Abstract

Antibodies can have a protective but non-essential role in natural chlamydial infections dependent on antigen specificity and antibody isotype. IgG is the dominant antibody in both male and female reproductive tract mucosal secretions, and is bi-directionally trafficked across epithelia by the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). Using pH-polarized epididymal epithelia grown on Transwells, IgG specifically targeted at an extracellular chlamydial antigen; the major outer membrane protein (MOMP), enhanced uptake and translocation of infection at pH 6–6.5 but not at neutral pH. This was dependent on FcRn expression. Conversely, FcRn-mediated transport of IgG targeting the intracellular chlamydial inclusion membrane protein A (IncA), induced aberrant inclusion morphology, recruited autophagic proteins independent of lysosomes and significantly reduced infection. Challenge of female mice with MOMP-specific IgG-opsonized Chlamydia muridarum delayed infection clearance but exacerbated oviduct occlusion. In male mice, MOMP-IgG elicited by immunization afforded no protection against testicular chlamydial infection, whereas the transcytosis of IncA-IgG significantly reduced testicular chlamydial burden. Together these data show that the protective and pathological effects of IgG are dependent on FcRn-mediated transport as well as the specificity of IgG for intracellular or extracellular antigens.

Keywords: IgG, Chlamydia, FcRn, vaccine

Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections affect an estimated 106 million people annually.1 Infections are often asymptomatic (30–50% male patients, 70–90% female patients2), leading to undiagnosed and untreated epidemics. In female patients, C. trachomatis commonly infects the endocervix, leading to an ascending infection that can cause pelvic inflammatory disease in an estimated 30% of patients, with 10–20% of pelvic inflammatory disease patients progressing to tubal infertility.3 Similarly in male patients, chlamydial infection of the penile urethra can ascend to colonize the prostate, epididymes and testes leading to inflammation, pathology and potentially infertility.4 CD4+ T helper (Th) 1 cells secreting interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha are known to be crucial in clearance of chlamydial infection,5 yet this phenotype of T cells are known to breakdown immune privilege in the testes, leading to autoimmunity against sperm resulting in infertility.6 Thus, the conventional approach to vaccine development in female patients (inducing potent Th1 responses) may promote infertility in male patients, making antibodies an attractive alternative. As a widely used model of human C. trachomatis infections, vaginal or penile infection of mice with C. muridarum, leads to an ascending infection and upper reproductive tract sequelae7 that closely mimics the human immunopathology.8

C. trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium with a biphasic life cycle consisting of an extracellular elementary body (EB) phase, and an intracellular replicative reticulate body (RB) phase. The EB is resistant to environmental and physical disruptions despite having no detectable peptidoglycan, but is stabilized with highly cross-linked disulfide-bonded proteins in the outer membrane (primarily major outer membrane protein (MOMP)).9 Following attachment and infection of the host cell, the EB differentiates into a reticulate body within a non-fusogenic parasitophorous vacuole termed an inclusion, which is made up of at least 22 inclusion membrane proteins (for example, IncA).10 Within the inclusion, reticulate bodies acquire host nutrients and replicate while also secreting proteases (for example, Chlamydia protease-like activity factor (CPAF)) into the host cell cytosol. After 72 h of infection most reticulate bodies have differentiated back into the EB phase and are then released from the cell by extrusion or lysis allowing further infection. In the context of a vaccine, temporal expression of chlamydial antigens across the spectrum of the life cycle offer the potential to prevent host cell attachment, and arrest intracellular replication.

Antibodies are arguably the first line of defense against infection and are responsible for the sterilizing immunity elicited by the most successful vaccines. However, the role of antibodies in urogenital chlamydial infections remains controversial. Although IgG and Fc gamma receptors (FcγR) appear to have a pivotal role in acquired immunity against Chlamydia,11–13 EB opsonization by IgG has also been shown to enhance chlamydial uptake and infection of cells with mouse IgG2b and mouse FcγRII,14 and also mouse IgG3 and human FcγRIII.15 Thus there appears to be contrasting roles for IgG targeting extracellular EB antigens (specifically MOMP) in vitro and in vivo. More importantly, the trafficking of these potential enhancing/ neutralizing antibodies has received minimal research interest.

The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) is ubiquitously expressed throughout the mucosal tissues of mammals on antigen-presenting cells, syncytiotrophoblasts, endothelial and epithelial cells.16 FcRn is a MHC-I (major histocompatibility complex class I)-like IgG transporter that requires dimerization with beta-2 microglobulin (β2m) to function.17,18 FcRn reversibly binds IgG between domains CH2–CH3 under acidic conditions (pH 5–6.5) and releases at neutral pH (pH 7.4).16 Therefore, FcRn facilitates bidirectional IgG delivery in and out of the lumen of the male and female reproductive tracts in a pH-dependent manner.19,20 FcRn can also increase the half-life of bound ligands (IgG and albumin) in vivo,18 translocate IgG-bound antigen through epithelial cells for delivery to antigen-presenting cells,21 and intraepithelial IgG can also bind and eliminate internalized virus.22 As FcRn binds IgG at acidic pH and is expressed by reproductive tract epithelia (vagina, uterus, epididymes and prostate) all of which have an acidic luminal pH, IgG specific for chlamydial extracellular antigens may increase infectivity by enhancing the uptake of IgG-opsonized Chlamydia. Conversely, FcRn-bound IgG specific for chlamydial intracellular antigens could potentially target internalized Chlamydia for degradation. In this study, we sought to determine the role of FcRn and IgG targeting intracellular and extracellular chlamydial antigens on infection outcomes at an acidic pH similar to that of both the male and female reproductive tracts.

