Abstract

Detection of human cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection internationally is a global public health concern. Rigorous risk assessment is particularly challenging in a context where surveillance may be subject to under-ascertainment and a selection bias towards more severe cases. We would like to assess whether the virus is capable of causing widespread human epidemics, and whether self-sustaining transmission is already under way. Here we review possible transmission scenarios for MERS-CoV and their implications for risk assessment and control. We discuss how existing data, future investigations and analyses may help in reducing uncertainty and refining the public health risk assessment and present analytical approaches that allow robust assessment of epidemiological characteristics, even from partial and biased surveillance data. Finally, we urge that adequate data be collected on future cases to permit rigorous assessment of the transmission characteristics and severity of MERS-CoV, and the public health threat it may pose. Going beyond minimal case reporting, open international collaboration, under the guidance of the World Health Organization and the International Health Regulations, will impact on how this potential epidemic unfolds and prospects for control.

As of 30 May 2013, 50 laboratory-confirmed cases of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection have occurred worldwide [1]. An apparently high case-fatality ratio (60%; 30 deaths as of 30 May 2013 [1]) and growing evidence that human-to-human transmission is occurring [2] make MERS-CoV a threat to global health. The current situation has already been compared to the early stages of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2003 [3,4].

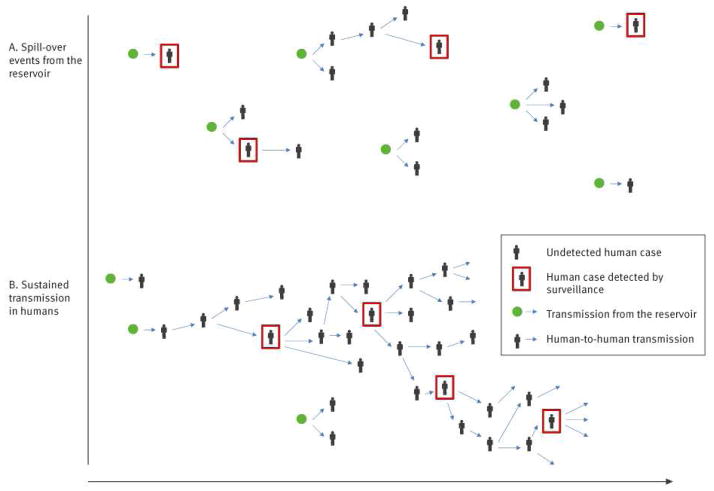

No animal reservoir has yet been identified for MERS-CoV, and yet human cases, mostly severe, have been detected over a wide geographical area in the Middle East and Europe. If most human cases to date have arisen from animal exposure, this implies a large but as yet uncharacterised zoonotic epidemic is under way in animal species to which humans have frequent exposure (Figure 1A). In this scenario, we might expect relatively small numbers of human cases overall, though with the limited surveillance data available to date, we cannot rule out the possibility that substantial numbers of human cases, with milder disease, have gone undetected.

Figure 1.

Two illustrative scenarios for transmission of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV)

A. Few human-to-human infection events have occurred and observed clusters have arisen from separate spill-over events (i.e. introductions from the animal reservoir into human populations).

B. Many undetected human-to human transmission events have occurred and the epidemic is already self-sustaining.

Even if most human cases to date have been infected through zoonotic exposure, is it possible that MERS-CoV already has the potential to support sustained human-to-human transmission but has by chance so far failed to do so?

Alternatively, how feasible is it that most of the severe MERS-CoV cases detected to date were in fact infected via human-to-human transmission and that the epidemic is already self-sustaining in human populations (Figure 1B)? Under this transmission scenario, substantial numbers of human infections may have already occurred, with only a small proportion of them being detected. But is it feasible that such an epidemic would not have been recognised?

Each of these scenarios has very different implications for the assessment of severity, relevance of reservoir-targeted strategies and potential impact of MERS-CoV globally. Although it may not be possible to completely rule out any of the scenarios with the data currently available, it is timely to consider the priorities for data collection and analysis as cases accrue, so as to best be able to reduce uncertainty and refine the public health risk assessment.

