Summary

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The pathogenesis by the causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is still not fully understood. We have previously reported that M. tuberculosis Rv3586 (disA) encodes a diadenylate cyclase, which converts ATP to cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP). In this study, we demonstrated that a protein encoded by Rv2837c (cnpB) possesses c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity and cleaves c-di-AMP exclusively to AMP. Our results showed that in M. tuberculosis, deletion of disA abolished bacterial c-di-AMP production, whereas deletion of cnpB significantly enhanced the bacterial c-di-AMP accumulation and secretion. The c-di-AMP levels in both mutants could be corrected by expressing the respective gene. We also found that macrophages infected with ΔcnpB secreted much higher levels of IFN-β than those infected with the wildtype (WT) or the complemented mutant. Interestingly, mice infected with M. tuberculosis ΔcnpB displayed significantly reduced inflammation, less bacterial burden in the lungs and spleens, and extended survival compared to those infected with the WT or the complemented mutant. These results indicate that deletion of cnpB results in attenuated virulence, which is correlated with elevated c-di-AMP levels.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, c-di-AMP, phosphodiesterase, diadenylate cyclase, IFN-β, virulence

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the number one killer worldwide due to a single infectious bacterial agent, and the global burden of TB remains enormous. In 2012, there were an estimated 8.6 million new TB cases and 1.3 million people died from the infection (WHO, Global Tuberculosis Report 2013). Our knowledge about the causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is still limited. Therefore, it is essential to understand the biology of this pathogen in order to eradicate the infection.

Bacterial second messengers are molecules that control important signaling cascades in bacteria as well as the host during infection. For example, cyclic AMP (cAMP) is a ubiquitous second messenger that has been studied for several decades in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. It has been extensively reported to regulate bacterial catabolite repression and microbial virulence (McDonough & Rodriguez, 2011). Signaling by cAMP in M. tuberculosis has been well established (Bai et al., 2011a, McDonough & Rodriguez, 2011, Shenoy & Visweswariah, 2006b). Most interestingly, M. tuberculosis secretes cAMP directly into the infected macrophages (Agarwal et al., 2009, Bai et al., 2009) and interferes with the signaling pathway of the host.

Recently, cyclic di-AMP (c-di-AMP) was recognized as a new signaling molecule (Witte et al., 2008). It is enzymatically converted from two molecules of ATP by diadenylate cyclase and cleaved by distinct c-di-AMP phosphodiesterases to either phosphoadenylyl adenosine (pApA) (Bai et al., 2013, Corrigan et al., 2011, Rao et al., 2010, Smith et al., 2012, Witte et al., 2013) or AMP (Bai et al., 2013). Most bacteria only have one diadenylate cyclase. However, three diadenylate cyclases have been identified in Bacillus subtilis including DisA, CdaA (also referred as YbbP), and CdaS (also referred to as YojJ) (Mehne et al., 2013, Romling, 2008). These cyclases could be individually disrupted from the genome but could not be deleted together except when one of them was ectopically expressed (Mehne et al., 2013). Thus, c-di-AMP is essential for the viability of B. subtilis. Additionally, diadenylate cyclase encoding genes in Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Mycoplasma pulmonis are all essential (Corrigan et al., 2011, Woodward et al., 2010, Bai et al., 2013), suggesting that c-di-AMP plays an important role in bacterial biology. A transmembrane c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase, GdpP, has been reported in several bacteria including B. subtilis, S. aureus, Lactococcus lactis, L. monocytogenes, and S. pneumoniae (Bai et al., 2013, Corrigan et al., 2011, Rao et al., 2010, Smith et al., 2012, Witte et al., 2013). Recently, a cytosolic c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase, Pde2, has been recognized in S. pneumoniae (Bai et al., 2013), which possesses DHH and DHHA1 domains, but lacks the transmembrane domain, the atypical GGDEF domain, and the PAS domain that are all present in GdpP-like c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase. Overall, c-di-AMP has been linked to bacterial peptidoglycan homeostasis (Corrigan et al., 2011, Luo & Helmann, 2012), cellular resistance to antibiotics (Banerjee et al., 2010, Corrigan et al., 2011, Griffiths & O'Neill, 2012, Luo & Helmann, 2012, Witte et al., 2013), bacterial size and biofilm formation (Corrigan et al., 2011, Pozzi et al., 2012), chain length of S. pneumoniae (Bai et al., 2013), potassium uptake (Bai et al., 2014, Corrigan et al., 2013), bacterial infections (Cron et al., 2011, Pozzi et al., 2012, Witte et al., 2013, Schwartz et al., 2012, Yamamoto et al., 2012), and a class of riboswitch (Nelson et al., 2013). In addition, it has also been shown that c-di-AMP represents a bacterial secondary signaling molecule that triggers a cytosolic pathway of innate immunity (Parvatiyar et al., 2012, Sauer et al., 2011, Schwartz et al., 2012, Woodward et al., 2010, Yamamoto et al., 2012). This response is mediated by STING (stimulator of IFN genes) (Burdette et al., 2011, Jin et al., 2011, Sauer et al., 2011) and DDX41 proteins (Bowie, 2012, Parvatiyar et al., 2012).

In M. tuberculosis, Rv3586 (disA, also referred as dacA) encodes a diadenylate cyclase (Bai et al., 2012, Witte et al., 2008). This protein forms an octamer in solution, which is similar to B. subtilis DisA (Bai et al., 2012). Two motifs, DGA and RHR, are highly conserved in DisA of the two bacterial species. It has been recently reported that synthesis of c-di-AMP by a DisA homolog in Mycobacterium smegmatis is inhibited by RadA through a physical interaction with DisA (Zhang & He, 2013). Furthermore, a c-di-AMP binding transcription factor, DarR, was identified in M. smegmatis, and this transcription factor represses the expression of several genes associated with fatty acid metabolism and transportation (Zhang et al., 2013). However, a DarR ortholog has not been identified in M. tuberculosis. How M. tuberculosis maintains c-di-AMP homeostasis and transduces the signal remains unknown. In this study, we identify and characterize a c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase in this important pathogen.

Results

M. tuberculosis Rv2837c encodes a c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase

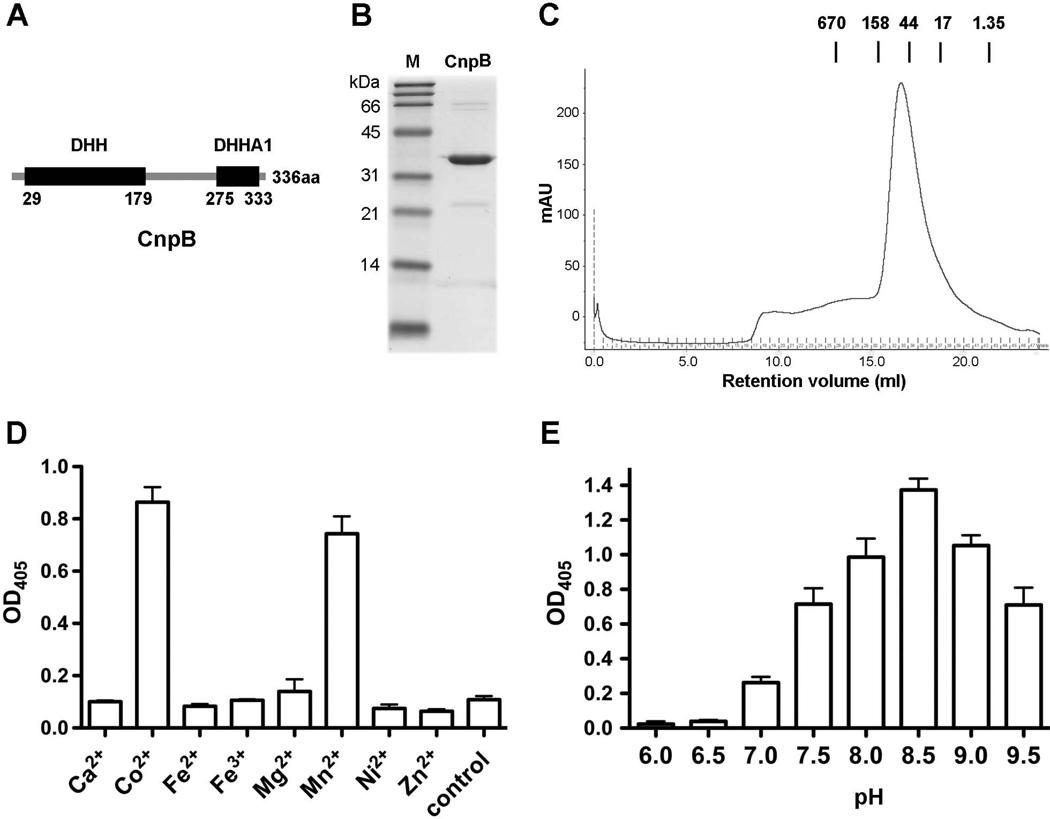

We have characterized M. tuberculosis Rv3586 (DisA) as a diadenylate cyclase (Bai et al., 2012). In this study, we identify a c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase in M. tuberculosis. From sequence analysis with the M. tuberculosis genome (Cole et al., 1998), we were unable to identify a gdpP (or yybT) ortholog, which encodes a well-characterized c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase (Rao et al., 2010, Corrigan et al., 2011). However, Rv2837c is an ortholog of S. pneumoniae pde2 (Bai et al., 2013), which contains a DHH domain and a DHHA1 domain (Fig. 1A). The Rv2837c protein shares 22.5% identity in amino acid sequence with Pde2, suggesting that Rv2837c encodes a putative c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase. Thus, we designated Rv2837c cnpB and the encoded protein CnpB as the second cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase in addition to Rv0805 that has been reported to cleave 2′,3′cAMP and 2′, 3′-cGMP in M. tuberculosis (Keppetipola & Shuman, 2008, Podobnik et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