RESULTS

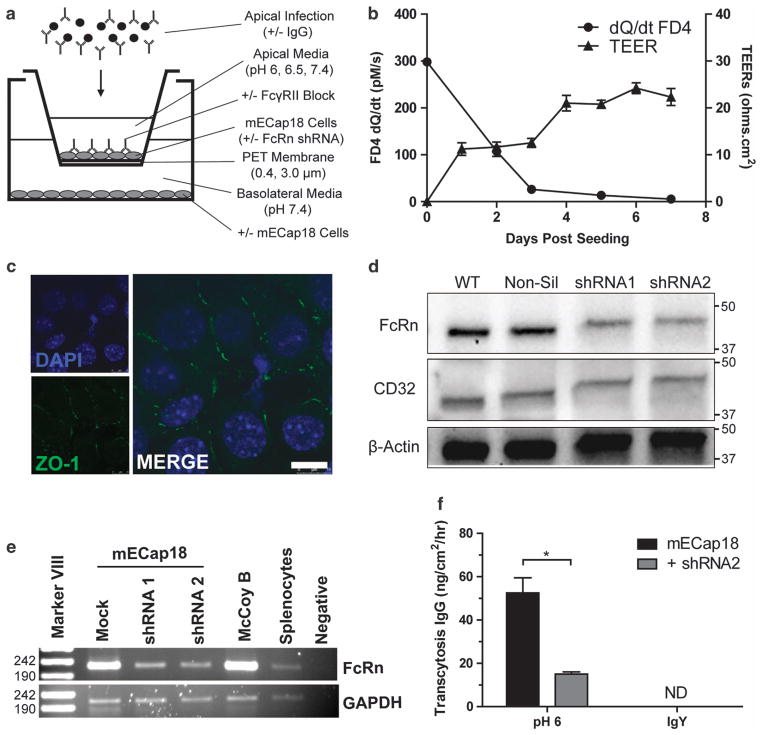

Characterization and silencing of FcRn in mECap18 cells

The mECap18 cells seeded on Transwell inserts were found to have low transepithelial electrical resistances, but were able to prevent passive flux of 4 kDa FITC dextran by 95% after 5 days and 98% by day 7 (Figure 1b). To confirm epithelial tight junction formation, cells grown on Transwells for 5 days were probed for ZO-1 expression (Figure 1c). After 5 days, mECap18 cells had visible ZO-1 protein expression at cell–cell barriers. Untreated mECap18 cells were found to constitutively transcribe both FcRn (4.5 × 10−2 relative copies to β2 m) and FcγRII (4.4 × 10−4 relative copies to β2 m) with no detectable FcγRI or FcγRIII mRNA by qRT–PCR (not shown). Protein expression of FcγRII and FcRn was confirmed by western blot (Figure 1d). Following transfection with shRNA targeting FcRn mRNA, mECap18 cells were found to downregulate FcRn mRNA transcription by PCR (Figure 1e), and FcRn protein expression by western blot (Figure 1d). Silencing of FcRn expression caused a significant 72% decrease in IgG transcytosis (P<0.05) (Figure 1f).

Figure 1.

Characterization and silencing of FcRn in epididymal epithelial cells. (a) Experimental system used throughout this study. (b) Passive apical to basolateral flux of FITC dextran (FD4) over 2 h, and transepithelial electrical resistances over time was determined for mECap18 cells grown on 0.4 μm Transwell inserts. (c) Tight junction protein ZO-1 expression by mECap18s grown for 5 days on a Transwell inserts was determined by anti-ZO-1 antibody and observed with an SP5 confocal microscope. (d) mECap18 cells were transfected with a shRNA FcRn mRNA silencing vector and clones screened by western blot using anti-FcRn, anti-CD16/32 and β-actin antibodies. (e) mECap18 cells transfected with non-silencing (Mock), or FcRn silencing shRNA1 (#58263) or shRNA2 (#43474) were analyzed for transcripts of FcRn and GAPDH mRNA by qRTPCR. Murine fibroblasts (McCoy B) and female BALB/c splenocytes were used as positive controls. Image shows agarose electrophoresis following qRT–PCR quantification. (f) Apical to basolateral transcytosis of murine IgG or chicken IgY was determined by growing mECap18 (+ / − shRNA2) for 5 days and adding antibody apically, and measuring the amount of antibody detected in the basolateral chamber after 2 h. Statistical significance determined with Student’s t-test (n = 3–5 wells per condition). All results representative of at least two individual experiments. Scale bar, 10 μm. Error bars indicative of mean±s.e.m.

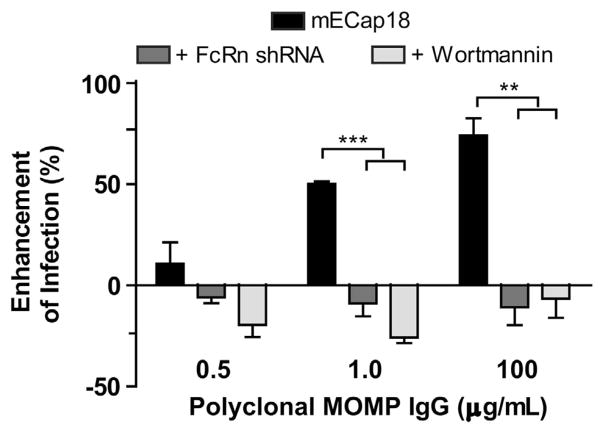

FcRn-mediated uptake and translocation of IgG-opsonized Chlamydia

To determine if polyclonal anti-MOMP IgG neutralized or enhanced infection under polarizing conditions, mECap18 cells (+/− shRNA FcRn) were grown on Transwell inserts for 5 days, and then apically infected with EBs opsonized with increasing concentrations of MOMP-IgG. The pH of the apical medium was adjusted to 6.5 to replicate in vivo epididymal lumen conditions.23 Non-silenced cells were also treated with wortmannin to chemically inhibit FcγRII/FcRn-mediated enhancement of infection.14,24 There was an IgG dose-dependent enhancement of infection of MOMP-IgG-opsonized EBs (MOMP-IgG:EBs) (P<0.01) (Figure 2). EBs treated with 1 μg ml−1 of polyclonal MOMP IgG demonstrated a 50% enhancement of infection (P<0.001), and EBs opsonized with 100 μg ml−1 enhanced infection by 74% (P<0.01). This enhancement of infection was abrogated in shRNA-transfected or wortmannin-treated mECap18 cells. The purified MOMP-IgG contained antigen-specific IgG of all subclasses with the majority of the EB-binding activity seen in IgG1 and IgG2b subclasses (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2.

FcRn-mediates enhancement of infection via uptake of IgG-opsonized EBs. mECap18 cells (mock or FcRn shRNA) were grown on 0.4 μm Transwell inserts for 5 days and then apically infected with media at pH 6.5 containing EBs pre-incubated with varying concentrations of polyclonal MOMP-IgG. Enhancement of infection was determined by comparison with wells infected with EBs pre-incubated with 100 μg ml−1 polyclonal OVA-IgG. IFUs were enumerated by fluorescence microscopy. Groups run in triplicate insert/wells per group. Results are representative of five individual experiments. Statistics determined with Student’s t-test. Error bars indicate mean±s.e.m.

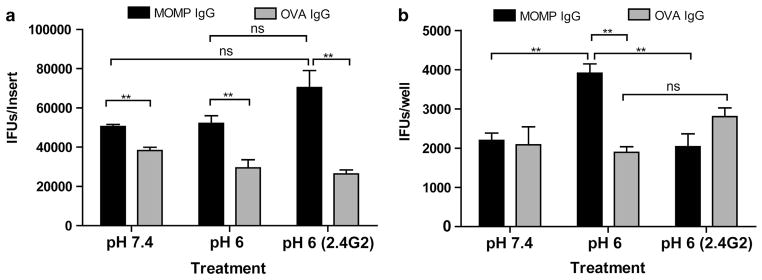

Translocation of IgG-opsonized chlamydial EBs

Having shown that MOMP-IgG enhanced infection of pH-polarized epithelial cells, and transcytosis of IgG:OVA immune complexes (ICs) across epithelia has previously been demonstrated,21 we sought to determine if epithelial cells could traffic IgG:EB ICs from the apical to the basolateral chamber where they could infect other cells. As chlamydial EBs are ~0.31–0.44 μm in size,25 we seeded mECap18 cells onto 3.0 μm inserts. Infection of mECap18 cells grown on the insert membrane was enhanced by IgG-opsonization of EBs by 77% at pH 6, increasing to 167% (P<0.01) when FcγRII was blocked with 2.4G2 (Figure 3a). When observing basolateral infection, a significant increase in infection (106%, P<0.01) was observed only in basolateral wells with apical inserts infected at pH 6, but not blocked with 2.4G2. Similar results were observed when seeding murine macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) in the basolateral chamber (not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that IgG (IgG1 or IgG2b) targeting extracellularly exposed domains of the chlamydial EB can enhance binding and uptake of infectious particles by FcγRII and FcRn. When both receptors are chemically inhibited with wortmannin or FcRn expression alone was silenced, the enhancement of infection was abrogated, yet when FcγRII was blocked the translocation of opsonized EBs was significantly reduced suggesting FcγRII may load FcRn with IgG:IC and direct it for basolateral trafficking.