Transmission scenarios for an emerging infection

The human-to-human transmissibility (and thus epidemic potential) of an emerging pathogen is quantified by the (effective) reproduction number, R, the average number of secondary infections caused by an index human infection. Depending on the value of R, different transmission scenarios are possible, as described below.

Scenario 1: subcritical outbreaks (R<1)

If R<1, a single spill-over event from a reservoir into human populations may generate a cluster of cases via human-to-human transmission, but cannot generate a disseminated, self-sustaining epidemic in humans. The number of human infections expected under this scenario is roughly proportional to the number of zoonotic introductions of the virus into the human population, with a multiplier, 1/(1–R), that increases with R (twofold if R=0.5, but 10-fold if R=0.9).

In this scenario, human infections can be mitigated by controlling the epidemic in the reservoir and/or preventing human exposure to the reservoir. Examples of this scenario are A(H5N1) and A(H7N9) avian influenzas.

Scenario 2: supercritical outbreaks (R>1 but epidemic has not yet become self-sustaining in human populations)

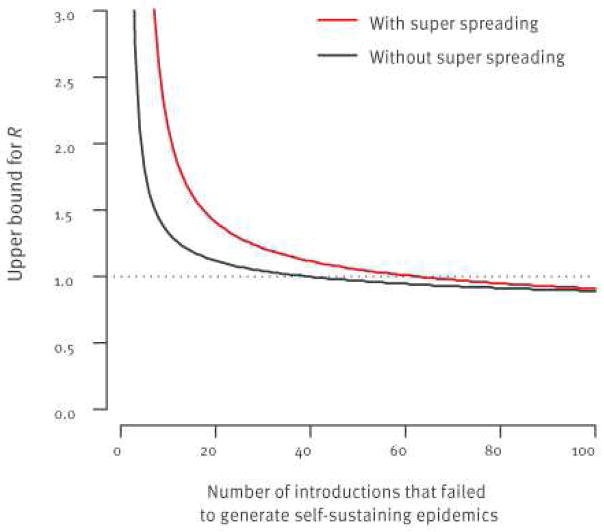

If R>1, a self-sustaining epidemic in humans is possible but emergence following introduction is a chance event: many chains of transmission may extinguish themselves by chance, especially if R is close to 1. In the case of SARS, for example, where ‘super-spreading’ events played an important role in transmission (i.e. a small proportion of cases were responsible for a large proportion of onward transmission) it has been estimated that there was only a 24% probability that a single introduction would generate a self-sustaining epidemic [5] (following [5], we technically define ‘super-spreading’ events by an over-dispersion parameter k=0.16; the absence of super-spreading events is defined by k=0.5). This is because if the first cases were not part of a super-spreading event, they would be unlikely to generate further cases. However, in this scenario, a self-sustaining epidemic is eventually inevitable if zoonotic introductions into the human population continue (Figure 2). As with the subcritical scenario (R<1), reducing infections from the reservoir is critical to reducing the public health risk.

Figure 2.

Probability that the epidemic of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection has become self-sustaining in humans after n introductions from the reservoir if R>1

R: reproduction number.

This probability depends not only on R but also on the presence of super- spreading events (SSE) (without SSE: plain line; with SSE; dotted line). Values R=3 and R=1.2 were selected for illustrative purposes.

Scenario 3: self-sustaining epidemic (R>1)

If R>1 and the epidemic has become self-sustaining in humans, the number of human cases is expected to grow exponentially over time. The rate of growth increases with R, but decreases with the mean generation time (GT), the time lag from infection of an index case to infection of those they infect. For example, for an eight-day GT – similar to that of SARS – once self-sustaining, the number of human cases is expected to double about every week if R=2, but only about every month if R=1.2. Although chance effects may mask exponential growth early in the epidemic, a clear signal of increasing incidence would be expected once the number of prevalent infections increases sufficiently [6]. If case ascertainment remains constant over time, the incidence of detected cases would be expected to track that of underlying infections, even if only a small proportion of cases are detected. Once the epidemic is self-sustaining, control of the epidemic in the reservoir would have limited impact on the epidemic in humans.