Purification and characterization of CnpB. (A) Domain architecture of CnpB. The numbers indicated under the DHH and DHHA1 domains are amino acid positions in the full-length protein. (B) His-tagged CnpB was expressed and purified from E. coli, and was analyzed by SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie bright blue. Lane M, broad range protein ladder (BioRad). (C) Gel filtration chromatograph of CnpB. The molecular mass (in kDa) and the retention volumes of the standards are indicated. (D and E) Cleavage of BNPP by purified CnpB in the presence of indicated metal cations (D) or at different pH (E). The reaction in “Control” of panel D was not supplemented with any cation. The data shown in panels D and E are the means of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate the standard errors of the means (SEMs).

We overexpressed His-tagged CnpB in E. coli and purified the protein to homogeneity. The purified protein exhibited an apparent molecular mass of 34 kDa (Fig. 1B). Gel filtration analysis indicated that this protein forms a stable dimer in solution (Fig. 1C), similar to S. pneumoniae Pde2 (Bai et al., 2013). In order to optimize the catalytic activity of CnpB, we first utilized bis-p-nitrophenyl phosphate (BNPP), a nonspecific substrate of phosphatases and phosphodiesterases, to determine the enzymatic activities of CnpB under different conditions. Our results showed that CnpB preferred Co2+ and Mn2+ from the metal cations that we tested (Fig. 1 D). In terms of pH, CnpB exhibited the highest enzymatic activity at pH 8.5 (Fig. 1E). These results are consistent with that of S. pneumoniae Pde2 (Bai et al., 2013).

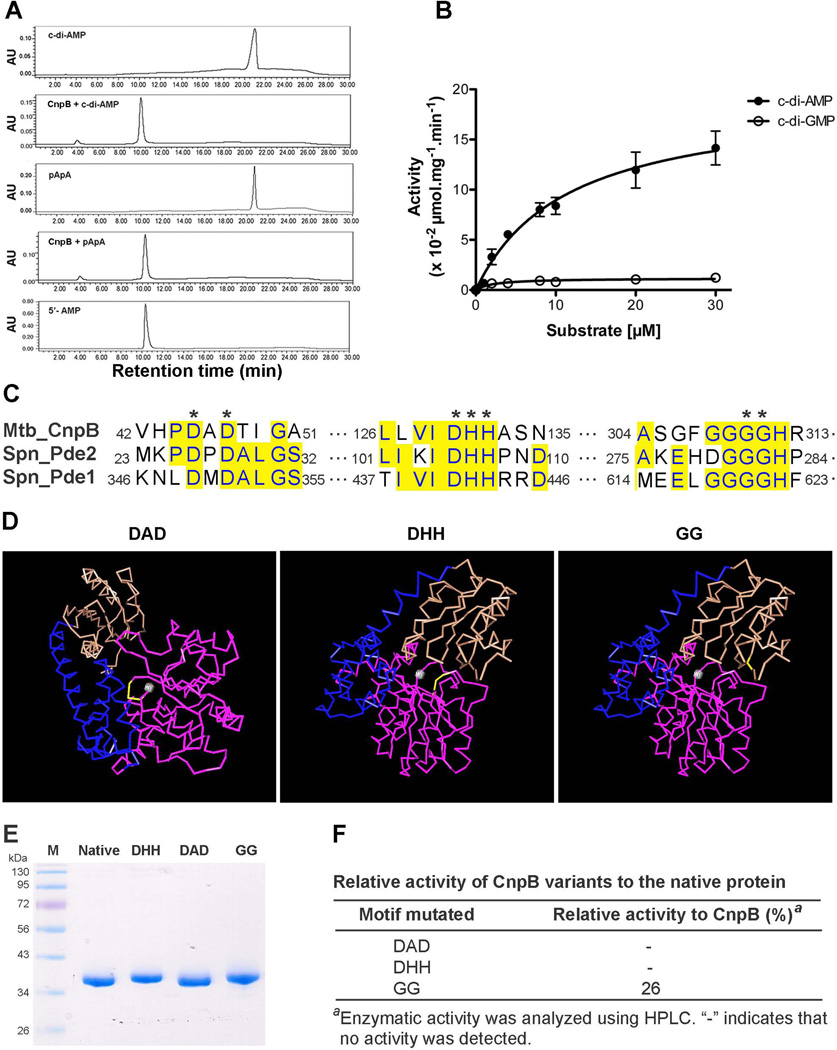

We determined the phosphodiesterase activity of CnpB towards cleavage of c-di-AMP and cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP). Our result showed that CnpB cleaved c-di-AMP exclusively to AMP (Fig. 2A and B) with a Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) of 11.42 ± 2.96 µM. Additionally, CnpB was also capable of converting pApA to AMP (Fig. 2A). These results are also consistent with the activity of S. pneumoniae Pde2 (Bai et al., 2013). Furthermore, CnpB exhibited very low activity in cleavage of c-di-GMP to GMP (Fig. 2B). The preference of CnpB to c-di-AMP over c-di-GMP is similar to the observation with GdpP (Rao et al., 2010). These observations indicate that c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP are cleaved by distinct phosphodiesterases.

Fig. 2.

Phosphodiesterase activity of CnpB. (A) CnpB was incubated with c-di-AMP or pApA, as indicated. Each sample was separated by HPLC and monitored at 254 nm. Purified c-di-AMP, pApA, and AMP were used as standards. (B) Kinetics of CnpB in cleavage of c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP. c-di-AMP or c-di-GMP at indicated concentrations was incubated with CnpB for 1 h. The enzymatic activities were determined using HPLC. The data shown are the means of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate the SEMs. (C) Sequence alignment of M. tuberculosis CnpB with S. pneumoniae Pde1 and Pde2. Identical residues are highlighted in yellow. Highly conserved amino acids in phosphoesterase RecJ domain-containing proteins are indicated with asterisks. (D) Structural modeling of T. thermophilus RecJ (PDB code 1IR6) with Cn3D software. The indicated residues, DAD, DHH, and GG, are shown in yellow. A grey ball indicates Mn2+. DHH domain, DHHA1 domain, and a long helix connecting the two domains are shown in purple, brown, and blue, respectively. (E) Purification of CnpB and CnpB with mutation of DHH, DAD, and GG to AAA, AAA, and AA, respectively. Approximately 2 µg of each indicated protein was loaded. Lane M, Fisher BioReagents EZ-run prestained Rec protein ladder (Fisher Scientific). (F) Enzymatic activity of CnpB variants relative to native CnpB in cleavage of c-di-AMP to AMP. The same amount of CnpB and the indicated proteins were used to determine the activity. The amount of cleaved c-di-AMP detected in the reaction with protein containing GG to AA mutation was compared to that with CnpB, as shown in percentage.

Both DHH and DHHA1 motifs of CnpB are essential for c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity

GdpP possesses two transmembrane domains, a PAS domain, a modified GGDEF domain, a DHH domain, and a DHHA1 domain (Corrigan et al., 2011, Rao et al., 2010). In contrast, CnpB or S. pneumoniae Pde2 only possesses a DHH domain and a DHHA1 domain, which supports the observation that DHH and DHHA1 domains are essential for GdpP’s phosphodiesterase activity (Rao et al., 2010). Sequence analysis revealed that CnpB belongs to phosphoesterase RecJ domain-containing proteins. These proteins possess highly conserved DxD, DHH, and GGGH motifs (Fig. 2C). Structural analysis with C3nD software using Thermus thermophilus RecJ (PDB code 1IR6) as a template displayed that both the DxD and DHH motifs coordinate Mn2+ (Yamagata et al., 2002), while the GGGH residues are structurally adjacent to the DHH motif although it is located in a different domain (Fig. 2D), implicating that these residues might be essential for the enzymatic activity of CnpB. According to the conservation of amino acids in RecJ-like proteins, we replaced both aspartate residues in the DxD motif with alanine, the DHH motif with AAA, or the GGGH motif with GAAH in CnpB (Fig. 2E), and examined the activity of these variants towards cleavage of c-di-AMP. Our result showed that mutation of either the DxD motif or the DHH motif completely abolished the c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity of CnpB, indicating that both motifs are essential for the enzymatic activity (Fig. 2F). Mutation of the GGGH motif also significantly reduced the cleavage of c-di-AMP (Fig. 2F), indicating that the GGGH motif also plays a substantial role in cleavage of c-di-AMP. The enzymatic activity of these CnpB variants is consistent with the implication from the structural modeling.