Figure 3.

FcRn transcytosis of IgG opsonized EBs facilitates translocation of infection. mECap18 cells were grown on 3 μm Transwell inserts for 5 days and infected with EBs pre-incubated with polyclonal MOMP or OVA IgG. Cells were apically infected under neutral pH (7.4), or acidic pH (6) with or without CD32-blocking antibody (2.4G2). (a) IFUs quantified in cells in the apical epithelia. (b) IFUs quantified in the basolateral epithelia following translocation. IFUs were determined by fluorescence microscopy. Groups run in triplicate insert/wells per group. Results representative of three repeat experiments. Statistics determined with Student’s t-test. Error bars indicate mean±s.e.m.

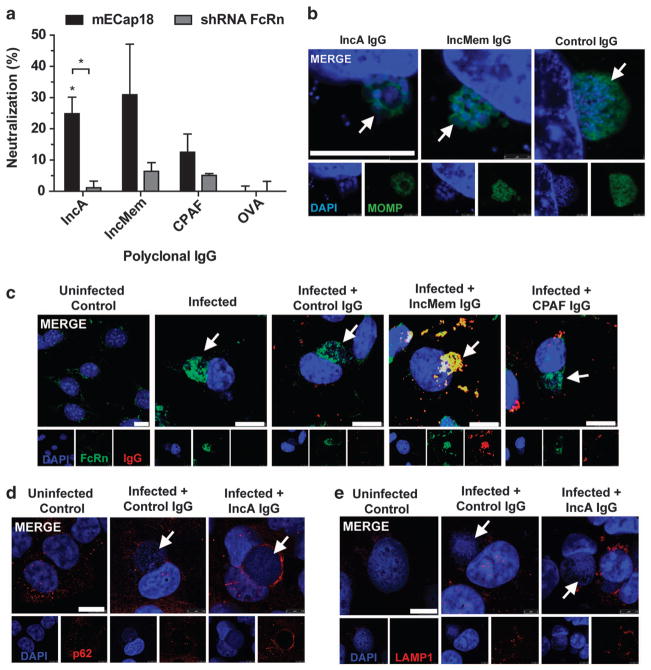

FcRn internalized IgG can bind and neutralize intracellular Chlamydia

Following infection of polarized mECap18 cells, polyclonal IgG from mice immunized with IncA, IncMem, CPAF or OVA was added to both apical and basolateral media and inclusion forming unit (IFU) determined after 24 h (Figure 4a). IncA-IgG provided significant partial protection (25%; P<0.05), in an FcRn-dependent manner (P<0.05). IgG targeting inclusion membrane lysates (IncMem) or secreted protease CPAF failed to provide significant protection against infection compared with OVA-IgG controls. When observing chla-mydial inclusions by microscopy, both IncA/IncMem IgG-treated cells exhibited aberrant inclusion formation (Figure 4b), consistent with microinjection of polyclonal anti-IncA IgG into cells.26 We also confirmed that Chlamydia muridarum begins expressing detectable IncA at 7–8 h post infection using the mouse IncA IgG and anti-mouse-IgG-AlexaFluor568 (not shown). Only internalized FcRn and inclusion-specific IgG were found to co-localize at the inclusion membrane (Figure 4c). Interestingly however, infection caused FcRn to be internalized and accumulate at the inclusion regardless of the addition of IgG. Further investigation found that accumulation occurred between 6–8 h post infection (Supplementary Figure 2A), was Chlamydia-mediated and required an intact microtubule network (Supplementary Figure 2B). This accumulation was also observed in human epithelial cells infected with C. trachomatis serovars D and L2 (Supplementary Figure 2C), or C. pneumoniae AR39 (not shown). FcRn-mediated IncA-IgG neutralization was found to be associated with accumulation of sequestosomal protein p62 (Figure 4d), and independent of lysosomal activation (Figure 4e).

Figure 4.

FcRn internalized IgG binds chlamydial antigens reducing growth and mediating sequestasomal activation. (a) Epididymal cells were grown on Transwells for 5 days, apically infected with C. muridarum for 3–4 h and replaced with fresh apical media (pH 6.5) and basolateral media (pH 7.4) containing polyclonal IgG (100 μg ml−1) purified from IncA, IncMem, CPAF or OVA immunized mice for a further 20 h. Neutralization was determined relative to the mean OVA-IgG controls. (b–e) mECap18 cells grown on coverslips overnight, and infected for 24 h with media containing various antigen-specific IgG fixed and stained for fluorescence microscopy. (b) Aberrant inclusion formation, (c) colocalization of IgG and FcRn with Chlamydia inclusion, (d) sequestosome (p62) and (e) lysosomal (LAMP1) localization. Results representative of two to three individual experiments. White arrows identify chlamydial inclusions. Statistics determined with Student’s t-test. Error bars indicate mean of triplicate wells ±s.e.m.

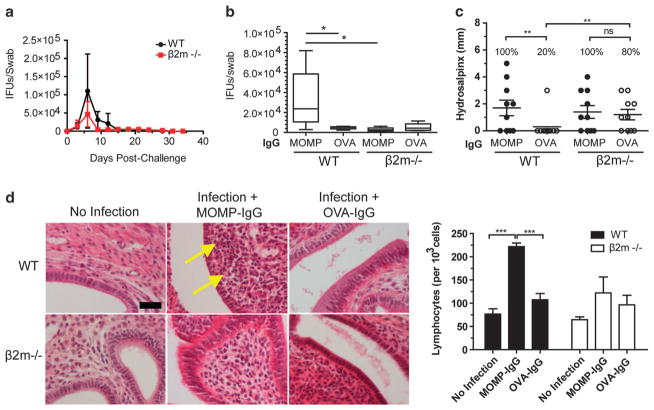

Infection of female mice with IgG-opsonized EBs delays recovery from infection and enhances pathology

To determine if enhancement or translocation of IgG-opsonized EBs occurred in vivo, female mice were infected with MOMP IgG:EBs, or OVA-IgG-treated EBs. Normal infection of wild-type (WT) and β2m−/− mice saw a peak of infection at day 6, which had resolved by day 24 (Figure 5a). There were no significant differences in vaginal shedding in any groups, until late in the infection (day 18) when initial MOMP-IgG opsonization of EBs extended the duration of infection (83% vs WT OVA-IgG infected; P<0.05) (Figure 5b). Interestingly, WT mice infected with MOMP-IgG:EBs had an 80% increase in hydrosalpinx incidence (P<0.05) and severity (P<0.01) (Figure 5c) despite not expressing FcRn,20 suggesting FcRn-translocation may exacerbate downstream immunopathological responses. WT mice infected with EBs coated in MOMP-IgG also had a twofold increase in intra-stromal lymphocytes in the uterine horns (P<0.001) (Figure 5d) compared with WT uninfected or OVA-IgG/EB infected mice. There were no significant differences in shedding or pathological outcomes in either group of β2m−/− mice, suggesting β2m and its heterodimers (FcRn, MHC-I and CD1) have a minimal role in reducing infectious burden but have an important role in protection from pathology.

