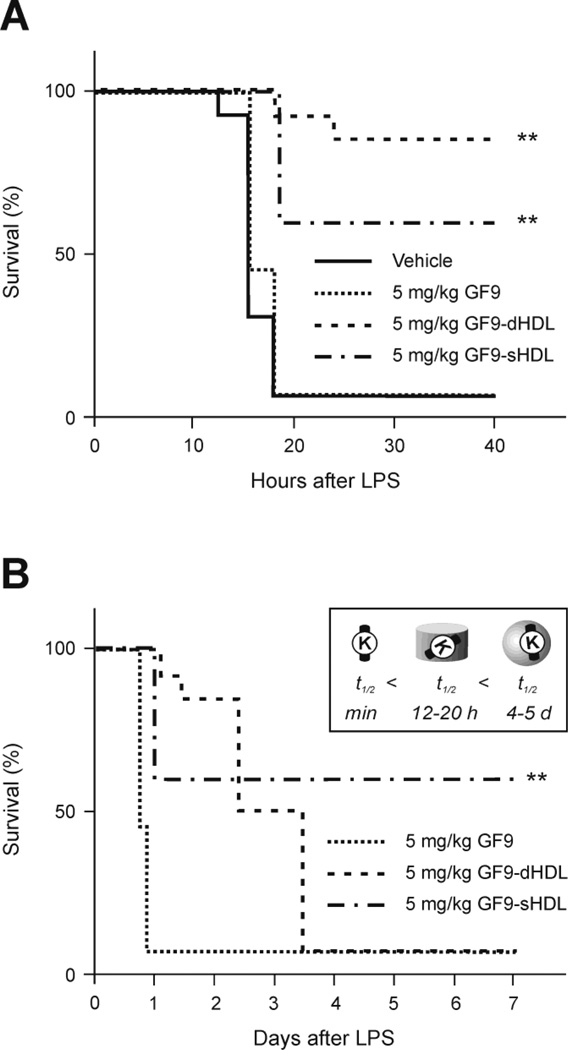

To evaluate whether incorporation of the TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 into macrophage-targeted HDL-like synthetic nanoparticles reduces the effective peptide dosage and improves circulatory half-life, mice were i.p. administered 1 h before LPS challenge with the same dose of 5 mg/kg of GF9 in free form or bound to discoidal or spherical HDL containing oxidized apo A-I (GF9-dHDL and GF9-sHDL, respectively) (Fig. 8). When delivered at this dose in free form, GF9 did not affect lethality as compared with vehicle-treated control mice (Fig. 8). In contrast, when delivered using macrophage-specific HDL particles, GF9 significantly prolonged survival of endotoxemic mice as compared to control mice treated with nanoparticles containing no GF9 (Fig. 8). Interestingly, GF9 delivered using spherical nanoparticles provides less effective but longer-lasting protection as compared to GF9 delivered using discoidal nanoparticles (Fig. 8), which may result from the longer half-life of GF9-sHDL as compared with GF9-dHDL. In a subset of experiments, the time of administration relative to LPS challenge was varied from 1 h before to 3 h after LPS challenge. The ability of 5 mg/kg GF9-dHDL and GF9-sHDL treatment to prolong survival in endotoxemic mice was found to depend on the time of injection. Decreased protection against lethal LPS-induced peritonitis was found to correspond with later times of administration – 1, 2, and 3 h after LPS challenge (data not shown), which is consistent with the data published for other TREM-1 inhibitors [13, 21].

Figure 8.

The TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 incorporated into macrophage-targeted HDL that contain oxidized apo A-I prolongs survival of mice with LPS-induced septic shock. (A) C57BL/6 mice (n=10) were intraperitoneally administered with vehicle (HDL containing no GF9) or the indicated doses of GF9, GF9-dHDL, and GF9-sHDL 1 h before LPS administration (30 mg/kg). Survival curves during the 40-h (A) and 7-d (B) periods after LPS injection are illustrated. Expected apparent half-lifes of agents in circulation are shown in the inset (B). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. **, P = 0.001 to 0.01 as compared with vehicle-treated animals. Abbreviations: apo, apolipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoproteins; dHDL and sHDL, discoidal and spherical HDL, respectively; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

In summary, together our findings demonstrate that similar to other TREM-1 inhibitors reported to date, the TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide that employs novel, ligand-independent mechanisms of TREM-1 inhibition, is capable of protecting mice against LPS-induced endotoxic shock. Similar to its antitumor effect discussed above, the ability of GF9 in both free and HDL-bound form to prolong survival in endotoxemic mice suggests that this peptide can access its target site of action from either outside or inside the cell. Incorporation of GF9 into synthetic HDL-like particles substantially reduces the effective dosage of the peptide and prolongs its protective ability, which may result from its targeted delivery to TREM-1-expressing macrophages and the prolonged circulatory half-life.