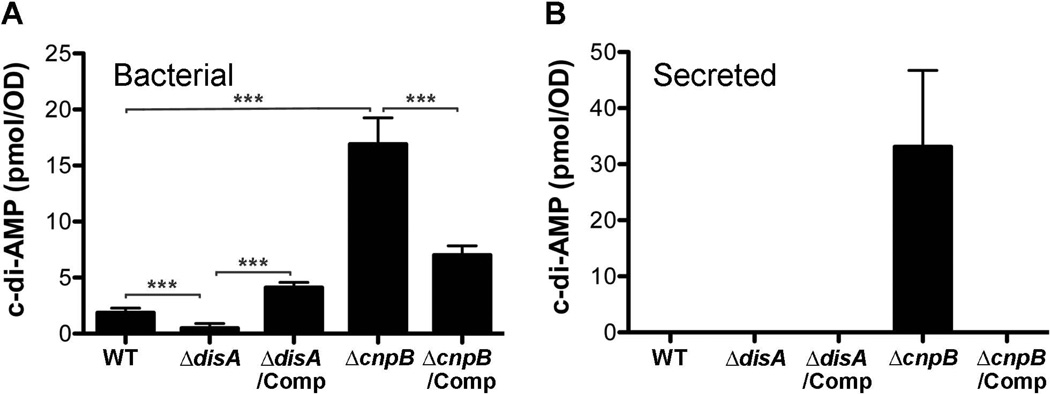

Both DisA and CnpB contribute to c-di-AMP homeostasis in M. tuberculosis

In order to examine the biological role of c-di-AMP in M. tuberculosis, we generated ΔdisA and ΔcnpB mutants in M. tuberculosis H37Rv strain by homologous recombination and complemented both mutants with their open reading frames (ORFs) controlled by M. tuberculosis Rv0805 or tuf promoter (Table 1). Both complemented strains were engineered in a single copy and integrated at an att-int site (Bai et al., 2011b). We prepared bacterial lysates and detected c-di-AMP levels using a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Our result showed that deletion of disA in M. tuberculosis abolished the production of bacterial c-di-AMP (Fig. 3A), indicating that DisA might be the unique diadenylate cyclase in this pathogen. In contrast, deletion of cnpB significantly enhanced the levels of c-di-AMP (Fig. 3A). The c-di-AMP levels of both mutants could be corrected by complementation with the respective gene, indicating that the activities of both DisA and CnpB within M. tuberculosis are consistent to the in vitro analyses, and both enzymes are required for maintaining c-di-AMP homeostasis in M. tuberculosis. We also determined the c-di-AMP levels directly in 7-d culture supernatant of each bacterial strain. Our results showed that c-di-AMP was undetectable in the culture supernatant with our assay for all the strains except the ΔcnpB mutant (Fig. 3B). The relatively large amount of c-di-AMP accumulated in ΔcnpB and secreted by this strain suggests that the M. tuberculosis wildtype (WT) may also secrete c-di-AMP, but at levels that are beyond our detectable limit, which is ~10 nM.

Table 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pMBC851 | M. tuberculosis knockout plasmid; Hygr | (Bai et al., 2011b) |

| phAE159 | Knockout phasmid; Carbr | (Vilcheze et al., 2008) |

| pMBC1193 | pMBC851 carrying disA downstream fragment; Hygr | This study |

| pMBC1194 | pMBC1193 carrying disA upstream fragment; Hygr | This study |

| pMBC1206 | phAE159 carrying pMBC1194 plasmid DNA; Hygr | This study |

| pJSC407 | M. tuberculosis knockout plasmid; Hygr | (Grundner et al., 2008) |

| pGB128 | pJSC407 carrying cnpB upstream fragment; Hygr | This study |

| pGB132 | pGB128 carrying cnpB downstream fragment; Hygr | This study |

| pGB139 | phAE159 carrying pGB132 plasmid DNA; Hygr | This study |

| pET28a(+) | Expression plasmid; Kanr | Novagen |

| pGB136 | pET28a(+) carrying cnpB ORF; Kanr | This study |

| pGB152 | pET28a(+) carrying cnpB ORF with DAD to AAA mutation; Kanr | This study |

| pGB153 | pET28a(+) carrying cnpB ORF with DHH to AAA mutation; Kanr | This study |

| pGB156 | pET28a(+) carrying cnpB ORF with GG to AA mutation; Kanr | This study |

| pMBC304 | pCRII carrying M. tuberculosis att-int sequence; Kanr; Apr | This study |

| pMBC1258 | pMBC304 carrying M. tuberculosis tuf promoter; Kanr; Apr | This study |

| pMBC1260 | pMBC304 carrying Rv0805 promoter; Kanr; Apr | This study |

| pGB086 | pMBC1258 carrying disA ORF; Kanr; Apr | This study |

| pGB120 | pMBC1260 carrying cnpB ORF; Kanr; Apr | This study |

Hygr, hygromycin resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Carbr, carbenicillin resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance.

Fig. 3.

Determination of bacterial (A) and secreted (B) c-di-AMP. Bacteria were grown in Sauton’s broth for 7 d and were harvested by centrifugation. The c-di-AMP levels in the supernatant (Secreted) and in the bacterial lysate (Bacterial) were determined using ELISA as described in the Experimental Procedures section. The data shown are the means of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate the SEMs, ***, P < 0.001.

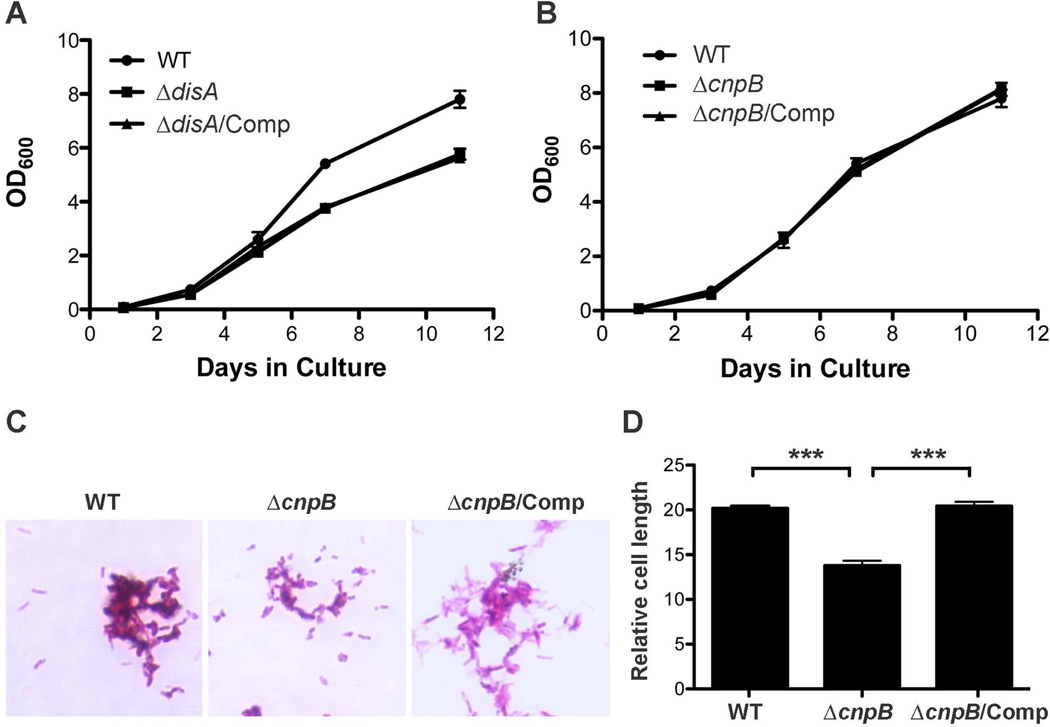

Deletion of cnpB reduces bacterial length of M. tuberculosis

It has been reported that deletion of gdpP in S. aureus significantly reduces bacterial size (Corrigan et al., 2011). In this study, we grew M. tuberculosis WT, ΔdisA, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutants in mycomedium and determined the bacterial growth rate by monitoring optical density (OD) at 600 nm (OD600). Our result showed that ΔdisA grew slightly slower than the WT but the defective growth could not be corrected by complementation (Fig. 4A), suggesting that it is likely caused by a polar effect. The growth rate of ΔcnpB is indistinguishable from that of the WT (Fig. 4B). For the bacterial size, ΔdisA is similar to the WT (not shown). Interestingly, the bacterial length of ΔcnpB was reduced approximately 30% relative to that of the WT and the complemented mutant analyzed using Image J software (Fig. 4C and D), which is consistent with the report of S. aureus. Our result suggests that enhanced c-di-AMP in M. tuberculosis modulates bacterial size similar to S. aureus.

Fig. 4.