Figure 5.

Infection with MOMP-IgG-opsonized EBs attenuates infection clearance, and enhances pathology in the murine FRT. WT and β2m−/− female mice were vaginally inoculated with 5 × 103 IFUs pre-incubated with MOMP IgG or OVA IgG. (a) Kinetics of vaginal shedding following challenge. (b) Cervicovaginal swab burden at late in infection (day 18). (c) Oviduct occlusion and dilation (hydrosalpinx) after 35 days of chlamydial challenge. Asterisks represent significant difference in total oviducts with hydrosalpinx (d). H&E staining of uterine horns following 35 days of infection. Images are representative of five separate mice. Arrows identify lymphocyte infiltration. Number of lymphocytes per 103 cells was determined by counting H&E sections. Scale bars, 50 μm. Statistics determined with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Transcytosis of IgG targeting intracellular, but not extracellular chlamydial antigens enhances protection in male mice

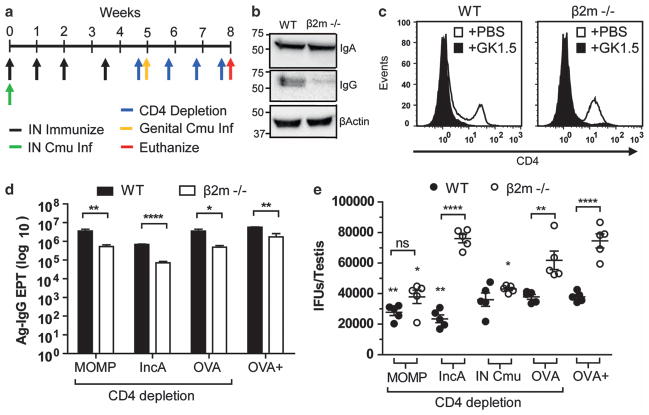

To determine the role of transcytosed IgG targeting extracellular and intracellular chlamydial antigens in vivo, WT and β2m−/− male C57BL/6 mice were utilized. Initially, intravenous and intraperitoneal passive immunization of purified IgG was trialled but only transient concentrations (peak 0.1 μg ml−1 6 h post immunization) reached the reproductive tract (not shown). To overcome this, we immunized male mice as done in the in vitro experiments as this schedule has previously been shown to produce reproductive tract IgG,27 but also depleted mice of CD4+ T cells to maximize the influence humoral responses on infection. CD4+ T cells were depleted both prior to challenge to eliminate immunization-acquired CD4+ T cells, and continuously throughout infection to prevent T-cell-dependent activation of infection-specific B cells.

Mice were intrasnasally immunized with MOMP, IncA or OVA, depleted of CD4+ T cells and urogenitally challenged with C. muridarum (Figure 6a). The inability of β2m−/− mice to transport IgG into tissues was validated by western blot of testes lysates (Figure 6b). To remove the protective role of CD4+ T cells in immunity, mice were continuously depleted of CD4+ T cells following immunization, and throughout urogenital infection with all GK1.5-treated groups having >90% reductions in CD4+ T cells at sacrifice (Figure 6c). All mice had serum antigen-specific IgA (Supplementary Figure 3) and IgG (Figure 6d) responses as determined by ELISA; however, all β2m−/− had a 1-log reduction in Ag-IgG (P<0.05) likely due to decreased IgG half-life.16,28 Following 3 weeks of infection, WT mice immunized with either MOMP or IncA had reductions of testicular chlamydial burden of 13% (P<0.01) and 33% (P<0.01), respectively, when compared with CD4-depleted OVA controls (Figure 6e). Immunization of β2m−/− mice with MOMP also provided a significant reduction in burden (38%; P<0.05) but this was not significantly different from MOMP-immunized WT mice (P>0.05). Interestingly, protection afforded from IncA immunization of WT mice was completely absent in β2m−/− (P<0.001). As naïve testicular infection of C57BL/6 male mice lasts at least 2 months (Supplementary Figure 4), and live respiratory infections are cleared within 2 weeks and have been shown to provide protection against genital challenge in female mice,29 some mice were also intranasally infected with C. muridarum prior to CD4-depletion and urogenital challenge. Recovery from respiratory infection as determined by cachexia was found to be supported by β2m expression (60% increase in recovery time of β2m−/− mice), but non-essential as all strains had recovered by day 15 (Supplementary Figure 5). Mice that had received a respiratory infection prior to challenge had no significant protection in the reproductive tract in the absence of CD4+ T cells; however, there was a 30% reduction in burden when comparing IN-infected to OVA-immunized β2m−/− mice. OVA-immunized, mock CD4-depleted (naïve response) showed no significant differences to OVA-immunized CD4-depleted mice (CD4-deficient naïve response) in either strain.

Figure 6.

Protection provided from antigen-specific IgG targeting intracellular chlamydial antigen, but not extracellular chlamydial antigen is dependent on functional FcRn. (a) Immunization and challenge schedule. (b) Homogenates of testes from naïve WT and β2m−/− mice were western blotted for IgA, IgG and β-actin. (c) Representative FACS blot of CD4+ T cells in the spleen at euthanasia. (d) Serum antigen-specific IgG endpoint titers of WT and β2m−/− mice immunized with corresponding antigen at euthanasia were determined by direct ELISA. (e) Viable chlamydial burden in the testes of immunized WT and β2m−/− mice after 3 weeks of infection was determined by cell culture and quantified by fluorescent microscopy. OVA-immunized, non-depleted control mice (OVA+). Statistics determined with Student’s t-test (d) and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc (e) (n =5). Asterisks above graph indicate group which is significantly different from OVA-immunized CD4-depleted group of the same strain. Dotted lines identify mean of OVA-immunized CD4-depleted WT and β2m−/− mice. Error bars indicate mean±s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