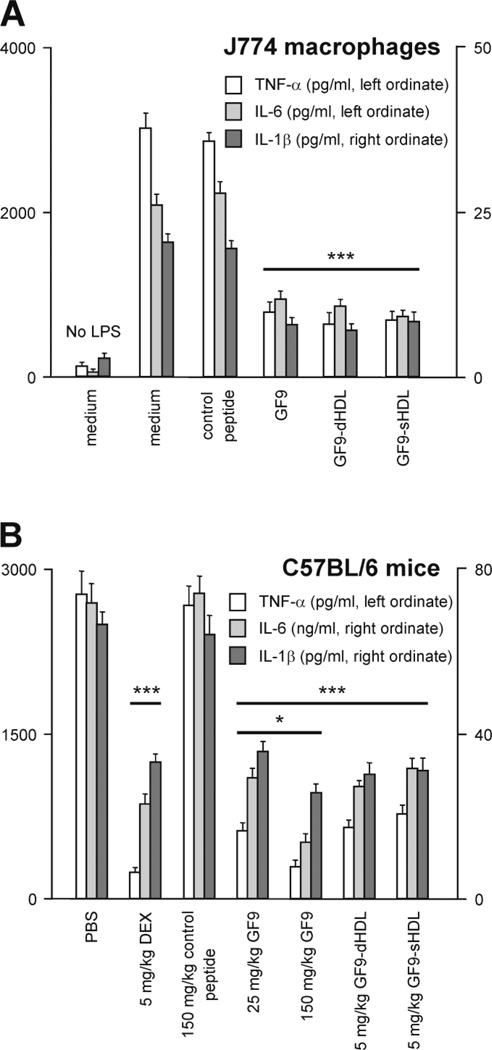

3.5. Effect of GF9 on cytokine production in LPS-stimulated macrophages and septic mice

TREM-1 activation is known to synergize the action of endotoxin and amplify the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [13, 21]. We therefore investigated whether TREM-1 inhibition using GF9 in either free or HDL-bound form affects the production of these cytokines in vitro and in vivo by using LPS-stimulated macrophages or evaluating the inflammatory cytokine response to endotoxin in mice (Fig. 9). In comparison to the J774 macrophages treated with LPS only, cells treated with 50 ng/ml GF9 in free and HDL-bound forms showed a marked reduction in secreted TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels in response to LPS, while the control peptide GF9-G did not affect LPS-induced cytokine production by macrophages (Fig. 9A). To determine the effect of GF9 on LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine levels in vivo, naïve C57BL/6 mice were i.p. injected with 30 mg/kg LPS from E. coli 055:B5 1 h after i.p. administration of PBS, the indicated doses of DEX, control peptide GF9-G or TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in either free or HDL-bound form. Then, serum cytokine levels were measured 90 min after LPS challenge. When delivered in its free form 1 h before LPS challenge, GF9 significantly inhibited LPS-induced stimulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production in a specific and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 9B). Incorporation of GF9 into macrophage-targeted HDL-like synthetic nanoparticles reduces the effective dosage of the peptide, while no differences were observed between GF9-dHDL and GF9-sHDL at the same dose (Fig. 9B). Together, these findings indicate that TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in either free or HDL-bound form specifically silences the inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Our data also suggest that the peptide can access its target site of action from both outside and inside the cell.

Figure 9.

The TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free and HDL-bound form inhibits cytokine production in vitro and in vivo. (A) Release of cytokines from J774 macrophages. Cells were cultured for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of LPS (1 µg/ml) in combination with 50 ng/ml control peptide or GF9 peptide in free and HDL-bound form. After incubation, culture medium samples were subjected to TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β determination by the appropriate ELISA kits. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001 as compared with medium-treated LPS-challenged cells. (B) Analysis of serum cytokine levels in mice during LPS-induced endotoxemia. Mice (n = 10) were treated with PBS or the indicated doses of dexamethasone (DEX), control peptide or GF9 peptide in free and HDL-bound form 1 h before LPS administration (30 mg/kg). Blood samples were obtained at 90 min post LPS challenge, and serum was screened for levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β using the appropriate ELISA kits. *, P = 0.01 to 0.05 as compared with animals treated with 25 mg/kg GF9; ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001 as compared with PBS-treated animals. Abbreviations: ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HDL, high density lipoproteins; dHDL and sHDL, discoidal and spherical HDL, respectively; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1.