Growth curve and bacterial size of M. tuberculosis and its derivatives. (A and B) Growth curve of M. tuberculosis WT, the indicated mutants, and the complemented mutants in mycomedium. The growth was monitored at days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 11. The data shown are the means of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate the SEMs. Note that the growth rate of ΔdisA is the same as the complemented ΔdisA (A) and both ΔcnpB and the complemented mutant are indistinguishable from the WT (B). (C) Morphology of ΔcnpB. M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Kinyoun acid-fast stain (Kinyoun, 1915). (D) Determination of bacterial size. Bacteria were grown in mycomedium for 7 d and analyzed microscopically. The relative cell length (in arbitrary unit) of 100 bacteria per strain was analyzed with Image J software. The data shown are the means of 100 bacteria. The error bars indicate the SEMs. ***, P < 0.0001. The graph is a representative of three independent experiments.

c-di-AMP produced by M. tuberculosis induces IFN-β production

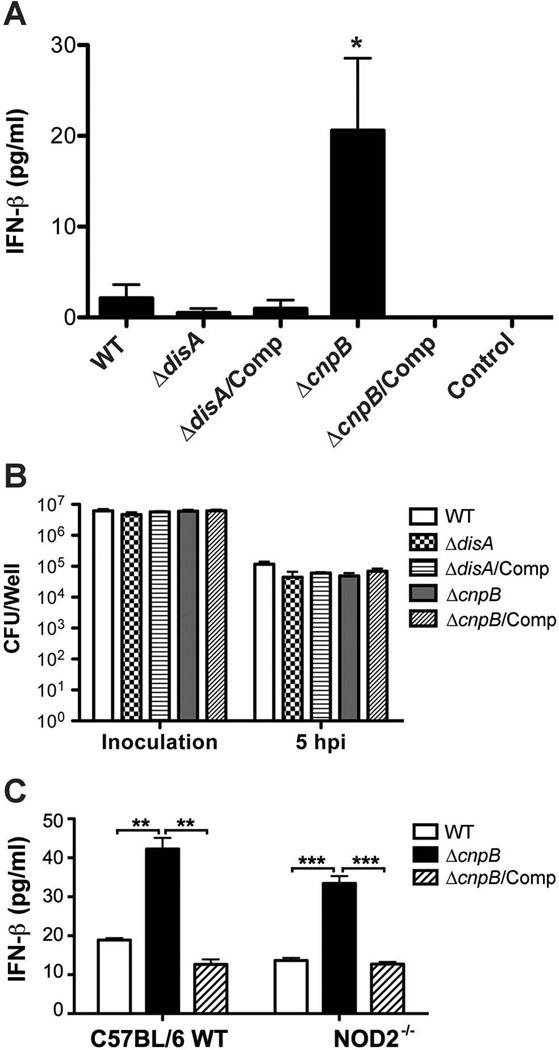

It has been reported that c-di-AMP stimulates a host type I IFN response during infection of L. monocytogenes or C. trachomatis (Barker et al., 2013, Woodward et al., 2010). Additionally, mycobacterial DNA and peptidoglycan have also been shown to stimulate a type I IFN response (Manzanillo et al., 2012, Pandey et al., 2009). To characterize the host type I IFN response to M. tuberculosis ΔdisA and ΔcnpB, we first infected bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) isolated from C57BL/6 WT mice with M. tuberculosis and its derivatives and examined the IFN-β secretion from the infected cells. Our result showed that by 5 h post-infection, IFN-β secreted by the ΔdisA infected macrophages was approximately 4-fold less than those infected by the WT. In contrast, the ΔcnpB infected macrophages secreted 10-fold more IFN-β than those infected with the WT (Fig. 5A). This result is coincident with the secretion of c-di-AMP by ΔcnpB (Fig. 3B). The enhanced IFN-β secretion by macrophages infected with ΔcnpB is unlikely contributed by bacterial DNA since similar numbers of viable bacteria were recovered from macrophages infected with WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant, respectively, at 5 h post-infection (Fig. 5B). However, the present results do not fully rule out the possibility that perturbations of cell wall metabolism in ΔcnpB are leading to increased release of DNA. Our ongoing studies using cGAS−/− and STING−/− mice will distinguish these two possibilities. Furthermore, it is well known that bacterial peptidoglycan can induce a type I interferon response through a NOD2 signaling pathway. However, BMDMs isolated from WT and NOD2−/− mice secreted similar levels of IFN-β after infection with either M. tuberculosis WT or ΔcnpB (Fig. 5C), indicating that the enhanced IFN-β response to ΔcnpB is not stimulated by bacterial peptidoglycan. Together, our results suggest that c-di-AMP secreted by M. tuberculosis stimulates an IFN-β response in infected macrophages.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of IFN-β secreted by BMDMs. (A) IFN-β secreted by BMDMs of WT mice 5 h post-infection with M. tuberculosis and its derivatives. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 2 × 106 cells/well. “Control” denotes BMDM cells without infection. The data shown are the means of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate the SEMs. *, P < 0.05 in a one-tailed t-test compared to the WT infected macrophages. (B) Bacteria recovered from infected BMDMs in experiments shown in panel A. The data shown are the means of three independent experiments. The error bars indicate the SEMs. (C) IFN-β secreted by BMDMs of WT and NOD2−/− mice 5 h post-infection with M. tuberculosis and its derivatives, respectively. BMDM cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/well in triplicates. The data shown are the means of samples in triplicate. The error bars indicate the SEMs. **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001.

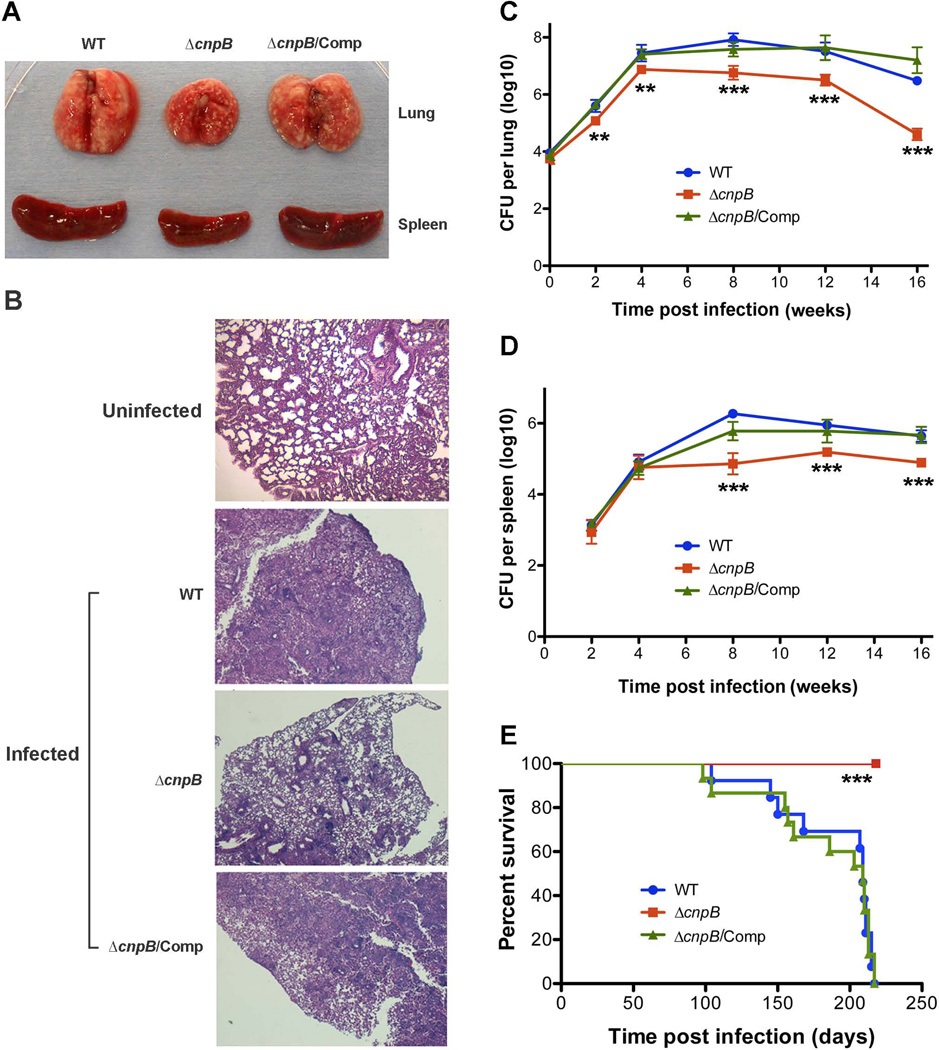

Deletion of cnpB in M. tuberculosis attenuates virulence during infection of mice

In order to investigate the role of cnpB in virulence, mice were infected with M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant, respectively, examined for pathology and bacterial burden in the lungs and spleens at 2, 4, 8, 16 weeks post-infection, and monitored for survival rate over time. From 4 weeks post-infection, the lungs and spleens of mice infected with ΔcnpB exhibited smaller sizes compared to those infected with the WT or the complemented mutant (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, the lungs of mice infected with ΔcnpB displayed less inflammation compared to those infected with the WT or the complemented mutant (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that deletion of cnpB reduced the immunopathology in the infected lungs and spleens. At 1 d post-infection, similar numbers of bacteria were recovered from the lungs of mice infected with the WT, ΔcnpB, or the complemented mutant (Fig. 6C), indicating that mice were initially infected with similar numbers of bacteria. From 8 weeks post-infection, the bacterial burden in the lungs of mice infected with ΔcnpB was 10 to 50-fold less compared to those infected with the WT or the complemented mutant (Fig. 6C). Meanwhile, the bacterial burden in the spleens of mice infected with ΔcnpB was 5 to 10-fold less than those infected with the WT or the complemented mutant (Fig. 6D). These results are in accordance with the observation that mice infected with M. tuberculosis ΔdisA exhibited exacerbated lung pathology and bacillary load (Dey et al., 2013). For the survival rate, all mice infected with either the WT or the complemented ΔcnpB mutant succumbed to the experiment. The median time of survival for mice infected with the WT and the complemented mutant were 208 d and 203 d, respectively. However, all 15 mice infected with ΔcnpB survived the experiment and appeared healthy throughout the experiment. The experiment was terminated at 220 d post-infection (Fig. 6E). Taken together, deletion of cnpB in M. tuberculosis attenuates virulence in the mouse model of infection, which is likely due to the significantly elevated c-di-AMP levels.