Antibody-mediated enhancement of chlamydial infections was first reported with HeLa 229 cells where a murine IgG3 monoclonal antibody enhanced uptake of EBs, facilitated by human FcγRIII.14,15 IgG2b opsonization of EBs also enhanced infection of Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with mouse FcγRII.14 However, neither HeLa nor Chinese hamster ovary cells express human FcRn,20,30 and would have poor affinity for mouse IgG even if present.20,31,32 Thus, we developed a model to investigate FcRn-mediated enhancement in mouse epithelial cells expressing FcγRII and FcRn. We report that in addition to FcγRII-mediated enhancement, IgG-opsonized chlamydiae can utilize FcRn to both gain entry in apical epithelia negating the neutralizing effects of IgG, but also transcytose across apically acidified epithelial cells where they can go onto infect pH-neutral basolateral cells (epithelial, fibroblasts and antigen-presenting cells). These data also suggest that epithelial FcγRII binding of IgG:IC may be priming FcRn to translocate IgG:IC as opposed to internalizing and in an effort to increase IgG half-life. This cooperation of FcγRs and FcRn has been shown to be important in neutrophil phagocytosis and cross presentation in DCs.33,34 Interestingly in female mice, enhancement of infection was not observed in terms of bacterial shedding in the vagina, but upper reproductive tract pathology was exacerbated in the uterine horns and oviducts simply by initially opsonizing EBs with MOMP-IgG prior to inoculation. There was a twofold increase of lymphocyte infiltrate in WT mice inoculated with MOMP-IgG:EBs compared with all other groups suggesting that functional FcRn may have translocated opsonized-EBs and exacerbated the immune response. Prior inoculation of WT mice with MOMP-IgG:EBs caused a significant increase in oviduct occlusion compared with OVA-IgG controls, but both β2m−/− groups had immunopathology demonstrating the vulnerability of β2m−/− mice to oviduct pathology, and makes enhancement of pathology due to MOMP-IgG:EBs difficult to interpret in this model. Regardless, the oviduct pathology was surprising as this tissue does not express FcRn,20 suggesting that a downstream response of FcRn translocation may be responsible for enhanced immunopathology. We are currently investigating whether the enhanced pathology in these mice may have been due to CD8-CD11b + dendritic cell uptake of IgG:IC and FcRn-mediated cross-presentation to CD8+ T cells,34 which are implicated in aggravated pathological sequelae during chlamydial infection of female mice.35 Owing to volume and physiological limitations in the male mouse model, we immunized and depleted of CD4+ T cells to remove the protective effect previously published.36 In male mice immunized with MOMP and depleted of CD4+ T cells, we saw a small 13% reduction in testicular burden, which was not dependent on the presence of IgG in the testes as there was no significant difference in the absence of functional FcRn and IgG. Together, this suggests a limited protective role for IgG targeting membrane proteins on the EB and that other mechanisms are providing protection in this environment, likely secretory IgA.27

Our in vitro Transwell data suggests that translocation of IgG-opsonized EBs to the sub-epithelia may be driving deleterious immunopathology in vivo. We recently reported similar findings showing enhanced pathology following infection with EBs pre-incubated with vaginal lavages from MOMP-immunized mice.37 MOMP is a multipass transmembrane protein that is a potent immunogenic antigen which induces robust cell-mediated and humoral responses during normal infections of both female and male mice, and is the most widely studied vaccine candidate.38 IgG specificity to specific domains of MOMP is also clinically used in C. trachomatis infections to differentiate serotypes. Thus, the potential for MOMP-IgG-mediated enhancement of infection is not limited to vaccination, but may also enhance infection/pathology following repeat infections, or in a primary infection contracted from a MOMP-IgG seropositive sexual partner. In support of increased risk of transmission, human male mice have been shown to have up to 24-fold more IgG in urethral secretions when infected with C. trachomatis.39 To expand on previous studies indentifying antibodies associated with upper reproductive tract pathology,40 it would be interesting to determine if IgG coating of EBs is a predictor for the outcome of pathological sequelae in female mice.

To determine the role IgG/FcRn in vivo, we used WT and β2m−/− mice which lack functional FcRn.17,18 Although the β2m−/− mice obviously have a deficit in all MHC class I-like proteins that may impact infection outcomes, the use of appropriate controls (control antigen, with or without CD4 depletion) should ameliorate concerns.

Although IgG and FcRn were found to enhance infection when targeting the extracellular antigen MOMP, we report that IgG targeting intracellular chlamydial proteins such as IncA was able to target the inclusion during FcRn-mediated transcytosis. We found that FcRn is recruited independent of IgG to the inclusion membrane along microtubules, between 6–8 h post infection and remains there for the rest of the infection. This is likely due to the recruitment of RabGTPases by Chlamydia spp. to the inclusion membrane.41 Although the chlamydial inclusion is traditionally considered non-fusogenic with the endocytic pathway,42 it obtains nutrients including sphingomyelin via fusion with exocytic trafficking vesicles, primarily using the host cell Rab4+ and Rab11+ GTPase pathways.41,43,44 Interestingly, both Rab4+ and Rab11+ are crucial in cellular trafficking of FcRn that may suggest why FcRn was detectable at the inclusion membrane.45 This Chlamydia-mediated accumulation of FcRn at the inclusion membrane may reduce the ability of IgG to transcytose and bind intracellular antigens later in the infection cycle.

Intracellular IgG was found to colocalize with FcRn, which together colocalized in the presence of IncA and IncMem IgG. We also show that the resulting IgG-bound inclusion exhibited aberrant morphology consistent with microinjection of anti-IncA IgG into infected cells identifying antigen-specific IgG and FcRn-dependent colocalization with the inclusion.26 Thus we confirm that IncA is cytoplasmic facing and can be bound by intracellular IgG, but also that normal cellular transport mechanism (that is, FcRn) can deliver IgG to the inclusion membrane where it can bind, block and enhance sequestosomal activity. Scidmore et al. have also reported that inclusion membrane proteins IncG, IncF and CT299 are cytoplasmic facing and can be bound by intracellular IgG, and that microinjection of CT229 antibodies into infected cells inhibits chlamydial infection.26,44 These three inclusion membrane proteins are also all expressed within 2 h of infection making them much more potent targets for intracellular IgG targeting as FcRn is not internalized to the inclusion membrane at this time.44,46 If high titers of anti-CT229 IgG could be achieved by vaccination, this may provide sterilizing immunity in reproductive tract tissues expressing FcRn.

Unlike FcRn-mediated clearance of internalized virus by IgG via lysosomal degradation,22 we did not observe LAMP1 aggregates, but rather observed colocalization of IgG, FcRn and the apoptosis/ ubiquitin proteosome marker p62. This is unsurprising as chlamydiae actively inhibit lysosomal fusion with the inclusion membrane as part of its normal growth,42 but the addition of IncA-IgG led to an accumulation of p62 at the inclusion membrane. Whether or not this was responsible for the reduction in growth requires further investigation.

Antibodies, and in particular IgG, are the principle reason many commercial vaccines are a success due to their high affinity for foreign antigens, long-lived production and both systemic and mucosal circulation. This makes IgG an interesting target in the development of a chlamydial vaccine, particularly in a male vaccine. Here we demonstrate that FcRn has a pivotal role on the outcome of IgG neutralization or enhancement of chlamydial infections, and more excitingly, that intracellular chlamydial antigens (inclusion membrane proteins and potentially other inclusion-secreted proteins) are viable candidates for a sub-unit chlamydial vaccine.

METHODS

Ethics statement

All experiments were performed with approval from the University Animal Ethics Committee (UAEC) of Queensland University of Technology (QUT) (UAEC #0800000824 and #0700000346).

Mice

Adolescent (>6 weeks) male and female C57BL/6 WT, and β2m−/− mice were used in these studies. Adolescent BALB/c male and female mice were also immunized and/or infected for production of antigen-specific IgG. WT C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from the Animal Resource Centre (Perth, Australia), and breeding pairs of C57BL/6 β2m−/− mice were generously donated by Prof. Mark Smyth (Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, East Melbourne, Australia). Mice were fed ad libitum with procedures performed under physical containment level 2 (PC2) conditions following NHMRC guidelines.