4. Discussion

First reported in 2000 [43], TREM-1 amplifies the inflammatory response and plays a role in innate and adaptive immune responses [17, 44–46]. This receptor is upregulated under a variety of inflammatory conditions [16, 47] and represents a promising therapeutic target for inflammation-associated disorders. Recent research revealed that blockade of the TREM-1 signaling pathway could be a new approach to treat such seemingly unrelated diseases as cancer, sepsis, rheumatoid arthritis and other serious disorders with unmet clinical need (Table 1). To date, the most commonly used TREM-1 inhibitors include a TREM-1 decoy receptor and the TREM-1 antagonist LP-17 (Table 1), both of which block the binding of ligand(s) to TREM-1 (Fig. 1A). However, the unknown identity and occurrence of the natural TREM-1 ligand(s) combined with our lack of understanding as to how TREM-1 signals are impairing our understanding of TREM-1 biology and consequently hindering the development of new therapies that target TREM-1.

TABLE 1.

TREM-1 inhibitors and their effect on inflammation-associated disorders.

| Disorder/Condition | Animals | TREM-1 inhibitor | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC | Mice | SCHOOL peptide | Inhibits tumor growth | This study |

| Colon cancer | Mice | LP-17 | Attenuates inflammation and tumor within the colon | [24] |

| Sepsis | Mice | SCHOOL peptide | Reduces levels of TNF-α, IL- 6, and IL-1β and improves survival | This study |

| Sepsis | Mice | TREM-1/Ig | Reduces levels of TNF-α and IL-1β and improves survival | [13] |

| Sepsis | Mice | TREM-1 siRNA duplexes | Reduces levels of TNF-α, IL- 6, and IL-1β and improves survival | [21] |

| Sepsis | Mice | LP-17 | Improves survival | [41] |

| Sepsis | Mice | TREM-1/Ig | Reduces levels of TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-1β and improves survival of mice with Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced peritonitis | [22] |

| Sepsis | Mice | TREM-1/Ig | Reduces levels of inflammatory cytokines and improves survival of mice with Streptococcus pyogenes- induced severe sepsis | [61] |

| Colitis | Mice | LP-17 | Reduces levels of TNF-α, IL- 6, IL-8, MCP-1, and IL-1β and attenuates clinical course of colitis | [16] |

| Pancreatitis-associated IBD | Rats | LP-17 | Mitigates the inflammatory response associated with severe acute pancreatitis and provides therapeutic protection from intestinal mucosal damage | [69] |

| Hemorrhagic shock | Rats | LP-17 | Reduces levels of TNF-α and IL-6 and improves survival | [23] |

| Mesenteric ischemia- reperfusion | Rats | LP-17 | Attenuates remote inflammation, cardiovascular compromise, and intestinal barrier dysfunction | [70] |

| Empyema | Rats | LP-17 | Attenuates pleural and systemic inflammatory responses and promotes survival | [14] |

| Arthritis | Mice | TREM-1/Ig, LP-17 | Ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis | [15] |

Abbreviations: GF9, TREM-1-specific SCHOOL peptide; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL, interleukin; LP-17, antagonistic TREM-1 peptide; MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCHOOL, signaling chain homooligomerization; siRNA, small interfering RNA; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TREM-1, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1; TREM-1/Ig, fusion protein containing TREM-1 extracellular domain and human immunoglobulin (Ig) Fc portion.

The extracellular recognition and the intracellular signaling modules of TREM-1 are located on two separate receptor subunits, TREM-1 and DAP-12, which are noncovalently associated via a positively charged lysine and a negatively charged aspartic acid in the transmembrane domains of TREM-1 and DAP-12, respectively (Fig. 1A). Thus, TREM-1 belongs to the family of receptors called the multichain immune recognition receptor (MIRR) family [48]. Based on a novel, previously unreported phenomenon – specific homooligomerization of intrinsically disordered MIRR signaling subunits [49–50], we developed a new model for MIRR signaling, called the SCHOOL model [48]. The model reveals new therapeutic targets including transmembrane interactions between the MIRR recognition and signaling subunits [25]. Furthermore, the SCHOOL model explains for the first time the molecular mechanisms of ligand-independent inhibition of another MIRR, the T cell receptor (TCR), by using a short synthetic peptide (SCHOOL peptide) corresponding to the transmembrane sequence of TCR-α chain [51]. As demonstrated in cell, animal, and preliminary human studies, inhibitory TCR SCHOOL peptides can represent a novel approach to treat TCR-mediated disorders [52]. Another exemplary member of the MIRR family is glycoprotein VI (GPVI). Selective inhibition of this central platelet collagen receptor may reduce thrombosis without affecting hemostatic plug formation. Recently, we have successfully used the SCHOOL model to develop a novel, ligand-independent peptide inhibitor of GPVI and demonstrated its antithrombotic activity [53]. Intriguingly, as revealed recently [54–56], different viruses use SCHOOL-like mechanisms to modulate the host immune response mediated by TCR and other MIRRs. Viruses represent years of evolution and the efficiency and optimization that come along with it suggesting that this ligand-independent strategy of receptor inhibition can be effectively used for therapeutic purposes.