Publicly available data

As of 30 May 2013, 50 confirmed cases of MERS-CoV have been reported with symptom onset since April 2012 from Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom (UK), France and Tunisia [1,2,7–24]. There are additional probable cases from Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia [1,12,14]. Information on animal exposures is limited and the animal reservoir has not yet been identified. However, we suspect that some of the cases may have arisen from zoonotic exposure in the Arabian Peninsula. Human-to-human transmission is suspected in several familial and healthcare facility clusters in Saudi Arabia, Jordan UK and France. We understand that follow-up investigations of contacts of the confirmed MERS-CoV cases have taken place by Ministry of Health officials in affected countries, finding no evidence of additional symptomatic infection [7–10,15–19]. At this stage, it is difficult to ascertain whether other primary zoonotic or secondary human-to-human cases have been missed. Most cases have been reported as severe disease (40 of 44 with documented severity) and 30 (as of 30 May 2013) have been fatal [25]. Table 1 summarises data for each cluster.

Table 1.

Summary information per cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection, as of 4 June 2013

| Cluster ID | Country identified | Date of reporting | Date first symptom onset | Number of confirmed cases | Number of cases infected by human-to-human transmission | Number of reported probable cases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saudia Arabia | 20 Sep 2012 | 13 Jun 2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1,19] |

| 2 | Saudia Arabia | 1 Nov 2012 | 5 Oct 2012 | 3 | 0 | 1 | [1,13] |

| 3 | Saudia Arabia | 4 Nov 2012 | 9 Oct 2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [7,21] |

| 4 | Jordan | 30 Nov 2012 | 21 Mar 12 | 2 | 0 | 9 | [1,12] |

| 5 | United Kingdom | 22 Sep 2012 | 3 Sep 2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [8] |

| 6 | Germany | 1 Nov 2012 | 1 Oct 2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1,9] |

| 7 | United Kingdom | 11 Feb 2013 | 24 Jan 2013 | 3 | 2 | 0 | [1,2] |

| 8 | Saudia Arabia | 21 Feb 2013 | NR | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 9 | Saudia Arabia | 7 Mar 2013 | NR | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 10 | Saudia Arabia | 12 Mar 2013 | 24 Feb 2013 | 2 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 11 | Germany | 26 Mar 2013 | NR | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 12 | Saudia Arabia | 9 May 2013 | 6 Apr 2013 | 21 | Unknown | 0 | [20,22–24] |

| 13 | France | 9 May 2013 | 22 Apr 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1,11] |

| 14 | Saudia Arabia | 14 May 2013 | 25 Apr 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 15 | Saudia Arabia | 18 May 2013 | 28 Apr 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 16 | Tunisia | 22 May 2013 | NR | 2 | 2 | 1 | [1] |

| 17 | Saudia Arabia | 22 May 2013 | NR | 1 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| 18 | Saudia Arabia | 28 May 2013 | 12 May 2013 | 5 | Unknown | 0 | [1] |

NR: not reported.

Urgent data needs

Existing and additional data will help characterise the MERS-CoV transmission scenario. Many appeals for data have been brought forward by several experts and institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO). We support this and summarise data requirements and the studies required to collect such data are summarised in Table 2. We illustrate here how these data may be analysed and interpreted with adequate statistical techniques [26–28].

Table 2.

Assessing the transmission scenario of a zoonotic virus: data requirements, suggested investigations, parameter estimation and policy implications

| Improved knowledge |

Data requirements | Recommended study investigations |

Parameter estimation |

Policy implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of reservoir species and exposure data |

|

|

|

|

| Thorough epidemiological investigations of clusters of human casesb |

|

Epidemiological, virological and serologicala investigations of:

|

|

|

| Population-level infection datab |

|

|

|

|

Line-list data on confirmed cases

The spatio-temporal dynamics of cases may be used to ascertain whether the epidemic is self-sustaining and if so, to characterise human-to-human transmission [27–29]. It is therefore important that detailed epidemiological information is recorded for all confirmed and probable cases.

Identification of the reservoir species and exposure data

The importance of identifying animal reservoir(s) and understanding human exposure to reservoir species (e.g. direct contact, contact via contaminated food) is well recognised. Once the reservoir has been identified, any exposure of MERS-CoV human cases to that reservoir should be documented in epidemiological investigations. Currently, the uncertainty regarding reservoirs and modes of transmission mean that only five of 50 cases can reliably be classified as ‘human-to-human’ transmission, with the source of infection unclear for the remainder.