Fig. 6.

Evaluation of virulence of ΔcnpB in a mouse infection model. (A) Gross pathology of lungs and spleens of the mice at 8 weeks post-infection with M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant. Data shown is a representative of 5 mice for each group. (B) H&E stained lung sections of an uninfected mouse or infected mice at 8 weeks post-infection with M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant. The data shown is a representative of 5 mice for each group. Note that the lung section of an uninfected BALB/c mouse was stained separately from the infected lungs. (C and D) Bacterial burden in the lungs (C) and spleens (D) of the infected mice at the indicated time points post-infection with M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant (n = 5). The data shown are the means of CFU. The error bars indicate the SEMs. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (E) Survival rate of mice infected with M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant (n = 15). Mice were infected with approximately 10,000 CFU of each strain to the lungs using an aerosol chamber. ***, P < 0.001 analyzed using Log-rank test.

Discussion

M. tuberculosis CnpB has been shown to dephosphorylate 3'-phosphoadenosine 5'-phosphate (pAp) to AMP (Postic et al., 2012). In this study, we demonstrated that M. tuberculosis cnpB encodes a c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase and that deletion of cnpB significantly enhanced c-di-AMP accumulation and secretion in M. tuberculosis. Furthermore, M. tuberculosis ΔcnpB exhibited reduced virulence in the mouse TB model. Interestingly, the attenuation of virulence we observed is consistent with previous reports that deletion of c-di-AMP or c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase inhibits bacterial virulence. For instance, deletion of both pde1 and pde2, which possess c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity, significantly attenuated virulence of S. pneumoniae (Cron et al., 2011, Bai et al., 2013). Moreover, deletion of gdpP in S. pyogenes also attenuated virulence in a murine subcutaneous infection model (Cho & Kang, 2013). Additionally, deletion of c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase in several pathogens reduces virulence (Bobrov et al., 2011, Kulasakara et al., 2006, Ryan et al., 2009, Sultan et al., 2010, Tamayo et al., 2008, Tischler & Camilli, 2005), whereas deletion of diguanylate cyclase may result in elevated or no change in virulence (Bobrov et al., 2011, Romling et al., 2013, Tischler & Camilli, 2005). Taken together, we conclude that the attenuated virulence during infection of mice with ΔcnpB is caused by the over production of c-di-AMP.

The mechanism by which c-di-AMP attenuates virulence is unclear. It is likely that c-di-AMP induces a protective immune response and/or regulates expression of bacterial virulence genes. Several studies have demonstrated that c-di-AMP stimulates a STING-dependent type I IFN response during infection with L. monocytogenes (Jin et al., 2011, Sauer et al., 2011) and C. trachomatis (Barker et al., 2013). Our result also suggests that M. tuberculosis ΔcnpB induces stronger type I IFN response than the WT. However, the induction of type I IFN has mostly been associated with pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis (Berry et al., 2010, Teles et al., 2013, Stanley et al., 2007), and it has been shown that signaling through type I IFNR is important for full virulence of M. tuberculosis (Stanley et al., 2007). On the other hand, a protective role of type I IFN during M. tuberculosis may not be completely ruled out, as a recent study established a model in which type I IFN limits the number of cells that M. tuberculosis can infect in the lungs (Desvignes et al., 2012). Moreover, it has also been shown that both c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP can activate NLRP3 inflammasome, which leads to production of IL-1β (Abdul-Sater et al., 2013). Our future study will determine whether it is type I IFN or other c-di-AMP stimulated host response that leads to the attenuated infection of ΔcnpB.

It has been noted that DAC domain-containing proteins are most frequently found in Gram-positive bacteria phyla Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, and most bacteria contain only one diadenylate cyclase (Corrigan & Grundling, 2013). In contrast, c-di-GMP producing bacteria usually possess many more c-di-GMP synthesis/cleavage enzymes (Romling et al., 2013). Interestingly, both c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP associated genes have been identified in some bacteria, such as B. subtilis (Chen et al., 2012, Gao et al., 2013, Luo & Helmann, 2012, Mehne et al., 2013, Rao et al., 2010, Witte et al., 2008) and M. tuberculosis (Bai et al., 2012, Gupta et al., 2010). We have reported that M. tuberculosis DisA has a preference for ATP, but not GTP, as a substrate (Bai et al., 2012). In this study, we showed that CnpB specifically cleaves c-di-AMP, rather than c-di-GMP, which is consistent with the activity of GdpP in B. subtilis (Rao et al., 2010). Additionally, the M. tuberculosis Rv1354c protein converts GTP to c-di-GMP, and both Rv1357c and Rv1354c proteins are able to hydrolyze c-di-GMP (Gupta et al., 2010). Therefore, the enzymes for synthesis and cleavage of both c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP are distinct. In contrast to B. subtilis, M. tuberculosis has fewer enzymes for both c-di-AMP and c-di-GMP metabolism. Thus, we will explore whether there is any overlapping between the signaling pathways of the two dinucleotides in M. tuberculosis.

Little is known about how bacteria secrete c-di-AMP, except that L. monocytogenes is capable of secreting c-di-AMP via efflux pumps (Schwartz et al., 2012, Woodward et al., 2010). In this study, a large amount of c-di-AMP was detected in ΔcnpB and its culture supernatant, indicating that M. tuberculosis may also secrete c-di-AMP. However, we were unable to detect c-di-AMP in the culture supernatant of the M. tuberculosis WT, suggesting that the levels of c-di-AMP in the culture supernatant might be less than 10 nM, which is much lower than that of cAMP secreted by M. tuberculosis (Agarwal et al., 2009, Bai et al., 2009). This is not a surprise since at least 15 adenylate cyclases have been found in M. tuberculosis (Bai et al., 2011a, McCue et al., 2000, McDonough & Rodriguez, 2011, Shenoy & Visweswariah, 2006a), whereas only one diadenylate cyclase has been identified in this pathogen (Bai et al., 2012).

Presently, only a few studies have explored how the signal of c-di-AMP is transduced inside bacteria. A transcription factor DarR has been reported to bind c-di-AMP and regulate fatty acid metabolism (Zhang et al., 2013). However, the direct role of c-di-AMP in gene regulation was not addressed in that report, and we were unable to identify a homology of DarR in M. tuberculosis. Recent reports identified a c-di-AMP binding protein in both S. aureus (Corrigan et al., 2013) and S. pneumoniae (Bai et al., 2014) that plays a role in potassium uptake. At least in S. pneumoniae, c-di-AMP impairs potassium uptake by reducing the interaction between the c-di-AMP binding protein and a potassium transporter (Bai et al., 2014). The biological role of c-di-AMP in M. tuberculosis remains largely unexplored, which warrants further investigation.

In summary, our study demonstrated that deletion of c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase cnpB in M. tuberculosis attenuates virulence in a mouse infection model. The attenuation is likely caused by a protective immune response induced by c-di-AMP and/or by c-di-AMP mediated regulation of virulence gene expression in M. tuberculosis. Nonetheless, the protective role of c-di-AMP during infection may provide insights into novel vaccine exploration.

Note

During the revision of this manuscript, a paper presented that M. tuberculosis Rv2837c encodes a c-di-AMP phosphodiesterase (Manikandan, et al. 2014), which is consistent with our result.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

M. tuberculosis H37Rv was grown in mycomedium, which is Middlebrook 7H9 medium (BD) supplemented with 0.5% glycerol, 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC), 0.05% Tween-80, as previously described (Florczyk et al., 2003) or on Middlebrook 7H10 agar (BD) supplemented with 10% OADC, and 0.01% cycloheximide. Fresh cultures were inoculated from frozen stocks for every experiment. Bacteria were typically used at late log phase after 7 days of growth. Cultures were grown in tissue culture flasks standing with ambient air. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth or on Luria-Bertani agar plates. Kanamycin at 25 µg/ml or hygromycin at 50 µg/ml was added for recombinant strains. All cultures were grown at 37°C, except that M. smegmatis was grown at 30°C.