In this study, we used the SCHOOL model to design a ligand-independent inhibitor of TREM-1, a 9-mer synthetic peptide GF9 that corresponds to the transmembrane sequence of TREM- 1, and tested this peptide using J774 macrophages in vitro and in animal models of NSCLC and sepsis. We have chosen to evaluate GF9 in these diseases because of the following considerations: 1) TREM-1 expression on TAMs is associated with cancer recurrence and poor survival of patients with NSCLC [18], 2) TREM-1 expression on macrophages is markedly increased in patients with sepsis [19–20], 3) blockade of TREM-1 protects mice against septic shock [13], and 4) there is an urgent and unmet clinical need for novel therapies for NSCLC and sepsis. A peptide GF9-G, with lysine replaced by glycine, was used as a control peptide in this study. According to the SCHOOL model [48], this peptide cannot compete with TREM-1 for binding to DAP-12, and thus cannot inhibit TREM-1 signaling.

Considering the short circulatory half-life of peptides in vivowhich is typically only a few minutes [38], we tested whether this peptide can be incorporated into discoidal and spherical nanoparticles that mimic human HDL, a group of native lipoproteins that transport cholesterol from the peripheral tissues to the liver and can be readily reconstituted in vitro from lipids and apolipoproteins [57]. Due to the half-life of native discoidal and spherical HDL in normal subjects being 12-20 hrs and 3-5 days, respectively [39–40], these particles represent a promising versatile delivery platform for peptide therapeutics. Synthetic (reconstituted) HDL have several competitive advantages as compared with other delivery platforms: 1) apo A-I, the major HDL protein, is an endogenous protein and does not trigger immunoreactions, 2) the small size (8-12 nm) allows HDL to enter and accumulate in tissue and organ areas of interest, and 3) a variety of drugs and imaging agents can be incorporated into this platform [29, 58–59].

Further, TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 targets interactions between TREM-1 and its signaling partner, DAP-12, within the cell membrane (Fig. 1A). Thus, this peptide can access its target site of action from both outside and inside the cell, which makes it possible to use macrophage uptake as a means to target GF9 into TREM-1-expressing macrophages. Targeting of the GF9- containing synthetic HDL particles to macrophages was achieved by using a naturally occurring oxidative modification of the major HDL protein, apo A-I (Fig. 1B) that represents a physiological way of delivering the incorporated drugs and/or imaging agents to macrophages in vivo. Previously, we demonstrated that this modification converts HDL into a substrate for macrophages and can be used for targeted delivery of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents to macrophages in vitro and in vivo [31]. In the present study, in order to confirm targeted delivery of the encapsulated TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 to macrophages, synthetic discoidal and spherical HDL particles containing either oxidized or unmodified apo A-I were successfully loaded with GF9 and subsequently purified and characterized using a variety of biophysical procedures. For comparative macrophage uptake studies in vitro, GF9-containing HDL particles were also loaded with a rhodamine B-labeled lipid. After incubating the J774 macrophages with fluorescently labeled GF9- HDL for 4, 12, and 24 h, particles with oxidized apo A-I showed substantially higher macrophage uptake relative to its unmodified counterpart as detected by rhodamine B fluorescence intensities of cell lysates (Fig. 3). In this work, we used high-purity apo A-I preparations isolated from human serum and characterized these preparations using a variety of techniques including analytical RP-HPLC, mass spectrometry (MS), and SDS-PAGE as described previously [26–27, 30]. While we observed some macrophage uptake of HDL particles containing unmodified protein in vitro (Fig. 3), this may be explained by the activity of myeloperoxidase (MPO), which is secreted by macrophages and neutrophils and may cause oxidative damage to apo A-I and consequently target these particles to macrophages [60].