If none of the MERS-CoV cases detected by routine surveillance had exposure to the reservoir(s), this would clearly indicate that an epidemic in humans is already self-sustaining [26]. By contrast, if a substantial proportion of cases have been exposed to the reservoir(s), it may be possible to rule out the hypothesis that R≥1.

A similar analytical approach can be used to assess local levels of transmission in countries where MERS-CoV cases are imported from abroad. We can determine if there is self-sustaining transmission in a country by monitoring the proportion of cases detected by routine surveillance with a travel history to other affected countries [26].

If reservoir exposure cannot be found in spite of detailed epidemiological investigations, this may indicate that the epidemic is already self-sustaining in humans. It is therefore important that efforts to identify the reservoir are documented even if they are unsuccessful. To date, very few of the 50 cases have reported contact with animals [1].

Thorough epidemiological investigations of clusters of human cases

Thorough and systematic epidemiological investigations – including contact tracing of all household, familial, social and occupational contacts, with virological and immunological testing – permits assessment of the extent of human infection with MERS-CoV among contacts of confirmed cases [29]. In this context, virological and serological testing is important for ascertaining secondary infections.

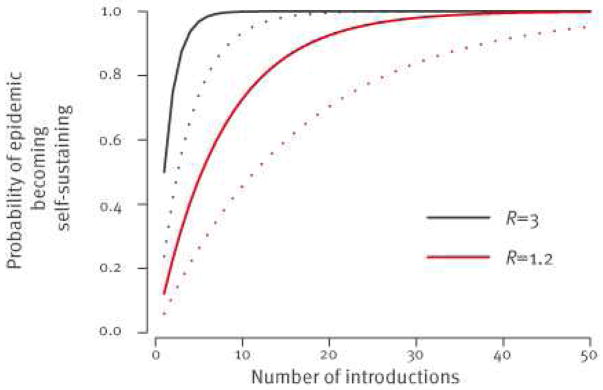

As stated above, if R>1, human-to-human transmission will eventually become self-sustaining after a sufficiently large number of virus introductions. So, if thorough cluster investigations indicate that all introductions to date have failed to generate large outbreaks, we can derive an upper bound for R (Figure 3). The distribution of cluster sizes can also be used to estimate R [30,31].

Figure 3.

Upper bound for the reproduction number R as a function of the number of introductions from the reservoir that failed to generate self-sustaining epidemics

Routine surveillance is likely to be biased towards severe cases. As a consequence, the case-fatality ratio estimated from cases detected by routine surveillance may be a substantial overestimate. Secondary cases detected during thorough epidemiological investigations of human clusters are expected to constitute a more representative sample of cases in general, meaning more reliable estimates of severity will be obtained by recording clinical outcomes in this subset of cases. Seroepidemiological studies allow for better characterisation of the spectrum of disease, and for the calculation of the proportion of asymptomatic or subclinical infections [29].

Population-level data

Once reliable serological assays are available to measure levels of antibodies to MERS-CoV, it will be important to undertake serological surveys in communities affected early to assess the prevalence of MERS-CoV infection. Should MERS-CoV cases continue to arise in those communities, a rapid follow-up study to collect paired serum samples would be highly valuable. Even a relatively small number of paired sera (about 1,000) could be used to estimate underlying infection rates and refine estimates of severity [32].

Conclusions

We have described three possible transmission scenarios for the emergence of a novel human pathogen from a suspected zoonotic reservoir, with different implications for risk assessment and control.

The most optimistic scenario is that R<1, and thus there is no immediate threat of a large-scale human epidemic. In this scenario, identifying the reservoir will inform efforts to limit human exposure. Detailed genetic investigations and estimation of R are also important for determining the selection pressure and opportunity for the virus to evolve higher human transmissibility [33].

If R>1 but by chance MERS-CoV has not yet generated a self-sustaining epidemic, the total number of animal-to-human infections must have been relatively small. This would suggest that the severe cases that have been detected are not the tip of the iceberg and that disease severity is therefore high.