Cell lines and culture

C. muridarum (Weiss; ATCC VR-123) and McCoy B cells (ATCC CRL-1696) were purchased from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). C. muridarum were propagated in McCoy B cells and purified on a discontinuous Renografin gradient as described elsewhere.9 The hybridomas 2.4G2 and GK1.5 were generous gifts from Professor Graham Le Gros (Mallaghan Institute of Medical Research, Wellington, New Zealand). The SV40-immortalized murine caput epididymal epithelial (mECap18) cells were a generous gift from Dr Petra Sipila (Turku University, Turku, Finland),47 and were maintained in DMEM, 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin sulfate, 50 μg ml−1 gentamycin sulfate, 2 mM L-glutamine and 50 nM dihydrotestosterone as described elsewhere.47 An FcRn knockdown mECap18 clone was established by stable transfection with a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) pGIPZ vector targeting FcRn mRNA (Open Biosystems # V2LMM-43474) (Millennium Science, Surrey Hills, VIC, Australia). Positively transfected cells were selected for with 0.1 μg ml−1 puromycin. Clones were established by limiting dilution. Silencing of FcRn was determined by qRT-PCR on cDNA isolated from mECap18 cells, McCoy cells and splenocytes using PCR conditions of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 65 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s on a Rotorgene thermocycler (Qiagen, Chadstone, VIC, Australia). Exon-spanning primers for mouse FcRn (NM_010189) and mouse GAPDH (NM_008084.2) mRNA are listed (Supplementary Table 1). Western blotting was performing following transfer of cell lysates onto nitrocellulose and blocking with 5% skim milk PBS for 1 h. Blots were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse FcRn-cytoplasmic domain (purified from the sera of rabbits immunized with the cytoplasmic domain of murine FcRn), rat anti-mouse CD16/32 (2.4G2) or rabbit anti-β-actin (Abcam, Waterloo, VIC, Australia) for 1 h at room temperature, then washed and probed with corresponding secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP or goat anti-rat IgG heavy chain-HRP (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA)) for 1 h. Blots were washed with PBS, treated with ECL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Scoresby, VIC, Australia), and visualized with a Universal Hood II (Biorad, Gladesville, VIC, Australia).

Transwell assays

mECap18 cells (± pGIPZ shRNA FcRn) were seeded at 105 cells/insert onto 6.5 mm, 0.4 μm polyester Transwell inserts (BD Bioscience, North Ryde, NSW, Australia), and grown for 5 days, changing the media every second day (Figure 1a). The transepithelial electrical resistance was measured with an EVOM electrode (Millipore, Kilsyth, VIC, Australia). Electrical resistance was calculated from the formula: resistance of cells (ohms.cm2) = (resistance of cells—resistance of insert) × surface area of insert (cm2). Passive flux of FITC dextran (4 kDa) (FD4) was performed as described elsewhere.48 Zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) was observed in mECap18 cells grown on Transwell inserts for 5 days, fixed, blocked and probed with rabbit anti-ZO1 IgG (Invitrogen, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) for 1 h, and detected with goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). DNA was stained with DAPI (Invitrogen) for 20 min. Transcytosis of mouse IgG (polyclonal naïve purified IgG), or chicken IgY (Sigma Aldrich, Castle Hill, VIC, Australia) was determined on day 5 post-seeding as previously described.49 Briefly, 20 μg of polyclonal IgG or IgY was added to the apical chamber of pH-polarized mECap18 cells (apical pH 6.5, basolateral pH 7.4) and basolateral transport quantified after 2 h at 37 °C by sandwich ELISA.

Production of antigen-specific polyclonal IgG

Full-length recombinant C. muridarum MOMP was a generous gift from Dr Harlan Caldwell (Rocky Mountain Labs, Hamilton, MT, USA) and was expressed and purified as previously described.50 Lyophilized control antigen OVA was purchased (Sigma Aldrich) and resuspended in PBS. Full-length recombinant C. muridarum IncA (NP_296774) and CPAF (NP_296627) were produced by amplifying full-length coding sequences with primers (Supplementary Table 1) using Pfu polymerase (Promega, Alexandria, NSW, Australia) and hotstart PCR conditions of 95 °C for 2 min, addition of Pfu polymerase, then 35 cycles of 95 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min and 74 °C for 5 min. Amplicons were purified using Purelink PCR purification columns (Invitrogen) and restriction digested with BamHI/EcoRI (IncA) or BamHI/KpnI (CPAF) for 1 h at 37 °C. Digested amplicons were ligated using T4 DNA Ligase (Promega) into the N′ terminal his-tag vector pRSET-A (Invitrogen) previously restriction digested with corresponding restriction enzymes. Vectors were transformed into BL21 (DE3) pLysS Escherichia coli (Invitrogen), grown to OD600 nm = 0.4 and induced with 0.5 μM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside for 3 h at 30 °C. E. coli was lysed and His-tagged protein purified using Talon affinity resin (Clontech, Clayton, VIC, Australia) as per the manufacturers’ instructions. Proteins were eluted with 150 mM imidazole and dialysed into PBS and stored at −80 °C. Inclusion membrane lysates (IncMem) from McCoy B cells infected for 24 h with C. muridarum were semi-purified by centrifugation as previously described.51 Mice were intranasally immunized with 20 μg of antigen, 2.5 μg of cholera toxin (CT) (Sapphire Bioscience, Waterloo, NSW, Australia) and 10 μg of CpG-ODN (Sigma Aldrich) on day 0, 7, 14 and 25. Serum was collected on day 35 and polyclonal IgG purified using Protein G resin (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified IgG was stored in PBS at −80 °C until required.

In vitro enhancement or neutralization of infection

In vitro neutralization was determined from the formula: neutralization (%) = 100 − ((IFUs per well/average IFUs of OVA controls) × 100). Enhancement of infection was determined as negative neutralization. mECap18 (+ / − shRNA FcRn) were grown on Transwell inserts for 5 days, serum starved in HBSS pH buffered to 7.4 with 30 mM HEPES (HBSS + 7.4) for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then pH-polarized for 30 min at 37 °C by incubating cells with HBSS + 7.4 in the basolateral chamber, and HBSS buffered to pH 6.5 with 30 mM MES (HBSS + 6.5) in the apical chamber. At this point, some non-transfected mECap18 cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 150 nM wortmannin (Sigma Aldrich) to inhibit both FcRn and FcγRII-mediated endocytosis.14,24,52 Purified IgG at various concentrations were incubated with 5 × 104 IFUs of C. muridarum in HBSS + 6.5 for 1 h at 4 °C to allow opsonization. The pH-polarized cells were then apically infected for 4 h at 37 °C. HBSS media was then removed, and replaced with growth media for 20 h (total 24 h infection) before fixation with methanol, and IFUs enumeration by fluorescence microscopy using sheep anti-Cmu MOMP sera as previously described53 For intracellular IgG neutralizations, mECap18 cells (+ / − shRNA) were grown for 5 days and then infected with 105 IFUs at 37 °C for 1 h. Fresh media (apical pH 6.5, basolateral pH 7.4) containing 100 μg ml−1 purified mouse IgG (IncA, IncMem, CPAF or OVA-specific mouse IgG) was then added. After 24 h of infections, cells were fixed with methanol and IFUs enumerated as above. For co-localization experiments, fixed cells were blocked with 5% FCS in PBS for 1 h, and probed with rabbit anti-mouse IgG-AlexaFluor568 (Invitrogen), rabbit anti-mouse FcRn-CT, followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG-AlexaFluor488 (Invitrogen); or rabbit anti-LAMP1 (Abcam) or rabbit anti-SQSTM1(p62) (Abcam) and detected with goat anti-rabbit IgG-AlexaFluor568 (Invitrogen). Coverslips were then incubated in DAPI (Invitrogen) for 20 min, and mounted onto glass slides with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) overnight. Coverslips were imaged with an SP5 confocal microscope (Leica, North Ryde, NSW, Australia).