With respect to therapeutics, human apo A-I is a large protein, which is purified from human plasma. Thus, in addition to the immense monetary cost in purification, further development of apo A-I-containing therapeutic agents would require a number of safety precautions followed by a complicated transition into clinical practice. Previously, we showed that synthetic 22-mer peptides that correspond to apo A-I helixes 4 and 6 containing Met-112 and Met-148, respectively, can be used in place of native apo A-I to assist in the self-assembly of the fully functional HDL particle containing the MRI imaging probe [31]. Importantly, we demonstrated that when these 22-mer peptides are oxidized, specific targeting to macrophages is observed [31]. In this study, we show that upon oxidation, these apo A-I peptides can be successfully used for the targeted delivery of the GF9-containing discoidal and spherical HDL particles to macrophages.

As mentioned above, TREM-1 has been recently found on TAMs in the microenvironment of malignant pleural effusions and primary lung tumors [18]. In the clinical setting, TREM-1 expression on TAMs is associated with cancer recurrence and poor survival of patients [18]. Although inhibition of TREM-1 by shRNA in macrophages has been shown to suppress cancer cell invasion in vitro [18], the question still remains as to whether blockade of TREM-1 leads to tumor growth inhibition in vivo. To support the "cause-effect relationship" between TREM-1 activity and tumor growth, we are demonstrating preclinical antitumor efficacy of a novel mechanism-based peptide inhibitor of TREM-1 using NSCLC cell lines. As expected, TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in free and HDL-bound form showed dose-dependent antitumor effects in A549 and H292 xenografts grown in nude mice (Figs. 4, 5, and 6). These findings are consistent with a recently published report that indicates that inhibition of TREM-1 using an antagonist LP-17 ameliorates the development of inflammation and tumor within the colon [24]. As shown in the current study, incorporation of GF9 into discoidal and spherical HDL-like nanoparticles reduces the effective dosage of the peptide: while GF9 in free form administered twice a week at a dose of 5 mg/kg does not exhibit antitumor activity in either xenograft model of NSCLC (not shown), GF9-dHDL (administered twice a week) and GF9-sHDL (administered once a week) suppress tumor growth with the % T/C values of 40 and 41% (H292 xenografts) and 29 and 27% (A549 xenografts), respectively. Importantly, GF9-dHDL administered at a dose of 5 mg/kg of GF9 once a week does not affect tumor growth, which may be explained by the shorter circulatory half-life of discoidal HDL as compared to spherical HDL. This is also supported by the observed antitumor effect of 32% T/C of an all D-amino acid analogue of GF9 (GF9-d) administered in free form at a dose of 5 mg/kg twice a week. Collectively, our findings complement recently published data on antitumor activity of a TREM-1 antagonist LP-17 observed in a mouse model of colitis-induced colon cancer [24]. Thus, one can suggest that targeting TREM-1 using novel mechanism-based peptide inhibitors may represent a new therapeutic strategy for a variety of inflammation-associated types of cancer. Examples are pancreatic, breast, prostate, and ovarian cancers.

In a mouse model of LPS-induced septic shock, stimulation of TREM-1 using an agonist anti-TREM-1 monoclonal antibody increases the mortality rate from 50 to 100% [41]. In contrast, blockade of TREM-1 modulates the inflammatory response and improves survival in this and other mouse models of sepsis including CLP, and E. coli-, S. pyogenes-, or P. aeruginosa-induced peritonitis models [13, 21–22, 41–42, 61]. In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that a novel and first-in-class ligand-independent TREM-1 inhibitory peptide GF9 can be used to silence the TREM signaling pathway and prolong survival in mice with LPS-induced septic shock. This effect is specific and dose-dependent: while administration of GF9 in free form at a dose of 5 mg/kg does not show a protective effect against LPS-induced endotoxic shock, the higher dose of GF9 (but not GF9-G) prolongs survival of septic mice. The use of the HDL-bound form of GF9 reduces the effective dosage of the peptide. Interestingly, when injected at the same dose of 5 mg/kg, GF9-sHDL provide slightly less effective but longer-lasting protection as compared with GF9-dHDL (Fig. 8), which may result from the longer half-life of spherical HDL in circulation.

At the molecular level, activation of TREM-1 amplifies the production of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [13, 21]. In line with this, we found in the present study that TREM-1 silencing using GF9 in either free or HDL-bound form is associated with a substantial reduction in the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in LPS-stimulated macrophages in vitro and during LPS-induced sepsis in mice (Fig. 9). While the observed suppression of proinflammatory cytokine production provides a reasonable molecular explanation for the ability of GF9 to prolong survival in septic mice, the molecular mechanisms underlying its antitumor effect are not clear. On the other hand, TREM-1 activation induces M-CSF [17], the growth factor that regulates activation, growth and differentiation of macrophages including TAMs [6]. Studies in M-CSF-deficient mice revealed a role for M-CSF in promoting tumor growth and tumor progression to metastasis [62]. Suppression of M-CSF has been shown to inhibit the growth of human tumor xenografts in mice, prolong mouse survival and decrease macrophage infiltration and angiogenesis [63]. Thus, the antitumor effect of TREM-1 inhibitors observed for TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide GF9 in the present study and for a TREM-1 antagonist LP-17[24] may be provided at least in part by reduction of the TREM-1-mediated production of M-CSF.