The final possibility, which seems the most likely as of 4 June 2013, is that R>1 and that human-to-human transmission is already self-sustaining. If this is the case, R must still be relatively low (i.e. <2) unless transmission only began to be self-sustaining in the recent past (e.g. early 2013). In this scenario, overall human case numbers might already be relatively large, suggesting that severity may be substantially lower than it appears from current case reports. Rapid implementation of infection control measures upon detection of MERS-CoV cases may be limiting onward spread beyond close contacts, and may explain the lack of clear-cut evidence from the epidemiological data available thus far that human-to-human transmission is self-sustaining.

Given the current level of uncertainty around MERS-CoV, it is important that adequate data are collected on future cases to underpin rigorous assessment of the transmission characteristics and severity of MERS-CoV, and the public health threat it may pose. This paper has reviewed the epidemiological investigations needed (Table 2); use of standard protocols – being developed by several groups; see available protocols from WHO [34], the Consortium for the Standardization of Influenza Seroepidemiology (CONSISE) [35] and International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) [36]) – where possible, would be beneficial. Going beyond minimal case reporting, open international collaboration, guided by the International Health Regulations, will impact how this potential epidemic unfolds and prospects for control.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under Grant Agreement nu278433-PREDEMICS, the European Union FP7 EMPERIE project, the NIGMS MIDAS initiative, the Medical Research Council, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

SC received consulting fees from Sanofi Pasteur MSD for a project on the modelling of varicella zoster virus transmission. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SC, MVK, SR, SAD, CF, NMF planned the analysis; MVK compiled the data; SC developed the methods and ran the analysis; SC wrote the first draft; SC, MVK, SR, SAD, CF, NMF edited the paper.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus infections. Geneva: WHO; [Accessed 7 Jun 2013]]. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/disease/coronavirus_infections/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Health Protection Agency (HPA) UK Novel Coronavirus Investigation team. Evidence of person-to-person transmission within a family cluster of novel coronavirus infections, United Kingdom February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(11) doi: 10.2807/ese.18.11.20427-en. pii=20427. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCloskey B, Zumla A, Stephens G, Heymann DL, Memish ZA. Applying lessons from SARS to a newly identified coronavirus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(5):384–5. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pebody R, Zambon M, Watson JM. Novel coronavirus: how much of a threat? We know the questions to ask; we don’t yet have many answers. BMJ. 2013;346:f1301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. 2005;438(7066):355–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng D, de Vlas SJ, Fang LQ, Han XN, Zhao WJ, Sheng S, et al. The SARS epidemic in mainland China: bringing together all epidemiological data. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14 (Suppl 1):4–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AlBarrak AM, Stephens GM, Hewson R, Memish ZA. Recovery from severe novel coronavirus infection. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(12):1265–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bermingham A, Chand MA, Brown CS, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C, et al. Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(40) pii=20290. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchholz U, Müller MA, Nitsche A, Sanewski A, Wevering N, Bauer-Balci, et al. Contact investigation of a case of human novel coronavirus infection treated in a German hospital, October–November 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(8):pii=20406. Available from: http://wwweurosurveillanceorg/ViewArticleaspx?ArticleId=20406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [Accessed 13 Mar 2013];What’s new. Stockholm: ECDC. Novel coronavirus updates. Available from: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/coronavirus-infections/whats-new/Pages/whats_new.aspx.