Expression and purification of CnpB

M. tuberculosis cnpB ORF was amplified by PCR using primers listed in Table 2 and M. tuberculosis genomic DNA as template. The PCR product was cloned into pET28a(+) (Novagen) to generate pGB136. Mutations of DxD, DHH, and GGGH motifs in cnpB were generated by overlapping PCR, and the DNA fragments with these mutations were cloned into pET28a(+) to generate pGB152, pGB153, and pGB156, respectively. The four recombinant plasmids were individually maintained in E. coli BL21(DE3). CnpB and its variants were expressed and purified as we reported previously (Bai et al., 2012, El Qaidi et al., 2013). Briefly, Overnight culture was inoculated in 500 ml LB broth containing 25 µg/ml kanamycin and incubated at 37°C with shaking to an OD600 of 0.6. The cultures were then cooled down to room temperature followed by the addition of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.1 mM. After induction at room temperature for 4 h, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 10 min and the pellets were stored at −80°C until use.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Oligo sequence (5′ to 3′)a | Purposeb |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis | ||

| KM2889 | gcggccgcggtgcagaccatgtccacc | disA upstream; For |

| KM2890 | gcggccgcgacagcctcacgcagggtcg | disA upstream; Rev |

| KM2891 | ccatagattggcggaatcgaccatcagc | disA downstream; For |

| KM2892 | ccatcttttggaacaggccaccgttaacacg | disA downstream; Rev |

| KM2893 | cgtgcacaccgtgctcgacc | Verify disA upstream crossover; For |

| KM2084 | cggccgcataatacgactca | Verify disA upstream crossover; Rev |

| KM2894 | gcgaggaggtctgagttacc | Verify disA downstream crossover; For |

| KM2585 | aacggcaggtatatgtgatgg | Verify disA downstream crossover; Rev |

| KM2917 | tctgcgatggtggcttctcc | disA internal; For |

| KM2918 | cggtcaatacgtgacgttcc | disA internal; Rev |

| JY207 | tttgatatctactactcggtcatctacc | cnpB upstream; For |

| JY208 | tttaagcttgtcgaccagctcactccttgg | cnpB upstream; Rev |

| JY209 | ttttctagatggccgcggggtatacgacc | cnpB downstream; For |

| JY210 | tttggtacctcgctagcgaatcaagaac | cnpB downstream; Rev |

| JY211 | tgtgcgcgccgaaggcaagg | Verify cnpB upstream crossover; For |

| JY002 | tcgacgacctgcaggcatgc | Verify cnpB upstream crossover; Rev |

| JY003 | actggcgcagttcctctggg | Verify cnpB downstream crossover; For |

| JY212 | cagcgaaaacgccgtcaccc | Verify cnpB downstream crossover; Rev |

| JY234 | tgggcgatctaactgattcc | cnpB internal; For |

| JY235 | catcaaggtcctgctgacgg | cnpB internal; Rev |

| Complementation | ||

| KM3070 | tttaagcttacacccgaggactacatggg | tuf promoter; For |

| KM3071 | tttggtacccgccacttttgtgtcctcc | tuf promoter; Rev |

| KM3072 | tttaagcttgatgtcggctcgtgagttgc | Rv0805 promoter; For |

| KM3073 | tttggtacccaccgaggtgccaaccctc | Rv0805 promoter; Rev |

| KM3098 | tgatcatatgcacgctgtgactcgtcc | disA ORF; For |

| KM3099 | tgatcaaaggcggataattattgatcgc | disA ORF; Rev |

| JY213 | tttggtaccgtgacgacgatcgacccaagg | cnpB ORF; For |

| JY214 | tttggatccgccagctgcgcgatctgacg | cnpB ORF; Rev |

| Overexpression | ||

| JY217 | cggcatatggtgacgacgatcgacccaag | cnpB ORF; For |

| JY214 | tttggatccgccagctgcgcgatctgacg | cnpB ORF; Rev |

| JY224 | gtctgccacgtccaccccgcagccgcaaccatcggcgccggattg | CnpB DAD to AAA mutation; For |

| JY225 | caatccggcgccgatggttgcggctgcggggtggacgtggcagac | CnpB DAD to AAA mutation; Rev |

| JY226 | cgggagctcctggtaatcgcagcagccgcctccaacgacctgttc | CnpB DHH to AAA mutation; For |

| JY227 | gaacaggtcgttggaggcggctgctgcgattaccaggagctcccg | CnpB DHH to AAA mutation; Rev |

| JY232 | gttgcctctgggttcggtgccgctggtcaccggctggccgcg | CnpB GG to AA mutation; For |

| JY233 | cgcggccagccggtgaccagcggcaccgaacccagaggcaac | CnpB GG to AA mutation; Rev |

The restriction site is underlined if presents in an oligo.

For, forward primer; Rev, reverse primer.

Each bacterial pellet was resuspended in 50 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, pH7.5) with 1× protease inhibitor (Roche) and sonicated on ice for 10 min with 5 s pulse and 10 s interval. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA agarose column pre-equilibrated with buffer A at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The column was subsequently washed with 50 ml of buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) and 50 ml buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole, pH7.5) at 1 ml/min. The His-tagged proteins were eluted with 10 ml buffer D (50 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) at 0.5 ml/min. All eluted fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and collections were dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. The purified proteins were stored in PBS with 10% glycerol at −80°C until use.

Gel filtration

Size-exclusion chromatography experiment was performed with a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare) and connected to a Gradiphrac Automatic Sampler (Amersham Biosciences). The column was equilibrated and eluted at a constant flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with 10% (v/v) glycerol in PBS. Molecular mass of the protein was determined by using a Gel Filtration Standard (Bio-Rad) per the instruction of the Gel Filtration Principles and Methods (GE Healthcare).

Cleavage of BNPP

Reaction (50 µl) mixtures consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl at specified pH, 10 mM NaCl, 5 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM of specified metal cation, and 2 mM BNPP. The reaction was initiated by addition of 3 µM purified CnpB and was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Relative BNPP cleavage was determined by measuring OD at 405 nm (OD405) using a microplate reader (Spectrum Max 340PC, Molecular Devices). The assay conditions used for cation screening contained 0.1 mM CaCl2, CoCl2, FeCl2, Fe(NO3)3, MgCl2, MnCl2, NiSO4, or ZnSO4. For pH analysis, reaction mixtures consisted of 0.1 mM MnCl2 and 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 9.0, or 9.5.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The reaction (10 µl) mixtures to determine the activity of CnpB contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM MnCl2, and 0.5 mM indicated nucleotide. The reaction was initiated by adding 3 µM CnpB and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, each reaction was terminated by adding 1 µl of 0.5 M EDTA and diluted 1:5 with water. Finally, 20 µl of each sample was injected and separated by reverse-phase HPLC with a C-18 column (250×4.6 mm, Vydac) using a Waters 625 LC system equipped with a 996 Photodiode Array Detector and a 717 Autosampler (Waters). Samples were eluted using the same buffers and program as previously reported (Ryjenkov et al., 2005). Nucleotides were monitored at 254 nm.

Construction and complementation of mutants

In this study, M. tuberculosis ΔdisA was generated using homologous recombination as previously reported (Bai et al., 2011b). Briefly, upstream and downstream fragments of disA were amplified by PCR using M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA as template. The two flanking DNA fragments were sequentially sub-cloned into pMBC851 at NotI and PflMI sites, respectively, and sequencing verified to generate pMBC1194. This plasmid was linearized with PacI and ligated with PacI-digested shuttle phasmid phAE159 (kindly provided by Dr. William Jacobs) (Vilcheze et al., 2008). The ligation mixture was packaged using MaxPlax lambda packaging extracts (Epicentre Biotechnoloies) and transduced into E. coli HB101. Phasmid DNA (designated pMBC1206) was prepared from hygromycin-resistant colonies and transformed into M. smegmatis mc2155. Phages were prepared from transformed M. smegmatis similar as earlier reports (Bardarov et al., 2002, Tufariello et al., 2004). M. tuberculosis grown to log phase were infected with high titer phages (Bardarov et al., 2002). ΔdisA candidates were screened by PCR using primers as listed in Table 2.

M. tuberculosis ΔcnpB mutant was generated similarly but using a different plasmid. Briefly, an upstream fragment was cloned into pJSC407 (Kindly provided by Dr. Jeffery Cox) (Grundner et al., 2008) between EcoRV and HindIII sites to generate pGB128, and a downstream fragment of cnpB was then cloned into pGB128 between XbaI and KpnI sites to generate pGB132. This plasmid was then used to generate phage and delete cnpB using the same procedure as that for deletion of disA.

To complement the mutants, M. tuberculosis tuf promoter was amplified by PCR and cloned into pMBC304 between HindIII and KpnI sites to generate pMBC1258, The disA ORF was then cloned into this plasmid to generate pGB086, and this plasmid was transformed into ΔdisA to complement the mutation. Meanwhile, Rv0805 promoter was amplified by PCR and cloned into pMBC304 between HindIII and KpnI sites to generate pMBC1260. The cnpB ORF was then cloned into this plasmid to generate pGB120. This plasmid was eventually transformed into ΔcnpB to complement the mutation.