Surprisingly, we found that the use of a very high dose of GF9 in free form (150 mg/kg) does not show antitumor activity in either xenograft mouse model of NSCLC (Fig. 4). In septic mice, the administration of 150 mg/kg GF9 peptide in free form does not prolong survival, but in fact contributes to earlier death as compared with control animals treated with vehicle only (Fig. 7A). This effect is specific as the control peptide GF9-G administered at a dose of 150 mg/kg does not affect survival in septic mice. Further, no weight loss was observed in healthy mice treated with increasing doses of GF9 up to 300 mg/kg, indicating that this peptide is non-toxic and well-tolerated (Fig. 7B). Although the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the observed phenomena are not completely understood, collectively, these data lend support to the idea that excessive immunomodulation may impair the balance between the beneficial and the detrimental effects of cytokines. For example, anti-TNF-α therapy use in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a double risk of a potentially life-threatening complication known as septic arthritis [64], highlighting an important role that TNF-α plays in the clearance of infection. In this context, the deleterious effect of a high dose of GF9 that we observed in septic mice and failure of most anti-cytokines and antiinflammatory agents, including IL-1 receptors and polyclonal (CytoFab) and monoclonal anti-TNF- α antibodies, to significantly reduce mortality in septic shock [65–68] may be mechanistically similar. However, further studies are needed before a clear conclusion can be reached.

In summary, the present study is the first to demonstrate that a novel mechanism-based nontoxic TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide in free and nanoparticle-encapsulated form: 1) specifically silences the TREM-1 signaling pathway and modulates TREM-1-mediated production of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in vitro and in vivo2) exhibits in vivo antitumor activity and reduces tumor growth in the H292 and A549 xenograft mouse models of lung cancer, and 3) prolongs survival in a mouse model of LPS-induced sepsis. We also show that incorporation of this inhibitory peptide into macrophage-targeted reconstituted HDL reduces the effective dosage of the peptide and improves its half-life. Importantly, native apo A-I in these HDL-like particles can be functionally replaced by synthetic peptides that correspond to amphipathic apo A-I helixes 4 and 6, which contain methionine residues Met-112 and Met-148. Our results strongly encourage the further development of these TREM-1 SCHOOL peptide-based formulations with broad application in oncology, sepsis, and other inflammation-associated diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, colitis and IBD, where blockade of TREM-1 has important therapeutic value. When considered in conjunction with our previous study [31], this work supports the versatility and multifunctionality of the HDL nanoplatform for targeted delivery to macrophages of not only imaging probes, but also drugs, thus enabling theranostic applications.

HIGHLIGHTS.

The TREM-1213-221 peptide (GF9) reduces production of inflammatory cytokines in vitro and in vivo

GF9 reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer

GF9 prolongs survival in mice with lipopolysaccharide-induced septic shock

Synthetic HDL can be used to deliver GF9 to macrophages

Incorporation of GF9 into HDL nanoparticles decreases the effective dosage of the peptide