Translocation of opsonized EBs

As opsonization of EBs with MOMP-IgG enhanced apical infection, we sought to determine if IgG-opsonized EBs (0.3–0.45 μm in size) could also be translocated across the monolayer to the basolateral chamber. mECap18 cells were seeded onto 3.0 μm Transwell inserts for 5 days. On day 3, 105 mECap18 cells were also seeded into each basolateral chamber of 24-well Transwell plates. On day 5, cells were serum starved and pH-polarized as described above. EBs were incubated with 100 μg IgG/105 EBs in HBSS + 6 or HBSS + 7.4 for 1 h at 4 °C to allow opsonization. Prior to infection, some inserts were apically treated with 2 μg ml−1 2.4G2 in HBSS + 7.4 for 30 min at 4 °C to allow FcγRII blocking. Unbound antibody was then washed away with ice-cold HBSS + 7.4, and cells re-incubated in HBSS + 6 for 15 min at 37 °C. Inserts were then apically infected for 4 h at 37 °C with IgG-treated EBs, in HBSS + 7.4, HBSS + 6 or HBSS + 6/2.4G2 block. HBSS was then discarded, and replaced with growth media for an additional 20 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, cells on the inserts and in the basolateral chambers were washed, fixed and IFUs quantified by fluorescent microscopy.

Chlamydial infection of mice

Male C57BL/6 WT and β2 m−/− mice were intranasally immunized with MOMP, IncA or OVA as described above. To determine if protective antibodies were produced from a previous infection, some mice were intranasally infected with 103 IFUs on day 0. On day 33, mice were depleted of CD4+ T cells by intraperitoneal injection of 0.2 mg GK1.5 antibody. Mice were then continuously depleted every week with 0.1 mg of GK1.5 until killed. On day 35, male mice were urethrally challenged with 106 IFUs of C. muridarum via the glans penis.27,54 Mice were infected for a further 21 days, before they were killed on day 56. Testes were collected and homogenized in sucrose phosphate glutamate with a 220 V generator probe (OMNI International, Kennesaw, GA, USA) for 10 s, and stored at −80 °C until IFUs were determined by culture on McCoy cells. Testes of uninfected mice were also collected, homogenized and solubilized in RIPA buffer, and western blotted to determine endogenous IgA and IgG within the tissue using goat anti-mouse IgA-HRP (alpha heavy chain) (Southern Biotech) and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (gamma heavy chain) (Southern Biotech).

Seven days prior to vaginal inoculation, female WT and β2m−/− mice were subcutaneously injected with 2.5 mg of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Pfizer, West Ryde, NSW, Australia) to synchronize animals in diestrus and facilitate chlamydial infection.7 Mice were then infected with MOMP-IgG opsonized, or OVA-IgG-treated EBs (40 μg IgG/5 × 103 IFUs in 10 μl sucrose phosphate glutamate). Infection was monitored every 3 days by vaginal swabbing. On day 35, mice were killed, hydrosalpinx formation in the oviducts recorded, and tissues fixed in 100% ethanol and prepared for histochemistry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of experiments was performed using Graphpad Prism version 5. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed where indicated. All mouse work was performed using five animals per group which was predicted to give >80% statistical power for shedding data. Significance was determined as * =P<0.05, ** = P<0.01 and *** =P<0.001. Graphs with error bars represent the mean±the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the infectious disease program at the Institute of Health and Biomedical Research and staff at the Herston Medical Research Centre. We thank Petra Sipila for the generous supply of mECap18 cells, Graham Le Gros for supply of cell lines and Mark Smyth for breeding pairs of β2m−/− mice. This project was supported by a grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (553055). CWA is supported by a QUT post-graduate research scholarship. RSB is funded by NIH grants DK044319, DK051362, DK053056, DK088199 and the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center (HDDC) (DK0034854). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The Supplementary Information that accompanies this paper is available on the Immunology and Cell Biology website (http://www.nature.com/icb)