- 11.Guery B, Poissy J, El Mansouf L, Séjourné C, Ettahar N, Lemaire X, et al. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet. 2013;(13):60982–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60982-4. pii: S0140-6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hijawi B, Abdallat M, Sayaydeh A, Alqasrawi S, Haddadin A, Jaarour N, et al. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19 (Suppl 1):S12–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Memish ZA, Alhakeem R, Stephens GM. Saudi Arabia and the emergence of a novel coronavirus. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19 (Suppl 1):S7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Memish ZA, Zumla AI, Al-Hakeem RF, Al-Rabeeah AA, Stephens GM. Family cluster of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2013 May 29; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303729. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pebody RG, Chand MA, Thomas HL, Green HK, Boddington NL, Carvalho C, et al. The United Kingdom public health response to an imported laboratory confirmed case of a novel coronavirus in September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(40) pii=20292. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Protection Agency (HPA). Third case of novel coronavirus infection identified in family cluster 15 Feb 2013. London: HPA; 2013. Press release. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/NewsCentre/NationalPressReleases/2013PressReleases/1302153rdcaseofcoronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health Protection Agency (HPA) Case of novel coronavirus identified in the UK. 11 Feb 2013. London: HPA; 2013. Press release. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/NewsCentre/NationalPressReleases/2013PressReleases/130211statementonlatestcoronaviruspatient/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Protection Agency (HPA) Further UK case of novel coronavirus. 13 Feb 2013. London: HPA; 2013. Press release. Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/NewsCentre/NationalPressReleases/2013PressReleases/130213statementonlatestcoronaviruspatient/ [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1814–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health (MOH) A new case of coronavirus recorded in Al-Ahsa and three cases passed away in the Eastern Region. 29 May 2013. Riyadh: MOH; 2013. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/Corona/PressReleases/Pages/PressStatement-2013-05-29-001.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 21.ProMED-mail. Novel coronavirus - Saudi Arabia (15): new case. Archive Number 20121104.1391285. 11 Apr 2012. Available from: http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20121104.1391285.

- 22.ProMED-mail. Novel coronavirus - Eastern Mediterranean (17): Saudi Arabia. 2013 May 3; Archive Number 20130503.1688355. Available from: http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20130503.1688355.

- 23.ProMED-mail. Novel coronavirus - Eastern Mediterranean (18): Saudi Arabia. 2013 May 5; Archive Number 20130505.1693290. Available from: http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20130505.1693290.

- 24.ProMED-mail. Novel coronavirus - Eastern Mediterranean (21): Saudi Arabia. 2013 May 9; Archive Number 20130509.1701527. Available from: http://www.promedmail.org/direct.php?id=20130509.1701527.

- 25.World Health Organization (WHO) Middle East respiratory syndrome- coronavirus - update 29 May 2013. Geneva: WHO; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_05_29_ncov/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cauchemez S, Epperson S, Biggerstaff M, Swerdlow D, Finelli L, Ferguson NM. Using routine surveillance data to estimate the epidemic potential of emerging zoonoses: application to the emergence of US swine origin influenza A H3N2v virus. PLoS Med. 2013;10(3):e1001399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills CE, Robins JM, Lipsitch M. Transmissibility of 1918 pandemic influenza. Nature. 2004;432(7019):904–6. doi: 10.1038/nature03063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallinga J, Teunis P. Different epidemic curves for severe acute respiratory syndrome reveal similar impacts of control measures. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):509–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Kerkhove MD, Broberg E, Engelhardt OG, Wood J, Nicoll A CONSISE steering committee. The consortium for the standardization of influenza seroepidemiology (CONSISE): a global partnership to standardize influenza seroepidemiology and develop influenza investigation protocols to inform public health policy. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2013;7(3):231–4. doi: 10.1111/irv.12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jansen VA, Stollenwerk N, Jensen HJ, Ramsay ME, Edmunds WJ, Rhodes CJ. Measles outbreaks in a population with declining vaccine uptake. Science. 2003;301(5634):804. doi: 10.1126/science.1086726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson NM, Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Anderson RM. Public health. Public health risk from the avian H5N1 influenza epidemic. Science. 2004;304(5673):968–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1096898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley S, Kwok KO, Wu KM, Ning DY, Cowling BJ, Wu JT, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza based on paired sera from a longitudinal community cohort study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antia R, Regoes RR, Koella JC, Bergstrom CT. The role of evolution in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nature. 2003;426(6967):658–61. doi: 10.1038/nature02104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization (WHO) Case-control study to assess potential risk factors related to human illness caused by novel coronavirus. Geneva: WHO; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/NovelCoronaCaseControlStudyPotentialRiskFactors_17May13.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The CONSISE Steering Committee. [Accessed 5 Jun 2013];Novel coronavirus (MERS-CoV). The Consortium for the Standardization of Influenza Seroepidemiology (CONSISE). CONSISE. Available from: http://consise.tghn.org/articles/novel-coronavirus-ncov/

- 36.International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) [Accessed 5 Jun 2013];Resources ISARIC. Available from: http://isaric.tghn.org/articles/