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to VIVOPATH for animal experiments. We also owe a debt of gratitude to Walter Lunsmann, Dr. Philip Lambert, and Margaret Sposato, who did an excellent job conducting mouse studies, for their important expertise, experience, and skills and for numerous valuable discussions. Transmission electron microscopy was performed at the Core Electron Microscopy Facility of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. We thank Dr. Gregory Hendricks for helpful discussions of results. This work was partially supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) / U.S. Army Research Office [Contract No. W911NF-12-C-0003] and the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Project Grant No. R43CA167865].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Felip E, Santarpia M, Rosell R. Emerging drugs for non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2007;12:449–460. doi: 10.1517/14728214.12.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) as major players of the cancer-related inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1065–1073. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih J-Y, Yuan A, Chen JJ-W, Yang P-C. Tumor-Associated Macrophage: Its Role in Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. J Cancer Mol. 2006;2:101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welsh TJ, Green RH, Richardson D, Waller DA, O'Byrne KJ, Bradding P. Macrophage and mast-cell invasion of tumor cell islets confers a marked survival advantage in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8959–8967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elgert KD, Alleva DG, Mullins DW. Tumor-induced immune dysfunction: the macrophage connection. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:275–290. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaminska J, Kowalska M, Kotowicz B, Fuksiewicz M, Glogowski M, Wojcik E, et al. Pretreatment serum levels of cytokines and cytokine receptors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer, and correlations with clinicopathological features and prognosis. M-CSF - an independent prognostic factor. Oncology. 2006;70:115–125. doi: 10.1159/000093002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–891. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Immune dysfunction in murine polymicrobial sepsis: mediators, macrophages, lymphocytes and apoptosis. Shock. 1996;6(Suppl 1):S27–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oren H, Duman N, Abacioglu H, Ozkan H, Irken G. Association between serum macrophage colony-stimulating factor levels and monocyte and thrombocyte counts in healthy, hypoxic, and septic term neonates. Pediatrics. 2001;108:329–332. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gogos CA, Drosou E, Bassaris HP, Skoutelis A. Pro-versus anti-inflammatory cytokine profile in patients with severe sepsis: a marker for prognosis and future therapeutic options. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:176–180. doi: 10.1086/315214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchon A, Facchetti F, Weigand MA, Colonna M. TREM-1 amplifies inflammation and is a crucial mediator of septic shock. Nature. 2001;410:1103–1107. doi: 10.1038/35074114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo L, Zhou Q, Chen XJ, Qin SM, Ma WL, Shi HZ. Effects of the TREM-1 pathway modulation during empyema in rats. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:1561–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami Y, Akahoshi T, Aoki N, Toyomoto M, Miyasaka N, Kohsaka H. Intervention of an inflammation amplifier, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1, for treatment of autoimmune arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1615–1623. doi: 10.1002/art.24554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schenk M, Bouchon A, Seibold F, Mueller C. TREM-1--expressing intestinal macrophages crucially amplify chronic inflammation in experimental colitis and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3097–3106. doi: 10.1172/JCI30602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dower K, Ellis DK, Saraf K, Jelinsky SA, Lin LL. Innate immune responses to TREM-1 activation: overlap, divergence, and positive and negative cross-talk with bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2008;180:3520–3534. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho CC, Liao WY, Wang CY, Lu YH, Huang HY, Chen HY, et al. TREM-1 expression in tumor-associated macrophages and clinical outcome in lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:763–770. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-641OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Bremen T, Dromann D, Luitjens K, Dodt C, Dalhoff K, Goldmann T, et al. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 (Trem-1) on blood neutrophils is associated with cytokine inducibility in human E. coli sepsis. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:24–31. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibot S. Clinical review: role of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 during sepsis. Crit Care. 2005;9:485–489. doi: 10.1186/cc3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibot S, Massin F, Marcou M, Taylor V, Stidwill R, Wilson P, et al. TREM-1 promotes survival during septic shock in mice. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:456–466. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang F, Liu S, Wu S, Zhu Q, Ou G, Liu C, et al. Blocking TREM-1 signaling prolongs survival of mice with Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced sepsis. Cell Immunol. 2012;272:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibot S, Massin F, Alauzet C, Derive M, Montemont C, Collin S, et al. Effects of the TREM 1 pathway modulation during hemorrhagic shock in rats. Shock. 2009;32:633–637. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a53842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou J, Chai F, Lu G, Hang G, Chen C, Chen X, et al. TREM-1 inhibition attenuates inflammation and tumor within the colon. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigalov AB. Immune cell signaling: a novel mechanistic model reveals new therapeutic targets. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sigalov A, Alexandrovich O, Strizevskaya E. Large-scale isolation and purification of human apolipoproteins A-I and A-II. J Chromatogr. 1991;537:464–468. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)88920-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigalov AB, Stern LJ. Enzymatic repair of oxidative damage to human apolipoprotein A-I. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oda MN, Hargreaves PL, Beckstead JA, Redmond KA, van Antwerpen R, Ryan RO. Reconstituted high density lipoprotein enriched with the polyene antibiotic amphotericin B. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:260–267. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D500033-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sigalov AB, Stern LJ. Oxidation of methionine residues affects the structure and stability of apolipoprotein A-I in reconstituted high density lipoprotein particles. Chem Phys Lipids. 