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.WHO. Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections - 2008. In Research, RHa. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamm WE. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: progress and problems. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 2):S380–S383. doi: 10.1086/513844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Land JA, Van Bergen JE, Morre SA, Postma MJ. Epidemiology of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women and the cost-effectiveness of screening. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:189–204. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham KA, Beagley KW. Male genital tract chlamydial infection: implications for pathology and infertility. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:180–189. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunham RC, Rey-Ladino J. Immunology of Chlamydia Infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis Vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:149–161. doi: 10.1038/nri1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yule TD, Tung KS. Experimental autoimmune orchitis induced by testis and sperm antigen-specific T cell clones: an important pathogenic cytokine is tumor necrosis factor. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1098–1107. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.3.8103448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey AJ, Cunningham KA, Hafner LM, Timms P, Beagley KW. Effects of inoculating dose on the kinetics of Chlamydia muridarum genital infection in female mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:337–343. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Meara CP, Andrew DW, Beagley KW. The mouse model of Chlamydia genital tract infection: a review of infection, disease, immunity and vaccine development. Curr Mol Med. 2013;8:8. doi: 10.2174/15665240113136660078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Z, Chen C, Chen D, Wu Y, Zhong Y, Zhong G. Characterization of fifty putative inclusion membrane proteins encoded in the Chlamydia trachomatis genome. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2746–2757. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00010-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DM, Schachter J, Weiner MH, Grubbs B. Antibody in host defense against mouse pneumonitis agent (murine Chlamydia trachomatis) Infect Immun. 1984;45:674–678. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.3.674-678.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison SG, Morrison RP. A predominant role for antibody in acquired immunity to chlamydial genital tract reinfection. J Immunol. 2005;175:7536–7542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore T, Ananaba GA, Bolier J, Bowers S, Belay T, Eko FO, et al. Fc receptor regulation of protective immunity against Chlamydia trachomatis. Immunology. 2002;105:213–221. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scidmore MA, Rockey DD, Fischer ER, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. Vesicular interactions of the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion are determined by chlamydial early protein synthesis rather than route of entry. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5366–5372. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5366-5372.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su H, Spangrude GJ, Caldwell HD. Expression of Fc gamma RIII on HeLa 229 cells: possible effect on in vitro neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3811–3814. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3811-3814.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claypool SM, Dickinson BL, Yoshida M, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Functional reconstitution of human FcRn in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells requires co-expressed human beta 2-microglobulin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28038–28050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202367200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Bronson CL, Wani MA, Oberyszyn TM, Mohanty S, Chaudhury C, et al. Beta 2-microglobulin deficient mice catabolize IgG more rapidly than FcRn-alpha-chain deficient mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:603–609. doi: 10.3181/0710-RM-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knee RA, Hickey DK, Beagley KW, Jones RC. Transport of IgG across the blood-luminal barrier of the male reproductive tract of the rat and the effect of estradiol administration on reabsorption of fluid and IgG by the epididymal ducts. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:688–694. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.041079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Palaniyandi S, Zeng R, Tuo W, Roopenian DC, Zhu X. From the Cover: transfer of IgG in the female genital tract by MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) confers protective immunity to vaginal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4388–4393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012861108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida M, Claypool SM, Wagner JS, Mizoguchi E, Mizoguchi A, Roopenian DC, et al. Human neonatal Fc receptor mediates transport of IgG into luminal secretions for delivery of antigens to mucosal dendritic cells. Immunity. 2004;20:769–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai Y, Ye L, Tesar DB, Song H, Zhao D, Bjorkman PJ, et al. Intracellular neutralization of viral infection in polarized epithelial cells by neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated IgG transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18406–18411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115348108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine N, Kelly H. Measurement of pH in the rat epididymis in vivo. J Reprod Fertil. 1978;52:333–335. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0520333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy KM, Yoong Y, Simister NE. Bidirectional transcytosis of IgG by the rat neonatal Fc receptor expressed in a rat kidney cell line: a system to study protein transport across epithelia. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 7):1277–1285. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chi EY, Kuo CC, Grayston JT. Unique ultrastructure in the elementary body of Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3757–3763. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3757-3763.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackstadt T, Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Fischer ER. The Chlamydia trachomatis IncA protein is required for homotypic vesicle fusion. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1:119–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Finnie JM, Bao S, Coon C, Jones R, et al. Poly-immunoglobulin receptor-mediated transport of IgA into the male genital tract is important for clearance of Chlamydia muridarum infection. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junghans RP, Anderson CL. The protection receptor for IgG catabolism is the beta2-microglobulin-containing neonatal intestinal transport receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5512–5516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu C, Zeng H, Li Z, Lei L, Yeh IT, Wu Y, et al. Protective immunity against mouse upper genital tract pathology correlates with high IFNgamma but low IL-17T cell and anti-secretion protein antibody responses induced by replicating chlamydial organisms in the airway. Vaccine. 2012;30:475–485. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu X, Meng G, Dickinson BL, Li X, Mizoguchi E, Miao L, et al. MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG is functionally expressed in monocytes, intestinal macrophages, and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:3266–3276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ober RJ, Radu CG, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Differences in promiscuity for antibody-FcRn interactions across species: implications for therapeutic antibodies. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1551–1559. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gastinel LN, Simister NE, Bjorkman PJ. Expression and crystallization of a soluble and functional form of an Fc receptor related to class I histocompatibility molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:638–642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vidarsson G, Stemerding AM, Stapleton NM, Spliethoff SE, Janssen H, Rebers FE, et al. FcRn: an IgG receptor on phagocytes with a novel role in phagocytosis. Blood. 2006;108:3573–3579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker K, Qiao SW, Kuo TT, Aveson VG, Platzer B, Andersen JT, et al. Neonatal Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) regulates cross-presentation of IgG immune complexes by CD8-CD11b + dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9927–9932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019037108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manam S, Nicholson BJ, Murthy AK. OT-1 mice display minimal upper genital tract pathology following primary intravaginal Chlamydia muridarum infection. Pathog Dis. 2013;67:221–224. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Timms P, Beagley KW. CD4 + T cells reduce the tissue burden of Chlamydia muridarum in male BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2010;28:4861–4863. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Hafner L, Timms P, Beagley KW. Chlamydia muridarum major outer membrane protein-specific antibodies inhibit in vitro infection but enhance pathology in vivo. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;4:118–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cochrane M, Armitage CW, O’Meara CP, Beagley KW. Towards a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine: how close are we? Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1833–1856. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pate MS, Hedges SR, Sibley DA, Russell MW, Hook EW, 3rd, Mestecky J. Urethral cytokine and immune responses in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected males. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7178–7181. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.7178-7181.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng H, Gong S, Hou S, Zou Q, Zhong G. Identification of antigen-specific antibody responses associated with upper genital tract pathology in mice infected with Chlamydia muridarum. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1098–1106. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05894-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rzomp KA, Scholtes LD, Briggs BJ, Whittaker GR, Scidmore MA. Rab GTPases are recruited to chlamydial inclusions in both a species-dependent and species-independent manner. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5855–5870. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5855-5870.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fields KA, Hackstadt T. The chlamydial inclusion: escape from the endocytic pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:221–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holtta-Vuori M, Tanhuanpaa K, Mobius W, Somerharju P, Ikonen E. Modulation of cellular cholesterol transport and homeostasis by Rab11. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3107–3122. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rzomp KA, Moorhead AR, Scidmore MA. The GTPase Rab4 interacts with Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT229. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5362–5373. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00539-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward ES, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Tang Q, Ober RJ. From sorting endosomes to exocytosis: association of Rab4 and Rab11 GTPases with the Fc receptor, FcRn, during recycling. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2028–2038. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaw EI, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Scidmore MA, Fields KA, Hackstadt T. Three temporal classes of gene expression during the Chlamydia trachomatis developmental cycle. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:913–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sipila P, Shariatmadari R, Huhtaniemi IT, Poutanen M. Immortalization of epididymal epithelium in transgenic mice expressing simian virus 40T antigen: characterization of cell lines and regulation of the polyoma enhancer activator 3. Endocrinology. 2004;145:437–446. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Madi A, Svinareff P, Orange N, Feuilloley MG, Connil N. Pseudomonas fluorescens alters epithelial permeability and translocates across Caco-2/TC7 intestinal cells. Gut Pathog. 2010;2:2–16. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Claypool SM, Dickinson BL, Wagner JS, Johansen FE, Venu N, Borawski JA, et al. Bidirectional transepithelial IgG transport by a strongly polarized basolateral membrane Fcgamma-receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1746–1759. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Lycke N, Timms P, Beagley KW. CTA1-DD is an effective adjuvant for targeting anti-chlamydial immunity to the murine genital mucosa. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;81:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T. Identification and characterization of a Chlamydia trachomatis early operon encoding four novel inclusion membrane proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:753–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carabeo RA, Grieshaber SS, Fischer E, Hackstadt T. Chlamydia trachomatis induces remodelling of the actin cytoskeleton during attachment and entry into HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3793–3803. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3793-3803.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Meara CP, Armitage CW, Harvie MC, Timms P, Lycke NY, Beagley KW. Immunization with a MOMP-based vaccine protects mice against a pulmonary Chlamydia challenge and identifies a disconnection between infection and pathology. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. New murine model for the study of chlamydia trachomatis genitourinary tract infections in males. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4210–4216. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4210-4216.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.