Determination of bacterial growth and size

M. tuberculosis WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant were grown in mycomedium until 11 d post inoculation. Bacterial growth was determined on day 1, 3, 5, 7, and 11 by measuring OD600. To examine bacterial size, 7-d culture was washed once with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Bacteria were then smeared, stained with acid-fast staining (Bai et al., 2009), and bacterial length of the microscopic images of 100 individual bacteria, which are 10 bacteria randomly selected in each of 10 fields, were analyzed with Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Detection of c-di-AMP

Bacteria were grown in Sauton’s broth (Bai et al., 2009) for 7 d and the OD600 of each strain was determined. Bacteria were then harvested and the supernatant was taken to determine secreted c-di-AMP. Each bacterial pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH8.0), heat-killed, and disrupted with 1 mm beads with a bead-beater (BioSpec). The lysate was collected, and the bacterial debris was removed by centrifugation for 10 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was used as bacterial c-di-AMP sample. The concentration of c-di-AMP was then determined using a competitive ELISA as we described previously (Bai et al., 2013, Bai et al., 2014).

Infection of macrophages and detection of IFN-β

Murine BMDMs of C57BL/6 and NOD2−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were generated as previously described (Jin et al., 2011). Bone marrow cells harvested from mouse femurs were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 20% FBS (BioSource International), 10% M-CSF–containing media, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol. The medium was exchanged after 3 d, and cells were stained for the macrophage marker F4/80 at day 7.

Cells were seeded in 6-well or 12-well plates as specified. On the following day, the medium was exchanged with infection media with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) at 2:1, which was verified by plating dilutions on Middlebrook 7H10 plates to numerate colony-forming units (CFU) after 3 weeks of incubation. At 5 h post-infection, the supernatant was collected and filtered to determine IFN-β using the Verikine Mouse IFN-β ELISA kit (PBL Assay Science) per the manufacture’s manual. To determine intracellular bacterial CFU, cells were washed with PBS for three times and then lysed in 0.5% Triton and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (DOC) as previously described (Bai et al., 2011b). Serial dilutions of the lysate were plated onto Middlebrook 7H10 plates and CFU were enumerated after 3 weeks.

Infection of mice

This experiment was performed at Johns Hopkins Center for TB Research through an NIH contract. M. tuberculosis H37Rv WT, ΔcnpB, and the complemented mutant were grown in mycomedium. Female BALB/c mice at 4- to 5-week old were infected with an aerosol of M. tuberculosis culture using Glas-Col aerosol chambers by adjusting the inoculum to implant ~ 10,000 CFU in the lungs. At 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks post infection, 5 mice infected with each bacterial strain were euthanized at each time point to examine bacterial burden in the lungs and spleens, gross pathology, and tissue histology of the lungs. For bacterial burden, lungs and spleens were individually homogenized in sterile equipment. The homogenates were plated to enumerate CFU after 21 d of incubation. Additionally, 15 mice of each infected group were monitored daily for time-to-mortality until 220 d post-infection.

Sequence analyses, structural modeling, and statistics

Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW method of MegAlign (Lasergene). Protein structural modeling was performed using C3nD (Wang et al., 2000). A structural of T. thermophilus RecJ (PDB code 1IR6) (Yamagata et al., 2002) was used as template. Data of c-di-AMP levels, bacterial CFU, and IFN-β secretion were analyzed by a two-tailed t-test, except specified, using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). Survival rate of the infected mice was analyzed by Log-rank (Matel-Cox) test using Prism 5. P values of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The animal infection experiment was performed at Johns Hopkins Center for TB Research through an NIH contract HHSN27220100001. We thank Jeffery Cox for providing pJSC407, William Jacobs, Jr. for providing phAE159, and Hongmin Li for assistance of gel filtration. We are grateful to the Biochemistry Core of the Wadsworth Center for assistance of HPLC analysis. This project is partly supported by a Scientist Development Grant of the American Heart Associate 12SDG12080067 to GB and by Albany Medical College New Faculty Startup Funds to LJ.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Abdul-Sater AA, Tattoli I, Jin L, Grajkowski A, Levi A, Koller BH, Allen IC, Beaucage SL, Fitzgerald KA, Ting JP, Cambier JC, Girardin SE, Schindler C. Cyclic-di-GMP and cyclic-di-AMP activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:900–906. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal N, Lamichhane G, Gupta R, Nolan S, Bishai WR. Cyclic AMP intoxication of macrophages by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate cyclase. Nature. 2009;460:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature08123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Knapp GS, McDonough KA. Cyclic AMP signalling in mycobacteria: redirecting the conversation with a common currency. Cell Microbiol. 2011a;13:349–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Schaak DD, McDonough KA. cAMP levels within Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG increase upon infection of macrophages. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;55:68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Schaak DD, Smith EA, McDonough KA. Dysregulation of serine biosynthesis contributes to the growth defect of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis crp mutant. Mol Microbiol. 2011b;82:180–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Yang J, Eisele LE, Underwood AJ, Koestler BJ, Waters CM, Metzger DW, Bai G. Two DHH subfamily 1 proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae possess cyclic di-AMP phosphodiesterase activity and affect bacterial growth and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:5123–5132. doi: 10.1128/JB.00769-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Yang J, Zarrella TM, Zhang Y, Metzger DW, Bai G. Cyclic di-AMP impairs potassium uptake mediated by a cyclic di-AMP binding protein in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:614–623. doi: 10.1128/JB.01041-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Yang J, Zhou X, Ding X, Eisele LE, Bai G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv3586 (DacA) is a diadenylate cyclase that converts ATP or ADP into c-di-AMP. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Gretes M, Harlem C, Basuino L, Chambers HF. A mecA -negative strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with high-level beta-lactam resistance contains mutations in three genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4900–4902. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00594-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S, Bardarov Jr S, Jr, Pavelka Jr MS, Jr, Sambandamurthy V, Larsen M, Tufariello J, Chan J, Hatfull G, Jacobs Jr WR., Jr Specialized transduction: an efficient method for generating marked and unmarked targeted gene disruptions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3007–3017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JR, Koestler BJ, Carpenter VK, Burdette DL, Waters CM, Vance RE, Valdivia RH. STING-Dependent Recognition of Cyclic di-AMP Mediates Type I Interferon Responses during Chlamydia trachomatis Infection. MBio. 2013;4:e00018–e00013. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00018-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MP, Graham CM, McNab FW, Xu Z, Bloch SA, Oni T, Wilkinson KA, Banchereau R, Skinner J, Wilkinson RJ, Quinn C, Blankenship D, Dhawan R, Cush JJ, Mejias A, Ramilo O, Kon OM, Pascual V, Banchereau J, Chaussabel D, O'Garra A. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 2010;466:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrov AG, Kirillina O, Ryjenkov DA, Waters CM, Price PA, Fetherston JD, Mack D, Goldman WE, Gomelsky M, Perry RD. Systematic analysis of cyclic di-GMP signalling enzymes and their role in biofilm formation and virulence in Yersinia pestis. Mol Microbiol. 2011;79:533–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie AG. Innate sensing of bacterial cyclic dinucleotides: more than just STING. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1137–1139. doi: 10.1038/ni.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. 2011;478:515–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chai Y, Guo JH, Losick R. Evidence for cyclic Di-GMP-mediated signaling in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:5080–5090. doi: 10.1128/JB.01092-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KH, Kang SO. Streptococcus pyogenes c-di-AMP Phosphodiesterase, GdpP, Influences SpeB Processing and Virulence. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan RM, Abbott JC, Burhenne H, Kaever V, Grundling A. c-di-AMP Is a New Second Messenger in Staphylococcus aureus with a Role in Controlling Cell Size and Envelope Stress. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan RM, Campeotto I, Jeganathan T, Roelofs KG, Lee VT, Grundling A. Systematic identification of conserved bacterial c-di-AMP receptor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9084–9089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300595110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan RM, Grundling A. Cyclic di-AMP: another second messenger enters the fray. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:513–524. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cron LE, Stol K, Burghout P, van Selm S, Simonetti ER, Bootsma HJ, Hermans PW. Two DHH subfamily 1 proteins contribute to pneumococcal virulence and confer protection against pneumococcal disease. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3697–3710. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01383-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvignes L, Wolf AJ, Ernst JD. Dynamic roles of type I and type II IFNs in early infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2012;188:6205–6215. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey B, Cheung L, Pokkali S, Guo H, Lee JH, Bishai WR. Keystone Symposium - Host Response in Tuberculosis. British Columbia, Canada: Whisterler; 2013. Mar 13–18, Cyclic-di-AMP mediated modulation of type-1 and type-2 IFN response dictates the fate of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. [Google Scholar]