2001;113:133–146. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(01)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sigalov AB. Nature-inspired nanoformulations for contrast-enhanced in vivo MR imaging of macrophages. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1587. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConathy WJ, Nair MP, Paranjape S, Mooberry L, Lacko AG. Evaluation of synthetic/reconstituted high-density lipoproteins as delivery vehicles for paclitaxel. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:183–188. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f1da86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markwell MA, Haas SM, Bieber LL, Tolbert NE. A modification of the Lowry procedure to simplify protein determination in membrane and lipoprotein samples. Anal Biochem. 1978;87:206–210. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Veldhoven PP, Mannaerts GP. Inorganic and organic phosphate measurements in the nanomolar range. Anal Biochem. 1987;161:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90649-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson JI, Decker S, Zaharevitz D, Rubinstein LV, Venditti JM, Schepartz S, et al. Relationships between drug activity in NCI preclinical in vitro and in vivo models and early clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1424–1431. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen W, Vucic E, Leupold E, Mulder WJ, Cormode DP, Briley-Saebo KC, et al. Incorporation of an apoE-derived lipopeptide in high-density lipoprotein MRI contrast agents for enhanced imaging of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2008;3:233–242. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta S, Jain A, Chakraborty M, Sahni JK, Ali J, Dang S. Oral delivery of therapeutic proteins and peptides: a review on recent developments. Drug Deliv. 2013;20:237–246. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2013.819611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scanu A, Hughes WL. Further characterization of the human serum D 1.063-1.21, alpha-lipoprotein. J Clin Invest. 1962;41:1681–1689. doi: 10.1172/JCI104625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furman RH, Sanbar SS, Alaupovic P, Bradford RH, Howard RP. Studies of the Metabolism of Radioiodinated Human Serum Alpha Lipoprotein in Normal and Hyperlipidemic Subjects. J Lab Clin Med. 1964;63:193–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gibot S, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Bene MC, Bollaert PE, Lozniewski A, Mory F, et al. A soluble form of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 modulates the inflammatory response in murine sepsis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1419–1426. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibot S, Buonsanti C, Massin F, Romano M, Kolopp-Sarda MN, Benigni F, et al. Modulation of the triggering receptor expressed on the myeloid cell type 1 pathway in murine septic shock. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2823-2830.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bouchon A, Dietrich J, Colonna M. Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:4991–4995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.4991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bleharski JR, Kiessler V, Buonsanti C, Sieling PA, Stenger S, Colonna M, et al. A role for triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 in host defense during the early-induced and adaptive phases of the immune response. J Immunol. 2003;170:3812–3818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tessarz AS, Cerwenka A. The TREM-1/DAP12 pathway. Immunol Lett. 2008;116:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klesney-Tait J, Turnbull IR, Colonna M. The TREM receptor family and signal integration. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1266–1273. doi: 10.1038/ni1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang DY, Qin RY, Liu ZR, Gupta MK, Chang Q. Expression of TREM-1 mRNA in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2744–2746. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i18.2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sigalov AB. Multichain immune recognition receptor signaling: different players, same game? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigalov A, Aivazian D, Stern L. Homooligomerization of the cytoplasmic domain of the T cell receptor ζ chain and of other proteins containing the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2049–2061. doi: 10.1021/bi035900h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sigalov AB. Uncoupled binding and folding of immune signaling-related intrinsically disordered proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;106:525–536. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amon MA, Ali M, Bender V, Chan YN, Toth I, Manolios N. Lipidation and glycosylation of a T cell antigen receptor (TCR) transmembrane hydrophobic peptide dramatically enhances in vitro and in vivo function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Enk AH, Knop J. T cell receptor mimic peptides and their potential application in T-cell-mediated disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2000;123:275–281. doi: 10.1159/000053639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sigalov AB. Novel mechanistic concept of platelet inhibition. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:677–692. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quintana FJ, Gerber D, Kent SC, Cohen IR, Shai Y. HIV-1 fusion peptide targets the TCR and inhibits antigen-specific T cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2149–2158. doi: 10.1172/JCI23956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sigalov AB. Novel mechanistic insights into viral modulation of immune receptor signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000404. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matalon E, Faingold O, Eisenstein M, Shai Y, Goldfarb D. The topology, in model membranes, of the core peptide derived from the T-cell receptor transmembrane domain. Chembiochem. 2013;14:1867–1875. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jonas A. Reconstitution of high-density lipoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 1986;128:553–582. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)28092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lacko AG, Nair M, Prokai L, McConathy WJ. Prospects and challenges of the development of lipoprotein-based formulations for anti-cancer drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:665–675. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skajaa T, Cormode DP, Falk E, Mulder WJ, Fisher EA, Fayad ZA. High-density lipoprotein-based contrast agents for multimodal imaging of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:169–176. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bergt C, Marsche G, Panzenboeck U, Heinecke JW, Malle E, Sattler W. Human neutrophils employ the myeloperoxidase/hydrogen peroxide/chloride system to oxidatively damage apolipoprotein A-I. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:3523–3531. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]