- El Qaidi S, Yang J, Zhang JR, Metzger DW, Bai G. The vitamin B6 biosynthesis pathway in Streptococcus pneumoniae is controlled by pyridoxal 5'-phosphate and the transcription factor PdxR and has an impact on ear infection. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:2187–2196. doi: 10.1128/JB.00041-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florczyk MA, McCue LA, Purkayastha A, Currenti E, Wolin MJ, McDonough KA. A family of acr-coregulated Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes shares a common DNA motif and requires Rv3133c (dosR or devR) for expression. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5332–5343. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5332-5343.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Mukherjee S, Matthews PM, Hammad LA, Kearns DB, Dann CE., 3rd Functional characterization of core components of the Bacillus subtilis c-di-GMP signaling pathway. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:4782–4792. doi: 10.1128/JB.00373-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths JM, O'Neill AJ. Loss of function of the GdpP protein leads to joint beta-lactam/glycopeptide tolerance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:579–581. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05148-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundner C, Cox JS, Alber T. Protein tyrosine phosphatase PtpA is not required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth in mice. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;287:181–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K, Kumar P, Chatterji D. Identification, activity and disulfide connectivity of C-di-GMP regulating proteins in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Hill KK, Filak H, Mogan J, Knowles H, Zhang B, Perraud AL, Cambier JC, Lenz LL. MPYS is required for IFN response factor 3 activation and type I IFN production in the response of cultured phagocytes to bacterial second messengers cyclic-di-AMP and cyclic-di-GMP. J Immunol. 2011;187:2595–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppetipola N, Shuman S. A phosphate-binding histidine of binuclear metallophosphodiesterase enzymes is a determinant of 2',3'-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30942–30949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805064200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyoun JJ. A Note on Uhlenhuths Method for Sputum Examination, for Tubercle Bacilli. Am J Public Health (N Y) 1915;5:867–870. doi: 10.2105/ajph.5.9.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulasakara H, Lee V, Brencic A, Liberati N, Urbach J, Miyata S, Lee DG, Neely AN, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Ausubel FM, Lory S. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3'-5')-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2839–2844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Helmann JD. Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis sigma(M) in beta-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol Microbiol. 2012;83:623–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikandan K, Sabareesh V, Singh N, Saigal K, Mechold U, Sinha KM. Two-step synthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic di-AMP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanillo PS, Shiloh MU, Portnoy DA, Cox JS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates the DNA-dependent cytosolic surveillance pathway within macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue LA, McDonough KA, Lawrence CE. Functional classification of cNMP-binding proteins and nucleotide cyclases with implications for novel regulatory pathways in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Genome Res. 2000;10:204–219. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough KA, Rodriguez A. The myriad roles of cyclic AMP in microbial pathogens: from signal to sword. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;10:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehne FM, Gunka K, Eilers H, Herzberg C, Kaever V, Stulke J. Cyclic di-AMP homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis : both lack and high-level accumulation of the nucleotide are detrimental for cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2004–2017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JW, Sudarsan N, Furukawa K, Weinberg Z, Wang JX, Breaker RR. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger c-di-AMP. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:834–839. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey AK, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Fortune SM, Coulombe F, Behr MA, Fitzgerald KA, Sassetti CM, Kelliher MA. NOD2, RIP2 and IRF5 play a critical role in the type I interferon response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000500. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvatiyar K, Zhang Z, Teles RM, Ouyang S, Jiang Y, Iyer SS, Zaver SA, Schenk M, Zeng S, Zhong W, Liu ZJ, Modlin RL, Liu YJ, Cheng G. The helicase DDX41 recognizes the bacterial secondary messengers cyclic di-GMP and cyclic di-AMP to activate a type I interferon immune response. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/ni.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podobnik M, Tyagi R, Matange N, Dermol U, Gupta AK, Mattoo R, Seshadri K, Visweswariah SS. A mycobacterial cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase that moonlights as a modifier of cell wall permeability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32846–32857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.049635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postic G, Danchin A, Mechold U. Characterization of NrnA homologs from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Rna. 2012;18:155–165. doi: 10.1261/rna.029132.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi C, Waters EM, Rudkin JK, Schaeffer CR, Lohan AJ, Tong P, Loftus BJ, Pier GB, Fey PD, Massey RC, O'Gara JP. Methicillin resistance alters the biofilm phenotype and attenuates virulence in Staphylococcus aureus device-associated infections. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002626. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao F, See RY, Zhang D, Toh DC, Ji Q, Liang ZX. YybT is a signaling protein that contains a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase domain and a GGDEF domain with ATPase activity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:473–482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romling U. Great times for small molecules: c-di-AMP, a second messenger candidate in Bacteria and Archaea. Sci Signal. 2008;1:pe39. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.133pe39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RP, Lucey J, O'Donovan K, McCarthy Y, Yang L, Tolker-Nielsen T, Dow JM. HD-GYP domain proteins regulate biofilm formation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer JD, Sotelo-Troha K, von Moltke J, Monroe KM, Rae CS, Brubaker SW, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Woodward JJ, Portnoy DA, Vance RE. The N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced Goldenticket mouse mutant reveals an essential function of Sting in the in vivo interferon response to Listeria monocytogenes and cyclic dinucleotides. Infect Immun. 2011;79:688–694. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00999-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz KT, Carleton JD, Quillin SJ, Rollins SD, Portnoy DA, Leber JH. Hyperinduction of host beta interferon by a Listeria monocytogenes strain naturally overexpressing the multidrug efflux pump MdrT. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1537–1545. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06286-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. Mycobacterial adenylyl cyclases: biochemical diversity and structural plasticity. FEBS Lett. 2006a;580:3344–3352. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy AR, Visweswariah SS. New messages from old messengers: cAMP and mycobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2006b;14:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WM, Pham TH, Lei L, Dou J, Soomro AH, Beatson SA, Dykes GA, Turner MS. Heat resistance and salt hypersensitivity in Lactococcus lactis due to spontaneous mutation of llmg_1816 (gdpP) induced by high-temperature growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7753–7759. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02316-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SA, Johndrow JE, Manzanillo P, Cox JS. The Type I IFN response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires ESX-1-mediated secretion and contributes to pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2007;178:3143–3152. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultan SZ, Pitzer JE, Miller MR, Motaleb MA. Analysis of a Borrelia burgdorferi phosphodiesterase demonstrates a role for cyclic-di-guanosine monophosphate in motility and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2010;77:128–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo R, Schild S, Pratt JT, Camilli A. Role of cyclic Di-GMP during el tor biotype Vibrio cholerae infection: characterization of the in vivo-induced cyclic Di-GMP phosphodiesterase CdpA. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1617–1627. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01337-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teles RM, Graeber TG, Krutzik SR, Montoya D, Schenk M, Lee DJ, Komisopoulou E, Kelly-Scumpia K, Chun R, Iyer SS, Sarno EN, Rea TH, Hewison M, Adams JS, Popper SJ, Relman DA, Stenger S, Bloom BR, Cheng G, Modlin RL. Type I interferon suppresses type II interferon-triggered human anti-mycobacterial responses. Science. 2013;339:1448–1453. doi: 10.1126/science.1233665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate regulates Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5873–5882. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5873-5882.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufariello JM, Jacobs WR, Jr, Chan J. Individual Mycobacterium tuberculosis resuscitation-promoting factor homologues are dispensable for growth in vitro and in vivo. Infect Immun. 2004;72:515–526. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.515-526.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcheze C, Av-Gay Y, Attarian R, Liu Z, Hazbon MH, Colangeli R, Chen B, Liu W, Alland D, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR., Jr Mycothiol biosynthesis is essential for ethionamide susceptibility in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:1316–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Geer LY, Chappey C, Kans JA, Bryant SH. Cn3D: sequence and structure views for Entrez. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:300–302. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte CE, Whiteley AT, Burke TP, Sauer JD, Portnoy DA, Woodward JJ. Cyclic di-AMP Is Critical for Listeria monocytogenes Growth, Cell Wall Homeostasis, and Establishment of Infection. MBio. 2013;4:e00282–e00213. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00282-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte G, Hartung S, Buttner K, Hopfner KP. Structural biochemistry of a bacterial checkpoint protein reveals diadenylate cyclase activity regulated by DNA recombination intermediates. Mol Cell. 2008;30:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science. 2010;328:1703–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1189801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata A, Kakuta Y, Masui R, Fukuyama K. The crystal structure of exonuclease RecJ bound to Mn2+ ion suggests how its characteristic motifs are involved in exonuclease activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5908–5912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092547099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Hara H, Tsuchiya K, Sakai S, Fang R, Matsuura M, Nomura T, Sato F, Mitsuyama M, Kawamura I. Listeria monocytogenes strain-specific impairment of the TetR regulator underlies the drastic increase in cyclic di-AMP secretion and beta interferon-inducing ability. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2323–2332. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06162-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, He ZG. Radiation-sensitive gene A (RadA) targets DisA, DNA integrity scanning protein. A to negatively affect its cyclic-di-AMP synthesis activity in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22426–22436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.464883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li W, He ZG. DarR, a TetR-like transcriptional factor, is a cyclic-di-AMP responsive repressor in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3085–3096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.428110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]